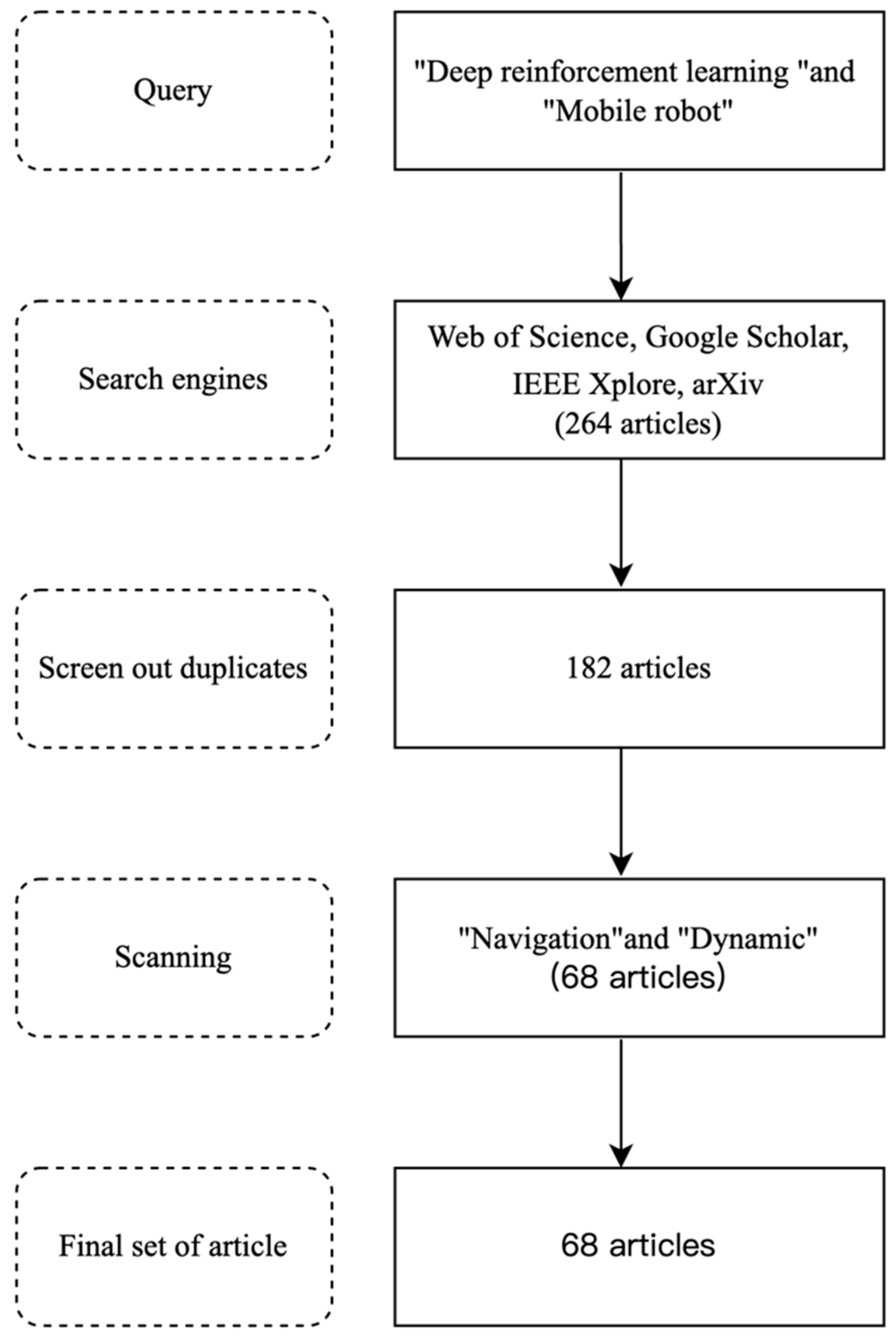

Deep Reinforcement Learning of Mobile Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environment: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theories and Comparisons of Deep Reinforcement Learning Methods

