Ecology, Distribution, and Conservation Considerations of the Oak-Associated Moth Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scope, Sources, Methods, and Limitations of the Review

3. Taxonomic and Morphological Overview

3.1. Taxonomic History and Current Status

3.2. Diagnostic Adult Morphology

3.3. Genitalic Characters

3.4. Immature Stages

4. Biology and Ecology

4.1. Phenology and Voltinism

4.2. Adult Behaviour and Activity

4.3. Larval Host Plants and Feeding Ecology

4.4. Larval Behaviour and Development

4.5. Habitat Associations

4.6. Summary of Ecological Knowledge and Uncertainties

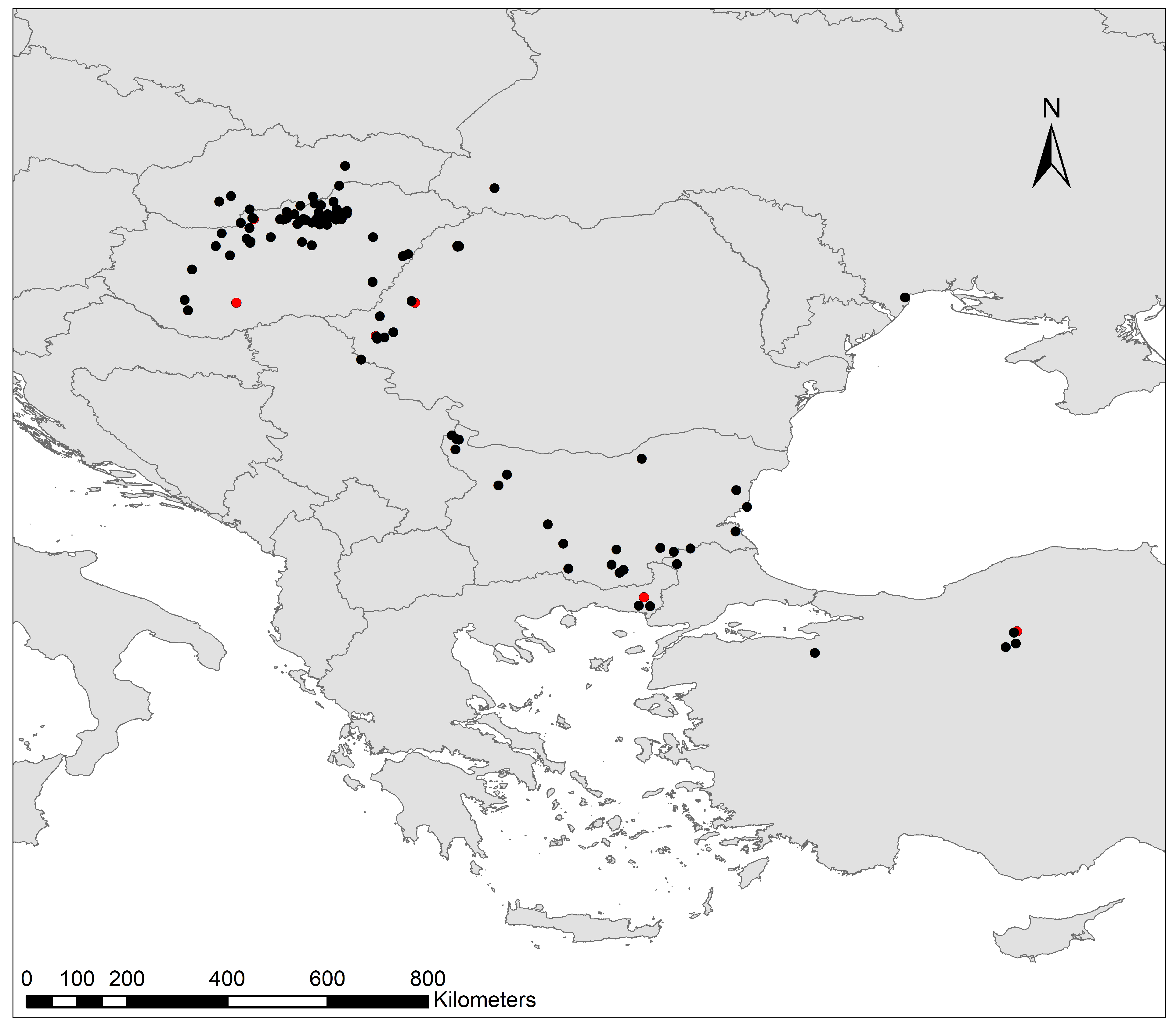

5. Distribution and Biogeography

5.1. Central and Eastern Europe

5.2. Balkan Peninsula

5.3. Türkiye and Asia Minor

5.4. Distributional Synthesis

6. Conservation Status, Threats, and Management Implications

6.1. Conservation Status and Legal Recognition

6.2. Habitat Associations and Vulnerability

6.3. Host Plant Phenology and Climatic Sensitivity

6.4. Data Limitations and Monitoring Challenges

6.5. Conservation Implications and Management Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Original Description and Translation of the Imago (Diószeghy, 1935)

