Progressive Multi-Scale Perception Network for Non-Uniformly Blurred Underwater Image Restoration

Abstract

1. Introduction

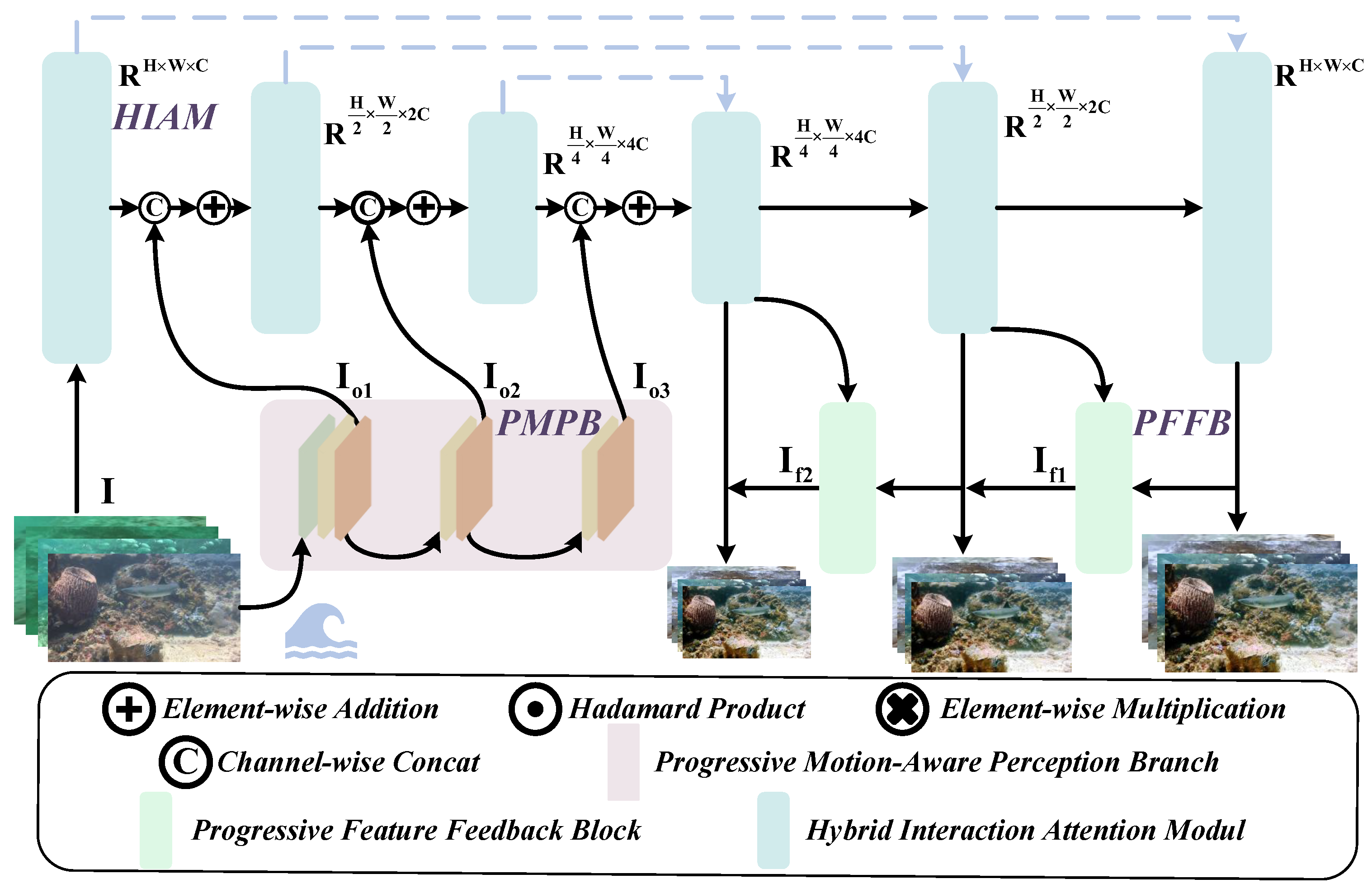

- We propose a Progressive Multi-Scale Perception Network to effectively eliminate non-uniform blur in underwater images, enabling real-time underwater image enhancement.

- We introduce a Hybrid Interaction Attention Module that extracts and integrates local and global blur features to capture multi-view information and accurately perceive the direction and intensity of underwater blur.

- We design a Progressive Motion-Aware Perception Branch and a Progressive Feature Feedback Block to enable progressive fine-tuning of features, precise localization of blur, and efficient recovery of reconstruction details.

- We construct a Non-uniform Underwater Blur Dataset to provide a benchmark for evaluating underwater image deblurring algorithms. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms state-of-the-art approaches, validating its robustness and effectiveness.

