Management Pathways for Fragmented Populations: From Habitat Restoration to Genetic Intervention

Abstract

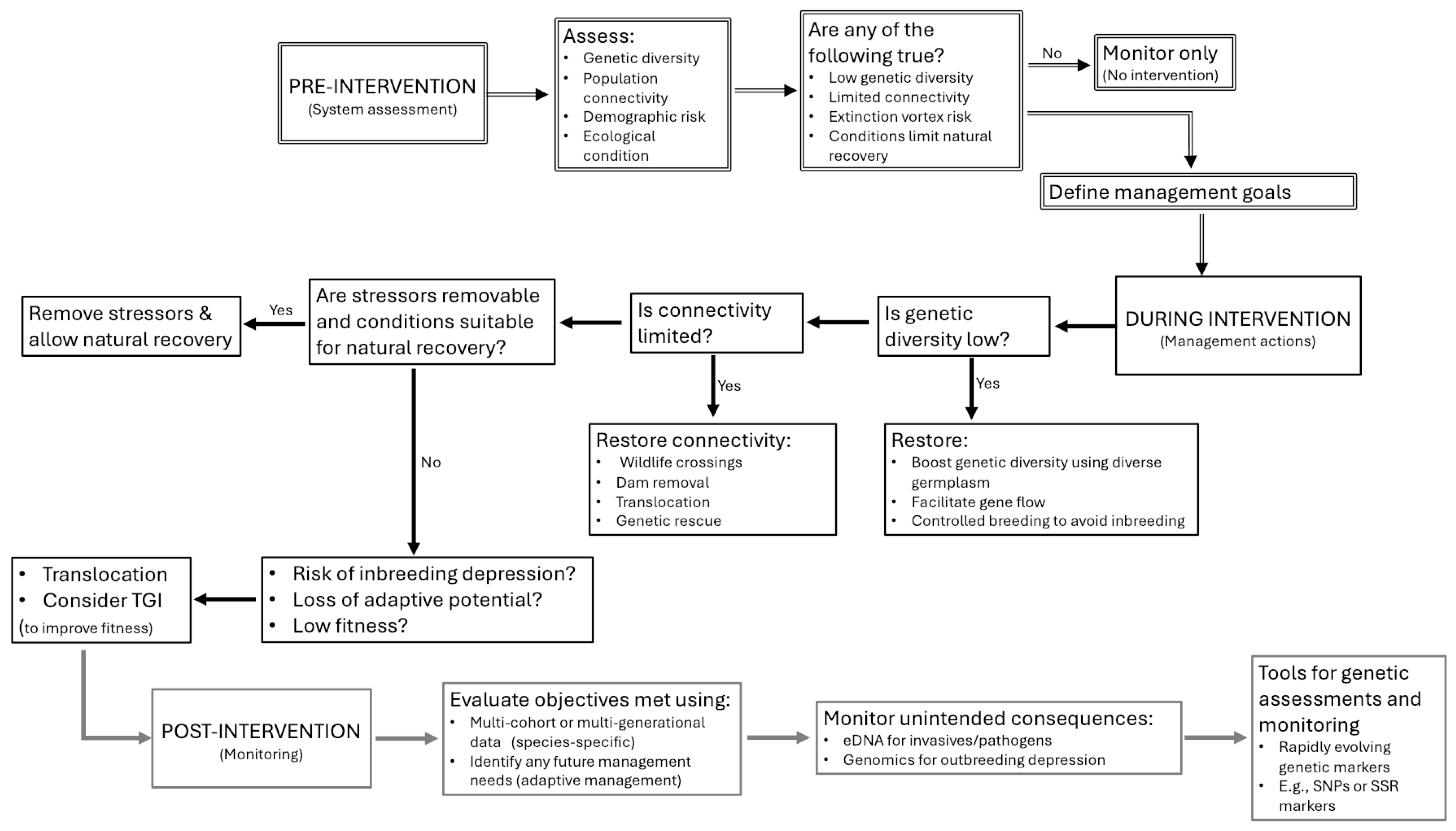

1. Overview

- I.

- Habitat restoration: rebuilding ecological connectivity to allow natural movement and gene flow to resume.

- II.

- Translocation: moving individuals to support demographic stability and bolster genetic variation.

- III.

- Targeted Genetic Intervention: directly facilitating the spread of genetic variants, including through emerging synthetic biology tools.

