Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Daytime Video Monitoring for Bird, Insect, and Other Wildlife Interactions with Photovoltaic Solar Energy Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

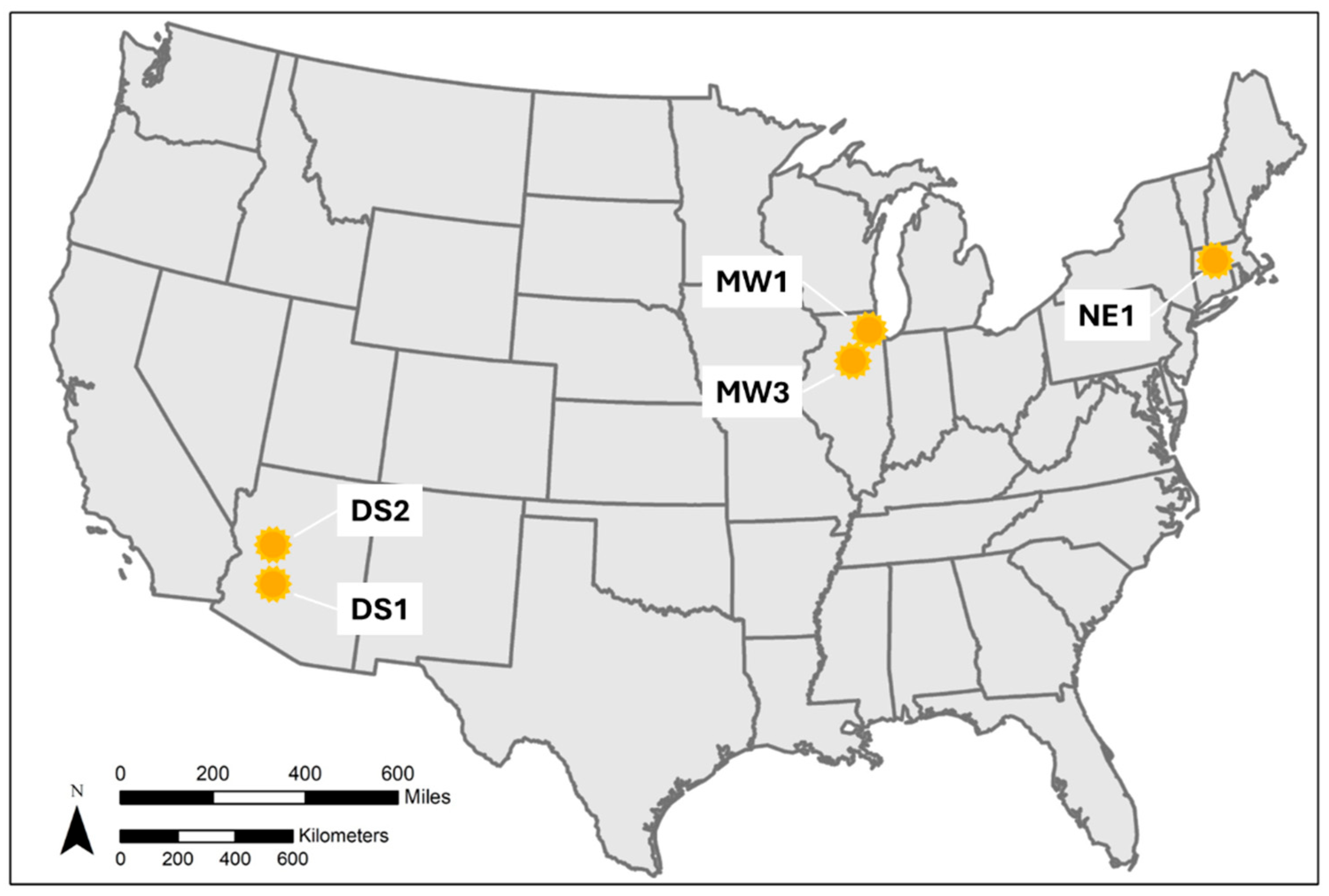

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Instrumentation and Data

2.3. Collecting Daytime Observations of Birds, Insects, and Other Wildlife

2.3.1. Extracting Moving Objects from Videos Using an AI Model

2.3.2. Extracting of Daytime Observations of Bird, Insect, and Other Wildlife from the MODT AI Model Output

2.4. Analyzing Daytime Observations of Birds, Insects, and Other Wildlife

3. Results

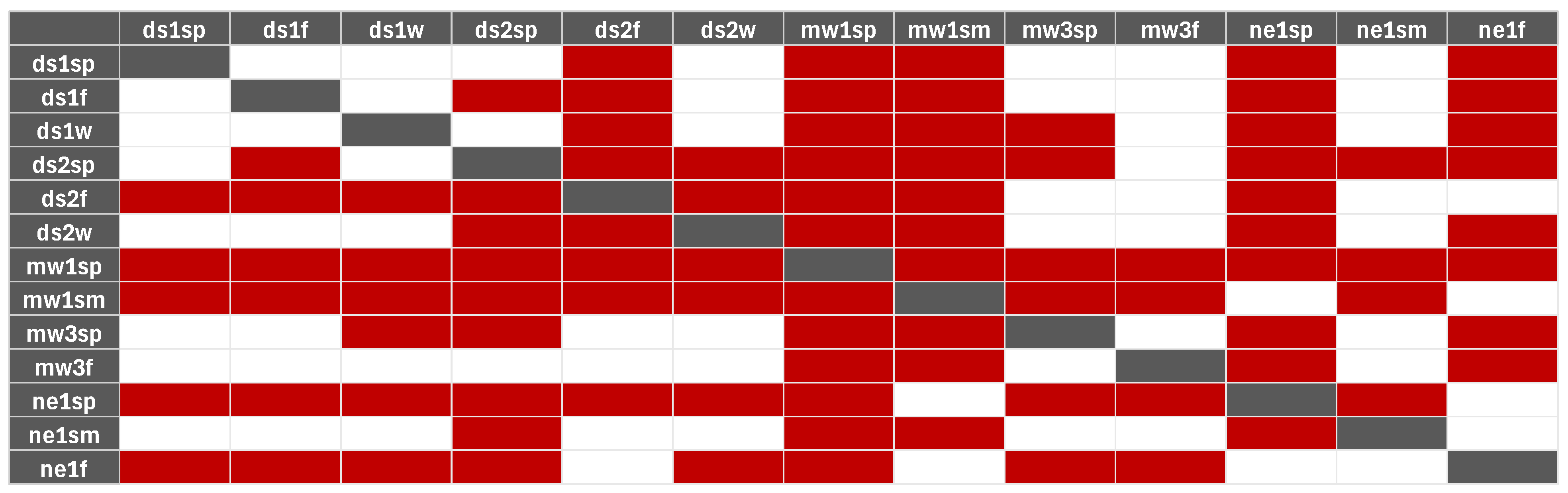

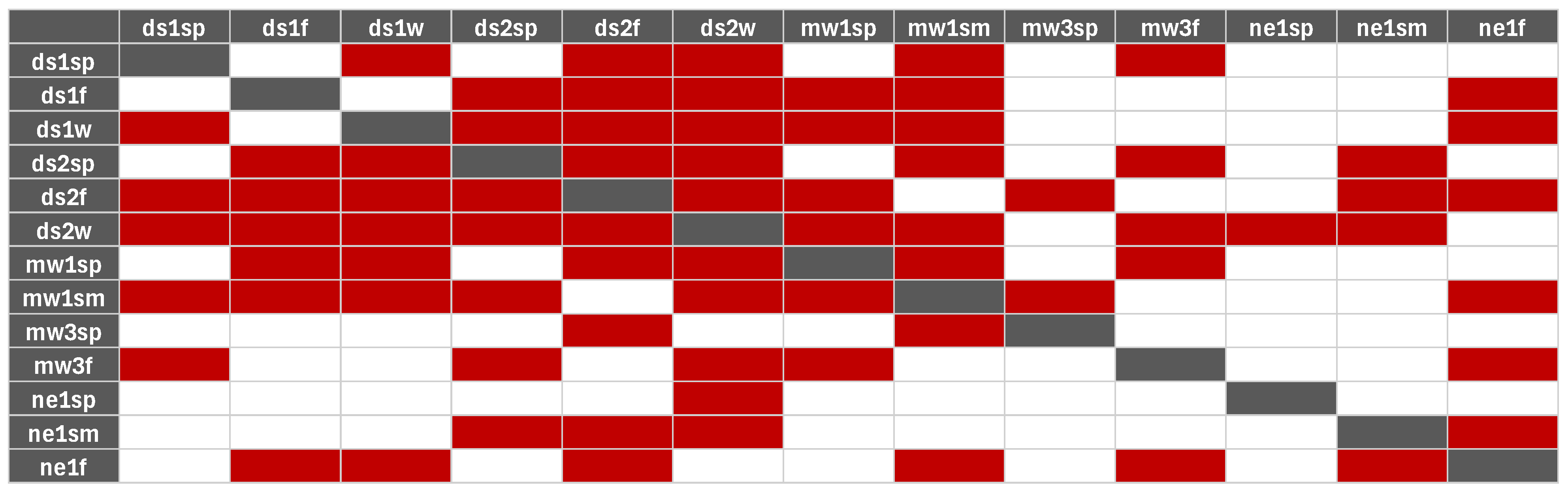

3.1. Daytime Birds Observations Collected from the Videos

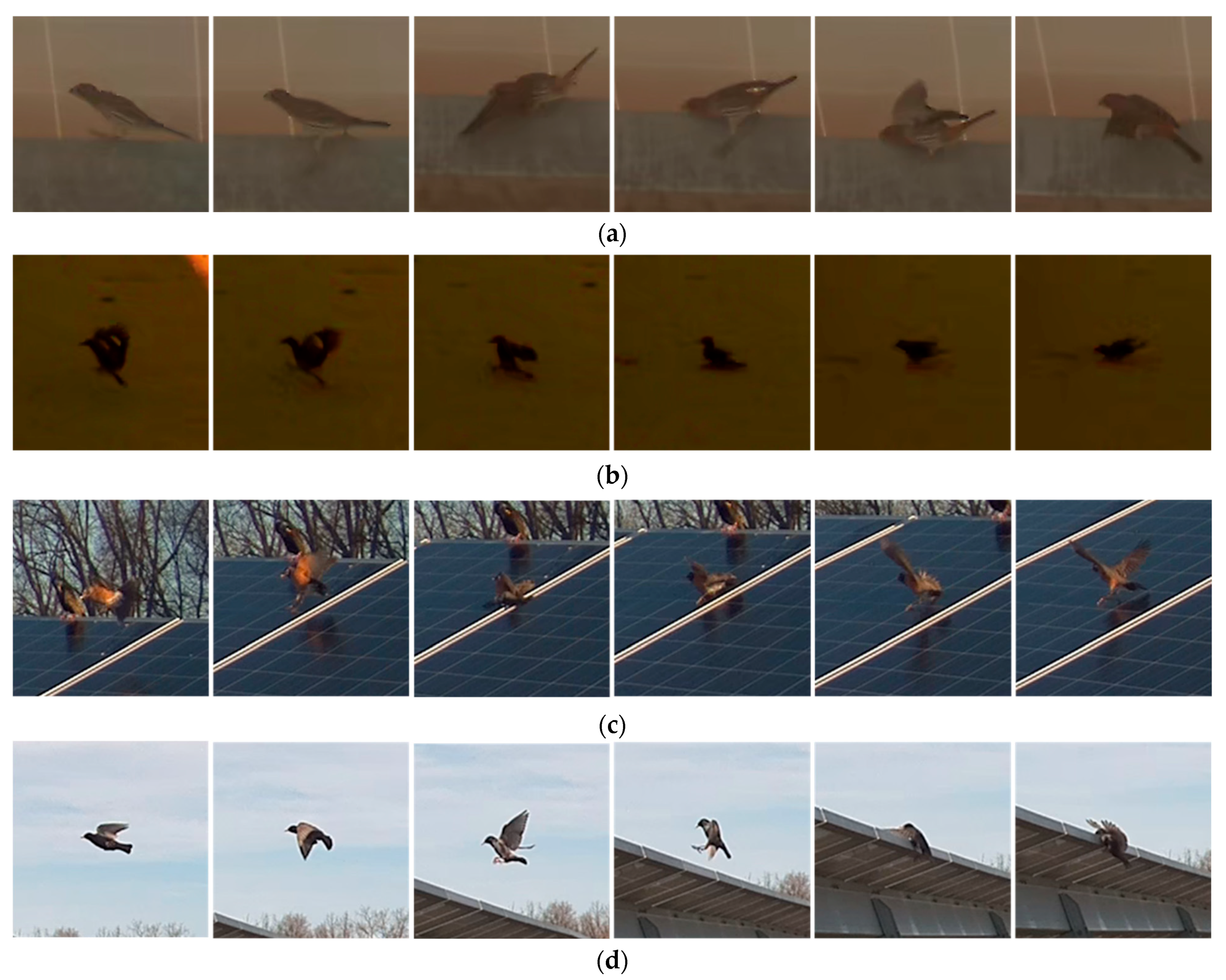

3.2. Daytime Bird Activities

3.3. Other Daytime Bird Behavioral Observations

