Positive Diagnosis of Ancient Leprosy and Tuberculosis Using Ancient DNA and Lipid Biomarkers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Extraction of Microbial aDNA

2.2. PCR Amplification

2.3. Diversity at Multiple Locus Variable Nucleotide Tandem Repeats (VNTRs)

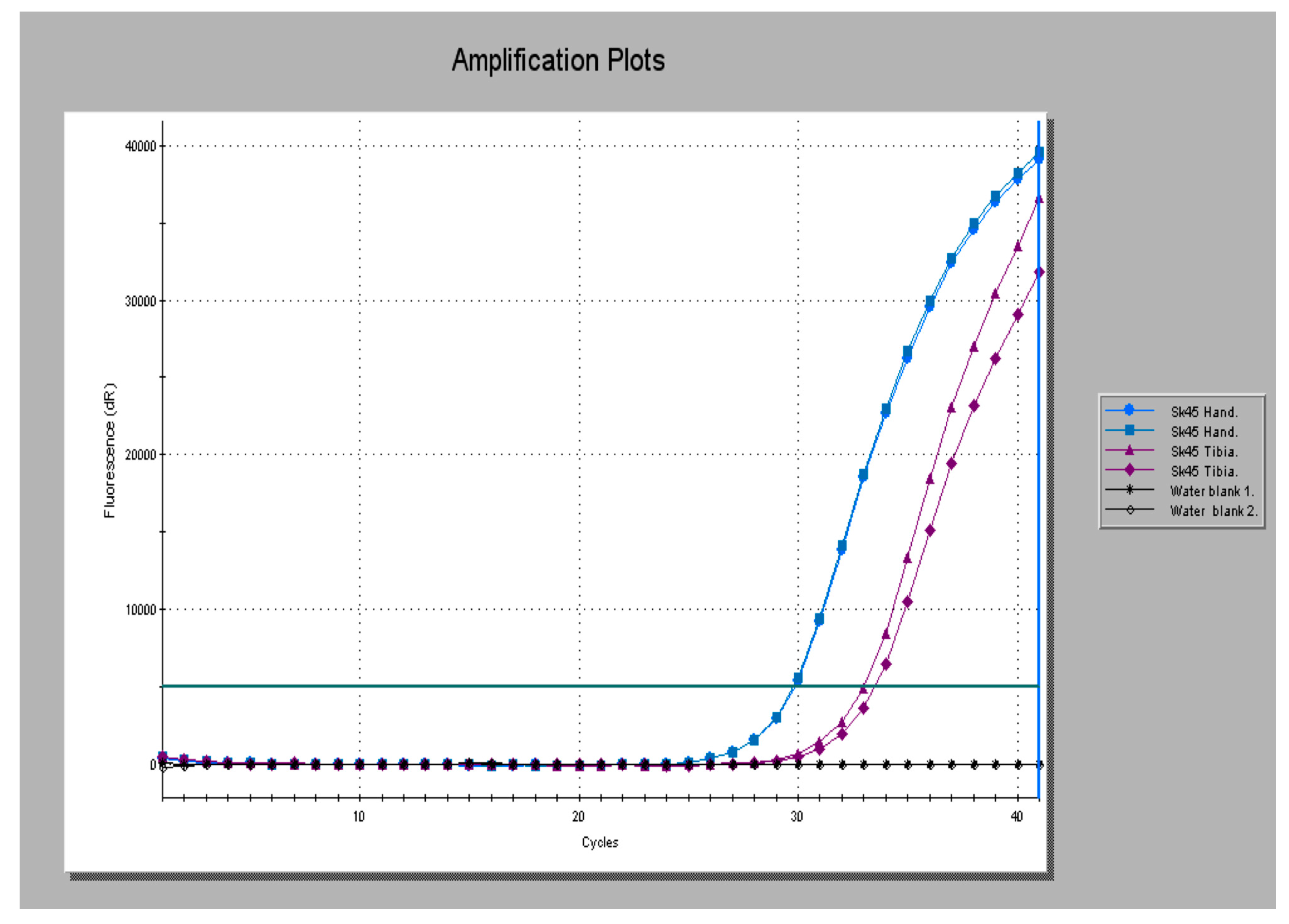

2.4. Validation and the Use of Real Time Platforms

2.5. Benefits of Real Time Platforms

2.5.1. Optimization

2.5.2. Reproducibility

2.5.3. Control Amplifications

2.5.4. Assessing Inhibition

2.5.5. Validation

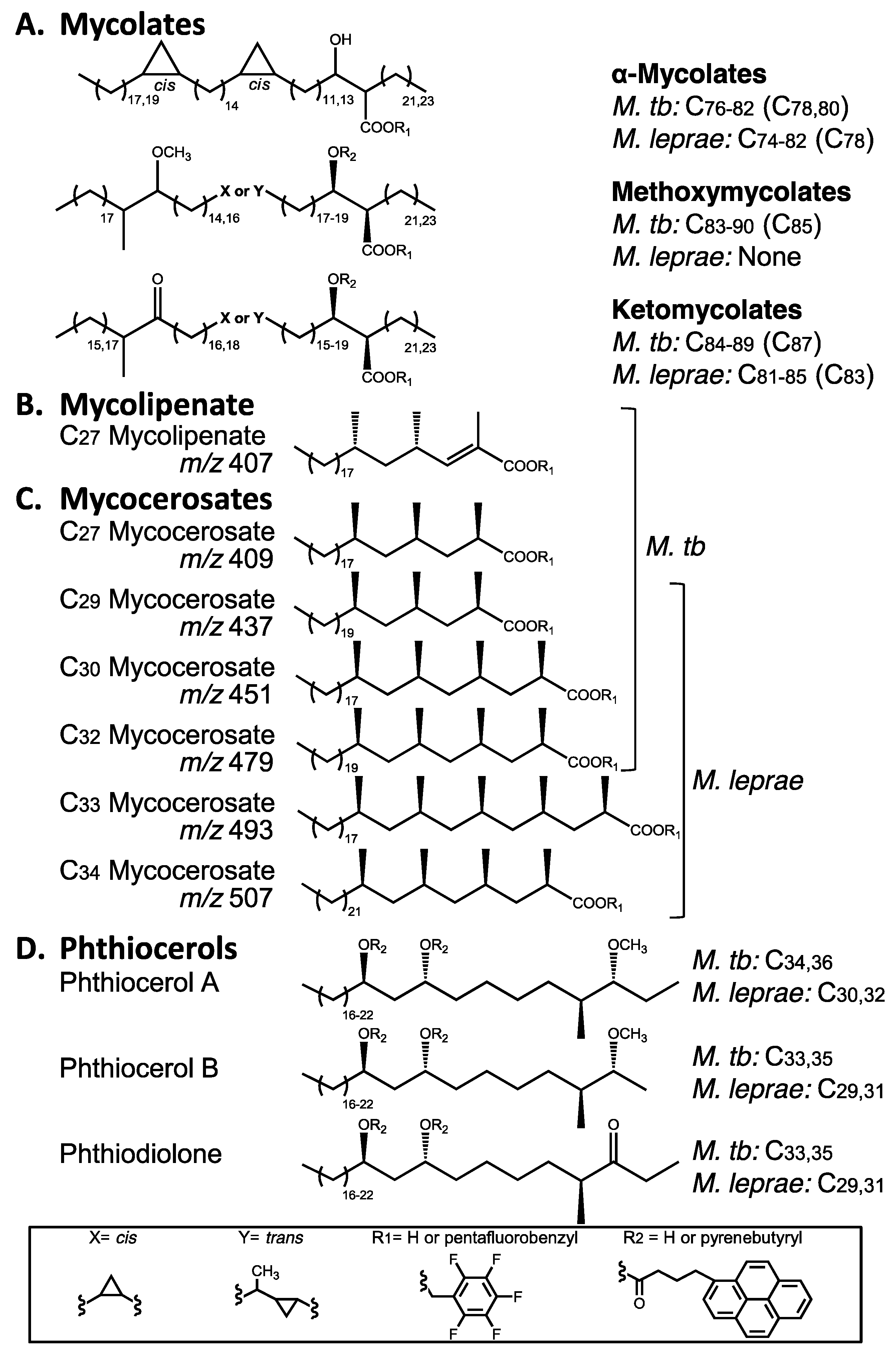

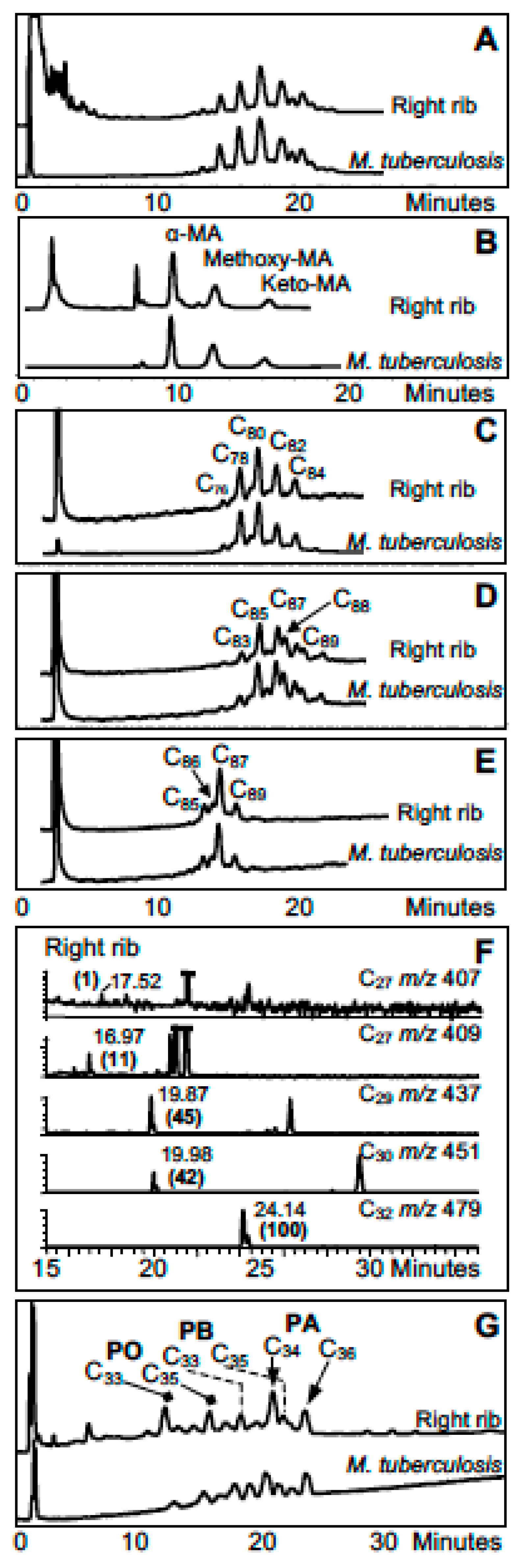

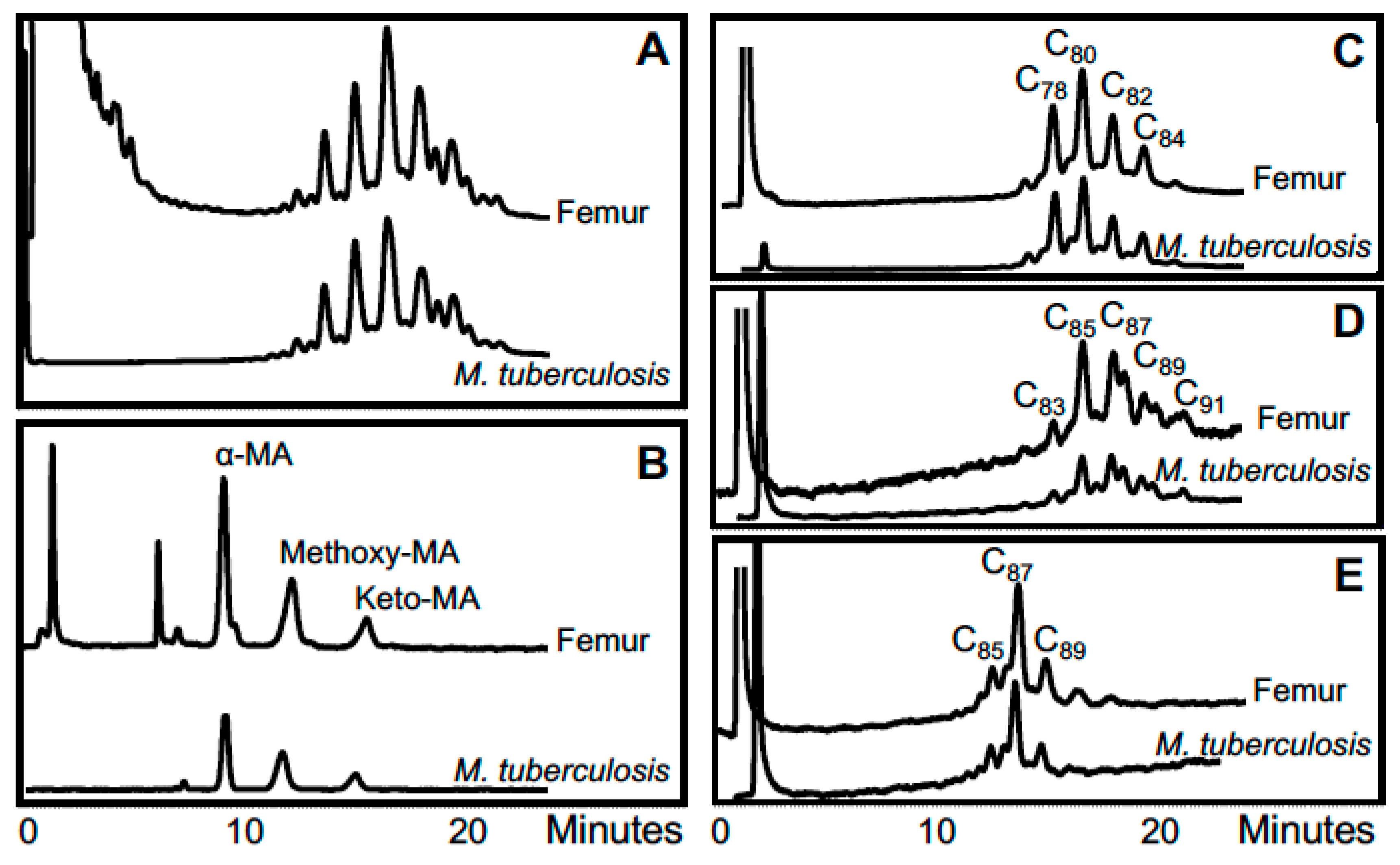

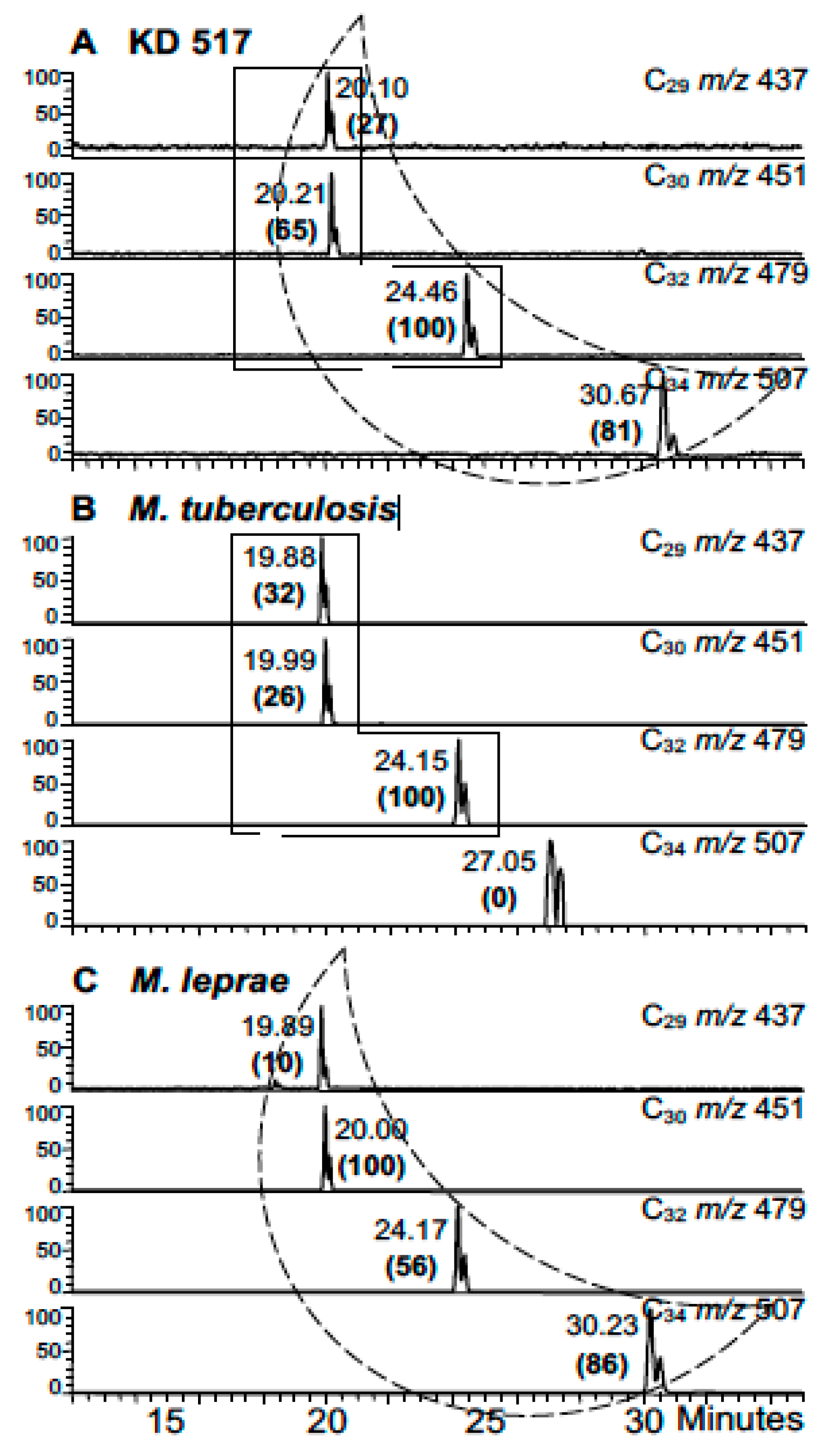

3. Mycobacterial Lipid Biomarkers

3.1. Extraction of Mycobacterial Cell Wall Lipids

3.2. Combined Biomarker Diagnoses—aDNA and Bacterial Cell Wall Lipids

4. The Authenticity and Validity of aDNA and Lipid Biomarkers for Ancient Tuberculosis and Leprosy

- (1)

- “rate heterogeneity or horizontal gene transfer is obscuring our dating analysis, perhaps as a result of human population expansions which increase the availability of susceptible hosts and allow selection to operate more quickly,

- (2)

- the pathogens identified in the earlier archaeological material are in fact not members of the MTBC, but rather are ancestral forms that have since undergone replacements, or

- (3)

- certain techniques for MTBC identification in archaeological material lack specificity.”

