Chromosomal Architecture, Karyotype Profiling and Evolutionary Dynamics in Aleppo Oak (Quercus infectoria Oliv.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

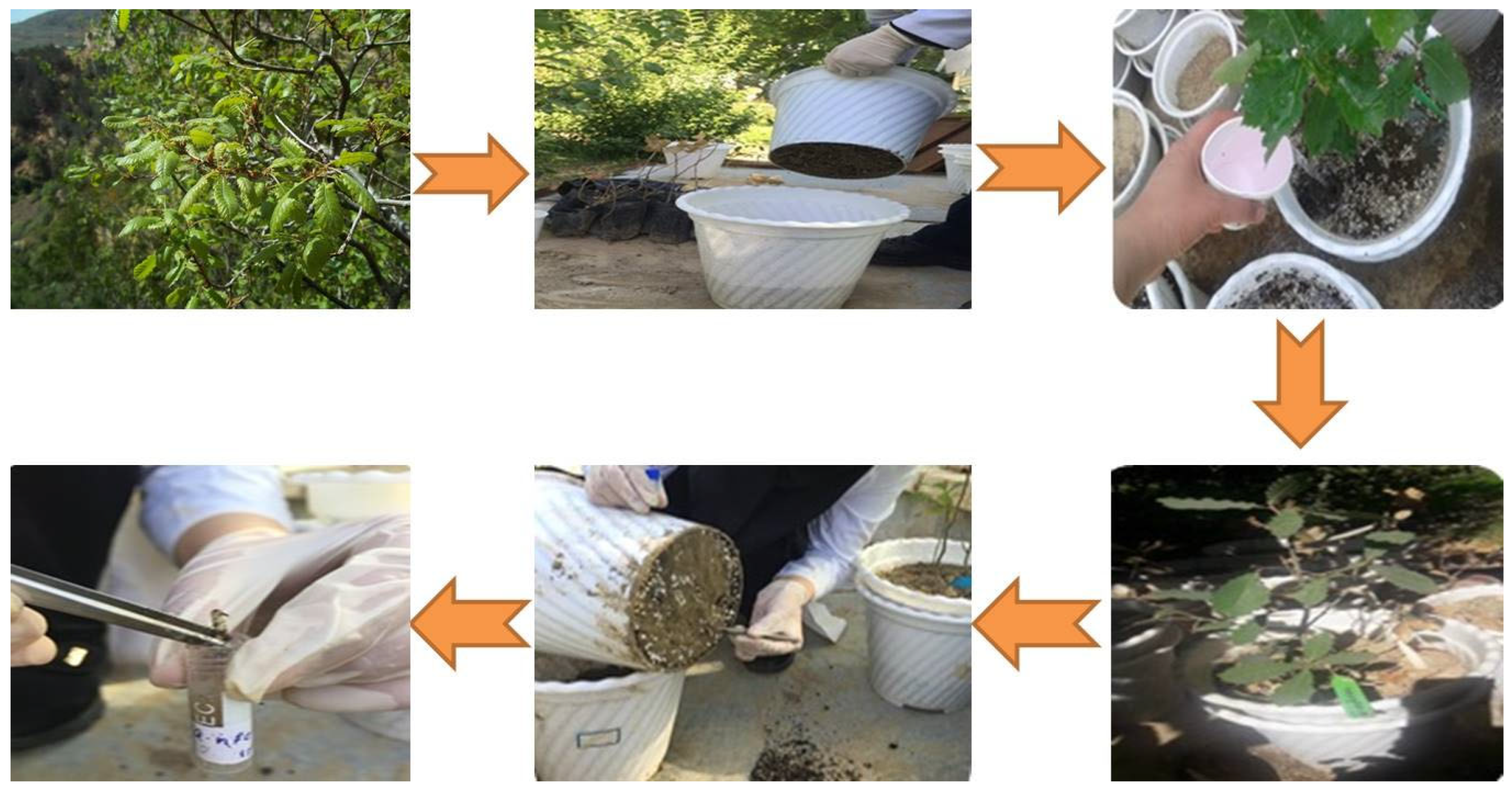

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

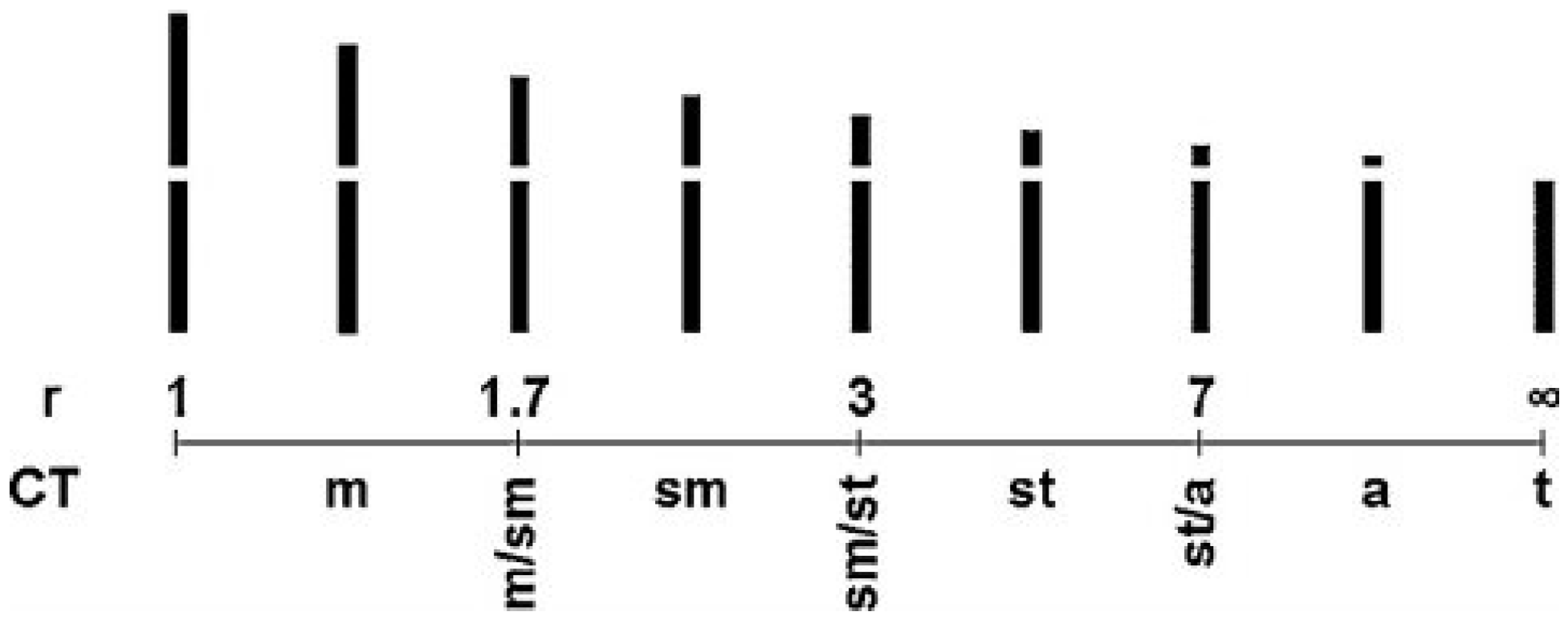

2.2. Methods

3. Results

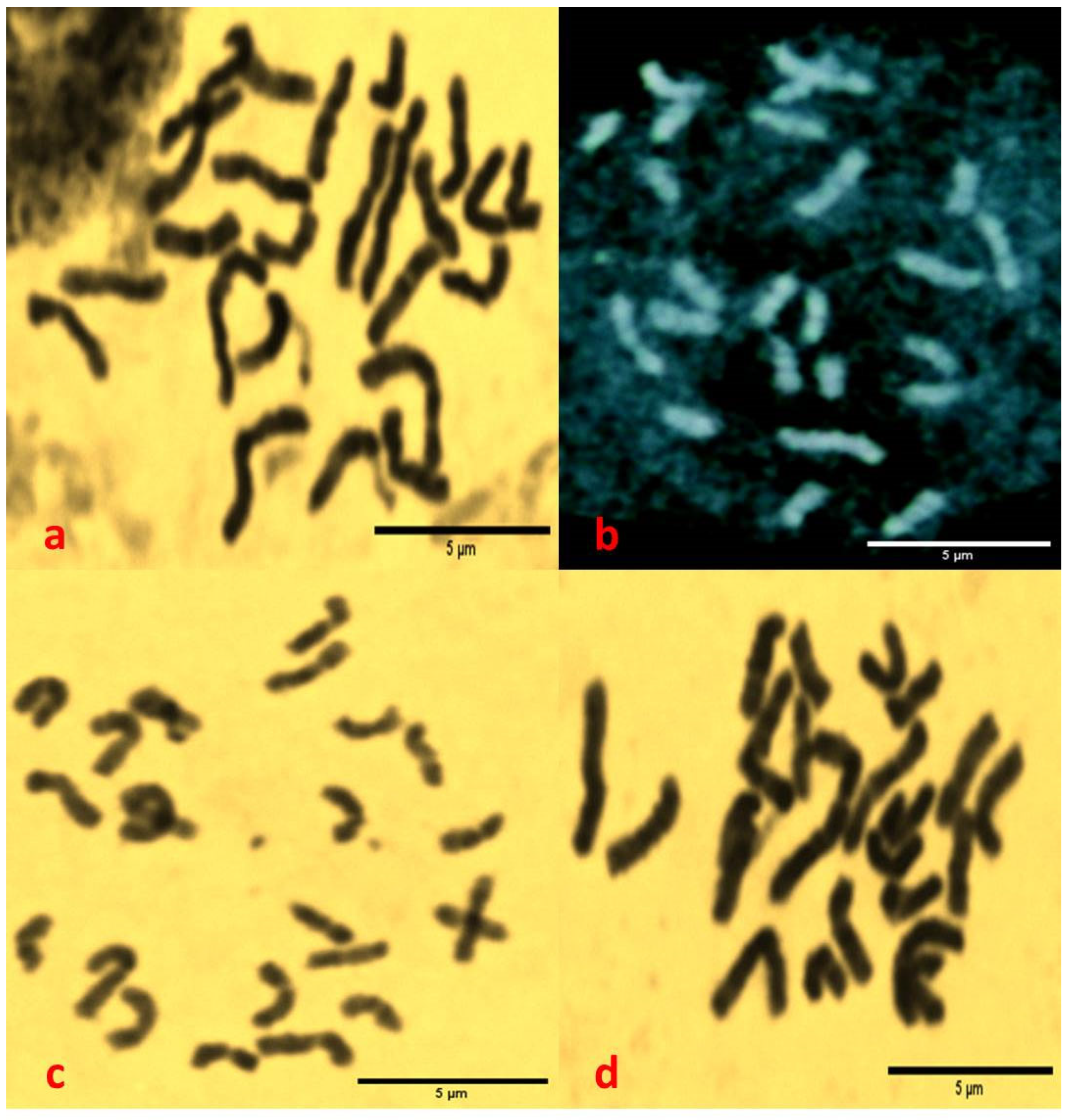

3.1. Determining and Optimizing the Appropriate Guidelines for Better Viewing of Chromosomes

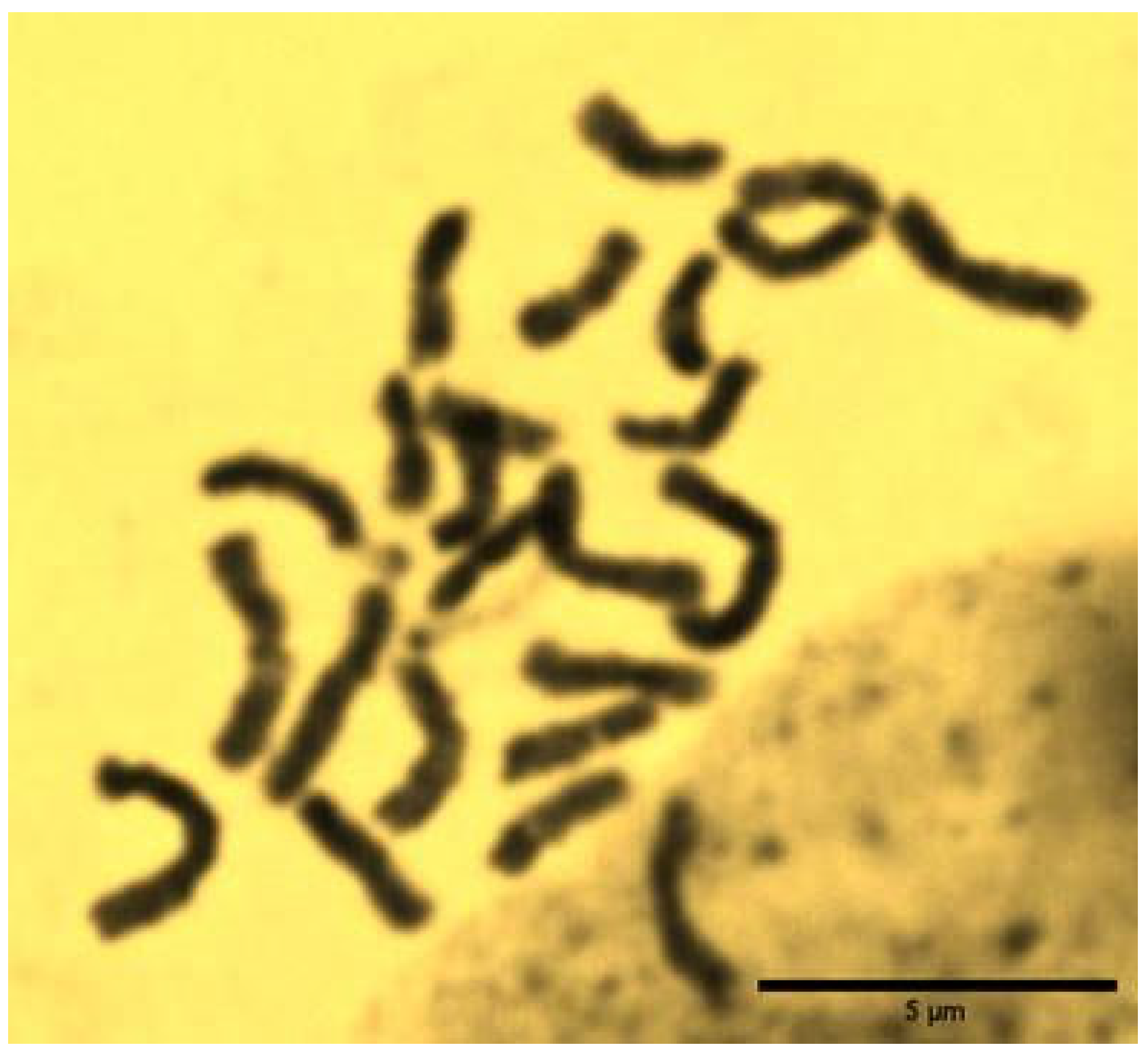

3.2. The Results of Microscopic Examination, Chromosomal Counting and Determination of Karyotype

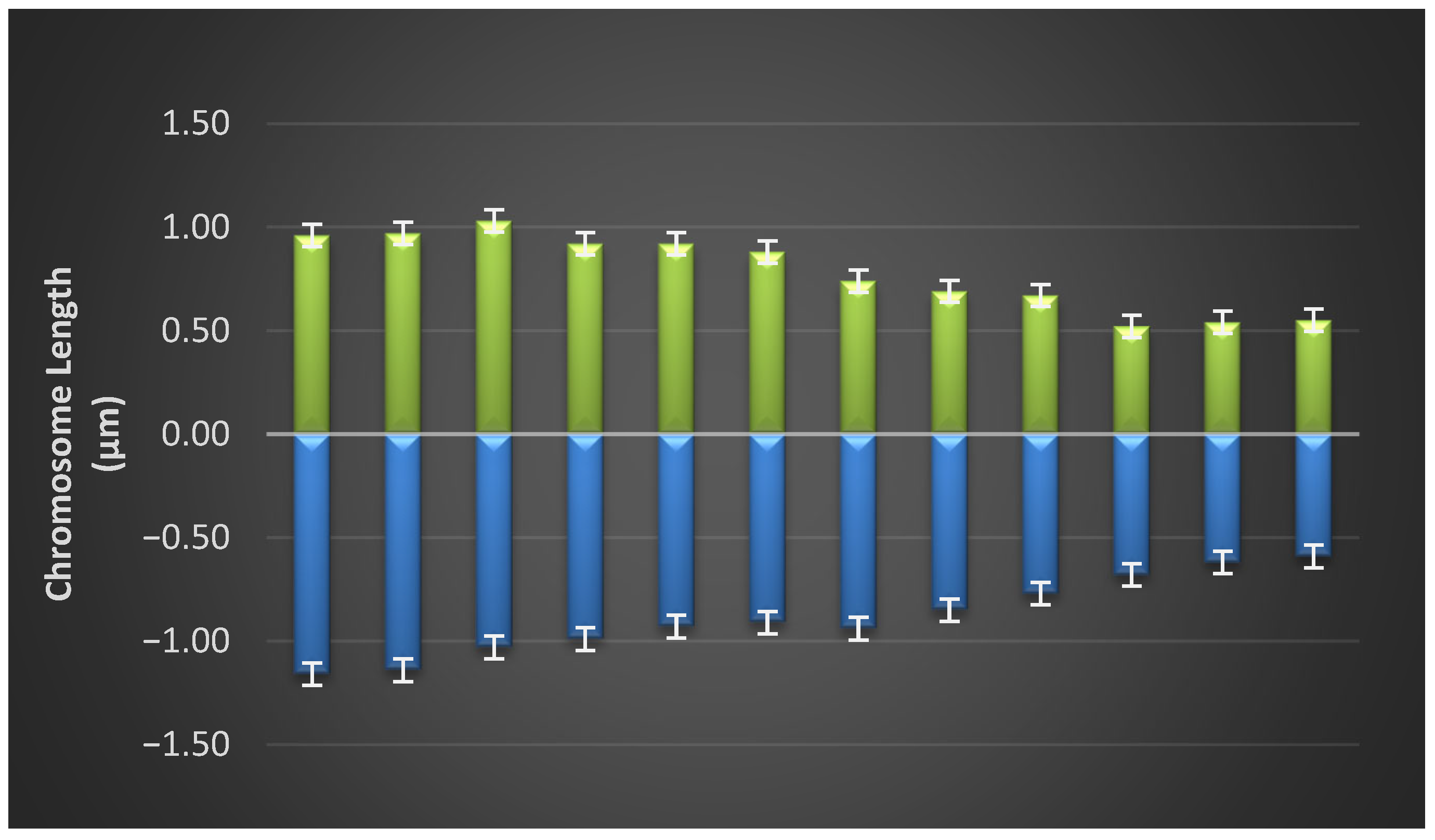

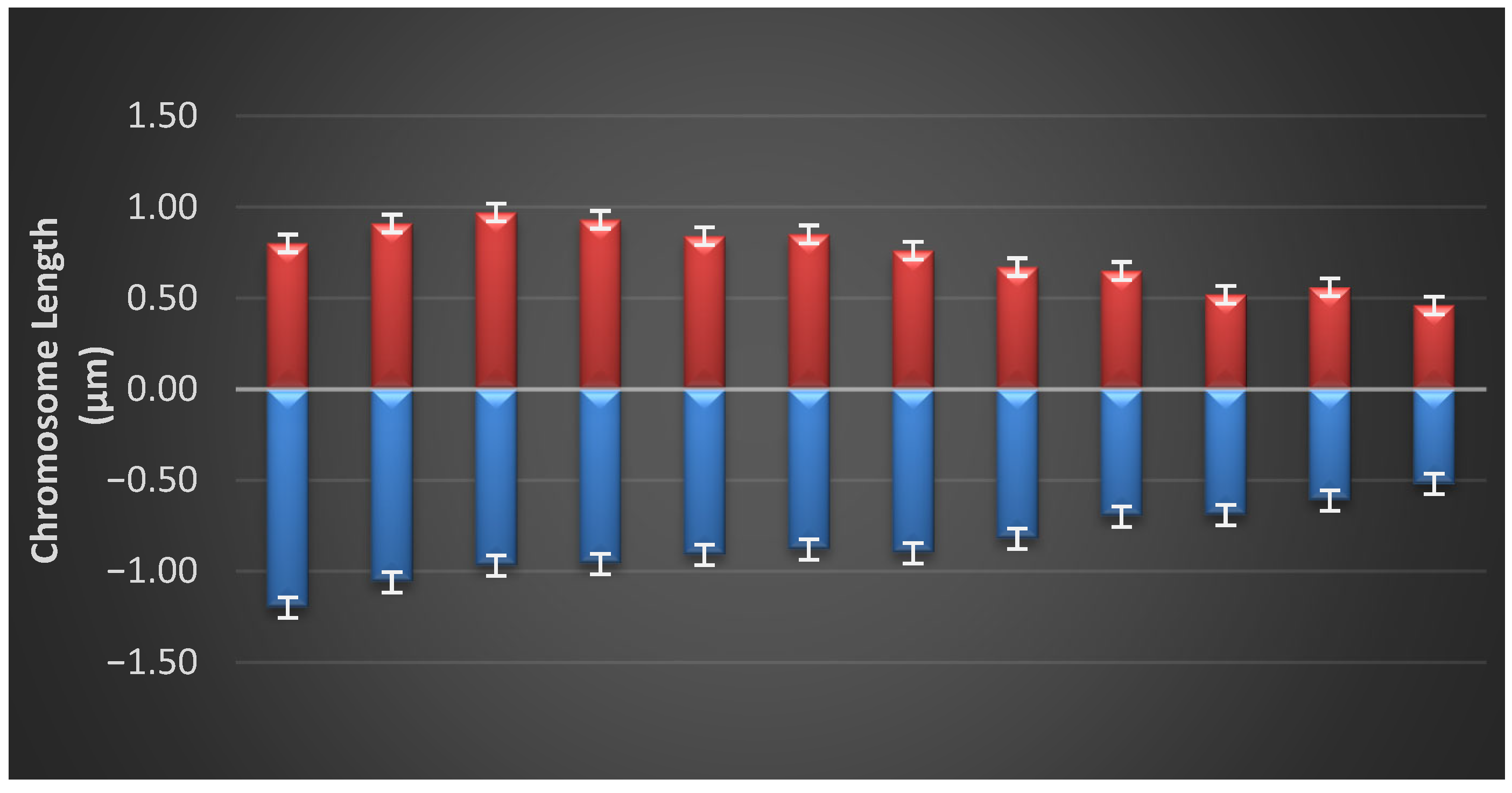

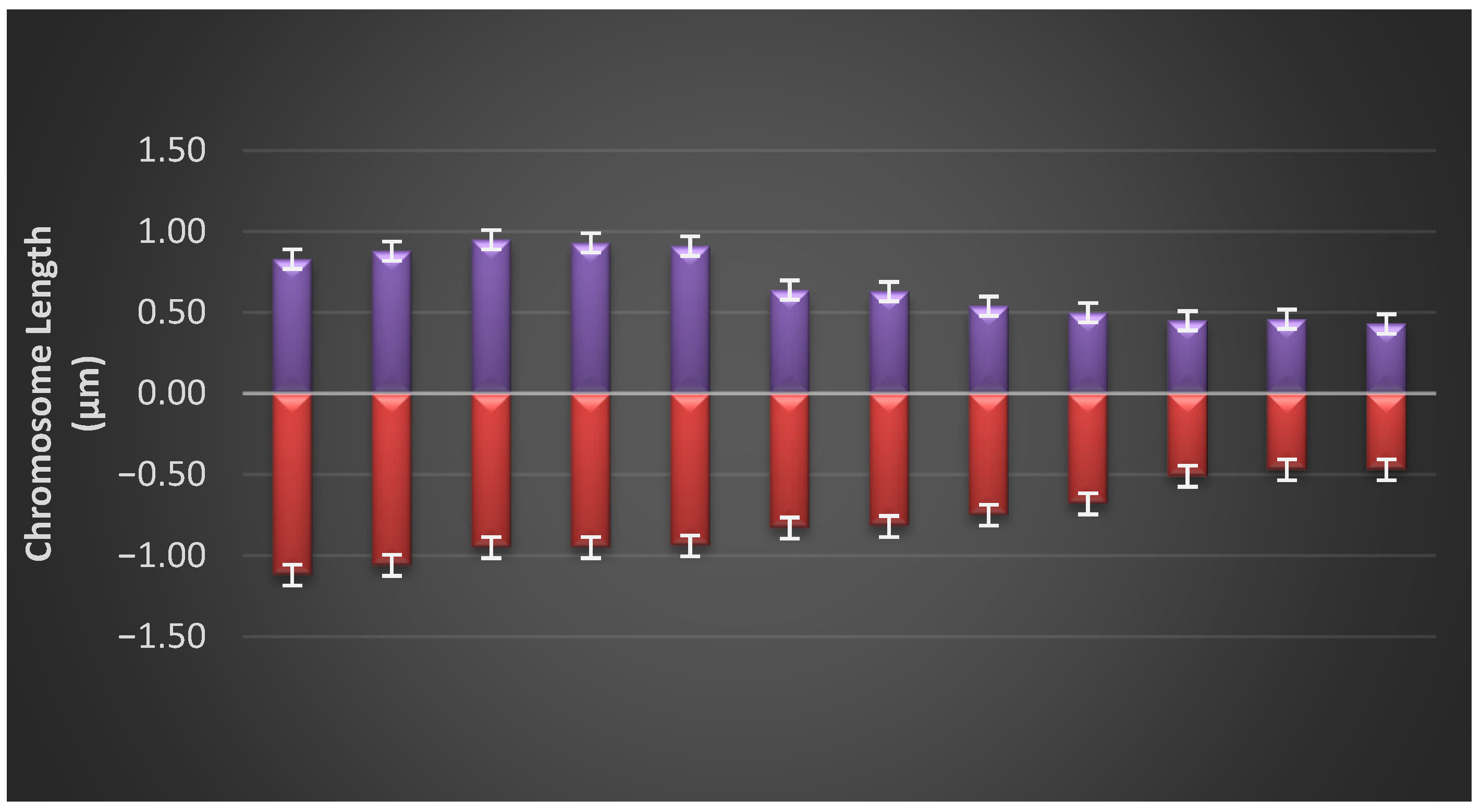

