Robotic-Based Well-Being Monitoring and Coaching System for the Elderly in Their Daily Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

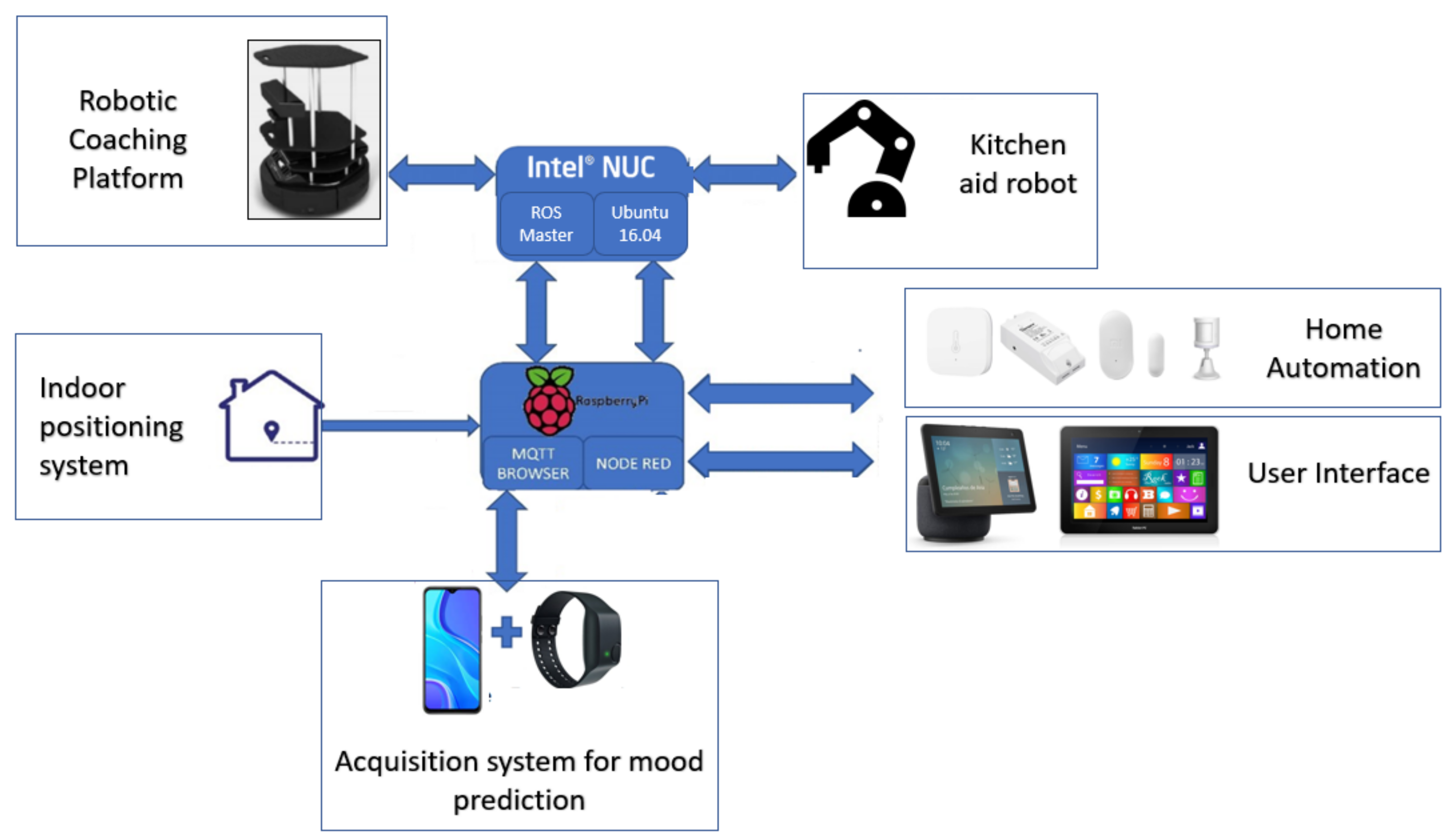

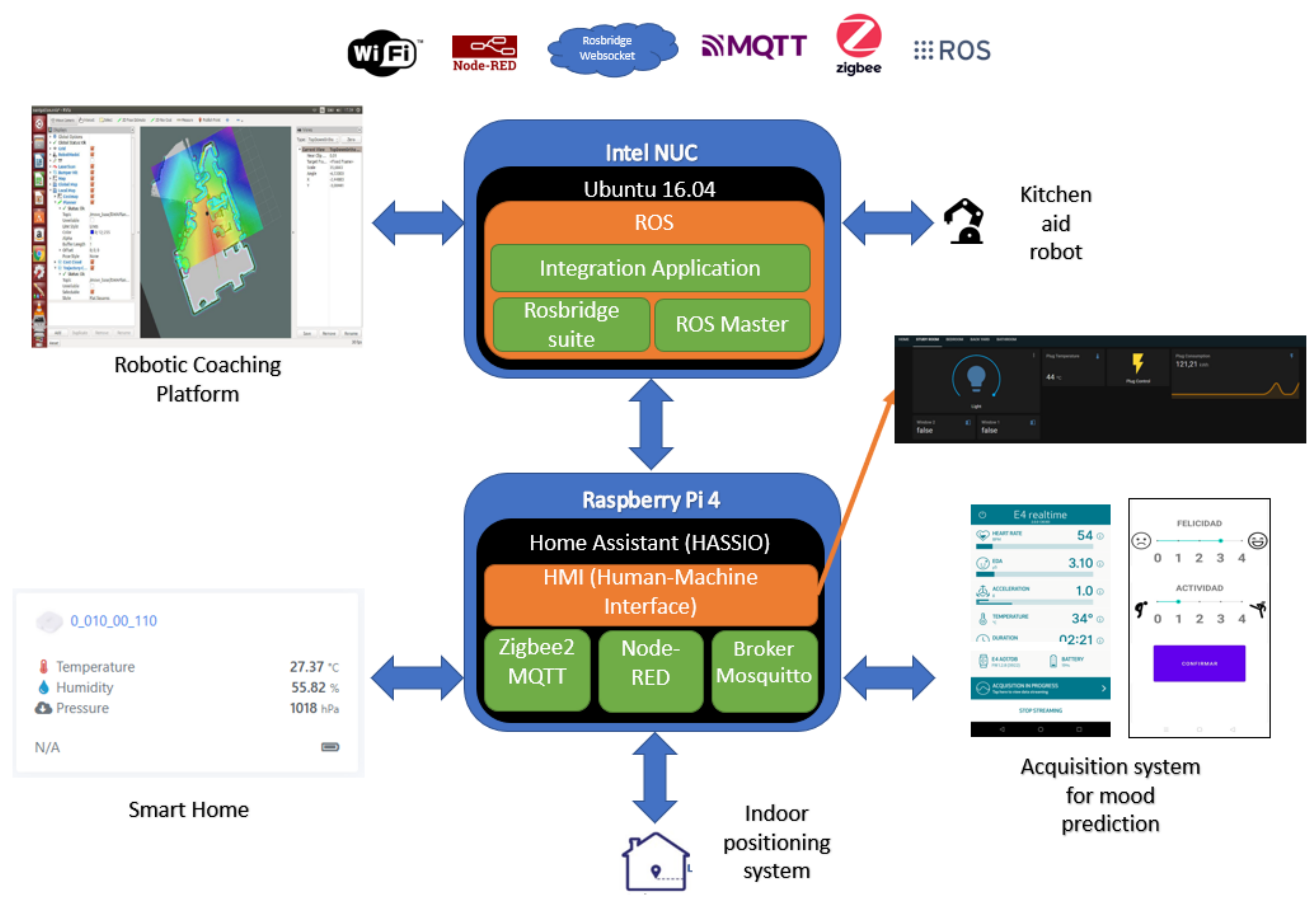

- General scheme, both software and hardware proposed. This section will present the general hardware/software composition including elements such as the robotic platform, the sensors for home automation and user monitoring, the actuators, the data acquisition system for mood estimation, the user interface and so forth.

- Integration of the proposed elements. The proposed test system and the integration achieved in the field of mobile robotic platform and home automation will be discussed.

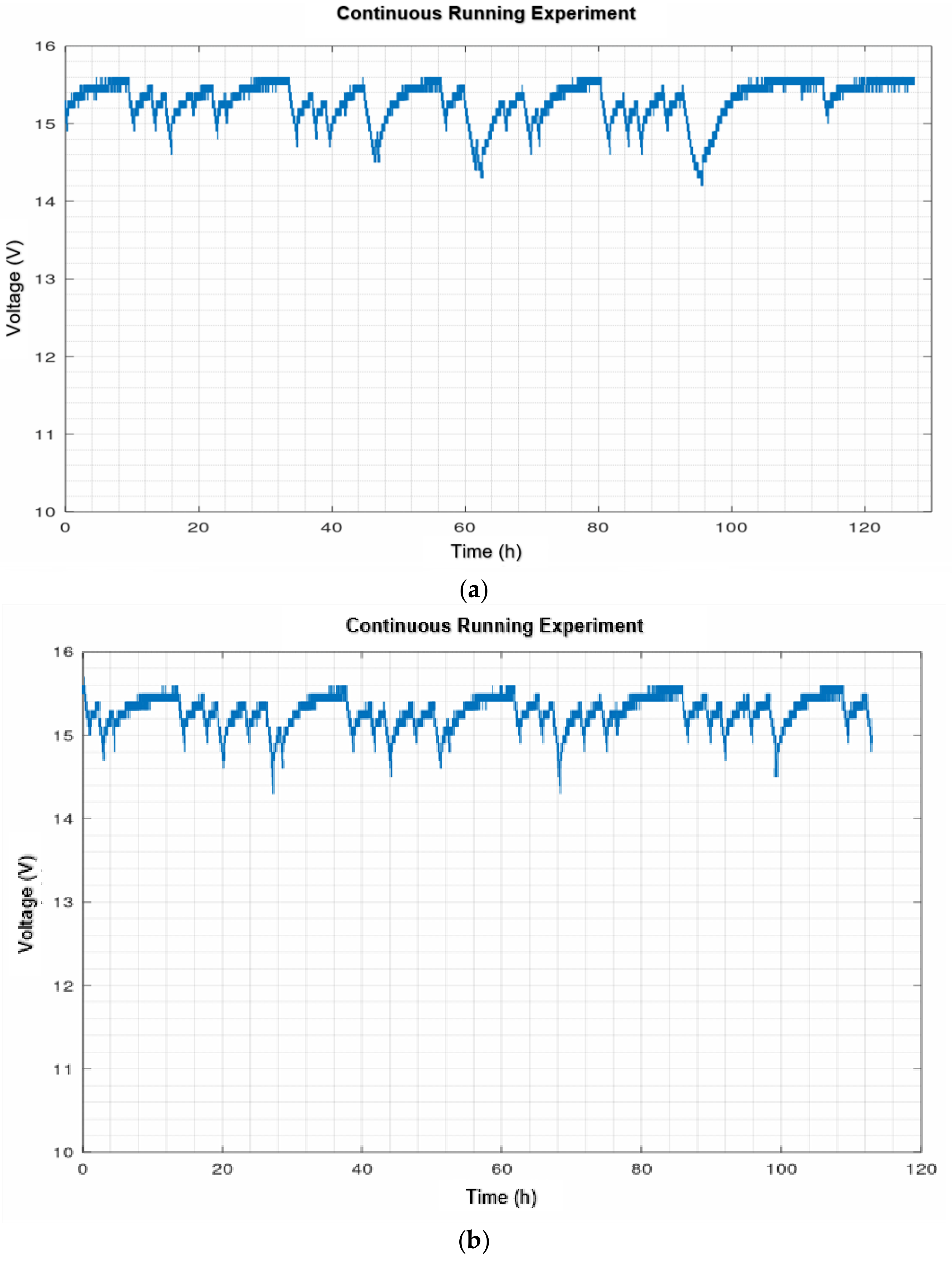

- Robustness of the navigation of the robotic platform. The navigation system implemented on the robotic platform will be discussed together with the continuous operation tests. In this way it will be possible to discuss whether autonomous navigation needs more sophisticated navigation strategies. The autodocking algorithm offered for the Kobuki robotic base will also be tested for robustness in continuous operation. With the continuous running test, the autonomy of the robotic system will be observed.