- (1)

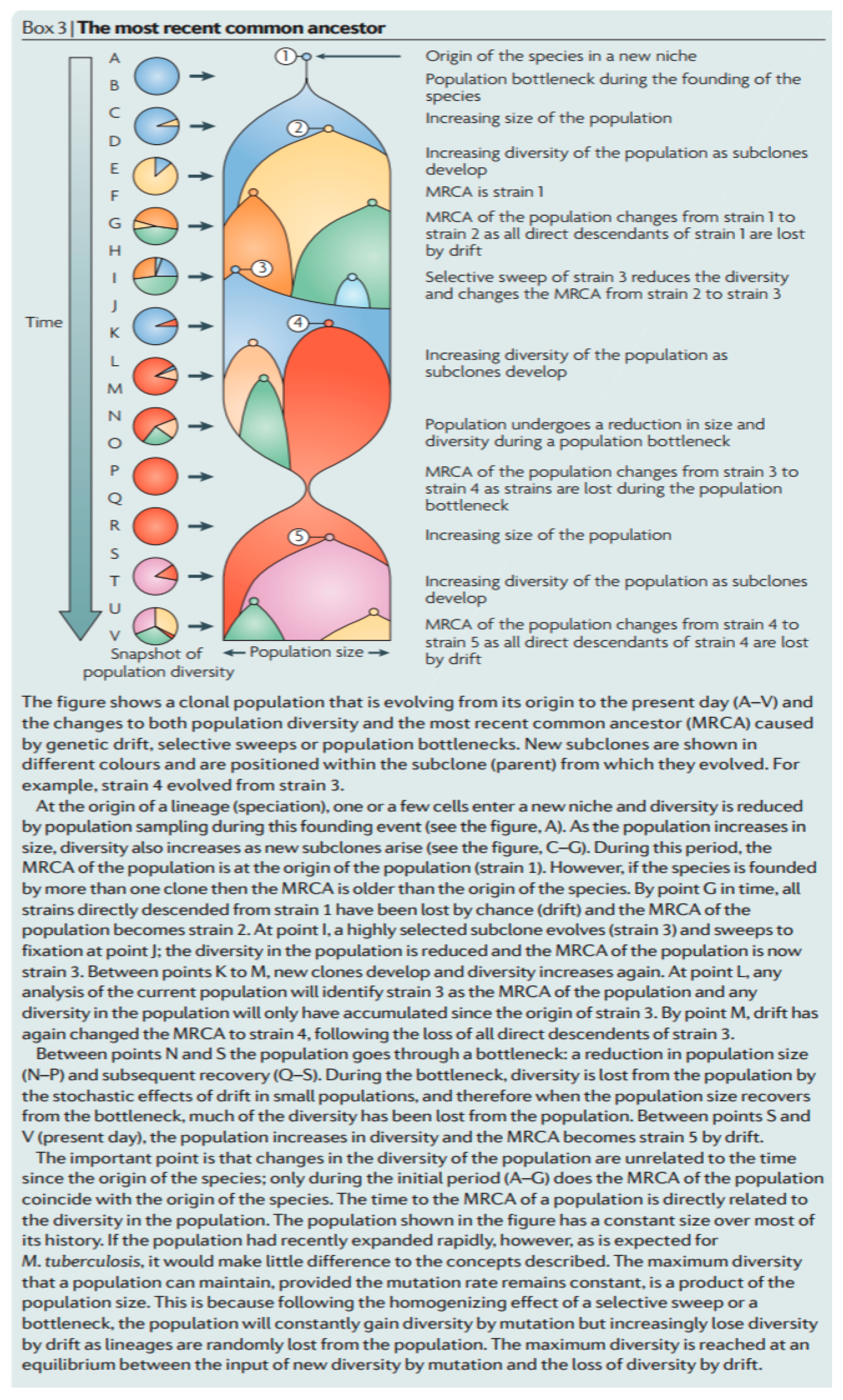

- “Every species has a most recent common ancestor (MRCA) that is the coalescence of all extant lineages. The MRCA of M. tuberculosis is not necessarily the first strain of M. tuberculosis to infect humans, and is no more than the coalescence of all extant lineages; it may have been one member of a large population of M. tuberculosis strains (Figure 10)”.

- (2)

- “The MRCA of M. tuberculosis, or any species, can change over time as lineages die out and the population evolves (Figure 10). The MRCA of a population is based on the sum of all extant strains, and if lineages become extinct then the MRCA will change. Both selective sweeps (the replacement of all alleles in a population by a selected allele) and drift (the random loss of lineages from a population by sampling each generation) can cause lineages to become extinct. For example, if Beijing strains of M. tuberculosis outcompete all other extant lineages then the MRCA of all extant M. tuberculosis strains will become a Beijing strain. This change in the MRCA of a species is common to all organisms, but is probably more important for clonal organisms such as M. tuberculosis, for which selective sweeps can drive whole chromosomes to fixation and purge all variation in the population.”

- (3)

- “M. tuberculosis may have infected humans for hundreds of thousands of years, or longer, before the current MRCA appeared, but those ancient lineages have been lost from the present population. Thus, molecular dating does not tell us how long humans and M. tuberculosis have coexisted (Figure 10)”.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Leprosy Strategy 2016–2020; Cooreman, E.A., Ed.; Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: www.who.int/lep/resources/9789290225096/en/ (accessed on 31 July 2017).

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2016. Available online: www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed on 31 July 2017).

- Gagneux, S. Host-pathogen co-evolution in human tuberculosis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2012, 367, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigelman, M.; Lemma, E. The use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in ancient skeletons. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 1993, 3, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, W.L.; Aufderheide, A.C.; Buikstra, J.; Holcomb, T.A. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in a pre-Columbian Peruvian mummy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 2091–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafi, A.; Spigelman, M.; Stanford, J.; Lemma, E.; Donoghue, H.; Zias, J. DNA of Mycobacterium leprae detected by PCR in ancient bone. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 1994, 4, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller-Christensen, V.; Hughes, D.R. Two early cases of leprosy in Great Britain. Man 1962, 62, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortner, D.J.; Putschar, W.J.G. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Spigelman, M.; Zias, J.; Gernaey-Child, A.M.; Minnikin, D.E. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA in calcified pleura from remains 1400 years old. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 27, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gernaey, A.M.; Minnikin, D.E.; Copley, M.S.; Dixon, R.A.; Middleton, J.C.; Roberts, C.A. Mycolic acids and ancient DNA confirm an osteological diagnosis of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2001, 81, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