2. Habitat Fragmentation

2.1. Within-Patch Impacts of Habitat Fragmentation

2.2. Among Patch Impacts of Habitat Fragmentation

3. Genetic Diversity and Evolutionary Potential

4. Habitat Restoration

4.1. Realism Versus Scale in Habitat Restoration

4.2. The Value of Genetic Assessments in Ecological Restoration

5. Translocation

Genetic Surveys to Guide Translocation

6. Targeted Genetic Intervention

6.1. Facilitating the Spread of Adaptive Traits with TGI

6.2. Challenges and Promises for TGI

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ralls, K.; Ballou, J.D.; Dudash, M.R.; Eldridge, M.D.B.; Fenster, C.B.; Lacy, R.C.; Sunnucks, P.; Frankham, R. Call for a Paradigm Shift in the Genetic Management of Fragmented Populations. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, A.S.; Breon, K. The Greatest Threats to Species. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e12670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat Fragmentation and Its Lasting Impact on Earth’s Ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, K.J.J.; Hilbers, J.P.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Graae, B.J.; May, R.; Verones, F.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Schipper, A.M. Habitat Fragmentation Amplifies Threats from Habitat Loss to Mammal Diversity across the World’s Terrestrial Ecoregions. One Earth 2021, 4, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.R.; Klein, C.J.; Halpern, B.S.; Venter, O.; Grantham, H.; Kuempel, C.D.; Shumway, N.; Friedlander, A.M.; Possingham, H.P.; Watson, J.E.M. The Location and Protection Status of Earth’s Diminishing Marine Wilderness. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2506–2512.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, G.; Logez, M.; Xu, J.; Tao, S.; Villéger, S.; Brosse, S. Human Impacts on Global Freshwater Fish Biodiversity. Science 2021, 371, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didham, R.K. Ecological Consequences of Habitat Fragmentation. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, D.A.; Hobbs, R.J.; Margules, C.R. Biological Consequences of Ecosystem Fragmentation: A Review. Conserv. Biol. 1991, 5, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoban, S.; Campbell, C.D.; da Silva, J.M.; Ekblom, R.; Funk, W.C.; Garner, B.A.; Godoy, J.A.; Kershaw, F.; MacDonald, A.J.; Mergeay, J.; et al. Genetic Diversity Is Considered Important but Interpreted Narrowly in Country Reports to the Convention on Biological Diversity: Current Actions and Indicators Are Insufficient. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 261, 109233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laikre, L.; Allendorf, F.W.; Aroner, L.C.; Baker, C.S.; Gregovich, D.P.; Hansen, M.M.; Jackson, J.A.; Kendall, K.C.; McKelvey, K.; Neel, M.C.; et al. Neglect of Genetic Diversity in Implementation of the Convention of Biological Diversity. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeve, M.N. Genetic Diversity Must Be Explicitly Recognized in Ecological Restoration. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 908–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranckx, G.; Jacquemyn, H.; Muys, B.; Honnay, O. Meta-Analysis of Susceptibility of Woody Plants to Loss of Genetic Diversity through Habitat Fragmentation. Conserv. Biol. 2012, 26, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienert, J. Habitat Fragmentation Effects on Fitness of Plant Populations—A Review. J. Nat. Conserv. 2004, 12, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyghobadi, N. The Genetic Implications of Habitat Fragmentation for Animals. Can. J. Zool. 2007, 85, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, I.G.; Allendorf, F.W. How Does the 50/500 Rule Apply to MVPs? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.A.; Monaco, T.A. A Restoration Practitioner’s Guide to the Restoration Gene Pool Concept. Ecol. Restor. 2007, 25, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Rocky Intertidal Invertebrates: The Potential for Metapopulations within and among Shores. In Marine Metapopulations; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 247–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, C.D.; Mora, A.; Wagner, W.L.; Jaramillo, C.A. Testing Geological Models of Evolution of the Isthmus of Panama in a Phylogenetic Framework. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 171, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonlight, P.W.; Richardson, J.E.; Tebbitt, M.C.; Thomas, D.C.; Hollands, R.; Peng, C.-I.; Hughes, M. Continental-Scale Diversification Patterns in a Megadiverse Genus: The Biogeography of Neotropical Begonia. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, H.K.; Luo, D.; Rana, S.K.; Sun, H. Geological and Climatic Factors Affect the Population Genetic Connectivity in Mirabilis Himalaica (Nyctaginaceae): Insight from Phylogeography and Dispersal Corridors in the Himalaya-Hengduan Biodiversity Hotspot. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeve, M.N.; der Stocken, T.V.; Menemenlis, D.; Koedam, N.; Triest, L. Contrasting Effects of Historical Sea Level Rise and Contemporary Ocean Currents on Regional Gene Flow of Rhizophora Racemosa in Eastern Atlantic Mangroves. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raw, J.L.; Van der Stocken, T.; Carroll, D.; Harris, L.R.; Rajkaran, A.; Van Niekerk, L.; Adams, J.B. Dispersal and Coastal Geomorphology Limit Potential for Mangrove Range Expansion under Climate Change. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.R.; Thirumurugan, V.; Bhomia, R.K.; Prabakaran, N. Mangrove Vegetation Response to Alteration in Coastal Geomorphology after an Earthquake in Andaman Islands, India. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 76, 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, T.M.; Zimmerman, R.C.; Engelhardt, K.A.M.; Stevenson, J.C. Twenty-First Century Climate Change and Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in a Temperate Estuary: The Case of Chesapeake Bay. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2017, 3, 1353283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Alleaume, S.; Fortuny, X.; Munoz, F.; Pitard, E. Environmental Factors Governing Spatio-Temporal Series of Aquatic Vegetation in the Bagnas Lagoon. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 319, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, S.; Belliard, J.; Grenouillet, G.; Moatar, F.; Le Pichon, C.; Thieu, V.; Thirel, G.; Jeliazkov, A. The Role of River Connectivity in the Distribution of Fish in an Anthropized Watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 959, 178204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden, Z.D.; Douglas, M.R.; Chafin, T.K.; Douglas, M.E. Riverscape Community Genomics: A Comparative Analytical Approach to Identify Common Drivers of Spatial Structure. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 6743–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit-Bird, K.J. Resource Patchiness as a Resolution to the Food Paradox in the Sea. Am. Nat. 2024, 203, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, P.C.; Boss, E.; Bourdin, G.; Lehahn, Y. Emergent Patterns of Patchiness Differ between Physical and Planktonic Properties in the Ocean. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.L.; Sponaugle, S.; Luo, J.Y.; Gleiber, M.R.; Cowen, R.K. Big or Small, Patchy All: Resolution of Marine Plankton Patch Structure at Micro- to Submesoscales for 36 Taxa. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabk2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, P.; Xiong, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Sun, H.; Li, W.; Chang, J. River Network Connectivity Reductions Dominate Declines in the Richness of Plateau Fish Species Under Climate Change in the Upper Yangtze River Basin. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR037557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieb, E.E.; Eniang, E.A.; Keith-Diagne, L.W.; Carmichael, R.H. In-Water Bridge Construction Effects on Manatees with Implications for Marine Megafauna Species. J. Wildl. Manag. 2021, 85, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatierra, D.; González, M.P.; Blasco, J.; Krull, M.; Araújo, C.V.M. Habitat Loss and Discontinuity as Drivers of Habitat Fragmentation: The Role of Contamination and Connectivity of Habitats. Environ. Res. 2025, 266, 120609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden, Z.D.; Chafin, T.K.; Tiemann, J.S.; Edds, D.R.; Martin, B.T.; Hofmeier, J.; Douglas, M.E.; Douglas, M.R. Historic and Contemporary Selection Define Conservation Units for a Short-Range Endemic within an Anthropogenically-Altered Riverscape. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 62, e03783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, D.R.; Braschler, B.; Rusterholz, H.-P.; Baur, B. Genetic Effects of Anthropogenic Habitat Fragmentation on Remnant Animal and Plant Populations: A Meta-Analysis. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Baldan, D.; Lucas, M.C.; Wang, J.; Rodeles, A.A.; Galib, S.M.; Tao, J.; Li, M.; He, D.; Ding, C. Widespread and Strong Impacts of River Fragmentation by Anthropogenic Barriers on Fishes in the Mekong River Basin. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zheng, R.; He, Y.; Wei, L.; Guan, D.; Motelica-Heino, M.; Xiao, L. Community Structure and Carbon Storage of Mangrove Forests in Hainan Island, China Affected by Their Patch Characteristics. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 90, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodemann, J.R.; James, W.R.; Rehage, J.S.; Furman, B.T.; Pittman, S.J.; Santos, R.O. Response of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Seascapes to a Large-Scale Seagrass Die-off: A Case Study in Florida Bay. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 318, 109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberg, J.; Findlay, S.E.G.; Limburg, K.E.; Diemont, S.A.W. Post-Storm Sediment Burial and Herbivory of Vallisneria Americana in the Hudson River Estuary: Mechanisms of Loss and Implications for Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelena, T.M.; Boylen, C.W.; Nierzwicki-Bauer, S.A. Impacts of Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee on the Ecology of the Hudson River Estuary. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2019, 17, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeve, M.N.; Engelhardt, K.A.M.; Gray, M.; Neel, M.C. Calm after the Storm? Similar Patterns of Genetic Variation in a Riverine Foundation Species before and after Severe Disturbance. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, A.A.A.; Ferraz, K.M.P.M.B.; Magioli, M.; Alexandrino, E.R.; Hasui, É.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Tobias, J.A. Habitat Fragmentation Narrows the Distribution of Avian Functional Traits Associated with Seed Dispersal in Tropical Forest. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, L.; Karubian, J. Habitat Loss and Fragmentation Reduce Effective Gene Flow by Disrupting Seed Dispersal in a Neotropical Palm. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 3055–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, M.S.; Rus, A.I.; Mella, V.S.A.; Krockenberger, M.B.; Lindsay, J.; Moore, B.D.; McArthur, C. Patch Quality and Habitat Fragmentation Shape the Foraging Patterns of a Specialist Folivore. Behav. Ecol. 2022, 33, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.M.; Blowes, S.A.; Knight, T.M.; Gerstner, K.; May, F. Ecosystem Decay Exacerbates Biodiversity Loss with Habitat Loss. Nature 2020, 584, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Pierre, E.; Guisan, A. On the Emergence of Ecosystem Decay: A Critical Assessment of Patch Area Effects across Spatial Scales. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 296, 110674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, K.A.M.; Lloyd, M.W.; Neel, M.C. Effects of Genetic Diversity on Conservation and Restoration Potential at Individual, Population, and Regional Scales. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 179, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingala, M.R.; Becker, D.J.; Bak Holm, J.; Kristiansen, K.; Simmons, N.B. Habitat Fragmentation Is Associated with Dietary Shifts and Microbiota Variability in Common Vampire Bats. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 6508–6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Dong, M. The Diverse Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Plant–Pollinator Interactions. Plant Ecol. 2016, 217, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jump, A.S.; Peñuelas, J. Genetic Effects of Chronic Habitat Fragmentation in a Wind-Pollinated Tree. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8096–8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, C.J.; Beheregaray, L.B. Recent and Rapid Anthropogenic Habitat Fragmentation Increases Extinction Risk for Freshwater Biodiversity. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 2857–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.R.; Burdett, C.L.; Theobald, D.M.; King, S.R.B.; Di Marco, M.; Rondinini, C.; Boitani, L. Quantification of Habitat Fragmentation Reveals Extinction Risk in Terrestrial Mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7635–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Crowther, T.W.; Lauber, T.; Zohner, C.M.; Smith, G.R. A Globally Consistent Negative Effect of Edge on Aboveground Forest Biomass. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 9, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangler, E.S.; Hanson, P.E.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. Interactive Effects of Habitat Fragmentation and Microclimate on Trap-Nesting Hymenoptera and Their Trophic Interactions in Small Secondary Rainforest Remnants. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontúrbel, F.E.; Murúa, M.M. Microevolutionary Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Plant-Animal Interactions. Adv. Ecol. 2014, 2014, 379267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury Morgan, R.; Jucker, T. A Unifying Framework for Understanding How Edge Effects Reshape the Structure, Composition and Function of Forests. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnall, A.H.; Byers, J.E.; Yeager, L.A.; Fodrie, F.J. Comparing Edge and Fragmentation Effects within Seagrass Communities: A Meta-Analysis. Ecology 2022, 103, e3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, W.K.; de Matos, A.C.L.; Zenni, R.D. Habitat Permeability Drives Community Metrics, Functional Traits, and Herbivory in Neotropical Spontaneous Urban Flora. Flora 2024, 319, 152581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ling, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, R.; Wang, Y. How Do Different Processes of Habitat Fragmentation Affect Habitat Quality?—Evidence from China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulting, K.A.; Brudvig, L.A.; Damschen, E.I.; Levey, D.J.; Resasco, J.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Haddad, N.M. Habitat Edges Decrease Plant Reproductive Output in Fragmented Landscapes. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Dirzo, R. Effects of Fragmentation on Pollinator Abundance and Fruit Set of an Abundant Understory Palm in a Mexican Tropical Forest. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschen, E.I.; Baker, D.V.; Bohrer, G.; Nathan, R.; Orrock, J.L.; Turner, J.R.; Brudvig, L.A.; Haddad, N.M.; Levey, D.J.; Tewksbury, J.J. How Fragmentation and Corridors Affect Wind Dynamics and Seed Dispersal in Open Habitats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3484–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafin, T.K.; Zbinden, Z.D.; Douglas, M.R.; Martin, B.T.; Middaugh, C.R.; Gray, M.C.; Ballard, J.R.; Douglas, M.E. Spatial Population Genetics in Heavily Managed Species: Separating Patterns of Historical Translocation from Contemporary Gene Flow in White-Tailed Deer. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeles, A.A.; Galicia, D.; Miranda, R. A Simple Method to Assess the Fragmentation of Freshwater Fish Meta-Populations: Implications for River Management and Conservation. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acre, M.R.; Grabowski, T.B.; Leavitt, D.J.; Smith, N.G.; Pease, A.A.; Pease, J.E. Blue Sucker Habitat Use in a Regulated Texas River: Implications for Conservation and Restoration. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2021, 104, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegscheider, B.; Waldock, C.; Calegari, B.B.; Josi, D.; Brodersen, J.; Seehausen, O. Neglecting Biodiversity Baselines in Longitudinal River Connectivity Restoration Impacts Priority Setting. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 175167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, V.; Schmitt, R.J.P.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Zarfl, C.; King, H.; Schipper, A.M. Impacts of Current and Future Large Dams on the Geographic Range Connectivity of Freshwater Fish Worldwide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 3648–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, C.B.; Fortin, M.-J.; Jackson, D.A.; Lawrie, D.; Stanfield, L.; Shrestha, N. Habitat Alteration and Habitat Fragmentation Differentially Affect Beta Diversity of Stream Fish Communities. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Aguayo, F.; McCracken, G.R.; Manosalva, A.; Habit, E.; Ruzzante, D.E. Human-Induced Habitat Fragmentation Effects on Connectivity, Diversity, and Population Persistence of an Endemic Fish, Percilia Irwini, in the Biobío River Basin (Chile). Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheptou, P.-O.; Hargreaves, A.L.; Bonte, D.; Jacquemyn, H. Adaptation to Fragmentation: Evolutionary Dynamics Driven by Human Influences. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohonak, A.J. Dispersal, Gene Flow, and Population Structure. Q. Rev. Biol. 1999, 74, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, W.H.; Allendorf, F.W. What Can Genetics Tell Us about Population Connectivity? Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 3038–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macarthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The Theory of Island Biogeography; REV-Revised.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967; ISBN 978-0-691-08836-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hanski, I. Metapopulation Ecology; Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-19-854065-6. [Google Scholar]

