Evaluation of the Margin of Stability during Gait Initiation in Young Healthy Adults, Elderly Healthy Adults and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Force Plate and Markerless Motion Capture Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

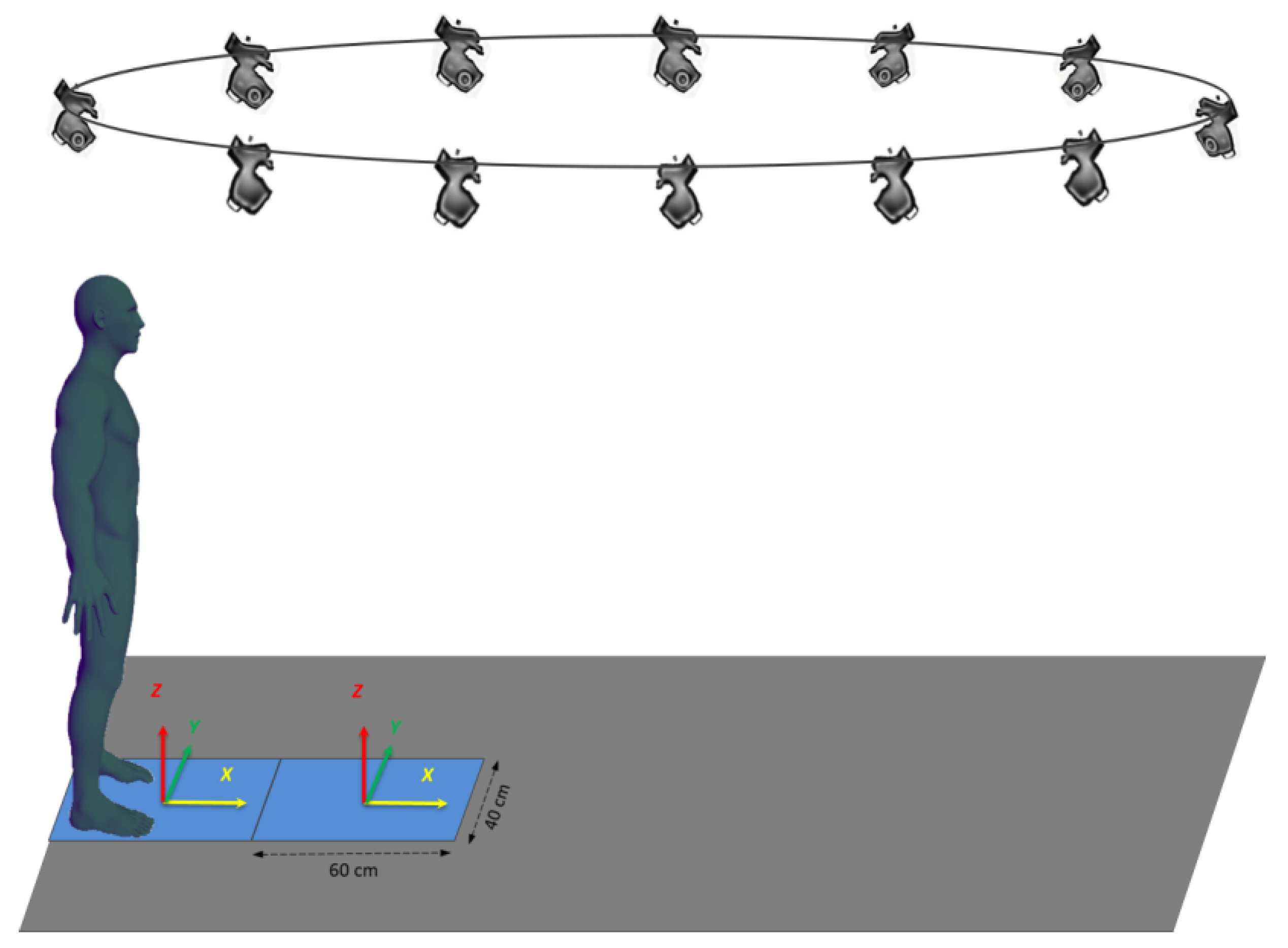

2.2. Experimental Set-Up, Tasks and Conditions

2.3. Raw Data Processing

2.3.1. Force Plate System

2.3.2. Markerless Motion Capture System

2.4. Margin of Stability

2.5. Experimental Variables

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Biomechanical Traces

3.2. Bland–Altman Analysis

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Bayes Factor 01

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brenière, Y.; Cuong Do, M.; Bouisset, S. Are Dynamic Phenomena Prior to Stepping Essential to Walking? J. Mot. Behav. 1987, 19, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastan, N.; Westby, G.W.M.; Yelnik, J.; Bardinet, E.; Do, M.C.; Agid, Y.; Welter, M.L. Effects of Nigral Stimulation on Locomotion and Postural Stability in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Brain 2009, 132, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastan, N.; Do, M.C.; Bonneville, F.; Torny, F.; Bloch, F.; Westby, G.W.M.; Dormont, D.; Agid, Y.; Welter, M.-L. Gait and Balance Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease: Impaired Active Braking of the Fall of Centre of Gravity. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demain, A.; Westby, G.W.M.; Fernandez-Vidal, S.; Karachi, C.; Bonneville, F.; Do, M.C.; Delmaire, C.; Dormont, D.; Bardinet, E.; Agid, Y.; et al. High-Level Gait and Balance Disorders in the Elderly: A Midbrain Disease? J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiou, E.; Caderby, T.; Delafontaine, A.; Fourcade, P.; Honeine, J.-L. Balance Control during Gait Initiation: State-of-the-Art and Research Perspectives. World J. Orthop. 2017, 8, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delval, A.; Tard, C.; Defebvre, L. Why We Should Study Gait Initiation in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurophysiol. Clin./Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 44, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hof, A.L.; Gazendam, M.G.J.; Sinke, W.E. The Condition for Dynamic Stability. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caderby, T.; Yiou, E.; Peyrot, N.; Begon, M.; Dalleau, G. Influence of Gait Speed on the Control of Mediolateral Dynamic Stability during Gait Initiation. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delafontaine, A.; Fourcade, P.; Honeine, J.L.; Ditcharles, S.; Yiou, E. Postural Adaptations to Unilateral Knee Joint Hypomobility Induced by Orthosis Wear during Gait Initiation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialleron, T.; Delafontaine, A.; Millerioux, I.; Memari, S.; Fourcade, P.; Yiou, E. Acute Effects of Short-Term Stretching of the Triceps Surae on Ankle Mobility and Gait Initiation in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Biomech. 2021, 89, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, B.E.; Mcllroy, W.E. The Control of Foot Placement during Compensatory Stepping Reactions: Does Speed of Response Take Precedence over Stability? IEEE Trans. Rehab. Eng. 1999, 7, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiou, E.; Teyssèdre, C.; Artico, R.; Fourcade, P. Comparison of Base of Support Size during Gait Initiation Using Force-Plate and Motion-Capture System: A Bland and Altman Analysis. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 4168–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonet, A.; Delafontaine, A.; Fourcade, P.; Yiou, E. Vertical Center-of-Mass Braking and Motor Performance during Gait Initiation in Young Healthy Adults, Elderly Healthy Adults, and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Force-Plate and Markerless Motion Capture Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.; Alcock, L.; McArdle, R.; Rehman, R.; Del Din, S.; Mazzà, C.; Yarnall, A.; Rochester, L. The Role of Movement Analysis in Diagnosing and Monitoring Neurodegenerative Conditions: Insights from Gait and Postural Control. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lach, J.; Lo, B.; Yang, G.-Z. Toward Pervasive Gait Analysis with Wearable Sensors: A Systematic Review. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2016, 20, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiari, L.; Della Croce, U.; Leardini, A.; Cappozzo, A. Human Movement Analysis Using Stereophotogrammetry. Part 2: Instrumental Errors. Gait Posture 2005, 21, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, G.E.; Hebert, D.A.; Gannotti, M.E. Assessment of the Kinematic Variability among 12 Motion Analysis Laboratories. Gait Posture 2009, 29, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-García, V.; Corral-Bergantiños, Y.; Espinosa, N.; Jácome, M.A.; García-Sancho, C.; Cudeiro, J.; Arias, P. Spatiotemporal Gait Patterns During Overt and Covert Evaluation in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Healthy Subjects: Is There a Hawthorne Effect? J. Appl. Biomech. 