Unveiling Microalgal Diversity in Slovenian Transitional Waters (Adriatic Sea): A First Step Toward Ecological Status Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

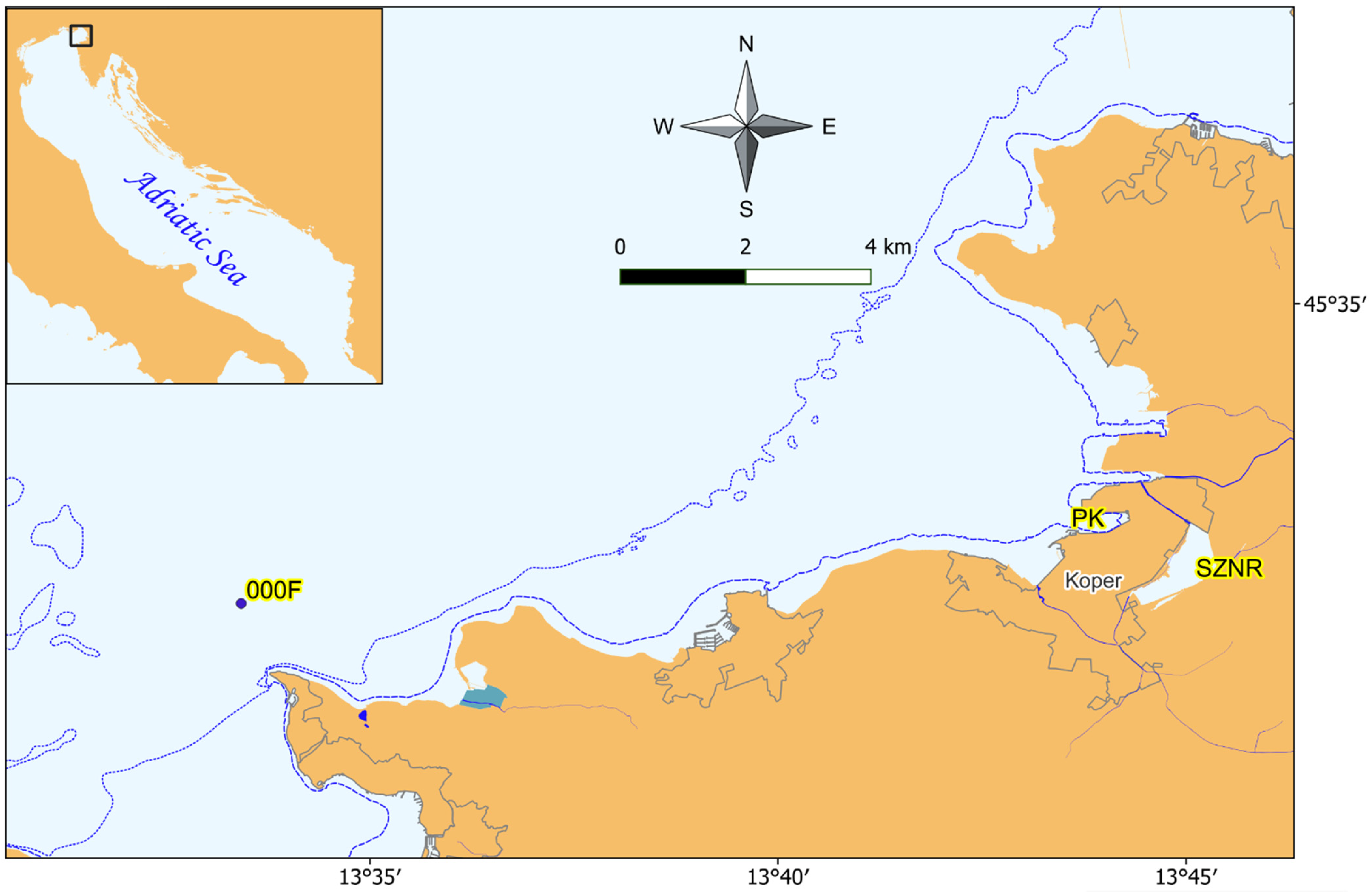

2.1. Description of the Study Area and Sampling Locations

2.2. Sampling and In Situ Measurements