| Die kleinste Art des Genus. Spannweite 23–27, selten 30 mm. Durchschnittlich kleiner als M. pulverulenta, aber robuster gebaut, steht der viel größeren M. stabilis am nächsten. Stirnschöpfe vorspringend, die Ästchen der männlichen Fühler kürzer, Thorax und Abdomen breit, letzteres kurz. Die Vfl. breit, am Apax fein abgerundet, der Außenrand gerade. Grundfarbe und Zeichnung der glatten Vfl. äußerst beständig. Erstere graulich fahlgelb, gleichmäßig mit sehr feinen, graubraunen, nie schwarzen, Atomen bestreut, so daß der Gesamteindruck rehbraun ist. Die beiden Querlinien fehlen meist gänzlich, wo sie aber doch eben noch bemerkber sind (nur bei den etwas lichteren ♀♀) sind sie gleichmäßig fein verlaufend, und nirgend schärfer ausgeprägt. Die Antemediane zieht, wenn vorhanden, von der Costa gerade bis an die obere Mittelzellader, von dort gebrochen in der Richtung des Analwinkels bis zur Falte, dann gerade bis zur zweiten Radiale, von wo sie etwas auswärts laufend den Innenrand erreicht. Die Postmediane ist, wenn vorhanden, ebenfalls fein gezeichnet, sehr feinzähnig, sie kommt der Nierenmakel viel näher als dies bei pulverulenta der Fall ist. Auch diese Linie ist nirgend kräftiger markiert. | The smallest species of the genus. Wingspan 23–27, rarely 30 mm. On average, smaller than M. pulverulenta, but more robustly built, and closest to the much larger M. stabilis. Frontal tufts projecting; branches of the male antenna shorter. Thorax and abdomen broad, the latter short. Forewings broad, apex finely rounded, outer margin straight. Ground colour and markings of the smooth forewings are extremely constant. Ground colour grayish pale yellow, evenly dusted with very fine gray-brown, never black, atoms, so that the overall impression is fawn-brown. The two transverse lines are usually completely absent; where they can still be detected (only in somewhat lighter females), they run evenly fine and are nowhere strongly expressed. The antemedian, if present, runs from the costa straight to the upper median vein, then broken toward the anal angle to the fold, then straight to the second radial, from where it runs slightly outward to the inner margin. The postmedian, if present, is likewise finely drawn, very finely toothed, and lies much closer to the reniform spot than is the case in pulverulenta. This line is also nowhere more strongly marked. |

| Die lichtgelbe Subterminale ist in der Form ähnlich der von pulverulenta aber ganz zusammenhängend, mit dem Saume gleichlaufend, fein, scharf, viel weniger gezähnt und im Analwinkel am kräftigsten gezeichnet. Die Ring- und Nierenmakel sind größer als bei pulverulenta, aber kleiner als bei stabilis, fein, scharf lichtgelb umrandet, voneinander ziemlich weit entfernt. Sie heben sich sehr scharf von der glatten, etwas seidenglänzenden, rehbraunen Grundfarbe ab, und sind in der Regel nicht dunkler ausgefüllt, nur bei manchen ♀♀ ist der untere Teil der Nierenmakel etwas dunkler gefärbt. Die Saumpunkte sind fein schwarz, kaum bemerkbar, die Fransenbasis scharf lichtgelb, der Raum zwischen dieser und der Subterminale etwas dunkler als die Grundfarbe. | The pale yellow subterminal line is similar in shape to that of pulverulenta, but entirely continuous, running parallel to the margin, fine and sharp, much less toothed, and most strongly marked at the anal angle. The orbicular and reniform spots are larger than in pulverulenta but smaller than in stabilis, finely and sharply outlined in pale yellow, set rather far apart. They stand out sharply against the smooth, slightly silky-shining fawn-brown ground colour, and are usually not darker inside, though in some females the lower part of the reniform spot is somewhat darker. Marginal dots fine, black, barely visible; basal fringe sharply pale yellow, the space between this and the subterminal line somewhat darker than the ground colour. |

| Die Hfl.-Grundfarbe ist fahlgelblich, leicht rosenrot angehaucht, vom Saume wurzelwärts 2 mm breit rehbraun, vom Analwinkel läuft nach oben verschwindend eine feine lichte Linie. Hinter dem sehr schwach gezeichneten Mittelmond zieht mit dem Saume parallel eine nur auf den Rippen angedeutete Linie. | Hindwing ground colour pale yellowish with a slight rosy flush; a 2 mm broad fawn-brown border runs inwards from the margin, from the anal angle a fine pale line runs upward, disappearing. Behind the very faintly marked discal spot runs a line parallel to the margin, indicated only on the veins. Fringes are light grey-brown with a faint rosy tone. |

| Fransen licht graubraun mit leicht rosigem Farbenton. Unterseite mit Ausnahme des Vfl.-Innenrandes—der glänzend weißlich ist—rauchgelb. Der Mittelfleck der Vfl. ein verwaschenes dunkles Fleckchen, die Postmediane eine sehr feine dunkle Linie, die auch auf den Hfl. weiterläuft. Der Raum von dieser bis zu den Fransen dunkler graubraun. Der Mittelfleck der Hfl. ein scharfer schwarzer Punkt. Das Ei ist ähnlich jenem von stabilis. aber kleiner, runder, grünlichweiß. Die Mycrophyle nur wenig eingedrückt, und die vielen, von hier auslaufenden Kanälchen, bestehen aus vielen kleinen Grübchen. Ein Fleck an der Mycropvle und der Ringstreifen sind lebhaft rostbraun. Vor dem Ausschlüpfen der Raupe wird das Ei rötlichviolettgrau. | Underside smoky yellow except for the inner margin of the forewing, which is glossy whitish. Median spot of forewing is a diffuse dark speck; postmedian is a very fine dark line, which continues onto the hindwing. The space from this to the fringes darker grey-brown. Median spot of hindwing a distinct black point. The egg resembles that of stabilis but is smaller, rounder, greenish white. The micropyle only slightly depressed; the many radiating channels appear as small pits. A spot at the micropyle and the encircling ring band are bright rust-brown. Before larval emergence, the egg becomes reddish violet-grey. |

| Die Raupe ist in ihren ersten Stadien grünlichgrau, mit spärlichen schwarzen Punkten, in welchen feine Haare stehen. Halsplate braunschwarz, Kopf glänzend schwarz. Futterpflanze Acer-Arten, nicht Eiche. Die weitere Entwickelung konnte nicht verfolgt werden, da die Raupen infolge mangelhafter Pflege eingingen. | The larva in its early stages is greenish-grey, with sparse black dots bearing fine hairs. Cervical plate brown-black; head glossy black. Food plants: Acer species, not oak. Further development could not be followed, as the larvae perished from inadequate care. |

| Die neue Art habe ich aus Puppen (14) gezogen, welche ich am Fuße einer Platane—Platanus orientalis—nahe beieinander aus der Erde gegraben. | The new species I obtained from pupae (14 in number), which I dug from the ground close together at the base of an oriental sycamore (Platanus orientalis). |