2015, 31, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, M.W. Clinical Gait Analysis: A Review. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1996, 15, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyer, S.L.; Evans, M.; Cosker, D.P.; Salo, A.I.T. A Review of the Evolution of Vision-Based Motion Analysis and the Integration of Advanced Computer Vision Methods towards Developing a Markerless System. Sport. Med.-Open 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, N.J. Using Deep Neural Networks for Kinematic Analysis: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Biomech. 2021, 123, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazan, J.F.; Phillips, W.T.; Seethapathi, N.; Hullfish, T.J.; Baxter, J.R. Moving Outside the Lab: Markerless Motion Capture Accurately Quantifies Sagittal Plane Kinematics during the Vertical Jump. J. Biomech. 2021, 125, 110547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Sigurðsson, H.B.; Seymore, K.D.; Arhos, E.K.; Buchanan, T.S.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Grävare Silbernagel, K. Markerless Motion Capture: What Clinician-Scientists Need to Know Right Now. JSAMS Plus 2022, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.; Selbie, W.S.; Deluzio, K.J. Inter-Session Repeatability of Markerless Motion Capture Gait Kinematics. J. Biomech. 2021, 121, 110422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.K.; Davis, E.M.; Selbie, W.S.; Deluzio, K.J. Concurrent Assessment of Gait Kinematics Using Marker-Based and Markerless Motion Capture. J. Biomech. 2021, 127, 110665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.K.; Strutzenberger, G.; Brown, M.; Selbie, W.S.; DePaul, V.; Scott, S.H.; Deluzio, K.J. Assessment of Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters Using a Deep Learning Algorithm-Based Markerless Motion Capture System. J. Biomech. 2021, 122, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, V.T.; Outerleys, J.B.; Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.K.; Deluzio, K.J. Clothing Condition Does Not Affect Meaningful Clinical Interpretation in Markerless Motion Capture. J. Biomech. 2022, 141, 111182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A.; Mamidanna, P.; Cury, K.M.; Abe, T.; Murthy, V.N.; Mathis, M.W.; Bethge, M. DeepLabCut: Markerless Pose Estimation of User-Defined Body Parts with Deep Learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hullfish, T.J.; Silva, R.S.; Silbernagel, K.G.; Baxter, J.R. Markerless Motion Capture Estimates of Lower Extremity Kinematics and Kinetics Are Comparable to Marker-Based across 8 Movements. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauby, C.E.; Kuo, A.D. Active Control of Lateral Balance in Human Walking. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, I.N.; Day, B.L. Control of Frontal Plane Body Motion in Human Stepping. Exp. Brain Res. 1997, 115, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettel, J.L.; McIlroy, W.E.; Maki, B.E. Environmental Constraints on Foot Trajectory Reveal the Capacity for Modulation of Anticipatory Postural Adjustments during Rapid Triggered Stepping Reactions. Exp. Brain Res. 2002, 146, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-39818-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys, H. Theory of Probability, 3rd ed.; Oxford Classic Texts in the Physical Sciences; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-19-850368-2. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery, A.E. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Sociol. Methodol. 1995, 25, 111–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. A Practical Solution to the Pervasive Problems Ofp Values. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2007, 14, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotton, J.; Fitzgibbon, A.; Cook, M.; Sharp, T.; Finocchio, M.; Moore, R.; Kipman, A.; Blake, A. Real-Time Human Pose Recognition in Parts from Single Depth Images. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2011, Providence, RI, USA, 20–25 June 2011; pp. 1297–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Yang, R.; Gall, J. A Survey on Human Motion Analysis from Depth Data; Grzegorzek, M., Theobalt, C., Koch, R., Kolb, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8200, pp. 149–187. [Google Scholar]

