Development and Characterization of Novel Conductive Sensing Fibers for In Vivo Nerve Stimulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Electrically Conductive Organic Fibers (ECFs)

2.2. Electrical Impedance

2.3. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity

2.4. Animal Model

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fiber Characterization

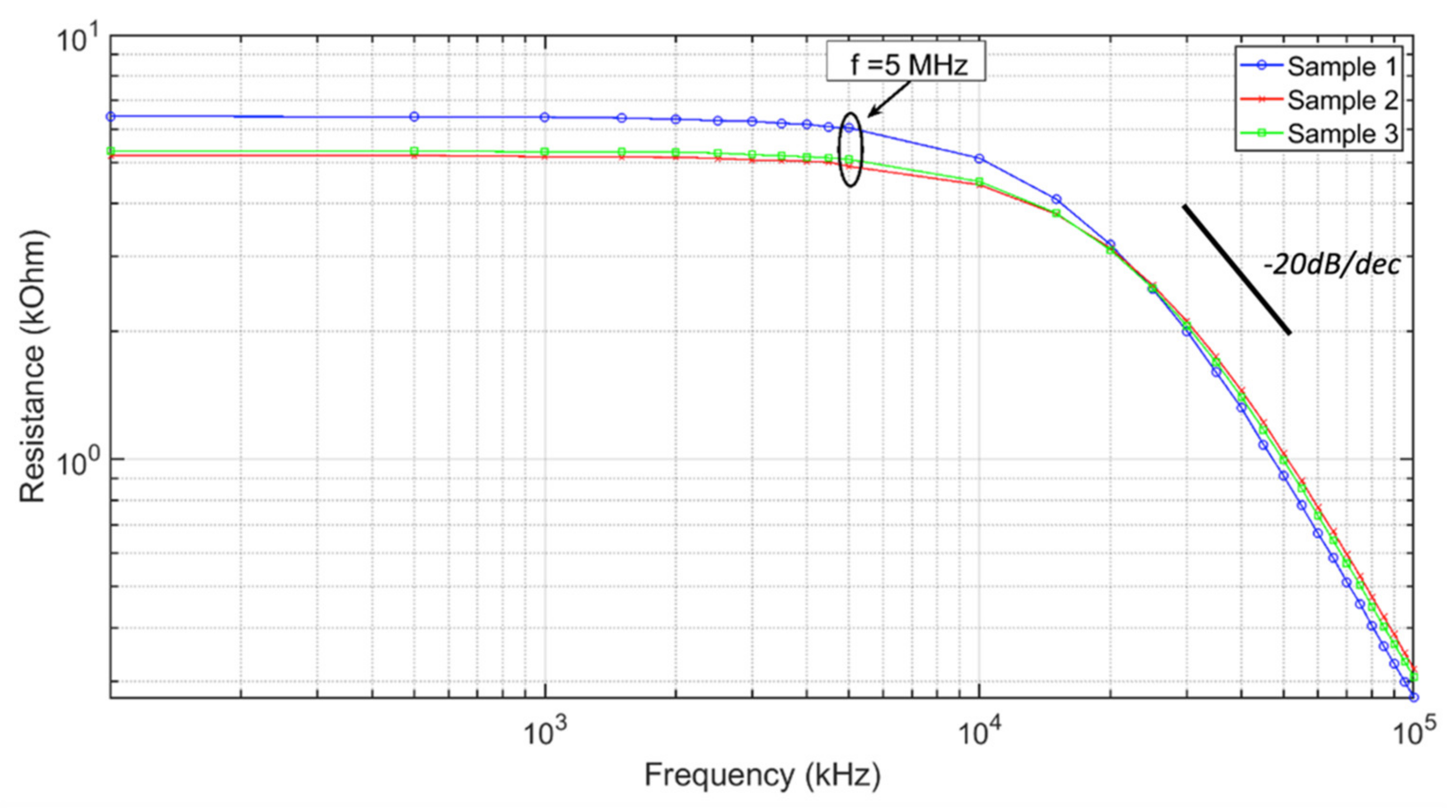

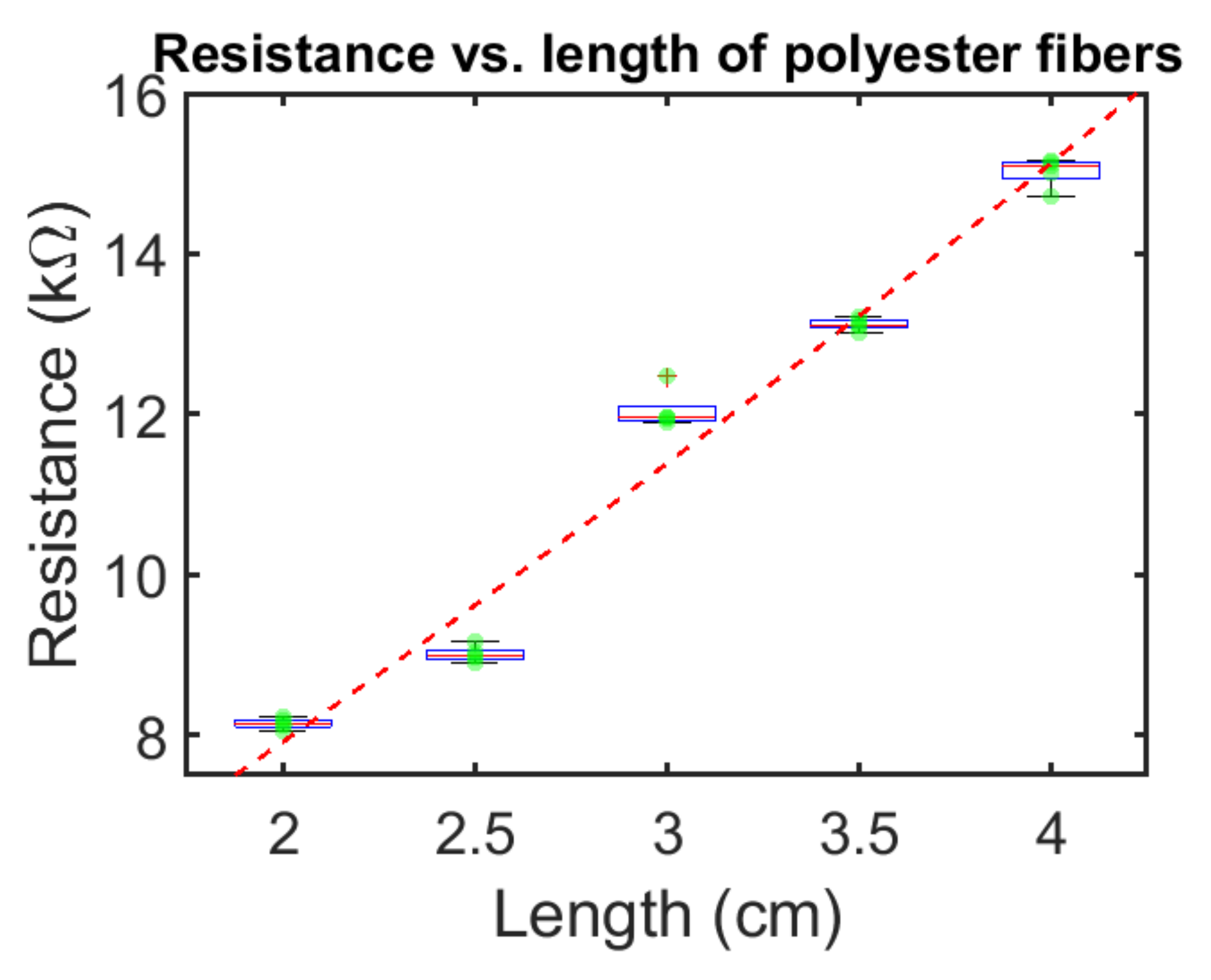

3.2. Electrical Measurements of Polyester ECFs

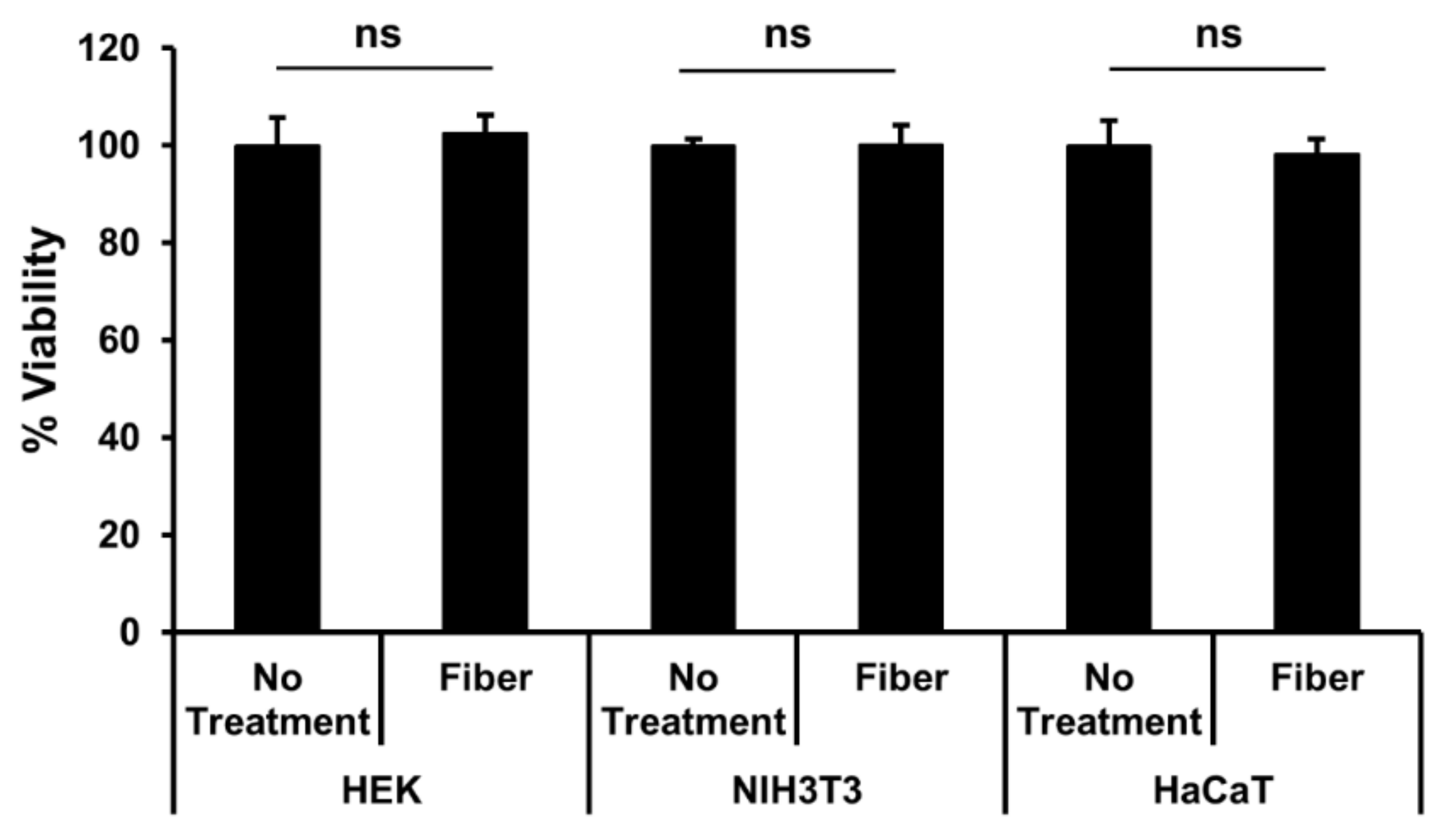

3.3. Fiber Cytotoxicity Testing

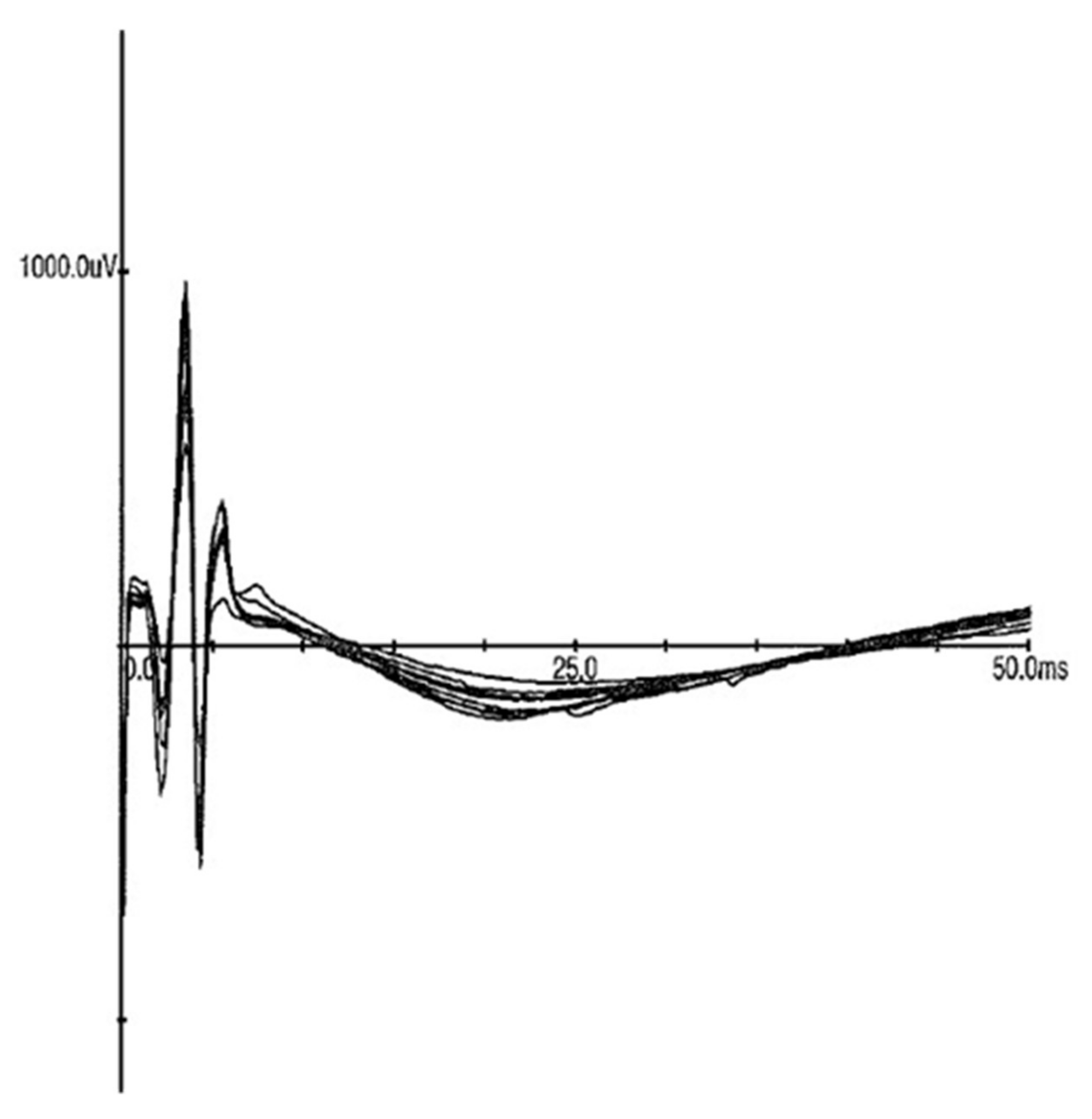

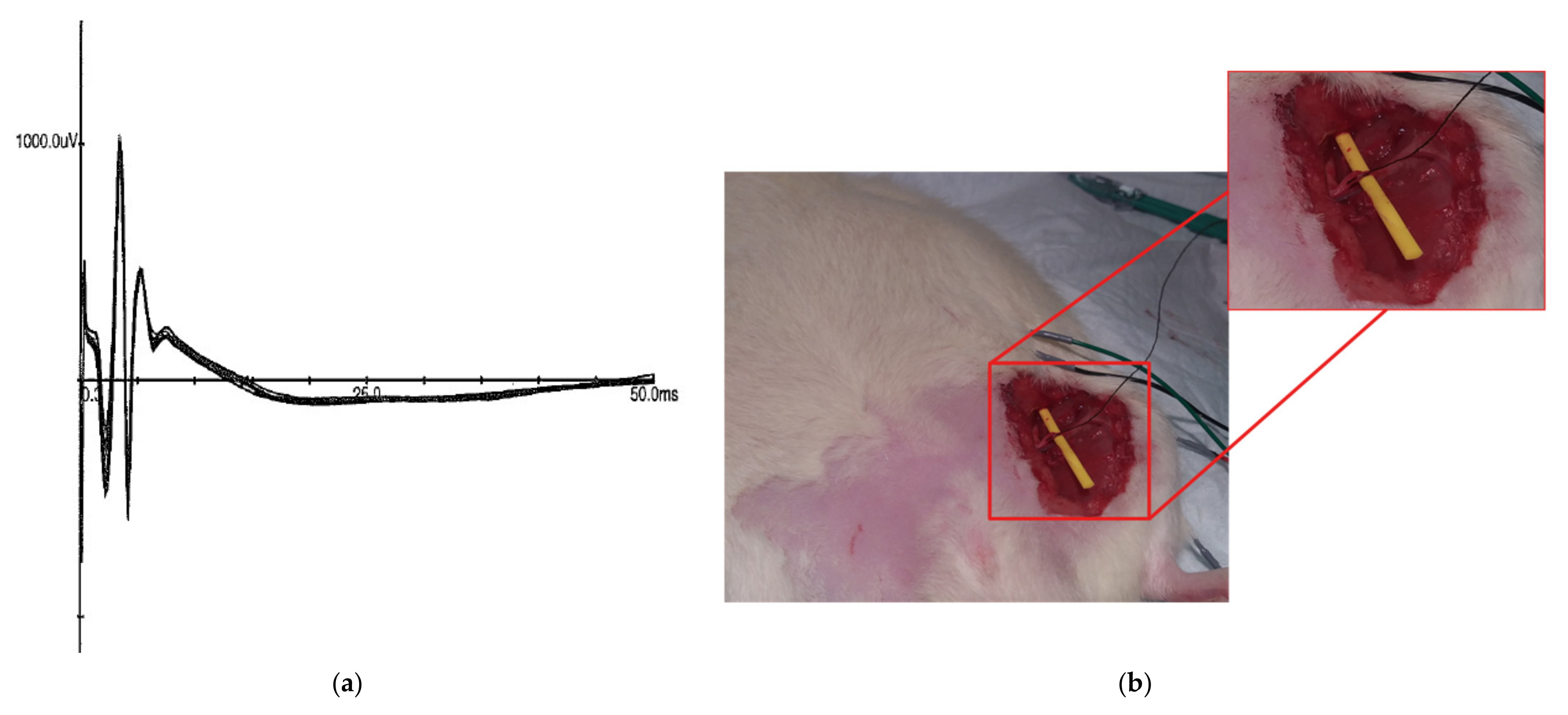

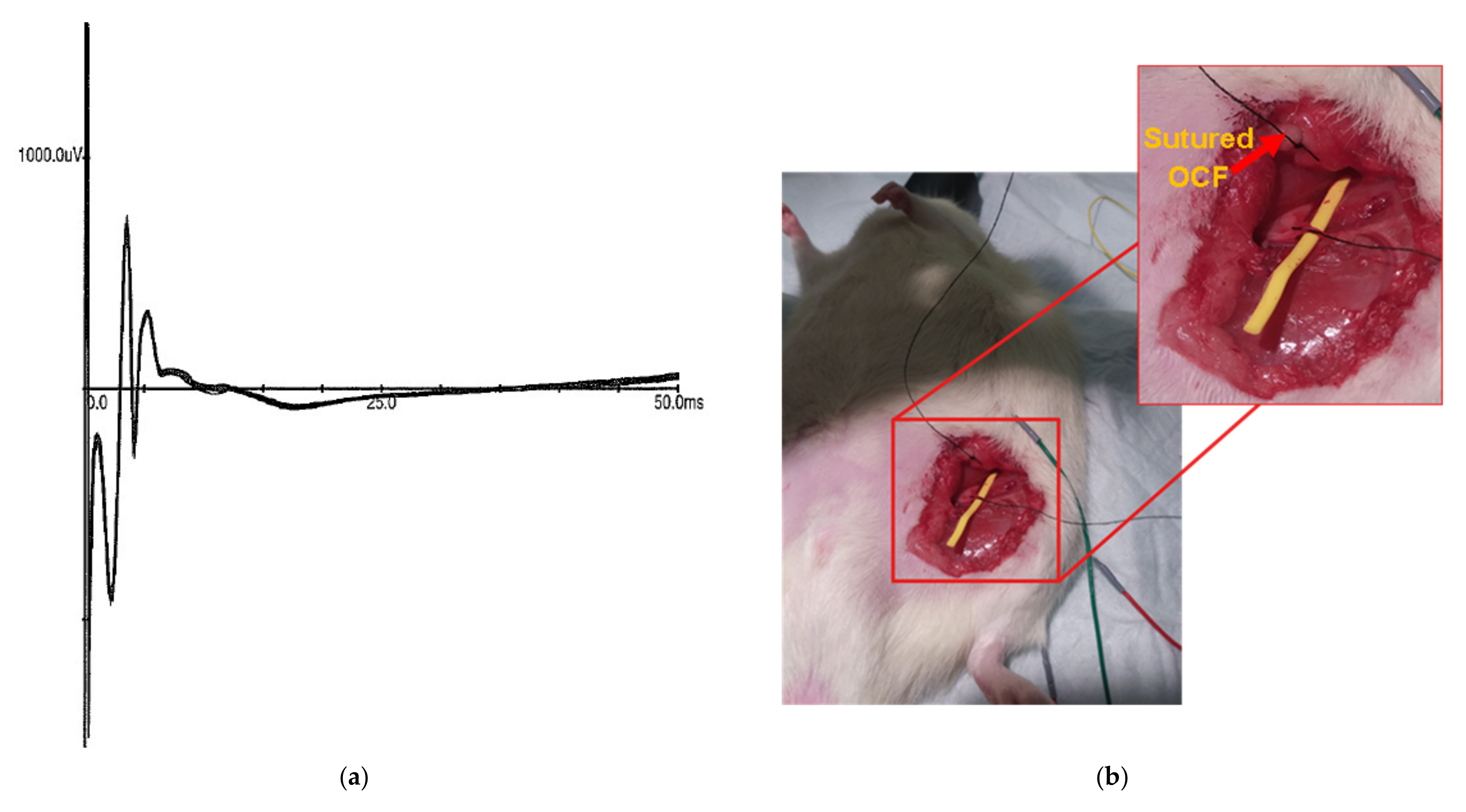

3.4. In Vivo Stimulation

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, S.; Man, W.D.; Gao, W.; Higginson, I.J.; Wilcock, A.; Maddocks, M. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for muscle weakness in adults with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, CD009419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.J.; Ravikumar, R.; Gaweesh, A.S.; Moore, H.M.; Lifsitz, A.D.; Lane, T.R.; Shalhoub, J.; Babber, A.; Davies, A.H. A Review of the Evidence to Support Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in the Prevention and Management of Venous Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 906, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrette, K.; Levin, J.; Miles, D.; Kennedy, D.J. The Value of Electrodiagnostic Studies in Predicting Treatment Outcomes for Patients with Spine Pathologies. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 29, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, I.M.; Rad, N. Electrodiagnostic Testing for the Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 29, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, D.R.; Bikson, M.; Jefferys, J.G. Electrical stimulation of excitable tissue: Design of efficacious and safe protocols. J. Neurosci. Methods 2005, 141, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, B.; Raghava, N.S. Fabrication Techniques for Carbon Nanotubes Based ECG Electrodes: A Review. IETE J. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palza, H.; Zapata, P.; Angulo-Pineda, C. Electroactive Smart Polymers for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2019, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, X.; Kang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Peng, B.; Jiang, H. Recent advances in thread-based microfluidics for diagnostic applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 132, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Remien, P.; Guballa, C.; Binder, A.; Binder, S.; Schattschneider, J.; Herzog, J.; Volkmann, J.; Deuschl, G.; Wasner, G.; et al. Effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation and levodopa on the autonomic nervous system in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, T.; Fang, H.; Hong, Z.; Sugiyama, K.; Nozaki, T.; Namba, H. Peripheral stimulation in treating Parkinson’s disease: Is it a realistic idea or a romantic whimsicality? Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2012, 1, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampusch, S.; Kaniusas, E.; Szeles, J.C. Modulation of Muscle Tone and Sympathovagal Balance in Cervical Dystonia Using Percutaneous Stimulation of the Auricular Vagus Nerve. Artif. Organs 2015, 39, E202–E212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M.D.; Alterman, R.L. Brain Stimulation for Torsion Dystonia. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalah, M.A.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Ayache, S.S. Non-invasive Central and Peripheral Stimulation: New Hope for Essential Tremor? Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsi-Zuelli, F.; Brognara, F.; Quirino, G.; Hiroki, C.H.; Fais, R.S.; Del-Ben, C.M.; Ulloa, L.; Salgado, H.C.; Kanashiro, A.; Loureiro, C.M. Neuroimmune Interactions in Schizophrenia: Focus on Vagus Nerve Stimulation and Activation of the Alpha-7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, K.V. Peripheral nerve stimulation for neuropathic pain. Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, M.A.; Antony, A.; Esposito, M.; Deer, T.; Levy, R. The Evolution of Neuromodulation in the Treatment of Chronic Pain: Forward-Looking Perspectives. Pain Med. 2019, 20, S58–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzosko, Z.; Mierau, S.B.; Paulsen, O. Neuromodulation of Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity: Past, Present, and Future. Neuron 2019, 103, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greatbatch, W. Metal electrodes in bioengineering. Crit. Rev. Bioeng. 1981, 5, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.H.; Lee, P.B.; Son, H.M.; Choi, J.B.; Moon, J.Y. Spontaneous lead breakage in implanted spinal cord stimulation systems. Korean J. Pain 2010, 23, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, D. Spinal cord stimulation: The clinical application of new technology. Anesthesiol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 