Appendix B. Description of the Subspecies Dioszeghyana schmidtii Var. pinkerii (Hreblay, 1993)

| Die beschriebene Unterart stimmt in ihrem Aufbau und den Zeichnungselementen mit schmidtii schmidtii überein. Die Farbe der Vorderflügel und des Körpers ist rötlich, wobei verschiedene Tönungen auftreten können. Die beschriebene Unterart unterscheidet sich von der Stammform in ihrer Farbe. | The described subspecies agrees in its structure and pattern elements with schmidtii schmidtii. The color of the forewings and body is reddish, with various shades possible. The described subspecies differs from the nominate form in its color. |

| Die Charakterisierung der Genitalien.—Beim Männchen stimmt die Struktur des Fangapparates mit jenem von schmidtii schmidtii überein. Das mittlere Diverticulum der Vesica ist kleiner als bei der Stammform. Der Genitalaufbau des Weibchen stimmt mit jenem der Stammform im wesentlichen überein, unterscheidet sich nur im schmaleren Ductus bursae, im größeren Ausschnitt der ventralen Lamelle des Ostium und im größeren Anhang vom VIII. Sternit. | Characterization of the genitalia.—In the male, the structure of the clasping apparatus agrees with that of schmidtii schmidtii. The median diverticulum of the vesica is smaller than in the nominate form. The female genital structure essentially agrees with that of the nominate form, differing only in the narrower ductus bursae, the larger incision of the ventral lamella of the ostium, and the larger appendix of the VIIIth sternite. |

Appendix C. Original Description and Translation of Larval Stages (König, 1971)

| Da schmidtii eher mit cruda verwechselt werden kann, züchtete ich beide Arten parallel. Form und Größe der Eier von schmidtii und cruda sind zum Verwechseln ähnlich, auch die Farbe ist identisch, doch scheint der unregelmäßige Ringstreifen bei schmidtii etwas rötlicher zu sein. Durchmesser der Eier 0.7 mm, Eihöhe 0.4 mm, die Form weit nicht so flachgedrückt wie bei DÖRINGs Abbildung 545. Längsrippen bei schmidtii 40–45, bei cruda 45–50, Netzstruktur kaum zu unterscheiden. Die 10–15 Querrippen sind nur oben klar und werden abwärts immer undeutlicher. Eiboden glatt, etwas gerunzelt. Die Eier werden dicht nebeneinander in 2–3 Spiegelschichten abgelegt. Sie sind sehr schwach angekittel und springen beim Ablösen wie Perlen in allen Richtungen. Die Eischale ist sehr dünn und zerbrechlich. Das Verfärben beginnt nach 10–12 Tagen. | Because schmidtii can easily be confused with cruda, I reared both species in parallel. Form and size of the eggs are almost indistinguishable, also the colour identical, but the irregular encircling band in schmidtii seems somewhat more reddish. Diameter of eggs 0.7 mm, height 0.4 mm, not as flattened as in Döring’s figure 545. Longitudinal ridges in schmidtii 40–45, in cruda 45–50, reticulation scarcely distinguishable. The 10–15 transverse ridges are only clear at the top, becoming less distinct downward. Egg base smooth, somewhat wrinkled. Eggs are deposited closely together in 2–3 overlapping layers. They are only very weakly attached and scatter in all directions when detached, like pearls. Eggshell very thin and fragile. Colour change begins after 10–12 days. |

| Die Räupchen schlüpfen fast gleichzeitig nach 12–16 Tagen je nach Witterungsverhältnissen. Die verlassene Eischale ist hyaline, ohne Pigmentgürtel. DIÖSZEGHY beschrieb die Eiraupe wie folgt: “… in ihren ersten Ständen grünlichgrau mit spärlichen schwarzen Punkten, in welchen feine Haare stehen. Halsplatte braunschwarz. Kopf glänzend schwarz. Futterpflanze Acer-Arten, nicht Eiche (!)”. Diese Beschreibung paßt allerdings auf fast alle Noctuiden-Eiraupen. Nach dem Schlüpfen sind sie sehr flink und tasten unruhig nach Futter umher. Meine Räupchen wollten aber von Acer-Arten nichts wissen, versteckten sid1 dagegen ra~ch in halbgeöffneten Eichenknospen, die sie bald mit feinen Fäden versponnen haben. Also doch Eiche! | The young larvae hatch almost simultaneously after 12–16 days, depending on weather conditions. The empty eggshell is hyaline, without pigment belt. Diószeghy described the first instar larva as: “… in its first stages greenish-grey with sparse black dots bearing fine hairs. Cervical shield brown-black, head glossy black. Food plant Acer species, not oak (!).” This description, however, could apply to almost any noctuid neonate. After hatching, the larvae are very active and restlessly search for food. My larvae, however, refused Acer leaves, and instead quickly hid inside half-opened oak buds, which they soon spun together with silk–thus, oak after all! |

| Bis zur ersten Häutung-welche nach 3–4 Tagen erfolgt-werden zunächst die Herzblätter der Knospen verzehrt. Nach der ersten Häutung bekommen die Raupen ein recht buntes Aussehen und sind von cruda-Raupen sofort zu unterscheiden. Grund farbe schwärzhchgrau, Rütckenlinie zitronengelb, Bauchseite grünlichgelb. Die dunkle Oberseite des Körpers ist von der helleren Unterseite auf jedem Segment einer gekrümmten Linie entlang scharf getrennt. Halsschild schwarz gerandet mit zitronen gelbem Mittelfeld. Die schwarzen Haarwarzen sind ebenfalls zitronengelb umzogen. Die Kopfzeichnung der Raupen ist aufierordentlich kompliziert. Sie besteht aus dunkelbraunen und schwarzen zerrissenen Flecken auf rostbrauner Grundfarbe. Augen und Haarwarzen schwarz. Die hier beschriebene Farben- und Musterzusam· mensetzung bleibt bis zur vollen Entwicklung unverändert. | Until the first instar (after 3–4 days), they feed initially on the inner bud leaves. After the first instar the larvae acquire a very colourful appearance and can immediately be distinguished from cruda. Ground colour dark greyish, dorsal line lemon-yellow, ventral side greenish-yellow. The dark dorsal surface is sharply divided from the lighter ventral side on each segment by a curved line. Prothoracic shield black-edged with a lemon-yellow centre. The black pinacula likewise ringed with lemon-yellow. The head pattern of the larvae is extremely complex, consisting of dark brown and black torn markings on a rusty-brown ground. Ocelli and pinacula are black. This colour and pattern combination remains unchanged through development. |

