Rhopilema nomadica in the Mediterranean: Molecular Evidence for Migration and Insights into Its Proliferation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

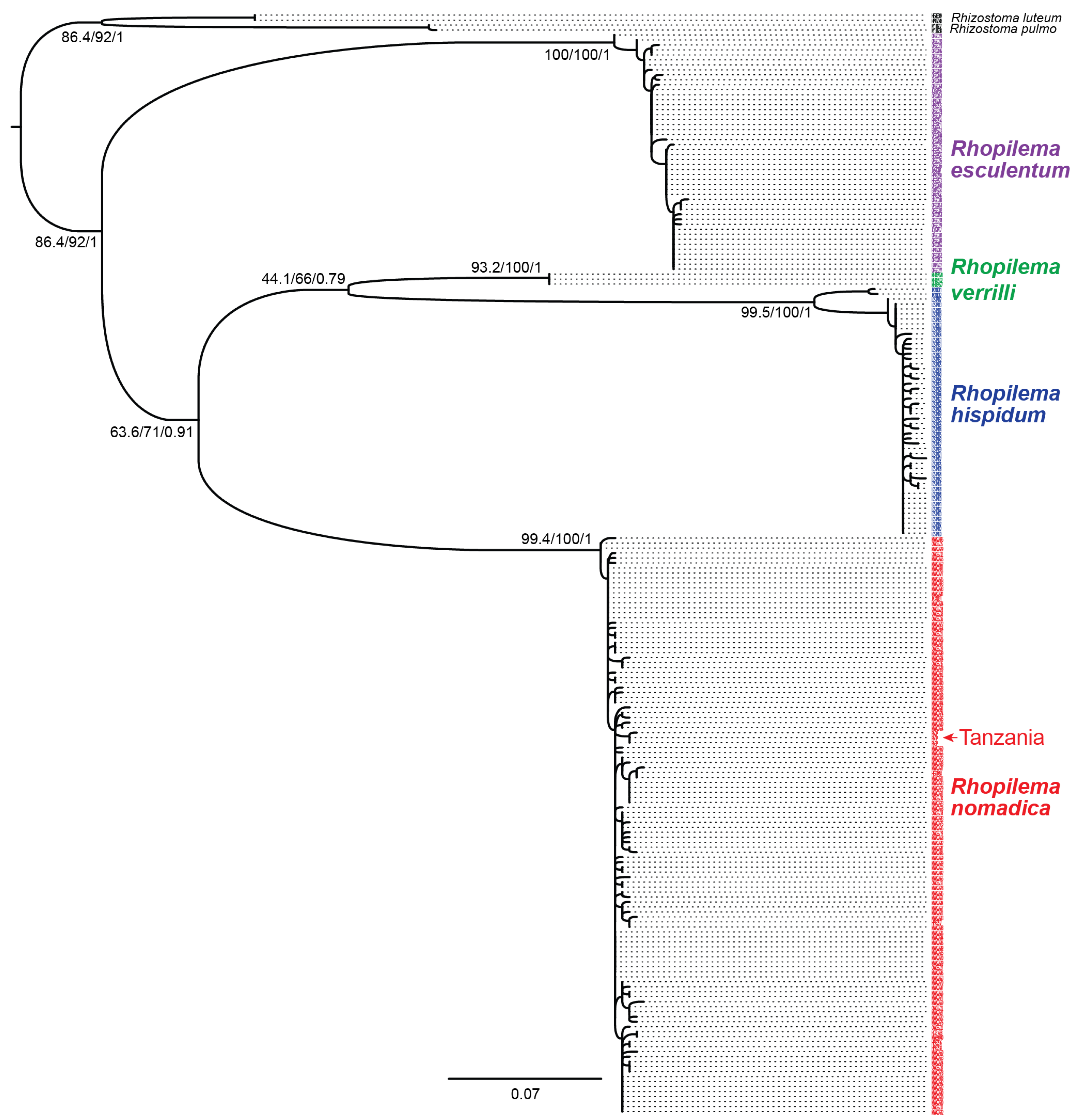

DNA Sampling, Amplification, and Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galil, B.; Spanier, E.; Ferguson, W. The Scyphomedusae of the Mediterranean Coast of Israel, Including Two Lessepsian Migrants New to the Mediterranean. Zool. Meded. 1990, 64, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier, E. Swarming of Jellyfishes along the Mediterranean Coast of Israel. Isr. J. Zool. 1989, 36, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

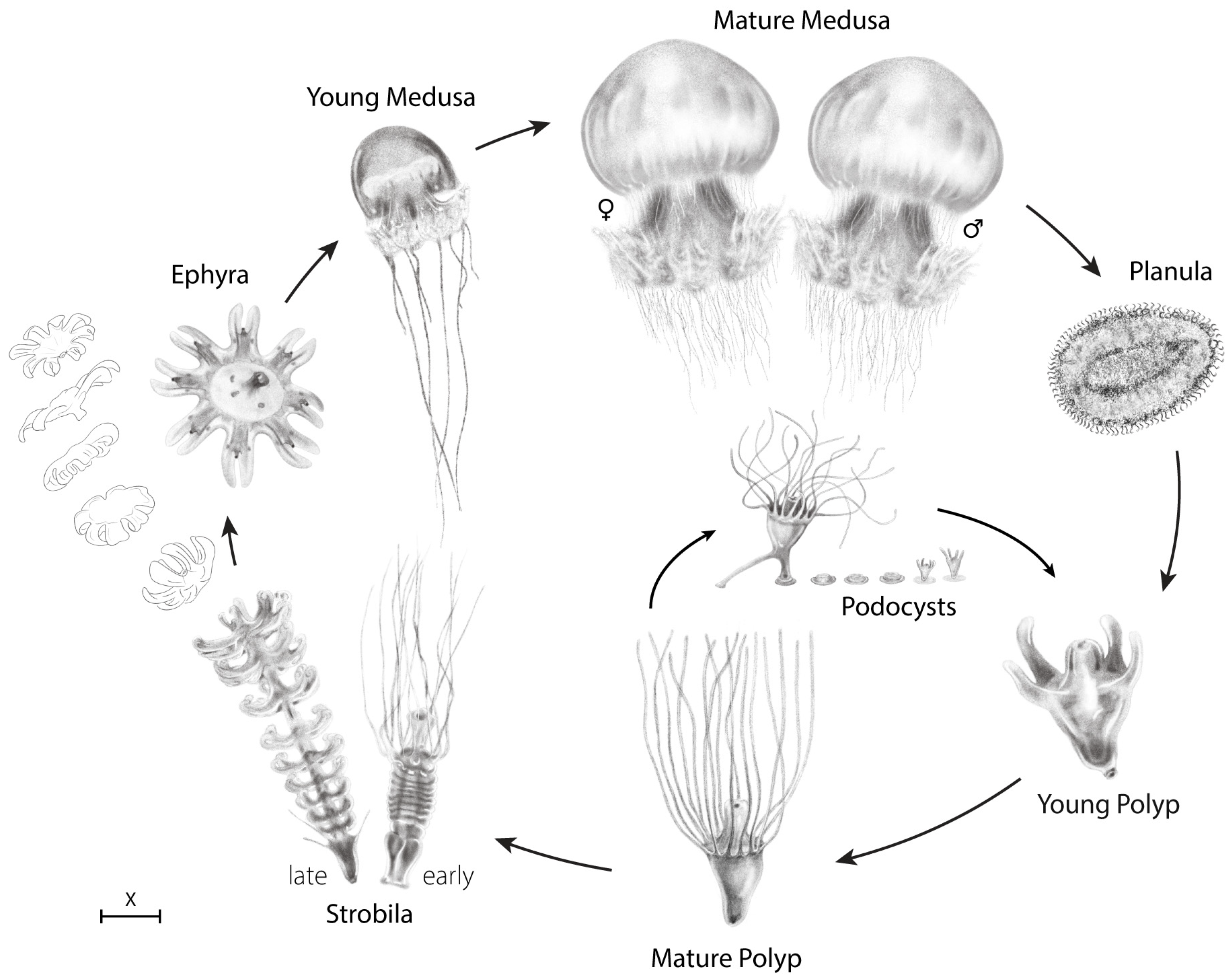

- Lotan, A.; Ben-Hillel, R.; Loya, Y. Life Cycle of Rhopilema nomadica: A New Immigrant Scyphomedusan in the Mediterranean. Mar. Biol. 1992, 112, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.S.; Zenetos, A. A Sea Change—Exotics in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. In Invasive Aquatic Species of Europe: Distribution, Impacts and Management; Leppäkoski, E., Gollasch, S., Olenin, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 325–336. [Google Scholar]

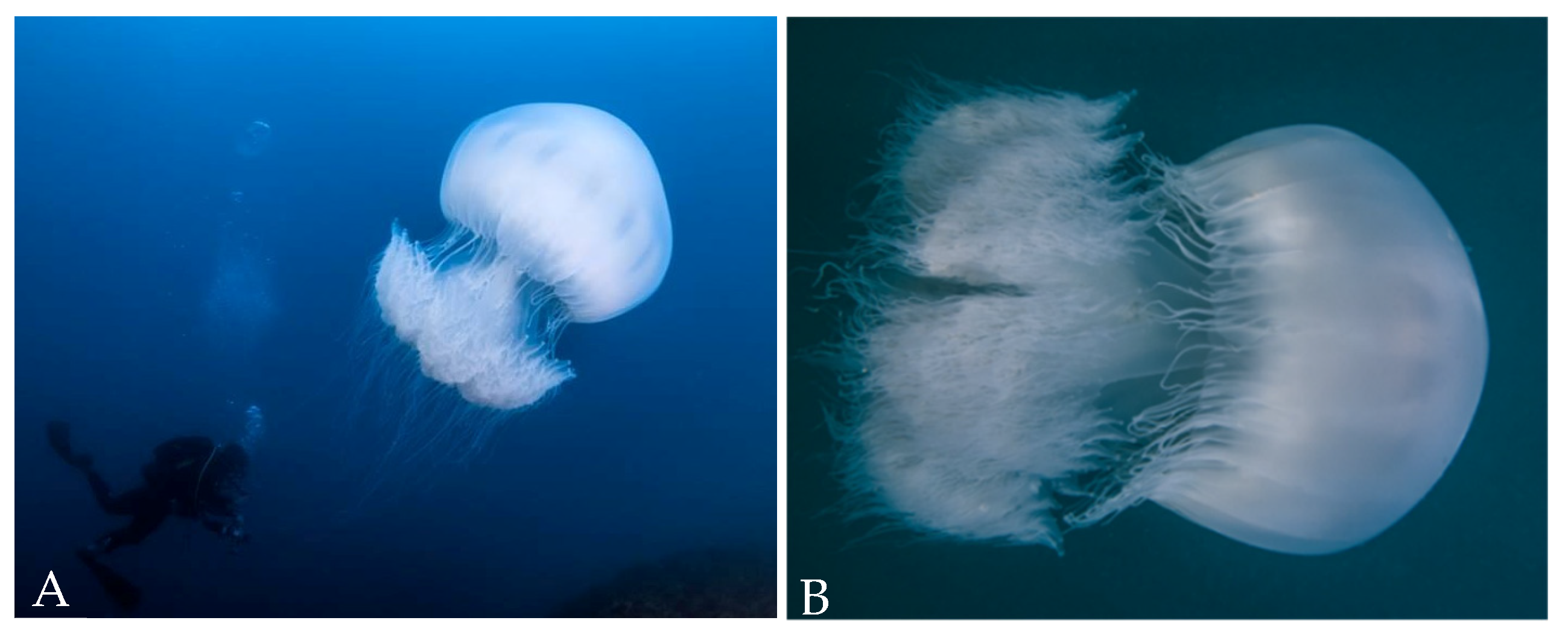

- Öztürk, B.; İşinibilir, M. An Alien Jellyfish Rhopilema nomadica and Its Impacts to the Eastern Mediterranean Part of Turkey. J. Black Sea/Mediterr. Environ. 2010, 16, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Siokou-Frangou, I. First Record of the Scyphomedusa Rhopilema nomadica Galil, 1990 (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) in Greece. Aquat. Invasions 2006, 1, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deidun, A.; Arrigo, S.; Piraino, S. The Westernmost Record of Rhopilema nomadica (Galil, 1990) in the Mediterranean—Off the Maltese Islands. Aquat. Invasions 2011, 6, S99–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Yahia, M.N.; Daly-Yahia, O.K.; Gueroun, S.K.M.; Aissi, M.; Deidun, A.; Fuentes, V.; Piraino, S. The Invasive Tropical Scyphozoan Rhopilema nomadica Galil, 1990 Reaches the Tunisian Coast of the Mediterranean Sea. BioInvasions Rec. 2013, 2, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, P.; Spiga, A.; Deidun, A.; Gueroun, S.K.M.; Daly-Yahia, M.N. Further Spread of the Venomous Jellyfish Rhopilema nomadica Galil, Spannier & Ferguson, 1990 (Rhizostomeae, Rhizostomatidae) in the Western Mediterranean. BioInvasions Rec. 2017, 6, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streftaris, N.; Zenetos, A. Alien Marine Species in the Mediterranean—The 100 ‘Worst Invasives’ and Their Impact. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2006, 7, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilov, G.; Galil, B. Marine Bioinvasions in the Mediterranean Sea—History, Distribution and Ecology. In Biological Invasions in Marine Ecosystems; Rilov, G., Crooks, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 549–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahav, E.; Belkin, N.; Nnebuo, O.; Sisma-Ventura, G.; Guy-Haim, T.; Sharon-Gojman, R.; Geisler, E.; Bar-Zeev, E. Jellyfish Swarm Impair the Pretreatment Efficiency and Membrane Performance of Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakar, N.; Disegni, D.; Angel, D. Economic Evaluation of Jellyfish Effects on the Fishery Sector—A Case Study from the Eastern Mediterranean. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual BIOECON Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, 11–13 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, D.L.; Edelist, D.; Freeman, S. Local Perspectives on Regional Challenges: Jellyfish Proliferation and Fish Stock Management along the Israeli Mediterranean Coast. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, A.; Galil, B.; Gowdy, J.; Nunes, P.A. Jellyfish Outbreak Impacts on Recreation in the Mediterranean Sea: Welfare Estimates from a Socioeconomic Pilot Survey in Israel. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 11, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Gofas, S.; Verlaque, M.; Cinar, M.E.; Raso, J.E.G.; Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Azzurro, E.; Bilecenoglu, M.; Froglia, C.; et al. Alien Species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010. A Contribution to the Application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part I. Spatial Distribution. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2010, 11, 381–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Wallentinus, I.; Zenetos, A.; Golani, D. Impacts of Invasive Alien Marine Species on Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity: A Pan-European Review. Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 391–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, B.S.; Mienis, H.K.; Hoffman, R.; Goren, M. Non-Indigenous Species along the Israeli Mediterranean Coast: Tally, Policy, Outlook. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 2011–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, M. Periclimenes nomadophila and Tuleariocaris sarec, Two New Species of Pontoniine Shrimps (Decapoda: Pontoniinae), from Inhaca Island, Mozambique. J. Crustac. Biol. 1994, 14, 782–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahera, Q.; Kazmi, Q.B. Occurrence of Rhopilema nomadica Galil, 1990 (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) in Pakistani Waters. Int. J. Biol. Res. 2015, 3, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Morandini, A.C.; Gul, S. Rediscovery of Sanderia malayensis and Remarks on Rhopilema nomadica Record in Pakistan (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa). Pap. Avulsos Zool. 2016, 56, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, M.D. A Field Guide to the Seashores of Eastern Africa and the Western Indian Ocean Islands, 2nd ed.; SIDA/Department for Research Cooperation, SAREC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.H.; Graham, W.M.; Widmer, C. Jellyfish Life Histories: Role of Polyps in Forming and Maintaining Scyphomedusa Populations. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2012, 63, 133–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Shibata, M.; Makabe, R.; Ikeda, H.; Uye, S.I. Body Size Reduction under Starvation, and the Point of No Return, in Ephyrae of the Moon Jellyfish Aurelia aurita. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 510, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.N.; Jacobs, D.K. Molecular Evidence for Cryptic Species of Aurelia aurita (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa). Biol. Bull. 2001, 200, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

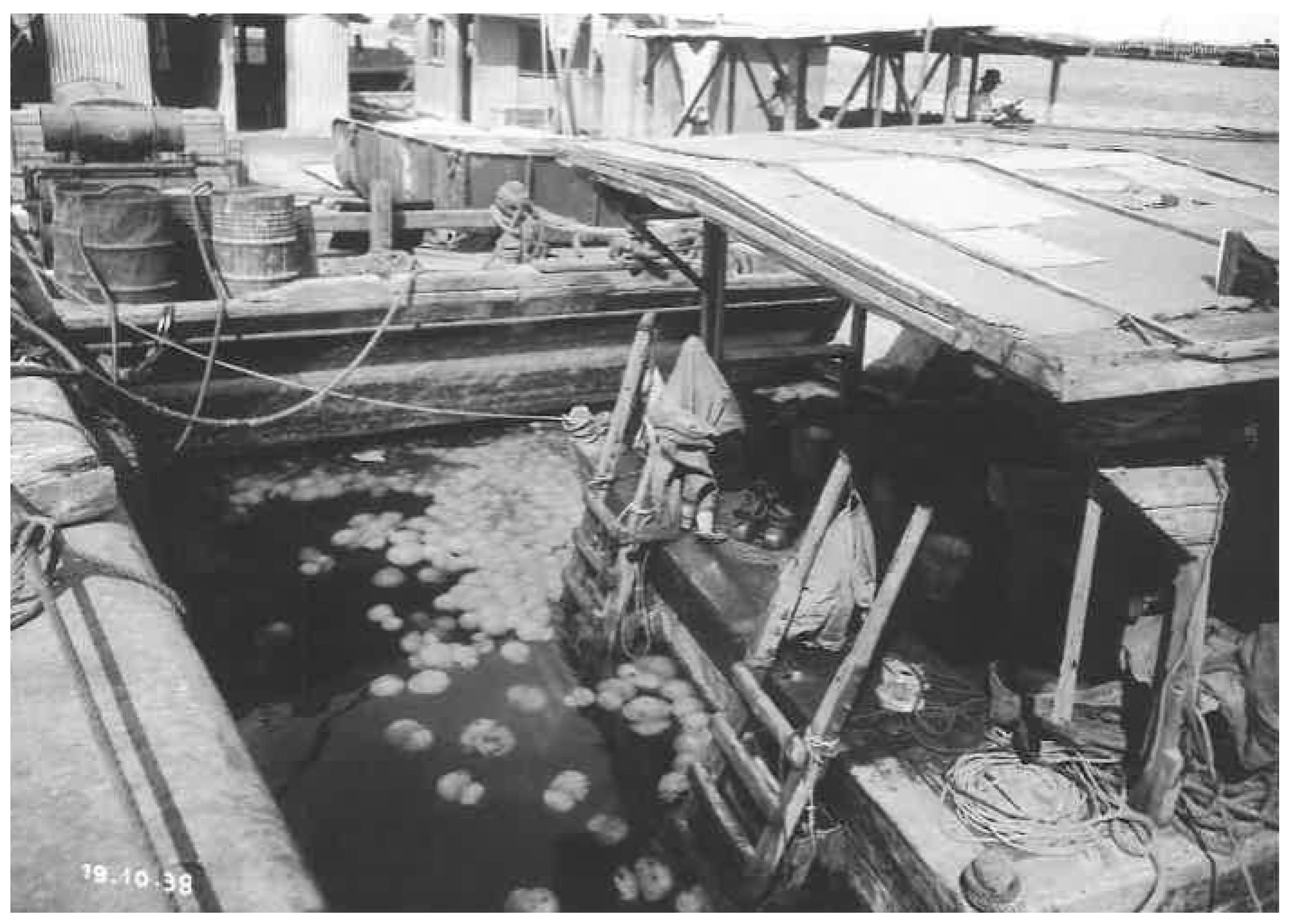

- Nakar, N. Jellyfish Impact on Fisheries and Planula Settlement Dynamics of the Scyphozoan Medusa Rhopilema nomadica on the Mediterranean Coast of Israel. Master’s Thesis, Department of Maritime Civilizations, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.T.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A Fast Online Phylogenetic Tool for Maximum Likelihood Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Nguyen, M.A.T.; Von Haeseler, A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. A Simple, Fast, and Accurate Algorithm to Estimate Large Phylogenies by Maximum Likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003, 52, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More Models, New Heuristics and Parallel Computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefer, S.; Abelson, A.; Mokady, O.; Geffen, E.L.I. Red to Mediterranean Sea Bioinvasion: Natural Drift through the Suez Canal, or Anthropogenic Transport? Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 2333–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safriel, U.N. The “Lessepsian Invasion”—A Case Study Revisited. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 59, 214–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, W.M.; Martin, D.L.; Felder, D.L.; Asper, V.L.; Perry, H.M. Ecological and Economic Implications of a Tropical Jellyfish Invader in the Gulf of Mexico. In Marine Bioinvasions: Patterns, Processes and Perspectives; Pederson, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 5, pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migotto, A.E.; Marques, A.C.; Morandini, A.C.; Silveira, F.L.D. Checklist of the Cnidaria Medusozoa of Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 2002, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini, A.C.; Stampar, S.N.; Maronna, M.M.; Silveira, F.L.D. All Non-Indigenous Species Were Introduced Recently? The Case Study of Cassiopea (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) in Brazilian Waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2017, 97, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.R.; Munoz, S.E.; Vander Zanden, M.J. Outbreak of an Undetected Invasive Species Triggered by a Climate Anomaly. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, D.; Kuplik, Z.; Prieto, L.; Brown, M.; Uye, S.; Doyle, T.; Pitt, K.; Fitt, W.; Gibbons, M. Ecology of Rhizostomeae. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2024, 98, 397–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, O. Die Scyphomedusen der Siboga-Expedition; Buchhandlung und Druckerei Vormals EJ Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelist, D.; Knutsen, Ø.; Ellingsen, I.; Majaneva, S.; Aberle, N.; Dror, H.; Angel, D.L. Tracking Jellyfish Swarm Origins Using a Combined Oceanographic–Genetic–Citizen Science Approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 869619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Mueller-Navarra, D.C.; Hylander, S.; Sommer, U.; Javidpour, J. Food Quality Matters: Interplay among Food Quality, Food Quantity and Temperature Affecting Life History Traits of Aurelia aurita (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) Polyps. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveridge, A.; Lucas, C.H.; Pitt, K.A. Shorter, Warmer Winters May Inhibit Production of Ephyrae in a Population of the Moon Jellyfish Aurelia aurita. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, H.; Angel, D. Rising Seawater Temperatures Affect the Fitness of Rhopilema nomadica Polyps and Podocysts and the Expansion of This Medusa into the Western Mediterranean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2024, 728, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, Y.; Samaan, A.; Zaghloul, F.A. Estuarine Plankton of the Nile and the Effect of Freshwater. In Fresh-Water on the Sea, Proceedings of the Influence of Fresh-Water Outflow on Biological Processes in Fjords and Coastal Waters Symposium; The Association of Norwegian Oceanographers: Oslo, Norway, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf El Din, S.H. Effect of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile Flood and on the Estuarine and Coastal Circulation Pattern along the Mediterranean Egyptian Coast. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azov, Y. Eastern Mediterranean—A Marine Desert? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 23, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, Y. Observations on the Nile Bloom of Phytoplankton in the Mediterranean. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1960, 26, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, A.A.; Dowidar, N. Phytoplankton Production in Relation to Nutrients along the Egyptian Mediterranean Coast. Stud. Trop. Oceanogr. 1967, 5, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Dowidar, N.M. Phytoplankton Biomass and Primary Productivity of the South-Eastern Mediterranean. Deep Sea Res. Part A Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1984, 31, 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, A.A. Effect of River Outflow Management on Marine Life. Mar. Biol. 1972, 15, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoecker, D.; Capuzzo, J.M. Predation on Protozoa: Its Importance to Zooplankton. J. Plankton Res. 1990, 12, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, P. Particle size selection, feeding rates and growth dynamics of marine planktonic oligotrichous ciliates (Ciliophora: Oligotrichina). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1986, 33, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, S.W. Replacing the Nile: Are Anthropogenic Nutrients Providing the Fertility Once Brought to the Mediterranean by a Great River? Ambio 2003, 32, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, T. Planktonic Ciliates as a Food Source for the Scyphozoan Aurelia aurita (s.l.): Feeding Activity and Assimilation of the Polyp Stage. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 407, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, T. Planktonic Ciliates as Food for the Scyphozoan Aurelia aurita (s.l.): Effects on Asexual Reproduction of the Polyp Stage. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2013, 445, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, T. Planktonic Ciliates as Food for the Scyphozoan Aurelia coerulea: Feeding and Growth Responses of Ephyra and Metephyra Stages. J. Oceanogr. 2018, 74, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuplik, Z.; Angel, D.L. Diet Composition and Some Observations on the Feeding Ecology of the Rhizostome Rhopilema nomadica in Israeli Coastal Waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2020, 100, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, F.; Valiente, J.A.; Khodayar, S. A Warming Mediterranean: 38 Years of Increasing Sea Surface Temperature. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiariti, A.; Morandini, A.C.; Jarms, G.; von Glehn Paes, R.; Franke, S.; Mianzan, H. Asexual Reproduction Strategies and Blooming Potential in Scyphozoa. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 510, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, M.; Ohtsu, K.; Uye, S.I. Bloom or Non-Bloom in the Giant Jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae): Roles of Dormant Podocysts. J. Plankton Res. 2013, 35, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, M. Dynamic Model for Life History of Scyphozoa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanos, A.M.; Khafagy, A.A.; Dean, R.G. Protective Works on the Nile Delta Coast. J. Coast. Res. 1995, 11, 516–528. [Google Scholar]

- Frihy, O.E.; Debes, E.A.; El Sayed, W.R. Processes Reshaping the Nile Delta Promontories of Egypt: Pre- and Post-Protection. Geomorphology 2003, 53, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Walraven, L.; van Bleijswijk, J.; van der Veer, H.W. Here Are the Polyps: In Situ Observations of Jellyfish Polyps and Podocysts on Bivalve Shells. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Pitt, K.A.; Lucas, C.H.; Purcell, J.E.; Uye, S.I.; Robinson, K.; Brotz, L.; Decker, M.B.; Sutherland, K.R.; Malej, A.; et al. Is Global Ocean Sprawl a Cause of Jellyfish Blooms? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, K.F. Living with Shore Protection Structures: A Review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2014, 150, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alías, A.; Quispe-Becerra, J.I.; Conde-Caño, M.R.; Marcos, C.; Pérez-Ruzafa, A. Mediterranean Biogeography, Colonization, Expansion, Phenology, and Life Cycle of the Invasive Jellyfish Phyllorhiza punctata von Lendenfeld, 1884. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 299, 108699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Perez, P.; Quispe-Becerra, J.I.; Oliver, J.A.; Marcos, C.; Perez-Ruzafa, A.; Fernández-Alías, A. Colonization of the Mediterranean Sea by the Lessepsian Invasive Jellyfish Cassiopea andromeda (Forskål, 1775)—A Systematic Review. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2025, 26, 714–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippingale, R.J.; Kelly, S.J. Reproduction and Survival of Phyllorhiza punctata (Cnidaria: Rhizostomeae) in a Seasonally Fluctuating Salinity Regime in Western Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1995, 46, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramp, P.L. Zoogeographical Studies on Rhizostomeae (Scyphozoa). Vidensk. Medd. Dansk Naturhist. Foren. 1970, 133, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, M.N.; Hamner, W.M. A Character-Based Analysis of the Evolution of Jellyfish Blooms: Adaptation and Exaptation. Hydrobiologia 2009, 616, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kuplik, Z.; Dror, H.; Tamar, K.; Sutton, A.; Lusana, J.; Lugendo, B.; Angel, D.L. Rhopilema nomadica in the Mediterranean: Molecular Evidence for Migration and Insights into Its Proliferation. Diversity 2026, 18, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020094

Kuplik Z, Dror H, Tamar K, Sutton A, Lusana J, Lugendo B, Angel DL. Rhopilema nomadica in the Mediterranean: Molecular Evidence for Migration and Insights into Its Proliferation. Diversity. 2026; 18(2):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020094

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuplik, Zafrir, Hila Dror, Karin Tamar, Alan Sutton, James Lusana, Blandina Lugendo, and Dror L. Angel. 2026. "Rhopilema nomadica in the Mediterranean: Molecular Evidence for Migration and Insights into Its Proliferation" Diversity 18, no. 2: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020094

APA StyleKuplik, Z., Dror, H., Tamar, K., Sutton, A., Lusana, J., Lugendo, B., & Angel, D. L. (2026). Rhopilema nomadica in the Mediterranean: Molecular Evidence for Migration and Insights into Its Proliferation. Diversity, 18(2), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020094