1. Introduction

Based on advanced sensing networks embedded on the structure surface, aircraft structural health monitoring technology can first acquire the monitoring signal regarding the structural healthy state. Then, the signal features representing the structural healthy state are extracted with load analysis methods and signal processing methods. This technology shows enormous application potential in improving structural safety, reducing maintenance costs, performing the predictive maintenance strategy and prolonging the service time [

1,

2]. According to the diversity of sensing networks, the structural health monitoring (SHM) technology can be divided into piezoelectricity transducer (PZT) [

3,

4], fiber Bragg gating (FBG) [

5], acoustic emission transducer (AE) [

6] and comparative vacuum monitoring (CVM) [

7], et al. [

8,

9]. With the merits of long propagation distance, low signal attenuation and high sensitivity to the small damage of Lamb waves (LWs) actuated by PZT, the damage monitoring technology using LWs has been regarded as an effective and appealing damage monitoring technology.

According to the structural damage monitoring capability using LWs, the damage monitoring technology can be classified as damage identification, damage location [

10] and damage quantitative [

11], among which damage identification is the most basic and essential research domain. Many damage identification methods have been developed. Liu et al. [

12] proposed a damage identification method based on the energy ratio damage index (

EDI) using LWs and Hilbert transform and validated on the damage evolution experiment of composite lap joint specimens. The results show that the threshold of

EDI is capable of identifying the disbonding damages of composite lap joint specimens. Shahab et al. [

13] extracted twelve signal features from time and frequency domains perspectives and compared the debonding damage detection capacity of different features. Wu et al. [

14] extracted the energy ratio features of time, frequency and time–frequency domains and compared the damage detection capacities using damage imaging methods. Su et al. [

15] developed a Lamb wave-based quantitative identification method of delamination damage using an artificial neural network (ANN), in which Digital Damage Fingerprints (

DDFs) extracted from the LWs in the time–frequency domain were used as the input for a multi-layer feed-forward ANN under the supervised training of an error back-propagation (BP) algorithm. Torkamani et al. [

13] introduced an innovative time-domain damage index called the normalized correlation moment (

NCM) based on local statistical features of the wave form, which shows a superior capacity on the delamination damage detection and damage assessment compared with

SDCC. Yan et al. [

16] extracted the local time–energy density feature with the Gabor wavelet basic function and took the difference coefficient between the features as the damage index, which detected the simulated damage of composite stiffened panels. Loendersloot et al. [

17] introduced fifteen signal features and developed a graphical user interface to visually assess the damage detection performance of different signal features, considering the different damage identification capacities for different signal features. Damage identification using LWs is generally realized by establishing the mapping relationship between the single signal feature and the structural healthy state based on the signal feature threshold or the state equation. However, different signal features present different sensitivity to the damage, unequal damage identification capability and inconsistent damage identification accuracy.

Recently, with the rapid development of multi-source information fusion (MSIF) [

18], it has been widely used in the structural damage monitoring field. Christoph et al. [

18] reviewed SHM methods based on multi-sensor data fusion for the damage assessment of metal and composite structures and discussed data-level fusion methods, feature-level fusion methods and decision-level fusion methods. He et al. [

19] developed a damage identification method for the unmanned aerial vehicle structure, by fusing the strain data, the acceleration data and the modal frequency data with data-level fusion, feature-level fusion and decision-level fusion. Qiu et al. [

20] proposed a crack propagation monitoring method based on a guided wave–Gaussian mixture model (GW-GMM) by using LW-based feature extraction to obtain multi-dimensional damage indexes in time and frequency domains and adopted principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensions and extract the prominent signal features, in which PCA is a feature-level fusion method. Ziemowit et al. [

21] developed a damage detection method with some damage indexes as inputs of ANN, which works as a feature-level fusion method. Jiang et al. [

22] proposed a multi-sensor data fusion fault diagnosis method based on support vector machine (SVM) and evidence theory, in which one-versus-one multi-class SVM is used to obtain the basic probability assignment (BPA), and the matrix analysis is presented to solve the calculation bottle-neck problem of evidence theory in decision-level fusion. Liewellyn et al. [

23] proposed a reliable impact detection strategy for composite structures. In this method, ANN is firstly used as a pattern recognition and classification method with the input of a combination of instantaneous frequencies, continuous wavelet transform (CWT) coefficient integrals, power spectral density (PSD) integrals and Bayesian updating (BU). Then, the Kalman filter (KF) is adopted as a decision-level fusion method to fuse these damage detection results on sub-networks considering the fault sensors network. Yang et al. [

24] developed an integrated damage identification method based on the least margin for composite structures. In this method, the identification results of some machine learning models are integrated with the most confidence, which is a decision-level fusion method. However, the research on an LW-based damage identification method with MSIF has not yet been widely studied. And the current damage fusion identification methods based on LW have not considered the strong correlation between the multi-dimensional signal features that have been input, and information redundancy may exist.