2. Related Work

2.1. Hardware-Based Approach

2.2. Traditional Approach

2.3. Data-Driven Approach

3. Methods

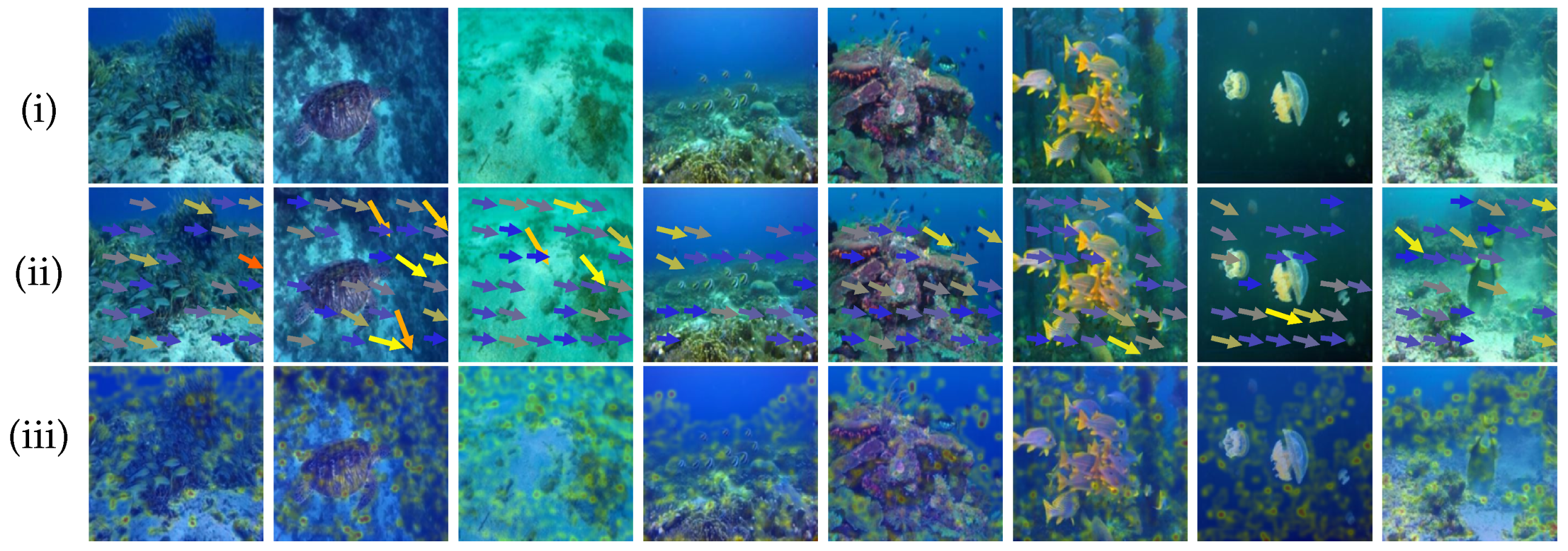

3.1. N2UD

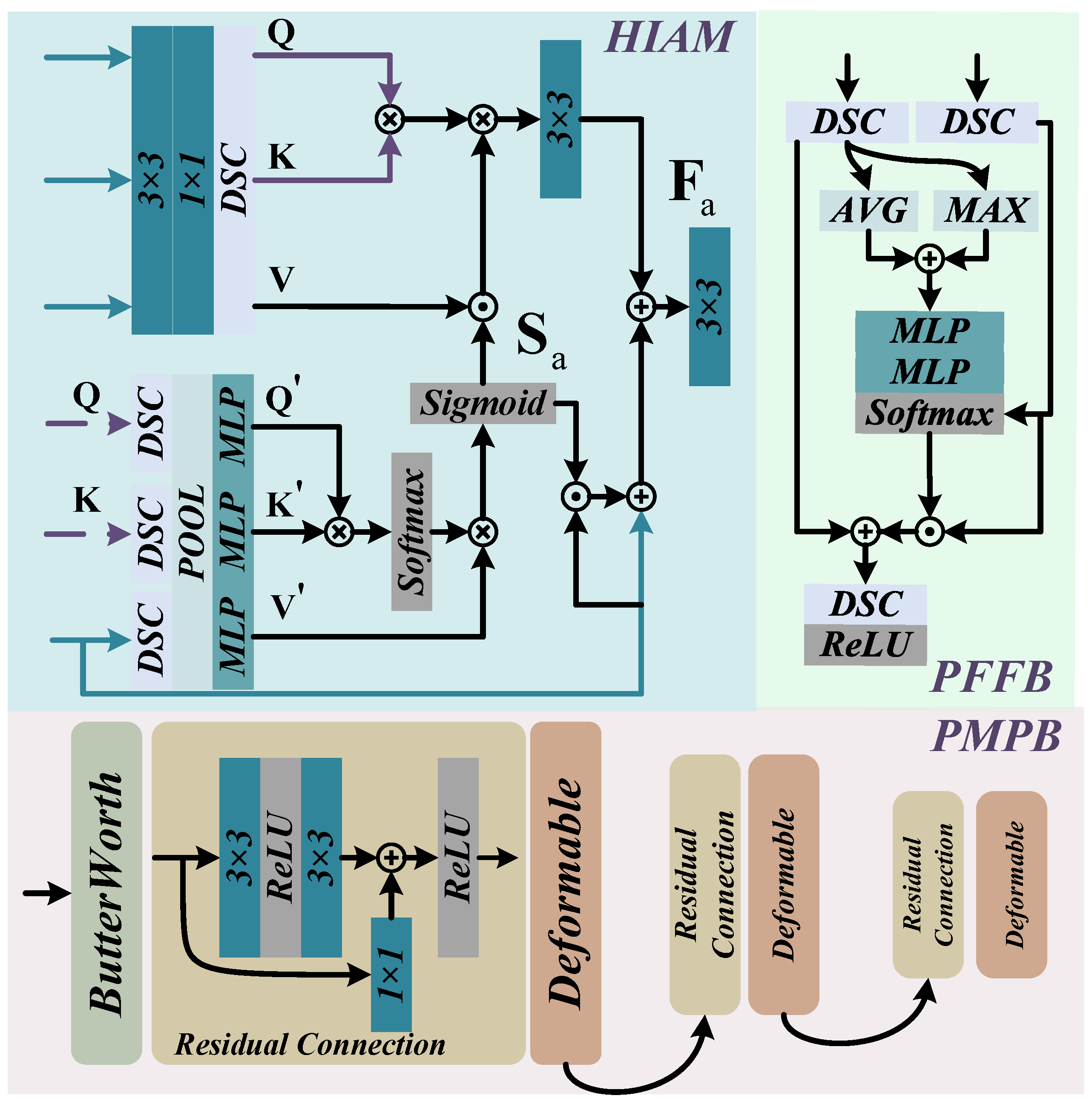

3.2. Hybrid Interaction Attention Module

3.3. Progressive Motion-Aware Perception Branch

3.4. Progressive Feature Feedback Block

3.5. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. N2UD

4.1.2. EUVP

4.1.3. LSUI

4.1.4. UIEB

4.1.5. DUO

4.2. Experimental Configuration

4.2.1. Implementation Details

4.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

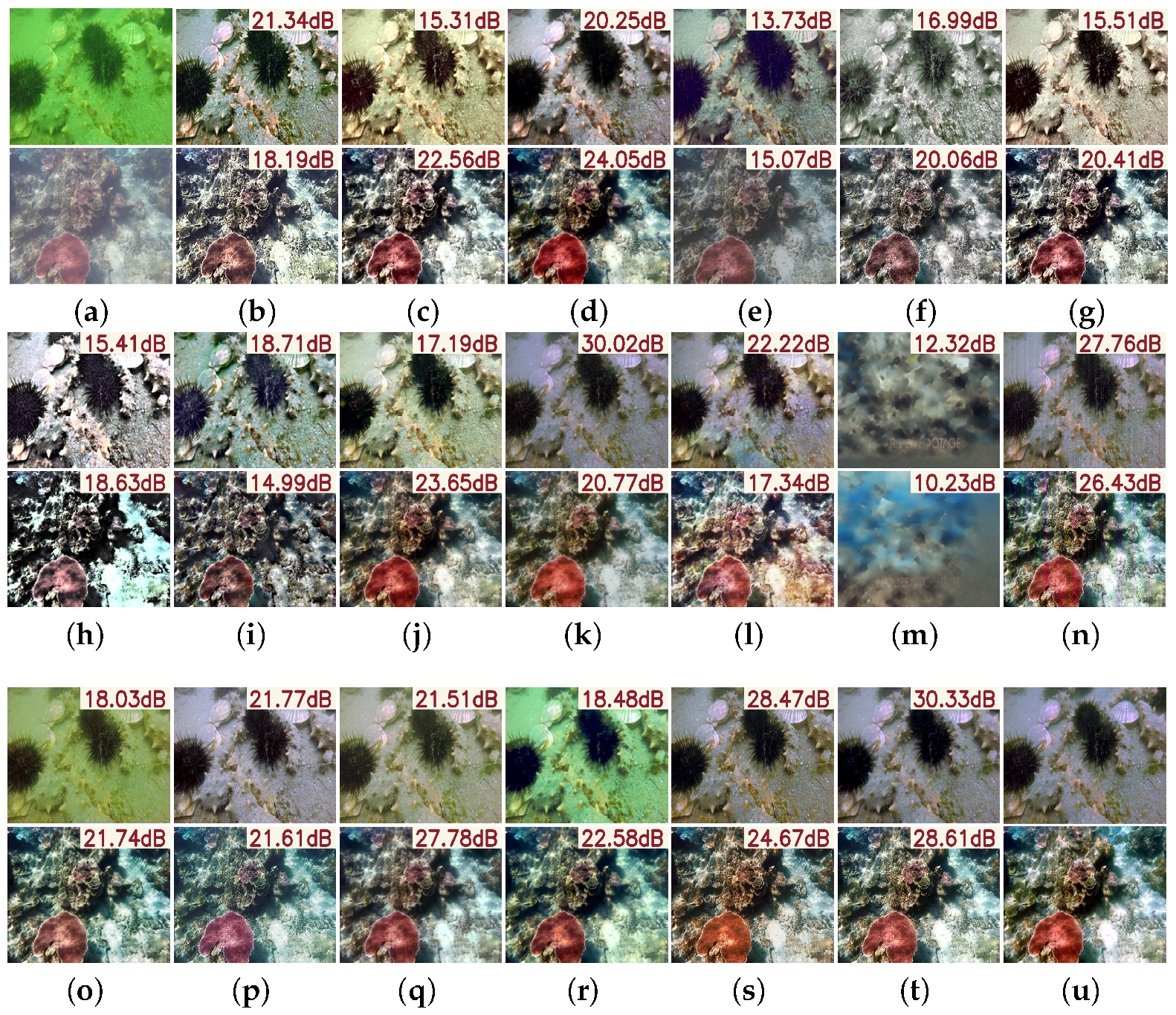

4.3. Performance Comparison

4.3.1. N2UD

4.3.2. EUVP

4.3.3. LSUI

4.3.4. UIEB

4.4. Ablation Study

4.4.1. Butterworth Filter

4.4.2. Deformable Convolution

4.4.3. Progressive Motion-Aware Perception Branch

4.4.4. Progressive Feature Feedback Block

4.4.5. Loss Function

4.4.6. Blur Perceptual Localization

4.4.7. Downstream Task Evaluation

4.4.8. Limitation Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Long, B.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Q.; Muhammad, G. Degradation-Decoupling Vision Enhancement for Intelligent Underwater Robot Vision Perception System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 17880–17895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Hui, X.; Ma, X.; Bai, X.; Tan, M. Underwater Robots and Key Technologies for Operation Control. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sabbagh, S.P.; Robles-Kelly, A. A Survey on Underwater Computer Vision. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Reda, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, S.G. Polarization-Driven Solution for Mitigating Scattering and Uneven Illumination in Underwater Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Fu, X. An Underwater Image Restoration Method With Polarization Imaging Optimization Model for Poor Visible Conditions. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 3924–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, M. Multi-modality object detection with sonar and underwater camera via object-shadow feature generation and saliency information. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 287, 128021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Zhai, Y.; Dong, L. A laser field synchronous scanning imaging system for underwater long-range detection. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, S. AQUA-SLAM: Tightly Coupled Underwater Acoustic-Visual-Inertial SLAM With Sensor Calibration. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 2785–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Han, G.; Hou, Y.; Lin, C. Environment-Tolerant Trust Opportunity Routing Based on Reinforcement Learning for Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 6348–6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Pan, M.; Xu, G.; Cui, J.H. Joint Power Control and Multipath Routing for Internet of Underwater Things in Varying Environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 15197–15210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Feng, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, H. Security and Reliability of InternSecurity and Reliability of Internet of Underwater Things: Architecture, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draz, U.; Ali, T.; Yasin, S.; Chaudary, M.H.; Yasin, I.; Ayaz, M.; Aggoune, E.H.M. Hybrid Underwater Localization Communication Framework for Blockchain-Enabled IoT Underwater Acoustic Sensor Network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 16858–16885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, C.; Varshitha, G.S.; Divya, D.