- Mood prediction. The data acquisition system designed for conducting the experiment in an everyday environment is discussed. On the other hand, the machine learning strategy to be used for mood prediction is also discussed. In addition, the psychological tools to be used (questionnaires and EMAs) are presented.

2. Related Works

2.1. Assistive Robotics

2.2. Smart Home

2.3. Wearables in Affective Computing

2.3.1. Wearables and Emotional Biomarkers

- Heart Rate. Heart rate is controlled by the autonomic nervous system, which comprises both sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) branches, whose action is normally balanced. When exposed to a stressor, this balance is lost, increasing the activity of the sympathetic branch, which leads to higher heart rates. In order to have a continuous indicator of this regulation, heart rate variability analysis is performed by studying the frequency contents of the spectral representation of the Inter-Beat-Interval time series (IBI) [85]. Mean and median frequency values of the power spectral density (PSD) of the IBI spectrum have been proposed as indicators [36]. Special care should be taken when performing the spectral transformation since this series is not evenly sampled by nature. Time-domain parameters such as RMSSD, NN50 and pNN50 are also considered [42,77,78,86,87].

- Brain activity. Through there are some works related to emotion detention in-the-wild based on electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis, there are some serious concerns limiting the practical application of these methods. Most of them are related to the reduced signal-to-noise-ratio achieved in real life conditions due to the small amplitude of the recorded signals and their susceptibility to artifacts (i.e., eyeblinks, heartbeats, jaw and forehead muscle tension) and electromagnetic perturbations [79].

- Other. With the advent of smartphone integrated sensors, some studies have taken advantage of them to build huge lifelogging datasets including signals from the built-in inertial sensors (accelerometer, gyroscope ad magnetometers), compass sensors, environmental parameters sensors such as sound and light levels and air pressure, humidity, and temperature as well as other as location and phone state [81,82,83].

2.3.2. Recommended Devices

2.4. Contributions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Proposed System Design

3.1.1. Hardware Architecture

3.1.2. Software Design

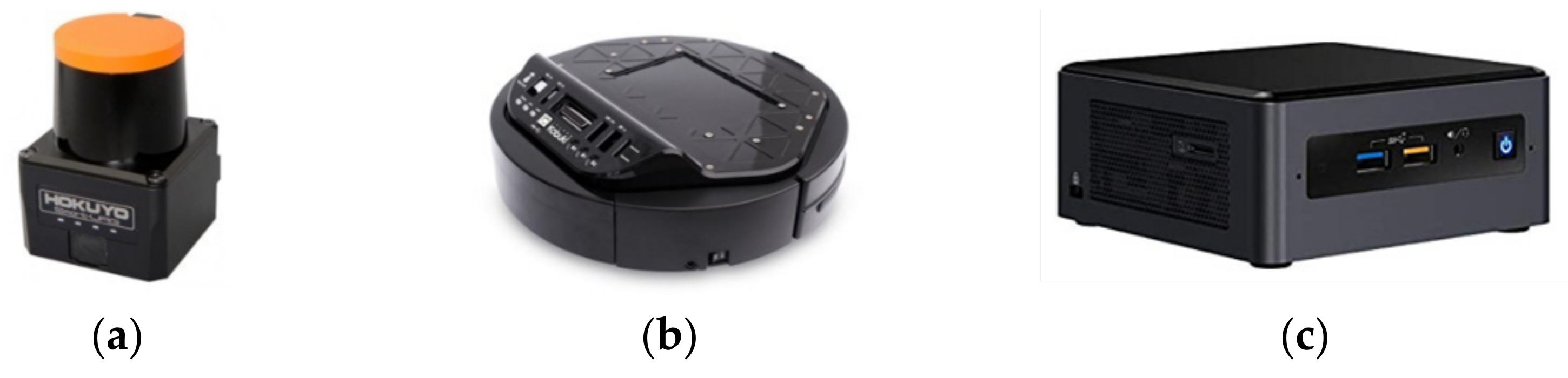

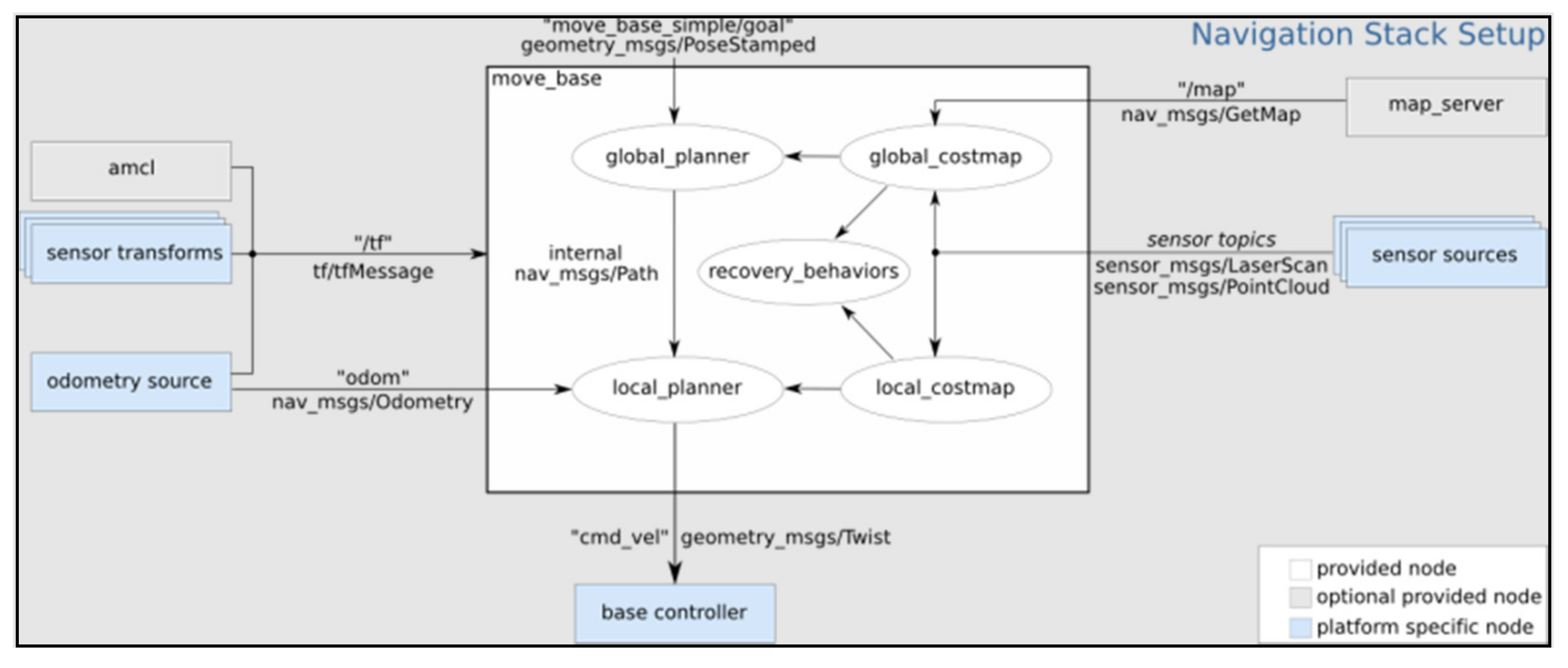

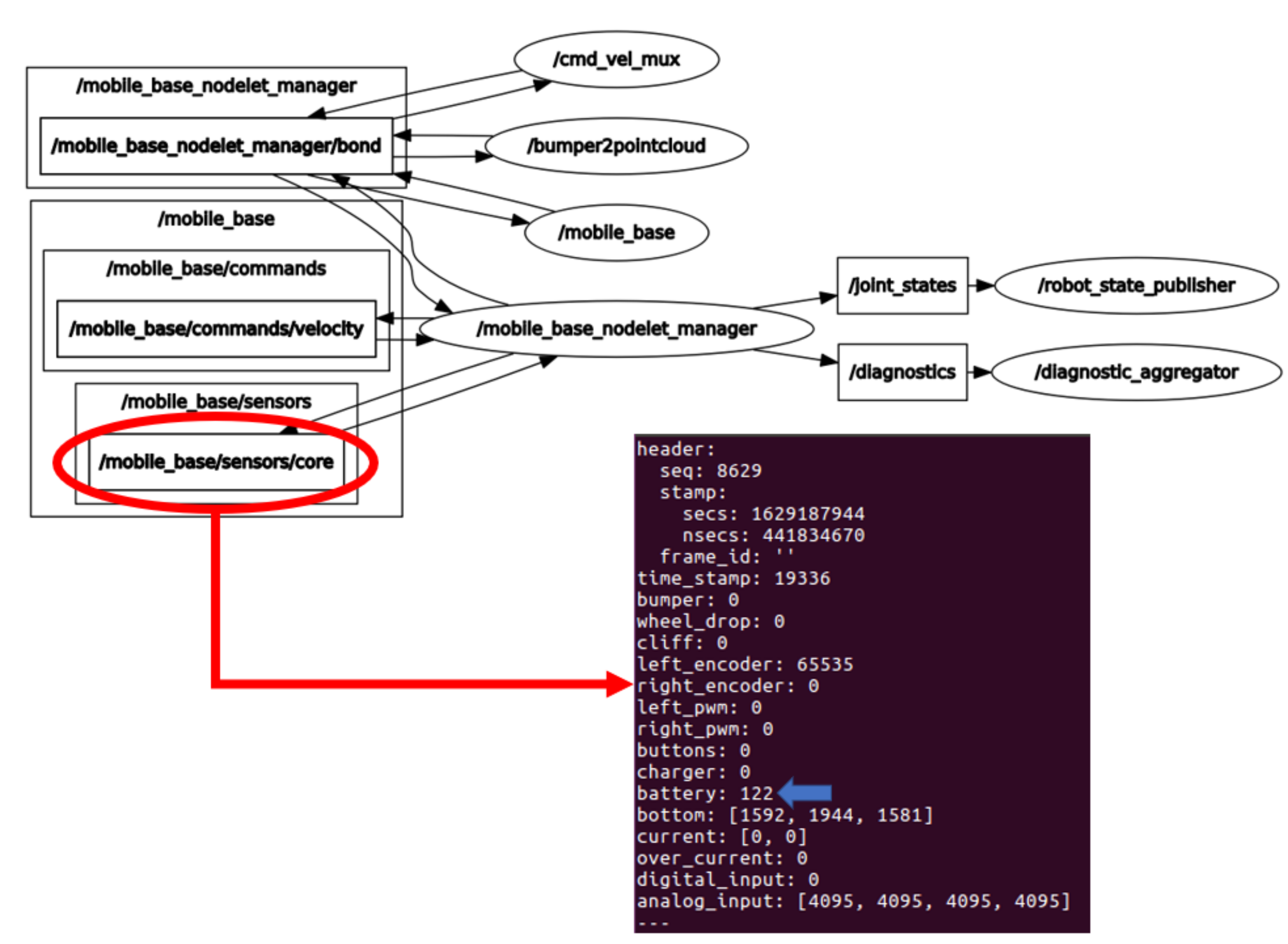

- Robotics platforms. Of the robotic platforms in Figure 1, only the emotional coaching platform will be explained because the other platform is being developed by the in the HIMTAE Project in the Carlos III University of Madrid. The teleoperated mapping, autonomous navigation, autodocking and power management software to determine its performance in continuous operation has already been implemented and tested. Further features and enhancements are under development.

- Smart home. The software that will run all the home automation logic is the Home Assistant operating system [93], selected because of its integration tools and the associated community for troubleshooting. It will run a Node-RED server and a Mosquitto MQTT broker. In addition, it also allows the use of the CC2531 USB dongle.

