Zooplankton Indicators of Ecological Functioning Along an Urbanisation Gradient

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

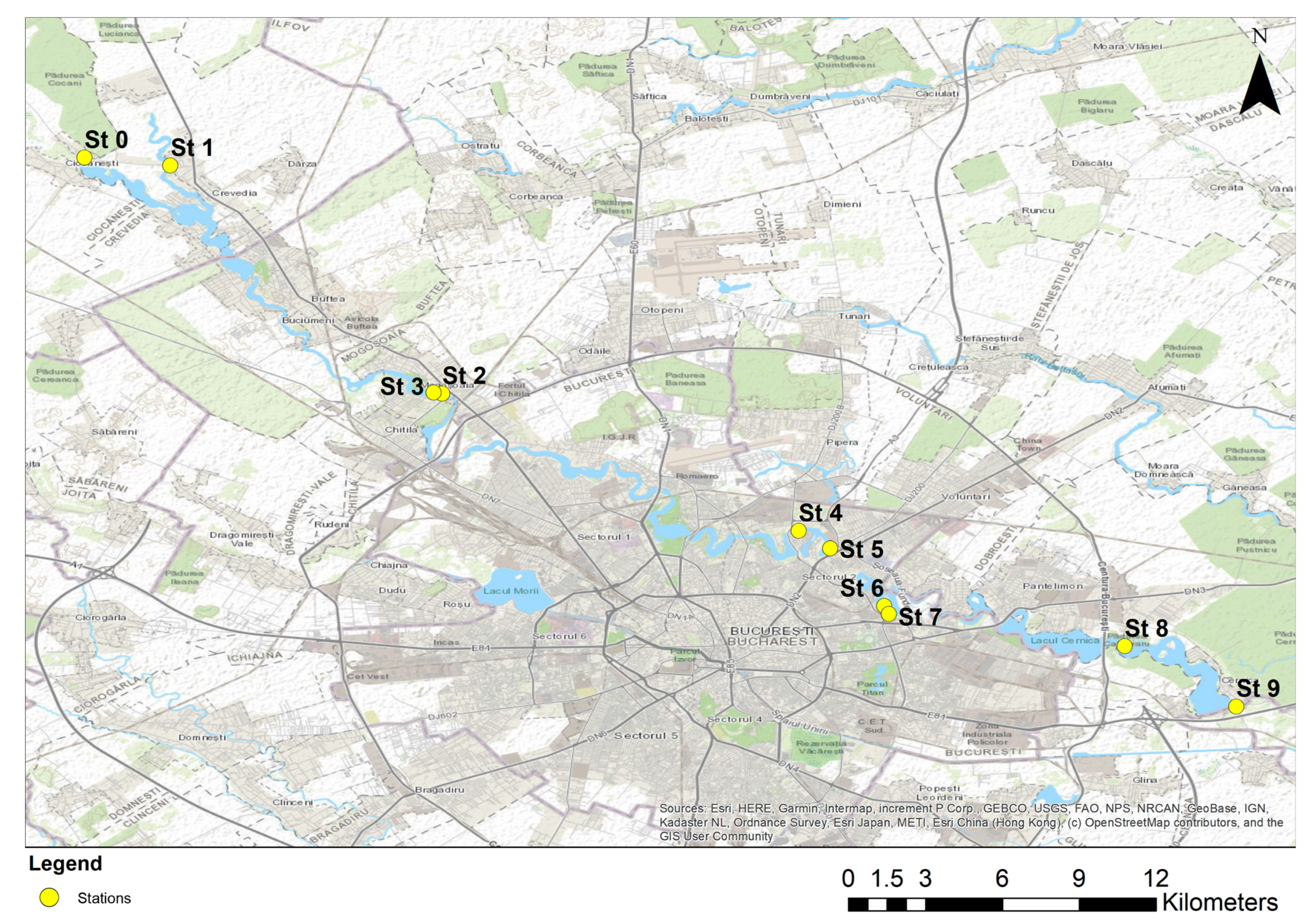

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Sites

- Station 0 (Cernica river natural sector)—rural area with natural characteristics, low anthropogenic influences;

- Station 1 (Crevedia)—rural area with natural features, low anthropogenic influences;

- Stations 2 and 3 (Mogoșoaia Lake)—peri-urban area with modified course in the lake, with mixed influences;

- Stations 4 and 5 (Plumbuita Lake)—urban area, strongly influenced by human activity;

- Stations 6 and 7 (Fundeni Lake)—urban area, strongly influenced by human activity;

- Station 8 (Cernica Lake)—peri-urban area, with cumulative influences;

- Station 9 (Cernica Natural Channel)—rural area, low anthropogenic influences.

