Climate Zones Modulate Deep Chlorophyll Maxima in Middle-Latitude Lakes via Thermocline Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Selection and Literature Search

2.2. Data Extraction and Harmonization

2.3. Final Dataset and Lake Classification

2.4. Derived Parameters and Definitions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

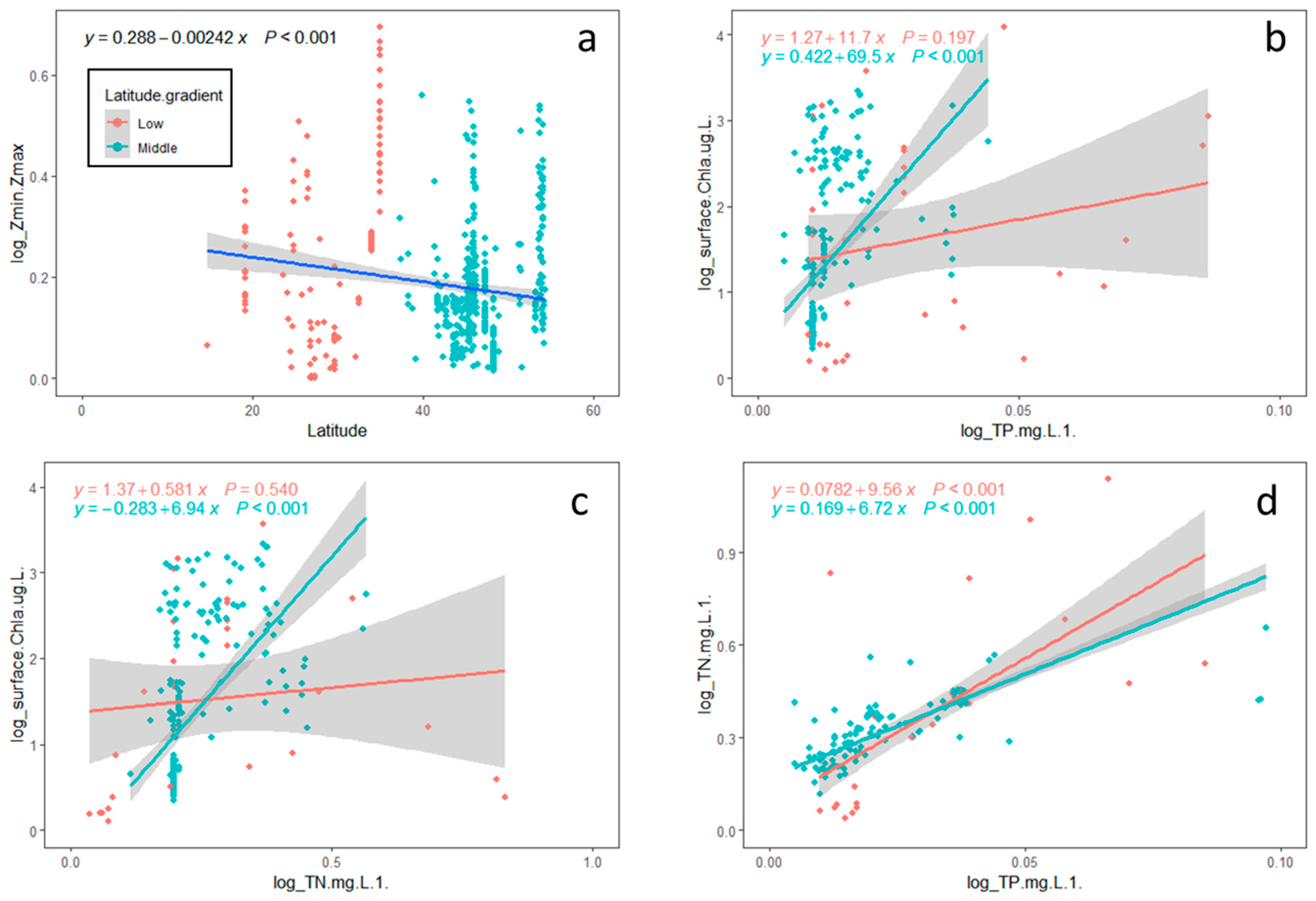

3.1. Relationships Between Environmental Variables and Thermocline

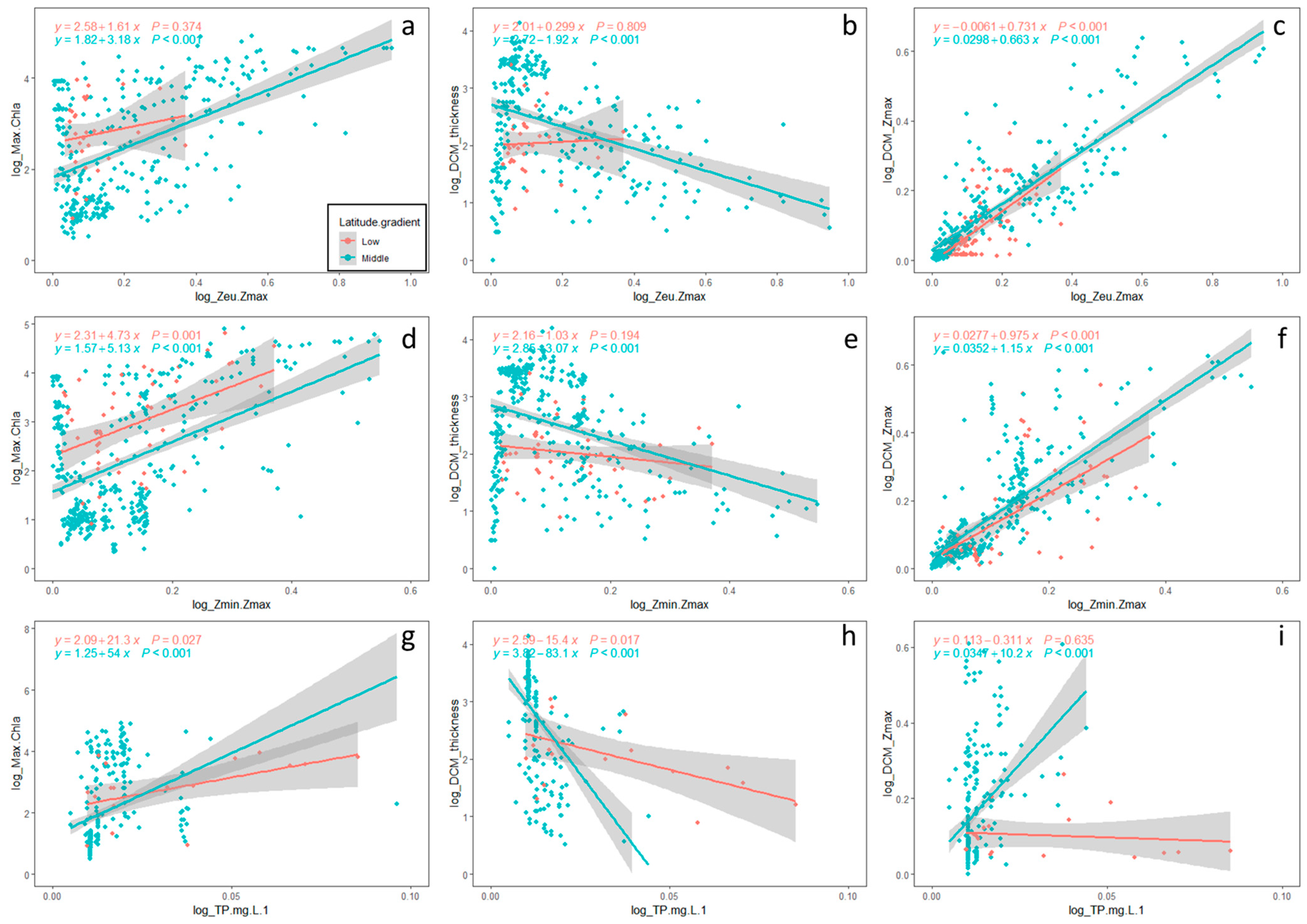

3.2. Relationships Between Environmental Variables and Deep Chlorophyll Maxima (DCM) Features

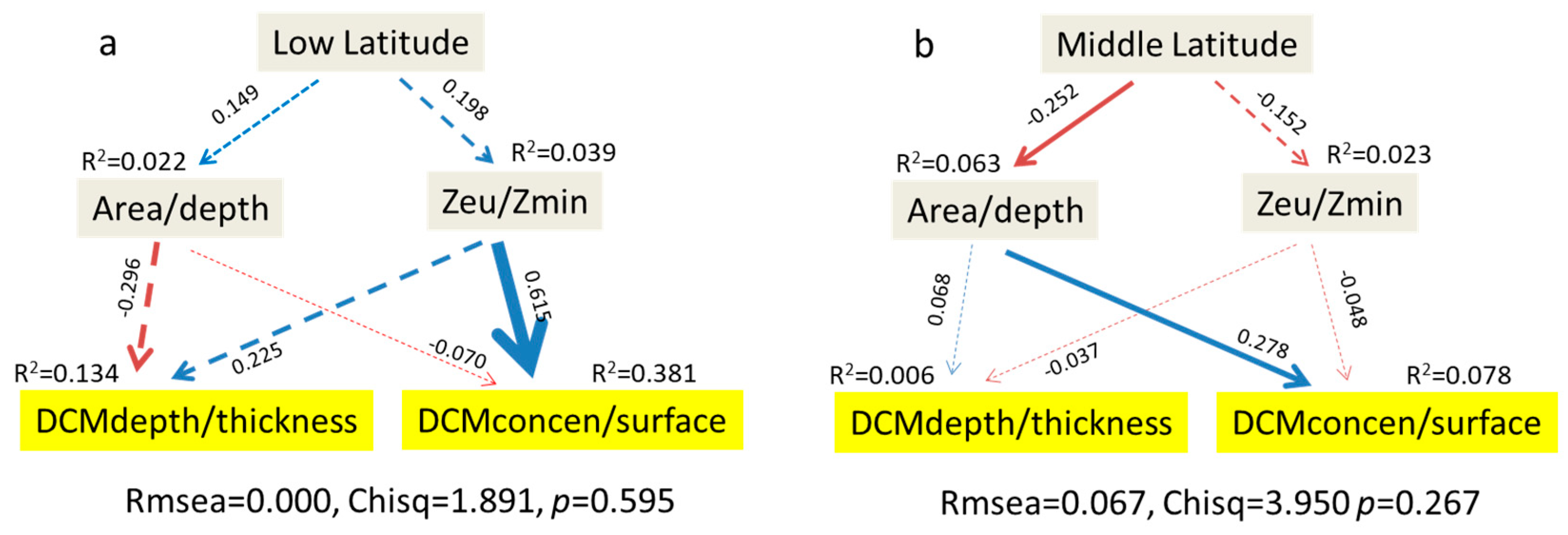

3.3. The Influence of Latitude on DCM Structures

4. Discussions

4.1. Strong TP–Chl a Relationship in Higher Latitude Lakes

4.2. Shallower and Thinner DCM Structures in Higher-Latitude Lakes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Yu, Z.; Song, D.; Jeppesen, E.; Zhou, Q. Patterns of thermocline structure and the deep chlorophyll maxima feature in multiple stratified lakes related to environmental drivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, T.H.; Beisner, B.E.; Carey, C.C.; Pernica, P.; Rose, K.C.; Huot, Y.; Brentrup, J.A.; Domaizon, I.; Grossart, H.P.; Ibelings, B.W.; et al. Patterns and drivers of deep chlorophyll maxima structure in 100 lakes: The relative importance of light and thermal stratification. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018, 63, 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, A.E.; Watkins, J.M.; Osantowski, E.; Rudstam, L.G. Deep chlorophyll maxima across a trophic state gradient: A case study in the Laurentian Great Lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2020, 65, 2460–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis, D.; Mantzouki, E.; McGinnis, D.F.; Vachon, D.; Gallego, I.; Grossart, P.; Domis, S.; Teurlincx, S.; Seelen, L.; Lürling, M.; et al. Stratification strength and light climate explain variation in chlorophyll a at the continental scale in a European multilake survey in a heatwave summer. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 4314–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, C. On the occurrence and ecological features of deep chlorophyll maxima (DCM) in Spanish stratified lakes. Limnetica 2006, 25, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, E.J.; Hecky, R.E.; Kasian, S.E.M.; Cruikshank, D.R. Effects of lake size, water clarity, and climatic variability on mixing depths in Canadian Shield lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1996, 41, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongve, D. Summer mixing depths in small lakes in Southeast Norway depend on surface area and water colour. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Und Angew. Limnol. Verhandlungen 2006, 29, 1935–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, B.M.; Anneville, O.; Chandra, S.; Dix, M.; Kuusisto, E.; Livingstone, D.M.; Rimmer, A.; Schladow, S.G.; Silow, E.; Sitoki, L.M.; et al. Morphometry and average temperature affect lake stratification responses to climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 4981–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.S.; Cavaletto, J.F.; Bootsma, H.A.; Lavrentyev, P.J.; Troncone, F. Nitrogen cycling rates and light effects in tropical Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998, 43, 1814–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, G.W. Comparative transparency, depth of mixing, and stability of stratification in lakes of Cameroon, West Africa 1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1988, 33, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillin, G.; Shatwell, T. Generalized scaling of seasonal thermal stratification in lakes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 161, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nõges, P.; Nõge, T.; Ghiani, M.; Paracchini, B.; Pinto Grande, J.; Sena, F. Morphometry and trophic state modify the thermal response of lakes to meteorological forcing. Hydrobiologia 2011, 667, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, M.R.; Wu, C.H. Responses of water temperature and stratification to changing climate in three lakes with different morphometry. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 6253–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhu, G.; Sun, X. Thermal structure controlled by morphometry and light attenuation across subtropical reservoirs. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36, e14502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patalas, K. Mid-summer mixing depths of lakes of different latitudes: With 5 figures in the text. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Und Angew. Limnol. Verhandlungen 1984, 22, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Beklioğlu, M.; Özkan, K.; Akyürek, Z. Salinization increase due to climate change will have substantial negative effects on inland waters: A call for multifaceted research at the local and global scale. Innovation 2020, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhu, R.; Zhou, Q.; Jeppesen, E.; Yang, K. Trophic status and lake depth play important roles in determining the nutrient-chlorophyll a relationship: Evidence from thousands of lakes globally. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, G.; Pietiläinen, O.P.; Carvalho, L.; Solimini, A.; Lyche Solheim, A.; Cardoso, A.C. Chlorophyll–nutrient relationships of different lake types using a large European dataset. Aquat. Ecol. 2008, 42, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, J.M.; Özkundakci, D.; Hamilton, D.P.; Jones, J.R. Latitudinal variation in nutrient stoichiometry and chlorophyll-nutrient relationships in lakes: A global study. Fundam. Appl. Limnol 2012, 181, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, D.; McCarthy, M.J.; Shatwell, T.; Borchardt, D.; Jeppesen, E.; Søndergaard, M.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Davidson, T.A. Consistent stoichiometric long-term relationships between nutrients and chlorophyll-a across lakes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehrer, B.; Schultze, M. Stratification of lakes. Rev. Geophys. 2008, 46, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briddon, C.L.; Metcalfe, S.; Taylor, D.; Bannister, W.; Cunanan, M.; Santos-Borja, A.C.; Papa, R.D.; McGowan, S. Changing water quality and thermocline depth along an aquaculture gradient in six tropical crater lakes. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmundson, J.A.; Mazumder, A. Regional and hierarchical perspectives of thermal regimes in subarctic, Alaskan lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, R.; Filazzola, A.; Mahdiyan, O.; Shuvo, A.; Blagrave, K.; Ewins, C.; Moslenko, L.; Gray, D.K.