| Die Lebensweise der Raupen scheint in der Natur interessant zu sein, denn ich stieß auf manche Schwierigkeiten. Die angegriffenen Eichenknospen trockneten rasch ein. In der Natur entwickeln sich die äußeren Blätter, obwohl sie immer versponnen werden, verhältnismäßig rasch weiter und werden von den Raupen durch Fensterfraß angenagt. Die Zucht verlief bis zur dritten Häutung fast verlustlos, die Raupen wurden Jedoch immer unruhiger. Sie verließen häufig die Futterpflanze. deren Blätter später nicht mehr versponnen werden, und rannten im Raupenkasten umher. Ich dachte zunächst an die Notwendigkeit eines einfachen Futterwechsels und reichte ihnen Ahorn, Linde und Ulme. Nach einigen hastigen Bissen wendeten sie sich aber ab und suchten weiter. Im Raupenkasten stand auch ein Gefäß mit Pappelzweigen, auf welchen ich junge Sm. ocellata Räupchen züchtete. Ich bemerkte schon früher, daß diese ohne einen sichtbaren Grund immer weniger wurden, bis ich an einem Morgen eine schmidtii Raupe beim Verzehren einer ocellata überraschte. Kannibalismus ist bei allen Orthosia-Arten beobachtet worden, doch konnte ich ein gegenseitiges Angreifen der schmidtii-Raupen nicht bemerken. Im nächsten Jahr züchtete ich wieder mehrere schmidtii-Raupen in einem engeren Obstglas, wo sie sich dann tatsächlich beim Begegnen gegenseitig angegriffen haben. Die Mordlust der Raupen scheint mit dem Alter anzuwachsen, denn die Unruhe ging so weit, daß viele Raupen eingingen, weil sie keine Blätter mehr annehmen wollten. Die Entdeckung kam zu spät, so erreichten, aus über 100 Jungraupen nur 7 die letzte Häutung und verpuppten sich nur zwei. Die Entwicklug der Raupen dauert 6 Wochen. | The larvae’s behaviour in nature seems interesting, because I encountered difficulties. The attacked oak buds dried quickly. In nature, the outer bud leaves, although always spun together, continue to develop relatively rapidly and are window-fed by the larvae. The rearing went smoothly until the third instar, but then the larvae became increasingly restless, often leaving the food plant, later no longer spinning the leaves, and running about the breeding container. I thought at first they needed a change in food and offered maple, linden, and elm. After a few hasty bites, they turned away and searched further. In the container, there was also a vessel with poplar twigs, on which I was rearing young Smerinthus ocellata larvae. I had already noticed these were dwindling for no clear reason, until one morning I caught a schmidtii larva devouring one. Cannibalism has been observed in all Orthosia species, but I did not notice mutual attacks among schmidtii larvae at first. The next year, I reared several more schmidtii larvae in a smaller jar, where they indeed attacked one another upon contact. Their aggressiveness seems to increase with age, for their restlessness became so great that many perished because they would no longer accept leaves. The discovery came too late, so that of over 100 hatchlings, only 7 reached the final instar, and only 2 pupated. Larval development lasts six weeks. |

| Die Verpuppung erfolgt meinem Erdkokon in 10–15 cm Tiefe. Die gedrungene Puppe läßt sich von derjenigen der cruda kaum unterscheiden, die zwei nach unten gebogenen Kremasterdornen sind bei schmidtii kürzer und stumpfer. Die Puppe überwintert, die Falter schlüpfen zwischen dem 20. III. und 25. IV. Sie lassen sich von cruda durch ihre rehbraune Farbe, gedrungeneren Körperbau, stabilis ähnlichere Vorderflügel-Zeichnung und die asymmetrischen Fühlerglieder leicht unterscheiden. Letzter Körperring der schmidtii-Weibchen ist nicht Jegerohrartig verlängerl wie bei cruda. Die ebenfalls von cruda und auch von stabilis wesentlich abweichenden Genitalien wurden von ISSEKUTZ (1955) und CAPUSE (1965) beschrieben und abgebildet. | Pupation takes place in a cocoon in the earth 10–15 cm deep. The compact pupa is scarcely distinguishable from that of cruda, but the two downward-curved cremaster spines are shorter and blunter in schmidtii. The pupa overwinters, and the moths emerge between 20 March and 25 April. They can be distinguished from cruda by their fawn-brown colour, more compact body, forewing pattern more similar to stabilis, and the asymmetrical antennal segments. The last abdominal segment of the schmidtii female is not earlike prolonged as in cruda. The genitalia, also differing distinctly from those of cruda and stabilis, were described and figured by Issekutz (1955) and Căpușe (1965). |