3.4. Daytime Insects and Other Wildlife Observations

3.4.1. Insects

3.4.2. Other Wildlife

4. Discussion

4.1. MODT AI Model and Human Interpretation

4.2. Bird Occurrence and Activity

4.3. Bird Mortality, Lake Effect Hypothesis, and Limitations of Current Study

4.4. Insect and Other Wildlife Occurrences

4.5. Limitations and Disclaimers

4.6. Recommendations for Operational Use of AI-Assisted Daytime Video Monitoring for Birds and Insects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| Aug. | August |

| B | Bird |

| CA | California |

| Dec. | December |

| df | Degree of freedom |

| DS1 | Desert Southwest 1 site |

| DS2 | Desert Southwest 2 site |

| FL | Florida |

| ft | Feet |

| h | Hour |

| H | Human interpretation |

| in | Inch |

| Jun. | June |

| km | Kilometer |

| lb | Pound |

| Mar. | March |

| MODT | Moving object detection and tracking |

| MW1 | Midwest 1 site |

| MW3 | Midwest 3 site |

| MWac | Megawatt of alternating current |

| NB | Not bird |

| NE1 | Northeast 1 site |

| NJ | New Jersey |

| PoE | Power over ethernet |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| Qt | Quart |

| s | Second |

| Sep. | September |

| TB | Terabyte |

| USA | United States of America |

| VA | Virginia |

Appendix A

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| Video camera | Sighthound Compute Camera 4 (Sighthound. Inc., Longwood, FL, USA; https://www.sighthound.com/products/hardware) |

| Platform | Tripod (Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 118 1/8 In, Mfr. Model # 40-6330); Tripod adapter (Johnson Level & Tool 40-6863, 5/8″-11 to 1/4″-20 Thread); Sandbag (50 lb); and Cinder block |