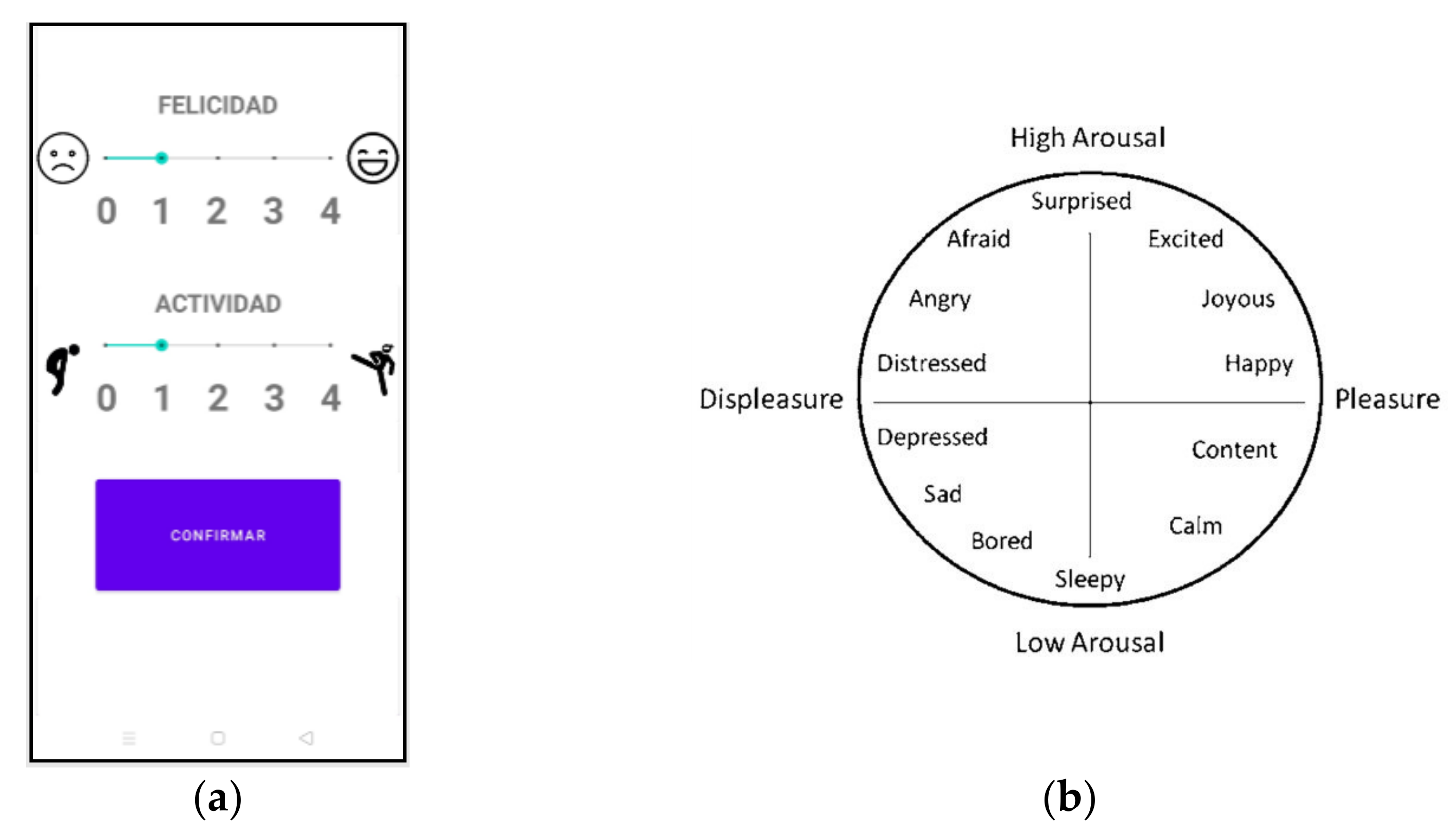

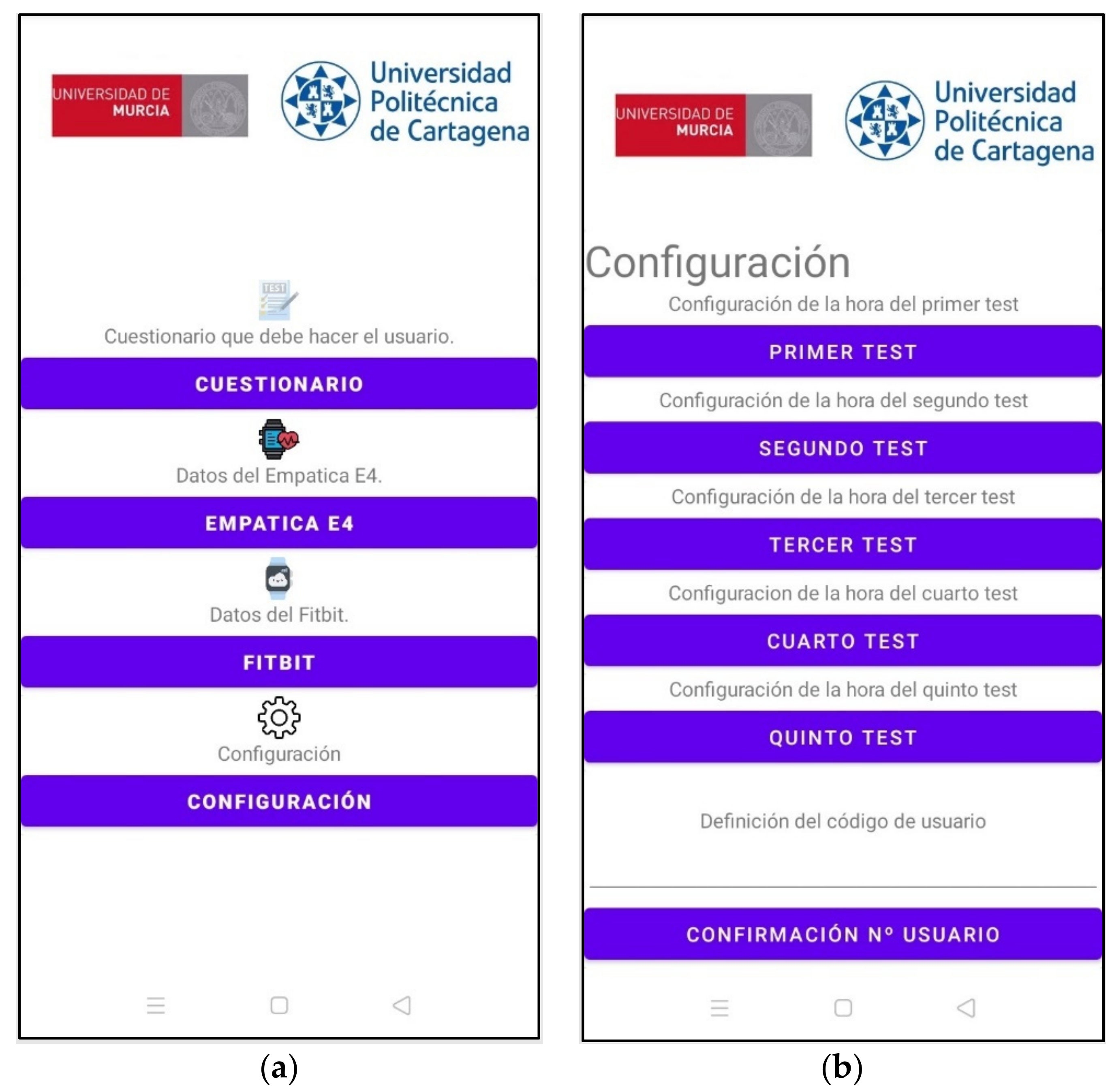

- Acquisition system for affective state prediction. As can be seen in Figure 1, at the hardware level, this system consists of an Empatica E4 medical device and a smartphone. Two Android applications are used for the extraction of the data used in mood prediction. The first one, E4 RealTime, is the official application offered by Empatica for the extraction of physiological data. There is also a self-developed application for conducting tests and questionnaires to relate physiological data to mood states. The final idea is that this whole process will take place in a single application.

- General integration system. This is the system in charge of carrying out the integration between the elements. There will only be differentiation at the level of sensors and actuators, regardless of the brand or manufacturer. This whole system will be developed on Ubuntu 16.04 and ROS. The use of ROS to carry out this task is justified by the fact that the integration, in some cases, is direct. Furthermore, being structured in nodes, the topics and following the publisher/subscriber policy makes development more accessible. The development of this application is not yet complete. For the time being, the integration paths have been basically developed and tested in a lightweight way. For example, the integration between Node-RED and ROS has been tested, as has the integration between elements with ROS, the integration between Zigbee and Node-RED elements with MQTT and between Android and Node-RED using MQTT. The integration application is currently in the conceptual development phase.