References

- Kitching, I.J. An Historical Review of the Higher Classification of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera). Bull. Br. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1984, 49, 153–234. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, R.L.H. Towards a Functional Resource-based Concept for Habitat: A Butterfly Biology Viewpoint. Oikos 2003, 102, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerville, K.S.; Ritter, L.M.; Crist, T.O. Forest Moth Taxa as Indicators of Lepidopteran Richness and Habitat Disturbance: A Preliminary Assessment. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 116, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, N.; Kaitala, V.; Komonen, A.; Kotiaho, J.S.; Päivinen, J. Ecological Determinants of Distribution Decline and Risk of Extinction in Moths. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.M.; Kawahara, A.Y.; Daniels, J.C.; Bateman, C.C.; Scheffers, B.R. Climate Change Effects on Animal Ecology: Butterflies and Moths as a Case Study. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 2113–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzén, M.; Forsman, A.; Karimi, B. Anthropogenic Influence on Moth Populations: A Comparative Study in Southern Sweden. Insects 2023, 14, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settele, J.; Kudrna, O.; Harpke, A.; Kühn, I.; Van Swaay, C.; Verovnik, R.; Warren, M.; Wiemers, M.; Hanspach, J.; Hickler, T.; et al. Climatic Risk Atlas of European Butterflies. BioRisk 2008, 1, 1–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrna, O. Distribution Atlas of Butterflies in Europe; Ges. für Schmetterlingsschutz: Halle, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rákosy, L. Die Noctuiden Rumäniens; Land Oberösterreich, OÖ Landesmuseum: Linz, Austria, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Turčáni, M.; Patočka, J.; Kulfan, J. Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Diószeghy 1935), and Survey Its Presence and Abundance (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae; Hadeninae). J. For. Sci. 2010, 56, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.S.; Shifley, S.R.; Rogers, R.; Dey, D.C.; Kabrick, J.M. The Ecology and Silviculture of Oaks; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mölder, A.; Meyer, P.; Nagel, R.-V. Integrative Management to Sustain Biodiversity and Ecological Continuity in Central European Temperate Oak (Quercus robur, Q. petraea) Forests: An Overview. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 437, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, P.; Roy, A.; Karnatak, H. Assessing the Vulnerability of Oak (Quercus) Forest Ecosystems under Projected Climate and Land Use Land Cover Changes in Western Himalaya. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2275–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzecz, I.; Tkaczyk, M.; Oszako, T. Current Problems of Forest Protection (25–27 October 2022, Katowice Poland). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubenova, A.; Baranowska, M.; Menkis, A.; Davydenko, K.; Nowakowska, J.; Borowik, P.; Oszako, T. Prospects for Oak Cultivation in Europe Under Changing Environmental Conditions and Increasing Pressure from Harmful Organisms. Forests 2024, 15, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diószeghy, L. Einige Neue Varietäten Un Aberrationen von Schmetterlingen Und Ene Neue Noctuide Aus Der Umgebung von Ineu (Borosjeno), Jud. Arad, Rumänien. Verhandlungen und Mitteilungen des Siebenbürgischen Vereins für Naturwissenschaften zu Hermannstadt 1935, 83–84, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- GBIF.org. GBIF Occurrence Download, 2025, 11444. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/DL.GBS4EV (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Issekutz, L. Monima schmidtii Diósz. Ann. Hist. Nat. Musei Natl. Hung. 1955, 47, 323–325. [Google Scholar]

- Căpușe, I. Les Especes Du Genre Orthosia En Roumanie. Trav. Mus. Hist. Nat. Gr. Antipa 1965, 5, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rákosy, L. Lista Sistematică a Noctuidelor Din România Systematische Liste Der Noktuiden Rumäniens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Soc. Lepid. Rom. Bull. Inf. Suppl. 1991, 1, 43–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L. Neue Angaben Über Das Vorkommen Einiger Makrolepidopteren in Ungarn. Folia Entomol. Hung. 1951, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L. A Magyarországi Nagylepkék És Elterjedésük. Folia Entomol. Hung. 1953, 6, 77–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L. A Magyarországi Nagylepkék És Elterjedésük II. Folia Entomol. Hung. 1956, 9, 89–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hreblay, M. New Taxa of the Genus Orthosia Ochsenheimer, 1816 SL. 2. Lepidoptera, Noctuidae. Acta Zool. Hung. 1993, 39, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, K.L.; Rota, J.; Zahiri, R.; Zilli, A.; Wahlberg, N.; Schmidt, B.C.; Lafontaine, J.D.; Goldstein, P.Z.; Wagner, D.L. Toward a Stable Global Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) Taxonomy. Insect Syst. Divers. 2021, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkay, L.; Hreblay, M.; Yela, J.L. Noctuidae Europaeae: Hadeninae II; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beshkov, S. An Identification Guide for NATURA 2000 Species in Bulgaria. 1. Lepidoptera (Butterflies and Moths); Directorate of Vitosha Nature Park: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2011.

- Izeltlabuak.hu Observers. Izeltlabuak.hu Observations Validated to Species Level. 2025. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/RSMDU9 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Beshkov, S. A Contribution to the Knowledge of the Bulgarian Lepidoptera Fauna (Lepidoptera: Macrolepidoptera). Phegea 1995, 23, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- König, F. Die Jugendstände von Orthosia (=Monima = Taeniocampa) schmidtii Dioszeghy (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Entomol. Berichte 1971, 4, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fajčík, J. Die Schmetterlinge Mitteleuropas; J. Fajčík: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, J. The Noctuids (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) of Central Europe; František Slamka: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Korompai, T. A Ponto-Mediterranian Speciality of Europe, the “Hungarian Quaker”, Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Diószeghy 1935) (Formerly Orthosia schmidtii) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). 3rd Eur. Moth Nights 2006, 27, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bekchiev, R.; Beshkov, S.; Arangelov, S.; Kirov, D. Opredelitel Na Zhivotinskite Vidove Za Otsenka Na Gori s Visoka Konservatsionna Stoynost [In Bulgarian]; WWF Bulgaria: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M.E.; Holleman, L.J.M. Warmer Springs Disrupt the Synchrony of Oak and Winter Moth Phenology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dis, N.E.; Sieperda, G.-J.; Bansal, V.; Van Lith, B.; Wertheim, B.; Visser, M.E. Phenological Mismatch Affects Individual Fitness and Population Growth in the Winter Moth. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 290, 20230414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korompai, T.; Kozma, P. A Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Dioszeghy, 1935) Újabb Adatai Észak-Magyarországról (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Folia Hist.-Nat. Musei Matra. 2004, 28, 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Korompai, T. A Vágásos Üzemmódú Erdőgazdálkodás Hatása a Magyar Tavaszi-Fésűsbagolyra (Dioszeghyana Schmidtii). In Az Erdőgazdálkodás Hatása az Erdők Biológiai Sokféleségére Tanulmánygyűjtemény; Márton, K., Ed.; Duna–Ipoly Nemzeti Park Igazgatóság: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; pp. 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Tsikas, A. A New Host Plant Record for Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Dioszeghy, 1935) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from Greece: Implications for Larval Ecology and Conservation. Hist. Nat. Bulg. 2025, 47, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.A.; Mazier, F.; Davison, C.W.; Baines, O.; Czyżewski, S.; Fyfe, R.; Bińka, K.; Boreham, S.; De Beaulieu, J.-L.; Gao, C.; et al. Beyond the Closed-Forest Paradigm: Cross-Scale Vegetation Structure in Temperate Europe before the Late-Quaternary Megafauna Extinctions. Earth Hist. Biodivers. 2025, 3, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oravec, P.; Wittlinger, L.; Máliš, F. Endangered Forest Communities in Central Europe: Mapping Current and Potential Distributions of Euro-Siberian Steppic Woods with Quercus spp. in South Slovak Basin. Biology 2023, 12, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korompai, T.; Péter, K.; Tóth, J.P. A Magyar Tavaszi-Fésűsbagolylepke Dioszeghyana Schmidtii (Diószeghy, 1935) 2006. Évi Monitoring Vizsgálata a Bükki Nemzeti Park Igazgatóságához Tartozó Natura 2000 Területeken. Kutatâsi Jelentés; Kôrnyezetvédelmi és Vizügyi Minisztérium Természetvédelmi Hivatal: Budapest, Hungary, 2006.