- Levins, R. Some Demographic and Genetic Consequences of Environmental Heterogeneity for Biological Control. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1969, 15, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatoglu, D.; Lundregan, S.L.; Fetterplace, E.; Goedert, D.; Husby, A.; Niskanen, A.K.; Muff, S.; Jensen, H. The Genetic Basis of Dispersal in a Vertebrate Metapopulation. Mol. Ecol. 2024, 33, e17295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Nukazawa, K.; Resh, V.H.; Watanabe, K. Environmental Effects, Gene Flow and Genetic Drift: Unequal Influences on Genetic Structure across Landscapes. J. Biogeogr. 2023, 50, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics 1931, 16, 97–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatkin, M. Rare Alleles as Indicators of Gene Flow. Evolution 1985, 39, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.V.; Hansson, B.; Patramanis, I.; Morales, H.E.; van Oosterhout, C. The Impact of Habitat Loss and Population Fragmentation on Genomic Erosion. Conserv. Genet. 2024, 25, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitume, E.V.; Bonte, D.; Ronce, O.; Bach, F.; Flaven, E.; Olivieri, I.; Nieberding, C.M. Density and Genetic Relatedness Increase Dispersal Distance in a Subsocial Organism. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, R.S. The Idiot’s Guide to Effective Population Size. Mol. Ecol. 2025, 34, e17670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.H.; Charlesworth, B. Genetic Revolutions, Founder Effects, and Speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984, 15, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, M.; Megens, H.-J.; Derks, M.F.L.; de Cara, Á.M.R.; Groenen, M.A.M. Deleterious Alleles in the Context of Domestication, Inbreeding, and Selection. Evol. Appl. 2019, 12, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; DeWoody, J.A. Genetic Load Has Potential in Large Populations but Is Realized in Small Inbred Populations. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 1540–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnock, M.F.; Teisberg, J.E.; Kasworm, W.F.; Falcy, M.R.; Proctor, M.F.; Waits, L.P. Gene Flow Prevents Genetic Diversity Loss despite Small Effective Population Size in Fragmented Grizzly Bear (Ursus Arctos) Populations. Conserv. Genet. 2025, 26, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Hoban, S.; Hunter, M.; Paz-Vinas, I.; Garroway, C.J. Genetic Diversity and IUCN Red List Status. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal-Pérez, E.J.; Fuchs, E.J.; Martén-Rodríguez, S.; Quesada, M. Habitat Fragmentation Negatively Affects Effective Gene Flow via Pollen, and Male and Female Fitness in the Dioecious Tree, Spondias purpurea (Anacardiaceae). Biol. Conserv. 2021, 256, 109007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuntini, S.; Pedruzzi, L. Sex and the Patch: The Influence of Habitat Fragmentation on Terrestrial Vertebrates’ Mating Strategies. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 35, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. Evolution of the Mutation Rate. Trends Genet. 2010, 26, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniegowski, P.D.; Gerrish, P.J.; Johnson, T.; Shaver, A. The Evolution of Mutation Rates: Separating Causes from Consequences. BioEssays 2000, 22, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, P.W. Gene Flow and Genetic Restoration: The Florida Panther as a Case Study. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 996–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A.A.; Sgrò, C.M.; Kristensen, T.N. Revisiting Adaptive Potential, Population Size, and Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindell, W.R.; Bouzat, J.L. Modeling the adaptive potential of isolated populations: Experimental simulations using drosophila. Evolution 2005, 59, 2159–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- With, K.A.; Gardner, R.H.; Turner, M.G. Landscape Connectivity and Population Distributions in Heterogeneous Environments. Oikos 1997, 78, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalet, C.; De Rochambeau, H. Predicting the Genetic Drift in Small Populations. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1985, 13, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, L.M.; MacKay, I.; Oostra, B.; van Duijn, C.M.; Aulchenko, Y.S. The Effect of Genetic Drift in a Young Genetically Isolated Population. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2005, 69, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beita, C.M.; Murillo, L.F.S.; Alvarado, L.D.A. Ecological Corridors in Costa Rica: An Evaluation Applying Landscape Structure, Fragmentation-Connectivity Process, and Climate Adaptation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, T.L.; Betts, M.G.; Pfeifer, M.; Wolf, C.; Banks-Leite, C.; Barbaro, L.; Barlow, J.; Cerezo, A.; Kennedy, C.M.; Kormann, U.G.; et al. Climate-Driven Variation in Dispersal Ability Predicts Responses to Forest Fragmentation in Birds. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzat, J.L. Conservation Genetics of Population Bottlenecks: The Role of Chance, Selection, and History. Conserv. Genet. 2010, 11, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C.; Quiñones, R.A.; Brante, A.; Hernández-Miranda, E.; Vásquez, C.; Quiñones, R.A.; Brante, A.; Hernández-Miranda, E. Genetic Diversity and Resilience in Benthic Marine Populations. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2023, 96, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated Modern Human–Induced Species Losses: Entering the Sixth Mass Extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.R.; Knowles, L.L. Habitat Corridors Facilitate Genetic Resilience Irrespective of Species Dispersal Abilities or Population Sizes. Evol. Appl. 2015, 8, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tummers, J.S.; Galib, S.M.; Lucas, M.C. Fish Community and Abundance Response to Improved Connectivity and More Natural Hydromorphology in a Post-Industrial Subcatchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-H.; Shih, S.-S.; Otte, M.L. Restoration Recommendations for Mitigating Habitat Fragmentation of a River Corridor. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, D.A.; Gatt, Y.M.; Ahmad, R.; Brown, B.M.; Sidik, F.; Wodehouse, D. Achieving Ambitious Mangrove Restoration Targets Will Need a Transdisciplinary and Evidence-Informed Approach. One Earth 2022, 5, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks-Leite, C.; Ewers, R.M.; Folkard-Tapp, H.; Fraser, A. Countering the Effects of Habitat Loss, Fragmentation, and Degradation through Habitat Restoration. One Earth 2020, 3, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelow, C.A.; Connolly, R.M.; Turschwell, M.P.; Adame, M.F.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Andradi-Brown, D.A.; Bunting, P.; Canty, S.W.J.; Dunic, J.C.; Friess, D.A.; et al. Ambitious Global Targets for Mangrove and Seagrass Recovery. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 1641–1649.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilderbrand, R.H.; Watts, A.C.; Randle, A.M. The Myths of Restoration Ecology. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.A.; Schultz, B.; Ramprasad, V.; Fischer, H.; Rana, P.; Filippi, A.M.; Güneralp, B.; Ma, A.; Rodriguez Solorzano, C.; Guleria, V.; et al. Limited Effects of Tree Planting on Forest Canopy Cover and Rural Livelihoods in Northern India. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltham, N.J.; Elliott, M.; Lee, S.Y.; Lovelock, C.; Duarte, C.M.; Buelow, C.; Simenstad, C.; Nagelkerken, I.; Claassens, L.; Wen, C.K.-C.; et al. UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030—What Chance for Success in Restoring Coastal Ecosystems? Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 00071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration World Restoration Flagships. Available online: https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/world-restoration-flagships (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hemraj, D.A.; Bishop, M.J.; Hancock, B.; Minuti, J.J.; Thurstan, R.H.; Zu Ermgassen, P.S.E.; Russell, B.D. Oyster Reef Restoration Fails to Recoup Global Historic Ecosystem Losses despite Substantial Biodiversity Gain. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabp8747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodikara, K.A.S.; Mukherjee, N.; Jayatissa, L.P.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Koedam, N. Have Mangrove Restoration Projects Worked? An in-Depth Study in Sri Lanka. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.M.; Stewart, A.G. Ecosystem Restoration Is Risky … but We Can Change That. One Earth 2020, 3, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmito, S.D.; Basyuni, M.; Kridalaksana, A.; Saragi-Sasmito, M.F.; Lovelock, C.E.; Murdiyarso, D. Challenges and Opportunities for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals through Restoration of Indonesia’s Mangroves. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, B.G. Grand Challenges in Ecosystem Restoration. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1353829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, E.M.; Mitchell, R.M.; Winkler, D.E. Perspectives on Challenges and Opportunities at the Restoration-Policy Interface in the U.S.A. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.S.; DeMattia, E.A.; Albright, E.; Bromberger, A.F.; Hayward, O.G.; Mackinson, I.J.; Mantell, S.A.; McAdoo, B.G.; McAfee, D.; McCollum, A.; et al. Beyond Despair: Leveraging Ecosystem Restoration for Psychosocial Resilience. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2307082121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeven, D.; Berkhout, E.; Sewell, A.; van der Esch, S. The Global Cost of International Commitments on Land Restoration. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 4864–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktarov, E.; Saunders, M.I.; Abdullah, S.; Mills, M.; Beher, J.; Possingham, H.P.; Mumby, P.J.; Lovelock, C.E. The Cost and Feasibility of Marine Coastal Restoration. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 1055–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mappin, B.; Ward, A.; Hughes, L.; Watson, J.E.M.; Cosier, P.; Possingham, H.P. The Costs and Benefits of Restoring a Continent’s Terrestrial Ecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.J. Setting Effective and Realistic Restoration Goals: Key Directions for Research. Restor. Ecol. 2007, 15, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesapeake Progress Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV). Available online: https://marylandmatters.org/2025/11/03/sav-planting-chesapeake-bay-new-agreement/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Grayson, J.E.; Chapman, M.G.; Underwood, A.J. The Assessment of Restoration of Habitat in Urban Wetlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 43, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A.M.; Felson, A.J.; Friess, D.A. Mangrove Rehabilitation and Restoration as Experimental Adaptive Management. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 00327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijangos, J.L.; Pacioni, C.; Spencer, P.B.S.; Craig, M.D. Contribution of Genetics to Ecological Restoration. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nef, D.P.; Gotor, E.; Wiederkehr Guerra, G.; Zumwald, M.; Kettle, C.J. Initial Investment in Diversity Is the Efficient Thing to Do for Resilient Forest Landscape Restoration. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 3, 615682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, C.E.; Barbier, E.; Duarte, C.M. Tackling the Mangrove Restoration Challenge. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, X.; Guo, F.; Lee, S.Y.; Yang, Z. Mangrove Restoration in China’s Tidal Ecosystems. Science 2024, 385, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadhurst, L.M.; Lowe, A.; Coates, D.J.; Cunningham, S.A.; McDonald, M.; Vesk, P.A.; Yates, C. Seed Supply for Broadscale Restoration: Maximizing Evolutionary Potential. Evol. Appl. 2008, 1, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procaccini, G.; Piazzi, L. Genetic Polymorphism and Transplantation Success in the Mediterranean Seagrass Posidonia Oceanica. Restor. Ecol. 2001, 9, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, B.W.; Ngeve, M.N.; Engelhardt, K.A.M.; Neel, M.C. Assessing the Potential to Extrapolate Genetic-Based Restoration Strategies Between Ecologically Similar but Geographically Separate Locations of the Foundation Species Vallisneria Americana Michx. Estuaries Coasts 2022, 45, 1656–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeve, M.N.; Triest, L. Planted Mangroves Reflect Low Genetic Diversity of Natural Stands in Southern Cameroon. For. Ecol. Manag. 2026, 601, 123318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Fischer, G.A. Using Multiple Seedlots in Restoration Planting Enhances Genetic Diversity Compared to Natural Regeneration in Fragmented Tropical Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 482, 118819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeve, M.N.; Koedam, N.; Triest, L. Genotypes of Rhizophora Propagules from a Non-Mangrove Beach Provide Evidence of Recent Long-Distance Dispersal. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 2, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeunen, G.-J.; Lipinskaya, T.; Gajduchenko, H.; Golovenchik, V.; Moroz, M.; Rizevsky, V.; Semenchenko, V.; Gemmell, N.J. Environmental DNA (eDNA) Metabarcoding Surveys Show Evidence of Non-Indigenous Freshwater Species Invasion to New Parts of Eastern Europe. Metabarcoding Metagenom. 2022, 6, e68575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, J.J.; Tobias, V.D.; Holcombe, E.F.; Karpenko, K.; Huber, E.R.; Goodman, A.C. Leveraging Environmental DNA (eDNA) to Optimize Targeted Removal of Invasive Fishes. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2024, 39, 2378841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabur, I.; Simioniuc, D.P.; Snowdon, R.J.; Cristea, D. Machine Learning Applied to the Search for Nonlinear Features in Breeding Populations. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 876578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachmuth, S.; Capblancq, T.; Prakash, A.; Keller, S.R.; Fitzpatrick, M.C. Novel Genomic Offset Metrics Integrate Local Adaptation into Habitat Suitability Forecasts and Inform Assisted Migration. Ecol. Monogr. 