| Data storage unit | Seagate 4TB portable hard drive (one drive per week, Fremont, CA, USA); Single board computer (Raspberry pi [varying models]), GeekPi Raspberry Pi 4 Armor Case with Fan; TRENDnet Gigabit PoE injector (Torrance, CA, USA); Ethernet cables (Cat6 Ethernet Cable, 10 ft with a dust cap and 3 ft); Extension cords (indoor-rated 3 ft, outdoor-rated 100 ft); Enclosure (56 Qt trunk); Exhaust cap (Dundas Jafine ProMax 4″); and Bungee cord (48 in) |

| Taxonomic Level | Desert Southwest 1 | Desert Southwest 2 | Midwest 1 | Midwest 3 | Northeast 1 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | 15.2% | 14.3% | 16.3% | 17.4% | 65.4% | 25.7% |

| Genus/family | 26.9% | 28.8% | 20.1% | 16.1% | 66.6% | 31.7% |

| Order | 59.2% | 66.9% | 50.3% | 61.9% | 82.3% | 64.1% |

| Broad category | 74.5% | 78.9% | 65.7% | 65.8% | 85.9% | 74.1% |

| Undetermined 1 | 25.5% | 21.1% | 34.3% | 34.2% | 14.1% | 25.9% |

| Site and Season | df | Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desert Southwest 1 | |||