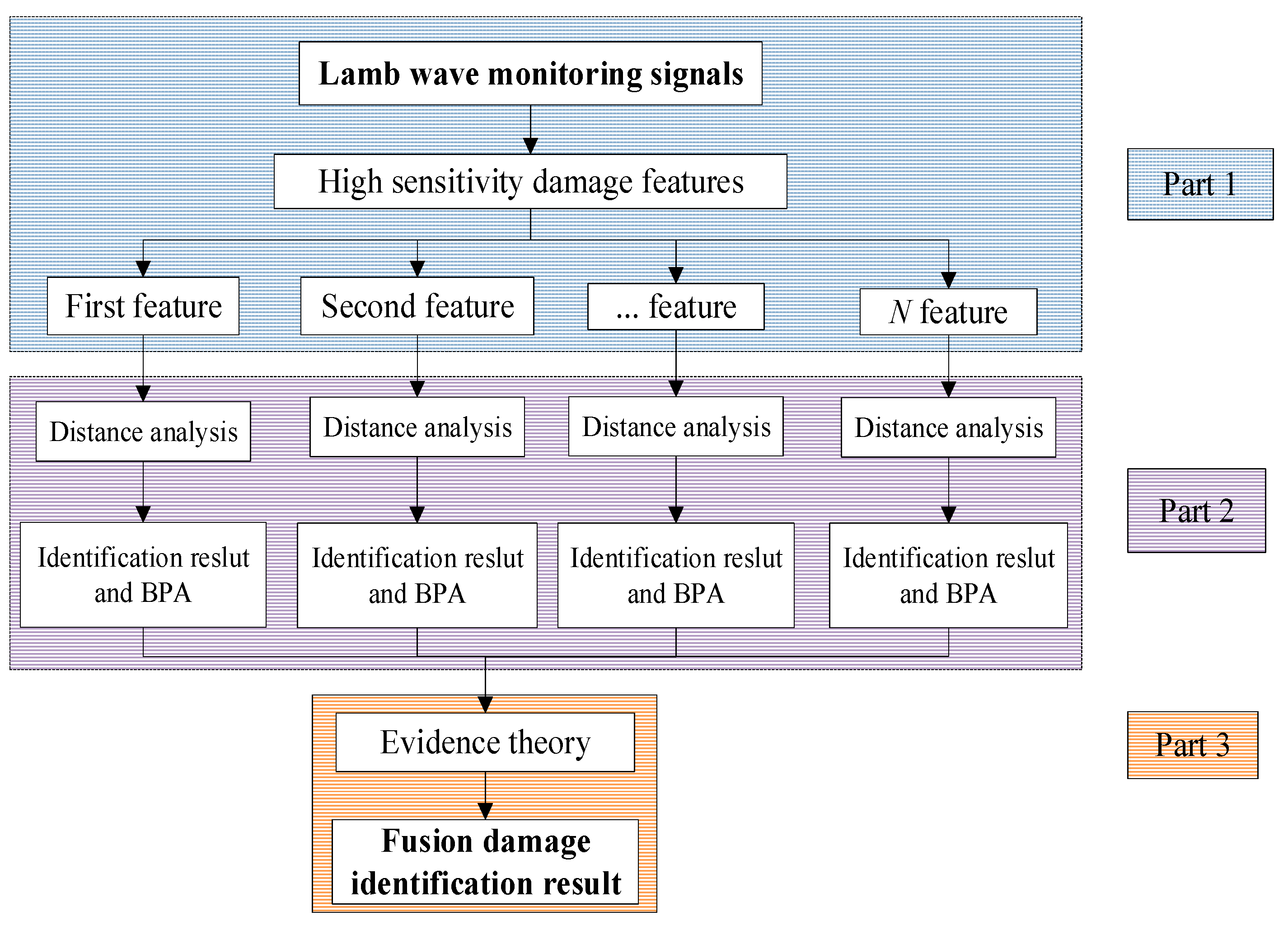

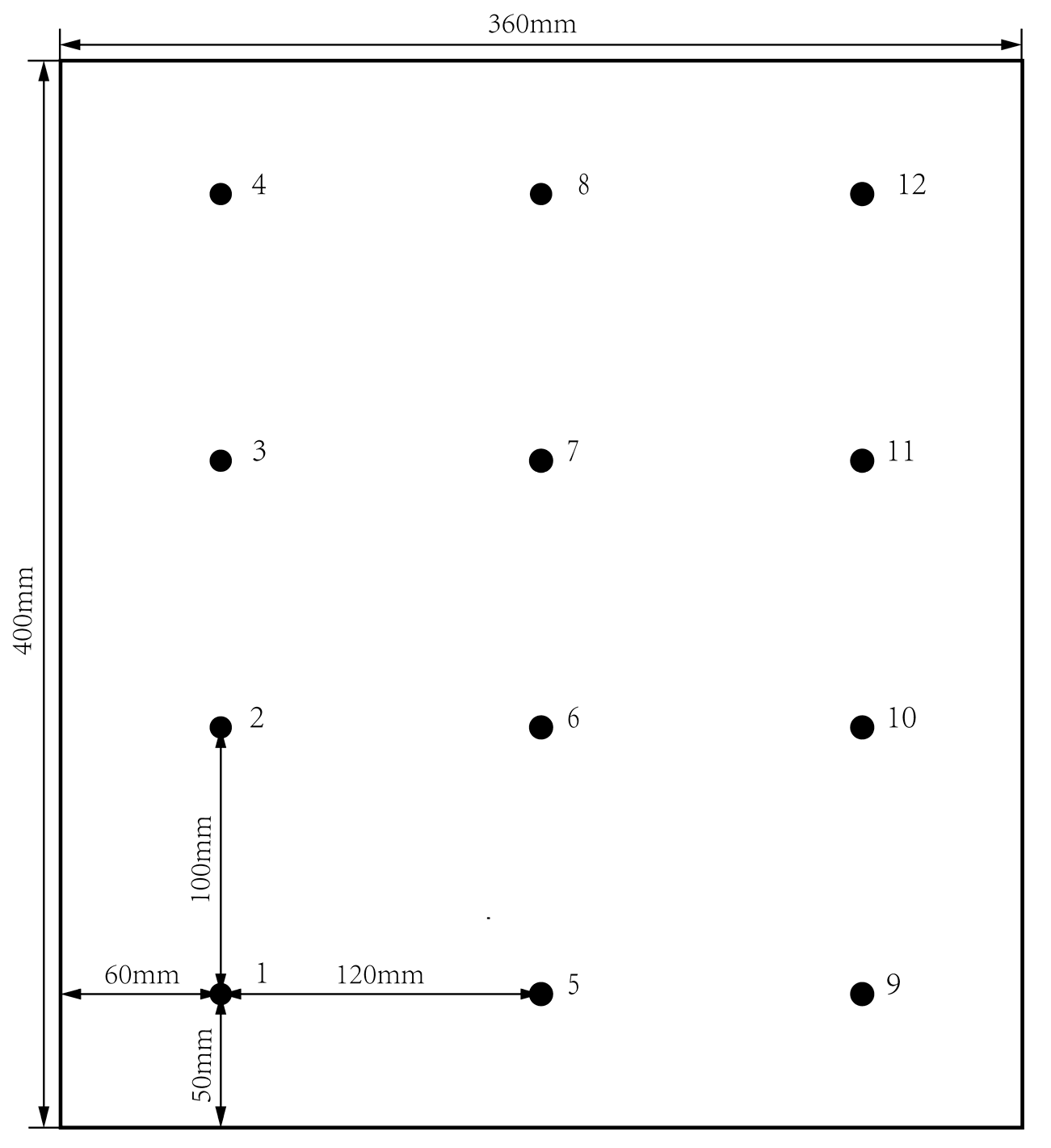

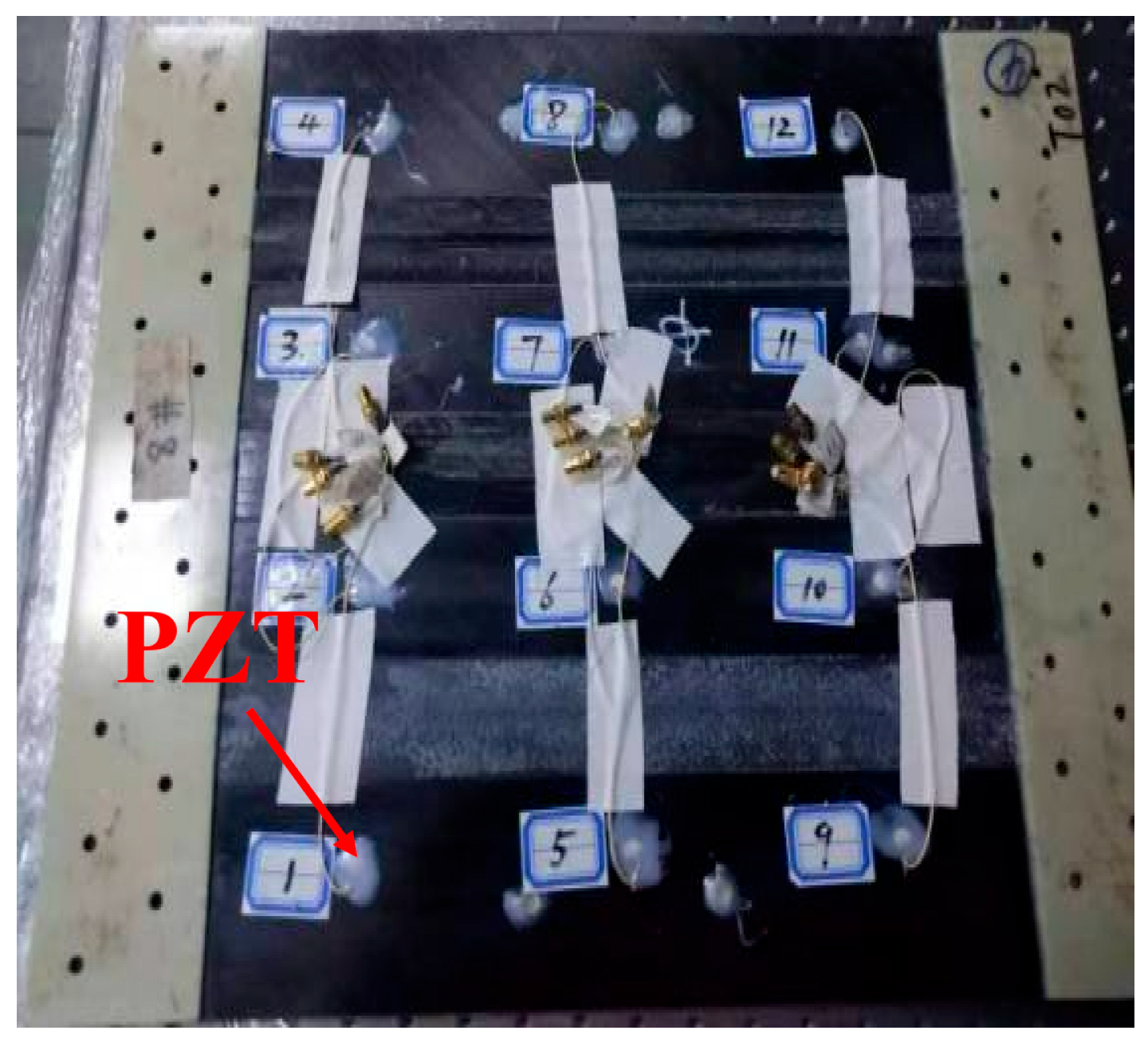

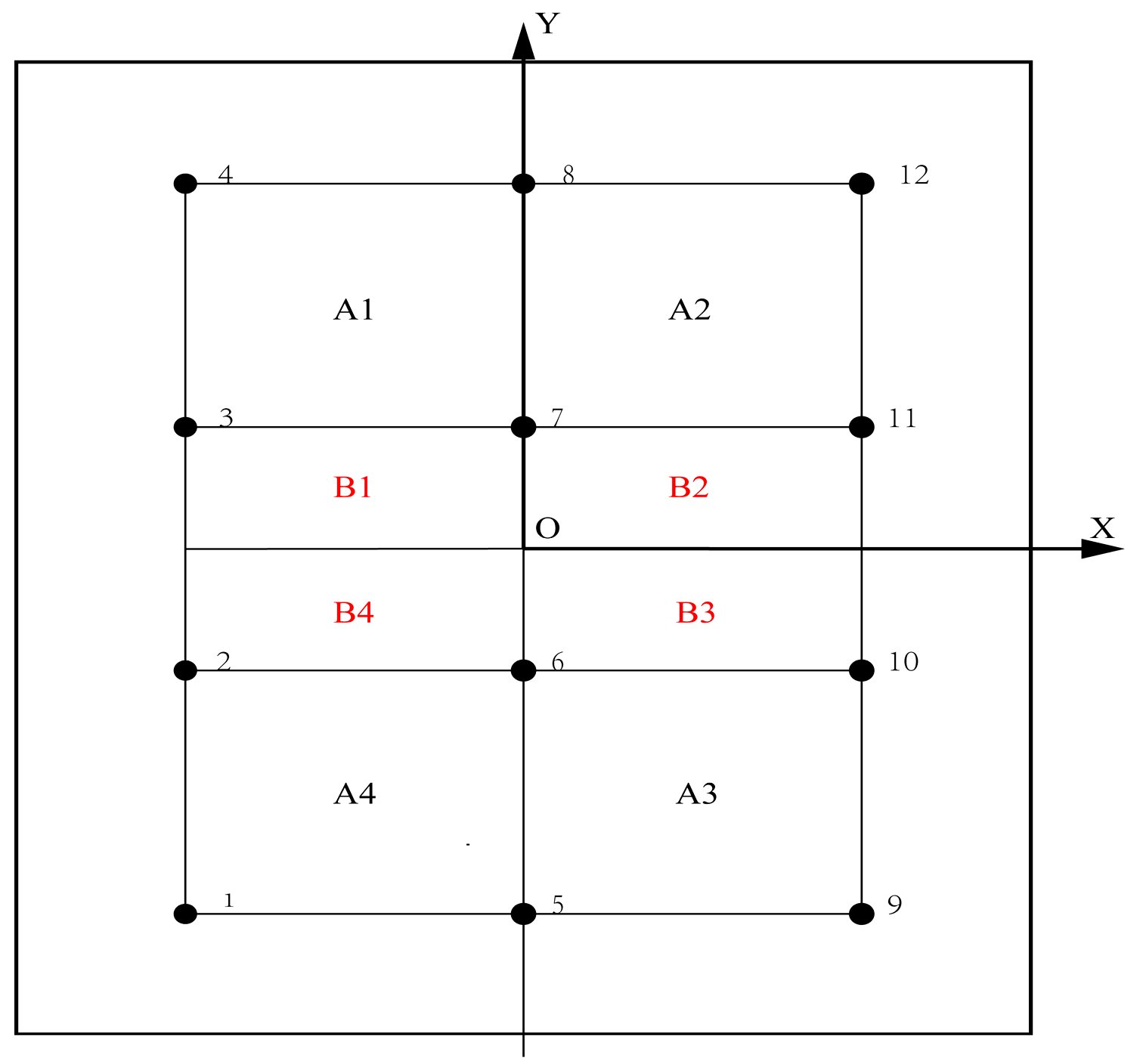

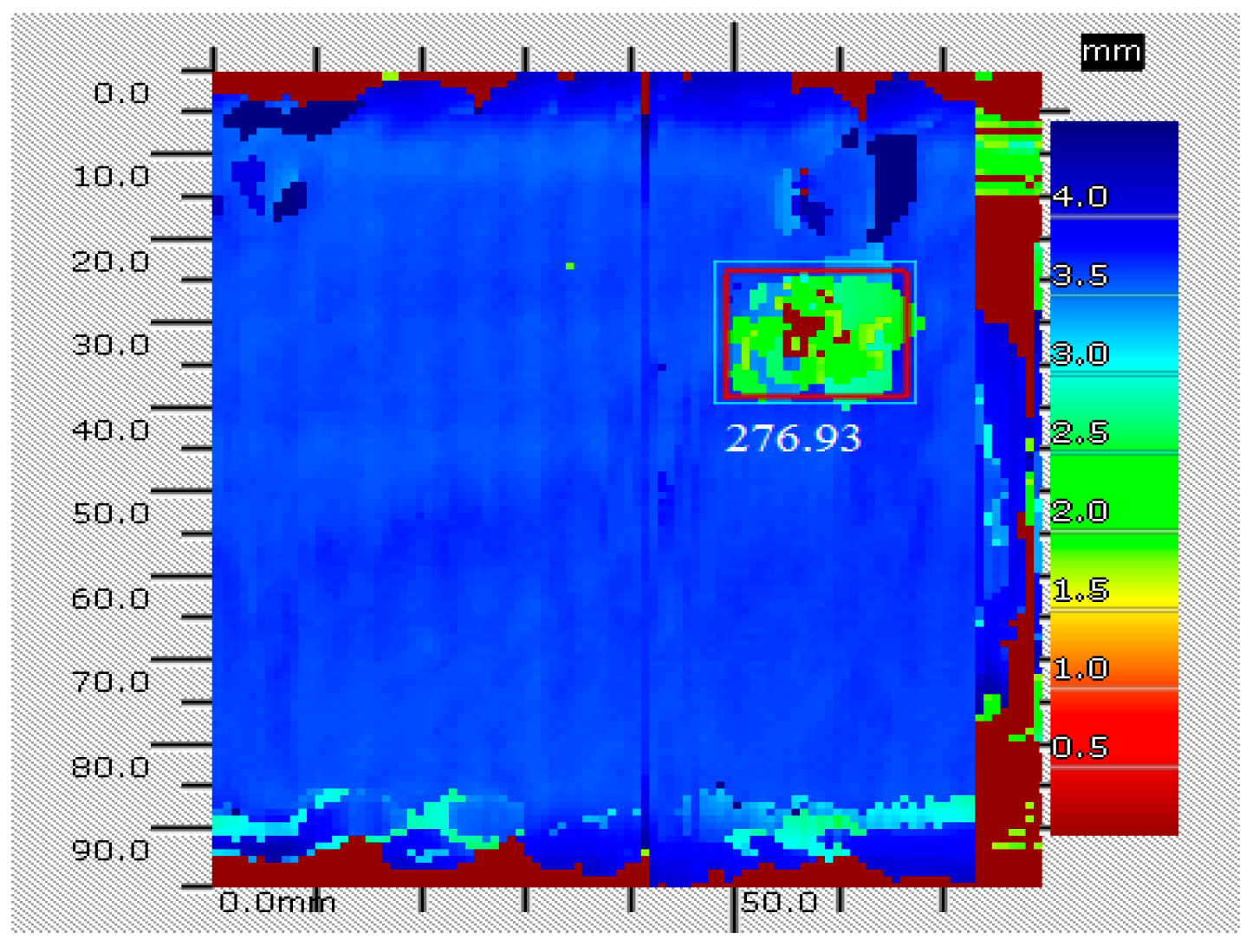

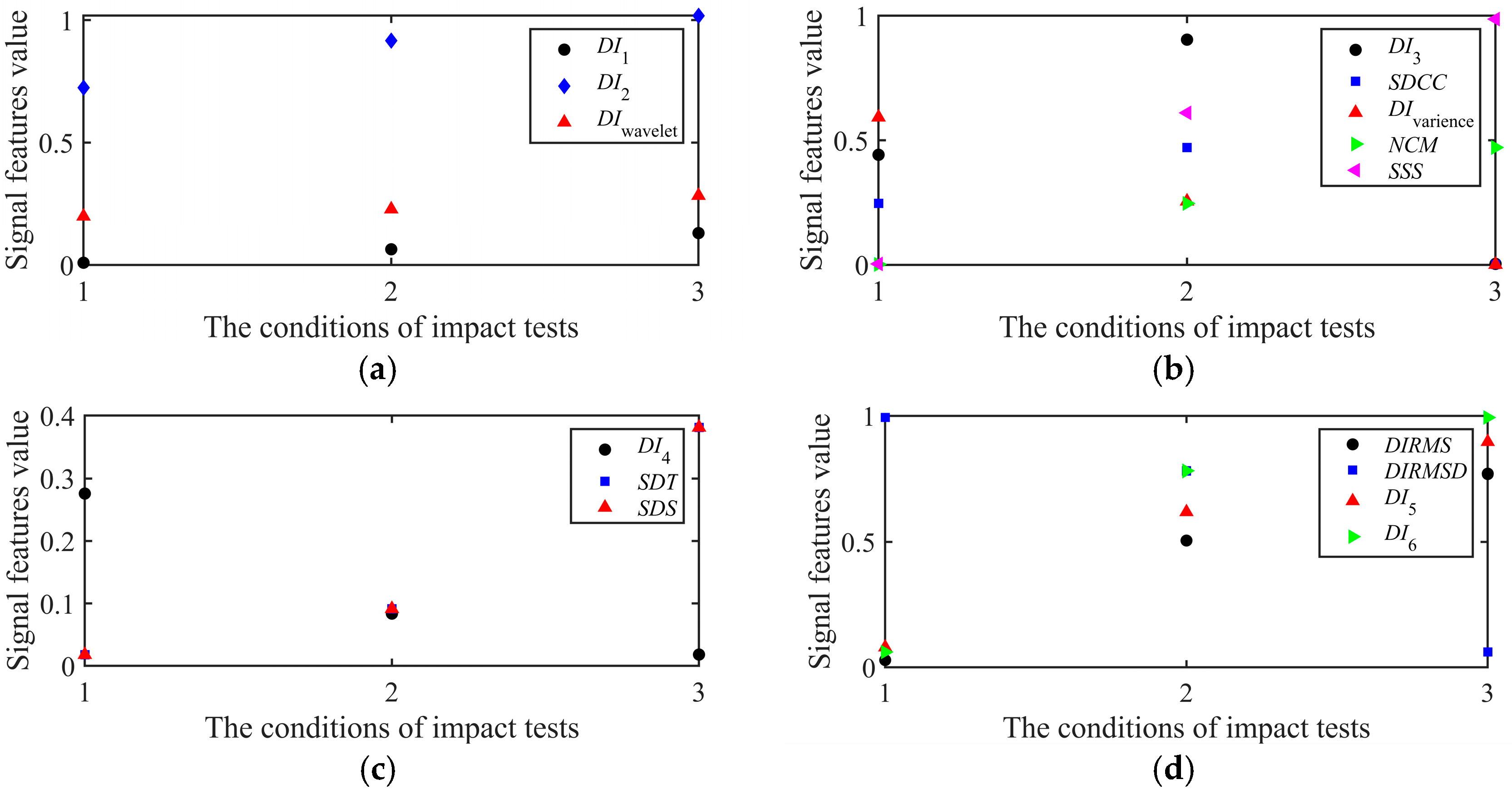

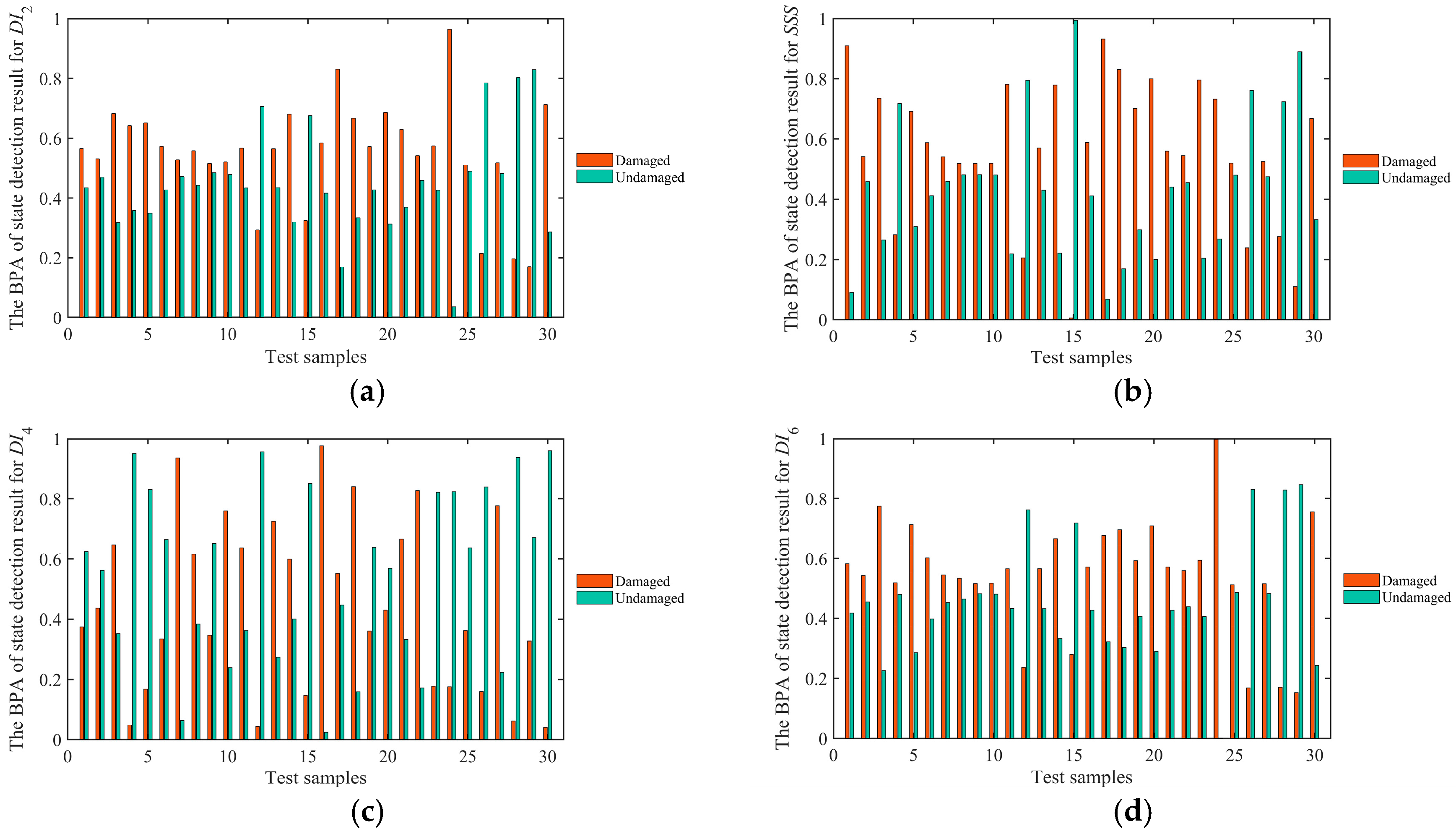

Considering the aforementioned challenges existing in both the conventional damage detection methods based on signal features and the current damage fusion detection methods based on multi-level fusion strategy, a damage fusion identification method based on distance analysis and evidence theory is