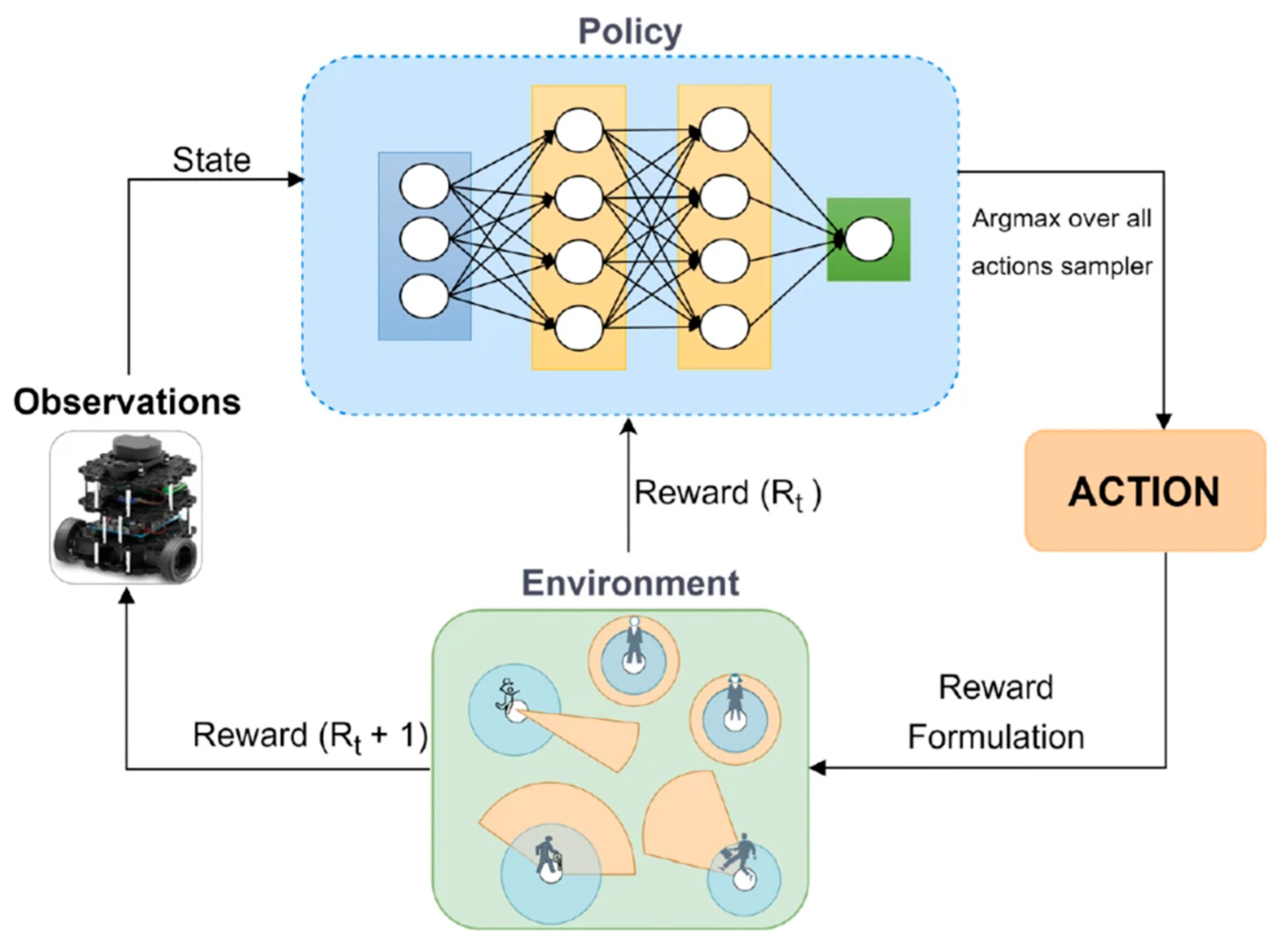

2.1. Theoretical Framework of Deep Reinforcement Learning

2.2. Comparison of DRL with Classical and Other Learning-Based Navigation Methods

| Ref. | Problem Type | Typical Scenario | DRL Suitability | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | Static path planning | Indoor warehouse with fixed layout | Not preferred | Traditional planners (A*, Dijkstra) are fast and optimal |

| [55] | Dynamic obstacle avoidance | Urban sidewalk with moving pedestrians | Suitable | DRL adapts to real-time interactions and uncertainties |

| [56] | Multi-agent coordination | Multi-robot logistics in shared space | Suitable | DRL enables decentralized adaptive policies |

| [57] | Deterministic rules and known map | Factory floor with preprogrammed signals | Not preferred | Rule-based FSMs are reliable, interpretable, and efficient |

| [58] | Sensor-constrained, low-latency tasks | Drone hovering in tight indoor space | Not preferred | DRL inference may exceed timing constraints; PID or MPC preferable |

| [59] | Unstructured outdoor exploration | Off-road navigation with unknown terrain | Suitable | DRL handles partial observability and long-term reasoning |

2.3. Comparison of Classical DRL Methods

| Category | Ref. | Method | Year | Computation Cost | Sample Efficiency | Robustness to Environmental Changes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

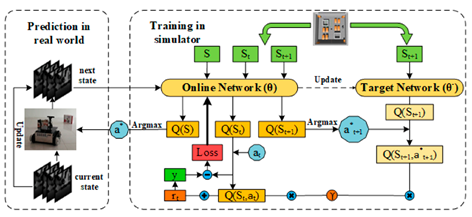

| Value-Based DRL Methods | [33,58,63] | Deep Q-Network (DQN) | 2013 | Medium | Low | Low | Addresses the scalability issue of Q-learning by using deep neural networks for function approximation. Stabilizes learning through techniques like experience replay and a target network. | Prone to overestimation bias in Q-value estimation. High computational complexity due to the use of neural networks. Sensitive to hyperparameter settings, such as learning rate and replay buffer size. |

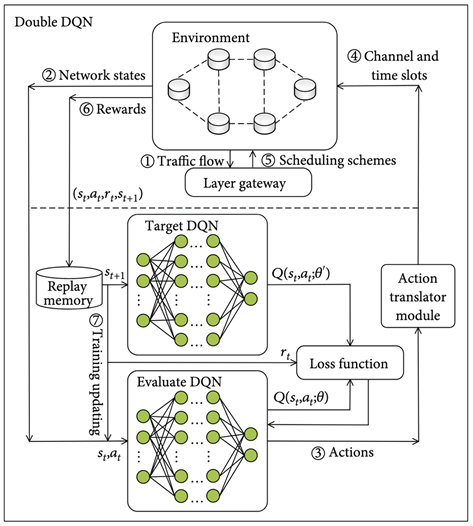

| [57,60,64] | Double Deep Q-Network (Double DQN) | 2015 | Medium | Medium | Medium | Reduces overestimation bias by decoupling action selection and value estimation. Improves stability and accuracy in policy learning compared to DQN. | Increases computational complexity due to maintaining two Q-networks. Sensitive to hyperparameter tuning, especially learning rates and update frequencies. | |

| [61,65] | Dueling Deep Q-Network (Dueling DQN) | 2016 | Medium | Medium | Medium | Separates state value and action advantage, enabling more precise Q-value estimation. Enhances learning efficiency by focusing on state evaluation in scenarios with minimal action-value differences. | Increased computational complexity due to the additional network architecture. Sensitive to hyperparameter tuning and network design choices. | |

| Policy-Based DRL Methods | [8,37] | Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) | 2015 | High | Medium | High | Ensures stable and monotonic policy improvement through trust region constraints. Effective for high-dimensional or continuous action spaces. | Computationally expensive due to solving constrained optimization problems. Complex implementation compared to simpler policy gradient methods. |

| [37,66] | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | 2017 | Medium | High | Medium | Simplifies trust region optimization with a clipping mechanism, improving computational efficiency. Balances policy stability and learning efficiency, making it suitable for real-time tasks. | Sensitive to hyperparameter tuning, particularly the clipping threshold. May still face performance degradation in highly complex environments. | |

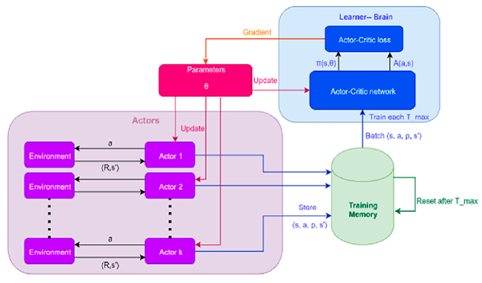

| Hybrid-Based DRL Methods | [67,68] | Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) | 2016 | Low | Medium | Medium | Improves training efficiency through asynchronous updates from multiple parallel agents. Eliminates the need for experience replay, reducing memory requirements. | Lower sample efficiency compared to methods using experience replay. Requires significant computational resources for parallel processing. |

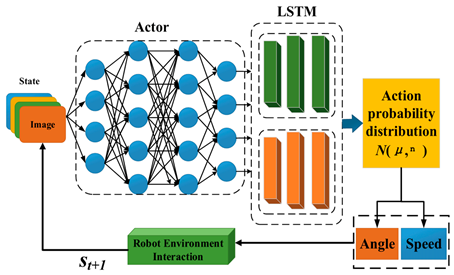

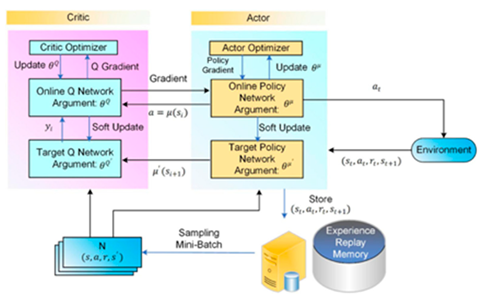

| [16,69] | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) | 2015 | Medium | Medium | Low | Handles high-dimensional continuous action spaces effectively. Combines the strengths of policy gradient and value-based methods using an actor-critic framework. | Prone to overfitting and instability due to deterministic policies. Requires extensive hyperparameter tuning and is sensitive to noise settings. | |

| [36,70] | Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) | 2018 | High | Medium | High | Encourages exploration with the maximum entropy framework, improving robustness. Reduces overestimation bias using dual Q-networks, enhancing stability. | Computationally intensive due to simultaneous training of multiple networks. Performance is highly sensitive to the entropy weighting coefficient. | |