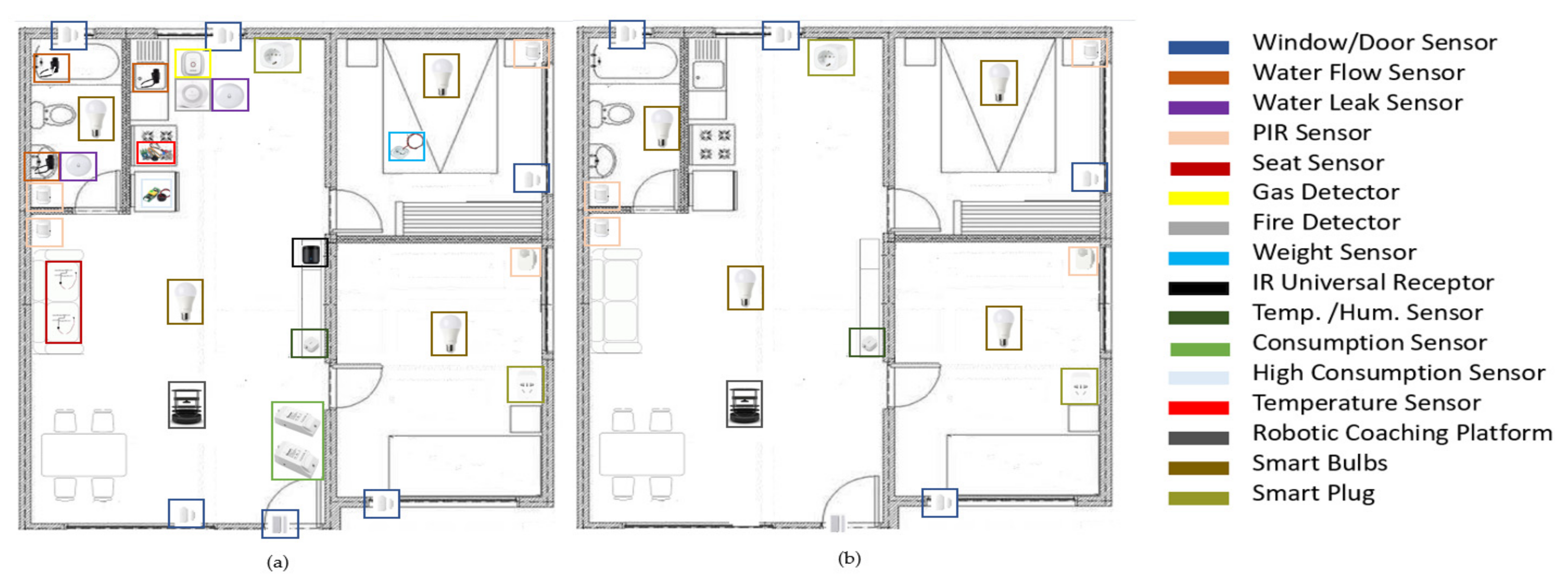

3.2. Home Automation

3.2.1. Sensor Environment

3.2.2. Computer Platform for Home Automation

3.3. Robotic Platform

3.4. Mood Estimation

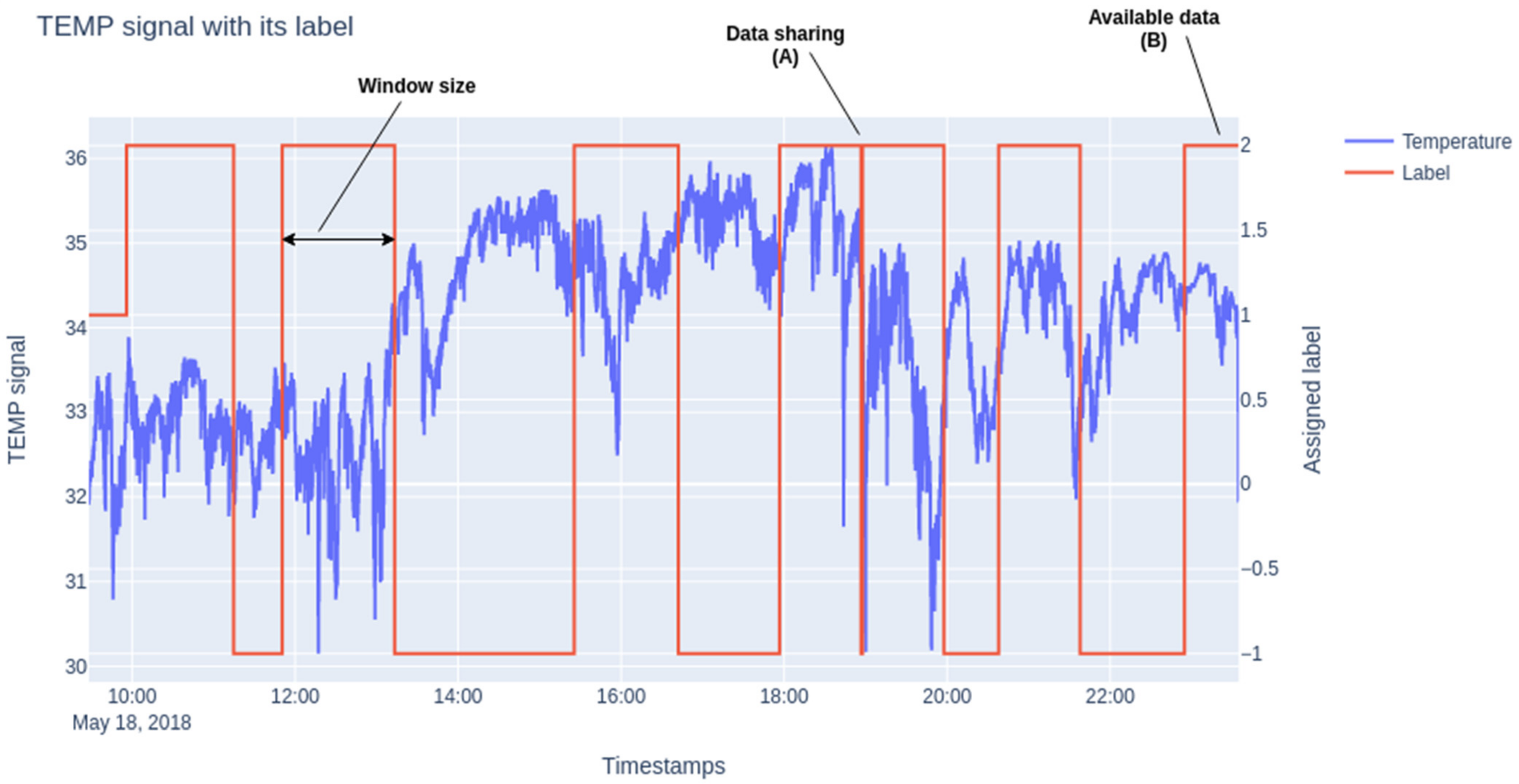

3.4.1. Acquisition and Processing of Physiological Signals

- (a)

- Physiological Signal Processing and Feature Extraction

- (b)

- 3-axis Accelerometer (72 features)

- (c)

- Peripheral Skin Temperature (13 features)

- (d)

- Heart rate variability (27 features)

- (e)

- Electrodermal Activity (82 features)

3.4.2. Mobile App for Ground Truth

3.4.3. Signal Classification

3.5. Psychological Instruments

- A sociodemographic survey that provided information on age, gender, marital status and knowledge of digital devices (mobile, computer, etc.).

- A short Inventory of Emotional Intelligence for the Elderly (EQ-I-M20) by Pérez-Fuentes, Gázquez, Mercader and Molero [106]. This is an adaptation and validation into Spanish of the Bar-On and Parker [107] instrument for the elderly consisting of 20 items on Likert scale. It is made up of the following factors: (a) Intrapersonal; (b) Interpersonal; (c) Stress management; (d) Adaptability; and (e) General mood. It has a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.89 for reliability on the general scale.

- CECAVIR (Quality of Life Assessment Questionnaire) prepared by Molero, Pérez-Fuentes, Gázquez and Mercader [108] consisting of 56 items ranging from 1 to 5 composed of six quality of life dimensions: Health, Social and family relationships, Activity and leisure, Environmental quality, Functional capacity and Satisfaction with life. It has a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.865 on the global scale.

- STAI, State Trait Anxiety Questionnaire [109]. It is a questionnaire made up of 40 items with two scales. It can evaluate anxiety as a transitory state (Anxiety/state) and as a latent trait (Anxiety/trait). The alpha coefficient for State Anxiety ranges between 0.90 and 0.93 and for Trait Anxiety between 0.84 and 0.87 [109].

- Hamilton scale on depressive/anxiety symptoms (1960) [110] made up of 14 items on a Likert scale that ranges from 0 to 4 to evaluate somatic and respiratory symptoms, depression, and so forth. A higher score indicatives anxiety/depressive symptoms and provides information on psychic and somatic anxiety.

- Abbreviated Yesavage questionnaire (GDS) on depression in its Spanish version for the elderly [111], a questionnaire that evaluates depression in people over 65 years of age, made up of 15 items that score dichotomously (0–1). A total score over 5 indicates depression. It has an internal consistency of 0.994.

- Mini-cognitive exam -MEC35- [112], the Spanish adaptation of the Mini-Mental State Examination. It is an instrument that detects cognitive deterioration and examines different cognitive functions: orientation, memory, attention, calculation, language and construction, praxis and reasoning. The maximum score is 35 points, the optical cut-off points for cognitive impairment being in a population over 65 years of age and with a low educational level of 24 points.

- The Global Impairment Scale (GDS) by Reisberg, Ferris, de León and Crook (1982) [113], assesses the seven different phases of Alzheimer’s disease: stage 1 (normal), stage 2 (subjective memory complaint), stage 3 (mild cognitive impairment), stage 4 (mild dementia), stage 5 (moderate dementia), stage 6 (moderately severe dementia) and stage 7 (severe dementia). The internal consistency is very good, presenting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 [113].

- The Katz index [114], which assesses the level of dependence/independence of daily activities. It has eight possible levels: (A) Independent in all its functions; (B) Independent in all functions except one; (C) Independent in all functions except in the bathroom or other; (D) Independent in all functions except in the bathroom, dress and any other; (E) Independent in all functions except in the bathroom, dress, use of the toilet and any other; (F) Independence in all functions except in the bathroom, dress, use of the toilet, mobility and any other of the remaining two; (G) Dependent in all functions; (H) Dependent in at least two functions, but not classifiable as C, D, E or F. Levels A–B (0–1 points) indicate absence of disability or mild disability, levels C–D (2–3 points) indicate moderate disability and E–G levels (4–6 points) indicate severe disability.

- Psychological well-being Scale (Díaz, Rodríguez-Carvajal, Blanco, Moreno-Jiménez, Gallardo and Valle, 2006) [115], an instrument that consists of 29 items that ranges from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). It has six subscales that evaluates self-acceptance, personal growth, purpose in life, positive relationships with others, environmental mastery and autonomy. It is Cronbach’s alpha ranges between 0.70 and 0.83 in all dimensions (Díaz et al., 2006) [115].

- Scales on positive and negative affect (PANAS), translated into Spanish by Robles and Páez [116] (2003), a scale composed of two factors of 10 items (ranging from 1 not at all or slightly to 5 a lot) that measures positive and negative affect and presents a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 for positive and 0.88 for negative affect (Robles and Páez, 2003) [116].

- NeO-FFI Questionnaire (Costa and McCrae, 1999) [117], a reduced version of the well-known NEO-PI-R. The questionnaire consists of 60 items to assess personality according to the “big five” model (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Friendliness and Responsibility).