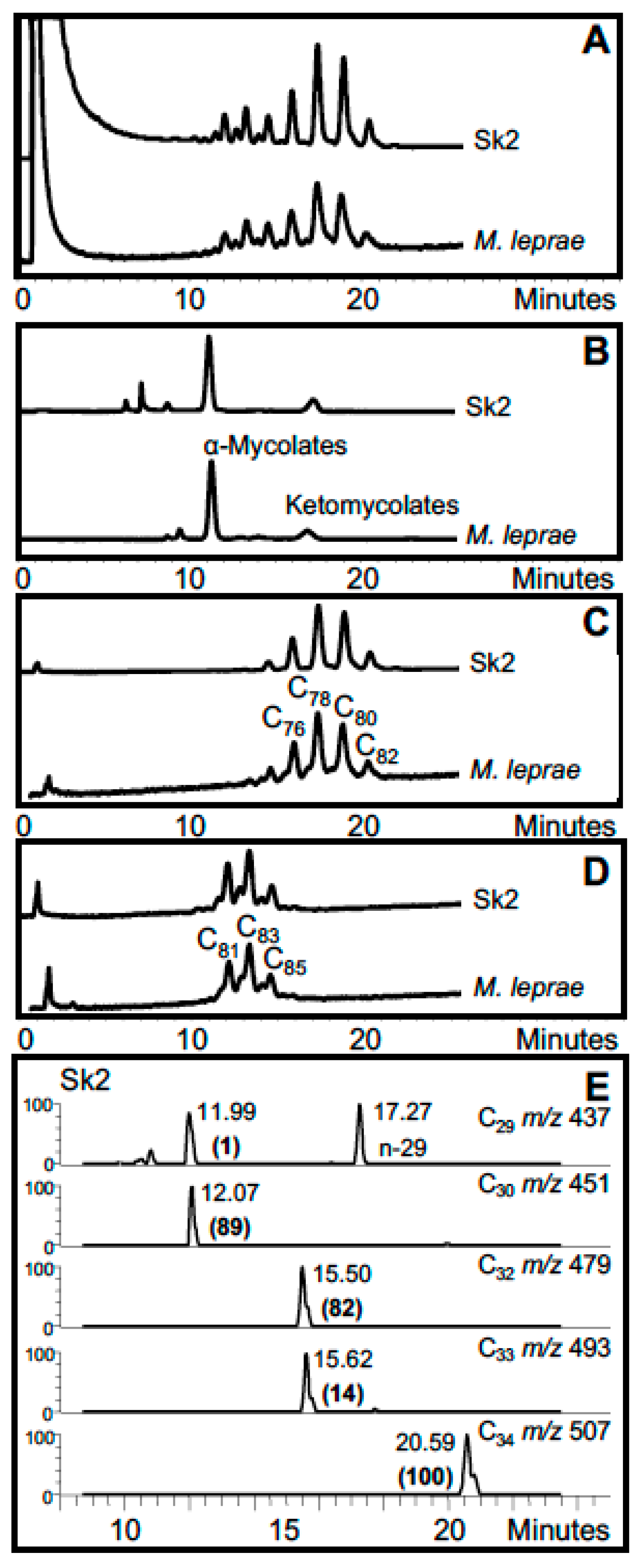

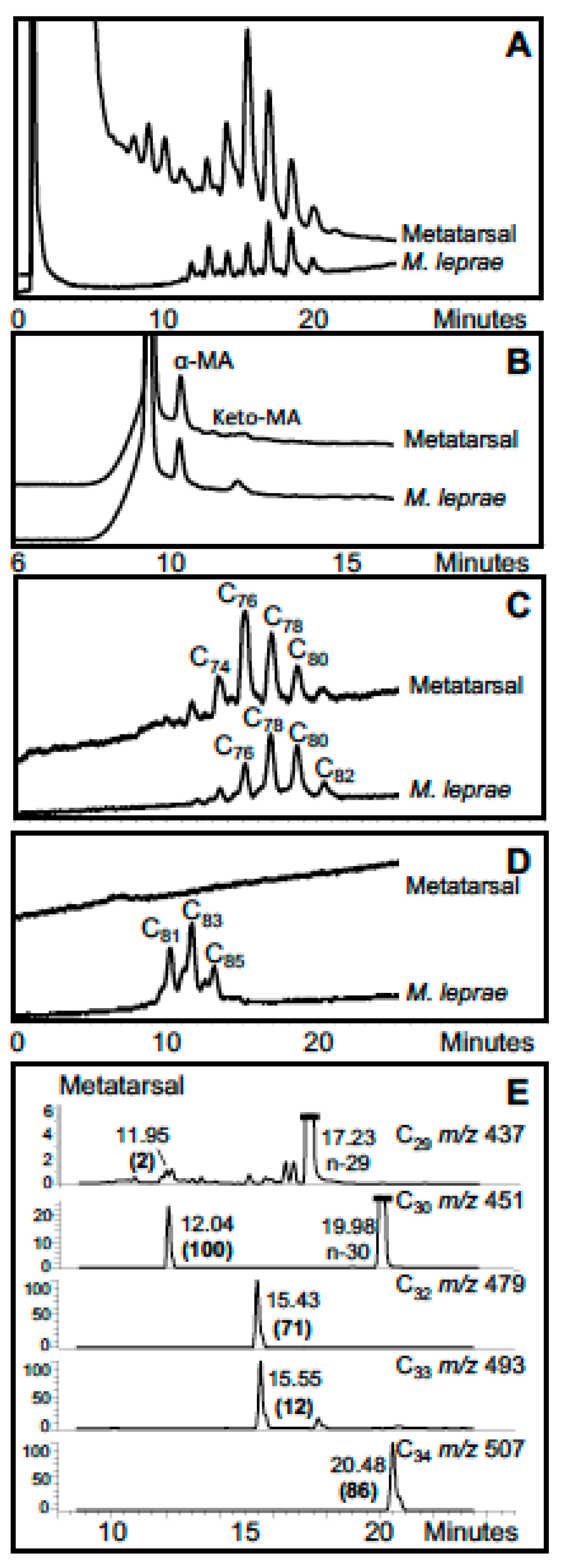

- Taylor, G.M.; Blau, S.; Mays, S.; Monot, M.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S.; Cole, S.T.; Rutland, P. Mycobacterium leprae genotype amplified from an archaeological case of lepromatous leprosy in central Asia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 2408–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Spigelman, M.; Donoghue, H.D. The interplay of DNA and lipid biomarkers in the detection of tuberculosis and leprosy in mummies and other skeletal remains. In Yearbook of Mummy Studies; Gill-Frerking, H., Rosendahl, W., Zink, A., Piombino-Mascali, D., Eds.; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: Munich, Germany, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, O.Y.-C.; Bull, I.D.; Molnár, E.; Marcsik, A.; Pálfi, G.; Donoghue, H.D.; Besra, G.S.; Minnikin, D.E. Integrated strategies for the use of lipid biomarkers in the diagnosis of ancient mycobacterial disease. In the Twelfth Annual Conference of the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge 2010; Mitchell, P.D., Buckberry, J., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Taylor, G.M.; Marcsik, A.; Molnár, E.; Pálfi, G.; Pap, I.; Teschler-Nicola, M.; Pinhasi, R.; Erdal, Y.S.; Velemínsky, P.; et al. A migration-driven model for the historical spread of leprosy in medieval Eastern and Central Europe. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 31, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagneux, S.; DeRiemer, K.; Van, T.; Kato-Maeda, M.; de Jong, B.C.; Narayanan, S.; Nicol, M.; Niemann, S.; Kremer, K.; Gutierrez, M.C.; et al. Variable host-pathogen compatibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 108, 2869–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, M.C.J. Putting leprosy on the map. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1264–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monot, M.; Honoré, N.; Garnier, T.; Araoz, R.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Lacroix, C.; Sow, S.; Spencer, J.S.; Truman, R.W.; Williams, D.L.; et al. On the origin of leprosy. Science 2005, 308, 1040–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monot, M.; Honoré, N.; Garnier, T.; Zidane, N.; Sherafi, D.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A.; Matsuoka, M.; Taylor, G.M.; Donoghue, H.D.; Bouwman, A.; et al. Comparative genomic and phylogeographic analysis of Mycobacterium leprae. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreevatsan, S.; Pan, X.; Stockbauer, K.E.; Connell, N.D.; Krieswirth, B.N.; Whittam, T.S.; Musser, J.M. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 9869–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.M.; Donoghue, H.D. Multiple loci variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) of Mycobacterium leprae isolates amplified from European archaeological human remains with lepromatous leprosy. Microb. Infect. 2011, 13, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamerbeek, J.; Schouls, L.; Kolk, A.; van Agterveld, M.; van Soolingen, D.; Kuijper, S.; Bunschoten, A.; Molhuizen, H.; Shaw, R.; Goyal, M.; et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arrieza, B.T.; Salo, W.; Aufderheide, A.C.; Holcomb, T.A. Pre-Columbian tuberculosis in northern Chile: Molecular and skeletal evidence. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1995, 98, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, H.; Hummel, S.; Herrmann, B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA in ancient human bones. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1996, 23, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, A.; Haas, C.J.; Reischl, U.; Szeimies, U.; Nerlich, A.G. Molecular analysis of skeletal tuberculosis in an ancient Egyptian population. J. Med. Microbiol. 2001, 50, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, H.A.; Donoghue, H.D.; Holton, J.; Pap, I.; Spigelman, M. Widespread occurrence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA from 18th–19th century Hungarians. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2003, 120, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathurst, R.R.; Barta, J.L. Molecular evidence of tuberculosis induced hypertrophic osteopathy in a 16th century Iroquoian dog. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2004, 31, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.M.; Murphy, E.; Hopkins, R.; Rutland, P.; Chistov, Y. First report of Mycobacterium bovis DNA in human remains from the Iron Age. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershkovitz, I.; Donoghue, H.D.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Gernaey, A.M.; Galili, E.; Eshed, V.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Lemma, E.; et al. Detection and molecular characterization of 9000-year-old Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithic settlement in the eastern Mediterranean. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