2.2. Environmental Parameters

2.3. Zooplankton Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Trophic State Indices

2.4.1. Rotifera Trophic Index

2.4.2. Crustacea Trophic Index

2.4.3. Carlson’s Trophic State Index (CTSI)

2.5. Resource Use Efficiency (RUE)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Conditions

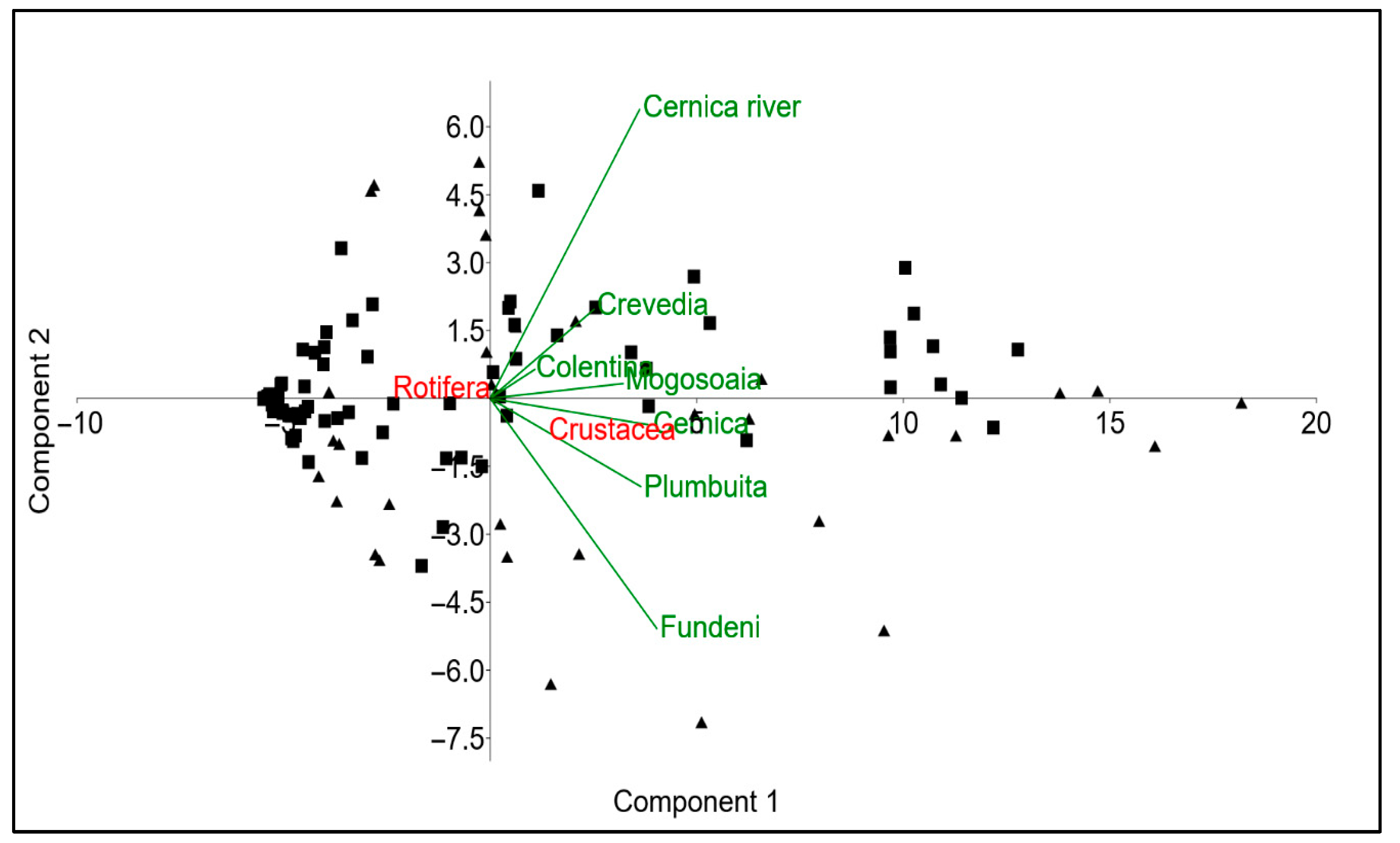

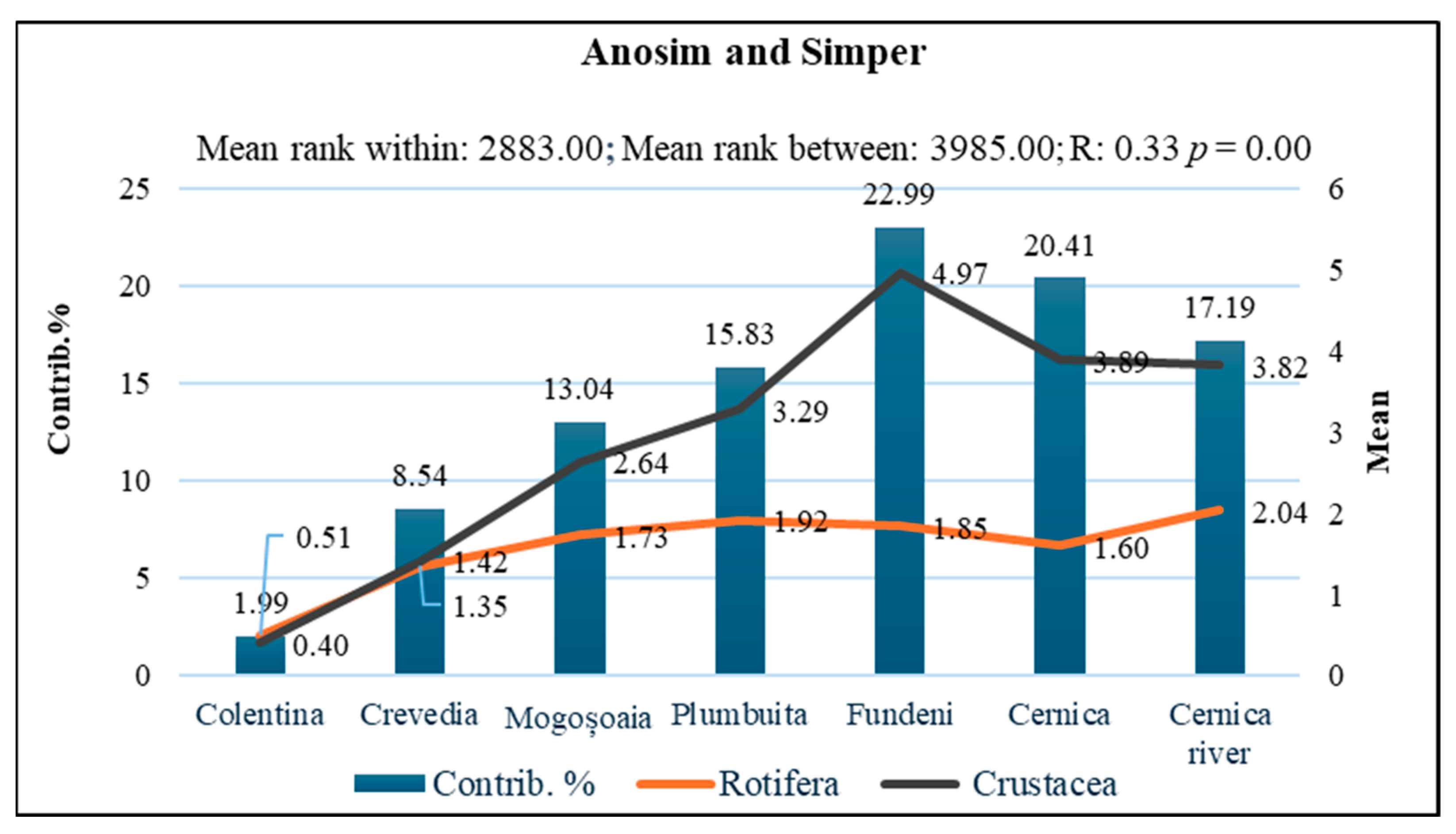

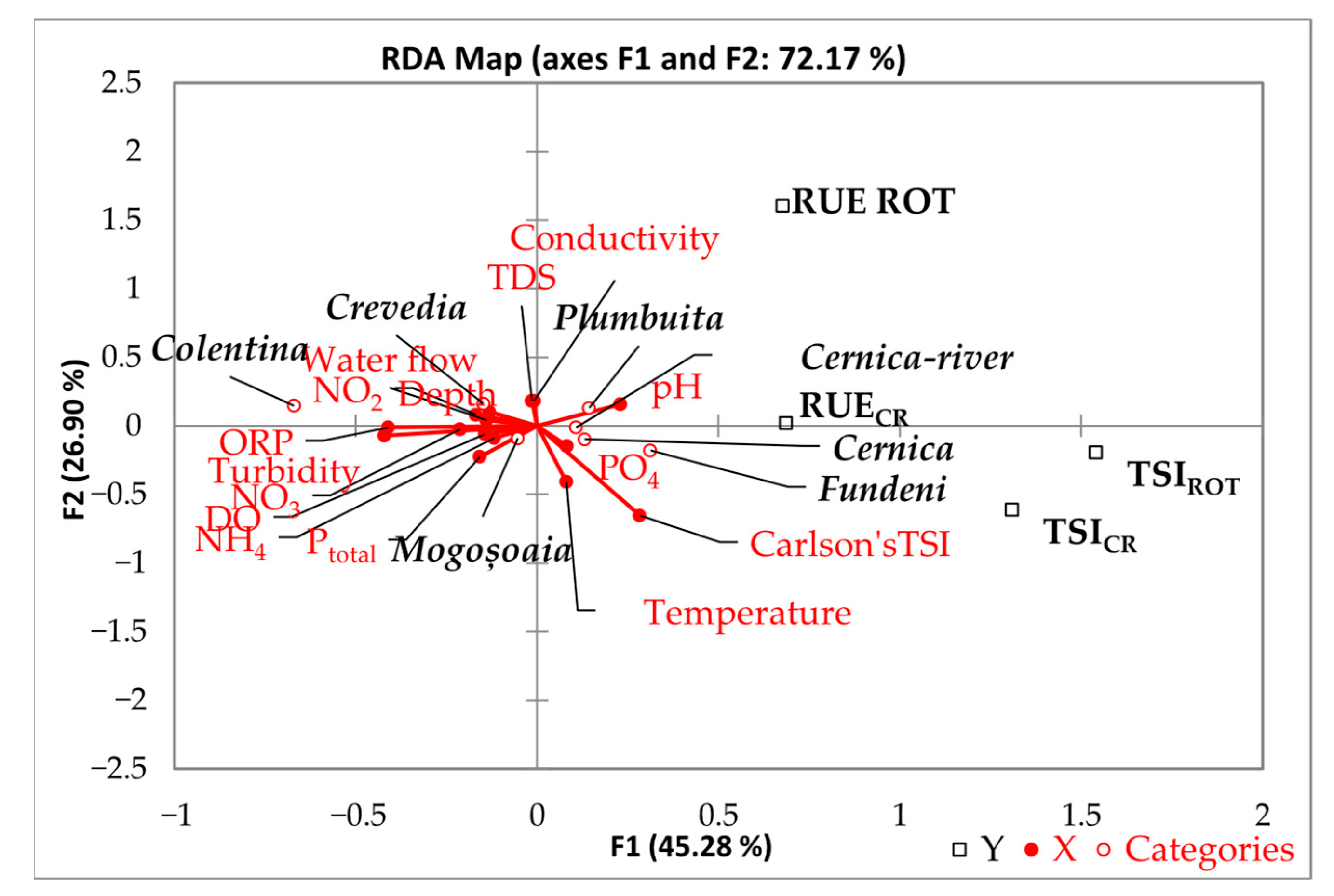

3.2. Indicator Species and Habitat-Specific Patterns in Zooplankton Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Villalba Duré, G.A.; Simões, N.R.; Magalhães Braghin, L.S.; Ribeiro, S.M.M.S. Effect of eutrophication on the functional diversity of zooplankton in shallow ponds in Northeast Brazil. J. Plankton Res. 2021, 43, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Qin, G.; Yu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; An, S.; Liu, R.; Leng, X.; Wan, Y. Urbanization has changed the distribution pattern of zooplankton species diversity and the structure of functional groups. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Feng, K.; Du, X.; Yuan, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Z. Effects of land use and environmental gradients on the taxonomic and functional diversity of rotifer assemblages in lakes along the Yangtze River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S.; Marques, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. The role of zooplankton in estuarine ecosystem functioning and resilience. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 165, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodapp, D.; Hillebrand, H.; Striebel, M. Unifying the concept of resource use efficiency in ecology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavan, E.L.; Henson, S.A.; Belcher, A.; Sanders, R. Role of Zooplankton in Determining the Efficiency of the Biological Carbon Pump. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Nõges, P.; Davidson, T.A.; Haberman, J.; Nõges, T.; Blank, K.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Søndergaard, M. Zooplankton as indicators in lakes: A science-based plea for including zooplankton in the ecological quality assessment of lakes according to the European Water Framework Directive (WFD). Hydrobiologia 2011, 676, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont-Karabin, J. The usefulness of zooplankton as indicators of lake ecosystem health: The Rotifer trophic state index. Pol. J. Ecol. 2012, 60, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ejsmont-Karabin, J.; Karabin, A. The suitability of crustacean zooplankton as lake ecosystem indicators: Crustacean trophic state index. Pol. J. Ecol. 2013, 61, 