3.6. Experimental Design for Mood Prediction

4. Results

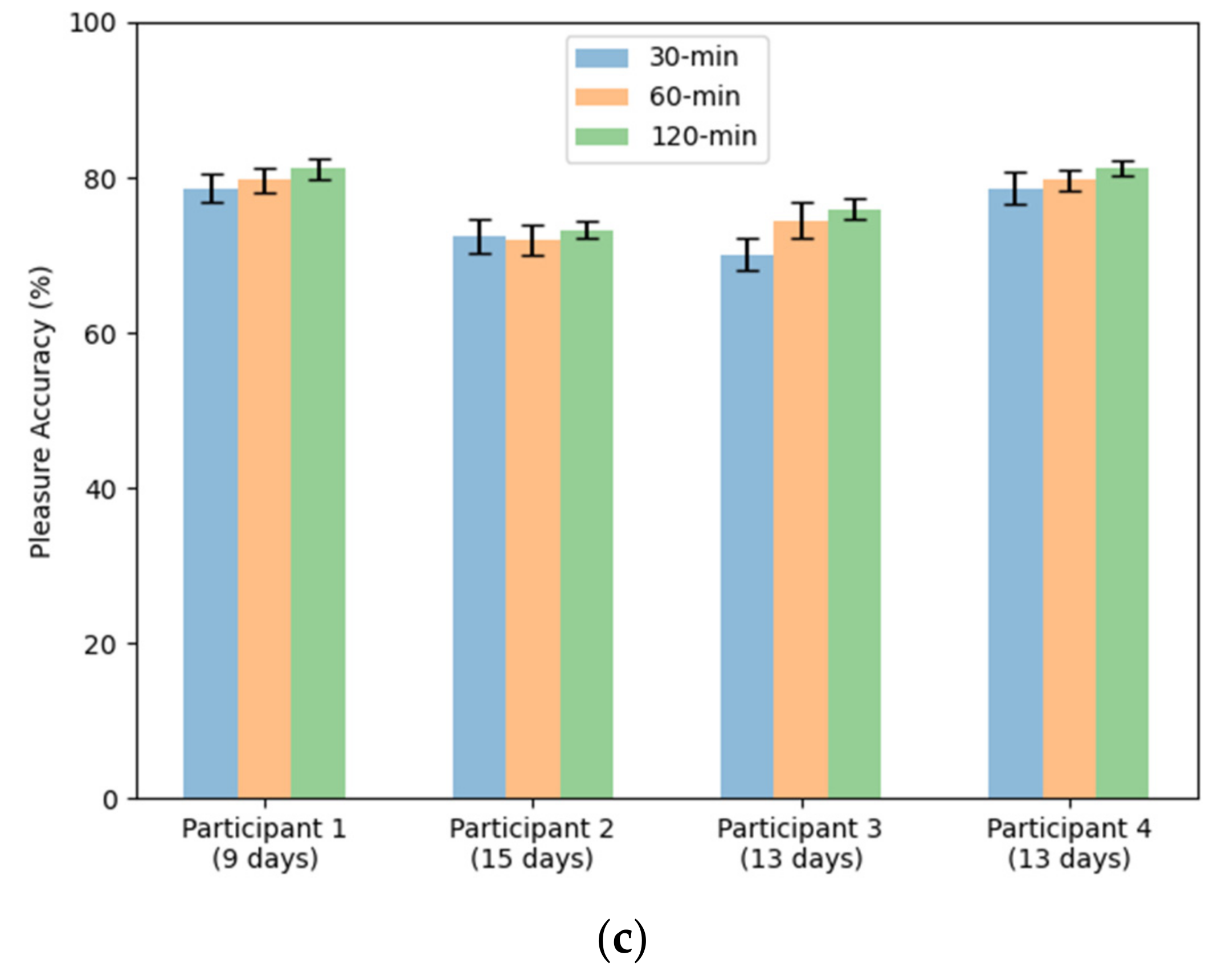

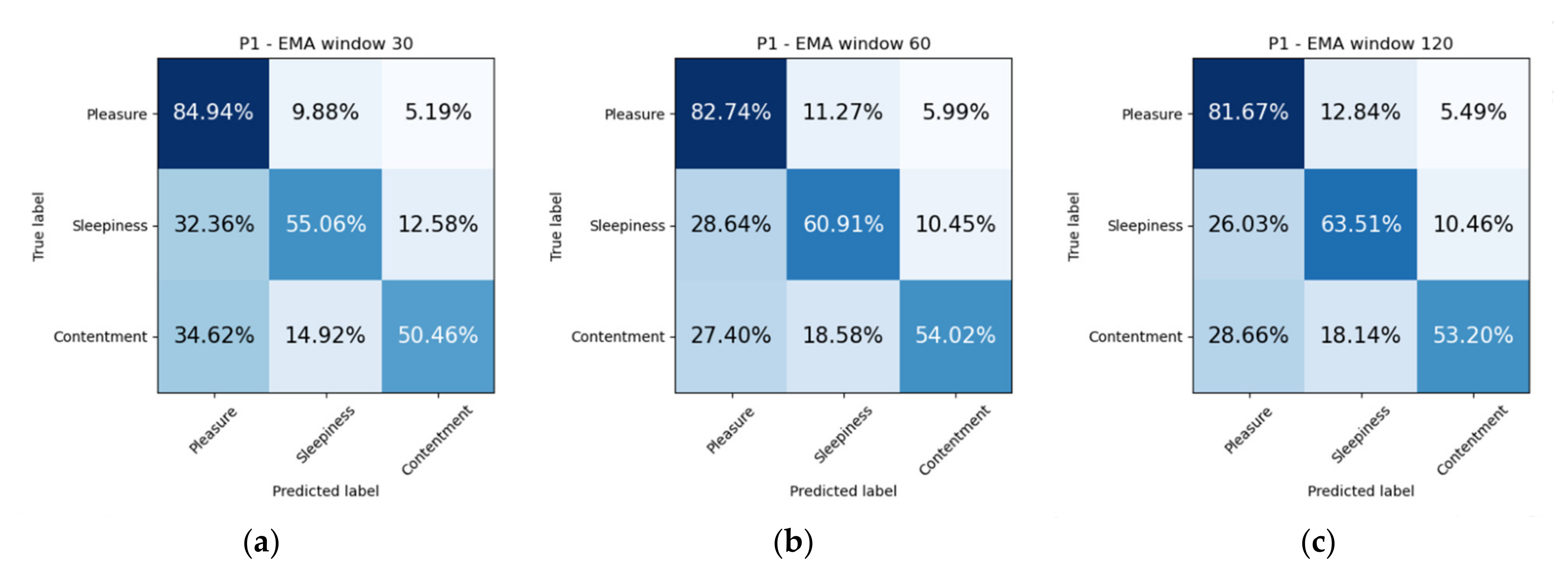

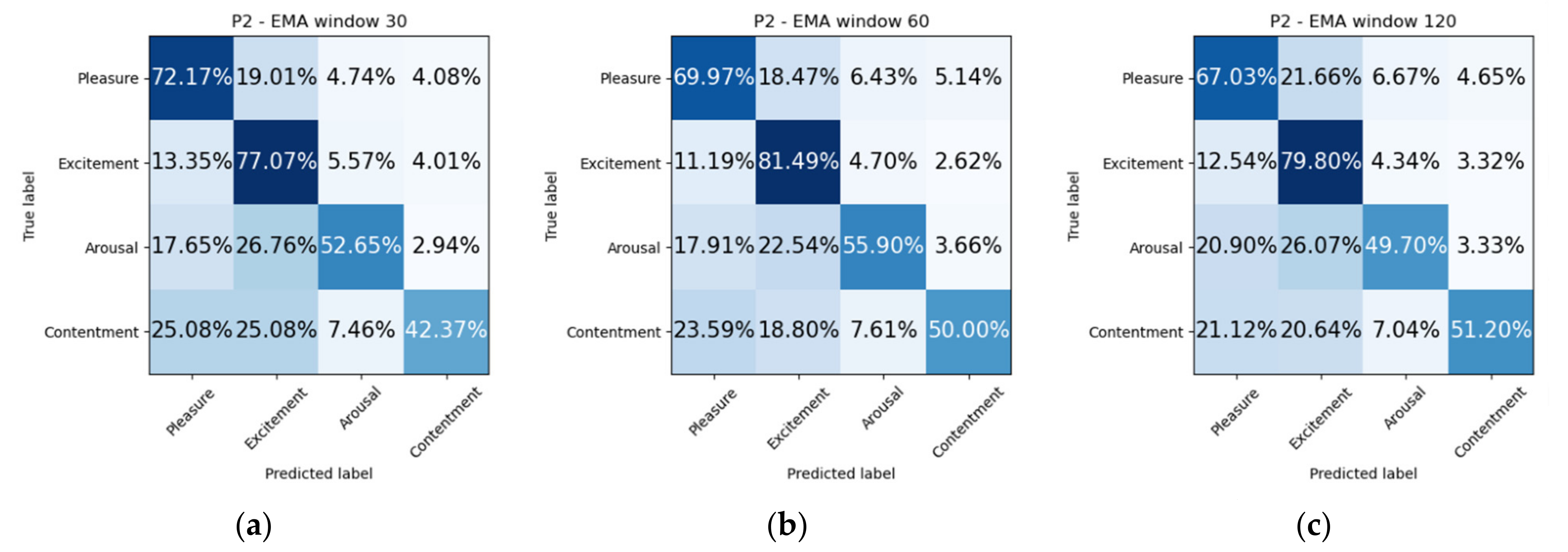

4.1. Mood Prediction Resutls

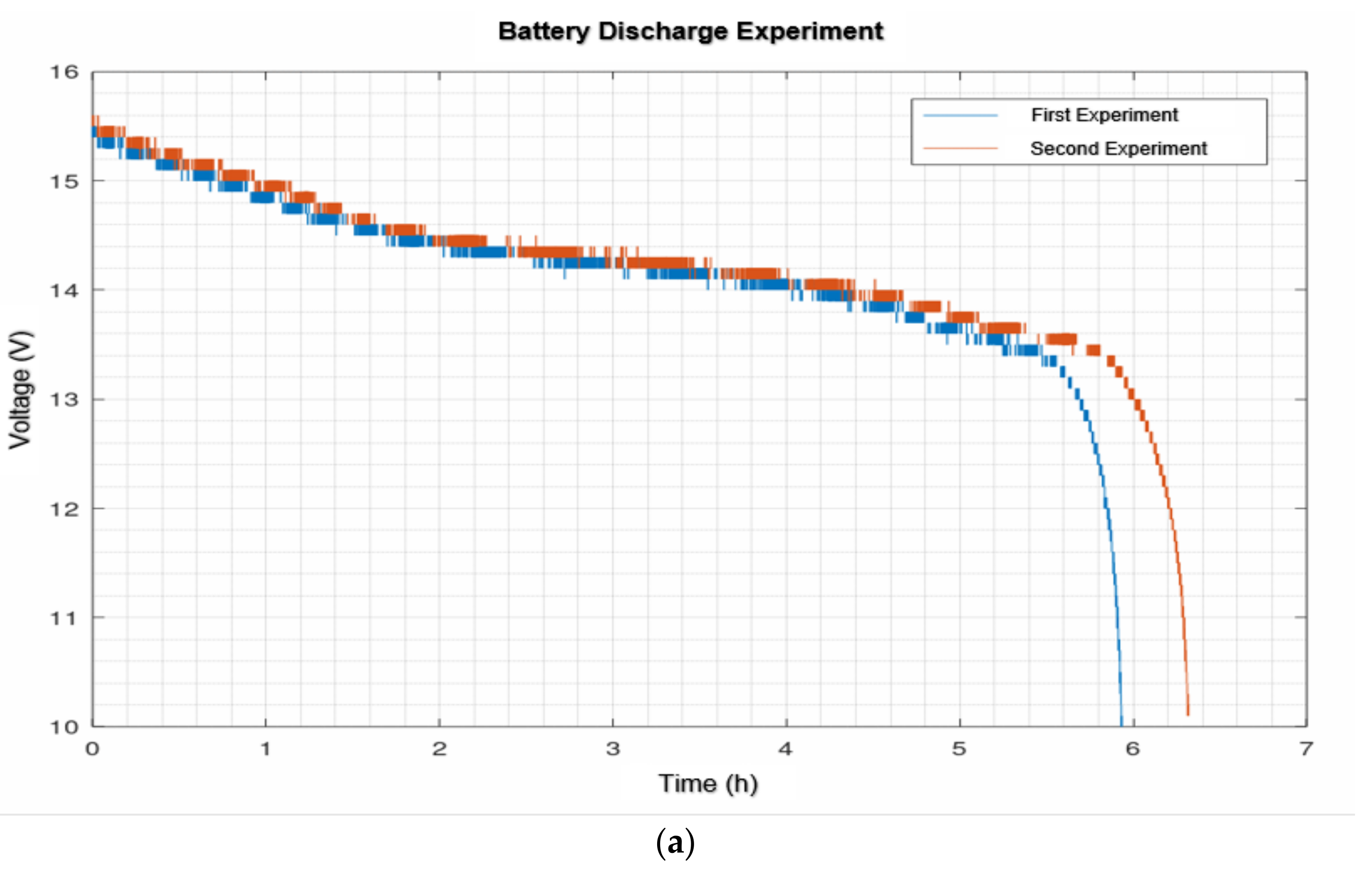

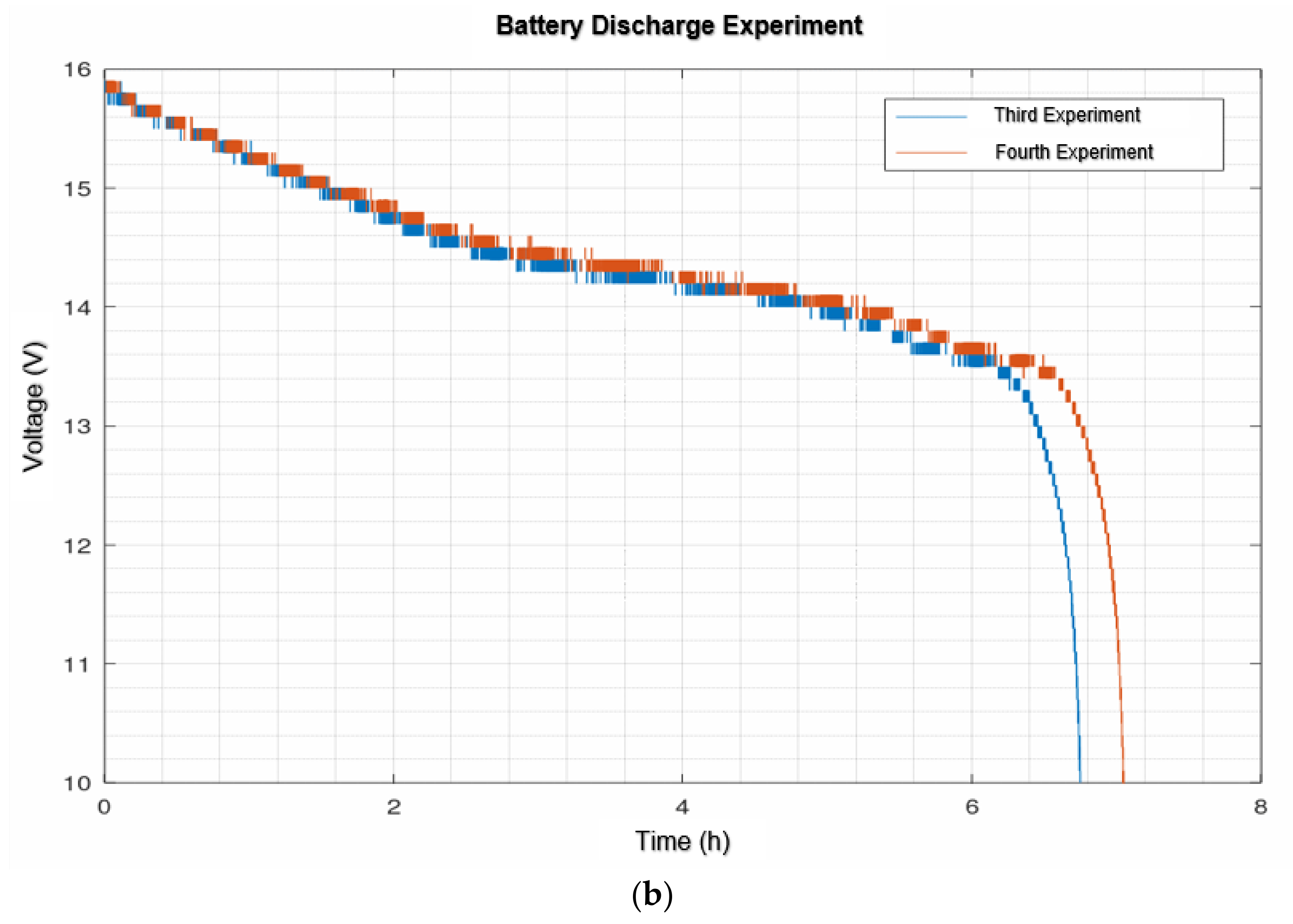

4.2. Robotic Platform Continuous Operation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Mood Prediction

5.2. Robotic Platform

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EUROSTAT. Mortality and Life Expectancy Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Mortality_and_life_expectancy_statistics (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Freire Rodríguez, C.; Ferradás Canedo, M.d.M. Calidad de Vida y Bienestar en la Vejez; Ediciones Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH) 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/ech_2018.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Unsar, S.; Dindar, I.; Kurt, S. Activities of daily living, quality of life, social support and depression levels of elderly individuals in Turkish society. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2015, 65, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. The Potential Public Health Relevance of Social Isolation and Loneliness: Prevalence, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2017, 27, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE. Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH) 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/ech_2020.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Pinazo-Hernandis, S. Impacto psicosocial de la COVID-19 en las personas mayores: Problemas y retos. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2020, 55, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtlebot. TurtleBot2. Available online: https://www.turtlebot.com/turtlebot2/ (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Bautista-Salinas, D.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Mendez, I.; Mozos, O.M. Monitoring and Prediction of Mood in Elderly People during Daily Life Activities. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.T.; Kuo, C.; Cheng, H.T.; Buthpitiya, S.; Collins, P.; Griss, M. Activity-aware mental stress detection using physiological sensors. In Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 76. [Google Scholar]