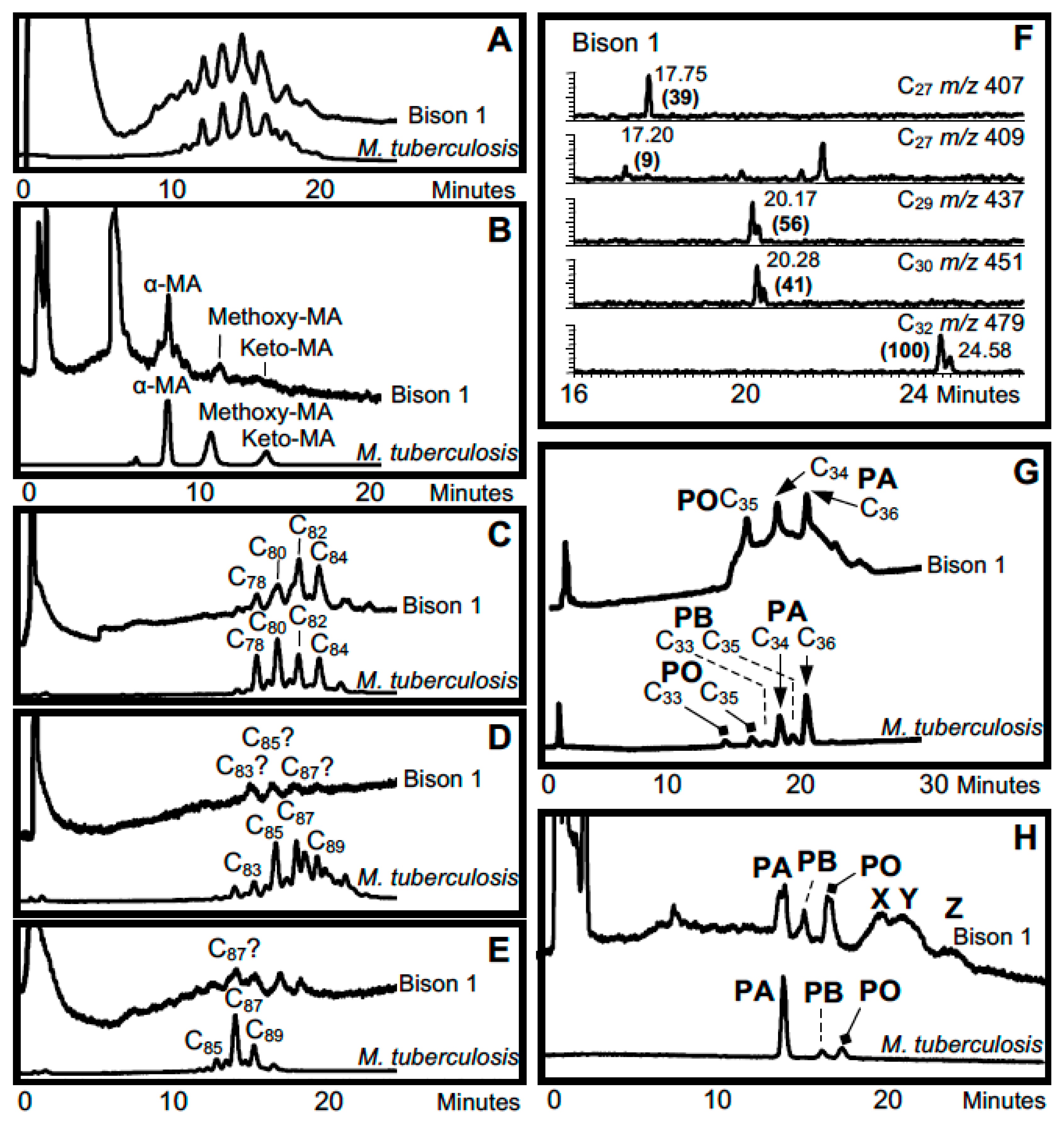

- Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Donoghue, H.D.; Spigelman, M.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Bull, I.D.; Rothschild, B.M.; Martin, L.D.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex lipid virulence factors preserved in the 17,000-year-old skeleton of an extinct bison, Bison antiquus. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwman, A.S.; Kennedy, S.L.; Müller, R.; Stephens, R.H.; Holst, M.; Caffell, A.C.; Roberts, C.A.; Brown, T.A. Genotype of a historic strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18511–18516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.Z.-M.; Sergeant, M.J.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S.; Pap, I.; Spigelman, M.; Donoghue, H.D.; Pallen, M.J. Metagenomic analysis of tuberculosis in a mummy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, K.I.; Harkins, K.M.; Herbig, A.; Coscolla, M.; Weber, N.; Comas, I.; Forrest, S.A.; Bryant, J.M.; Harris, S.R.; Schuenemann, V.J.; et al. Pre-Columbian mycobacterium genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis. Nature 2014, 514, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, G.L.; Sergeant, M.J.; Zhou, Z.; Chan, J.Z.-M.; Millard, A.; Quick, J.; Szikossy, I.; Pap, I.; Spigelman, M.; Loman, N.J.; et al. Eighteenth-century genomes show that mixed infections were common at time of peak tuberculosis in Europe. Nat. Comms. 2015, 6, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.M.; Widdison, S.; Brown, I.N.; Young, D. A mediaeval case of lepromatous leprosy from 13th–14th century Orkney, Scotland. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2000, 27, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Holton, J.; Spigelman, M. PCR primers that can detect low levels of Mycobacterium leprae DNA. J. Med. Microbiol. 2001, 50, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Marcsik, A.; Matheson, C.; Vernon, K.; Nuorala, E.; Molto, J.E.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Spigelman, M. Co-infection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae in human archaeological samples: A possible explanation for the historical decline of leprosy. Proc. R. Soc. B 2005, 272, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.M.; Watson, C.L.; Bouwman, A.S.; Lockwood, D.N.; Mays, S.A. Variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) typing of two palaeopathological cases of lepromatous leprosy from mediaeval England. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.M.; Tucker, K.; Butler, R.; Pike, A.W.G.; Lewis, J.; Roffey, S.; Marter, P.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Minnikin, D.E.; et al. Detection and strain typing of ancient Mycobacterium leprae from a medieval leprosy hospital. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuenemann, V.J.; Singh, P.; Mendum, T.A.; Krause-Kyora, B.; Jäger, G.; Bos, K.I.; Herbig, A.; Economou, C.; Benjak, A.; Busso, P.; et al. Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae. Science 2013, 341, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inskip, S.A.; Taylor, G.M.; Zakrzewski, S.R.; Mays, S.A.; Pike, A.W.G.; Llewellyn, G.; Williams, C.M.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Minnikin, D.E.; et al. Osteological, biomolecular and geochemical examination of an early Anglo-Saxon case of lepromatous leprosy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.M.; Crossey, M.; Saldanha, J.; Waldron, T. DNA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identified in mediaeval human skeletal remains using polymerase chain reaction. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1996, 23, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, A.G.; Haas, C.J.; Zink, A.; Szeimies, U.; Hagedorn, H.G. Molecular evidence for tuberculosis in an ancient Egyptian mummy. Lancet 1997, 350, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Collins Cook, D.; Pfeiffer, S. DNA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex identified in North America, pre-Columbian human skeletal remains. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1998, 25, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.M.; Goyal, M.; Legge, A.J.; Shaw, R.J.; Young, D. Genotypic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from medieval human remains. Microbiology 1999, 145, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, B.M.; Martin, L.D.; Lev, G.; Bercovier, H.; Kahila Bar-Dal, G.; Greenblatt, C.; Donoghue, H.; Spigelman, M.; Brittain, D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA from an extinct bison dated 17,000 years before the present. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mays, S.; Taylor, G.M. Osteological and biomolecular study of two possible cases of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy from mediaeval England. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2002, 29, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigelman, M.; Matheson, C.; Lev, G.; Greenblatt, C.; Donoghue, H.D. Confirmation of the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-specific DNA in three archaeological specimens. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2002, 12, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.M.; Stewart, G.R.; Cooke, M.; Chaplin, S.; Ladva, S.; Kirkup, J.; Palmer, S.; Young, D.B. Koch’s bacillus—A look at the first isolate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a modern perspective. Microbiology 2003, 149, 3213–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, A.R.; Sola, C.; Reischi, U.; Grabner, W.; Rastogi, N.; Wolf, H.; Nerlich, A.G. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNAs from Egyptian mummies by spoligotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.M.; Young, D.B.; Mays, S.A. Genotypic analysis of the earliest known prehistoric case of tuberculosis in Britain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 45, 2236–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigelman, M.; Pap, I.; Donoghue, H.D. A death from Langerhans cell histiocytosis and tuberculosis in 18th century Hungary—What palaeopathology can tell us today. Leukemia 2006, 20, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, C.D.; Vernon, K.K.; Lahti, A.; Fratpietro, R.; Spigelman, M.; Gibson, S.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Donoghue, H.D. Molecular exploration of the first-century Tomb of the Shroud in Akeldama, Jerusalem. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.M.; Chistov, Y.K.; Hopkins, R.; Rutland, P.; Taylor, G.M. Tuberculosis among Iron Age individuals from Tyva, South Siberia: Palaeopathological and biomolecular findings. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 2029–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, J.E.; Shaw, M.J.; Mallet, A.I.; Santos, A.L.; Roberts, C.A.; Gernaey, A.M.; Minnikin, D.E. Mycocerosic acid biomarkers for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in the Coimbra skeletal collection. Tuberculosis 2009, 89, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S.; Taylor, J.H.; Spigelman, M. Tuberculosis in Dr Granville’s mummy: A molecular re-examination of the earliest known Egyptian mummy to be scientifically examined and given a medical diagnosis. Proc. R. Soc. B 2010, 277, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Pap, I.; Szikossy, I.; Spigelman, M. Detection and characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in 18th century Hungarians with pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. In Yearbook of Mummy Studies; Gill-Frerking, H., Rosendahl, W., Zink, A., Piombino-Mascali, D., Eds.; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: Munich, Germany, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nicklisch, N.; Maixner, F.; Gansimeier, R.; Friederich, S.; Dresely, V.; Meller, H.; Zink, A.; Alt, K.W. Rib lesions in skeletons from early Neolithic sites in central Germany: on the trail of tuberculosis at the onset of agriculture. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 149, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corthals, A.; Koller, A.; Martin, D.W.; Rieger, R.; Chen, E.I.; Bernaski, M.; Recagno, G.; Dávalos, L.M. Detecting the immune system response of a 500 year-old Inca mummy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, M.; Molnár, E.; Donoghue, H.D.; Besra, G.S.; Minnikin, D.E.; Wu, H.H.T.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Bull, I.; Pálfi, G. Osteological and biomolecular evidence of a 7000-year-old case of hypertrophic pulmonary osteopathy secondary to tuberculosis from Neolithic Hungary. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lairemruata, A.; Ball, M.; Bianucci, R.; Weite, B.; Nerlich, A.G.; Kun, J.F.J.; Putsch, C.M. Molecular identification of falciparum malaria and human tuberculosis co-infections in mummies from the Fayum Depression (Lower Egypt). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60307. [Google Scholar]