561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, S.I.; Arnott, S.E.; Cottingham, K.L. The relationship in lake communities between primary productivity and species richness. Ecology 2000, 81, 2662–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabin, A. Ecological characteristics of lakes in northeastern Poland versus their trophic gradient. X. Variability of crustacean zooplankton indices used in lake classification. Ekol. Pol. 1985, 33, 567–590. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Xu, S.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Lin, Q.; Han, B.-P. Urbanization Increases Biotic Homogenization of Zooplankton Communities in Tropical Reservoirs. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.R.; Chen, G.; MacDonald, G.K.; Vermaire, J.C.; Bennett, E.M.; Gregory-Eaves, I. Phosphorus and land-use changes are significant drivers of cladoceran community composition and diversity: An analysis over spatial and temporal scales. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 67, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sládeček, V. Rotifers as indicators of water quality. Hydrobiologia 1983, 100, 169–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpowicz, M.; Kuczyńska-Kippen, N.; Sługocki, Ł.; Czerniawski, R.; Bogacka-Kapusta, E.; Ejsmont-Karabin, J. Zooplankton as indicators of lake trophic status: Novel universal metrics from 224 temperate lakes. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, J.; Lu, A.; Zhu, P.; Yin, X. Effects of phytoplankton diversity on resource use efficiency in a eutrophic urban river of Northern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1389220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L.; Miao, M.; Huang, H. Biodiversity effects on resource use efficiency and community turnover of plankton in Lake Nansihu, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 11279–11288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.J.; Beisner, B.E. Zooplankton biodiversity and lake trophic state: Explanations invoking resource abundance and distribution. Ecology 2007, 88, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchman, E.; Ohman, M.D.; Kiørboe, T. Trait-Based Approaches to Zooplankton Communities. J. Plankton Res. 2013, 35, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, L.; Ioana-Toroimac, G.; Cocoș, O.; Ghiță, F.A.; Mailat, E. Urbanization effects on the river systems in the Bucharest City Region (Romania). Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2016, 2, e01247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, M.; Stoiculescu, R.C. Landscape changes in Colentina River Basin (between Buftea and the confluence with Dâmbovița) as reflected in cartographic documents (1791–2000). Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 4, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Iojă, C.; Onose, D.; Cucu, A.; Ghervase, L. Changes in water quality in the lakes along Colentina River under the influence of the residential areas in Bucharest. Sel. Top. Energy Environ. Sustain. Dev. Landscaping 2010, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, P.; Radu, V.M.; Diacu, E.; Marcu, E. Assessment of water quality in the lakes along Colentina River. In Advanced Engineering Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Bäch, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 13, pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Krom, M.D. Spectrophotometric determination of ammonia: A study of a modified Berthelot reaction using salicylate and dichloroisocyanurate. Analyst 1980, 105, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartari, G.; Mosello, R. Metodologie analitiche e controlli di qualità nel laboratorio chimico dell’Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia. In Documenta Dell’Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia; Verbania Pallanza: Verbania, Italy, 1997; Volume 60, pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rudescu, L. Rotatoria. The Fauna of Romania. Trochelminthes; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1960. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Negrea, Ş. Cladocera. In Romanian Fauna; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1983. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Damian-Georgescu, A. Romanian Fauna. Crustacea; Copepoda. Cyclopidae; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1963; Volume IV. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Damian-Georgescu, A. Romanian Fauna. Crustacea; Copepoda. Calanoida; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1966; Volume IV. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, E. The estimation of abundance and biomass of zooplankton in samples. In A Manual on Methods for the Assessment of Secondary Productivity in Freshwaters, 2nd ed.; Downing, J.A., Rigler, F.H., Eds.; Blackwell Scientific: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 228–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ruttner-Kolisko, A. Suggestions for biomass calculation of plankton rotifers. Arch. Hydrobiol. Beih. Ergebn Limnol. 1977, 8, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bottrell, H.H.; Duncan, A.; Gliwicz, Z.M.; Grygierek, E.; Herzig, A.; Hillbricht-Ilkowska, A.; Kurasawa, H.; Larsson, P.; Weglenska, T. A review of some problems in zooplankton production studies. North-West. J. Zool. 1976, 24, 419–456. [Google Scholar]