375691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Campbell, A.; Wu, C. Chronically Implanted Intracranial Electrodes: Tissue Reaction and Electrical Changes. Micromachines 2018, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarowski, D.H.; Andersen, M.D.; Retterer, S.; Spence, A.J.; Isaacson, M.; Craighead, H.G.; Turner, J.N.; Shain, W. Brain responses to micro-machined silicon devices. Brain Res. 2003, 983, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, R.W.; Humphrey, D.R. Long-term gliosis around chronically implanted platinum electrodes in the Rhesus macaque motor cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 406, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.; Samikkannu, M.; Mohammed, F.; Dietrich, W.D.; Rajguru, S.M.; Prasad, A. Blood brain barrier (BBB)-disruption in intracortical silicon microelectrode implants. Biomaterials 2018, 164, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupte, A.A.; Shrivastava, D.; Spaniol, M.A.; Abosch, A. MRI-related heating near deep brain stimulation electrodes: More data are needed. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 2011, 89, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwassif, M.M.; Kong, Q.; Vazquez, M.; Bikson, M. Bio-heat transfer model of deep brain stimulation-induced temperature changes. J. Neural Eng. 2006, 3, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwassif, M.M.; Datta, A.; Rahman, A.; Bikson, M. Temperature control at DBS electrodes using a heat sink: Experimentally validated FEM model of DBS lead architecture. J. Neural Eng. 2012, 9, 