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S. Relationships of total phosphorus and chlorophyll in lakes worldwide. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.M., Jr. Basis for the protection and management of tropical lakes. Lakes Reserv. Res. Manag. 2000, 5, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, L.; Aura, C.M.; Becker, V.; Briddon, C.L.; Carvalho, L.R.; Dobel, A.J.; Jamwal, P.; Kamphuis, B.; Marinho, M.M.; McGowan, S.; et al. Getting into hot water: Water quality in tropical lakes in relation to their utilisation. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 789, p. 012021. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Soranno, P.A.; Wagner, T. The role of phosphorus and nitrogen on chlorophyll a: Evidence from hundreds of lakes. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepori, F.; Bartosiewicz, M.; Simona, M.; Veronesi, M. Effects of winter weather and mixing regime on the restoration of a deep perialpine lake (Lake Lugano, Switzerland and Italy). Hydrobiologia 2018, 824, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.P.; O’Brien, K.R.; Burford, M.A.; Brookes, J.D.; McBride, C.G. Vertical distributions of chlorophyll in deep, warm monomictic lakes. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 72, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Melack, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, G.; Wu, Z.; Liu, M. Spatial variations of subsurface chlorophyll maxima during thermal stratification in a large, deep subtropical reservoir. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2020, 125, e2019JG005480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhou, J.; Elser, J.J.; Gardner, W.S.; Deng, J.; Brookes, J.D. Water depth underpins the relative roles and fates of nitrogen and phosphorus in lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatwell, T.; Nicklisch, A.; Köhler, J. Temperature and photoperiod effects on phytoplankton growing under simulated mixed layer light fluctuations. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2012, 57, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low-Latitude Lakes (n = 18) | Middle-Latitude Lakes (n = 70) | U Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude (decimal degrees) | 26.6 (14.7–32.1) | 47.5 (42.1–54.1) | —— |