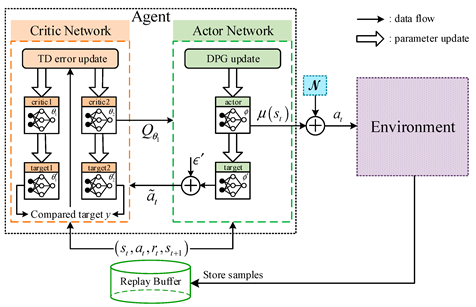

| [35,71] | Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) | 2018 | Medium | Medium | High | Reduces overestimation bias with twin Q-networks for more accurate value estimation. Improves stability with delayed policy updates and target policy smoothing. | Computationally expensive due to training multiple networks. Sensitive to hyperparameter tuning, such as update delays and noise settings. |

3. Key Technologies of Deep Reinforcement Learning in Dynamic Environment Navigation

3.1. Adaptability and Robustness in Dynamic Environments

3.2. Multimodal Perception and Data Fusion

3.3. Navigation Techniques for Different Task Scenarios

3.4. Analysis of DRL Research Applications

| Application Scenario | Ref. | Algorithm | Perception Type | Training Times | Success Rate | Max. Reward | Avg. Reward | Real System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor | [79] | DWA-RL | L | — | 54% | — | — | Y |

| [89] | LND3QN | V | 1500 episodes | — | 100 | 82 | Y | |

| [91] | A2C | L | — | 85% | — | — | Y | |

| [82] | A New Reward Function | V | — | — | — | — | N | |

| [83] | GA3C | L | 6,000,000 episodes | — | 3,000,000 | About 2,500,000 | N | |

| [92] | DQN and DDQN | L, V | 800 episodes | — | 1500 | 1000 | Y | |

| [10] | DDPG and DQN | — | 800,000 steps | — | 0 | About 0 | N | |

| [93] | DS-DSAC | L | 200,000 steps | — | 20 | About 19 | Y | |

| [94] | GD-RL | L | — | 60% | — | — | Y | |

| [95] | DQN + PTZ | V | 10,000 episodes | — | — | — | N | |

| [87] | Context-Aware DRL Policy | L | 2000 steps | 98% | — | — | Y | |

| [96] | β-Decay TL | L | 2500 episodes | 100% | — | — | N | |

| [86] | DDPG + PER | V | 80,000 steps | — | 10 | About 8 | Y | |

| [97] | Improved TD3 | L | 1200 episodes | 92.8% | — | — | N | |

| Outdoor | [80] | HGAT-DRL | — | — | 90% | — | — | N |

| [98] | TERP | V | — | 82% | — | — | Y | |

| [99] | re-DQN | V | — | — | — | — | Y | |

| [89] | TCAMD | — | 2000 episodes | — | About 49 | 50 | N | |

| [100] | RL-Based MIPP | — | 20,000 episodes | — | About 29 | 30 | N | |

| Other | [101] | DDPG | — | 800 episodes | — | About 2000 | 2000 | N |

| [88] | CAM-RL | — | — | — | — | — | N | |

| [102] | DODPG | V | 600 episodes | — | About −500 | 0 | Y |

4. Future Research Directions of Deep Reinforcement Learning in Dynamic Navigation

4.1. DRL Adaptability and Decision Efficiency in Dynamic Environments

4.2. Optimizing Multimodal Perception Data Fusion Techniques

4.3. Developing Multi-Robot Collaborative Learning Frameworks

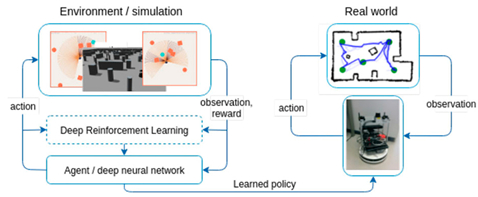

4.4. Facilitating Sim-to-Real Transfer and Deployment

4.5. Strengthening Safety and Explainability

4.6. Cross-Domain Applications and Extensions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| SLAM | Simultaneous localization and mapping |