- Ejsmont-Karabin, J. Empirical equations for biomass calculation of planktonic rotifers. Pol. Arch. Hydrobiol. 1998, 45, 513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, H.J.; van de Velde, I.; Dumont, S. The dry weight estimate of biomass in a selection of Cladocera, Copepoda and Rotifera from the plankton, periphyton, and benthos of continental waters. Oecologia 1975, 19, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.E. A trophic state index for lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filstrup, C.T.; Hillebrand, H.; Heathcote, A.J.; Harpole, W.S.; Downing, J.A. Cyanobacteria dominance influences resource use efficiency and community turnover in phytoplankton and zooplankton communities. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janžekovič, F.; Novak, T. Analyze Ecological Niches. In Principal Component Analysis: Multidisciplinary Applications; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; p. 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T. Paleontological Data Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology, 3rd English ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Addinsoft. XLSTAT-Pro: Data Analysis and Statistical Solution for Microsoft Excel; Addinsoft: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, V.; Rollwagen-Bollens, G.; Bollens, S.M.; Zimmerman, J. Effects of Grazing and Nutrients on Phytoplankton Blooms and Microplankton Assemblage Structure in Four Temperate Lakes Spanning a Eutrophication Gradient. Water 2021, 13, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.L.; Pollard, A.I. Changes in the relationship between zooplankton and phytoplankton biomasses across a eutrophication gradient. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018, 63, 2493–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umi, W.A.D.; Yusoff, F.M.; Balia Yusof, Z.N.; Ramli, N.M.; Sinev, A.Y.; Toda, T. Composition, Distribution, and Biodiversity of Zooplanktons in Tropical Lentic Ecosystems with Different Environmental Conditions. Arthropoda 2024, 2, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, I.C.; Green, J.D.; Thomasson, K. Do Rotifers Have Potential as Bioindicators of Lake Trophic State? Verh. Int. Ver. Limnol. 2001, 27, 3497–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, J.E.; Stemberger, R.S. Zooplankton (especially crustaceans and rotifers) as indicators of water quality. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 1978, 97, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.V.; Tockner, K. Biodiversity: Towards a unifying theme for river ecology. Freshw. Biol. 2001, 46, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.D. Landscapes and riverscapes: The influence of land use on stream ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attayde, J.L.; Bozelli, R.L. Assessing the indicator properties of zooplankton assemblages to disturbance gradients by canonical correspondence analysis. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1998, 55, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaneto, D.; De Smet, W.H.; Ricci, C. Rotifers in saltwater environments: Re-evaluation of an inconspicuous taxon. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2006, 86, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, J.; Haldna, M. Indices of zooplankton community as valuable tools in assessing the ecological status of eutrophic lakes: Long-term study of Lake Võrtsjärv. J. Limnol. 2014, 73, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowles, T.J.; Olson, R.J.; Chisholm, S.W. Food Selection by Copepods: Discrimination on the Basis of Food Quality. Mar. Biol. 1988, 100, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosińska, J.; Kowalczewska-Madura, K.; Kozak, A.; Romanowicz-Brzozowska, W.; Gołdyn, R. Were There Any Changes in Zooplankton Communities Due to the Limitation of Restoration Treatments? Limnol. Rev. 2021, 21, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seda, J.; Devetter, M. Zooplankton community structure along a trophic gradient in a canyon-shaped dam reservoir. J. Plankton Res. 2000, 22, 1829–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Escober, E.J.; Espino, M.P. A new trophic state index for assessing eutrophication of Laguna de Bay, Philippines. Environ. Adv. 2023, 13, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opiyo, S.; Getabu, A.M.; Sitoki, L.M.; Shitandi, A.; Ogendi, G.M. Application of the Carlson’s trophic state index for the assessment of trophic status of Lake Simbi ecosystem, a deep alkaline-saline lake in Kenya. Int. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2019, 7, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Malla, R. Carlson’s trophic state index for the assessment of trophic state of Phewa, Begnas and Rupa Lakes in Kaski District, Nepal. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 46, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stanachkova, M.; Dashinov, D.; Traykov, I. Comparison of the zooplankton-based RCC to Carlson’s trophic state indices and water quality parameters. IOP Conference Series, Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publ. 2024, 1305, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-L.; Karangan, A.; Huang, Y.M.; Kang, S.-F. Eutrophication factor analysis using Carlson trophic state index (CTSI) towards non-algal impact reservoirs in Taiwan. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2022, 32, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, S.; Vieira, L.C.G.; Velho, L.F.M.; Bonecker, C.C.; de Carvalho, P.; Bini, L.M. Zooplankton community metrics as indicators of eutrophication in urban lakes. Nat. Conserv. 2011, 9, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, C.D.; Bayne, D.R.; West, M.S. Zooplankton trophic state relationships in four Alabama–Georgia reservoirs. Lake Reserv. Manag. 1995, 11, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkova, I.V.; Kostryukova, A.; Shchelkanova, E.; Trofimenko, V. Zooplankton as indicator of trophic status of lakes in Ilmen State Reserve, Russia. Biodivers. J. Biol. Divers. 2021, 22, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanjare, A.I.; Shinde, Y.S.; Padhye, S. Faunistic overview of the freshwater zooplankton from the urban riverine habitats of Pune, India. J. Threat. Taxa 2023, 15, 23879–23888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Wang, X.; Elser, J.J. Unintended nutrient imbalance induced by wastewater effluent inputs to receiving water and its ecological consequences. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Feng, H.; Witherell, B.B.; Alebus, M.; Mahajan, M.D.; Zhang, W.; Yu, L. Causes, assessment, and treatment of nutrient (N and P) pollution in rivers, estuaries, and coastal waters. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2018, 4, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.R.; Caraco, N.F.; Correll, D.L.; Howarth, R.W.; Sharpley, A.N.; Smith, V.H. Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorus and nitrogen. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.H.; Tilman, G.D.; Nekola, J.C. Eutrophication: Impacts of excess nutrient inputs on freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 1999, 100, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptacnik, R.; Solimini, A.G.; Andersen, T.; Tamminen, T.; Brettum, P.; Lepistö, L.; Willén, E.; Rekolainen, S. Diversity predicts stability and resource use efficiency of phytoplankton communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5134–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhu, M.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhu, G. Spatiotemporal dependency of resource use efficiency on phytoplankton diversity in Lake Taihu. Limnol. Ocean. 2022, 67, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obertegger, U.; Manca, M. Response of rotifer functional groups to changing trophic state and crustacean community. J. Limnol. 2011, 70, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahuquillo, M.; Miracle, M.R. Crustacean and rotifer seasonality in a Mediterranean temporary pond with high biodiversity (Lavajo de Abajo de Sinarcas, Eastern Spain). Limnetica 2010, 29, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liu, G.; Yin, X. Nutrient-Driven Shifts in Zooplankton Structural–Functional Dynamics across Different Types of Freshwater Systems. Water Biol. Secur. 2025, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, D.J.; Post, J.R.; Mills, E.L. Trophic relationships in freshwater pelagic ecosystems. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1986, 43, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarova, N.; Napiórkowski, P. Are rotifer indices suitable for assessing the trophic status in slow-flowing waters of canals? Hydrobiologia 2024, 851, 3013–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, B.; He, L.; Huang, Y.; Guo, X.; Xu, W.; Zhu, C. Tempo-spatial variations of zooplankton communities in relation to environmental factors and the ecological implications: A case study in the hinterland of the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczak, T.; Wojtal-Frankiewicz, A.; Frankiewicz, P.; Kaczkowski, Z.; Oleksińska, Z.; Bednarek, A.; Zalewski, M. Comprehensive approach to restoring urban recreational reservoirs. Part 2—Use of zooplankton as indicators for the ecological quality assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowszys, M.; Dunalska, J.A.; Jaworska, B. Zooplankton response to organic carbon level in lakes of differing trophic states. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2014, 412, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station | Area Type | Coordinates (Lat, Lon) | Ecosystem | % Estimated Urbanisation Degree | Anthropization Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | r | 44°36′22.6″ N, 25°52′36.6″ E | Colentina river | 5–10% | Low |