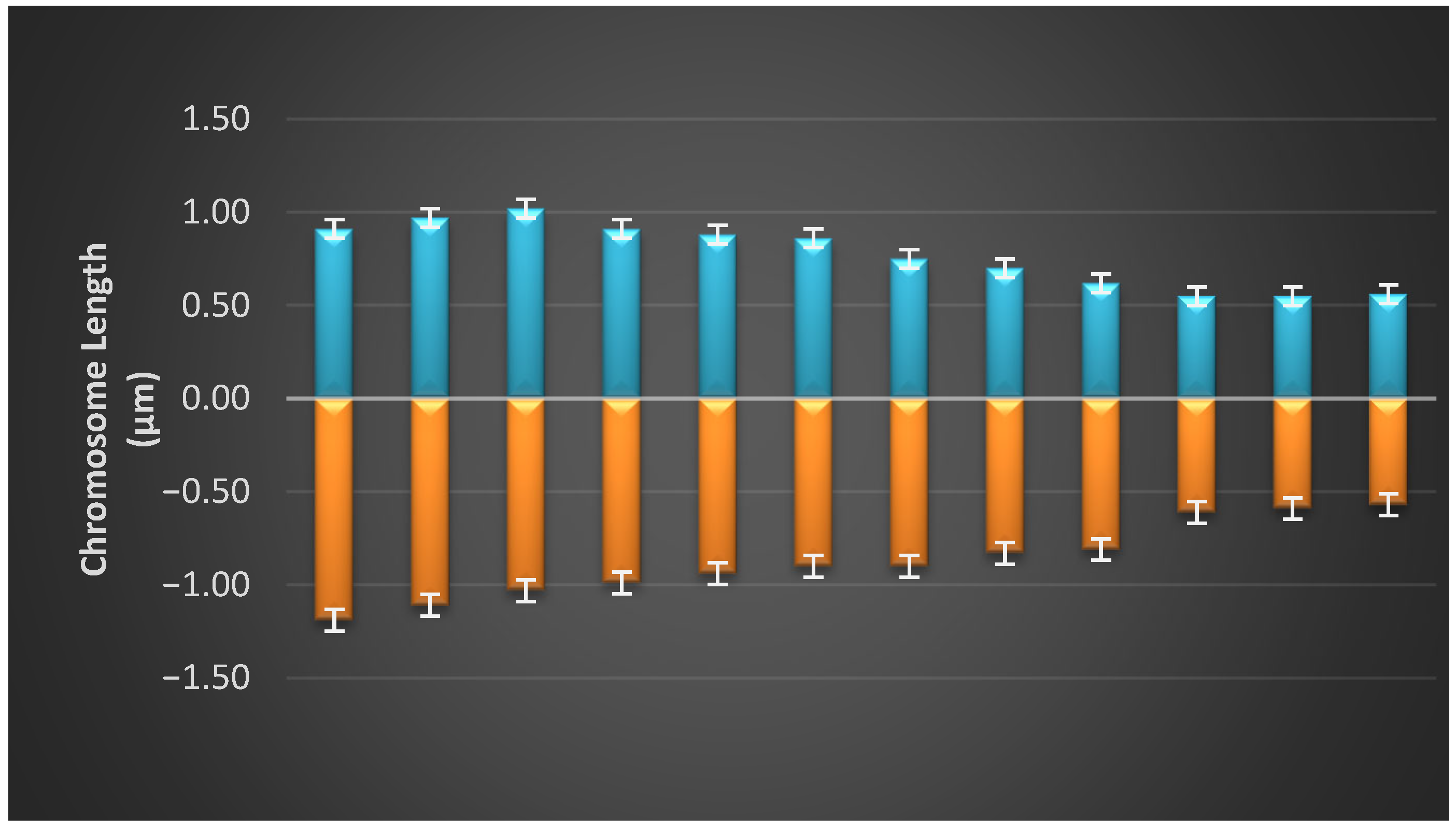

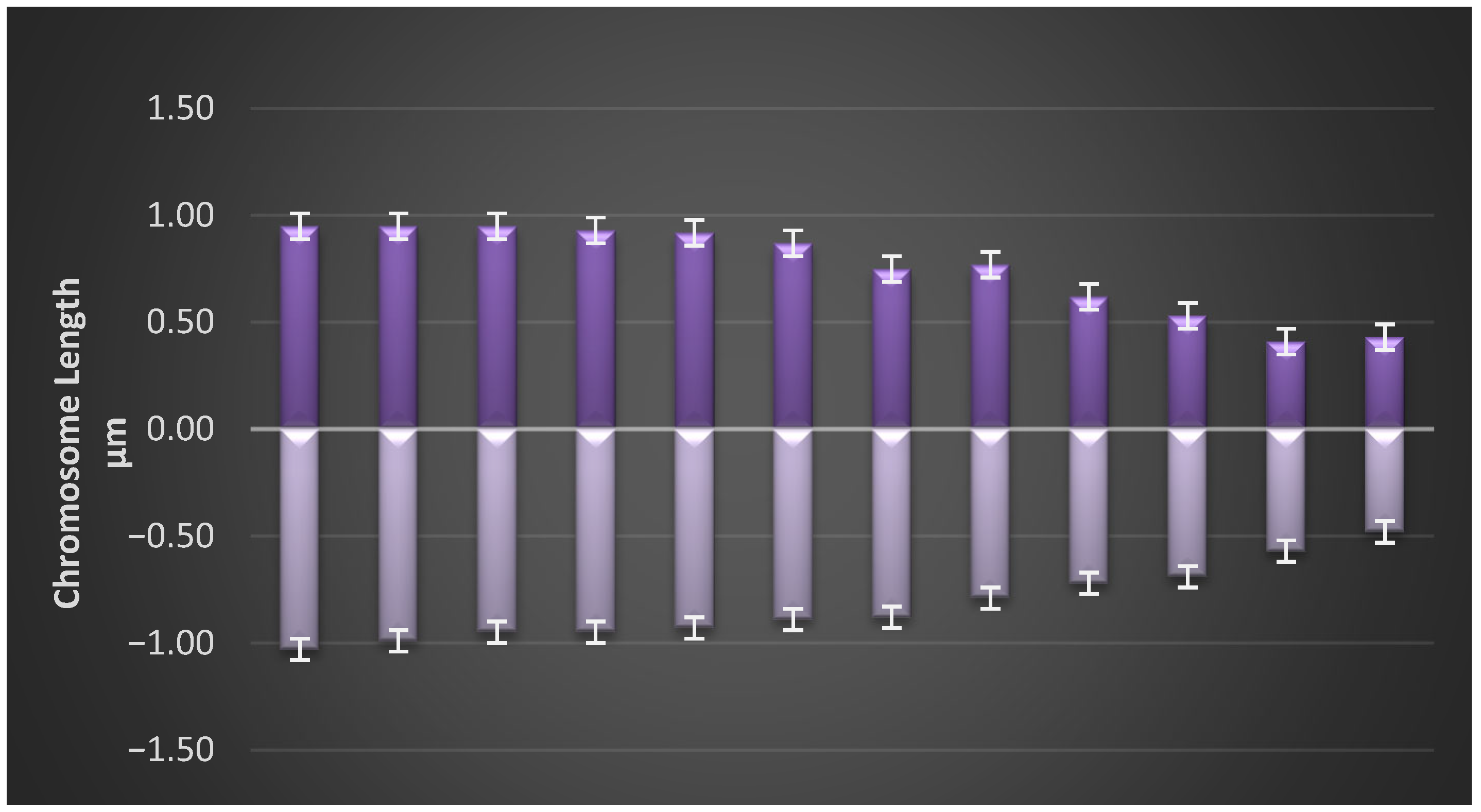

3.3. Idiogram of Each Population

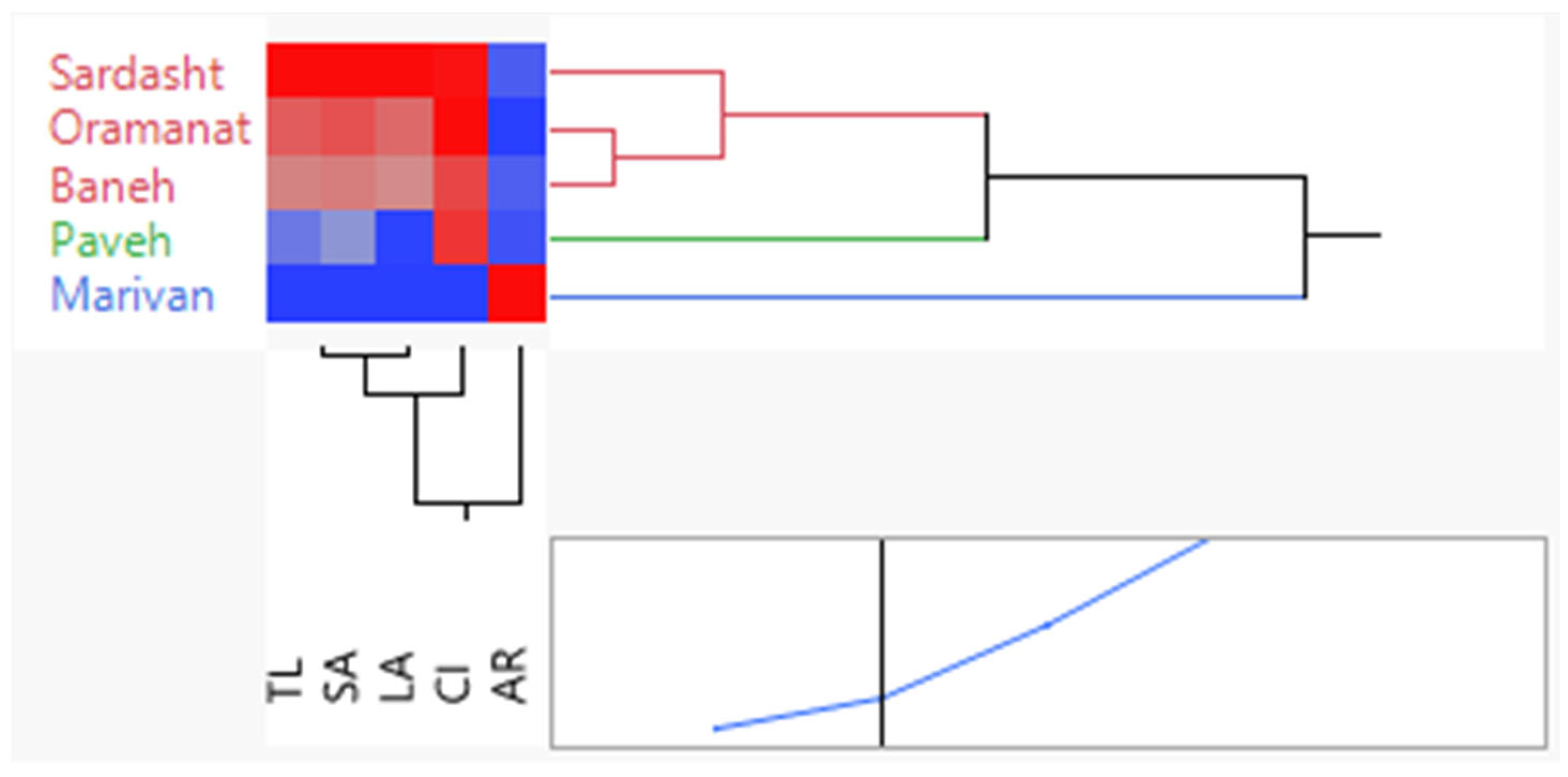

3.4. Variance Analysis of Karyotype Morphological Parameters

3.5. Mean Comparisons of Karyotype Morphological Traits

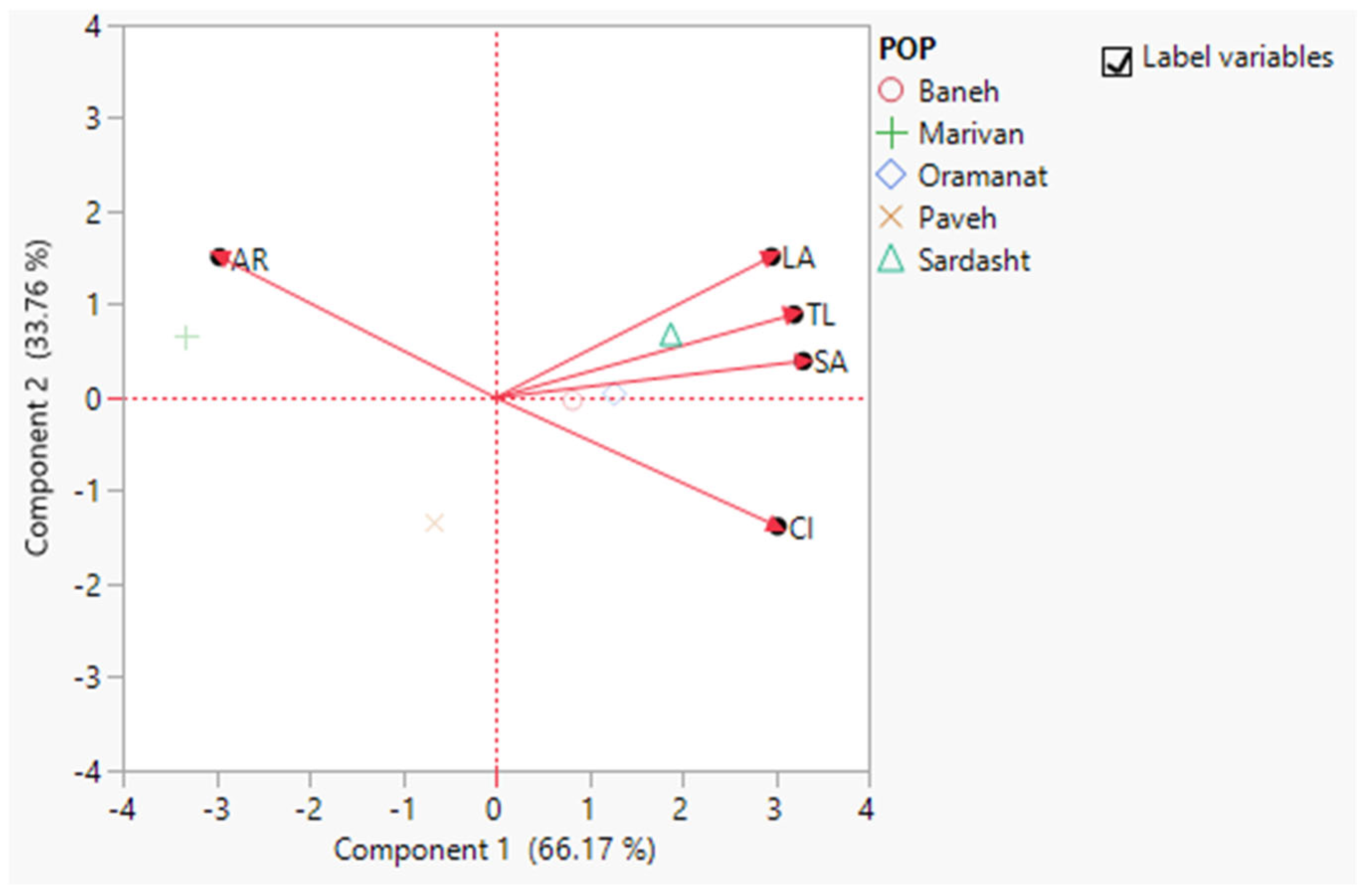

3.6. Principal Component Analysis Based on All Characteristics of Each Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, A.A.; Qadir, S.A.; Tahir, N.A.R. Genetic Variation and Structure Analysis of Iraqi Valonia Oak (Quercus aegilops L.) Populations Using Conserved DNA-Derived Polymorphism and Inter-Simple Sequence Repeats Markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Wang, L.; Xian, Y.; Xie, X.M.; Li, W.