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Srivastava, G. A Novel and Robust Authentication Protocol for Secure Underwater Communication Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Boukerche, A.; Yang, Q. An Efficient Secure and Adaptive Routing Protocol Based on GMM-HMM-LSTM for Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 16491–16504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, A.; Sreenivas, M.; Biswas, S. PhISH-Net: Physics Inspired System for High Resolution Underwater Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 1506–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, T.; Ren, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W. Underwater image restoration via depth map and illumination estimation based on a single image. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 29864–29886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Huang, J.; Shen, C.; Jiang, Z. Retinex-inspired underwater image enhancement with information entropy smoothing and non-uniform illumination priors. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 162, 111411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, H.; An, D.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Z. Turbid Underwater Image Enhancement with Illumination-Constrained and Structure-Preserved Retinex Model. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Sohel, F. A Pixel Distribution Remapping and Multi-Prior Retinex Variational Model for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 7838–7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Feng, Y.; Cai, L.; Zhuang, P. Underwater Image Enhancement via Principal Component Fusion of Foreground and Background. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 10930–10943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Xiao, Q.; Dian, S. Underwater Image Enhancement Based on Multichannel Adaptive Compensation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Su, H.; Fan, B.; Yang, N.; Zhong, S.; Yin, J. Underwater Image Enhancement Based on Red Channel Correction and Improved Multiscale Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.; Bhandari, A.K. CBLA: Color-Balanced Locally Adjustable Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Yin, S.; Deng, Z.; Yang, Y.H. A multi-level wavelet-based underwater image enhancement network with color compensation prior. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Liang, J. Underwater Image Enhancement via Wavelet Decomposition Fusion of Advantage Contrast. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 7807–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, L. MUFFNet: Lightweight dynamic underwater image enhancement network based on multi-scale frequency. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1541265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Yuan, J.; Ma, T.; Ma, L.; Jia, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y. Degradation-Decoupled and semantic-aggregated cross-space fusion for underwater image enhancement. Inf. Fusion 2025, 118, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Eom, I.K. Underwater image enhancement using adaptive standardization and normalization networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-To-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, D.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Dual-Domain Adaptive Synergy GAN for Enhancing Low-Light Underwater Images. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wu, X.; Fan, S.; Wei, S.; Gowing, G. INGC-GAN: An Implicit Neural-Guided Cycle Generative Approach for Perceptual-Friendly Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 10084–10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. DiffUIE: Learning Latent Global Priors in Diffusion Models for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 2516–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, S.; Liang, H.; Bai, S.; Jiang, F.; Hussain, A. PAFPT: Progressive aggregator with feature prompted transformer for underwater image enhancement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 262, 125539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Li, J.; Feng, L. Underwater variable zoom: Depth-guided perception network for underwater image enhancement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 259, 125350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xu, H.; Jiang, G.; Yu, M.; Chen, Y.; Luo, T.; Song, Y. Frequency domain-based latent diffusion model for underwater image enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 160, 111198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, Y.; Guan, B.; Zeng, X.; Guo, L. Unsupervised Underwater Image Enhancement Based on Disentangled Representations via Double-Order Contrastive Loss. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, J. MDA-Net: A Multidistribution Aware Network for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Chu, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhai, Z.; Wang, D. NPT-UL: An Underwater Image Enhancement Framework Based on Nonphysical Transformation and Unsupervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Pun, C.M. Underwater Image Restoration Through a Prior Guided Hybrid Sense Approach and Extensive Benchmark Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 4784–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Chen, S.; Hao, L.Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, L. FBDPN: CNN-Transformer hybrid feature boosting and differential pyramid network for underwater object detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 256, 124978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, J.; Ashok Kumar, L. An explainable artificial intelligence driven fall system for sensor data analysis enhanced by butterworth filtering. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurinjimalar, R.; Pradeep, J.; Harikrishnan, M. Underwater Image Enhancement Using Gaussian Pyramid, Laplacian Pyramid and Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd World Conference on Applied Intelligence and Computing (AIC), Gwalior, India, 27–28 July 2024; pp. 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.J.; Xia, Y.; Sattar, J. Fast Underwater Image Enhancement for Improved Visual Perception. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 3227–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhu, C.; Bian, L. U-Shape Transformer for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 3066–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, C.; Ren, W.; Cong, R.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Tao, D. An Underwater Image Enhancement Benchmark Dataset and Beyond. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 4376–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.; Wang, D.; Fan, X.; Wang, Z. A Dataset and Benchmark of Underwater Object Detection for Robot Picking. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Shenzhen, China, 5–9 July 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Deep Features as a Perceptual Metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Panetta, K.; Gao, C.; Agaian, S. Human-Visual-System-Inspired Underwater Image Quality Measures. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2016, 41, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Sowmya, A. An Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation Metric. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 6062–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, A.; Soundararajan, R.; Bovik, A.C. Making a “Completely Blind” Image Quality Analyzer. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2013, 20, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wu, R.; Jin, X.; Han, L.; Zhang, W.; Chai, Z.; Li, C. Underwater Ranker: Learn Which Is Better and How to Be Better. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhuang, P.; Li, G.; Pan, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement via Weighted Wavelet Visual Perception Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Xu, L.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, H. HFM: A hybrid fusion method for underwater image enhancement. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Wu, J.; Porikli, F.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement with Hyper-Laplacian Reflectance Priors. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 5442–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement by Attenuated Color Channel Correction and Detail Preserved Contrast Enhancement. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 47, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhuang, P.; Sun, H.H.; Li, G.; Kwong, S.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement via Minimal Color Loss and Locally Adaptive Contrast Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 3997–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jin, S.; Zhuang, P.; Liang, Z.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement via Piecewise Color Correction and Dual Prior Optimized Contrast Enhancement. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cai, Z.; Cao, W. TEBCF: Real-World Underwater Image Texture Enhancement Model Based on Blurriness and Color Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.T.; Chen, Y.R.; Chen, G.R.; Liao, C.J. Histoformer: Histogram-Based Transformer for Efficient Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 50, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Negi, A.; Kulkarni, A.; Phutke, S.S.; Vipparthi, S.K.; Murala, S. Phaseformer: Phase-Based Attention Mechanism for Underwater Image Restoration and Beyond. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 28 February–4 March 2025; pp. 9618–9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Zheng, F.; Pun, C.M. Underwater Image Restoration via Polymorphic Large Kernel CNNs. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, X.; Luo, T.; Zhou, J. Underwater Image Enhancement with Cascaded Contrastive Learning. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 1512–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X.; Ma, K.K. Uncertainty Inspired Underwater Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Proceedings, Part XVIII; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Lin, H.; Yang, Y.; Chai, S.; Sun, L.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X. Unsupervised Underwater Image Restoration: From a Homology Perspective. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Li, K.; Zheng, H.; Gao, X.; Hou, G.; Sun, K. SGUIE-Net: Semantic Attention Guided Underwater Image Enhancement with Multi-Scale Perception. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 6816–6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