2024, 94, e1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, B.W.; Engelhardt, K.A.M.; Neel, M.C. Genetic Rescue versus Outbreeding Depression in Vallisneria Americana: Implications for Mixing Seed Sources for Restoration. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 167, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.A. When Local Isn’t Best. Evol. Appl. 2013, 6, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, T.; Stille, B.; Shine, R. Inbreeding Depression in an Isolated Population of Adders Vipera berus. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 75, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, T.; Loman, J.; Anderberg, L.; Anderberg, H.; Georges, A.; Ujvari, B. Genetic Rescue Restores Long-Term Viability of an Isolated Population of Adders (Vipera berus). Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R1297–R1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, B.; Scott, J.M.; Carpenter, J.W.; Reed, C. Translocation as a Species Conservation Tool: Status and Strategy. Science 1989, 245, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.D.; Brook, B.W.; Moseby, K.E.; Johnson, C.N. Factors Affecting Success of Conservation Translocations of Terrestrial Vertebrates: A Global Systematic Review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 28, e01630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J.; Menon, V.; Kock, R.; King, T.; Luz, S.; Ashraf, N.V.K.; Soorae, P.S.; Moehrenschlager, A. IUCN Guidelines on Responsible Translocation of Displaced Organisms; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2025; ISBN 978-2-8317-2333-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, C.J.; McLennan, E.A.; Wise, P.; Lee, A.V.; Pemberton, D.; Fox, S.; Belov, K.; Grueber, C.E. Preserving the Demographic and Genetic Integrity of a Single Source Population during Multiple Translocations. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W.F.; Boulton, R.L.; Sunnucks, P.; Clarke, R.H. Are We Adequately Assessing the Demographic Impacts of Harvesting for Wild-Sourced Conservation Translocations? Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhumberg, B.; Tyre, A.J.; Shea, K.; Possingham, H.P. Linking Wild and Captive Populations to Maximize Species Persistence: Optimal Translocation Strategies. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubow, B.C. Optimal Translocation Strategies for Enhancing Stochastic Metapopulation Viability. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacioni, C.; Wayne, A.F.; Page, M. Guidelines for Genetic Management in Mammal Translocation Programs. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 237, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, T.M.; Hauser, C.E.; Possingham, H.P. Minimise Long-Term Loss or Maximise Short-Term Gain? Optimal Translocation Strategies for Threatened Species. Ecol. Model. 2007, 201, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, E.S. Restoration Demography and Genetics of Plants: When Is a Translocation Successful? Aust. J. Bot. 2008, 56, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.C.; Jenkins, K.J.; Happe, P.J.; Manson, D.J.; Griffin, P.C. Post-Release Survival of Translocated Fishers: Implications for Translocation Success. J. Wildl. Manag. 2022, 86, e22192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, F.J.; Fagan, W.F.; Unmack, P.J. Using Survival Analysis to Study Translocation Success in the Gila Topminnow (Poeciliopsis occidentalis). Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerpeter, M.B.; Coates, P.S.; Mathews, S.R.; Lazenby, K.D.; Prochazka, B.G.; Dahlgren, D.K.; Delehanty, D.J. Brood Translocation Increases Post-Release Recruitment and Promotes Population Restoration of Centrocercus Urophasianus (Greater sage-grouse). Ornithol. Appl. 2024, 126, duae013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, F.; Le Pajolec, S.; Godé, C. Assessing Spatial Mating Patterns in Translocated Populations of Campanula glomerata. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 46, e02548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, D.M.; Fischer, J.N.; King, S.N.D.; Greggor, A.L.; Grether, G.F. Pre-Release Experience with a Heterospecific Competitor Increases Fitness of a Translocated Endangered Species. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 307, 111193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warne, R.K.; Chaber, A.-L. Assessing Disease Risks in Wildlife Translocation Projects: A Comprehensive Review of Disease Incidents. Animals 2023, 13, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, B.J.; Phelan, R.; Weber, M.U.S. Conservation Translocations: Over a Century of Intended Consequences. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, F.; Destombes, A.; Raspé, O. Are Large Census-Sized Populations Always the Best Sources for Plant Translocations? Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yackulic, C.B.; Van Haverbeke, D.R.; Dzul, M.; Bair, L.; Young, K.L. Assessing the Population Impacts and Cost-Effectiveness of a Conservation Translocation. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, A.R.; Fitzpatrick, S.W.; Funk, W.C.; Tallmon, D.A. Genetic Rescue to the Rescue. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorato, D.P.; Cunningham, M.W.; Lotz, M.; Criffield, M.; Shindle, D.; Johnson, A.; Clemons, B.C.F.; Shea, C.P.; Roelke-Parker, M.E.; Johnson, W.E.; et al. Multi-Generational Benefits of Genetic Rescue. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.D.; Eldridge, M.D.B.; Lacy, R.C.; Ralls, K.; Dudash, M.R.; Fenster, C.B. Predicting the Probability of Outbreeding Depression. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.; Jolly, C.J.; Indigo, N.; Smart, A.; Webb, J.; Phillips, B. Kenbi Traditional Owners and Rangers No Outbreeding Depression in a Trial of Targeted Gene Flow in an Endangered Australian Marsupial. Conserv. Genet. 2021, 22, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; McMahon, B.J.; Thörn, F.; Rödin-Mörch, P.; Irestedt, M.; Höglund, J. Inbreeding or Outbreeding Depression? How to Manage an Endangered and Locally Adapted Population of Red Grouse Lagopus scotica. bioRxiv 2023. bioRxiv:2023.08.14.552414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummer, J.A.; Booker, T.R.; Matthey-Doret, R.; Nietlisbach, P.; Thomaz, A.T.; Whitlock, M.C. The Immediate Costs and Long-Term Benefits of Assisted Gene Flow in Large Populations. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 36, e13911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, W.C.; McKay, J.K.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Allendorf, F.W. Harnessing Genomics for Delineating Conservation Units. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, B.R.; Lasky, J.R.; Wagner, H.H.; Urban, D.L. Comparing Methods for Detecting Multilocus Adaptation with Multivariate Genotype–Environment Associations. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 2215–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaggio, A.J.; Segelbacher, G.; Seddon, P.J.; Alphey, L.; Bennett, E.L.; Carlson, R.H.; Friedman, R.M.; Kanavy, D.; Phelan, R.; Redford, K.H.; et al. Is It Time for Synthetic Biodiversity Conservation? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oppen, M.J.H.; Oliver, J.K.; Putnam, H.M.; Gates, R.D. Building Coral Reef Resilience through Assisted Evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2307–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosch, T.A.; Waddle, A.W.; Cooper, C.A.; Zenger, K.R.; Garrick, D.J.; Berger, L.; Skerratt, L.F. Genetic Approaches for Increasing Fitness in Endangered Species. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 37, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, M.D.; Liao, W.; Atkinson, C.T.; LaPointe, D.A. Facilitated Adaptation for Conservation—Can Gene Editing Save Hawaii’s Endangered Birds from Climate Driven Avian Malaria? Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, M.; Shafer, A.B.A. The Peril of Gene-Targeted Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, P.W. Conservation Genetics: Where Are We Now? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E.; Hoffman, E.A. Minimizing Genetic Adaptation in Captive Breeding Programs: A Review. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 2388–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A. Captive Breeding Genetics and Reintroduction Success. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 2915–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. The New Frontier of Genome Engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, M.H.; Beever, E.A.; Barbosa, S.; Fitzpatrick, S.W.; Fletcher, N.K.; Mittan-Moreau, C.S.; Reid, B.N.; Campbell-Staton, S.C.; Green, N.F.; Hellmann, J.J. Understanding Local Adaptation to Prepare Populations for Climate Change. BioScience 2023, 73, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, J.F.; Emmel, A.; Wiedenheft, B.; Sandler, R.L.; Redford, K.H.; Schultz, C.A.; Moehrenschlager, A.; Mark-Shadbolt, M.; Kamau, W.S.; Helm, J.E.; et al. Synthetically Assisted Conservation and the Application of Emerging Biological Technologies for the Protection of Biodiversity. Conserv. Lett. 2025, 18, e13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Gambhir, G.; Dass, A.; Tripathi, A.K.; Singh, A.; Jha, A.K.; Yadava, P.; Choudhary, M.; Rakshit, S. Genetically Modified Crops: Current Status and Future Prospects. Planta 2020, 251, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redford, K.H.; Adams, W.; Carlson, R.; Mace, G.M.; Ceccarelli, B. Synthetic Biology and the Conservation of Biodiversity. Oryx 2014, 48, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleves, P.A.; Tinoco, A.I.; Bradford, J.; Perrin, D.; Bay, L.K.; Pringle, J.R. Reduced Thermal Tolerance in a Coral Carrying CRISPR-Induced Mutations in the Gene for a Heat-Shock Transcription Factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 28899–28905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosch, T.A.; Silva, C.N.S.; Brannelly, L.A.; Roberts, A.A.; Lau, Q.; Marantelli, G.; Berger, L.; Skerratt, L.F. Genetic Potential for Disease Resistance in Critically Endangered Amphibians Decimated by Chytridiomycosis. Anim. Conserv. 2019, 22, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, A.E.; Powell, W.A. Intentional Introgression of a Blight Tolerance Transgene to Rescue the Remnant Population of American Chestnut. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Chestnut Foundation. Available online: https://tacf.org/darling-58/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Waltz, E. Gene-Edited CRISPR Mushroom Escapes US Regulation. Nature 2016, 532, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, R.N.; Jacobs, A.; Wilder, A.P.; Therkildsen, N.O. A Beginner’s Guide to Low-Coverage Whole Genome Sequencing for Population Genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 5966–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrico, B.M.; Capblancq, T.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Keller, S.R. Reciprocal Evaluation of Genomic Offset Predictions of Climate Maladaptation with Independent Empirical Datasets. Am. Nat. 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearse, D.E. Saving the Spandrels? Adaptive Genomic Variation in Conservation and Fisheries Management. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 89, 2697–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, M.; Husby, A.; McFarlane, S.E.; Qvarnström, A.; Ellegren, H. Whole-Genome Resequencing of Extreme Phenotypes in Collared Flycatchers Highlights the Difficulty of Detecting Quantitative Trait Loci in Natural Populations. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2016, 16, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csilléry, K.; Rodríguez-Verdugo, A.; Rellstab, C.; Guillaume, F. Detecting the Genomic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation and the Role of Epistasis in Evolution. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartfield, M.; Glémin, S. Hitchhiking of Deleterious Alleles and the Cost of Adaptation in Partially Selfing Species. Genetics 2014, 196, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.K.; Dunn, S.L.; Gendron, W.A.C.; Helm, J.E.; Kamau, W.S.; Mark-Shadbolt, M.; Moehrenschlager, A.; Redford, K.H.; Russell, G.; Sandler, R.L.; et al. Principles for Introducing New Genes and Species for Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, K.; Brooks, T.; Macfarlane, N.B.W.; Adams, J.S.; Alphey, L.; Bennet, E.; Delborne, J.; Eggermont, H.; Esvelt, K.; KinGirl, A.; et al. Genetic Frontiers for Conservation: An Assessment of Synthetic Biology and Biodiversity Conservation; Technical Assessment; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019; p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Agrees First Global Policy on Synthetic Biology—News|IUCN. Available online: https://iucn.org/news/202510/iucn-agrees-first-global-policy-synthetic-biology (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Hoban, S.; Archer, F.I.; Bertola, L.D.; Bragg, J.G.; Breed, M.F.; Bruford, M.W.; Coleman, M.A.; Ekblom, R.; Funk, W.C.; Grueber, C.E.; et al. Global Genetic Diversity Status and Trends: Towards a Suite of Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) for Genetic Composition. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1511–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S.P.; Forester, B.R.; Latch, E.K.; Aitken, S.N.; Hoban, S. Guidelines for Planning Genomic Assessment and Monitoring of Locally Adaptive Variation to Inform Species Conservation. Evol. Appl. 2018, 11, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stem, C.; Margoluis, R.; Salafsky, N.; Brown, M. Monitoring and Evaluation in Conservation: A Review of Trends and Approaches. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milt, A.W.; Diebel, M.W.; Doran, P.J.; Ferris, M.C.; Herbert, M.; Khoury, M.L.; Moody, A.T.; Neeson, T.M.; Ross, J.; Treska, T.; et al. Minimizing Opportunity Costs to Aquatic Connectivity Restoration While Controlling an Invasive Species. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Habitat Restoration | Translocation | Targeted Genetic Intervention (TGI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Re-establish ecological connectivity to facilitate natural demographic recovery. | Deliberate movement of organisms to facilitate gene flow, provide demographic support, and genetic rescue of imperiled populations. | Directly alter allele frequencies through synthetic biology to increase fitness against specific threats or restore lost diversity. |