| Mean depth (m) | 33.5 (7.6–106.3) | 28.3 (2.3–169.0) | ns |

| Lake area (km2) | 59.9 (0.2–560.0) | 3522.7 (0.0–82,097) | ns |

| TN (mg/L) | 0.62 (0.04–2.12) | 0.33 (0.17–0.75) | *** |

| TP (mg/L) | 0.031 (0.001–0.089) | 0.016 (0.005–0.038) | *** |

| Surface Chl a (μg/L) | 2.3 (0.1–13.9) | 10.1 (0.1–27.1) | *** |

| Zeu/Zmax | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.5 (0.0–1.5) | *** |

| Zmin/Zmax | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | ** |

| DCM concentration (μg/L) | 22.7 (1.5–51.3) | 33.3 (1.8–109) | * |

| DCM/Zmax | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 1.1 (0.0–22.5) | ns |

| DCM thickness (m) | 8.6 (1.4–29.0) | 7.9 (0.7–29.3) | *** |

| Area/depth | 60.9 (0.0–1068.9) | 30.7 (0.00–726.4) | ns |

| Zeu/Zmin | 1.98 (0.33–5.18) | 2.51 (0.69–15.00) | ns |

| TN/TP | 20.92 (2.47–108.13) | 22.25 (13.33–102.00) | ns |

| DCMdepth/thickness | 1.56 (0.36–7.90) | 1.76 (0.06–7.00) | ns |

| DCM concentration/surface | 49.10 (0.70–446.52) | 3.72 (1.11–20.02) | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Ma, X. Climate Zones Modulate Deep Chlorophyll Maxima in Middle-Latitude Lakes via Thermocline Development. Diversity 2026, 18, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010046

Wang L, Zhou Q, Li Y, Ma X. Climate Zones Modulate Deep Chlorophyll Maxima in Middle-Latitude Lakes via Thermocline Development. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Li, Qichao Zhou, Yong Li, and Xufa Ma. 2026. "Climate Zones Modulate Deep Chlorophyll Maxima in Middle-Latitude Lakes via Thermocline Development" Diversity 18, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010046

APA StyleWang, L., Zhou, Q., Li, Y., & Ma, X. (2026). Climate Zones Modulate Deep Chlorophyll Maxima in Middle-Latitude Lakes via Thermocline Development. Diversity, 18(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010046