Model-Based Position and Reflectivity Estimation of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Arrays

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

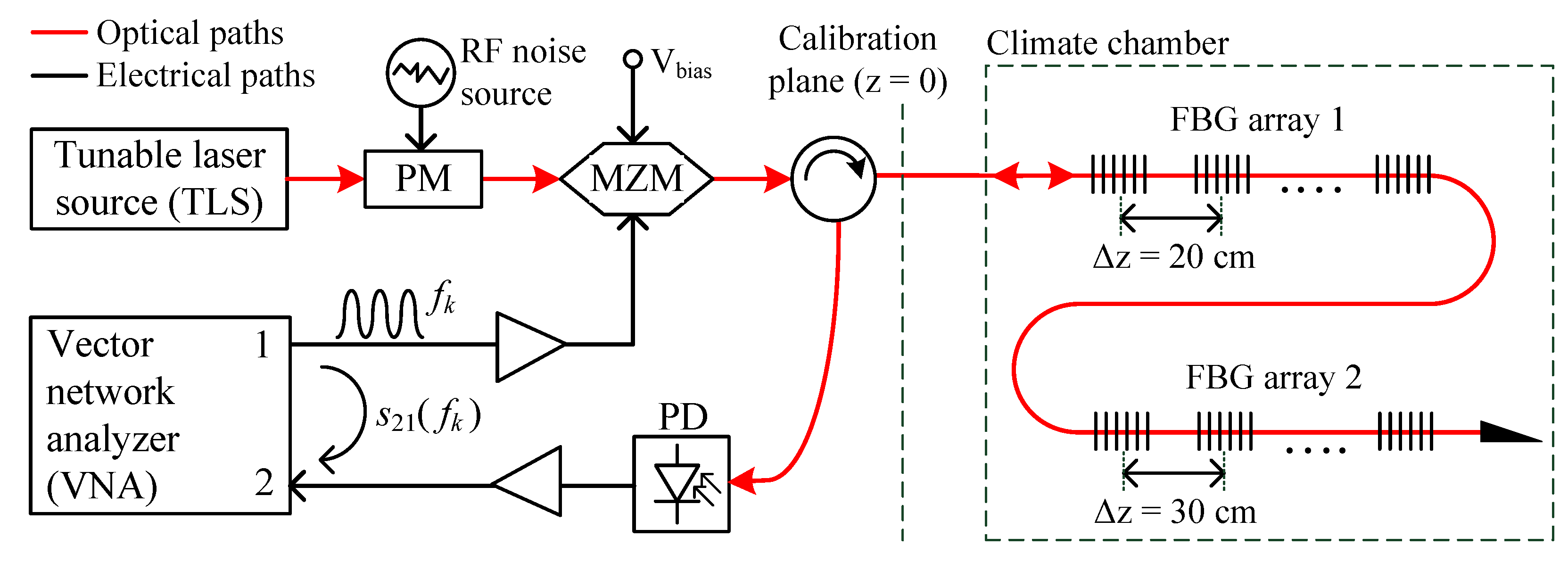

2.1. Measurement Principle and Setup

2.2. Model-Based Estimation

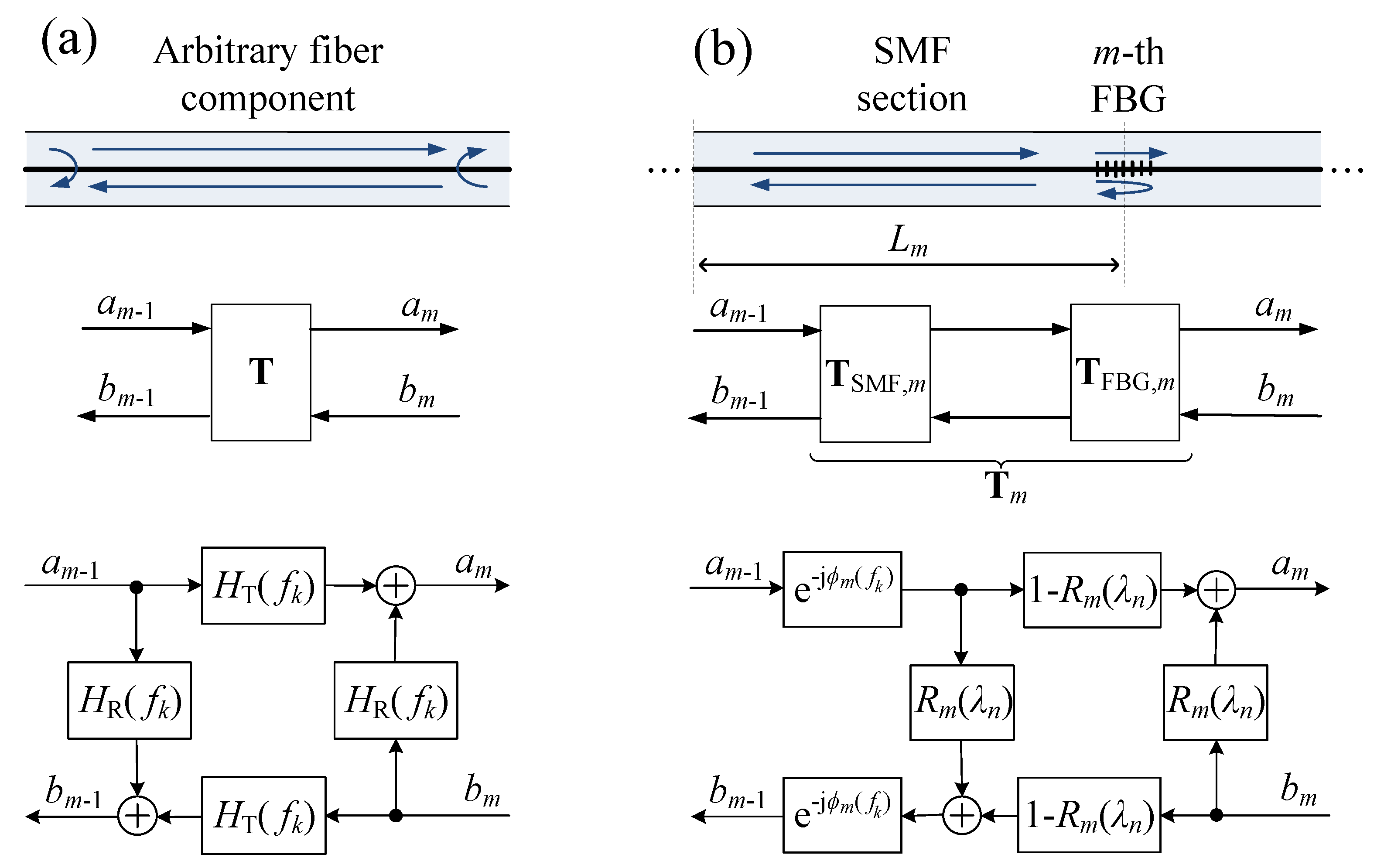

2.2.1. Transfer Matrix Model

- All fiber-optic components are reciprocal and fulfill the requirements of linear and time-invariant systems.

- Typically, the length of a grating in an FBG array is in the order of some millimeters, and the peak reflectivities are well below 5% to minimize interferences by crosstalk and power depletion [25]. As the spatial resolution of the iOFDR measurement system is in the range of centimeters and the group delay of a weakly-reflecting grating is very small, the gratings are modeled as wavelength-dependent point reflectors with reflectivity in good approximation.

- Any losses of the gratings due to scattering or coupling to cladding modes are neglected, so that the transmitted and reflected power equals 100% of the incident light. This leads to a simplified FBG transfer matrix of:

- For short fiber lengths, attenuation and dispersion effects are negligible, so that the optical fiber behaves like an allpass, introducing just a phase shift due to the propagation delay. Furthermore, the weak Rayleigh backscattering in the fiber can usually be neglected, resulting in a diagonal transfer matrix for modeling a short SMF section:

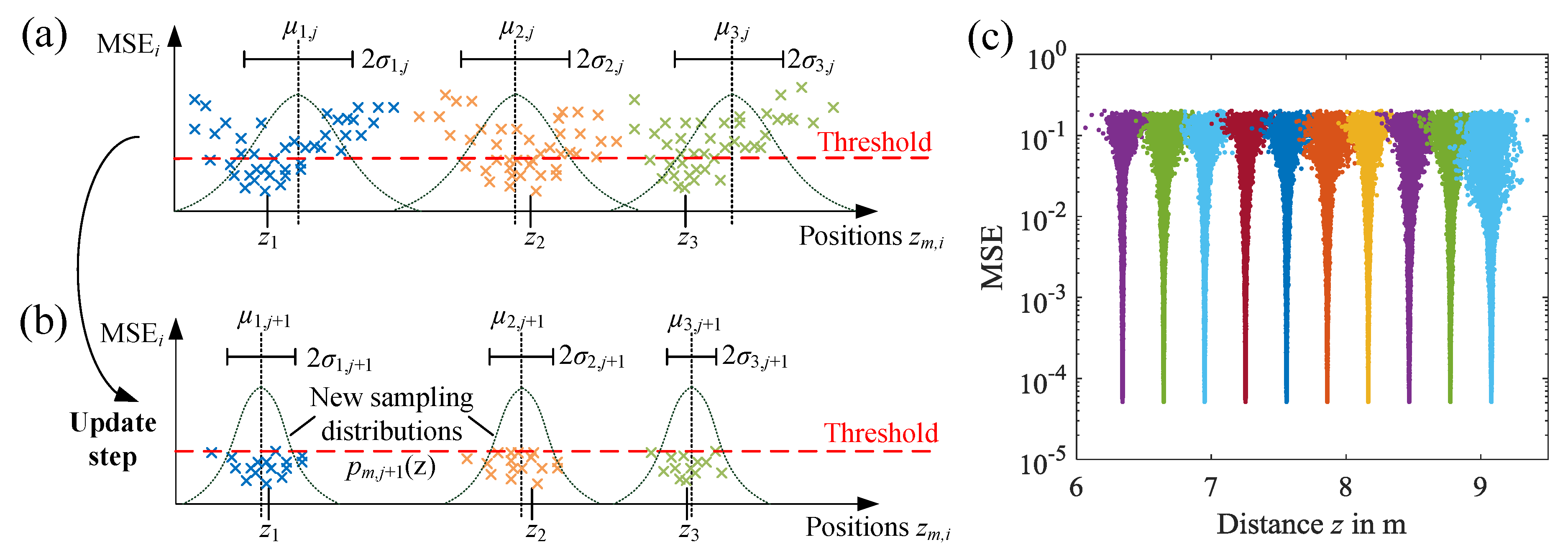

2.2.2. Position Estimation Method

| Algorithm 1 Position estimation. |

|

2.2.3. Reflectivity Estimation with TMM

2.3. Algorithm Evaluation with Monte Carlo Simulations

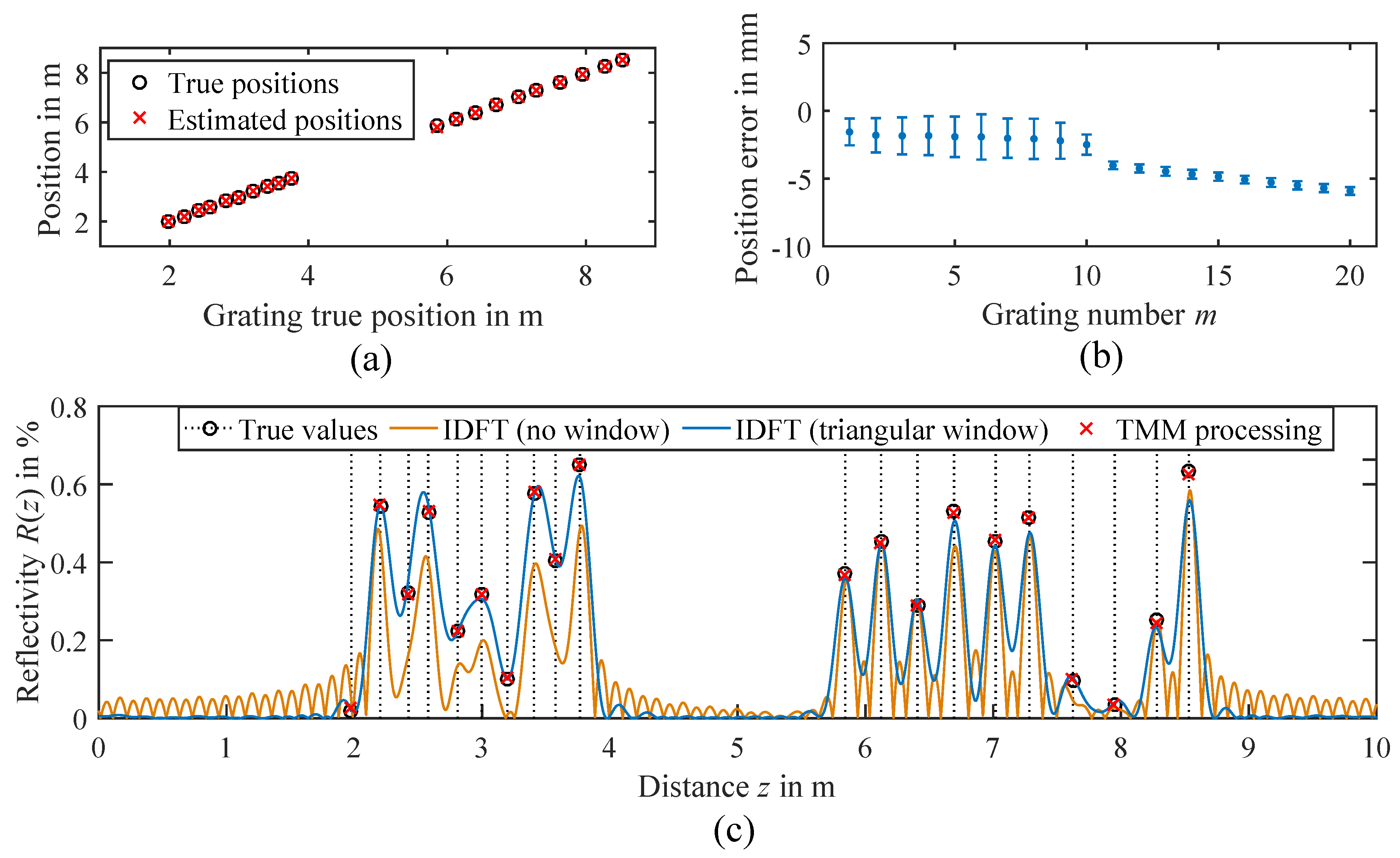