| RRT | Rapidly exploring random tree |

| MDPs | Markov decision processes |

| RL | Reinforcement learning |

| DNNs | Deep neural networks |

| DQN | Deep Q-network |

| DDPG | Deep deterministic policy gradient |

| TD3 | Twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient |

| PPO | Proximal policy optimization |

| SAC | Soft actor-critic |

| DWA | Dynamic window approach |

| MARL | Multi-agent reinforcement learning |

| Double DQN | Double deep Q-network |

| Dueling DQN | Dueling deep Q-network |

| TRPO | Trust region policy optimization |

| A3C | Asynchronous advantage actor-critic |

| KL divergence | Kullback–Leibler divergence |

| A* | A-Star |

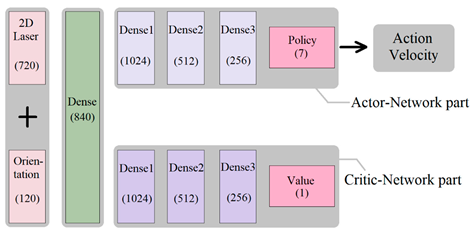

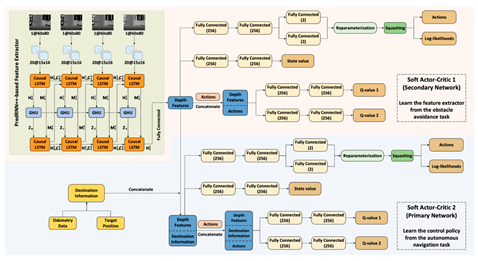

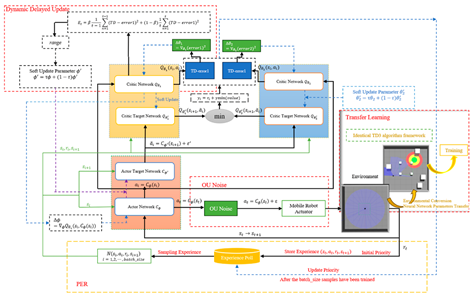

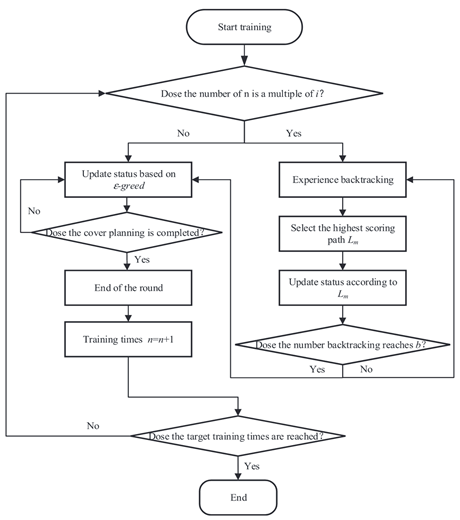

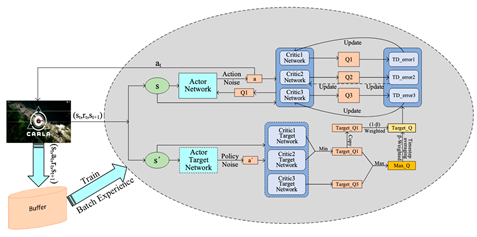

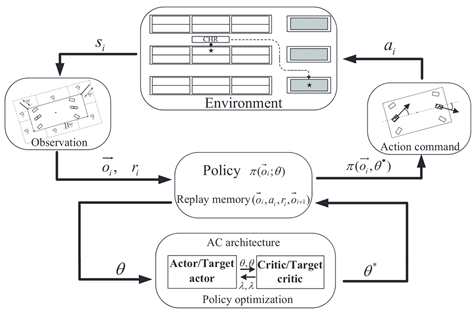

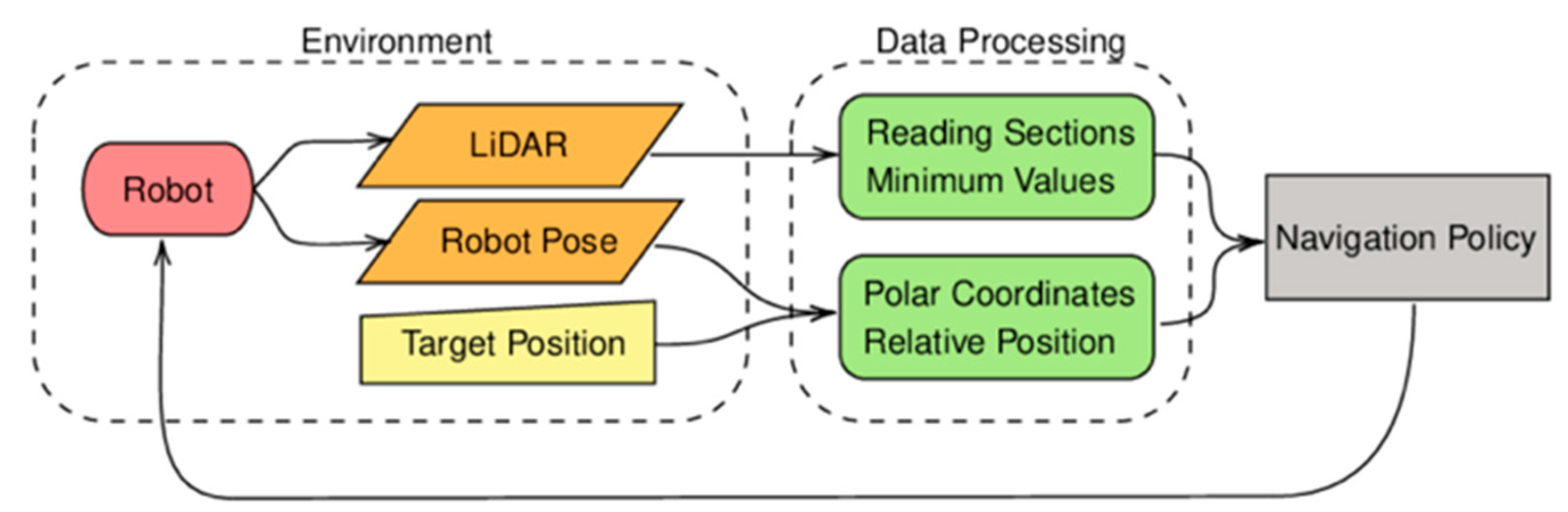

Appendix A

| Ref. | Method | Framework/Flowchart |

|---|---|---|

| [33,58] | Deep Q-Network (DQN) |  |

| [57,60] | Double Deep Q-Network (Double DQN) |  |

| [61,65] | Dueling Deep Q-Network (Dueling DQN) |  |

| [8,37] | Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) |  |

| [37,66] | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) |  |

| [67,68] | Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) |  |

| [16,69] | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) |  |

| [36,70] | Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) |  |

| [35,71] | Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) |  |

| [79] | DWA-RL |  |

| [89] | LND3QN |  |

| [91] | A2C |  |

| [82] | A New Reward Function |  |

| [83] | GA3C |  |

| [92] | DQN and DDQN |  |

| [10] | DDPG and DQN |  |

| [93] | DS-DSAC |  |

| [94] | GD-RL |  |

| [95] | DQN + PTZ |  |

| [87] | Context-Aware DRL Policy |  |

| [96] | β-Decay TL |  |

| [86] | DDPG + PER |  |

| [97] | Improved TD3 |  |

| [80] | HGAT-DRL |  |

| [98] | TERP |  |

| [99] | re-DQN |  |

| [89] | TCAMD |  |

| [100] | RL-Based MIPP |  |

| [79] | CAM-RL |  |

| [92] | DODPG |  |

References

- Prasuna, R.G.; Potturu, S.R. Deep Reinforcement Learning in Mobile Robotics—A Concise Review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 70815–70836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, B.; Khatib, O. Robotics and the Handbook. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-3-319-32552-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Knoll, A.C.; Zhou, M. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Trajectory Planning Under Uncertain Constraints. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 883562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasti, S.M.; Chishti, M.A. A Review of AI-Enhanced Navigation Strategies for Mobile Robots in Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASU International Conference in Emerging Technologies for Sustainability and Intelligent Systems (ICETSIS), Manama, Bahrain, 28–29 January 2024; pp. 1239–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Junginger, S.; Huang, J.; Jin, K.; Thurow, K. Deep Learning for Visual SLAM in Transportation Robotics: A Review. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2019, 1, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValle, S.M. Planning Algorithms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-139-45517-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, S.; Banerjee, H.; Tse, Z.T.H.; Ren, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Soft, Flexible Robots: Brief Review with Impending Challenges. Robotics 2019, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, R.; Zhang, Y. Motion Planning for Mobile Robots—Focusing on Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 69061–69081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devo, A.; Mezzetti, G.; Costante, G.; Fravolini, M.L.; Valigi, P. Towards Generalization in Target-Driven Visual Navigation by Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 1546–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, F.; Hermosilla, G.; Farias, G.; Fabregas, E.; Montenegro, G. Position Control of a Mobile Robot through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, B.; Incremona, G.P.; Piastra, M.; Ferrara, A. Self-Configuring Robot Path Planning With Obstacle Avoidance via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2021, 5, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candra, A.; Budiman, M.A.; Hartanto, K. Dijkstra’s and A-Star in Finding the Shortest Path: A Tutorial. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Business Analytics (DATABIA), Medan, Indonesia, 16–17 July 2020; pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-Level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, J.; Bagnell, J.A.; Peters, J. Reinforcement Learning in Robotics: A Survey. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1238–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, L.Z.; Xie, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y. Deep Learning-Based Robot Vision: High-End Tools for Smart Manufacturing. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2022, 25, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, V.R.F.; Neto, A.A.; Freitas, G.M.; Mozelli, L.A. Generalization in Deep Reinforcement Learning for Robotic Navigation by Reward Shaping. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 6013–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning, 2nd ed.; An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-262-35270-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.; La, H. Review of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Robot Manipulation. In Proceedings of the 2019 Third IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC), Naples, Italy, 25–27 February 2019; pp. 590–595. [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa, L.C.; Basso, M.; Konzen, A.A.; De Freitas, E.P. Reinforcement Learning for Mobile Robotics Exploration: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 3796–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Jain, S.; Sharma, R.S. Path Planning for Fully Autonomous UAVs-a Taxonomic Review and Future Perspectives. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13356–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Saeedvand, S.; Hsu, C.-C. A Comprehensive Review of Mobile Robot Navigation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms in Crowded Environments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, H.A.; Gashler, M.S. Deep Learning in Robotics: A Review of Recent Research. Adv. Robot. 2017, 31, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, F.; Zhao, J. A Review of Deep Reinforcement Learning Exploration Methods: Prospects and Challenges for Application to Robot Attitude Control Tasks. In Cognitive Systems and Information Processing, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference, ICCSIP 2022, Fuzhou, China, 17–18 December 2022; Sun, F., Cangelosi, A., Zhang, J., Yu, Y., Liu, H., Fang, B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. A Review of Mobile Robot Path Planning Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2138, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, T. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Mobile Robot Navigation: A Review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ye, D.; Kang, J.; Wu, M.; Yu, R. A Cloud-Edge Collaborative Architecture for Multimodal LLMs-Based Advanced Driver Assistance Systems in IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 13208–13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Yau, W.-Y.; Wan, K.-W. A Brief Survey: Deep Reinforcement Learning in Mobile Robot Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2020 15th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Kristiansand, Norway, 9–13 November 2020; pp. 592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. A Markovian Decision Process. J. Math. Mech. 1957, 6, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Graves, A.; Antonoglou, I.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.5602. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the Game of Go with Deep Neural Networks and Tree Search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Badia, A.P.; Mirza, M.; Graves, A.; Lillicrap, T.P.; Harley, T.; Silver, D.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Asynchronous Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.01783. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, T.; Wang, M. Optimal Ancillary Service Disaggregation for EV Charging Station Aggregators: A Hybrid On–Off Policy Reinforcement Learning Framework, 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5100232 (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.09477. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.01290. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Levine, S.; Moritz, P.; Jordan, M.I.; Abbeel, P. Trust Region Policy Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1502.05477. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S.; Nguyen, T.A.; Choi, E.; Min, D. Multi-Head Fusion-Based Actor-Critic Deep Reinforcement Learning with Memory Contextualisation for End-to-End Autonomous Navigation. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Guo, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Mobile Robot Navigation in Crowd Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR), New York, NY, USA, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Parooei, M.; Tale Masouleh, M.; Kalhor, A. MAP3F: A Decentralized Approach to Multi-Agent Pathfinding and Collision Avoidance with Scalable 1D, 2D, and 3D Feature Fusion. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2024, 17, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A Note on Two Problems in Connexion with Graphs. In Edsger Wybe Dijkstra: His Life, Work, and Legacy; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 45, pp. 287–290. ISBN 978-1-4503-9773-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.; Burgard, W.; Thrun, S. The Dynamic Window Approach to Collision Avoidance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 1997, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Tolani, V.; Davidson, J.; Levine, S.; Sukthankar, R.; Malik, J. Cognitive Mapping and Planning for Visual Navigation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1702.03920v3. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J.J. Past, Present, and Future of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Toward the Robust-Perception Age. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1309–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ma, R.; Oyekan, J. A Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Framework for Autonomous Aerial Navigation to Grasping Points on Loads. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 167, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yang, X.; Gao, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. Learning Efficient Multi-Agent Cooperative Visual Exploration. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfi, M.H. Autonomous Exploration and Mapping of Unknown Environments. Master’s Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Azar, A.T.; Sardar, M.Z.; Haider, Z.; Kamal, N.A. Exploring Reinforcement Learning Techniques in the Realm of Mobile Robotics. IJAAC 2024, 18, 10062261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Optimizing Deep Reinforcement Learning for Real-World Robotics: Challenges and Solutions. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Comput. Sci. Manag. Technol. 2024, 1, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiotras, P.; Gombolay, M.; Foerster, J. Editorial: Decision-Making and Planning for Multi-Agent Systems. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1422344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, J.; Szynkiewicz, W. Human-Aware Robot Trajectory Planning with Hybrid Candidate Generation: Leveraging a Pedestrian Motion Model for Diverse Trajectories. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Workshop on Robot Motion and Control (RoMoCo), Poznań, Poland, 2–4 July 2024; pp. 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya, H.; Dhabliya, D.; Jweeg, M.; Almusawi, M.; Naser, Z.L.; Hashem, A.; Jawad, A.Q. An Empirical Analysis of Various Techniques of Solving Obstacles through Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), Greater Noida, India, 14–15 May 2024; pp. 1169–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, S.; Meng, R.; Guo, J.; Cui, P.; Qiao, Z. Multi-Vehicle Collaborative Planning Technology under Automatic Driving. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.; Tan, J.; Liu, C.K.; Ha, S. Learning to Navigate Sidewalks in Outdoor Environments. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.05603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; An, Z.; Abrar, S.; Zhou, L. Large Language Models for Multi-Robot Systems: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.03814. [Google Scholar]

- Alsadie, D. A Comprehensive Review of AI Techniques for Resource Management in Fog Computing: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 118007–118059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Long, P.; Liu, W.; Pan, J. Distributed Multi-Robot Collision Avoidance via Deep Reinforcement Learning for Navigation in Complex Scenarios. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2020, 39, 856–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Zhou, C.; Ding, L. Deep Learning Technology for Construction Machinery and Robotics. Autom. Constr. 2023, 150, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselt, H.v.; Guez, A.; Silver, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning with Double Q-Learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2016, 30, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lou, P.; Yan, J.; Liu, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Path Planning for Mobile Robot in Unknown Environment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1576, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarnoja, T.; Ha, S.; Zhou, A.; Tan, J.; Tucker, G.; Levine, S. Learning to Walk via Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.11103v3. [Google Scholar]