developed in this paper, to obtain the consistent damage identification result for the delamination damage. Firstly, the common 15-dimensional signal features of LWs are extracted from the time, frequency and time–frequency domains. Secondly, the four orthogonal and highly sensitive signal features are retained based on Pearson correlation coefficient and cluster analysis. Thirdly, the data are divided into the training dataset and the testing dataset, whose labels are determined according to the delamination area. Fourthly, the damage identification results and the corresponding basic probability assignments (BPAs) of each highly sensitive signal feature for each testing sample are obtained based on distance analysis. Lastly, the consistent damage identification result is acquired by fusing the BPAs of four sensitive signal features based on Dempster fusion criterion of evidence theory. The accuracy and reliability of the proposed method are validated on damage monitoring experiments of ten composite laminate panels.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the proposed damage identification method based on distance analysis in detail, including Lamb wave-based multi-dimensional signal features extraction; feature dimension reduction based on Pearson correlation coefficient and cluster analysis; a damage identification-based distance analysis algorithm; a damage identification process based on highly sensitive features and a distance analysis algorithm.

Section 3 presents the proposed damage fusion identification method based on distance analysis and evidence theory in detail, including a brief review of evidence theory, BPAs based on Euclidean distance and the whole fused damage identification process. In

Section 4, validation experiments on ten composite laminate panels are performed to evaluate the damage identification accuracy and reliability of the proposed method. Conclusions are given in

Section 5.

2. Distance Analysis

2.1. Lamb Wave-Based Signal Features Extraction

In order to directly express the effect of structural damage on LW signals, many typical signal features based on LWs are extracted. Multi-dimensional signal features can be extracted from LWs in the time domain, the frequency domain and the time–frequency domain [

17]. In this paper, the common 15- dimensional signal features are extracted, as shown in

Table 1.