- Dabernat, H.; Thèves, C.; Bouakaze, C.; Nikolaeva, D.; Keyser, C.; Mokrousov, I.; Géraut, A.; Duchesne, S.; Gérard, P.; Alexeev, A.N.; et al. Tuberculosis epidemiology and selection in an autochthonous Siberian population from the 16th–19th century. PLoS ONE 2013, 9, e89877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, R.; Roberts, C.A.; Brown, T.A. Biomolecular identification of ancient Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA in human remains from Britain and continental Europe. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2014, 153, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroska-Strugińska, B.; Druszczyńska, M.; Lorkiewicz, W.; Szewczyk, R.; Żądzińska, E. Mycolic acids as markers of osseus tuberculosis in the Neolithic skeleton from Kujawy region (central Poland). Anthropol. Rev. 2014, 77, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, O.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Minnikin, D.E.; Llewellyn, G.; Williams, C.M.; Maixner, F.; O’Sullivan, N.; Zink, A.; et al. Human tuberculosis predates domestication in ancient Syria. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, S4–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershkovitz, I.; Donoghue, H.D.; Minnikin, D.E.; May, H.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Feldman, M.; Galili, E.; Spigelman, M.; Rothschild, B.M.; Kahila Bar-Gal, G. Tuberculosis origin: The Neolithic scenario. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, S122–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Rothschild, B.M.; Spigelman, M.; Hershkovitz, I.; Kahila Bar-Gal, G.; Donoghue, H.D.; Minnikin, D.E. Lipid biomarkers provide evolutionary signposts for the oldest known cases of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, S127–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, M.; Bereczki, Z.; Molnár, E.; Donoghue, H.D.; Minnikin, D.E.; Lee, Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Bull, I.D.; Pálfi, G. 7000 year-old tuberculosis cases from Hungary—Osteological and biomolecular evidence. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, S13–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, C.J.; Zink, A.; Pálfi, G.; Szeimies, U.; Nerlich, A.G. Detection of leprosy in ancient human skeletal remains by molecular identification of Mycobacterium leprae. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 114, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigelman, M.; Donoghue, H.D. Brief communication: Unusual pathological condition in the lower extremities of a skeleton from ancient Israel. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2001, 114, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, R.; García, C.; Cañadas, M.P.; Isidro, A.; Guijo, J.M.; Malgosa, A. DNA sequences of Mycobacterium leprae recovered from ancient bones. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 226, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.L.; Popescu, E.; Boldsen, J.; Slaus, M.; Lockwood, D.N. Single nucleotide polymorphism analysis of European archaeological M. leprae DNA. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7547, (read formal correction). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Takigawa, W.; Tanigawa, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ishido, Y.; Kawashima, A.; Wu, H.; Akama, T.; Sue, M.; Yoshihara, A.; et al. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA from archaeological skeletal remains in Japan using whole genome amplification and polymerase chain reaction. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, C.; Kjellström, A.; Lidén, K.; Panagopoulos, I. Ancient-DNA reveals an Asian type of Mycobacterium leprae in medieval Scandinavia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 465–470, Corrigendum, p. 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendum, T.A.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Roffey, S.; Taylor, G.M.; Wu, H.; Singh, P.; Tucker, K.; Hinds, J.; Cole, S.T.; Kierzek, A.M.; et al. Mycobacterium leprae genomes from a British medieval leprosy hospital: Towards understanding an ancient epidemic. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnár, E.; Donoghue, H.D.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Minnikin, D.E.; Bull, I.D.; Llewellyn, G.; Williams, C.M.; Spekker, O.; et al. Morphological and biomolecular evidence for tuberculosis in 8th century AD skeletons from Bélmegyer-Csömöki domb, Hungary. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, S35–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Roffey, S.; Tucker, K.; Filipek-Ogden, K.; Montgomery, J.; Cameron, J.; O’Connell, T.; Evans, J.; Marter, J.; Taylor, G.M. Investigation of a medieval pilgrim burial excavated from the leprosarium of St Mary Magdalen Winchester, UK. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigelman, M.; Donoghue, H.D. Palaeobacteriology with special reference to pathogenic bacteria. In Emerging Pathogens: The Archaeology, Ecology, and Evolution of Infectious Disease; Greenblatt, C.L., Spigelman, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar, H.N.; Hofreiter, M.; Spauding, W.G.; Martin, P.S.; Stankiewicz, B.A.; Bland, H.; Evershed, R.P.; Possnert, G.; Pääbo, S. Molecular coproscopy: Dung and diet of the extinct ground sloth Nothrotheriops. shastensis. Science 1998, 281, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boom, R.; Sol, C.J.; Salimans, M.M.; Jansen, C.L.; Wertheim-van Dillen, P.M.; van der Noordaa, J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bouwman, A.S.; Brown, T.A. Comparison between silica-based methods for the extraction of DNA from human bones from 18th to mid-19th century London. Ancient Biomol. 2002, 4, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Al-Soud, W.; Rådström, P. Effects of amplification facilitators on diagnostic PCR in the presence of blood, feces, and meat. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 4463–4470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cano, R.J. Analysing ancient DNA. Endeavour 1996, 20, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telenti, A.; Imboden, P.; Marchesi, F.; Lowrie, D.; Cole, S.; Colston, M.J.; Matter, L.; Schopfer, K.; Bodmer, T. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, S.; Taylor, G.M.; Legge, A.J.; Young, D.B.; Turner-Walker, G. Am. J. Paleopathological and biomolecular study of tuberculosis in a medieval skeletal collection from England. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2001, 114, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostowy, S.; Inwald, J.; Gordon, S.; Martin, C.; Warren, R.; Kremer, K.; Cousins, D.; Behr, M.A. Revisiting the evolution of Mycobacterium bovis. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 6386–6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.K.; Taylor, G.M.; Jain, S.; Suneetha, L.M.; Suneetha, S.; Lockwood, D.N.J.; Young, D.B. Microsatellite mapping of Mycobacterium leprae populations in infected humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 4931–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Budiaswan, T.; Matsuoka, M. Diversity of potential short tandem repeats in Mycobacterium leprae and application for molecular typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5221–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supply, P.; Allix, C.; Lesjean, S.; Cardoso-Oelemann, M.; Rüsch-Gerdes, S.; Willery, E.; Savine, E.; de Haas, P.; van Deutekon, H.; Roring, S.; et al. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 4498–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.H.; Dale, J.; Inwald, J.; Palmer, S.I.; Gordon, S.V.; Hewinson, R.G.; Maynard Smith, J. The population structure of Mycobacterium bovis in Great Britain: Clonal expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15271–15275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, S.T. Encoded errors: Mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 52, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.M. Ancient DNA and the fingerprints of disease: Retrieving human pathogen genomic sequences from archaeological remains using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. In Molecular Diagnostics; Current Research and Applications; Huggett, J., O’Grady, J., Eds.; Caister Academic Press: Haverhill, Suffolk, UK, 2014; pp. 115–137. ISBN 978-1-908230-41-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gernaey, A.M.; Minnikin, D.E.; Copley, M.S.; Power, J.J.; Ahmed, A.M.S.; Dixon, R.A.; Roberts, C.A.; Robertson, D.J.; Nolan, J.; Chamberlain, A. Detecting ancient tuberculosis. Internet Archaeol. 1998, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnikin, D.E.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Nataraj, V.; Donoghue, H.D.; Ridell, M.; Watanabe, M.; Alderwick, L.; Bhatt, A.; Besra, G.S. Pathophysiological implications of cell envelope structure in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and related taxa. In Tuberculosis—Expanding Knowledge; Ribon, W., Ed.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2015; pp. 145–175. ISBN 978-953-51-2139-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild, B.M.; Martin, L.D. Did ice-age bovids spread tuberculosis? Naturwissenschaften 2006, 11, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, B.M.; Laub, R. Hyperdisease in the late Pleistocene: validation of an early 20th century hypothesis. Naturwissenschaften 2006, 11, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