046009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.T.; Pohlmeyer, E.; Gather, M.C.; Kemere, C.; Kitching, J.E.; Malliaras, G.G.; Marblestone, A.; Shepard, K.L.; Stieglitz, T.; Xie, C. Developing Next-generation Brain Sensing Technologies—A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 10163–10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Fu, X.; Liew, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Li, Q.; Stanley, G.B.; et al. Soft and MRI Compatible Neural Electrodes from Carbon Nanotube Fibers. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.N.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, Y.J.; Heo, M.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, D.; Do, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kwon, I.K. Flexible and Highly Biocompatible Nanofiber-Based Electrodes for Neural Surface Interfacing. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 2961–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, Z.; Mao, F.; Yang, C.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J.; Zuo, H.; Fan, R. Flexible Polyimide Nanocomposites with dc Bias Induced Excellent Dielectric Tunability and Unique Nonpercolative Negative-k toward Intrinsic Metamaterials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26713–26722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Zhang, H.; Ma, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, R.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Shao, Q.; et al. Trace electrosprayed nanopolystyrene facilitated dispersion of multiwalled carbon nanotubes: Simultaneously strengthening and toughening epoxy. Carbon 2019, 142, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivnay, J.; Wang, H.; Fenno, L.; Deisseroth, K.; Malliaras, G.G. Next-generation probes, particles, and proteins for neural interfacing. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, 1601649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.-r.; Kim, S.-M.; Ryu, R.-H.; Kim, S.-P.; Sohn, J.-w. Implantable Neural Probes for Brain-Machine Interfaces? Current Developments and Future Prospects. Exp. Neurobiol. 2018, 27, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.-H.; Won, S.M.; Orsborn, A.L.; Yu, K.J.; Trumpis, M.; Bent, B.; Wang, C.; Xue, Y.; Min, S.; Woods, V.; et al. Development of a neural interface for high-definition, long-term recording in rodents and nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, aay4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregueta-Robles, U.A.; Woolley, A.J.; Poole-Warren, L.A.; Lovell, N.H.; Green, R.A. Organic electrode coatings for next-generation neural interfaces. Front. Neuroeng. 2014, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adewole, D.O.; Serruya, M.D.; Wolf, J.A.; Cullen, D.K. Bioactive Neuroelectronic Interfaces. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai, T.D.Y.; Langhals, N.B.; Patel, P.R.; Deng, X.; Zhang, H.; Smith, K.L.; Lahann, J.; Kotov, N.A.; Kipke, D.R. Ultrasmall implantable composite microelectrodes with bioactive surfaces for chronic neural interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guitchounts, G.; Markowitz, J.E.; Liberti, W.A.; Gardner, T.J. A carbon-fiber electrode array for long-term neural recording. J. Neural Eng. 2013, 10, 046016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kong, C.; Chang, J.W.; Jun, S.B. Carbon-Fiber Based Microelectrode Array Embedded with a Biodegradable Silk Support for In Vivo Neural Recording. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2019, 34, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, S.D.; Koenen, S.; Jakobi, J.; Heissler, H.E.; Alam, M.; Schwabe, K.; Barcikowski, S.; Krauss, J.K. Electrophoretic deposition of ligand-free platinum nanoparticles on neural electrodes affects their impedance in vitro and in vivo with no negative effect on reactive gliosis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, S.; Richter, B.; Mace, Z.S.; Sclabassi, R.J.; Cheng, B.; Whiting, D.M.; Averick, S.; Nelson, T.L. Organic Conductive Fibers as Nonmetallic Electrodes and Neural Interconnects. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 7866–7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.Q.; Cheng, C.; Sangasoongsong, A.; Wongdhamma, W.; Bukkapatnam, S.T.S. Wireless Wearable Multisensory Suite and Real-Time Prediction of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Episodes. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2013, 1, 2700109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.Q.; Chandra, V.; Afrin, K.; Srivatsa, S.; Bukkapatnam, S. A Dynamic Systems Approach for Detecting and Localizing of Infarct-Related Artery in Acute Myocardial Infarction Using Compressed Paper-Based Electrocardiogram (ECG). Sensors 2020, 20, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.Q.; Bukkapatnam, S.T.S. Nonlinear Dynamics Forecasting of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Onsets. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ECF Sample | Resistance (DC) | Resistance (at 1 MHz) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.40 kohms | 6.48 kohms |