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R.-G.; Qin, X.; Li, D.-Z.; Jia, K.H. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the Chinese cork oak (Quercus variabilis). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1001583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J. Diversity, distribution and ecosystem services of the North American oaks. Int. Oaks 2016, 27, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Plomion, C.; Aury, J.-M.; Amselem, J.; Leroy, T.; Murat, F.; Duplessis, S.; Faye, S.; Francillonne, N.; Labadie, K.; Le Provost, G.; et al. Oak genome reveals facets of long lifespan. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sork, V.L.; Bramble, J.; Sexton, O. Ecology of mast-fruiting in three species of North American deciduous oaks. Ecology 1993, 74, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugger, P.F.; Fitz-Gibbon, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Sork, V.L. Species-wide patterns of DNA methylation variation in Quercus lobata and their association with climate gradients. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 1665–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellstab, C.; Zoller, S.; Walthert, L.; Lesur, I.; Pluess, A.R.; Graf, R.; Bodénès, C.; Sperisen, C.; Kremer, A.; Gugerli, F. Signatures of local adaptation in candidate genes of oaks (Quercus spp.) with respect to present and future climatic conditions. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 5907–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sork, V.L.; Squire, K.; Gugger, P.F.; Steele, S.E.; Levy, E.D.; Eckert, A.J. Landscape genomic analysis of candidate genes for climate adaptation in a California endemic oak, Quercus lobata. Am. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, F.K.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Ueno, S.; de Lafontaine, G. Contrasted patterns of local adaptation to climate change across the range of an evergreen oak, Quercus aquifolioides. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 2377–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, K.C. Global and neotropical distribution and diversity of oak (genus Quercus) and oak forests. In Ecology and Conservation of Neotropical Montane Oak Forests; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Simeone, M.C.; Grimm, G.W.; Papini, A.; Vessella, F.; Cardoni, S.; Tordoni, E.; Piredda, R.; Franc, A.; Denk, T. Plastome data reveal multiple geographic origins of Quercus Group Ilex. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón, E.; Averyanova, A.; Kvaček, Z.; Momohara, A.; Pigg, K.B.; Popova, S.; Postigo-Mijarra, J.M.; Tiffney, B.H.; Utescher, T.; Zhou, Z.K. The fossil history of Quercus. In Oaks Physiological Ecology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 39–105. [Google Scholar]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 2021; Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 19 January 2026).