| All seasons combined | 5 | 29,328.9 | <0.001 |

| fall | 5 | 21,047.7 | <0.001 |

| spring | 5 | 3581.2 | <0.001 |

| winter | 5 | 5355.4 | <0.001 |

| Desert Southwest 2 | |||

| All seasons combined | 5 | 4678.1 | <0.001 |

| fall | 5 | 4040.9 | <0.001 |

| spring | 5 | 252.6 | <0.001 |

| winter | 5 | 599.1 | <0.001 |

| Midwest 1 | |||

| All seasons combined | 5 | 14,880.5 | <0.001 |

| spring | 5 | 1031.6 | <0.001 |

| summer | 5 | 5398.7 | <0.001 |

| Midwest 3 | |||

| All seasons combined | 5 | 15,894.7 | <0.001 |

| fall | 5 | 5803.1 | <0.001 |

| summer | 5 | 10,873.6 | <0.001 |

| Northeast 1 | |||

| All seasons combined | 5 | 63,180.3 | <0.001 |

| fall | 5 | 20,171.8 | <0.001 |

| spring | 5 | 38,345.1 | <0.001 |

| summer | 5 | 6829.5 | <0.001 |

References

- International Energy Agency. Renewables 2024—Analysis and Forecast to 2030. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2024 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Nijsse, F.J.M.M.; Mercure, J.-F.; Ameli, N.; Larosa, F.; Kothari, S.; Rickman, J.; Vercoulen, P.; Pollitt, H. The momentum of the solar energy transition. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Solar Futures Study; Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/solar/solar-futures-study (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hernandez, R.R.; Easter, S.B.; Murphy-Mariscal, M.L.; Maestre, F.T.; Tavassoli, M.; Allen, E.B.; Barrows, C.W.; Belnap, J.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Ravi, S.; et al. Environmental impacts of utility-scale solar energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.V.; Dokter, A.M.; Blancher, P.J.; Sauer, J.R.; Smith, A.C.; Smith, P.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Panjabi, A.; Helft, L.; Parr, M.; et al. Decline of the north American avifauna. Science 2019, 366, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walston, L.J.; Hartmann, H.M.; Fox, L.; Stanger, M.E.; Steele, S.E.; Narváez, N.R.; Szoldatits, K.E.; Hogstrom, I.; Macknick, J. Ecovoltaic solar energy development can promote grassland bird communities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 62, 3341–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Catasús, J.; Morales, M.B.; Giralt, D.; González del Portillo, D.; Manzano-Rubio, R.; Solé-Bujalance, L.; Sardà-Palomera, F.; Traba, J.; Bota, G. Solar photovoltaic energy development and biodiversity conservation: Current knowledge and research gaps. Conserv. Lett. 2024, 17, e13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karban, C.C.; Lovich, J.E.; Grodsky, S.M.; Munson, S.M. Predicting the effects of solar energy development on plants and wildlife in the Desert Southwest, United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 205, 114823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, R.A.; Viner, T.C.; Trail, P.W.; Espinoza, E.O. Avian mortality at solar energy facilities in southern California: A preliminary analysis. Natl. Fish Wildl. Forensics Lab. 2014, 28, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciuch, K.; Riser-Espinoza, D.; Gerringer, M.; Erickson, W. A summary of bird mortality at photovoltaic utility scale solar facilities in the Southwestern US. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosciuch, K.; Riser-Espinoza, D.; Moqtaderi, C.; Erickson, W. Aquatic habitat bird occurrences at photovoltaic solar energy development in Southern California, USA. Diversity 2021, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walston, L.J.; Rollins, K.E.; LaGory, K.E.; Smith, K.P.; Meyers, S.A. A preliminary assessment of avian mortality at utility-scale solar energy facilities in the United States. Renew. Energy 2016, 92, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarčuška, B.; Gálffyová, M.; Schnürmacher, R.; Baláž, M.; Mišík, M.; Repel, M.; Fulín, M.; Kerestúr, D.; Lackovičová, Z.; Mojžiš, M.; et al. Solar parks can enhance bird diversity in agricultural landscape. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klehr, A.L.; Laskowski, A.N.; King, D.I. Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis) nesting in photovoltaic solar energy facilities in eastern New York. Northeast. Nat. 2024, 31, N30–N34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturchio, M.A.; Knapp, A.K. Ecovoltaic principles for a more sustainable, ecologically informed solar energy future. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, E7, 1746–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huso, M.M.; Dietsch, T.; Nicolai, C. Mortality Monitoring Design for Utility-Scale Solar Power Facilities; U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2016-1087; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2016; 44p. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Annual NLCD Collection 1 Science Products (ver. 1.1, June 2025). In U.S. Geological Survey Data Release; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.C.S.; Kamath, C. Robust background subtraction with foreground validation for urban traffic video. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2005, 2005, 726261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, Z. Improved adaptive Gaussian mixture model for background subtraction. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Cambridge, UK, 26 August 2004; Volume 2, pp. 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, Z.; Van Der Heijden, F. Efficient adaptive density estimation per image pixel for the task of background subtraction. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Golawski, A.; Mitrus, C.; Jankowiak, Ł. Increased bird diversity around small-scale solar energy plants in agricultural landscape. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conkling, T.J.; Vander Zanden, H.B.; Allison, T.D.; Diffendorfer, J.E.; Dietsch, T.V.; Duerr, A.E.; Fesnock, A.L.; Hernandez, R.R.; Loss, S.R.; Nelson, D.M.; et al. Vulnerability of avian populations to renewable energy production. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, R.; Robertson, B.; Kosciuch, K. Investigating the “Lake Effect” Influence on Avian Behavior from California’s Utility-Scale Photovoltaic Solar Facilities; California Energy Commission: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2021; Publication Number: CEC-500-2024-055.