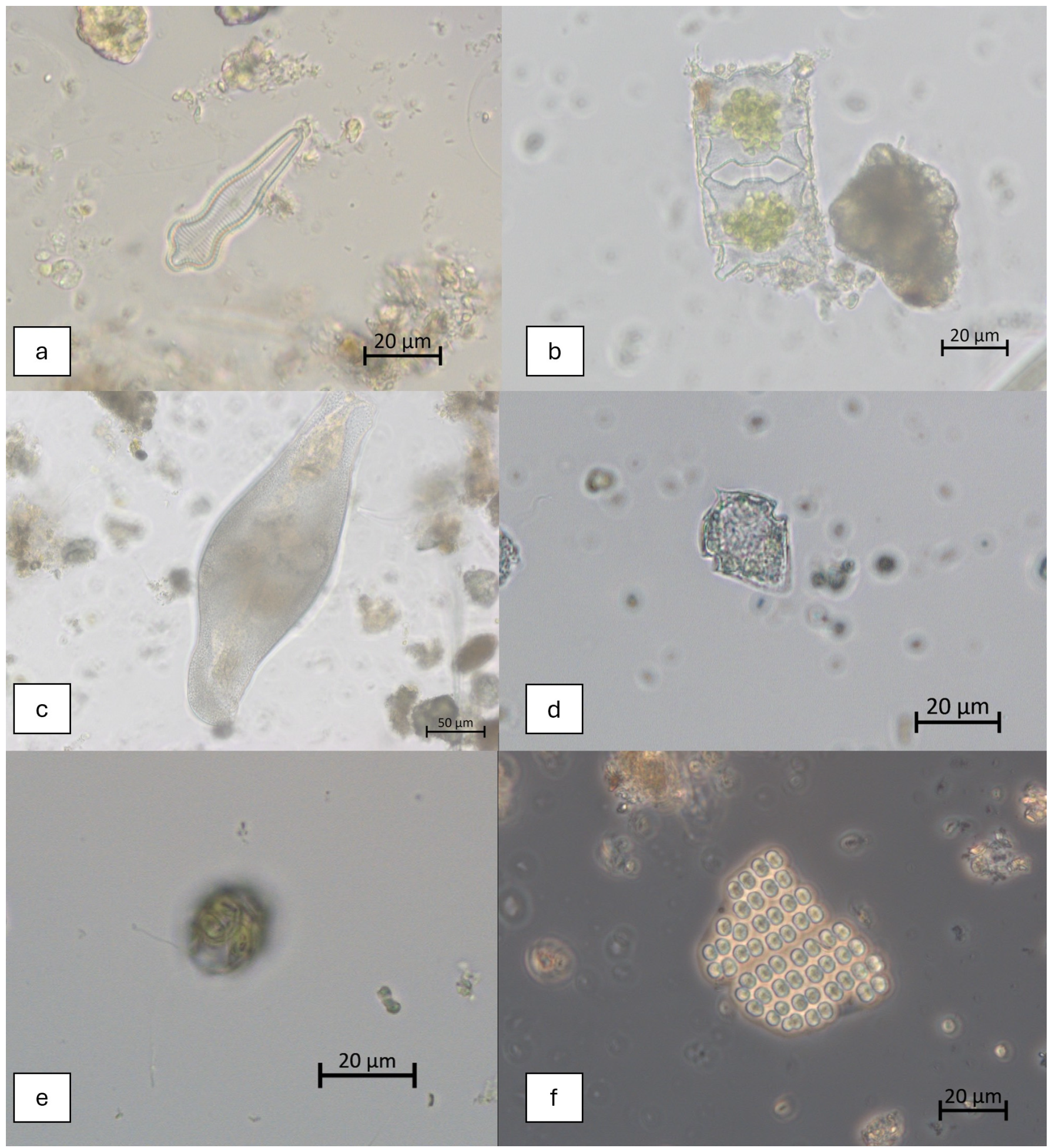

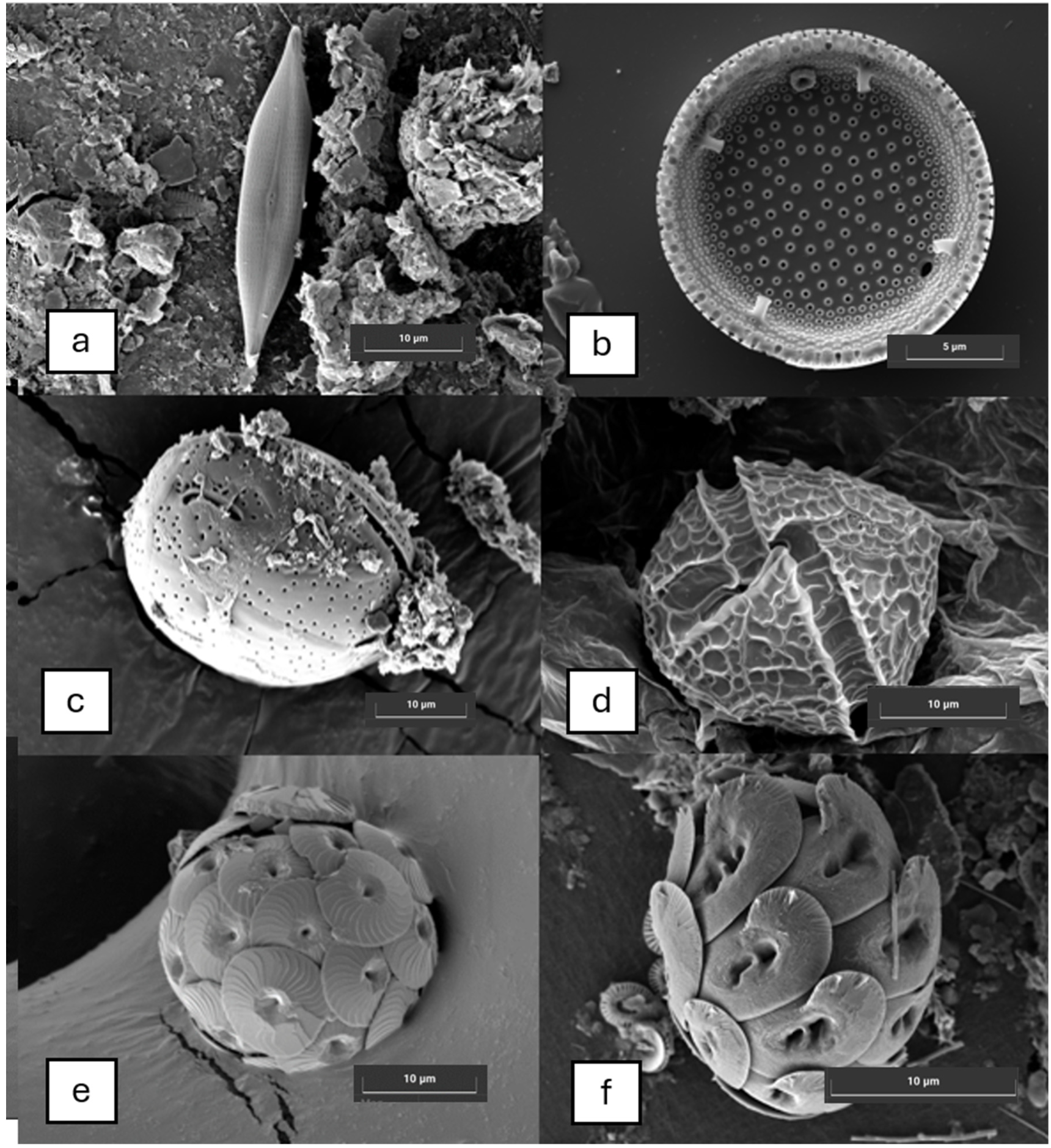

2.3. Microscopic Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