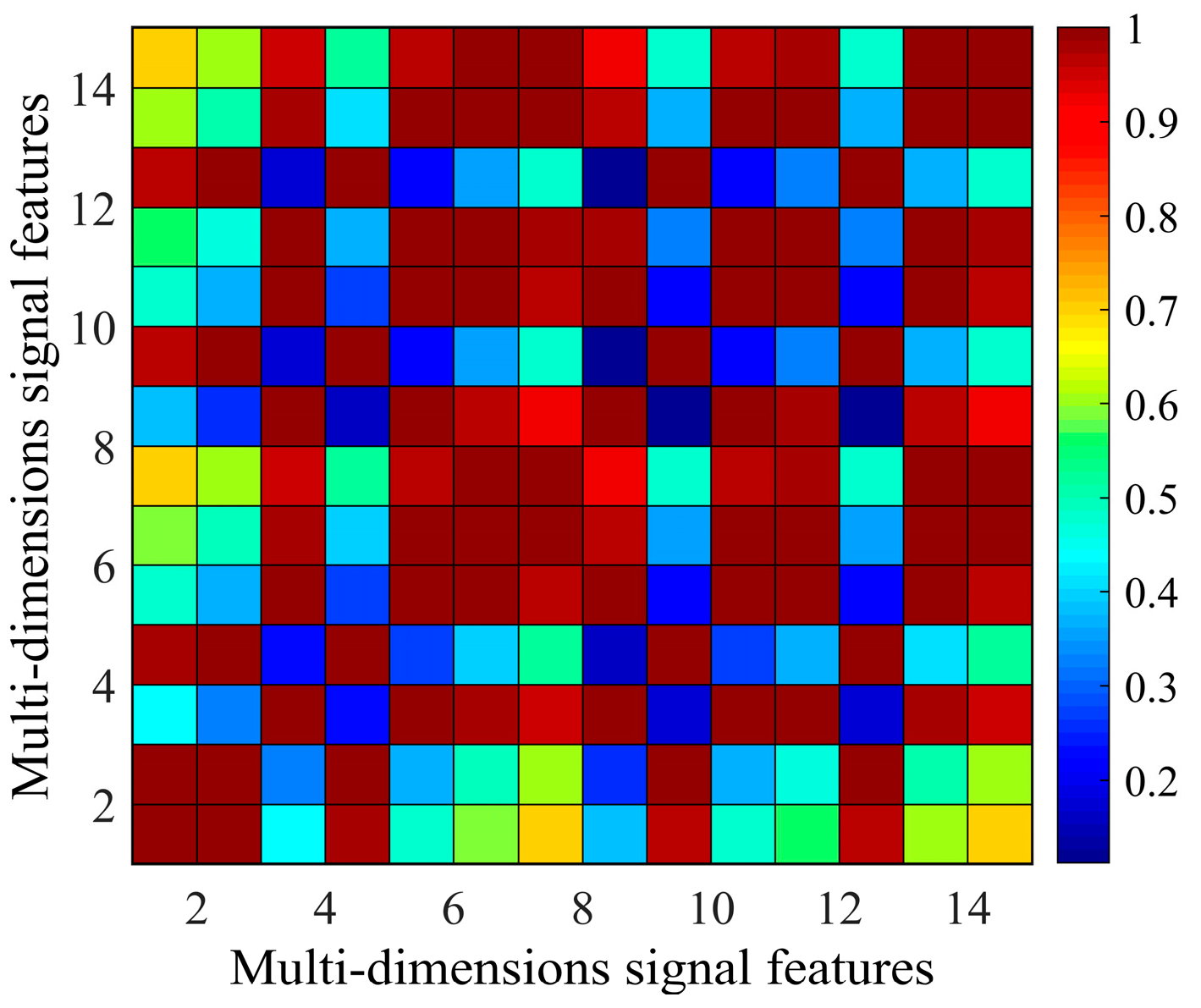

2.2. Feature Dimensions Reduction Based on Pearson Correlation Coefficient and Cluster Analysis

Considering the extremely strong correlation between several features, it is crucial to analyze the correlation of 15-dimensional signal features. Many correlation analysis methods are applied based on the Pearson correlation matrix, the covariance matrix and the multivariate regression model, etc., [

25,

26,

27]. The Pearson correlation matrix is used to reduce the dimensions of fifteen signal features to retain the orthogonal and highly sensitive signal features in this paper.

Assuming that the

X is multi-dimensional signal features vector shown in Equation (1), in which

κ is the number of experimental situations, and

a is the number of feature dimensions, setting to

a = 15 in this paper.

The Pearson correlation matrix

P is defined as follows:

where

ρra is the Pearson correlation coefficient between the signal features vector

Xr and the signal features vector

Xa, and is expressed as follows:

where

is the average of the signal features vector

Xr, and X

ro is the signal feature under different experimental situations.

is the average of signal features vector

Xa, and X

ao is the signal feature under different experimental situations.

The sensitivity

Z is adopted to evaluate the sensitivity of different signal features with the change in structural health states [

28]. The sensitivity of the signal features vector

Xr can be expressed as Z

r and can be written as follows:

where

and

are the signal features vector under the undamaged and damaged states.

and

are the standard deviation of the signal features vector under the undamaged and damaged states.

p1 and

p2 are the corresponding number of undamaged and damaged samples.

A cluster analysis algorithm is used to further subtract the feature dimensions. The procedure of the cluster analysis algorithm is as below.

(1) Set the first signal features vector X1 as the initial cluster set Cr (r = 1);

(2) Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient ρmn between each signal feature Xm in the initial signal feature vector set Cr (Xm∈Cr) and the other signal features vector Xn (n = 1, 2, 3…15 and n ≠ m);

(3) Compare the Pearson correlation coefficient ρmn with the threshold δ. If the Pearson correlation coefficient ρmn exceeds δ, then add the signal features vector Xn into the cluster Cr (Cr = Cr∪Xn). Otherwise, choose the random signal features vector which is not in the cluster Cr as the next new initial cluster Cr(r←r + 1), and then skip to step (2);

(4) After the 15-dimensional signal features are all added into clusters, count Z of every signal feature in each ultimate cluster under different structural health states;

(5) Select the signal feature with the maximum Z in each cluster and then obtain the highly sensitive signal features set.

2.3. Damage Identification Based Distance Analysis

Distance analysis is a lazy supervised learning algorithm, which only saves the samples during the training process without training. After receiving the testing samples, the main training process is as below.