- Borgardt, S.J.; Pigg, K.B. Anatomical and developmental study of petrified Quercus (Fagaceae) fruits from the Middle Miocene, Yakima Canyon, Washington, USA. Am. J. Bot. 1999, 86, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepet, W.L. Status of certain families of the Amentiferae during the Middle Eocene and hypotheses regarding evolution of wind pollination. In Paleobotany, Paleoecology and Evolution; Niklas, K.J., Ed.; Arcler Press: Burlington, ON, Canada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.H. Evolution of the Fagaceae: The implications of foliar features. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1986, 73, 228–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarvand, M.; Assadi, M.; Abbasi, S. A Taxonomic Revision on Aquatic Vascular Plants in Iran. Rostaniha 2022, 23, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Akhani, H. Flora Iranica: Facts and Figures and a List of Publications by K. H. Rechinger on Iran and Adjacent areas. Rostaniha 2006, 7, 19–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, N.M.A. Oaks of Iran; Azad-Peyma Press: Tehran, Iran, 2013; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Pirbaluti, F.G.; Saravi, A.T.; Arani, A.M. Karyotypic analysis of Quercus infectoria G. Oliver. Iran. J. Rangel. For. Plant Breed. Genet. Res. 2017, 2, 324–335. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P.H. (Ed.) Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1970; pp. 1965–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Z.; Raynal, D.J. Biodiversity and conservation of Turkish forests. Biol. Conserv. 2001, 97, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, Y. Étude de la végétation steppique des montagnes d’Aydos situées au Nord-Ouest d’Ankara. Ecol. Mediterr. 1990, 16, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharpour, F.; Seyedi, N.; Najafi, S. Karyological and Chromosome Analysis of Quercus libani in Iran. YYU J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 29, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, H. Forests, Trees and Small Trees of Iran; Yazd University Press: Yazd, Iran, 2002; 806p. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, H.; Razban Hagigat, A.; Hesamzade Hejazi, S.M. Karyotype studies on three Astragalus species. J. Pajouhesh Va Sazandgi 2006, 73, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, S.; Ulker, M.; Oral, E.; Tuncturk, R.; Tuncturk, M.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Perveen, K.; Poczai, P.; Cseh, A. Estimation of nuclear DNA content in some Aegilops species: Best analyzed using flow cytometry. Genes 2022, 13, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, S.; Ulker, M.; Altuner, F.; Oral, E.; Ozdemir, B.; Jamal, S.S.; Selem, E. Karyological analysis on wheat tir (Triticum aestivum var. aestivum L. spp. Leucospermum Körn.) ecotypes in Lake Van Basin, Turkey. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2022, 18, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Sheidai, M.; Masoumii, A.R.; Pakravan, M. Karyological studies of some Astragalus taxa. The Nucleus 1996, 39, 111–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hesamzade, S.M.; Ziaei Nasab, M. Cytogenetics study on Hedysarum species. Iran. J. Rangel. For. Plant Breed. Genet. Res. 2007, 15, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mabberley, D.J. The Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of Higher Plants; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, M.; Pourbabaei, H.; Atar Roushan, S. Natural regeneration of Persian oak (Quercus brantii) between ecological species group in Kurdo-Zagros region. Iran. J. Biol. 2011, 24, 578–592. [Google Scholar]

- Rechinger, K.H. Flora Iranica; Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt: Graz, Austria, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Javanshir Khoie, K. Les chênes de l’Iran. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 1967; 221p. [Google Scholar]

- Mozafarian, V. Trees and Shrubs of Iran; Farhang-e Moaser Press: Tehran, Iran, 2004; 1003p. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi Hajii Pamogh, K.; Seyedi, N.; Ghasemzade, R.; Banj Shafiei, A. The effect of changes in longitude, latitude and altitude above sea level on Iranian oak seed size. For. Res. Dev. 2025, 11, 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Statgraphics Technologies, Inc. STATGRAPHICS Centurion, version 19, Computer Software. Statgraphics Technologies, Inc.: The Plains, VA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.statgraphics.com (accessed on 19 January 2026).

- Romero-Zarco, C. A new method for estimating karyotype asymmetry. Taxon 1986, 35, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levan, A.; Fredga, K.; Sandberg, A.A. Nomenclature for centromeric position on chromosomes. Hereditas 1964, 52, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, G.L. Chromosomal Evolution in Higher Plants; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1971; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Ebadi-Almas, D.; Karimzadeh, G.; Mirzaghaderi, G. Karyotypic variation and karyomorphology in Iranian endemic ecotypes of Plantago ovata Forsk. Cytologia 2012, 77, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, G.; Danesh-Gilevaei, M.; Aghaalikhani, M. Karyotypic and nuclear DNA variations in Lathyrus sativus (Fabaceae). Caryologia 2011, 64, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agayev, Y.M. New features in karyotype structure and origin of saffron Crocus sativus L. Cytology 2002, 67, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agayev, Y.M.; Zarifi, E.; Fernandez, J.A. A study of karyotypes in the Crocus sativus L. aggregate and origin of cultivated saffron. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Saffron, Kozani, Greece, 20–23 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, S. Türkiye ve İran Kökenli Bazı Aegilops Türlerinin Karyotip Karakterizasyonu. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, S.; Anakhatoon, E.Z.; Bırsın, M.A. Karyotype characterisation of reputed variety of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) in West Azerbaijan–Iran. J. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2013, 7, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, S.; Tuncturk, R.; Tuncturk, M.; Seyyedi, N. Karyosystematic study on some almond and peach species in Iran. YYU J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 25, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zarifi, E.; Güloğlu, D. An improved Aceto-Iron-Haematoxylin staining for mitotic chromosomes in Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas L.). Caryologia 2016, 69, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Amirnia, R.; Manesh, M.F.; Danesh, Y.R.; Najafi, S.; Seyyedi, N.; Ghiyasi, M. Karyological study on Teheran ecotype of Dracocephalum moldavica L. J. Mol. Biol. Biotechnol. 2017, 1, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Amirnia, R.; Varzeghan, H.A.; Danesh, Y.R.; Najafi, S.; Seyyedi, N.; Ghiyasi, M. Karyological study on Urmia ecotype of Dracocephalum moldavica L. J. Mol. Biol. Biotechnol. 2017, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, S.; Tuncturk, R.; Tuncturk, M.; Seyyedi, N. Chromosome analysis of Quercus castaneifolia. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2021, 17, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Kulaz, H.; Najafi, S.; Tuncturk, M.; Tuncturk, R.; Yilmaz, H. Chromosome analysis of some Phaseolus vulgaris L. genotypes in Turkey. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2022, 51, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulaz, H.; Najafi, S.; Tuncturk, R.; Tuncturk, M.; Albalawi, M.A.; Alalawy, A.I.; Oyouni, A.A.A.; Alasmari, A.; Poczai, P.; Sayyed, R.Z. Analysis of nuclear DNA content and karyotype of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Genes 2022, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, S.; Mohammadi Fallah, A.; Najafi, S. Application of Allium hirtifolium for the selection process in architecture and environmental sciences. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2022, 18, 927–938. [Google Scholar]