| 2 | 5.16 kohms | 5.19 kohms |

| 3 | 5.35 kohms | 5.35 kohms |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richter, B.; Mace, Z.; Hays, M.E.; Adhikari, S.; Pham, H.Q.; Sclabassi, R.J.; Kolber, B.; Yerneni, S.S.; Campbell, P.; Cheng, B.; et al. Development and Characterization of Novel Conductive Sensing Fibers for In Vivo Nerve Stimulation. Sensors 2021, 21, 7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21227581

Richter B, Mace Z, Hays ME, Adhikari S, Pham HQ, Sclabassi RJ, Kolber B, Yerneni SS, Campbell P, Cheng B, et al. Development and Characterization of Novel Conductive Sensing Fibers for In Vivo Nerve Stimulation. Sensors. 2021; 21(22):7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21227581

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichter, Bertram, Zachary Mace, Megan E. Hays, Santosh Adhikari, Huy Q. Pham, Robert J. Sclabassi, Benedict Kolber, Saigopalakrishna S. Yerneni, Phil Campbell, Boyle Cheng, and et al. 2021. "Development and Characterization of Novel Conductive Sensing Fibers for In Vivo Nerve Stimulation" Sensors 21, no. 22: 7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21227581

APA StyleRichter, B., Mace, Z., Hays, M. E., Adhikari, S., Pham, H. Q., Sclabassi, R. J., Kolber, B., Yerneni, S. S., Campbell, P., Cheng, B., Tomycz, N., Whiting, D. M., Le, T. Q., Nelson, T. L., & Averick, S. (2021). Development and Characterization of Novel Conductive Sensing Fibers for In Vivo Nerve Stimulation. Sensors, 21(22), 7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21227581