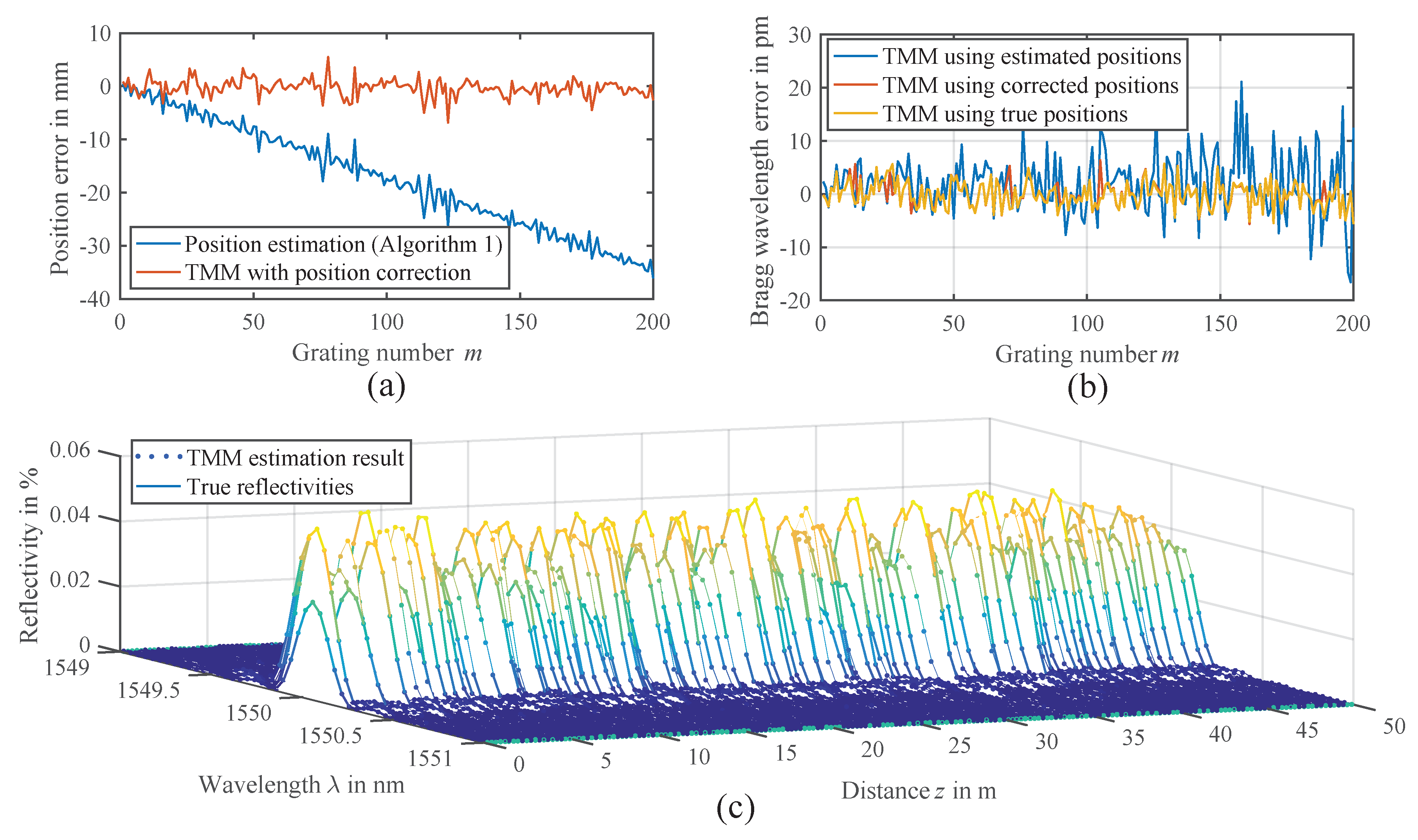

2.3.1. Evaluation of Position Estimation

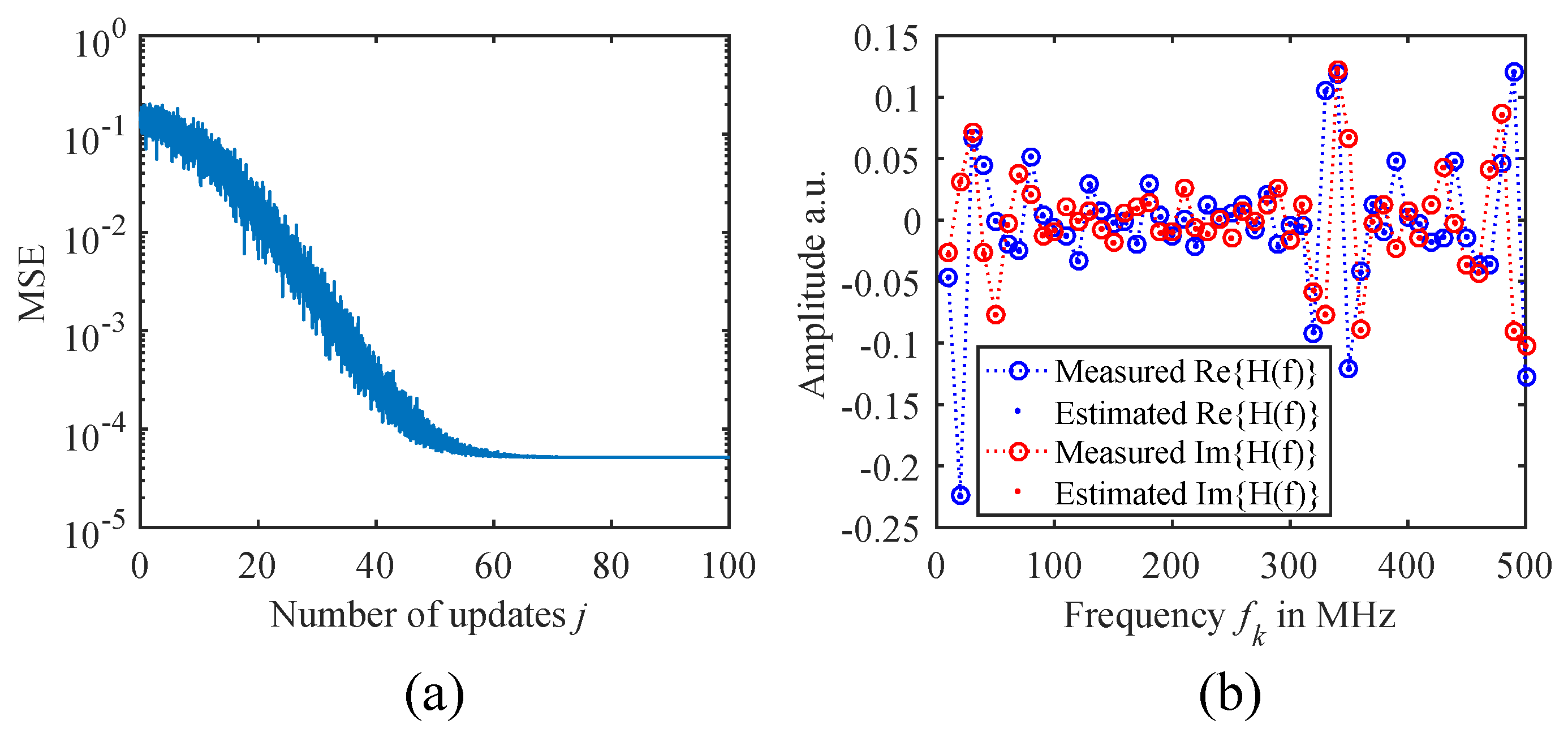

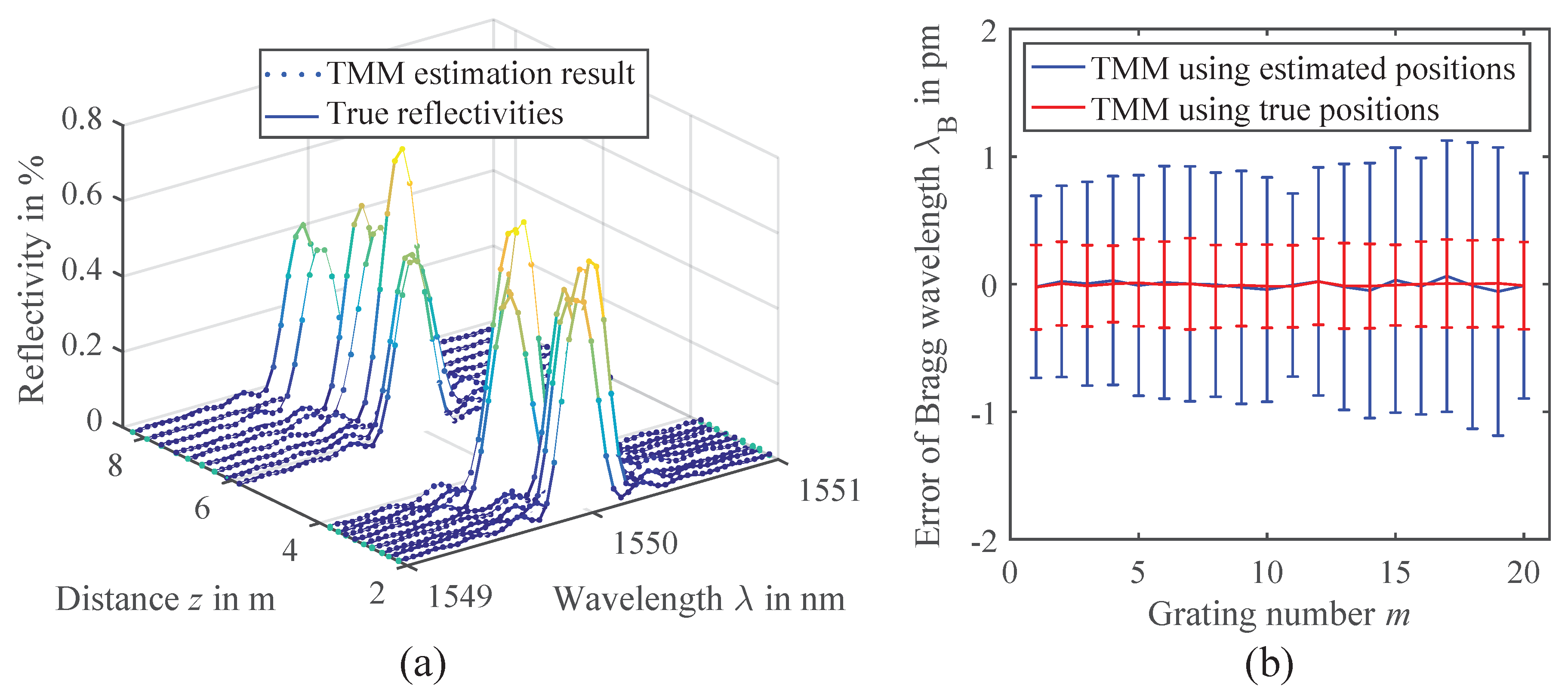

2.3.2. Evaluation of Reflectivity Estimation Using TMM

2.3.3. Evaluation of Bragg Wavelength Errors

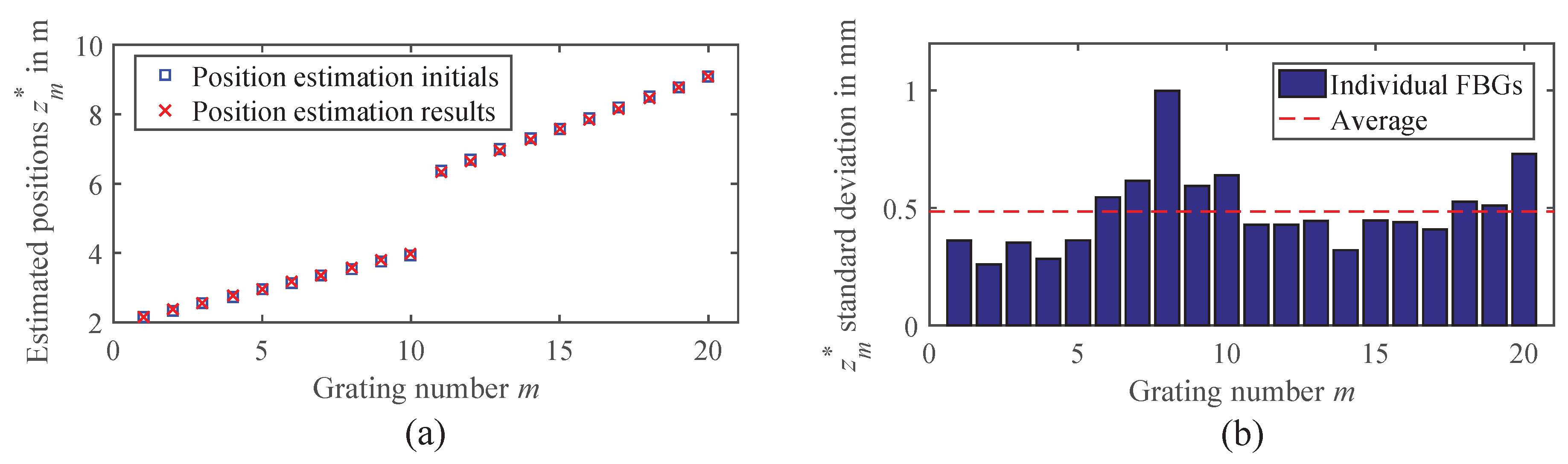