- Varga, Z.; Ronkay, L.; Balint, Z.; Laszl, P.M.; Peregovits, L. Checklist of the Fauna of Hungary; Macrolepidoptera; Hungarian Natural History Museum: Budapest, Hungary, 2005; Volume 3.

- Németh, L. A Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Diószeghy, 1935) Újabb Hazai Adata. Folia Entomol. Hung. 1995, 56, 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, Á.; Korompai, T.; Kozma, P.; Katona, G.; Tóth, J.P.; Varga, Z. Természetvédelmi Szempontból Jelentős Lepkefajok És Fajegyüttesek a Mátra Xerotherm Tölgyeseiben (Insecta: Lepidoptera). Termvéd. Közlemények 2012, 18, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, I. A Bükk Hegység Lepkefaunájának Kritikai Vizsgálata 2. Folia Entomol. Hung. 1967, 20, 521–588. [Google Scholar]

- Gyulai, P.; Uherkovich, Á.; Varga, Z. Ujabb Adatok a Magyarországi Nagylepkék Elterjedéséhez (Lepidoptera). Folia Entomol. Hung. 1974, 27, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gyulai, I.; Gyulai, P.; Uherkovich, Á.; Varga, Z. Újabb Adatok a Magyarországi Nagylepkék Elterjedéséhez II. (Lepidoptera). Folia Entomol. Hung. 1979, 32, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, Á.; Korompai, T.; Kozma, P. Új És Ritka Fajok Adatai a Mátra Lepkefaunájának Ismeretéhez II. (Lepidoptera: Macrolepidoptera). Folia Hist.-Nat. Musei Matra. 2010, 34, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Vitkó, T.; Finitha, G. Arló Nagyközség Macroheterocera-Faunájának Vizsgálata (Lepidoptera). Állattani Közlemények 2021, 106, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P. A Deseda-Tó Környékének Éjjeli Nagylepke Faunája. Kaposvári Rippl-Rónai Múz. Közleményei 2020, 7, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P. Contribution to the Butterfly and Moth Fauna of Somogy County (Lepidoptera: Macrolepidoptera). Nat. Somogyiensis 2024, 42, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janák, M.; Černecký, J.; Saxa, A. Monitoring of Animal Species of Community Interest in the Slovak Republic, Results and Assessment in the Period of 2013–2015; State Nature Conservancy of the Slovak Republic: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2015.

- Geryak, Y. The Noctuoidea (Insecta, Lepidoptera) of the Transcarpathian region. Sci. Bull. Uzhhorod Univ. Ser. Biol. 2010, 29, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Geryak, Y.M.; Khalaim, Y.V.; Suchkov, S.I.; Zhakov, O.V.; Bachynskyi, A.I.; Bezuglyi, S.K.; Bidychak, R.M.; Galkin, O.O.; Gera, A.A.; Kavurka, V.V.; et al. Contribution to Knowledge on the Taxonomic Composition and Distribution of Noctuid Moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuoidae) of Ukraine. Ukr. Entomol. J. 2022, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enghiș, E.; Iacob, A.; Kovács, S.; Kovács, Z. The First Records of Pammene querceti (Gozmány, 1957) from Romania and of Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Diószeghy, 1935) from Satu Mare County (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae, Noctuidae). Entomol. Romanica 2025, 29, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitar, C.; Mărcuș, B.; Manci, C.O.; Olteanu, V.; Enghiș, E.; Dumbravă, A.; Sitar, G.M. New Contributions to the Knowledge of the Lepidoptera Fauna of Romania: First Record of Athetis hospes (Freyer, 1831), New Distribution Data for Dioszeghyana schmidtii Diószeghy, 1935 and Polymixis flavicincta (Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775). Entomol. Romanica 2025, 29, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshkov, S.V. An Annotated Systematic and Synonymic Checklist of the Noctuidae of Bulgaria:(Insecta, Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Neue Ent. Nachr. 2000, 49, 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Beshkov, S.; Nahirnić, A. Contribution to Knowledge of the Balkan Lepidoptera (Lepidoptera: Macrolepidoptera). Ecol. Montenegrina 2020, 30, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshkov, S.; Langourov, M. Butterflies and Moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera) of the Bulgarian Part of Eastern Rhodopes. Biodivers. Bulg. 2004, 2, 525–676. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović, D.V.; Ćurčić, S.B.; Ćurčić, B.P.M.; Makarov, S.E. The Application of IUCN Red List Criteria to Assess the Conservation Status of Moths at the Regional Level: A Case of Provisional Red List of Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) in Serbia. J. Insect Conserv. 2013, 17, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuric, M.; Brosens, D. Arthropod Observations Derived from HabiProt Alciphron Database in Serbia. 2025. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/dataset/d92e92e0-8d20-4756-a60b-3746f408c14c (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Vasić, K. Fauna Sovica (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Srbije; Zbornik radova o fauni Srbije; SANU—Odeljenje Hemijskih i Bioloških Nauka: Beograd, Serbia, 2002; Volume 6, pp. 165–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, H. Die Noctuidae Griechenlands (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae)–Herbipoliana; Dr. Ulf Eitschberger: Marktleuthen, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbauer, F.; Theimer, F. Eriogaster inspersa Staudinger, 1879: New for the Fauna of Europe (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). Nachrichten Entomol. Ver. Apollo 2016, 37, 159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Koçak, A.Ö.; Kemal, M. Revised Checklist of the Lepidoptera of Türkiye; Priamus Serial Publication of the Centre for Entomological Studies: Ankara, Türkiye, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tarauş, G.; Okyar, Z. Records of 20 New Moth (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera) Species for Turkish Thrace. Trak. Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2016, 17, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Szentirmai, I.; Mesterházy, A.; Varga, I.; Schubert, Z.; Sándor, L.C.; Ábrahám, L.; Kőrösi, Á. Habitat Use and Population Biology of the Danube Clouded Yellow Butterfly Colias myrmidone (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) in Romania. J. Insect Conserv. 2014, 18, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteleev, P. The Rodents of the Palaearctic: Composition and Areas; Institute of Problems of Ecology and Evolution, RAS: Moscow, Russia, 1998.