- Deep Reinforcement Learning for Scheduling in an Edge Computing-Based Industrial Internet of Things. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355377739_Deep_Reinforcement_Learning_for_Scheduling_in_an_Edge_Computing-Based_Industrial_Internet_of_Things (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Hu, M.; Zhang, J.; Matkovic, L.; Liu, T.; Yang, X. Reinforcement Learning in Medical Image Analysis: Concepts, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2023, 24, e13898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wan, P.; Chang, L.; Deng, X. Dueling Deep Q-Networks for Social Awareness-Aided Spectrum Sharing. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, X.; Zhang, R.; Hou, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H. Energy Management of Integrated Energy System in the Park under Multiple Time Scales. AIMS Energy 2024, 12, 639–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Schaul, T.; Hessel, M.; Hasselt, H.V.; Lanctot, M.; de Freitas, N. Dueling Network Architectures for Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; Volume 48, pp. 1995–2003. Available online: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v48/wangf16.html (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Nakabi, T.A.; Toivanen, P. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Energy Management in a Microgrid with Flexible Demand. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 25, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Heidari, A.A.; Chen, H. An Enhanced Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm for Intelligent Control of Robotic Arms. Front. Neuroinform. 2023, 17, 1096053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Du, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J. Priority-Aware Task Offloading in Vehicular Fog Computing Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 16067–16081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, R.; Ren, T.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Application of Deep Reinforcement Learning in Reconfiguration Control of Aircraft Anti-Skid Braking System. Aerospace 2022, 9, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, D.; Solano, J.; Beltrán, C. A Comparison Study between Traditional and Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Algorithms for Indoor Autonomous Navigation in Dynamic Scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23, 9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, D. Physics-Based Character Controllers with Reinforcement Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, B.; Wei, C.; Ji, Z. Deep Reinforcement Learning with Multiple Unrelated Rewards for AGV Mapless Navigation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 4323–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lin, K.; Jain, A.K.; Zhou, J. Transfer Learning in Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 13344–13362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.; Paolo, G.; Liu, M. Virtual-to-Real Deep Reinforcement Learning: Continuous Control of Mobile Robots for Mapless Navigation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.00420. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwata, Y.; Teo, J.; Fiore, G.; Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E.; How, J.P. Real-Time Motion Planning With Applications to Autonomous Urban Driving. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2009, 17, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Sun, C.; Yan, M. Target Search Control of AUV in Underwater Environment With Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 96549–96559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.; Kumar, N.K.S.; Sathyamoorthy, A.J.; Manocha, D. DWA-RL: Dynamically Feasible Deep Reinforcement Learning Policy for Robot Navigation among Mobile Obstacles. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 6057–6063. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Lang, L.; Yao, W.; Lu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Z. Navigating Robots in Dynamic Environment With Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 25201–25211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Sebastian, B.; Ben-Tzvi, P. A Collision Avoidance Method Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Robotics 2021, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, P.; Schön, T.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Cremers, D. Vision-Based Mobile Robotics Obstacle Avoidance With Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 14360–14366. [Google Scholar]

- Beomsoo, H.; Ravankar, A.A.; Emaru, T. Mobile Robot Navigation Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning with 2D-LiDAR Sensor Using Stochastic Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Safety for Robotics (ISR), Nagoya, Japan, 4–6 March 2021; pp. 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kaymak, Ç.; Uçar, A.; Güzeliş, C. Development of a New Robust Stable Walking Algorithm for a Humanoid Robot Using Deep Reinforcement Learning with Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. Electronics 2023, 12, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Zhang, S. Pruning Replay Buffer for Efficient Training of Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Emerg. Investig. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Niu, H.; Carrasco, J.; Arvin, F.; Yin, H.; Lennox, B. Design and Experimental Validation of Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Fast Trajectory Planning and Control for Mobile Robot in Unknown Environment. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 5778–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Chiun, J.; Zhang, M.; Sartoretti, G.A. Context-Aware Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Robotic Navigation in Unknown Area. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Robot Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 November 2023; pp. 1425–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Samsani, S.S.; Mutahira, H.; Muhammad, M.S. Memory-Based Crowd-Aware Robot Navigation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2023, 9, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Meng, Z.; Lu, W.; Tong, Z. End-to-End Autonomous Driving Decision Method Based on Improved TD3 Algorithm in Complex Scenarios. Sensors 2024, 24, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, E.E.; Mutahira, H.; Pico, N.; Muhammad, M.S. Dynamic Warning Zone and a Short-Distance Goal for Autonomous Robot Navigation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrevski, M.; Skočaj, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Map-Less Goal-Driven Robot Navigation. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 1729881421992621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-F.R.; Yusuf, S.H. Mobile Robot Navigation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Processes 2022, 10, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Wang, H.; Esfahani, M.A.; Yuan, S. Learn to Navigate Autonomously Through Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 5342–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimurs, R.; Suh, I.H.; Lee, J.H. Goal-Driven Autonomous Exploration Through Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Mao, S.; Wu, Z.; Kong, P.; Qiang, H. Improved Path Planning for Indoor Patrol Robot Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Symmetry 2022, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaar, A.A.N.; Kochuvila, S. Mobile Service Robot Path Planning Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 100083–100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Path Planning of Mobile Robot Based on Improved TD3 Algorithm in Dynamic Environment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakoon, K.; Sathyamoorthy, A.J.; Patel, U.; Manocha, D. TERP: Reliable Planning in Uneven Outdoor Environments Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 9447–9453. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; He, Z.; Cao, D.; Ma, L.; Li, K.; Jia, L.; Cui, Y. Coverage Path Planning for Kiwifruit Picking Robots Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zheng, R. Multi-Robot Path Planning for Mobile Sensing through Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2021—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10 May 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, A.; Shaikh, I.U.H.; Ali, A. Application of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Tracking Control of 3WD Omnidirectional Mobile Robot. Inf. Technol. Control 2021, 50, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Xu, G.; Feng, N.; Li, L.; Jiang, W.; Yu, L.; Xiong, X. Spatiotemporal Path Tracking via Deep Reinforcement Learning of Robot for Manufacturing Internal Logistics. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 69, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, E.; Stefanidou, A.; Chronis, C.; Dimitrakopoulos, G.; Varlamis, I. Adaptive Deep Reinforcement Learning for Efficient 3D Navigation of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 178209–178221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.C. Traffic-Cognitive Slicing for Resource-Efficient Offloading with Dual-Distillation DRL in Multi-Edge Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.04192. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.; Lin, M.; Li, D.; Lin, R.; Xiao, S. Adaptive Reward Shaping Based Reinforcement Learning for Docking Control of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 318, 120139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yin, H.; Guo, X.; Wu, J. Energy-Saving Optimization of Urban Rail Transit Timetable: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388478545_Energy-Saving_Optimization_of_Urban_Rail_Transit_Timetable_A_Deep_Reinforcement_Learning_Approach (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Khaitan, S. Exploring Reinforcement Learning Approaches for Safety Critical Environments. Master’s Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.; Long, P.; Liu, W.; Pan, J.; Yang, R.; Manocha, D. Learning Resilient Behaviors for Navigation under Uncertainty. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1910.09998. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, C.; Cai, Y.; Yan, T.; Su, B. Deep Reinforcement Learning in Autonomous Car Path Planning and Control: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.00340. [Google Scholar]