- Riazati, S.; McGuirk, T.E.; Perry, E.S.; Sihanath, W.B.; Patten, C. Absolute Reliability of Gait Parameters Acquired with Markerless Motion Capture in Living Domains. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 867474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Age (Years) | Gender (Female/Male) | Body Mass (kg) | Height (m) | BMI (kg/m2) | Shoe Size (EU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD (n = 12) | 68.4 ± 5.1 | 1/10 | 70.5 ± 11.8 | 1.70 ± 0.07 | 24.5 ± 3.6 | 41.3 ± 1.5 |

| YH (n = 10) | 24.7 ± 0.7 | 4/5 | 70.2 ± 13.5 | 1.70 ± 0.12 | 24.7 ± 0.7 | 40.3 ± 3.7 |

| EH (n = 11) | 66.5 ± 3.6 | 8/3 | 63.9 ± 10.1 | 1.65 ± 0.06 | 23.4 ± 3.4 | 39.3 ± 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simonet, A.; Fourcade, P.; Loete, F.; Delafontaine, A.; Yiou, E. Evaluation of the Margin of Stability during Gait Initiation in Young Healthy Adults, Elderly Healthy Adults and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Force Plate and Markerless Motion Capture Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113322

Simonet A, Fourcade P, Loete F, Delafontaine A, Yiou E. Evaluation of the Margin of Stability during Gait Initiation in Young Healthy Adults, Elderly Healthy Adults and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Force Plate and Markerless Motion Capture Systems. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113322

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimonet, Arnaud, Paul Fourcade, Florent Loete, Arnaud Delafontaine, and Eric Yiou. 2024. "Evaluation of the Margin of Stability during Gait Initiation in Young Healthy Adults, Elderly Healthy Adults and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Force Plate and Markerless Motion Capture Systems" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113322

APA StyleSimonet, A., Fourcade, P., Loete, F., Delafontaine, A., & Yiou, E. (2024). Evaluation of the Margin of Stability during Gait Initiation in Young Healthy Adults, Elderly Healthy Adults and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Force Plate and Markerless Motion Capture Systems. Sensors, 24(11), 3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113322