- Mozos, O.M.; Sandulescu, V.; Andrews, S.; Ellis, D.; Bellotto, N.; Dobrescu, R.; Ferrandez, J.M. Stress detection using wearable physiological and sociometric sensors. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2017, 27, 1650041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovsepian, K.; Al’absi, M.; Ertin, E.; Kamarck, T.; Nakajima, M.; Kumar, S. CStress: Towards a gold standard for continuous stress assessment in the mobile environment. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Osaka, Japan, 7–11 September 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.A.; Picard, R.W. Detecting stress during real-world driving tasks using physiological sensors. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2005, 6, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazine, D. El Robot Panasonic Hospi Rimo Ayuda en el Transporte de Fármacos a los Pacientes Hospitalizados. Available online: https://www.digitalavmagazine.com/2013/10/29/el-robot-panasonic-hospi-rimo-ayuda-en-el-transporte-de-farmacos-a-los-pacientes-hospitalizados/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Grupo ADD. Robot Moxi. Available online: https://grupoadd.es/el-robot-moxi (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Bhattacharjee, T.; Lee, G.; Song, H.; Srinivasa, S.S. Towards Robotic Feeding: Role of Haptics in Fork-Based Food Manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werle, J.; Hauer, K. Design of a bath robot system—User definition and user requirements based on International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). In Proceedings of the 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, New York, NY, USA, 26–31 August 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.H.; Chen, T.L.; Jain, A.; Kemp, C.C. Towards an assistive robot that autonomously performs bed baths for patient hygiene. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ 2010 International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsung. Samsung Bots, los Compañeros del Futuro. 2019. Available online: https://news.samsung.com/co/samsung-bot-los-mejores-companeros-roboticos-en-camino-a-enriquecer-la-calidad-de-vida-de-las-personas (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- García, E. Rassel, el Robot que Ayuda a las Personas Mayores. 2018. Available online: https://cadenaser.com/emisora/2018/12/07/radio_valencia/1544174190_652009.html (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Pages, J.; Marchionni, L.; Ferro, F. TIAGo: The Modular Robot That Adapts to Different Research Needs. In Proceedings of the IROS Workshop on Robot Modularity; 2016; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://clawar.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/P2.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Kamel, E.; Memari, A.M. State-of-the-Art Review of Energy Smart Homes. J. Archit. Eng. 2019, 25, 03118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonnote, N.; Høyland, K. Smart home technologies that support independent living: Challenges and opportunities for the building industry–a systematic mapping study. Intell. Build. Int. 2017, 9, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiyama, T. In-home health monitoring system for solitary elderly. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 63, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigini, L.; Bovi, G.; Panzarino, C.; Gower, V.; Ferratini, M.; Andreoni, G.; Sassi, R.; Rivolta, M.W.; Ferrarin, M. Pilot Test of a New Personal Health System Integrating Environmental and Wearable Sensors for Telemonitoring and Care of Elderly People at Home (SMARTA Project). Gerontology 2017, 63, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, R.; De La Pinta, J.R.; Alvarez, A.; Maestre, J.M. Integration of service robots in the smart home by means of UPnP: A surveillance robot case study. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienke, J.; Wrede, S. A middleware for collaborative research in experimental robotics. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Kyoto, Japan, 20–22 December 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrede, S.; Leichsenring, C.; Holthaus, P.; Hermann, T.; Wachsmuth, S. The Cognitive Service Robotics Apartment: A Versatile Environment for Human–Machine Interaction Research. KI Kunstl. Intell. 2017, 31, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellocchio, E.; Costante, G.; Cascianelli, S.; Valigi, P.; Ciarfuglia, T.A. SmartSEAL: A ros based home automation framework for heterogeneous devices interconnection in smart buildings. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2nd International Smart Cities Conference: Improving the Citizens Quality of Life, Trento, Italy, 12–15 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchechukwu, D.; Siddique, A.; Maksatbek, A.; Afanasyev, I. ROS-based Integration of Smart Space and a Mobile Robot as the Internet of Robotic Things. In Proceedings of the Conference of Open Innovation Association, FRUCT, Helsinki, Finland, 5–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. Internet of Robotic Things: Concept, Technologies, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 9489–9500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, T.; Srivastava, S.; Pinto, A.; Kambhampati, S. An ROS-based shared communication middleware for plug and play modular intelligent design of smart systems. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.01133. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R.W.; Healey, J. Affective wearables. Pers. Technol. 1997, 1, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentland, A. Social Physics: How Social Networks Can Make Us Smarter. 2014. Available online: https://www.amazon.es/Social-Physics-Networks-Make-Smarter-ebook/dp/B00DMCUYRM (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Sarkar, N. Psychophysiological control architecture for human-robot coordination-concepts and initial experiments. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.02CH37292), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; Volume 4, pp. 3719–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.; Sarkar, N.; Smith, C.A.; Kirby, L.D. Anxiety detecting robotic system—Towards implicit human-robot collaboration. Robotica 2004, 22, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethel, C.L.; Salomon, K.; Murphy, R.R.; Burke, J.L. Survey of Psychophysiology Measurements Applied to Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the RO-MAN 2007—The 16th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Jeju Island, Korea, 26–29 August 2007; pp. 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, M. Emerging patient-driven health care models: An examination of health social networks, consumer personalized medicine and quantified self-tracking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 492–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarts, E.; Harwig, R.; Schuurmans, M. Ambient intelligence. In The Invisible Future: The Seamless Integration of Technology into Everyday Life; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberger, T.; Becker, M.; Ras, E.; Holzinger, A.; Müller, P. Ambient Intelligence in Assisted Living: Enable Elderly People to Handle Future Interfaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzo, A.; Montalban, I.; León, E.; Schlatter, S. Sentient: An Approach to Ambient Assisted Emotional Regulation. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ainara-Garzo/publication/259459808_Sentient_An_approach_to_Ambient_Assisted_Emotional_Regulation/links/0a85e533d3bffc5e98000000/Sentient-An-approach-to-Ambient-Assisted-Emotional-Regulation.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Karahanoğlu, A.; Erbuğ, Ç. Perceived Qualities of Smart Wearables: Determinants of User Acceptance; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawassizadeh, R.; Price, B.A.; Petre, M. Wearables: Has the age of smartwatches finally arrived? Commun. ACM 2014, 58, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oung, Q.W.; Hariharan, M.; Lee, H.L.; Basah, S.N.; Sarillee, M.; Lee, C.H. Wearable multimodal sensors for evaluation of patients with Parkinson disease. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), Penang, Malaysia, 27–29 November 2015; pp. 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B.; Baca, A. Wearables and Apps—Modern Diagnostic Frameworks for Health Promotion through Sport. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 2016, 2016, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometov, A.; Shubina, V.; Klus, L.; Skibińska, J.; Saafi, S.; Pascacio, P.; Flueratoru, L.; Gaibor, D.Q.; Chukhno, N.; Chukhno, O.; et al. A Survey on Wearable Technology: History, State-of-the-Art and Current Challenges. Comput. Netw. 2021, 193, 108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Dian, F.; Vahidnia, R.; Rahmati, A. Wearables and the Internet of Things (IoT), Applications, Opportunities, and Challenges: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 69200–69211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkilä, J. Designing for Smart Clothes and Wearables—User Experience Design Perspective. In Smart Textiles: Fundamentals, Design, and Interaction; Schneegass, S., Amft, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, S.; Steed, J.; Coulter, J. Spheres of Practice for the Co-design of Wearables. J. Text. Des. Res. Pract. 2016, 4, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Gouge, C.; Crilley, M. Design principles for health wearables. Commun. Des. Q. 2017, 5, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebbe, R.; Steinert, A.; Müller-Werdan, U. Wearables for Older Adults: Requirements, Design, and User Experience. In Perspectives on Wearable Enhanced Learning (WELL): Current Trends, Research, and Practice; Buchem, I., Klamma, R., Wild, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, V.G.; Caine, K. Users’ Privacy Concerns About Wearables; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwek, L.; Ellis, D.A.; Andrews, S.; Joinson, A. The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yetisen, A.K.; Martinez-Hurtado, J.L.; Ünal, B.; Khademhosseini, A.; Butt, H. Wearables in Medicine. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiauzzi, E.; Rodarte, C.; DasMahapatra, P. Patient-centered activity monitoring in the self-management of chronic health conditions. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espay, A.J.; Bonato, P.; Nahab, F.B.; Maetzler, W.; Dean, J.M.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M.; Merola, A.; Horak, F.; Lang, A.E.; et al. Technology in Parkinson’s disease: Challenges and opportunities. Mov. Disord. 2016, 31, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.L.; Dinesh, K.; Xiong, M.; Tarolli, C.G.; Sharma, S.; Sheth, N.; Aranyosi, A.J.; Zhu, W.; Goldenthal, S.; Biglan, K.M.; et al. Multiple Wearable Sensors in Parkinson and Huntington Disease Individuals: A Pilot Study in Clinic and at Home. Digit. Biomark. 2017, 1, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Din, S.; Elshehabi, M.; Galna, B.; Hobert, M.A.; Warmerdam, E.; Suenkel, U.; Brockmann, K.; Metzger, F.; Hansen, C.; Berg, D.; et al. Gait analysis with wearables predicts conversion to Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 86, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pau, M.; Caggiari, S.; Mura, A.; Corona, F.; Leban, B.; Coghe, G.; Lorefice, L.; Marrosu, M.G.; Cocco, E. Clinical assessment of gait in individuals with multiple sclerosis using wearable inertial sensors: Comparison with patient-based measure. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2016, 10, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Farrow, S.; Motl, R.W.; Chitnis, T. Wearable biosensors to monitor disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2017, 7, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Y.; McGinnis, R.S.; Seagers, K.; Motl, R.W.; Sheth, N.; Wright, J.A., Jr.; Ghaffari, R.; Sosnoff, J.J. Monitoring gait in multiple sclerosis with novel wearable motion sensors. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psarakis, M.; Greene, D.A.; Cole, M.H.; Lord, S.R.; Hoang, P.; Brodie, M. Wearable technology reveals gait compensations, unstable walking patterns and fatigue in people with multiple sclerosis. Physiol. Meas. 2018, 39, 075004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparaco, M.; Lavorgna, L.; Conforti, R.; Tedeschi, G.; Bonavita, S. The Role of Wearable Devices in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Int. 2018, 2018, e7627643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frechette, M.L.; Meyer, B.M.; Tulipani, L.J.; Gurchiek, R.D.; McGinnis, R.S.; Sosnoff, J.J. Next Steps in Wearable Technology and Community Ambulation in Multiple Sclerosis. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, L.; Hodgkinson, W.; Smith, C.; Dodd, J.M.; Sharrack, B.; Mazzà, C.; Paling, D. Wearable sensors can reliably quantify gait alterations associated with disability in people with progressive multiple sclerosis in a clinical setting. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Landero, F.; García-Magariño, I.; Lacuesta, R.; Lloret, J. Green Communication for Tracking Heart Rate with Smartbands. Sensors 2018, 18, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaim, W.B.; Ometov, A.; Molinaro, A.; Lener, I.; Campolo, C.; Lohan, E.S.; Nurmi, J. Towards Energy Efficiency in the Internet of Wearable Things: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 175412–175435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Vanijja, V.; Arpnikanondt, C.; Zhang, X.; Papasratorn, B. A Quantitative Approach for Evaluating the Quality of Experience of Smart-Wearables From the Quality of Data and Quality of Information: An End User Perspective. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 64266–64278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbunan-Fich, R. User Satisfaction with Wearables. AIS Trans. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kang, H. User engagement with smart wearables: Four defining factors and a process model. Mob. Media Commun. 2021, 9, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbunan-Fich, R. An affordance lens for wearable information systems. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, D.; McCaffrey, D. Inside Wearables: How the Science of Human Behavior Change Offers the Secret to Long-Term Engagement; Endeavour Partners LLC: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Canhoto, A.I.; Arp, S. Exploring the factors that support adoption and sustained use of health and fitness wearables. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smuck, M.; Odonkor, C.A.; Wilt, J.K.; Schmidt, N.; Swiernik, M.A. The emerging clinical role of wearables: Factors for successful implementation in healthcare. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepa, L.; Capecci, M.; Ceravolo, M.G. Smartwatch based emotion recognition in Parkinson’s disease. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Consumer Technologies (ISCT), Ancona, Italy, 19–21 June 2019; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Guimbretière, F.; Jung, M.F.; Choudhury, T. BoostMeUp: Improving Cognitive Performance in the Moment by Unobtrusively Regulating Emotions with a Smartwatch. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2019, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, Z.; Zhou, P.; Li, M. Memento: An Emotion-driven Lifelogging System with Wearables. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2019, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahian, M.J.; Ghosh, T.; Uddin, M.N.; Islam, M.M.; Mahmud, M.; Kaiser, M.S. Towards Artificial Intelligence Driven Emotion Aware Fall Monitoring Framework Suitable for Elderly People with Neurological Disorder; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaizman, Y.; Ellis, K.; Lanckriet, G. Recognizing Detailed Human Context In-the-Wild from Smartphones and Smartwatches. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1609.06354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaizman, Y.; Ellis, K.; Lanckriet, G.; Weibel, N. ExtraSensory App: Data Collection In-the-Wild with Rich User Interface to Self-Report Behavior. In Proceedings of the CHI ’18: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.; Al-Jefri, M.; Lee, J. Using Machine Learning and Smartphone and Smartwatch Data to Detect Emotional States and Transitions: Exploratory Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saganowski, S.; Dutkowiak, A.; Dziadek, A.; Dzieżyc, M.; Komoszyńska, J.; Michalska, W.; Polak, A.; Ujma, M.; Kazienko, P. Emotion Recognition Using Wearables: A Systematic Literature Review—Work-in-progress. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), Austin, TX, USA, 23–27 March 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.W.; Vyzas, E.; Healey, J. Toward machine emotional intelligence: Analysis of affective physiological state. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2001, 23, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänsel, K.; Alomainy, A.; Haddadi, H. Large Scale Mood and Stress Self-Assessments on a Smartwatch; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Guimbretière, F.; Jung, M.F.; Khalid Choudhury, T. BoostMeUp: A Smartwatch App to Regulate Emotions and Improve Cognitive Performance. GetMobile Mob. Comput. Commun. 2020, 24, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, P.; Uusberg, A.; Culbertson, H.; Flory, R.; Uusberg, H.; Gross, J.J.; Marzullo, K.; Isbister, K. Emotion Regulation in the Wild: Introducing WEHAB System Architecture; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy Nadikattu, R. The Emerging Role of Artificial Intelligence in Modern Society. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2016, 4, 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.E.; Hong, S.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, N. Depression prediction by using ecological momentary assessment, actiwatch data, and machine learning: Observational study on older adults living alone. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e14149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocielnik, R.; Sidorova, N.; Maggi, F.M.; Ouwerkerk, M.; Westerink, J.H.D.M. Smart technologies for long-term stress monitoring at work. In Proceedings of the CBMS 2013—26th IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems, Porto, Portugal, 20–22 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home Assistant. Available online: https://www.home-assistant.io/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- ROS.org. ROS Navigation. 2020. Available online: http://wiki.ros.org/navigation (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- ROS.org. Setup and Configuration of the Navigation Stack on a Robot. 2018. Available online: http://wiki.ros.org/navigation/Tutorials/RobotSetup (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- ROS.org. Turtlebot Bringup. 2013. Available online: http://wiki.ros.org/turtlebot_bringup (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Healey, J.; Nachman, L.; Subramanian, S.; Shahabdeen, J.; Morris, M. Out of the lab and into the fray: Towards modeling emotion in everyday life. In Pervasive Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plarre, K.; Raij, A.; Hossain, S.M.; Ali, A.A.; Nakajima, M.; Al’Absi, M.; Ertin, E.; Kamarck, T.; Kumar, S.; Scott, M.; et al. Continuous inference of psychological stress from sensory measurements collected in the natural environment. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks, Chicago, IL, USA, 12–14 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zangróniz, R.; Martínez-Rodrigo, A.; Pastor, J.M.; López, M.T.; Fernández-Caballero, A. Electrodermal activity sensor for classification of calm/distress condition. Sensors 2017, 17, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecasteele, K.; Lázaro, J.; Cleeren, E.; Claes, K.; van Paesschen, W.; van Huffel, S.; Hunyadi, B. Artifact detection of wrist photoplethysmograph signals. In Proceedings of the BIOSIGNALS 2018—11th International Conference on Bio-Inspired Systems and Signal Processing, Funchal, Portugal, 19–21 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemzadeh, H.; Loseu, V.; Guenterberg, E.; Jafari, R. Sport training using body sensor networks: A statistical approach to measure wrist rotation for golf swing. In Proceedings of the BODYNETS 2009—4th International ICST Conference on Body Area Networks, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1–3 April 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Cui, L.; Liu, X.; Zhu, T. Emotion recognition based on customized smart bracelet with built-in accelerometer. PeerJ 2016, 2016, e2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjoreski, M.; Luštrek, M.; Gams, M.; Gjoreski, H. Monitoring stress with a wrist device using context. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 73, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramshur, J. Design, Evaluation, and Applicaion of Heart Rate Variability Analysis Software (HRVAS). Master’s Thesis, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Empatica Inc. Available online: https://www.empatica.com/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Pérez Fuentes, M.d.C.; Jesús Gázquez Linares, J.; Rubio, I.M.; Molero Jurado, M.d.M. Brief emotional intelligence inventory for senior citizens (EQ-i-M20). Psicothema 2014, 26, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-on, J.D.; Parker, R. Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version(BarOn EQ-i:YV), Technical Manual; MHS: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000; Volume 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Molero, M.d.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Mercader, I. Construction and Initial Validation of a Questionnaire to Assess Quality of Life in Older Institutionalized People. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2012, 2, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R. STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Self-Evaluation Questionnaire; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de la Iglesia, J.; Onís Vilches, M.C.; Dueñas Herrero, R.; Albert Colomer, C.; Aguado Taberné, C.; Luque Luque, R. Versión española del cuestionario de Yesavage abreviado (GDS) para el despistaje de depresión en mayores de 65 años: Adaptación y validación. MEDIFAM Rev. Med. Fam. Comunitaria 2002, 12, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.; Ezquerra, J.; Gómez Burgada, F.; Sala, J.M.; Seva Díaz, A. El miniexamen, cognoscitivo (un “test” sencillo, práctico, para detectar alteraciones intelectuales en pacientes médicos). Actas Luso-Esp. Neurol. Psiquiatr. Cienc. Afines 1979, 7, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg, B.; Ferris, S.H.; de Leon, M.J.; Crook, T. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. Studies of Illness in the Aged: The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C.; van Dierendonck, D. Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, R.; Páez, F. Estudio sobre la traducción al Español y las propiedades psicométricas de las escalas de Afecto Positivo y Negativo (PANAS). Salud Ment. 2003, 26, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Inventario de Personalidad NEO Revisado (NEO PI-R) e Inventario NEO Reducido de Cinco Factores (NEO-FFI). In Man. Prof.; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.J. LIBSVM: A Library for support vector machines. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2011, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likamwa, R.; Liu, Y.; Lane, N.D.; Zhong, L. MoodScope: Building a mood sensor from smartphone usage patterns. In Proceedings of the MobiSys 2013—11th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, Taipei, Taiwan, 25–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| General | Elements | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sensors | Smart home | Commercially available and self-built sensors for monitoring the user’s daily activity. |

| Empatica E4 | A medical device, such as an activity bracelet, for the acquisition of physiological signal data. | |

| Robotic Platform Sensors | Hokuyo UST-10LX LIDAR sensor for robot mapping and navigation. | |

| Set of proprioceptive sensors installed in the iClebo Kobuki base (bumpers, gyroscope...). | ||

| Control | Raspberry Pi | Computational node that executes the logic of the home automation section. It also serves as an integration node. |

| Intel NUC | Computational node that executes the logic of the integration software application. Artificial intelligence algorithms for coaching strategies. | |

| Intel NUC | Robot controller | |

| Actuator | Robotic Platform | A robotic system that will navigate autonomously through the house and interact with the user by providing them with coaching strategies. |

| Smart home | Elements such as shutter motors, lights and smart plugs. |

| Activity | Devices |

|---|---|

| Sleeping hours, physical activity, frequency of toilet visit | Activity wristband |

| Social interaction monitoring | Telephone call screening device (landline) or call logging services (mobile) |

| Drug consumption | Electronic pill dispenser |

| Proper nutrition | Fridge monitoring |

| Personal hygiene | Water flow detectors |

| Movement between rooms | Motion detectors and positioning system |

| Occupancy of armchairs/chairs | Pressure detectors |

| Bed occupancy | Load cells |

| Proper condition of the house | Temperature/Humidity sensor |

| TV viewing | Smart TV service integration |

| Opening of drawers, doors, windows... | Switch and windows/doors sensor |

| Use of household appliances | Power consumption sensors |

| Sensor Name | Model | Protocol | Description | Inc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mi Motion Sensor | YTC4041GL | Zigbee | PIR sensor from Xiaomi | Y |

| IKEA PIR Sensor | Zigbee | PIR sensor from IKEA | Y | |

| Temp/Hum Aqara | WSDCGQ11LM | Zigbee | Temperature/Humidity sensor from Aqara | Y |

| Mi Window/Door Sensor | YTC4039GL | Zigbee | Window/Door sensor from Xiaomi | Y |