| Methods | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | FSIM ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | Params (M) ↓ | FLOPs (G) ↓ | Time (s) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFAC [25] | 15.73 ± 3.21 | 0.66 ± 0.14 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 0.35 ± 0.10 | - | - | 0.38 |

| WWPF [57] | 17.48 ± 3.59 | ±0.73 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.28 ± 0.11 | - | - | 0.26 |

| HFM [58] | 17.31 ± 3.18 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | - | - | 0.53 |

| HLRP [59] | 12.80 ± 1.97 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.05 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | - | - | 0.01 |

| ACDC [60] | 16.63 ± 2.90 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.11 | - | - | 0.22 |

| MMLE [61] | 17.80 ± 3.73 | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.11 | - | - | 0.08 |

| PCDE [62] | 15.40 ± 2.96 | 0.62 ± 0.14 | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | - | - | 0.29 |

| TEBCF [63] | 17.90 ± 2.30 | 0.69 ± 0.12 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | - | - | 1.24 |

| CycleGAN [29] | 23.91 ± 4.72 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 22.76 | 99.364 | 0.03 |

| U-Shape [49] | 24.32 ± 3.87 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 31.59 | 26.10 | 0.05 |

| FUnIE-GAN [48] | 21.42 ± 3.49 | 0.79 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 3.59 | 26.72 | 0.06 |

| Histoformer [64] | 13.96 ± 2.25 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 25.71 | 44.42 | 0.03 |

| Phaseformer [65] | 24.13 ± 3.17 | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 1.78 | 14.12 | 0.03 |

| UIR-PolyKernel [66] | 22.19 ± 4.62 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 1.89 | 13.68 | 0.01 |

| CCL-Net [67] | 23.81 ± 5.39 | 0.83 ± 0.20 | 0.91 ± 0.10 | 0.23 ± 0.16 | 0.55 | 37.36 | 0.06 |

| PUIE-Net [68] | 24.40 ± 3.78 | 0.91 ± 0.08 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 0.83 | 150.69 | 0.13 |

| USUIR [69] | 18.79 ± 2.86 | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.08 | 0.23 | 14.88 | 0.01 |

| SGUIE [70] | 24.13 ± 4.50 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | 18.63 | 20.16 | 0.02 |

| PMSPNet | 25.51 ± 3.98 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | 4.44 | 26.77 | 0.01 |

| Methods | UIQM ↑ | UCIQE ↑ | NIQE ↓ | URANKER ↑ | Laplacian ↑ | Tenengrad ↑ | Brenner ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFAC [25] | 3.16 ± 0.33 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 6.02 ± 3.46 | 2.49 ± 0.89 | 0.11 ± 0.18 | 0.53 ± 0.23 | 2044.20 ± 1559.13 |

| WWPF [57] | 2.85 ± 0.40 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 5.43 ± 2.20 | 2.50 ± 0.741 | 0.05 ± 0.08 | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 1291.93 ± 911.55 |

| HFM [58] | 2.91 ± 0.37 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 5.49 ± 2.02 | 2.35 ± 0.81 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 662.62 ± 639.15 |

| HLRP [59] | 2.62 ± 0.67 | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 5.78 ± 2.25 | 1.69 ± 0.96 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.09 | 1016.97 ± 489.98 |

| ACDC [60] | 3.34 ± 0.20 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 5.24 ± 1.78 | 2.68 ± 0.76 | 0.04 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.15 | 990.85 ± 790.32 |

| MMLE [61] | 2.77 ± 0.41 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 5.56 ± 2.42 | 2.53 ± 0.86 | 0.07 ± 0.10 | 0.46 ± 0.19 | 1504.57 ± 1072.266 |

| PCDE [62] | 2.66 ± 0.68 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 5.50 ± 1.98 | 2.59 ± 0.74 | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.50 ± 0.17 | 1671.21 ± 995.43 |

| TEBCF [63] | 3.00 ± 0.35 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 5.60 ± 1.75 | 2.42 ± 0.69 | 0.049 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.14 | 1274.67 ± 699.73 |

| CycleGAN [29] | 3.19 ± 0.42 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 4.62 ± 1.30 | 1.50 ± 0.81 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.10 | 448.48 ± 291.55 |

| U-Shape [49] | 3.10 ± 0.46 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 5.05 ± 1.37 | 1.35 ± 0.74 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 313.03 ± 202.13 |

| FUnIE-GAN [48] | 3.10 ± 0.43 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 4.17 ± 0.90 | 1.80 ± 0.78 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 607.95 ± 504.67 |

| Histoformer [64] | 3.09 ± 0.27 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 12.00 ± 3.09 | 0.74 ± 0.54 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 99.17 ± 76.09 |

| Phaseformer [65] | 2.77 ± 0.39 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | 7.75 ± 6.61 | 1.26 ± 0.79 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.10 | 399.73 ± 353.68 |

| UIR-PolyKernel [66] | 2.91 ± 0.62 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 5.09 ± 1.38 | 1.18 ± 0.99 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.13 | 435.62 ± 447.07 |

| CCL-Net [67] | 3.03 ± 0.48 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 5.56 ± 2.05 | 1.46 ± 0.76 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.11 | 488.43 ± 408.52 |

| PUIE-Net [68] | 3.00 ± 0.51 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 5.55 ± 1.85 | 1.42 ± 0.85 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 430.14 ± 375.36 |

| USUIR [69] | 2.96 ± 0.30 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 4.80 ± 1.15 | 1.51 ± 0.82 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.11 | 528.35 ± 372.24 |

| SGUIE [70] | 2.96 ± 0.56 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 5.46 ± 1.52 | 1.31 ± 0.90 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 350.12 ± 326.33 |

| PMSPNet | 3.46 ± 0.41 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 5.30 ± 1.61 | 1.73 ± 0.79 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 319.80 ± 254.67 |

| Methods | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | FSIM ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | UIQM ↑ | UCIQE ↑ | URANKER ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFAC [25] | 13.24 ± 2.43 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 0.45 ± 0.10 | 2.81 ± 0.26 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 2.97 ± 0.90 |