- Magyar Közlöny, 158. Szám, 66/2015 (X. 26) FM Rendelet. 2015. Available online: https://magyarkozlony.hu/dokumentumok/38dfbfbadaeef62f3a67ab5443bac25c1645933e/megtekintes (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Pastorális, G.; Buschmann, F.; Ronkay, L. Magyarország Lepkéinek Névjegyzéke=Checklist of the Hungarian Lepidoptera. E-Acta Nat. Pannonica 2016, 12, 1–258. [Google Scholar]

- Rákosy, L.; Corduneanu, C.; Crișan, A.; Goia, M.; Groza, B.; Kovács, S. Lista Rosie a Fluturilor Din Romania; Presa Universitara Clujeana: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Ordinance no. 57 of 20 June 2007 of the Regime of Protected Natural Areas, Conservation of Natural Habitats, Wild Flora and Fauna. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/rom197166.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Zakon Za Biologichnoto Raznoobrazie (Biological Diversity Act), Promulgated SG No. 77/2002, Amended SG No. 88/2023 (Bulgaria). 2023. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/legislation/details/20078 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Jakšić, P. About the Need to Publish a New Red Data Book of Serbian Butterflies and Moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera). Zastita Prir. 2019, 69, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council. The EU Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora). 1992. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eur34772.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Revised Annex, I. Of Resolution 6 (1998) of the Standing Committee to the Bern Convention. 2011. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680746347 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Hegedüšová, K.; Žarnovičan, H.; Kanka, R.; Šuvada, R.; Kollár, J.; Galvánek, D.; Roleček, J. Thermophilous Oak Forests in Slovakia: Vegetation Classification and an Expert System. Preslia 2021, 93, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrík, M.; Bažány, M.; Čiliak, M.; Knopp, V.; Máliš, F.; Ujházyová, M.; Vaško, Ľ.; Vladovič, J.; Ujházy, K. Half a Century of Herb Layer Changes in Quercus-Dominated Forests of the Western Carpathians. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 544, 121151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csölleová, L.; Kotrík, M.; Kupček, D.; Knopp, V.; Máliš, F. Post-Harvest Recovery of Microclimate Buffering and Associated Temporary Xerophilization of Vegetation in Sub-Continental Oak Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 572, 122238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M.; Elia, A.; Oton, G.; Piccardo, M.; Ceccherini, G.; Forzieri, G.; Migliavacca, M.; Cescatti, A.; Girardello, M. Enhanced Structural Diversity Increases European Forest Resilience and Potentially Compensates for Climate-Driven Declines. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimková, M.; Vacek, S.; Šimůnek, V.; Vacek, Z.; Cukor, J.; Hájek, V.; Bílek, L.; Prokůpková, A.; Štefančík, I.; Sitková, Z.; et al. Turkey Oak (Quercus cerris L.) Resilience to Climate Change: Insights from Coppice Forests in Southern and Central Europe. Forests 2023, 14, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozel, P.; Sebek, P.; Platek, M.; Benes, J.; Zapletal, M.; Dvorsky, M.; Lanta, V.; Dolezal, J.; Bace, R.; Zbuzek, B.; et al. Connectivity and Succession of Open Structures as a Key to Sustaining Light-demanding Biodiversity in Deciduous Forests. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 2951–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.S.; Maes, D.; Van Swaay, C.A.M.; Goffart, P.; Van Dyck, H.; Bourn, N.A.D.; Wynhoff, I.; Hoare, D.; Ellis, S. The Decline of Butterflies in Europe: Problems, Significance, and Possible Solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2002551117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percel, G.; Cizek, L.; Benes, J.; Miklin, J.; Vrba, P.; Sebek, P. Nature Conservation and Insect Decline in Central Europe: Loss of Lepidoptera in Key Protected Sites Is Accompanied by Substantial Land Cover Changes. Eur. J. Entomol. 2025, 122, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapletal, M.; Zapletalova, L.; Bartonova, A.S.; Slancarova, J.L.; Konvicka, M. Hyperdiverse Insect Group Indicates Forest Encroachment a Threat to the Mediterranean Biodiversity Hot-Spot. Biol. Conserv. 2026, 313, 111529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asch, M.; Visser, M.E. Phenology of Forest Caterpillars and Their Host Trees: The Importance of Synchrony. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, J.J.; Meehan, T.D.; Lindroth, R.L. Atmospheric Change Alters Foliar Quality of Host Trees and Performance of Two Outbreak Insect Species. Oecologia 2012, 168, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Halder, I.; Barbaro, L.; Jactel, H. Conserving Butterflies in Fragmented Plantation Forests: Are Edge and Interior Habitats Equally Important? J. Insect Conserv. 2011, 15, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, J. Butterflies Benefit from Forest Edge Improvements in Western European Lowland Forests, Irrespective of Adjacent Meadows’ Use Intensity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 521, 120413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.A.; Telfer, M.G.; Roy, D.B.; Preston, C.D.; Greenwood, J.J.D.; Asher, J.; Fox, R.; Clarke, R.T.; Lawton, J.H. Comparative Losses of British Butterflies, Birds, and Plants and the Global Extinction Crisis. Science 2004, 303, 1879–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.J.A.; New, T.R.; Lewis, O.T. (Eds.) Insect Conservation Biology; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kingdom Animalia |