| LIDL Window/Door sensor | TY0203 | Zigbee | Window/Door sensor from LIDL | Y |

| Heiman Gas Detector | HS1CG | Zigbee | Natural gas detector from Heiman | N |

| Aqara Leak Water Detector | SJCGQ11LM | Zigbee | Leak water detector from Aqara | N |

| Xiaomi Smoke Detector | JTYJ-GD-03MI/BB | Zigbee | Fire and smoke detector from Xiaomi | N |

| Smart Plug Xiaomi | ZNCZ04CM | Zigbee | Smart Plug from Xiaomi | Y |

| Smart Plug LIDL | HG06337 | Zigbee | Smart plug from LIDL | Y |

| Smart Bulb | LED1836G9 | Zigbee | Smart Bulb E27 806 lumens from IKEA. | Y |

| Sonoff POW | IM171130001 | WiFi | Consume monitoring fom Sonoff | N |

| Broadlink RM-Mini3 | RM-MINI3 | IR | Universal IR gateway | N |

| Robotic Platform Sensor | TURTLEBOT II | WiFi | Robotic base sensor, LIDAR Hokuyo UST-10LX and Orbecc Astra | Y |

| Flow Sensor | Own development | WiFi | Flow water sensor for kitchen and bathroom use. | N |

| Seat Sensor | Own development | WiFi | Sensor for monitoring the user’s time spent in a seated position | N |

| Bed Weight Sensor | Own development | WiFi | Sensor for monitoring user’s weight and time in bed | N |

| Large Consumption Sensor | Own development | WiFi | Sensor for high power consumption devices in the home. The PZEM-004T shall be used. | N |

| Thermocouple vitro/stove | Own development | WiFi | Sensor for monitoring the use of the cooker or hobs | N |

| Telephone Sensor | Own development | WiFi | Sensor to monitor social interaction via landline phone | N |

| Indoor Positioning System | Own development | WiFi | Indoor location system with decaWave | N |

| Breakfast | Bedroom | 08:00 |

| Bathroom | 08:05 | |

| Livingroom | 08:15 | |

| Kitchen | 08:17 | |

| Bathroom | 08:37 | |

| Livingroom | 08:45 | |

| Docking Station | 08:47 | |

| Snack | Livingroom | 11:30 |

| Kitchen | 11:33 | |

| Bathroom | 11:47 | |

| Livingroom | 12:00 | |

| Docking Station | 12:02 | |

| Lunch | Livingroom | 13:30 |

| Kitchen | 13:33 | |

| Bathroom | 14:00 | |

| Livingroom | 14:10 | |

| Docking Station | 14:12 | |

| Afternoon Snack | Livingroom | 17:30 |

| Kitchen | 17:32 | |

| Bathroom | 17:47 | |

| Livingroom | 17:57 | |

| Docking Station | 18:00 | |

| Dinner | Livingroom | 20:30 |

| Kitchen | 20:33 | |

| Bathroom | 21:02 | |

| Livingroom | 21:10 | |

| Docking Station | 21:12 | |

| Sleep | Livingroom | 22:30 |

| Bedroom | 22:32 | |

| Bathroom | 22:35 | |

| Bedroom | 22:45 | |

| Docking Station | 22:47 |

| Signal | E4 Built-In Sensor | Range | Resolution Sample Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer | 3-axis accelerometer | −2 g +2 g | 8 bit 32 Hz |

| Temperature | Infrared thermopile | −40 ° +115 °C | 14 bit 0.02 °C 4 Hz |

| Electrodermal Activity | AC Current source 100 uA @ 8 Hz/100 uSiemens | 0.01 µSiemens 100 µSiemens | 14 bit 900 pSiemens 4 Hz |

| Heart Rate | Photoplethysmography Blood Volume Pulse 4 LEDs (2 × Green, 2 × Red) 2 PhotodiodesTotal 15.5 mm2 sensitve area. | 0.9 nW 64 Hz |

| Signal | Filtering |

|---|---|

| Accelerometer | Band-pass filter (0.2 Hz–10 Hz) 3rd order Butterworth |

| Temperature | Threshold @ 2 °C |

| Electrodermal Activity | Low-pass filter (0–1.5 Hz) 3rd order Butterworth EDA, SCLR and SCR Extraction [99] |

| Heart Rate | HR resampled at 1 Hz Normalized to first 10 min/day [10] |

| Domain | Measurement | Features | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Maximum value of the rectified segment | MAX | 4 | [100] |

| 90th percentile of the rectified segment | P90 | 4 | ||

| Variance of the segment | VAR | 4 | ||

| Mean Absolute Deviation of the segment | MAD | 4 | ||

| Norm of the segment | Norm | 4 | ||

| Different between maximum amplitude and mean of signal segment | AMP | 4 | [101] | |

| Minimum value of signal segment | MIN | 4 | ||

| Standard deviation of signal segment | STD | 4 | ||

| Root Mean Square of signal segment | RMS | 4 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVFD | 4 | [85] | |

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVFDN | 4 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVSD | 4 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVSDN | 4 | ||

| Frequency | Mean value of Power Spectral Density | FM | 4 | [102] |

| Standard deviation of Power Spectral Density | FSTD | 4 | ||

| 25-percentile of Power Spectral Density | FP25 | 4 | [10] | |

| 50-percentile of Power Spectral Density | FP50 | 4 | ||

| 75-percentile of Power Spectral Density | FP75 | 4 | ||

| Domain | Measurement | Features | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Mean temperature of the segment | MT | 1 | [103] |

| Slope of a fitted regression line of the segment | SRL | 1 | ||

| Intercept of a fitted regression line of the segment | IRL | 1 | ||

| Standard deviation of signal segment | STD | 1 | [101] | |

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVFD | 1 | [85] | |

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVFDN | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVSD | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVSDN | 1 | ||

| Frequency | Mean value of Power Spectral Density (PSD) | FM | 1 | [102] |

| Standard deviation of Power Spectral Density (PSD) | FSTD | 1 | ||

| 25-percentile of Power Spectral Density (PSD) | FP25 | 1 | [10] | |

| 50-percentile of Power Spectral Density (PSD) | FP50 | 1 | ||

| 75-percentile of Power Spectral Density (PSD) | FP75 | 1 | ||

| Domain | Measurement | Features | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Maximum value of the rectified segment | MAXHR | 1 | [100] |

| 90th percentile of the rectified segment | P90HR | 1 | ||

| Variance of the segment | VARHR | 1 | ||

| Mean Absolute Deviation of the segment | MADHR | 1 | ||

| Norm of the segment | normHR | 1 | ||

| Mean value of signal segment | Mean | 1 | [101] | |

| Minimum value of signal segment | MIN | 1 | ||

| Standard deviation of signal segment | STD | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVFD | 1 | [85] | |

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVFDN | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVSD | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVSDN | 1 | ||

| Mean of the Smooth HR | SM | 1 | ||

| Mean of the First Differences | MFD | 1 | ||

| Frequency | Very Low Absolute Spectral Power | aVLF | 1 | [104] |

| Low Absolute Spectral Power | aLF | 1 | ||

| High Absolute Spectral Power | aHF | 1 | ||

| Total Absolute Spectral Power | aTotal | 1 | ||

| Very Low Frequency Spectral Power in Percentage | pVLF | 1 | ||

| Low Frequency Spectral Power in Percentage | pLF | 1 | ||

| High Frequency Spectral Power in Percentage | pHF | 1 | ||

| Low Frequency Spectral Power Normalize to Total Power | nLF | 1 | ||

| High Frequency Spectral Power Normalize to Total Power | nHF | 1 | ||

| Ratio of Low Frequency to High Frequency | LFHF | 1 | ||

| Very Low Frequency Peak | peakVLF | 1 | ||

| Low Frequency Peak | peakLF | 1 | ||

| High Frequency Peak | peakHF | 1 | ||

| Domain | Measurement | Features | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Mean | MSC | 3 | [99] |

| Standard deviation | SDSC | 3 | ||

| Maximum | MASC | 3 | ||

| Minimum | MISC | 3 | ||

| Dynamic range | DRSC | 3 | ||

| Mean of the first derivative | FMSC | 3 | ||

| Standard deviation of the first derivative | FDSC | 3 | ||

| Mean of the second derivative | SMSC | 3 | ||

| Standard deviation of the second derivative | SDSC | 3 | ||

| Arc length | ALSC | 3 | ||

| Integral | INSC | 3 | ||

| Normalized average power | APSC | 3 | ||

| Normalized root mean square | RMSC | 3 | ||

| Area-perimeter | ILSC | 3 | ||

| Energy-perimeter | ELSC | 3 | ||

| High order skewness | SKSC | 3 | ||

| High order kurtosis | KUSC | 3 | ||

| Central moment | MOSC | 3 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVFD | 1 | [85] | |

| Means of the Absolute Values of the First Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVFDN | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the raw signal segment | MAVSD | 1 | ||

| Means of the Absolute Values of the Second Differences of the normalized signal segment | MAVSDN | 1 | ||

| Frequency | Spectral power in bandwidths 0.1 to 0.2 | F1SC | 3 | [99] |

| Spectral power in bandwidths 0.2 to 0.3 | F2SC | 3 | ||

| Spectral power in bandwidths 0.3 to 0.4 | F3SC | 3 | ||

| Mean value of Power Spectral | FMSCR | 3 | [102] | |

| Standard deviation of Power Spectral Density | FSTDSCR | 3 | ||

| 25-percentile of Power Spectral Density | FP25 | 3 | [10] | |

| 50-percentile of Power Spectral Density | FP50 | 3 | ||

| 75-percentile of Power Spectral Density | FP75 | 3 | ||

| Information | Description |

|---|---|

| Happiness level | Representation of the happiness level felt by the user at the time of the test on a discrete scale divided into 5 levels (0–4). |

| Activity level | Representation of the activity level felt by the user at the time of the test on a discrete scale divided into 5 levels (0–4). |

| Test hours | User-defined time register of time tests. |

| Reaction time | Timestamp at which the application notifies that the test is to be performed and timestamp at which the user accesses the notification. |

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67 | 55 | 60 | 63 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| Days | 9 | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| Non-valid days | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Total EMAs (Daily avg.) | 42 (4.67 ± 0.67) | 57 (3.8 ± 0.75) | 64 (5.33 ± 1.84) | 46 (3.54 ± 0.93) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calatrava-Nicolás, F.M.; Gutiérrez-Maestro, E.; Bautista-Salinas, D.; Ortiz, F.J.; González, J.R.; Vera-Repullo, J.A.; Jiménez-Buendía, M.; Méndez, I.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; Mozos, O.M. Robotic-Based Well-Being Monitoring and Coaching System for the Elderly in Their Daily Activities. Sensors 2021, 21, 6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21206865

Calatrava-Nicolás FM, Gutiérrez-Maestro E, Bautista-Salinas D, Ortiz FJ, González JR, Vera-Repullo JA, Jiménez-Buendía M, Méndez I, Ruiz-Esteban C, Mozos OM. Robotic-Based Well-Being Monitoring and Coaching System for the Elderly in Their Daily Activities. Sensors. 2021; 21(20):6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21206865

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalatrava-Nicolás, Francisco M., Eduardo Gutiérrez-Maestro, Daniel Bautista-Salinas, Francisco J. Ortiz, Joaquín Roca González, José Alfonso Vera-Repullo, Manuel Jiménez-Buendía, Inmaculada Méndez, Cecilia Ruiz-Esteban, and Oscar Martínez Mozos. 2021. "Robotic-Based Well-Being Monitoring and Coaching System for the Elderly in Their Daily Activities" Sensors 21, no. 20: 6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21206865

APA StyleCalatrava-Nicolás, F. M., Gutiérrez-Maestro, E., Bautista-Salinas, D., Ortiz, F. J., González, J. R., Vera-Repullo, J. A., Jiménez-Buendía, M., Méndez, I., Ruiz-Esteban, C., & Mozos, O. M. (2021). Robotic-Based Well-Being Monitoring and Coaching System for the Elderly in Their Daily Activities. Sensors, 21(20), 6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21206865