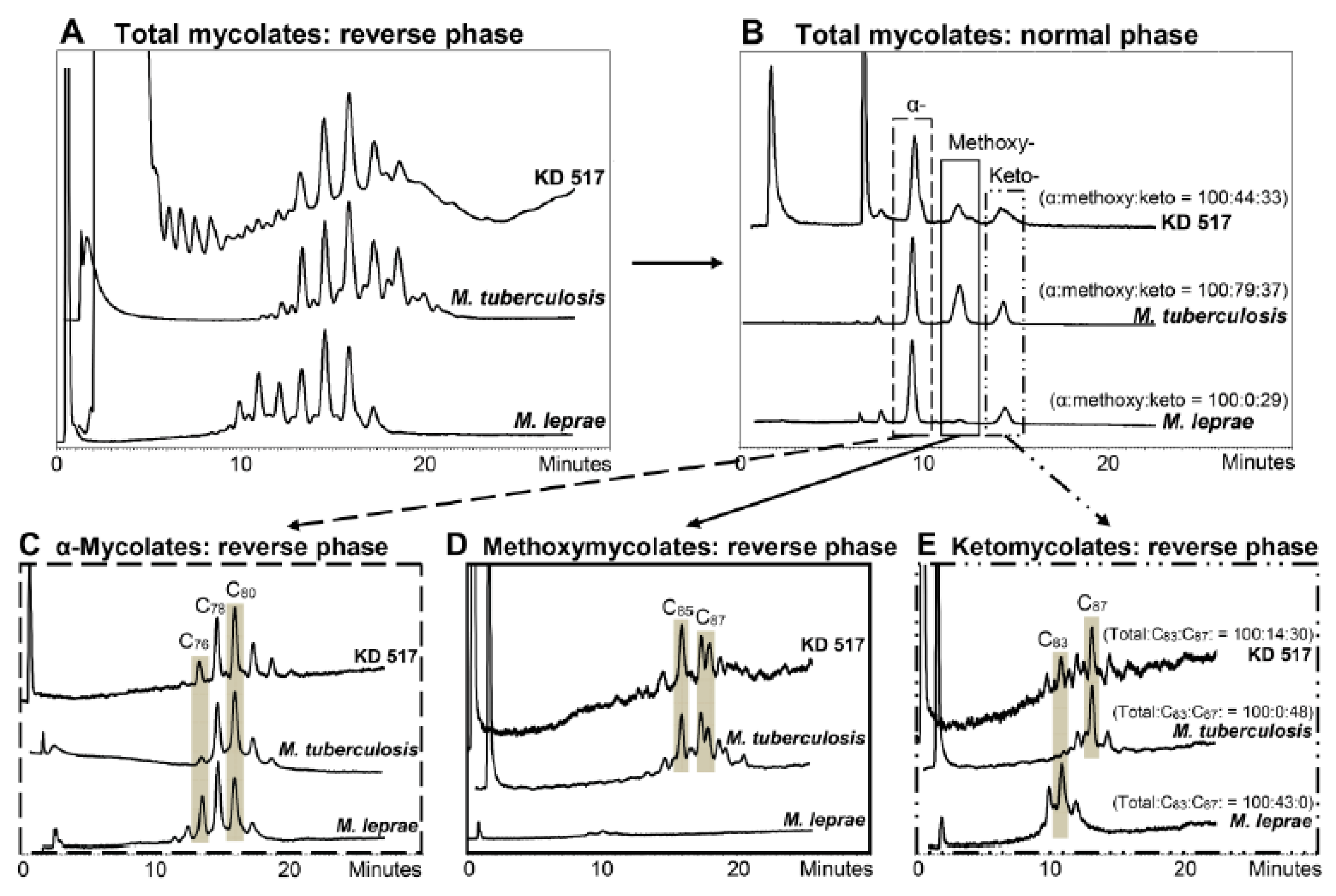

- Minnikin, D.E.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Bhatt, A.; Nataraj, V.; Rothschild, B.M.; Spigelman, M.; Donoghue, H.D. Ancient mycobacterial lipids: Key reference biomarkers in charting the evolution of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, S133–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankute, M.; Nataraj, V.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Ridell, M.; Garton, N.J.; Barer, M.R.; Minnikin, D.E.; Bhatt, A.; Besra, G.S. The role of hydrophobicity in tuberculosis evolution and pathogenicity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller-Christensen, V.; Weiss, D.L. One of the oldest datable skeletons with leprous bone-changes from the Naestved leprosy hospital churchyard in Denmark. Int. J. Lepr. 1971, 39, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, K.L.; Henneberg, R.J.; de Barros Lopes, M.; Henneberg, M. Evolution of human tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of paleopathological evidence. HOMO J. Comp. Hum. Biol. 2011, 62, 402–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.C.; Wilbur, A.K.; Buikstra, J.E.; Roberts, C.A. Tuberculosis and leprosy in perspective. Yearbk. Phys. Anthropol. 2009, 52, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilbur, A.K.; Bouwman, A.S.; Stone, A.C.; Roberts, C.A.; Pfister, L.-A.; Buikstra, J.E.; Brown, T.A. Deficiencies and challenges in the study of ancient tuberculosis DNA. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 1990–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Hershkovitz, I.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Galili, E.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Lemma, E.; Spigelman, M.; Kahila Bar-Gal, G. Biomolecular archaeology of ancient tuberculosis: Response to “Deficiencies and challenges in the study of ancient tuberculosis DNA” by Wilbur et al. (2009). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 2797–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.M.; Mays, S.A.; Huggett, J.F. Ancient DNA (aDNA) studies of man and microbes: General similarities, specific differences. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2010, 20, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkins, K.M.; Stone, A.C. Ancient pathogen genomics: insights into timing and adaptation. J. Hum. Evol. 2015, 79, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.-N.-N.; Aboudharam, G.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Beyond ancient microbial DNA: Nonnucleotidic biomolecules for paleomicrobiology. BioTechniques 2011, 50, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnikin, D.E.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Donoghue, H.D. Molecular markers for ancient tuberculosis. In Understanding tuberculosis—Deciphering the secret life of the bacilli; Cardona, P.-J., Ed.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 3–36. ISBN 978-953-307-946-2. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.H.; Hewinson, R.G.; Kremer, K.; Brosch, R.; Gordon, S.V. Myths and misconceptions: The origin and evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, D.; Gagneux, S. Co-evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Homo sapiens. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 264, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achtman, M. How old are bacterial pathogens? Proc. R. Soc. B 2016, 283, 20160990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, G.; Tripathy, V.M.; Misra, V.N.; Mohanty, R.K.; Shinde, V.S.; Gray, K.M.; Schug, M.D. Ancient skeletal evidence for leprosy in India (2000 B.C.). PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

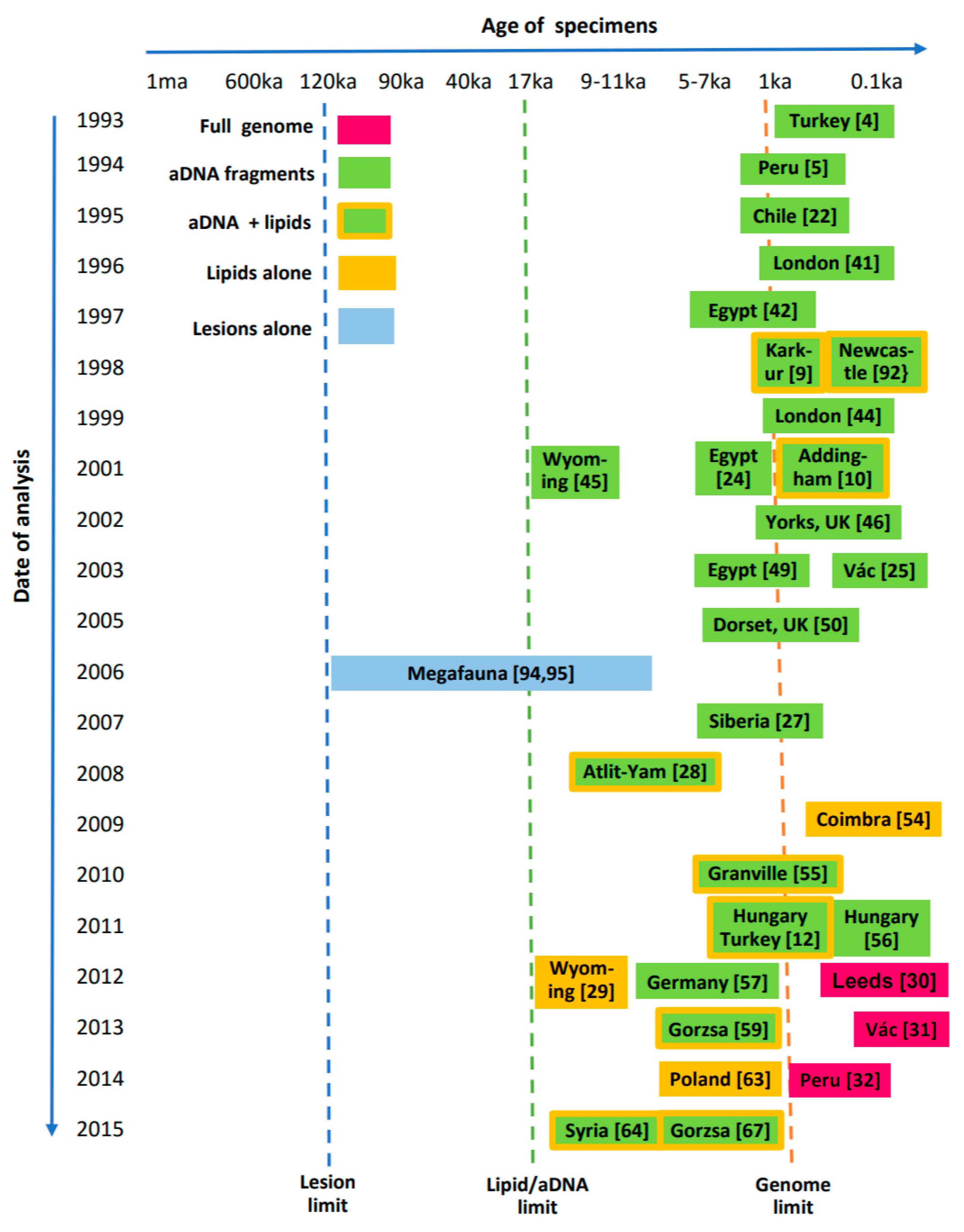

| Year | Techniques Introduced | Significance and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1993–1994 | aDNA fragment amplification: IS6110 123 bp and nested PCR | Proof of concept Positive results from skeletal & tissue samples [4,5] |

| 1995–1996 | aDNA fragment amplification: IS6110 PCR Confirmed by Sal1 digestion | MTB aDNA found in Pre-Columbian America [22] MTB aDNA found in bones without lesions [23] |

| 1998–1999 | Hot-start PCR IS6110, mtp40, oxyR, spoligotyping, DNA sequencing Mycolic acid biomarkers | M. tuberculosis specifically identified [44] MTB cell wall mycolic acids used to confirm aDNA findings [9,10]—significant as these are detected directly with no amplification |

| 2001–2003 | Additional PCR markers used including IS1081, outer & internal primers for TbD1 deletion region and spoligotyping | M. africanum found in Middle Kingdom ancient Egypt [24] MTB genotyped in 18th cent. Hungarian natural mummies [25] |

| 2004 | PCR for canine aDNA and MTB IS6110 | A 16th century Iroquoian dog had human MTB [26] |

| 2007–2008 | PCR for IS6110, IS1081, TbD1, RD regions, oxyR285 and pncA169 Improved mycolic acid detection | First finding of Mycobacterium bovis in human skeletal remains [27] ‘Modern MTB’ in early Neolithic [28] |

| 2012 | Mycolipenic and mycocerosic acid lipid biomarkers | Specific mycolipenate and clear mycocerosate pattern confirms MTB in ~17 ka bison [29] |

| 2012–2016 | Hybridization capture with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Metagenomics of 18th cent. MTB Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Identification of 19th cent. MTB genome [30] Mixed MTB genomes in 18th cent. Hungarians [31,32,33] |