- Evans, W.R.; Mellinger, D.K. Monitoring grassland birds in nocturnal migration. Stud. Avian Biol. 1999, 19, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

| Desert Southwest 1 | Desert Southwest 2 | Midwest 1 | Midwest 3 | Northeast 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site specification | |||||

| Area (hectares) | ~30 | ~40 | <1 | ~50 | ~3 |

| Capacity (MWac) | 10 | 15 | <1 | 20 | 3.5 |

| Year of operation (years) 1 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 8 |

| Axis type | Single axis | Single axis | Fixed tilt | Fixed tilt | Fixed tilt |

| Video collected (hours) 2 | 12,156 | 3113 | 219 | 3215 | 3809 |

| Video processed (hours) | 1939 | 325 | 159 | 558 | 1392 |

| Start of video collection | September 2020 | September 2020 | August 2019 | March 2021 | August 2023 |

| End of video collection | December 2023 | September 2022 | May 2020 | May 2023 | June 2024 |

| Land cover composition within a 5 km radius area 3 | |||||

| Open water | 0.6% | 0.0% | 3.5% | 0.1% | 0.8% |

| Developed, open space | 20.6% | 0.8% | 17.5% | 1.9% | 8.4% |

| Developed, low intensity | 18.2% | 1.8% | 25.9% | 5.3% | 5.2% |

| Developed, medium intensity | 19.7% | 0.3% | 19.3% | 0.4% | 1.8% |

| Developed, high intensity | 2.7% | 0.0% | 4.9% | 0.0% | 0.6% |

| Barren land | 0.0% | 15.2% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.4% |

| Deciduous forest | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.2% | 2.6% | 31.7% |

| Evergreen forest | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 3.0% |

| Mixed forest | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 0.1% | 14.4% |

| Shrub/scrub | 9.1% | 81.9% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Grasslands/herbaceous | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| Pasture/hay | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 2.9% | 17.1% |

| Cultivated crops | 29.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 86.1% | 3.2% |

| Woody wetlands | 0.1% | 0.0% | 9.5% | 0.3% | 12.2% |

| Emergent herbaceous wetlands | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.0% | 0.1% | 0.7% |

| Bird Activity Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fly over above | Flying above the solar panels high enough that no track images contain solar panel(s). |

| Fly through | Flying right above, between, and under solar panels. At least one track image contains a portion of solar panel. |

| Perch on panel | Flying in and landing on any part of the solar panels, including supporting infrastructure, or perching on a panel and flying away. |

| Land on ground | Flying in and landing on the ground or being on the ground and flying away. |

| Perch in background | Flying in and landing on any background object/infrastructure (e.g., powerline, building, and tree) or perching on the background object and flying away. |

| Collision * | Forcibly colliding with any part of the solar panels, including surface, edge, corner, and foundation, in a manner different from perching behavior. It is likely the bird will fall to the ground after the collision, but it is possible that a disoriented bird will fly away. |

| Season | Desert Southwest 1 | Desert Southwest 2 | Midwest 1 | Midwest 3 | Northeast 1 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video recording processed (hours) | Spring | 298 | 64 | 109 | 387 | 779 | 1637 |