- Taghvaei, M.; Maleki, H.; Najafi, S.; Hassani, H.S.; Danesh, Y.R.; Farda, B.; Pace, L. Using chromosomal abnormalities and germination traits for the assessment of tritipyrum amphiploid lines under seed-aging and germination priming treatments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, S. Aegilops crassa cytotypes in some regions of Türkiye. Plants 2024, 13, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal component analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1094–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi, H.Z.; Şahin, E.; Haliloğlu, K. Principal components analysis of some F1 sunflower hybrids at germination and early growth stage. J. Agric. Fac. Atatürk Univ. 2011, 42, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kroonenberg, P.M. Introduction to biplots for G × E tables. Res. Rep. 1995, 51, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.H. Polyploidy in species populations. In Polyploidy: Biological Relevance; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 103–144. [Google Scholar]

- Tabandeh Saravi, A.; Tabari, M.; Mirzaie-Nodoushan, H.; Espahbodi, K.; Asadi-Corom, F. Karyotypic analysis on Quercus castaneifolia of north Iran. IJRF Plant Breed. Genet. Res. 2012, 20, 226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Stairs, G.R. Microsporogenesis and embryogenesis in Quercus. Bot. Gaz. 1964, 125, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoldos, V.; Papes, D.; Cerbah, M.; Panaud, O.; Besendorfer, V.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S. Molecular-cytogenetic studies reveal conserved genome organization among 11 Quercus species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 99, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, Y.; Yonezawa, Y. Karyotype analysis of fifteen Quercus species in Japan. Chromosome Sci. 2004, 8, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Aykut, Y.; Uslu, E.; Babaç, M.T. Cytogenetic studies on Quercus L. species belonging to Ilex and Cerris sections in Turkey. Caryologia 2011, 64, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykut, Y. Phylogenetic relationships of the genus Quercus L. (Fageceae) from three different section. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 2265–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A. Karyomorphology of some Quercus species in Turkey. Caryologia 2018, 71, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A. Cytogenetic Relationships of Turkish Oaks. In Cytogenetics—Past, Present and Future Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naujoks, G.; Hertel, H.; Ewald, D. Characterization and propagation of an adult triploid pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.). Silvae Genet. 1995, 44, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Butorina, A.K. Cytogenetic study of diploid and spontaneous triploid oaks. Ann. Des Sci. For. 1993, 50, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dzialuk, A.; Chybicki, I.; Welc, M.; Sliwinska, E.; Burczyk, J. Presence of triploids among oak species. Ann. Bot. 2007, 99, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerico, S.; Bianco, P.; Schirone, B. Karyotype analysis in Quercus spp. Silvae Genet. 1995, 44, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chokchaichamnankit, P.; Chulalaksananukul, W.; Phengklai, C.; Anamthawat-Jonsson, K. Karyotypes of some species of Castanopsis, Lithocarpus and Quercus (Fagaceae) from Khun Mae Kuang Forest in Chiang Mai province, northern Thailand. Thai For. Bull. 2007, 35, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Aykut, Y.; Uslu, E.; Babaç, M.T. Karyological studies on four Quercus species in Turkey. Caryologia 2008, 61, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yousefi, V.; Najafi, A.; Zebarjadi, A.; Safari, H. Karyotype characterization of Thymus species in Iran. J. Plant Genet. Res. 2013, 1, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Formula |

|---|---|

| Short arm (S) | Distance between the end of the short arm to centromere (µm) |

| Long arm (L) | Distance between the end of the long arm to centromere (µm) |

| Total length (TL) | TL = LAi + SAi (µm) |

| Centromer index (CI) | × 100 (%) |

| Intrachromosomal Asymmetry Index (A1) | |

| Interchromosomal Asymmetry Index (A2) |

| Ratio | Proportion of Chromosomes with Arm Ratio > 2:1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest/Smallest | 1.00 (1) | 0.99–0.51 (2) | 0.50–0.01 (3) | 0.00 (4) |

| <2:1 (A) | 1A | 2A | 3A | 4A |

| 2:1–4:1 (B) | 1B | 2B | 3B | 4B |

| >4:1 (C) | 1C | 2C | 3C | 4C |

| S.O.V | df | Mean of Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | LA | SA | Arm Ratio | CI | ||

| Location | 4 | 5.68 ** | 1.096 ** | 1.96 ** | 0.008 ns | 3.69 ns |

| Error | 10 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.007 | 3.57 |

| Total | 14 | |||||

| Location | TL | LA | SA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21.43 a | 11.27 a | 10.17 a |

| 2 | 19.19 bc | 10.08 ab | 9.11 b |

| 3 | 17.63 c | 9.61 b | 8.01 c |

| 4 | 19.72 ab | 10.20 ab | 9.52 ab |

| 5 | 19.00 bc | 10.24 ab | 8.76 bc |

| PC1 | PC2 | |

|---|---|---|

| TL | 0.463 | 0.328 |

| LA | 0.428 | 0.555 |

| SA | 0.477 | 0.144 |

| AR | −0.428 | 0.554 |

| CI | 0.437 | −0.506 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.308 | 1.688 |

| Percent | 66.169 | 33.762 |

| Cumulative Percent | 66.169 | 99.931 |

| Chi Square | 144.125 | 109.86 |

| DF | 9.444 | 9.349 |

| Prob > ChiSq | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Najafi, S.; Seyedi, N.; Özdemir, B.; Zeinalzadeh-Tabrizi, H.; Farda, B.; Pace, L. Chromosomal Architecture, Karyotype Profiling and Evolutionary Dynamics in Aleppo Oak (Quercus infectoria Oliv.). Diversity 2026, 18, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010059

Najafi S, Seyedi N, Özdemir B, Zeinalzadeh-Tabrizi H, Farda B, Pace L. Chromosomal Architecture, Karyotype Profiling and Evolutionary Dynamics in Aleppo Oak (Quercus infectoria Oliv.). Diversity. 2026; 18(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleNajafi, Solmaz, Nasrin Seyedi, Burak Özdemir, Hossein Zeinalzadeh-Tabrizi, Beatrice Farda, and Loretta Pace. 2026. "Chromosomal Architecture, Karyotype Profiling and Evolutionary Dynamics in Aleppo Oak (Quercus infectoria Oliv.)" Diversity 18, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010059

APA StyleNajafi, S., Seyedi, N., Özdemir, B., Zeinalzadeh-Tabrizi, H., Farda, B., & Pace, L. (2026). Chromosomal Architecture, Karyotype Profiling and Evolutionary Dynamics in Aleppo Oak (Quercus infectoria Oliv.). Diversity, 18(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010059