| Spatial and temporal Scales | Landscape level, long-term (decades to centuries). | Population level, medium-term (years to decades). | Individual/gene level, potentially rapid intergenerational change. |

| Relative Cost | Very high (land acquisition, earthworks, long-term maintenance). | Moderate to high (capture, transport, monitoring, disease screening). | High initial R&D, potentially lower long-term cost if self-sustaining. |

| Key Feasibility Challenges | Land ownership, political will, conflicts of interest, scale mismatch due to fragmentation, and a long time lag for genetic effects. | Finding suitable and sufficient source populations, logistical complexity of capture/transport. | Lack of genomic resources for non-model species, technical difficulty, regulatory hurdles, and public acceptance. |

| Primary Risks | Ineffective if populations are already genetically depauperate; may facilitate the spread of invasive species. | Outbreeding depression, disease transmission, genetic swamping, and demographic impact on the source population. | Off-target effects, unintended ecological consequences (pleiotropy), escape of modified genes, and ethical concerns. |

| Essential Genetic Information | Landscape genomics to prioritize corridors; pre- and post-monitoring of genetic diversity and connectivity. | Genomic assessment of divergence and local adaptation (GEA) to mitigate outbreeding depression risk. | Whole-genome sequencing, identification of adaptive loci (GEA), functional validation, and off-target analysis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ngeve, M.N.; Rufo, K.E.; Zbinden, Z.D. Management Pathways for Fragmented Populations: From Habitat Restoration to Genetic Intervention. Diversity 2026, 18, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020073

Ngeve MN, Rufo KE, Zbinden ZD. Management Pathways for Fragmented Populations: From Habitat Restoration to Genetic Intervention. Diversity. 2026; 18(2):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020073

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgeve, Magdalene N., Kyle E. Rufo, and Zachery D. Zbinden. 2026. "Management Pathways for Fragmented Populations: From Habitat Restoration to Genetic Intervention" Diversity 18, no. 2: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020073

APA StyleNgeve, M. N., Rufo, K. E., & Zbinden, Z. D. (2026). Management Pathways for Fragmented Populations: From Habitat Restoration to Genetic Intervention. Diversity, 18(2), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020073