| WWPF [57] | 14.62 ± 2.83 | 0.60 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.09 | 2.68 ± 0.33 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 2.16 ± 0.81 |

| HFM [58] | 15.13 ± 2.74 | 0.66 ± 0.10 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.11 | 2.93 ± 0.25 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 2.44 ± 0.99 |

| HLRP [59] | 11.41 ± 1.86 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.06 | 2.65 ± 0.59 | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 2.09 ± 0.99 |

| ACDC [60] | 14.42 ± 2.61 | 0.60 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 3.34 ± 0.15 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 2.98 ± 0.81 |

| MMLE [61] | 14.12 ± 2.69 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.72 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 2.56 ± 0.31 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 2.78 ± 0.98 |

| PCDE [62] | 13.55 ± 2.48 | 0.52 ± 0.13 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.11 | 2.37 ± 0.56 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 2.97 ± 0.80 |

| TEBCF [63] | 17.07 ± 2.55 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 2.82 ± 0.36 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 2.59 ± 0.81 |

| CycleGAN [29] | 22.68 ± 3.52 | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 3.11 ± 0.50 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 1.30 ± 0.85 |

| U-Shape [49] | 24.92 ± 3.78 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 2.97 ± 0.62 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 1.18 ± 0.84 |

| FUnIE-GAN [48] | 24.06 ± 2.60 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 2.88 ± 0.57 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 1.36 ± 0.82 |

| Histoformer [64] | 14.82 ± 2.88 | 0.33 ± 0.14 | 0.65 ± 0.07 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 3.12 ± 0.23 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.50 |

| Phaseformer [65] | 23.58 ± 2.64 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 2.63 ± 0.51 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.98 ± 0.81 |

| UIR-PolyKernel [66] | 24.92 ± 3.86 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 2.85 ± 0.74 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 1.37 ± 0.90 |

| CCL-Net [67] | 24.55 ± 3.17 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 2.97 ± 0.60 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 1.34 ± 0.80 |

| PUIE-Net [68] | 24.71 ± 2.70 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 2.97 ± 0.61 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.76 |

| USUIR [69] | 17.53 ± 2.47 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 2.82 ± 0.22 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 1.78 ± 0.89 |

| SGUIE [70] | 25.48 ± 3.23 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 2.83 ± 0.71 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.87 |

| PMSPNet | 25.81 ± 3.22 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 3.09 ± 0.46 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 1.16 ± 0.78 |

| Methods | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | FSIM ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | UIQM ↑ | UCIQE ↑ | URANKER ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFAC [25] | 15.35 ± 3.09 | 0.61 ± 0.14 | 0.73 ± 0.09 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 2.76 ± 0.45 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 2.55 ± 0.84 |

| WWPF [57] | 17.51 ± 3.44 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 2.76 ± 0.41 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 2.59 ± 0.65 |

| HFM [58] | 17.63 ± 2.93 | 0.74 ± 0.11 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 2.80 ± 0.31 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 2.41 ± 0.73 |

| HLRP [59] | 13.04 ± 1.87 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 2.80 ± 0.58 | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 1.65 ± 0.88 |

| ACDC [60] | 16.96 ± 2.63 | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 0.33 ± 0.10 | 3.34 ± 0.18 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 2.63 ± 0.72 |

| MMLE [61] | 17.59 ± 3.15 | 0.69 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 2.55 ± 0.44 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 2.59 ± 0.80 |

| PCDE [62] | 15.25 ± 2.30 | 0.59 ± 0.11 | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 2.32 ± 0.57 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 2.75 ± 0.69 |

| TEBCF [63] | 17.95 ± 2.05 | 0.68 ± 0.12 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 2.93 ± 0.33 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 2.58 ± 0.64 |

| CycleGAN [29] | 24.93 ± 4.32 | 0.85 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 3.21 ± 0.37 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 1.63 ± 0.71 |

| U-Shape [49] | 24.94 ± 3.54 | 0.84 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 3.10 ± 0.41 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 1.38 ± 0.61 |

| FUnIE-GAN [48] | 21.47 ± 3.32 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 3.09 ± 0.38 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 1.84 ± 0.64 |

| Histoformer [64] | 14.05 ± 2.04 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 0.65 ± 0.07 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 3.07 ± 0.28 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.70 ± 0.56 |

| Phaseformer [65] | 24.64 ± 3.14 | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 2.79 ± 0.33 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 1.29 ± 0.70 |

| UIR-PolyKernel [66] | 22.22 ± 4.20 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 2.91 ± 0.54 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 1.16 ± 0.90 |

| CCL-Net [67] | 25.15 ± 4.45 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 3.02 ± 0.43 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 1.52 ± 0.67 |

| PUIE-Net [68] | 26.21 ± 3.63 | 0.90 ± 0.09 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 3.06 ± 0.44 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 1.39 ± 0.65 |

| USUIR [69] | 18.86 ± 2.74 | 0.80 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 2.96 ± 0.29 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 1.44 ± 0.75 |

| SGUIE [70] | 24.59 ± 4.40 | 0.87 ± 0.10 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | 2.96 ± 0.49 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 1.37 ± 0.78 |

| PMSPNet | 26.46 ± 3.91 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 3.31 ± 0.38 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 1.51 ± 0.70 |