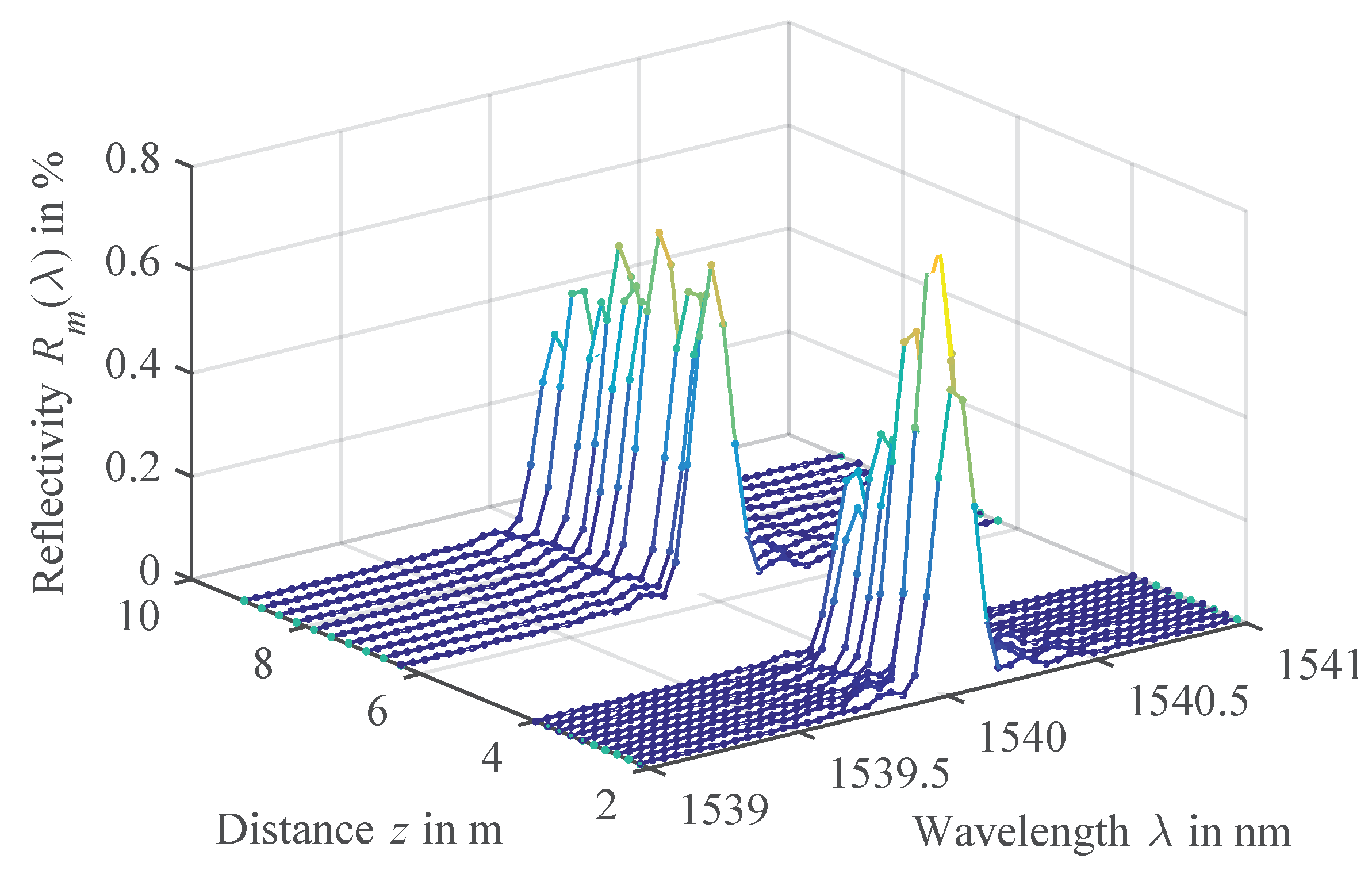

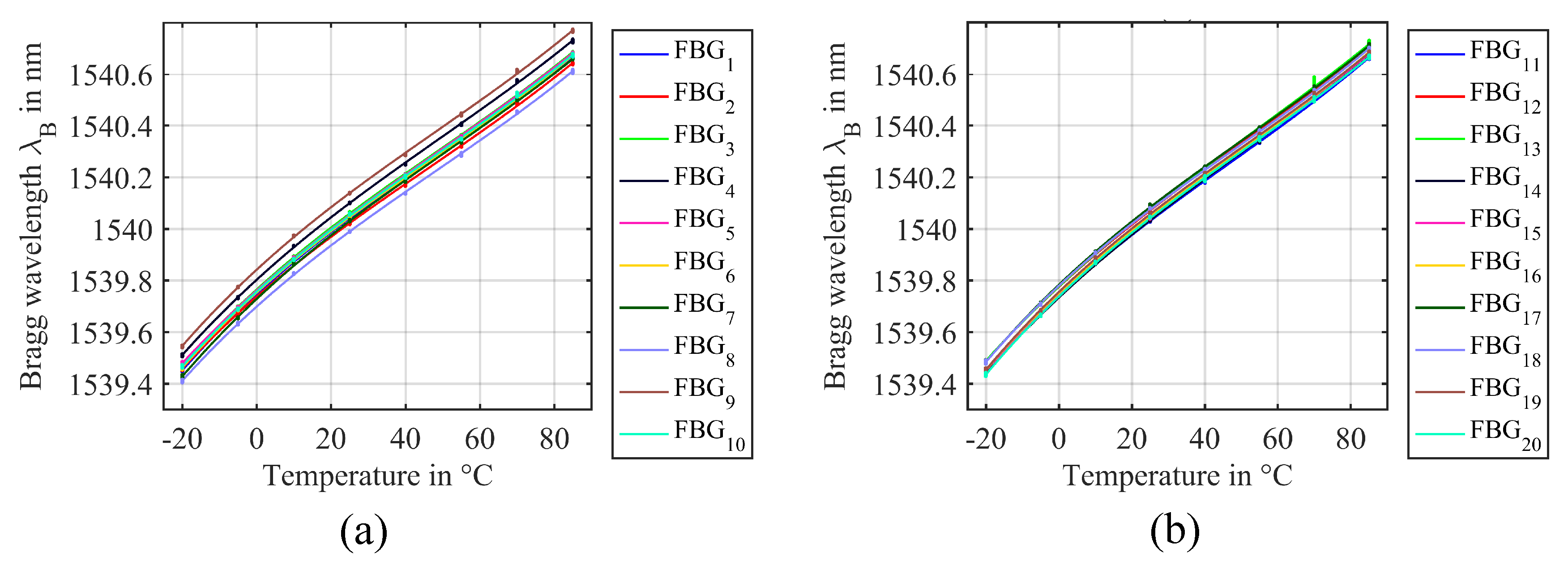

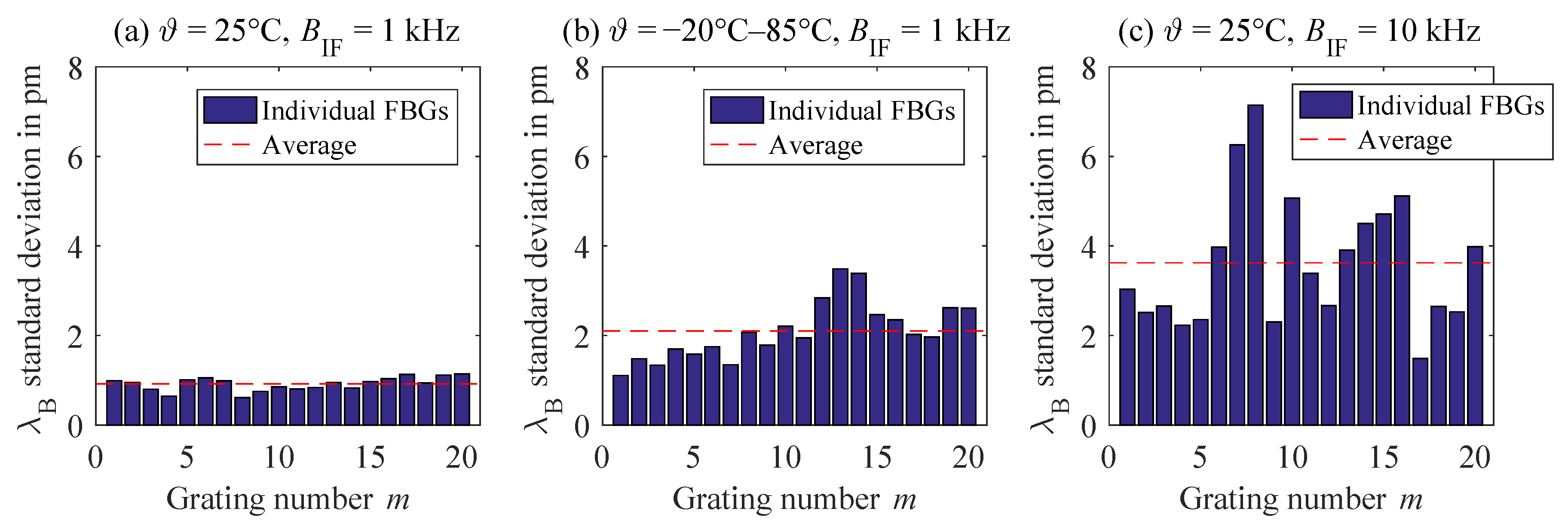

3. Experimental Results

4. Discussion

- An FBG array can be modeled using a sparse set of parameters (e.g., reflectivities and positions), so only a small number of parameters needs to be estimated. Priorly known or estimated parameters (e.g., grating positions) can be included in the models so that the number of estimation parameters reduces even further, saving computational time.

- The drawbacks of IDFT processing associated with windowing can be avoided as the parameters are directly estimated in the frequency domain.

- The modulation frequencies are not bound to an equidistant grid as required for IDFT processing, but could be chosen irregularly or randomly, instead.