- Günster, J.; Liu, P.; Peters, J.; Tateo, D. Handling Long-Term Safety and Uncertainty in Safe Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12045. [Google Scholar]

- Aali, M. Learning-Based Safety-Critical Control Under Uncertainty with Applications to Mobile Robots. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, R.; Kwon, G. Safety Constraint-Guided Reinforcement Learning with Linear Temporal Logic. Systems 2023, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Elfwing, S.; Uchibe, E. Modular Deep Reinforcement Learning from Reward and Punishment for Robot Navigation. Neural Netw. 2021, 135, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. Robust AI Algorithms for Autonomous Vehicle Perception: Fusing Sensor Data from Vision, LiDAR, and Radar for Enhanced Safety. J. AI-Assist. Sci. Discov. 2024, 4, 118–157. [Google Scholar]

- Nissov, M.; Khattak, S.; Edlund, J.A.; Padgett, C.; Alexis, K.; Spieler, P. ROAMER: Robust Offroad Autonomy Using Multimodal State Estimation with Radar Velocity Integration. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mitta, N.R. AI-Enhanced Sensor Fusion Techniques for Autonomous Vehicle Perception: Integrating Lidar, Radar, and Camera Data with Deep Learning Models for Enhanced Object Detection, Localization, and Scene Understanding. J. Bioinform. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.-C.; Ni, Z.; Zhong, X.; Wei, M. Autonomous Robot Goal Seeking and Collision Avoidance in the Physical World: An Automated Learning and Evaluation Framework Based on the PPO Method. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Ge, Y.; Shi, G.; Wang, Z.; Yang, N.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; Jia, Z. TAIL: A Terrain-Aware Multi-Modal SLAM Dataset for Robot Locomotion in Deformable Granular Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6696–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, F. Multi-Sensor Fusion for Autonomous Resilient Perception. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Merveille, F.F.R.; Jia, B.; Xu, Z.; Fred, B. Advancements in Sensor Fusion for Underwater SLAM: A Review on Enhanced Navigation and Environmental Perception. Sensors 2024, 24, 7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, A. RDDRL: A Recurrent Deduction Deep Reinforcement Learning Model for Multimodal Vision-Robot Navigation. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 23244–23270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Deng, H.; Zhang, W.; Song, R.; Li, Y. Towards Multi-Modal Perception-Based Navigation: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Method. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4986–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.A. Big Data and Machine Learning in Autonomous Vehicle Navigation: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Appl. Cybersecur. Anal. Intell. Decis.-Mak. Syst. 2024, 14, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R.; Srinivaas, A.; Velamati, R.K. Adaptive Navigation in Collaborative Robots: A Reinforcement Learning and Sensor Fusion Approach. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.J.; Thompson, D.R.; Nguyen, J.T.; Wright, B.A. A Sensor-Fused Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Multi-Agent Decision-Making in Urban Driving Environments. Int. J. Eng. Adv. 2025, 2, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Raettig, T.N. Heterogeneous Collaborative Robotics: Multi-Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environments. Master’s Thesis, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, D.; Shen, Y.; Yang, X. Dual Experience Replay-Based TD3 for Single Intersection Signal Control. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 15161–15182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Reinforcement Learning and Swarm Intelligence for Cooperative Aerial Navigation and Payload Transportation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Koradiya, G. Reinforcement Learning Based Planning and Control for Robotic Source Seeking Inspired by Fruit Flies. Master’s Thesis, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden Domingo, À. Training Cooperative and Competitive Multi-Agent Systems. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; He, Z.; Song, C.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, H. Multi-Robot Social-Aware Cooperative Planning in Pedestrian Environments Using Attention-Based Actor-Critic. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClusky, B. Dynamic Graph Communication for Decentralised Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2501.00165. [Google Scholar]

- Egorov, V.; Shpilman, A. Scalable Multi-Agent Model-Based Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.15023. [Google Scholar]

- Gronauer, S.; Diepold, K. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 895–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Towards Efficient Cooperation Within Learning Agents. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. Cooperative and Competitive Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and High-Performance Computing (AIAHPC 2022), Zhuhai, China, 25–27 February 2022; Volume 12348, pp. 599–613. [Google Scholar]

- Nekoei, H.; Badrinaaraayanan, A.; Sinha, A.; Amini, M.; Rajendran, J.; Mahajan, A.; Chandar, S. Dealing with Non-Stationarity in Decentralized Cooperative Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning via Multi-Timescale Learning. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Lifelong Learning Agents, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20 November 2023; pp. 376–398. [Google Scholar]

- Oroojlooy, A.; Hajinezhad, D. A Review of Cooperative Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 13677–13722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra Gomez, A. Motion Planning in Dynamic Environments with Learned Scalable Policies. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Delft, Delft, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperative Localization of UAVs in Multi-Robot Systems Using Deep Learning-Based Detection|AIAA SciTech Forum. Available online: https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/abs/10.2514/6.2025-1537 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Jeong, E.; Gwak, J.; Kim, T.; Kang, D.-O. Distributed Deep Learning for Real-World Implicit Mapping in Multi-Robot Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 24th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 29 October–1 November 2024; pp. 1619–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Robust AI Based Perception and Guidance for Autonomous Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Muratore, F.; Ramos, F.; Turk, G.; Yu, W.; Gienger, M.; Peters, J. Robot Learning from Randomized Simulations: A Review. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 9, 799893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Belkhale, S.; Kahn, G.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Generalization through Simulation: Integrating Simulated and Real Data into Deep Reinforcement Learning for Vision-Based Autonomous Flight. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yavas, M.U.; Kumbasar, T.; Ure, N.K. A Real-World Reinforcement Learning Framework for Safe and Human-like Tactical Decision-Making. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11773–11784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, P.L.F. Domain Adaptation in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Landing Using Reinforcement Learning. Master’s Thesis, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, Z.; Lv, C. Human-Guided Reinforcement Learning with Sim-to-Real Transfer for Autonomous Navigation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 14745–14759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Baek, J.; Jeon, S.; Han, S. Bridging the Simulation-to-Real Gap of Depth Images for Deep Reinforcement Learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 253, 124310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Queralta, J.P.; Westerlund, T. Sim-to-Real Transfer in Deep Reinforcement Learning for Robotics: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Canberra, ACT, Australia, 1–4 December 2020; pp. 737–744. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwurah, N.; Adebayo, A.S.; Ajayi, O.O. Sim-to-Real Transfer in Robotics: Addressing the Gap between Simulation and Real-World Performance. JFMR 2024, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratore, F. Randomizing physics simulations for robot learning. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Josifovski, J.; Malmir, M.; Klarmann, N.; Žagar, B.L.; Navarro-Guerrero, N.; Knoll, A. Analysis of Randomization Effects on Sim2Real Transfer in Reinforcement Learning for Robotic Manipulation Tasks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.06282. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Zeng, P.; Wan, G.; He, Y.; Dong, X. Kalman Filter-Based One-Shot Sim-to-Real Transfer Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, L. Neural Fidelity Calibration for Informative Sim-to-Real Adaptation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.08604. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, H.; Juan, R.; Gomez, R.; Nakamura, K.; Li, G. Transferring Policy of Deep Reinforcement Learning from Simulation to Reality for Robotics. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkarunai Arasu Malaiyappan, J.; Mani Krishna Sistla, S.; Jeyaraman, J. Advancements in Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for Autonomous Systems. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 1941–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolc, H.; Desnos, K.; Kryjak, T. Tangled Program Graphs as an Alternative to DRL-Based Control Algorithms for UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2024 Signal Processing: Algorithms, Architectures, Arrangements, and Applications (SPA), Poznan, Poland, 25–27 September 2024; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S. From AI Safety Gridworlds to Reliable Safety Unit Tests for Deep Reinforcement Learning in Computer Systems. Master’s Thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg, Magdeburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, H. On the Interpretability of Reinforcement Learning. Available online: https://www.surrey.ac.uk/events/20240626-interpretability-reinforcement-learning (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. Multiagent Reinforcement Learning: Methods, Trustworthiness, Applications in Intelligent Vehicles, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Chronological Overview and Methods. AI 2025, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, G.; Hovy, E. Reinforcement Learning Enhanced LLMs: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2412.10400. [Google Scholar]