| Phylum Arthropoda |

| Subphylum Hexapoda |

| Class Insecta |

| Order Lepidoptera |

| Superfamily Noctuoidea |

| Family Noctuidae |

| Subfamily Noctuinae |

| Tribe Orthosiini |

| Genus Dioszeghyana Hreblay, 1993 |

| Species Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Dioszeghy, 1935) |

| Habitat Area Code | Type of Habitat |

|---|---|

| 2180 | Wooded dunes of the Atlantic, Continental, and Boreal regions |

| 91AA | Eastern white oak woods |

| 91F0 | Riparian mixed forests of Quercus robur, Ulmus laevis, and Ulmus minor, Fraxinus excelsior or Fraxinus angustifolia, typically found along great rivers |

| 91G0 | Pannonic woods with both Quercus petraea and Carpinus betulus |

| 91H0 | Pannonian woods with Quercus pubescens |

| 91I0 | Euro-Siberian steppic woods with Quercus spp. |

| 91L0 | Illyrian oak–hornbeam forests (Erythronio-Carpinion) |

| 91M0 | Pannonian–Balkanic turkey oak—sessile oak forests |

| Country | Protected Area | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | Bozhite mostove | BG0000487 |

| Derventski vazvishenia 2 | BG0000219 | |

| Emine–Irakli | BG0001004 | |

| Kamchia | BG0000116 | |

| Lomovete | BG0000608 | |

| Popintsi | BG0001039 | |

| Rabrovo | BG0000339 | |

| Rodopi-Iztochni | BG0001032 | |

| Rodopi-Sredni | BG0001031 | |

| Ropotamo | BG0001001 | |

| Sakar | BG0000212 | |

| Tsar Petrovo | BG0000340 | |

| Vidbol | BG0000498 | |

| Voynitsa | BG0000500 | |

| Vrachanski Balkan | BG0000166 | |

| Zhdreloto na reka Tundzha | BG0000217 | |

| Greece | Vouna Evrou | GR1110005 |

| Hungary | Aggteleki-karszt és peremterületei | HUAN20001 |

| Bélmegyeri Fás-puszta | HUKM20013 | |

| Bézma | HUBN20057 | |

| Börzsöny | HUDI20008 | |

| Budai-hegység | HUDI20009 | |

| Budaörsi kopárok | HUDI20010 | |

| Bujáki Csirke-hegy és Kántor-rét | HUBN20058 | |

| Bujáki Hényeli-erdő és Alsó-rét | HUBN21094 | |

| Domaházai Hangony-patak völgye | HUBN20021 | |

| Egerbakta-Bátor környéki erdők | HUBN20012 | |

| Észak-zselici erdőségek | HUDD20016 | |

| Északi-Gerecse | HUDI20018 | |

| Gerecse | HUDI20020 | |

| Gödöllői-dombság | HUDI20023 | |

| Gyepes-völgy | HUBN20014 | |

| Gyöngyöspatai Havas | HUBN20050 | |

| Gyöngyöstarjáni Világos-hegy és Rossz-rétek | HUBN20048 | |

| Hencidai Csere-erdő | HUHN20011 | |

| Hevesaranyosi-fedémesi dombvidék | HUBN20013 | |

| Hór-völgy, Déli-Bükk | HUBN20002 | |

| Hortobágy | HUHN20002 | |

| Izra-völgy és az Arlói-tó | HUBN20015 | |

| Kerecsendi Berek-erdő és Lógó-part | HUBN20038 | |

| Kisgyőri Ásottfa-tető-Csókás-völgy | HUBN20005 | |

| Kisgyőri Halom-vár-Csincse-völgy-Cseh-völgy | HUBN20007 | |

| Kismarja-Pocsaj-Esztári-gyepek | HUHN20008 | |

| Körösközi erdők | HUHN20008 | |

| Közép-Bihar | HUHN20013 | |

| Mátrabérc-fallóskúti-rétek | HUBN20049 | |

| Nagybarcai Liget-hegy és sajóvelezdi Égett-hegy | HUBN20025 | |

| Nagylóci Kő-hegy | HUBN21095 | |

| Nyugat-Cserhát és Naszály | HUDI20038 | |

| Nyugat-Mátra | HUBN20051 | |

| Pilis és Visegrádi-hegység | HUDI20039 | |

| Salgó | HUBN20064 | |

| Szarvaskő | HUBN20004 | |

| Szentai-erdő | HUDD20063 | |

| Szentkúti Meszes-tető | HUBN20055 | |

| Szomolyai Kaptár-rét | HUBN20010 | |

| Tard környéki erdőssztyepp | HUBN20009 | |

| Tepke | HUBN20056 | |

| Upponyi-szoros | HUBN20018 | |

| Vár-hegy-Nagy-Eged | HUBN20008 | |

| Velencei-hegység | HUDI20053 | |

| Vértes | HUDI30001 | |

| Romania | Betfia | ROSAC0008 |

| Câmpia Nirului-Valea Ierului | ROSPA0016 | |

| Dealul Mocrei-Rovina–Ineu | ROSAC0218 | |

| Lunca Barcăului | ROSPA0067 | |

| Lunca Mureșului Inferior | ROSAC0108 | |

| Parcul Natural Cefa | ROSCI0025 | |

| Slovakia | Burdov | SKUEV0184 |

| Čajkovské bralie | SKUEV0262 | |

| Cerovina | SKUEV0129 | |

| Mochovská cerina | SKUEV0867 | |

| Patianska cerina | SKUEV0882 | |

| Rataj | SKUEV0865 | |

| Starý vrch | SKUEV0157 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tsikas, A. Ecology, Distribution, and Conservation Considerations of the Oak-Associated Moth Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Diversity 2026, 18, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020072

Tsikas A. Ecology, Distribution, and Conservation Considerations of the Oak-Associated Moth Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Diversity. 2026; 18(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsikas, Angelos. 2026. "Ecology, Distribution, and Conservation Considerations of the Oak-Associated Moth Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)" Diversity 18, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020072

APA StyleTsikas, A. (2026). Ecology, Distribution, and Conservation Considerations of the Oak-Associated Moth Dioszeghyana schmidtii (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Diversity, 18(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020072