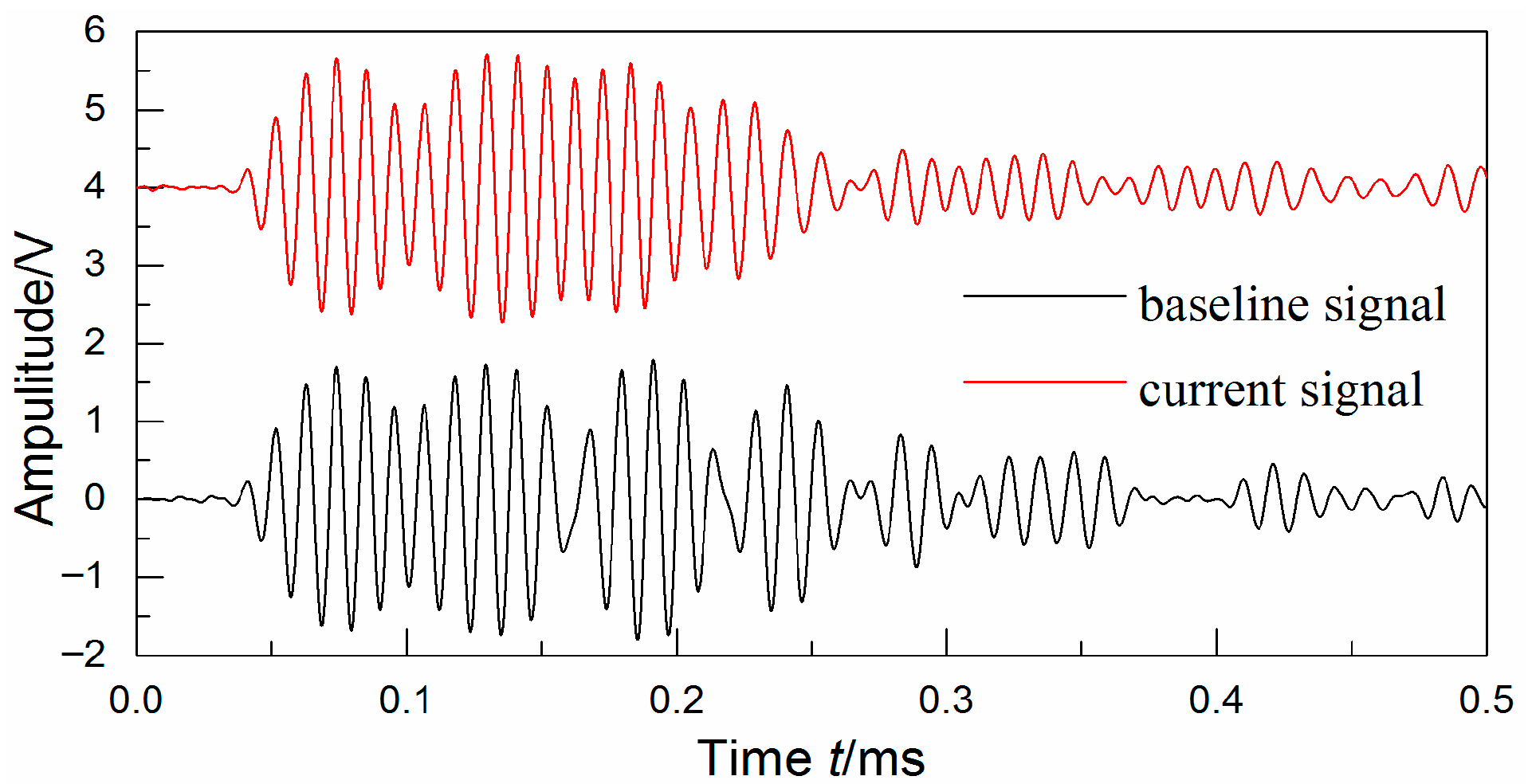

(1) For baseline signals and current signals under different structural health states, the 15-dimensional signal features are extracted and then the highly sensitive signal features are reduced to form the training dataset.

(2) According to the sample labels for each highly sensitive signal feature, the training dataset is allocated into diverse clusters, whose respective label is consistent with the sample labels. In this paper, the training sample label is either undamaged or damaged. Thus, the training dataset of every highly sensitive signal feature is divided into two clusters, one tagged with the undamaged label and the other tagged with the damaged label, defined, respectively, as the undamaged cluster and the damaged cluster.

(3) When the new monitoring signal is acquired, the highly sensitive signal features can be extracted and regarded as a testing sample. For each testing sample, its state label’s predicted result depends on the cluster label of each highly sensitive signal feature, in which the sum of the Euclidean distance between the training samples and the testing sample is the miner.

Assuming that the training dataset for the highly sensitive signal feature

Xn can be expressed as

N, the training dataset

N can be divided into the undamaged cluster and the damaged cluster, thus

N = {

N1,

N2}. The Euclidean distance

between the testing sample

q and the cluster

Np can be obtained as follows:

Then the state label’s predicted result λ(

q) of the testing sample

q can be given by the following:

where the function arg(.) means that the testing sample’s state label is consistent with the cluster.

2.4. Damage Identification Process Based on Highly Sensitive Features and Distance Analysis

The damage identification process based on highly sensitive signal features and distance analysis algorithm includes two procedures: the feature extraction and reduction and the damage identification.

Feature extraction and reduction procedure: Firstly, Lamb wave signals are obtained under different structural health states, including the baseline signals and the respective current signals. Then, 15-dimensional signal features are extracted in the time domain, the frequency domain and the time–frequency domain. Furthermore, the orthogonal signal features are reduced from 15-dimensional signal features based on the Pearson correlation coefficient and cluster analysis algorithm. Finally, the highly sensitive signal features are retained and assigned as the training dataset.

Damage identification procedure: Once a new monitoring experimental situation has occurred, the highly sensitive signal features can be extracted based on the baseline signals and the new current signals of all monitoring paths. Then, the orthogonal and highly sensitive signal features are assigned as the testing dataset. With the training dataset and testing dataset, the distance analysis algorithm is applied to identify the damage. Finally, the damage identification results of different highly sensitive signal features are obtained separately.

5. Conclusions

The damage fusion identification method based on distance analysis and evidence theory is proposed in this paper, and the method is used to fuse the respective damage identification results of four highly sensitive signal features in order to obtain the consistent identification results. In the proposed method, four highly sensitive signal features are firstly retained based on the Pearson correlation coefficient and cluster analysis, by reducing 15-dimensional signal features extracted from the time domain, the frequency domain and the time–frequency domain. Then, the respective damage identification results of four highly sensitive signal features are acquired based on distance analysis, and the BPAs of the identification results are obtained by computing the Euclidean distance. Finally, the damage fusion identification result is acquired by fusing the BPAs of the damage identification results for four highly sensitive signal features with the decision-level fusion method, based on evidence theory. The effectiveness of the proposed damage identification method was assessed by identifying impact damages under different locations with different areas on ten composite laminate panels. The results show that the damage fusion identification method can accurately identify the impact damage with high probability, and the classification accuracy of 76 testing samples is above 85%, the false alarm rate is lower than 25% and the missing alarm rate is lower than 15%. The proposed damage fusion identification method presents a superior accuracy and probability for the damage identification of composite laminate panels.

The proposed method is a damage identification method for composite laminate panels, which is only able to accurately detect the delamination damage with areas above 200 mm2, but unable to detect small damage cases or further evaluate damage. Therefore, in future research, the small damage detection ability needs to be investigated. Moreover, the small damage location and quantification monitoring methods also need further study.