- Systematic errors due to crosstalk by multiple reflections and spectral shadowing between gratings at the same wavelength can be mitigated using the TMM, as it considers the forward and backward propagation of the modulation signal.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Ding, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, K.; Jiang, J.; Yang, D.; Pan, G.; Pu, Z.; Liu, T. Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors Based on Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisov, A.; Soto, M.A.; Thévenaz, L. Going beyond 1000000 resolved points in a Brillouin distributed fiber sensor: Theoretical analysis and experimental demonstration. Light Sci. Appl. 2016, 5, e16074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrias, A.; Casas, J.R.; Villalba, S. A Review of Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors for Civil Engineering Applications. Sensors 2016, 16, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Chen, L. Recent Progress in Distributed Fiber Optic Sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 8601–8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, M.A.; Bolognini, G.; Pasquale, F.D. Analysis of optical pulse coding in spontaneous Brillouin-based distributed temperature sensors. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 19097–19111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.D. Using simplex codes to improve OTDR sensitivity. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 1993, 5, 822–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werzinger, S.; Bergdolt, S.; Engelbrecht, R.; Thiel, T.; Schmauss, B. Quasi-Distributed Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Using Stepped Incoherent Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry. IEEE J. Lightwave Technol. 2016, 34, 5270–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soller, B.J.; Gifford, D.K.; Wolfe, M.S.; Froggatt, M.E. High resolution optical frequency domain reflectometry for characterization of components and assemblies. Opt. Express 2005, 13, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamehmedovic, E.; Glombitza, U. Fiber optic distributed temperature sensor using incoherent optical frequency domain reflectometry. In Proceedings of the Emerging Optoelectronic Applications, San Jose, CA, USA, 25 June 2004; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M.K.; Raju, S.D.V.S.J.; Arya, R.; Ravindranath, S.; Kher, S.; Oa, S. Raman optical fiber distributed temperature sensor using wavelet transform based simplified signal processing of Raman backscattered signals. Opt. Laser Technol. 2015, 65, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, M.A.; Wylie, M.T.V.; Castillo-Guerra, E.; Colpitts, B.G. Reduction in the Number of Averages Required in BOTDA Sensors Using Wavelet Denoising Techniques. J. Lightwave Technol. 2012, 30, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.A.; Ramírez, J.A.; Thévenaz, L. Intensifying the response of distributed optical fibre sensors using 2D and 3D image restoration. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejedor, J.; Macias-Guarasa, J.; Martins, H.F.; Pastor-Graells, J.; Corredera, P.; Martin-Lopez, S. Machine Learning Methods for Pipeline Surveillance Systems Based on Distributed Acoustic Sensing: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candy, J.V. Model-Based Signal Processing, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Werzinger, S.; Gottinger, M.; Gussner, S.; Bergdolt, S.; Engelbrecht, R.; Schmauss, B. Model-based compressed sensing of fiber Bragg grating arrays in the frequency domain. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Jeju, Korea, 24–28 April 2017; pp. 103236H-1–103236H-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kersey, A.D.; Davis, M.A.; Patrick, H.J.; LeBlanc, M.; Koo, K.P.; Askins, C.G.; Putnam, M.A.; Friebele, E.J. Fiber grating sensors. IEEE J. Lightwwve Technol. 1997, 15, 1442–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.J. In-fibre Bragg grating sensors. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1997, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavaioli, F.; Baldini, F.; Tombelli, S.; Trono, C.; Giannetti, A. Biosensing with optical fiber gratings. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, R. Fiber Bragg Gratings, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, W.W.; Dunphy, J.R.; Meltz, G. Multiplexing fiber Bragg grating sensors. Fiber Integr. Opt. 1991, 10, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.F.; Coroy, T.; Smith, P.W.E. Time-division multiplexing of large serial fiber-optic Bragg grating sensor arrays. Appl. Opt. 2001, 40, 2643–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Bai, W.; Guo, H.; Wen, H.; Yu, H.; Jiang, D. Huge capacity fiber-optic sensing network based on ultra-weak draw tower gratings. Photonic Sens. 2016, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wen, H.; Guo, H.; Yang, M. A time- and wavelength-division multiplexing sensor network with ultra-weak fiber Bragg gratings. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 22799–22807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, F.J. On the use of windows for harmonic analysis with the discrete Fourier transform. Proc. IEEE 1978, 66, 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Qian, L.; Zhou, C.; Zheng, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, R.; Jiang, D. Crosstalk and ghost gratings in a large-scale weak fiber Bragg grating array. IEEE J. Lightwwve Technol. 2017, 35, 2032–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R.I. Frequency domain optical reflectometer. Appl. Opt. 1981, 20, 1840–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uttam, D.; Culshaw, B. Precision time domain reflectometry in optical fiber systems using a frequency modulated continuous wave ranging technique. IEEE J. Lightwwve Technol. 1985, 3, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori-Shiraz, H.; Okoshi, T. Optical frequency-domain reflectometery. Opt. Quant. Electron. 1986, 18, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, J.; Iizuka, K.; Nielsen, J. Optical fiber fault locator by the step frequency method. Appl. Opt. 1987, 26, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeppel, M.; Werzinger, S.; Ringel, T.; Bechtold, P.; Thiel, T.; Engelbrecht, R.; Bosselmann, T.; Schmauss, B. Combined distributed Raman and Bragg fiber temperature sensing using incoherent optical frequency domain reflectometry. J. Sens. Sens. Syst. 2018, 7, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liehr, S.; Krebber, K. Application of Quasi-Distributed and Dynamic Length and Power Change Measurement Using Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry. IEEE Sens. J. 2012, 12, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnoski, M.K.; Rourke, M.D.; Jensen, S.M.; Melville, R.T. Optical time domain reflectometer. Appl. Opt. 1977, 16, 2375–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Personick, S.D. Photon Probe—An Optical-Fiber Time-Domain Reflectometer. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1977, 56, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K.; Freundorfer, A.P.; Wu, K.H.; Mori, H.; Ogura, H.; Nguyen, V.K. Step-frequency radar. J. Appl. Phys. 1984, 56, 2572–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, T. Fiber grating spectra. J. Lightwave Technol. 1997, 15, 1277–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yariv, A. Coupled-mode theory for guided-wave optics. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1973, 9, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrañaga, P.; Lozano, J.A. (Eds.) Estimation of Distribution Algorithms; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild, M.; Pelikan, M. An introduction and survey of estimation of distribution algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2011, 1, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, D. Review and Analysis of Peak Tracking Techniques for Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value ± Tolerance a | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of FBGs | M | 20 | – |

| Bragg wavelengths | 1550 ± 0.1 | nm | |

| FBG spectral bandwidth (FWHM) | 200 ± 20 | pm | |

| FBG peak reflectivities | 0.5 ± 0.1 | % | |

| FBG positions | 2.0, 2.2, …, 3.8 ± 0.02 | m | |

| FBG positions | 5.8, 6.1, …, 8.5 ± 0.03 | ||

| Number of simulation runs | 1000 | – | |

| Modulation frequencies | 10 …500 | MHz | |

| Modulation frequency steps | 10 | MHz | |

| Measurement wavelengths | 1549…1551 | nm | |

| Measurement wavelength steps | 40 | pm | |

| Additional Gaussian noise (RMS) | – | ||

| Fiber group refractive index | 1.447 | – | |

| Fiber attenuation coefficient | 0.25 | dB/km |

| Parameter | Symbol | Values | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement temperature range | T | −20…85 | C |

| Measurement temperature steps | 15 | K | |

| Number of measurements per temperature | 100 | – | |

| Modulation frequencies | 10 …500 | MHz | |

| Modulation frequency steps | 10 | MHz | |

| VNA intermediate frequency bandwidth | 1 | kHz | |

| Measurement wavelengths | 1539…1541 | nm | |

| Measurement wavelength steps | 40 | pm | |

| Average fiber coupled optical power | −5 | dBm | |

| Fiber group refractive index | 1.447 | – | |

| Fiber attenuation coefficient | 0.25 | dB/km |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Werzinger, S.; Zibar, D.; Köppel, M.; Schmauss, B. Model-Based Position and Reflectivity Estimation of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Arrays. Sensors 2018, 18, 2268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072268

Werzinger S, Zibar D, Köppel M, Schmauss B. Model-Based Position and Reflectivity Estimation of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Arrays. Sensors. 2018; 18(7):2268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072268

Chicago/Turabian StyleWerzinger, Stefan, Darko Zibar, Max Köppel, and Bernhard Schmauss. 2018. "Model-Based Position and Reflectivity Estimation of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Arrays" Sensors 18, no. 7: 2268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072268

APA StyleWerzinger, S., Zibar, D., Köppel, M., & Schmauss, B. (2018). Model-Based Position and Reflectivity Estimation of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Arrays. Sensors, 18(7), 2268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072268