| S1 | r | 44°26′48.6″ N, 26°02′45.0″ E | Crevedia branch | 10–20% | Low–Medium |

| S2 | pu | 44°31′23.9″ N, 26°00′09.3″ E | Mogoșoaia lake | 30–40% | Medium |

| S3 | pu | 44°31′25.4″ N, 25°59′58.54″ E | Mogoșoaia lake | 30–40% | Medium |

| S4 | u | 44°28′30.4″ N, 26°07′40.0″ E | Plumbuita | 60–70% | High |

| S5 | u | 44°28′08.5″ N, 26°08′19.9″ E | Plumbuita | 70–80% | High |

| S6 | u | 44°26′55.6″ N, 26°09′28.3″ E | Fundeni | 70–85% | High |

| S7 | u | 44°26′45.8″ N, 26°09′34.2″ E | Fundeni | 75–85% | High |

| S8 | pu | 44°26′04.8″ N, 26°14′32.3″ E | Cernica lac | 20–35% | Medium |

| S9 | r | 44°24′48.5″ N, 26°16′53.7″ E | Cernica river | 10–20% | Low–Medium |

| Parameters | Colentina River Sector | Crevedia | Mogoșoaia | Plumbuita | Fundeni | Cernica | Cernica River Sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth (m) | 0.86 | 1.63 | 1.11 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| Transparency (m) | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.38 |

| Turbidity | 38.48 | 18.69 | 17.79 | 18.58 | 19.18 | 19.42 | 21.75 |

| Temperature (°C) | 16.57 | 19.39 | 19.67 | 20.60 | 20.18 | 19.40 | 19.67 |

| pH | 8.07 | 8.59 | 8.70 | 8.68 | 8.62 | 8.60 | 8.57 |

| Water flow (m/s) | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | 497.00 | 463.00 | 442.72 | 482.11 | 512.83 | 535.78 | 523.22 |

| DO (mg O2L−1) | 15.92 | 6.86 | 7.57 | 6.98 | 12.87 | 9.40 | 9.31 |

| ORP | 28.05 | 8.05 | −2.01 | −20.00 | −24.02 | −19.90 | −16.47 |

| TDS | 248.25 | 243.88 | 221.39 | 241.00 | 256.28 | 267.89 | 261.67 |

| Ptotal (mg P L−1) | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| PO43− (mg L−1) | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| NH4+ (mg L−1) | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| NO2− (mg L−1) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| NO3− (mg L−1) | 3.81 | 2.85 | 2.27 | 1.93 | 2.79 | 3.34 | 2.75 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotifera | |||||||