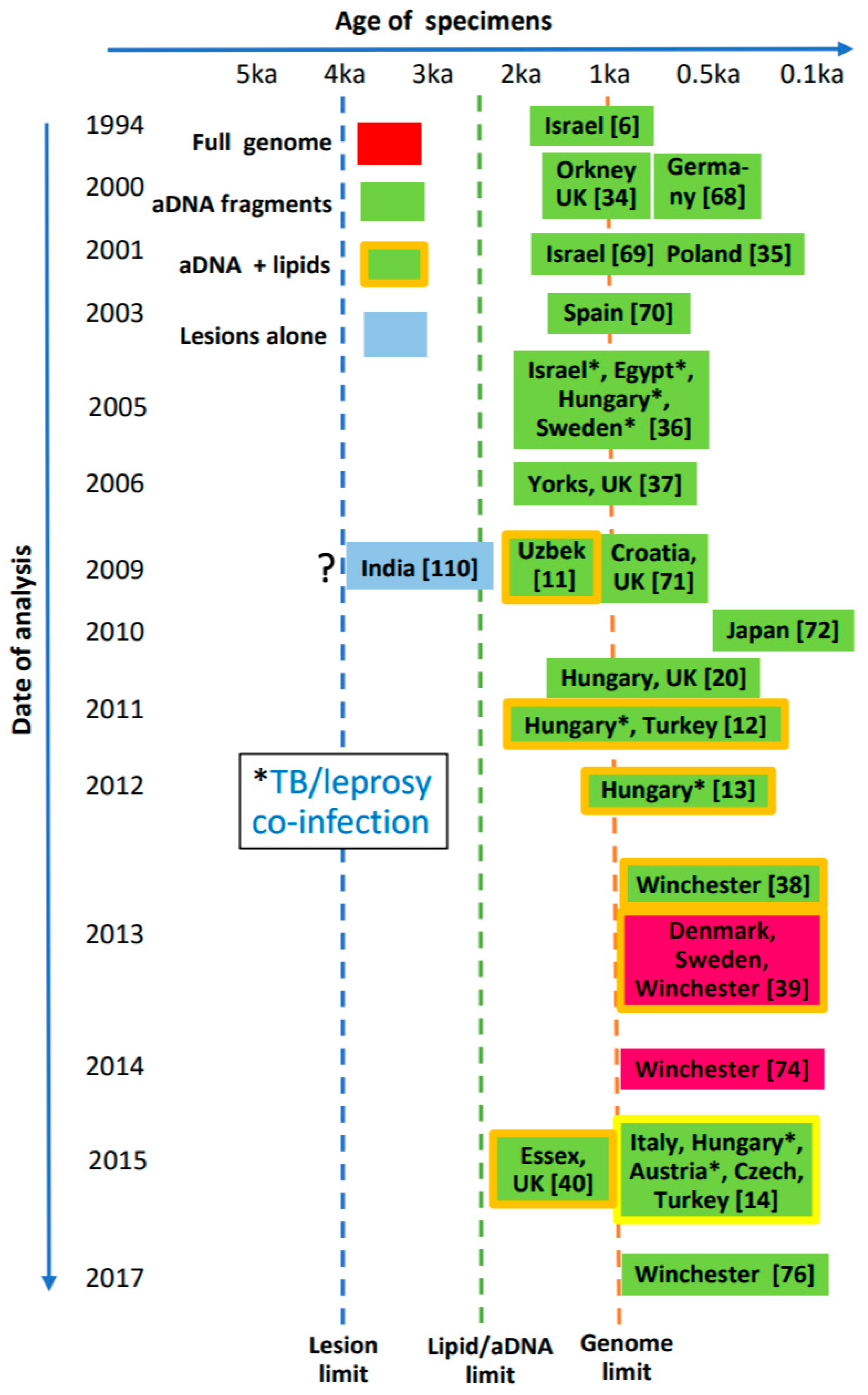

| Year | Techniques introduced | Significance and examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | aDNA fragment amplification, with PCR primers for large target regions (459 and 530 bp) | Proof of concept Positive results indicate excellent M. leprae aDNA preservation [6] |

| 2000–2001 | aDNA amplification based on specific RLEP region Nested & hemi-nested PCR used to target shorter sequences | M. leprae found in 11th–12th cent. Orkney, Scotland, UK [34] M. leprae identified in Medieval Poland, 10th and 15th century Hungary [35] |

| 2005 | Primers devised for nested PCR for both M. leprae aDNA and MTB IS6110 | Leprosy/TB co-infections identified in the absence of palaeopathology [36] |

| 2006 | Used hemi-nested & VNTR typing based on repetitive sequences | Different strains of M. leprae identified [37] |

| 2009 | Genotyping based on SNPs Mycolic acid lipid biomarkers | SNP typing reveals human origins of M. leprae and migrations [18] M. leprae mycolic acids detected [11] |

| 2012–2017 | SNP sub-genotyping and WGS Mycocerosic acid lipid biomarkers identified | SNP sub-genotyping elucidates geographical differences between M. leprae from different regions [14,38,39,40] |

| Burial | Region | Century CE | (AGA) 20 | (GTA) 9 | 21-3 | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sk2 | Winchester, UK | 10th–12th | 11 | 8 | 2 | 3I |

| Sk7 | “ | “ | 13 | 8 | 2 | 3I |

| Sk8 | “ | “ | 14 | 8 | 2 | 2F |

| Sk14 | “ | “ | 14 | 8 | 2 | 2F |

| Sk19 | “ | “ | 14 | 7 | Fail | 3I |

| Sk27 | “ | 11th | 12 | 7 | 2 | 2F |

| G708 | Yorkshire, UK | 10th–12th | 10 | 8 | 3 | 3 |

| GC96 | Essex, UK | 5th–6th | 14 | 6 | 2 | 3I |

| 1914 | Ipswich, UK | 13th–15th | 12 | 9 | 2 | 3I |

| Uzbek | Uzbekistan | 1st–4th | 22 | 9 | 2 | 3L |

| KD271 | Hungary | 7th | 16 | 24 | 2 | 3K |

| 503 | Hungary | 10th–11th | 18 | 8 | 2 | 3K |

| 222 | Hungary | 10th–11th | 12 | 12 | 2 | 3K |

| KK02 | Turkey | 8th–9th | 12 | 11 | 2 | 3K |

| 188 | Czech Republic | 9th | 11 | 7 | 2 | 3M |

| Criteria | Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | Run in-batch replicates | Run repeat assays | Run repeat extracts |

| Independent replication | Different operators (in-house) | Second centre replication | - |

| PCR specificity | Check Tm of melt curve and size on gel | Amplicon reported by specific probes | Amplicon sequencing |

| Cloning of amplicons | Cloning & sequencing to assess damage or miscoding changes | - | - |

| Appropriate molecular behaviour | Degraded templates Assess upper size limit | aDNA tends to high Cq values on real time platforms | Genotyping data should make phylogenetic sense |

| Controls | Extraction blanks to test reagents | PCR template blanks (water) | Burials lacking lesions & soil samples |

| Genotyping | SNP/deletion typing | VNTR analysis | NGS with controls to judge environmental contribution |

| Quantitative PCR | Assess aDNA at sites both with and without lesions | - | - |

| Independent biomarkers of disease | Mycobacterial lipid biomarkers | Recovery of peptides/proteins/ sugars | - |

| Analysis of associated remains | Animal remains for evidence of pathogen diseases | Animal remains for evidence of faunal DNA | - |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donoghue, H.D.; Taylor, G.M.; Stewart, G.R.; Lee, O.Y.-C.; Wu, H.H.T.; Besra, G.S.; Minnikin, D.E. Positive Diagnosis of Ancient Leprosy and Tuberculosis Using Ancient DNA and Lipid Biomarkers. Diversity 2017, 9, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d9040046

Donoghue HD, Taylor GM, Stewart GR, Lee OY-C, Wu HHT, Besra GS, Minnikin DE. Positive Diagnosis of Ancient Leprosy and Tuberculosis Using Ancient DNA and Lipid Biomarkers. Diversity. 2017; 9(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d9040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonoghue, Helen D., G. Michael Taylor, Graham R. Stewart, Oona Y. -C. Lee, Houdini H. T. Wu, Gurdyal S. Besra, and David E. Minnikin. 2017. "Positive Diagnosis of Ancient Leprosy and Tuberculosis Using Ancient DNA and Lipid Biomarkers" Diversity 9, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d9040046

APA StyleDonoghue, H. D., Taylor, G. M., Stewart, G. R., Lee, O. Y.-C., Wu, H. H. T., Besra, G. S., & Minnikin, D. E. (2017). Positive Diagnosis of Ancient Leprosy and Tuberculosis Using Ancient DNA and Lipid Biomarkers. Diversity, 9(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d9040046