- Hickling, T.; Zenati, A.; Aouf, N.; Spencer, P. Explainability in Deep Reinforcement Learning, a Review into Current Methods and Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2207.01911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, M. Towards Mutation Testing of Reinforcement Learning Systems. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 131, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, S.A.; Muzahid, A.J.M.; Azmi, Z.R.M.; Hoque, M.I.; Kowsher, M. A Review on Job Scheduling Technique in Cloud Computing and Priority Rule Based Intelligent Framework. J. King Saud. Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 2309–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Humphreys, J.; Peng, T.; Zhou, C. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Bipedal Locomotion: A Brief Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.17070. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Cheng, G.; Kong, L.; Dong, L.; Sun, C. Robust Navigation with Cross-Modal Fusion and Knowledge Transfer. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.13266. [Google Scholar]

- Kalenberg, K.; Müller, H.; Polonelli, T.; Schiaffino, A.; Niculescu, V.; Cioflan, C.; Magno, M.; Benini, L. Stargate: Multimodal Sensor Fusion for Autonomous Navigation on Miniaturized UAVs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 21372–21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Lee, V.C.; Liang, X.; Chang, X. Deep Learning for Embodied Vision Navigation: A Survey. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.04097. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Zeng, L.; Li, G.; Ju, Z. Learning for a Robot: Deep Reinforcement Learning, Imitation Learning, Transfer Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| [21] | This study categorizes path planning methodologies into four main types: learning-based, space-based, time-based, and environment-based approaches. It introduces a novel taxonomy that encompasses the transition from classical to state-of-the-art methods for path planning in dynamic environments. |

| [22] | This systematic review explores the application of DRL in mobile robot navigation within hazardous environments. It classifies navigation approaches into three categories—autonomous-based, SLAM-based, and planning-based navigation—and analyzes their respective strengths and weaknesses. |

| [23] | This review examines the applications, advantages, and limitations of deep learning in robotic systems, providing an analysis based on contemporary research. |

| [4] | This paper reviews AI-enhanced navigation strategies for mobile robots, highlighting the distinctions among different approaches. |

| [24] | This study systematically introduces and summarizes existing DRL-based exploration methods and discusses their potential applications in robot attitude control tasks. |

| [25] | This paper provides an overview of fundamental concepts in deep reinforcement learning, including value functions and policy gradient algorithms, and discusses their applications in mobile robot path planning. |

| [26] | This review investigates DRL methods and DRL-based navigation frameworks, systematically comparing and analyzing the similarities and differences in four typical application scenarios. |

| Ref. | Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Suited for |

| [41,42,43] | Classical Control (Dijkstra, A*, RRT, DWA) | Deterministic, mathematically well-founded, efficient in structured/static environments | Poor adaptability in dynamic settings, requires frequent re-planning | Structured and static environments with predefined obstacles |

| [13] | Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) | Adaptive, real-time decision-making, good generalization in non-stationary settings | High training complexity, requires extensive computational resources and well-designed reward functions | Dynamic and unpredictable environments requiring flexible navigation |

| [44,45] | Hybrid Learning (Neuro-SLAM, Imitation Learning) | Improves perception and localization (Neuro-SLAM), faster learning from expert demonstrations (imitation learning) | Limited adaptability due to reliance on pre-trained models (Neuro-SLAM), requires high-quality expert data (imitation learning) | Enhancing classical navigation methods with learning-based adaptations |

| [46,47] | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) | Enables cooperation, adaptive to teammates/adversaries, efficient for multi-robot tasks | Communication constraints, higher computational complexity, policy convergence challenges | Collaborative multi-robot navigation and swarm intelligence |

| Thematic Group | Included Sections | Focus Area |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptability and Perception | Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 | Real-time policy adaptation and multimodal sensory integration |

| Collaboration and Transfer | Section 4.3, Section 4.4 and Section 4.5 | Sim-to-real knowledge transfer and multi-robot coordination |

| Safety and Deployment Robustness | Section 4.4, Section 4.5 and Section 4.6 | Interpretability, algorithmic safety, and cross-domain generalization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Wan Hasan, W.Z.; Harun Ramli, H.R.; Norsahperi, N.M.H.; Mohd Kassim, M.S.; Yao, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning of Mobile Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environment: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25113394

Zhu Y, Wan Hasan WZ, Harun Ramli HR, Norsahperi NMH, Mohd Kassim MS, Yao Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning of Mobile Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environment: A Review. Sensors. 2025; 25(11):3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25113394

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yingjie, Wan Zuha Wan Hasan, Hafiz Rashidi Harun Ramli, Nor Mohd Haziq Norsahperi, Muhamad Saufi Mohd Kassim, and Yiduo Yao. 2025. "Deep Reinforcement Learning of Mobile Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environment: A Review" Sensors 25, no. 11: 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25113394

APA StyleZhu, Y., Wan Hasan, W. Z., Harun Ramli, H. R., Norsahperi, N. M. H., Mohd Kassim, M. S., & Yao, Y. (2025). Deep Reinforcement Learning of Mobile Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environment: A Review. Sensors, 25(11), 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25113394