| Anuraeopsis fissa Gosse, 1851 | 25.17 | ||||||

| Asplanchna brightwelli Gosse, 1850 | 18.08 | ||||||

| Asplanchna herricki Guerne, 1888 | 19.99 | ||||||

| Asplanchna priodonta Gosse, 1850 | |||||||

| Bdelloidea g.sp. | 30.69 | ||||||

| Brachinus falcatus Zacharias 1898 | 14.39 | 12.91 | |||||

| Brachionus angularis Gosse, 1851 | 27.45 | ||||||

| Brachionus budapestinensis Daday, 1885 | 21.00 | ||||||

| Brachionus calyciflorus Pallas,1766 | 31.59 | ||||||

| Brachionus calyciflorus var. dorcas Ehrenberg, 1838 | 10.85 | ||||||

| Brachionus diversicornis Daday, 1883 | 21.55 | 31.88 | |||||

| Brachionus forficula Wierzejski 1891 | 30.29 | ||||||

| Brachionus plicatilis Müller, 1786 | 29.59 | ||||||

| Brachionus quadridentatus Hermann, 1783 | 16.37 | ||||||

| Cephalodella sp. | 10.22 | ||||||

| Colurella adriatica Ehrenberg, 1831 | 8.55 | ||||||

| Colurella obtusa Gosse, 1886 | 16.67 | ||||||

| Dicranophorus sp. | 7.99 | ||||||

| Filinia longiseta Ehrenberg, 1834 | |||||||

| Hexarthra fenica Levander, 1892 | 22.22 | ||||||

| Keratella cochlearis Gosse, 1851 | 30.11 | ||||||

| Keratella valga Ehrenberg, 1834 | 16.80 | ||||||

| Pompholyx complanata Gosse, 1851 | 46.50 | 19.96 | |||||

| Pompholyx sulcata Hudson, 1885 | 20.27 | ||||||

| Synchaeta oblonga Ehrenberg, 1832 | 16.55 | ||||||

| Synchaeta stylata Wierzejski, 1893 | 8.82 | ||||||

| Trichocerca cylindrica Imhof, 1891 | 19.82 | ||||||

| Trichocerca dixton-nutalli (Jennings, 1903) | 25.78 | ||||||

| Trichocerca pusilla Jennings, 1903 | 42.63 | ||||||

| Trichocerca rattus Müller, 1776 | 15.88 | ||||||

| Trichocerca similis Wierzejski, 1893 | 48.27 | ||||||

| Trichocerca stylata Gosse, 1851 | 11.93 | ||||||

| Crustacea | |||||||

| Alona costata Sars, 1862 | 16.70 | ||||||

| Bosmina longirostris (O.F. Müller, 1776) | 30.25 | ||||||

| Bosmina longispina Leydig, 1860 | 21.64 | ||||||

| Chydorus sphaericus (O.F. Müller, 1776) | 16.64 | ||||||

| Daphnia cuculata Sars, 1862 | 19.44 | ||||||

| Daphnia galeata Sars, 1863 | 9.91 | ||||||

| Diaphanosoma brachyurum (Liévin 1848) | 33.28 | ||||||

| Diaphanosoma sp. | 12.10 | ||||||

| Moina brachiata (Jurine, 1820) | |||||||

| Moina micrura Kurz, 1874 | 12.63 | ||||||

| Scapholeberis mucronata (O. F. Muller, 1776) | 14.12 | ||||||

| Nauplii | 35.08 | ||||||

| Copepodites | 23.58 | 31.27 | |||||

| Cyclopida g.sp. | 20.01 |

| CTSI | TSIROT | TSICR | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean ± SD | TS | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | TS | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | TS | ||

| Colentina | r | 43.45 | 58.03 | 51.7 ± 5.28 | E | 21.67 | 44.70 | 34.21 ± 7.83 | M | 24.24 | 32.57 | 27.94 ± 2.98 | M |

| Crevedia | r | 35.39 | 74.97 | 68.1 ± 13.32 | E | 43.44 | 56.89 | 50.96 ± 5.75 | M | 31.05 | 44.57 | 37.81 ± 5.12 | M |

| Mogoșoaia | pu | 66.17 | 76.07 | 72.43 ± 3.5 | H | 44.07 | 61.29 | 54.55 ± 4.62 | E | 0.00 | 57.38 | 44.26 ± 14.76 | M-E |

| Plumbuita | u | 42.13 | 74.33 | 67.72 ± 7.21 | E | 42.49 | 63.16 | 55.03 ± 5.33 | E | 36.29 | 65.71 | 49.41 ± 7.61 | M-E |

| Fundeni | u | 64.20 | 77.44 | 71.97 ± 3.08 | H | 43.43 | 62.00 | 55.63 ± 5 | E | 38.64 | 79.40 | 55.77 ± 11.22 | E |

| Cernica | pu | 55.49 | 76.41 | 68.83 ± 6.23 | E | 45.56 | 61.00 | 53.53 ± 4.07 | E | 38.44 | 68.64 | 54.47 ± 10.65 | E |

| Cernica (river) | r | 62.58 | 73.41 | 70.06 ± 3.79 | H | 55.24 | 66.21 | 59.76 ± 3.91 | E | 0.00 | 57.68 | 44.19 ± 18.44 | M-E |

| RUEROT | RUECR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD |

| Colentina | 0.75 | 4.74 | 2.87 ± 1.5 | 0.42 | 2.54 | 1.9 ± 0.73 |

| Crevedia | 2.40 | 8.37 | 4.56 ± 1.73 | 1.98 | 6.61 | 3.73 ± 1.41 |

| Mogoșoaia | 2.49 | 5.75 | 4.43 ± 0.87 | 0.51 | 6.64 | 4.12 ± 2.1 |

| Plumbuita | 2.83 | 9.02 | 5.38 ± 1.37 | 3.28 | 7.69 | 5.32 ± 1.27 |

| Fundeni | 3.20 | 6.79 | 5.09 ± 1.02 | 3.88 | 9.31 | 5.98 ± 1.67 |

| Cernica | 2.96 | 7.34 | 5.52 ± 1.33 | 3.43 | 8.55 | 6.06 ± 1.94 |

| Cernica (river) | 4.29 | 6.82 | 5.52 ± 0.83 | 0.40 | 6.96 | 5.00 ± 2.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Florescu, L.I.; Moldoveanu, M.M.; Dumitrache, C.A.; Catana, R.D. Zooplankton Indicators of Ecological Functioning Along an Urbanisation Gradient. Diversity 2026, 18, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010058

Florescu LI, Moldoveanu MM, Dumitrache CA, Catana RD. Zooplankton Indicators of Ecological Functioning Along an Urbanisation Gradient. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlorescu, Larisa I., Mirela M. Moldoveanu, Cristina A. Dumitrache, and Rodica D. Catana. 2026. "Zooplankton Indicators of Ecological Functioning Along an Urbanisation Gradient" Diversity 18, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010058

APA StyleFlorescu, L. I., Moldoveanu, M. M., Dumitrache, C. A., & Catana, R. D. (2026). Zooplankton Indicators of Ecological Functioning Along an Urbanisation Gradient. Diversity, 18(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010058