| Summer | na | na | 50 | na | 302 | 352 | |

| Fall | 1199 | 138 | na | 171 | 311 | 1819 | |

| Winter | 442 | 123 | na | na | na | 565 | |

| Total | 1939 | 325 | 159 | 558 | 1392 | 4373 | |

| Bird observation collected | Spring | 1488 | 242 | 5467 | 5287 | 22,222 | 34,706 |

| Summer | na | na | 1950 | na | 5298 | 7248 | |

| Fall | 9487 | 2428 | na | 1927 | 10,874 | 24,716 | |

| Winter | 1667 | 309 | na | na | na | 1976 | |

| Total | 12,642 | 2979 | 7417 | 7214 | 38,394 | 68,646 | |

| Average rate of bird observation (per hour) [standard error] 2 | Spring | 6.6 [1.06] | 3.1 [0.52] | 65.3 [4.34] | 14.7 [2.92] | 42.0 [2.80] | na |

| Summer | na | na | 37.1 [2.27] | na | 11.9 [2.65] | na | |

| Fall | 6.9 [0.97] | 14.3 [1.32] | na | 6.5 [1.56] | 36.4 [6.83] | na | |

| Winter | 3.3 [0.43] | 6.1 [0.91] | na | na | na | na |

| Bird Behavior | Description |

|---|---|

| Mating | Displaying courtship, allopreening, and/or (attempted) copulation. |

| Nesting | Carrying nesting material, food, or a fecal sac. Entering/exiting nest sites. |

| Foraging | Searching and/or gathering food on the ground and in mid-air. |

| Self-maintenance | Preening and/or wiping bill. |

| Territorial/aggressive | Displaying defensive or aggressive postures (e.g., puffing feathers) or direct confrontations (e.g., chasing). |

| Season | Desert Southwest 1 | Desert Southwest 2 | Midwest 1 | Midwest 3 | Northeast 1 | Total or Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insect observation collected | Spring | 745 | 107 | 217 | 1691 | 2355 | 5115 |

| Summer | na | na | 889 | 0 | 1231 | 2120 | |

| Fall | 9600 | 1948 | na | 4737 | 564 | 16,849 | |

| Winter | 1857 | 27 | na | na | na | 1884 | |

| Total | 12,202 | 2082 | 1106 | 6428 | 4150 | 25,968 | |

| Average rate of insect observation (per hour) [standard error] 2 | Spring | 3.5 [0.72] | 2.5 [0.44] | 2.4 [0.35] | 4.5 [1.07] | 12.1 [2.83] | na |

| Summer | na | na | 17.5 [1.15] | na | 8.3 [1.58] | na | |

| Fall | 9.8 [1.69] | 25.7 [2.83] | na | 15.1 [2.82] | 1.5 [0.44] | na | |

| Winter | 7.7 [0.98] | 0.7 [0.14] | na | na | na | na |

| Season | Desert Southwest 1 | Desert Southwest 2 | Midwest 1 | Midwest 3 | Northeast 1 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other wildlife observation collected | Spring | 2 | 17 | 37 | 0 | 15 | 71 |

| Summer | na | na | 2 | na | 6 | 8 | |

| Fall | 62 | 13 | na | 0 | 11 | 86 | |

| Winter | 0 | 4 | na | na | na | 4 | |

| Total | 64 | 34 | 39 | 0 | 32 | 169 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hamada, Y.; Szymanski, A.Z.; Tarpey, P.F.; Walston, L.J. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Daytime Video Monitoring for Bird, Insect, and Other Wildlife Interactions with Photovoltaic Solar Energy Facilities. Diversity 2026, 18, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020095

Hamada Y, Szymanski AZ, Tarpey PF, Walston LJ. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Daytime Video Monitoring for Bird, Insect, and Other Wildlife Interactions with Photovoltaic Solar Energy Facilities. Diversity. 2026; 18(2):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020095

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamada, Yuki, Adam Z. Szymanski, Paul F. Tarpey, and Leroy J. Walston. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Daytime Video Monitoring for Bird, Insect, and Other Wildlife Interactions with Photovoltaic Solar Energy Facilities" Diversity 18, no. 2: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020095

APA StyleHamada, Y., Szymanski, A. Z., Tarpey, P. F., & Walston, L. J. (2026). Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Daytime Video Monitoring for Bird, Insect, and Other Wildlife Interactions with Photovoltaic Solar Energy Facilities. Diversity, 18(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020095