| Methods | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | FSIM ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | UIQM ↑ | UCIQE ↑ | URANKER ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFAC [25] | 15.39 ± 2.25 | 0.66 ± 0.13 | 0.74 ± 0.10 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 2.79 ± 0.52 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 2.39 ± 0.79 |

| WWPF [57] | 17.52 ± 2.71 | 0.76 ± 0.10 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 2.75 ± 0.54 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 2.54 ± 0.89 |

| HFM [58] | 17.76 ± 3.44 | 0.79 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.14 | 2.93 ± 0.52 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 2.33 ± 0.98 |

| HLRP [59] | 13.33 ± 1.58 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 3.10 ± 0.67 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.88 |

| ACDC [60] | 17.70 ± 3.20 | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 0.27 ± 0.12 | 3.39 ± 0.35 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 2.57 ± 0.85 |

| MMLE [61] | 17.35 ± 2.91 | 0.73 ± 0.11 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.11 | 2.46 ± 0.57 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 2.56 ± 0.96 |

| PCDE [62] | 15.20 ± 3.67 | 0.61 ± 0.19 | 0.75 ± 0.12 | 0.38 ± 0.13 | 2.27 ± 0.94 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 2.69 ± 0.81 |

| TEBCF [63] | 17.68 ± 2.51 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.84 ± 0.11 | 0.25 ± 0.10 | 2.84 ± 0.38 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 2.60 ± 0.87 |

| CycleGAN [29] | 19.44 ± 4.28 | 0.77 ± 0.10 | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.27 ± 0.09 | 3.19 ± 0.50 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 1.15 ± 1.02 |

| U-Shape [49] | 20.72 ± 3.59 | 0.81 ± 0.10 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 3.25 ± 0.43 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 1.39 ± 1.09 |

| FUnIE-GAN [48] | 18.02 ± 2.10 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 3.42 ± 0.21 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 2.09 ± 1.06 |

| Histoformer [64] | 12.50 ± 1.62 | 0.23 ± 0.13 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 3.15 ± 0.22 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.47 |

| Phaseformer [65] | 22.41 ± 3.28 | 0.68 ± 0.15 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.09 | 2.82 ± 0.47 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 1.48 ± 1.03 |

| UIR-PolyKernel [66] | 17.72 ± 4.06 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.11 | 2.96 ± 0.78 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 1.07 ± 1.44 |

| CCL-Net [67] | 16.93 ± 5.99 | 0.64 ± 0.31 | 0.79 ± 0.17 | 0.38 ± 0.27 | 3.16 ± 0.52 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 1.32 ± 0.97 |

| PUIE-Net [68] | 22.43 ± 3.95 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 3.09 ± 0.49 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 1.45 ± 1.27 |

| USUIR [69] | 19.95 ± 3.41 | 0.82 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.24 ± 0.10 | 3.18 ± 0.35 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 1.56 ± 0.98 |

| SGUIE [70] | 20.42 ± 4.47 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 3.10 ± 0.63 | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 1.25 ± 1.35 |

| PMSPNet | 22.43 ± 3.37 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 3.27 ± 0.39 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 1.53 ± 1.08 |

| ButterWorth | Deformable | PMPB | PFFB | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | FSIM ↑ | UIQM ↑ | UCIQE ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 25.98 ± 4.20 | 0.88 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 3.08 ± 0.40 | 0.39 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 17.18 ± 5.14 | 0.73 ± 0.13 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 2.31 ± 0.84 | 0.41 ± 0.08 |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 25.99 ± 4.29 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 3.09 ± 0.39 | 0.40 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 24.78 ± 4.07 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 3.08 ± 0.41 | 0.39 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 25.51 ± 3.98 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 3.46 ± 0.41 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

| Charbonnier | FFT | LAB | LCH | VGG | Color | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | FSIM ↑ | UIQM ↑ | UCIQE ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 24.00 ± 3.98 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 2.90 ± 0.45 | 0.41 ± 0.07 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 21.27 ± 4.31 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 2.95 ± 0.41 | 0.35 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 21.43 ± 4.21 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 3.08 ± 0.37 | 0.35 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 22.53 ± 4.36 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 3.08 ± 0.37 | 0.37 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 24.06 ± 3.84 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 3.08 ± 0.38 | 0.39 ± 0.06 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 25.51 ± 3.80 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 3.46 ± 0.41 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Progressive Multi-Scale Perception Network for Non-Uniformly Blurred Underwater Image Restoration. Sensors 2025, 25, 5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25175439

Kong D, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Wang Y, Wang Y. Progressive Multi-Scale Perception Network for Non-Uniformly Blurred Underwater Image Restoration. Sensors. 2025; 25(17):5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25175439

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Dechuan, Yandi Zhang, Xiaohu Zhao, Yanyan Wang, and Yanqiang Wang. 2025. "Progressive Multi-Scale Perception Network for Non-Uniformly Blurred Underwater Image Restoration" Sensors 25, no. 17: 5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25175439

APA StyleKong, D., Zhang, Y., Zhao, X., Wang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2025). Progressive Multi-Scale Perception Network for Non-Uniformly Blurred Underwater Image Restoration. Sensors, 25(17), 5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25175439