Characteristics of Study Sites

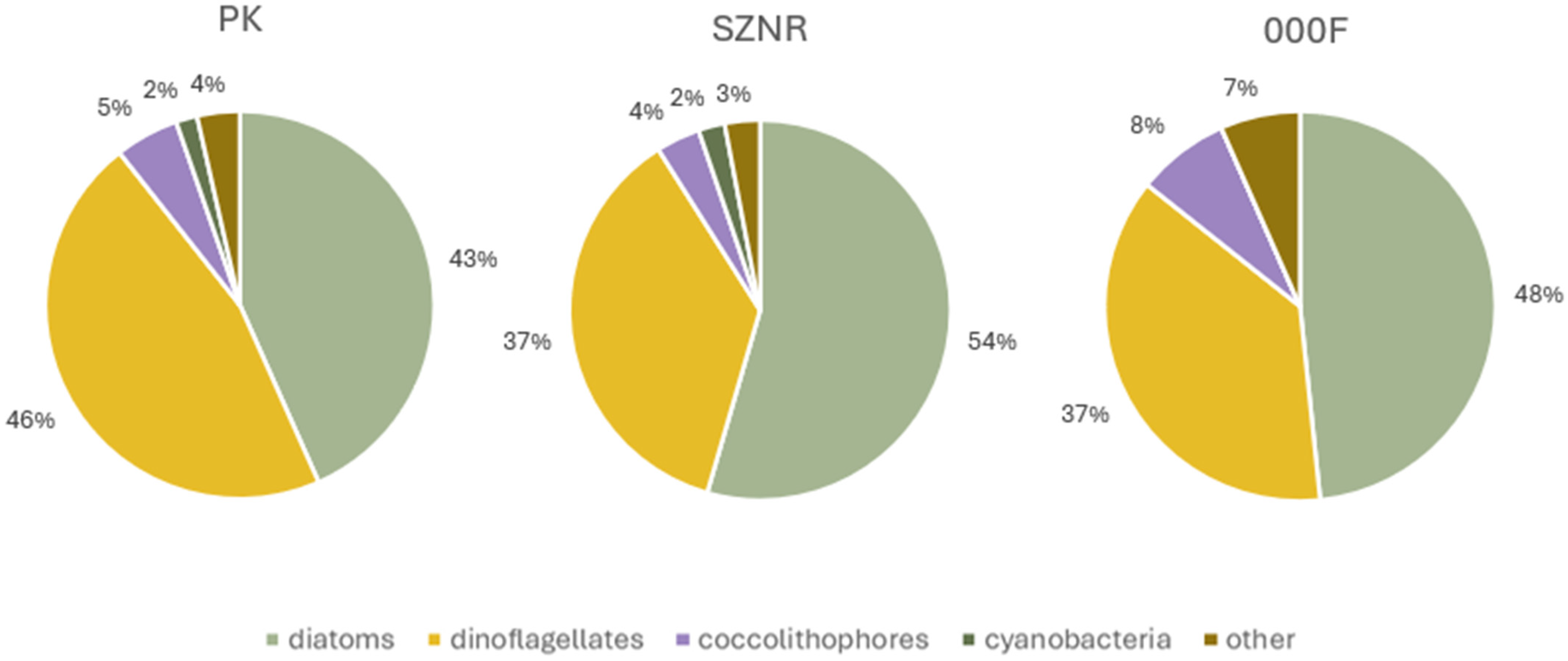

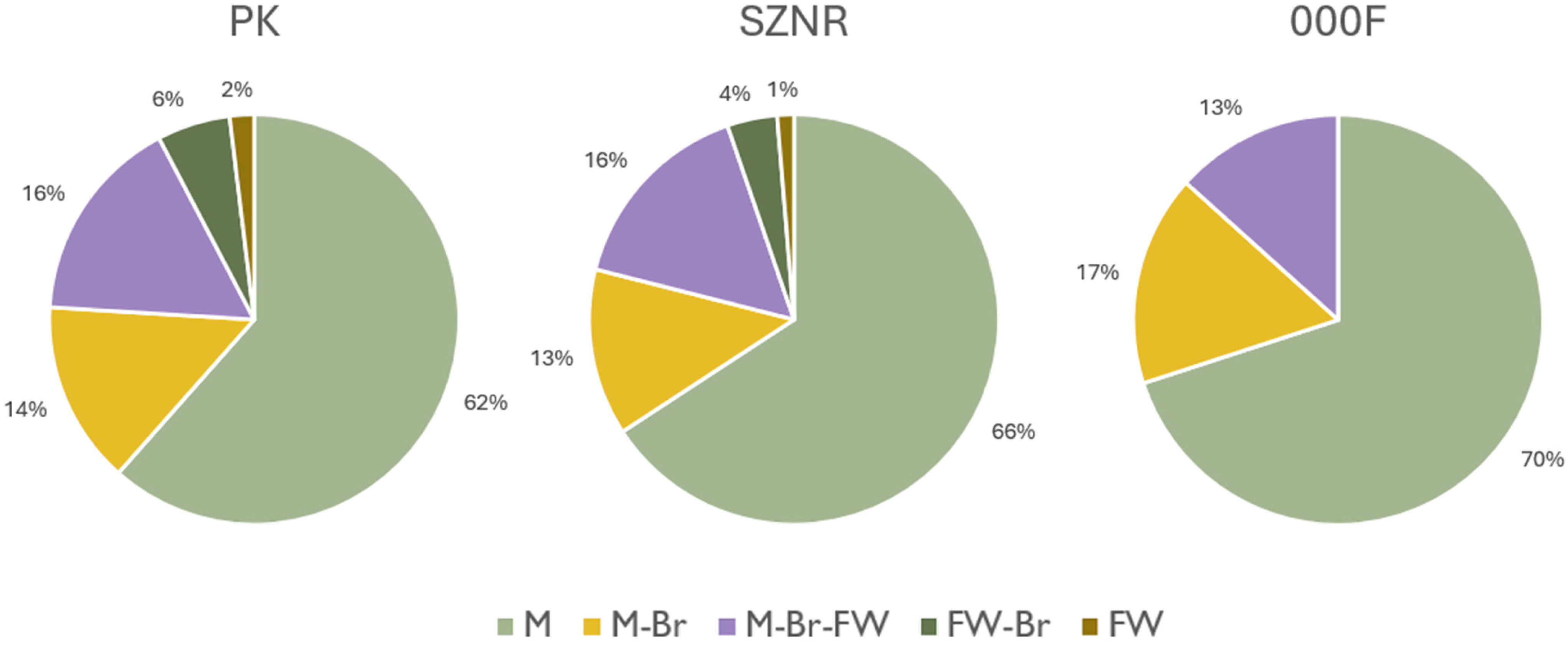

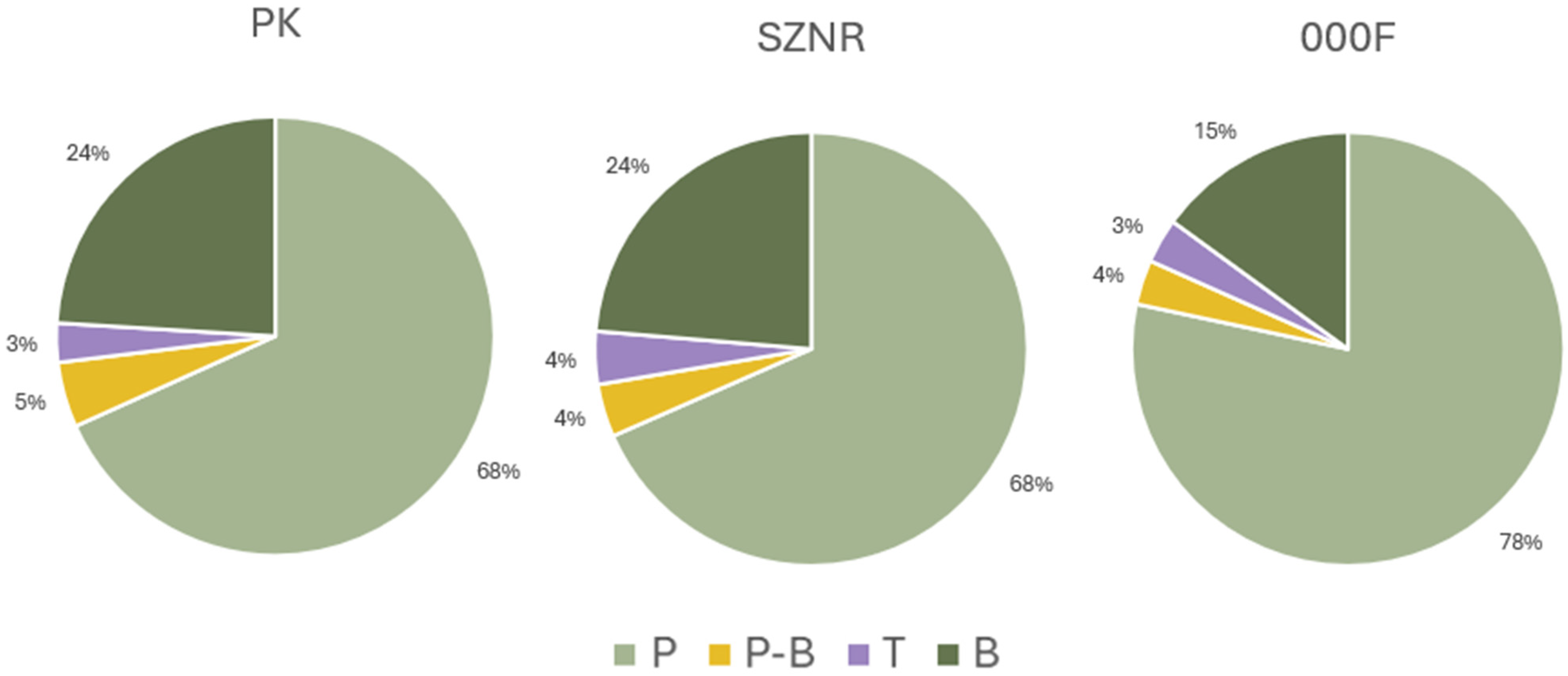

3.2. Diversity of Microalgae in Transitional Waters and Coastal Sea

3.3. First Recorded, NIS and HAB Species in Transitional Waters

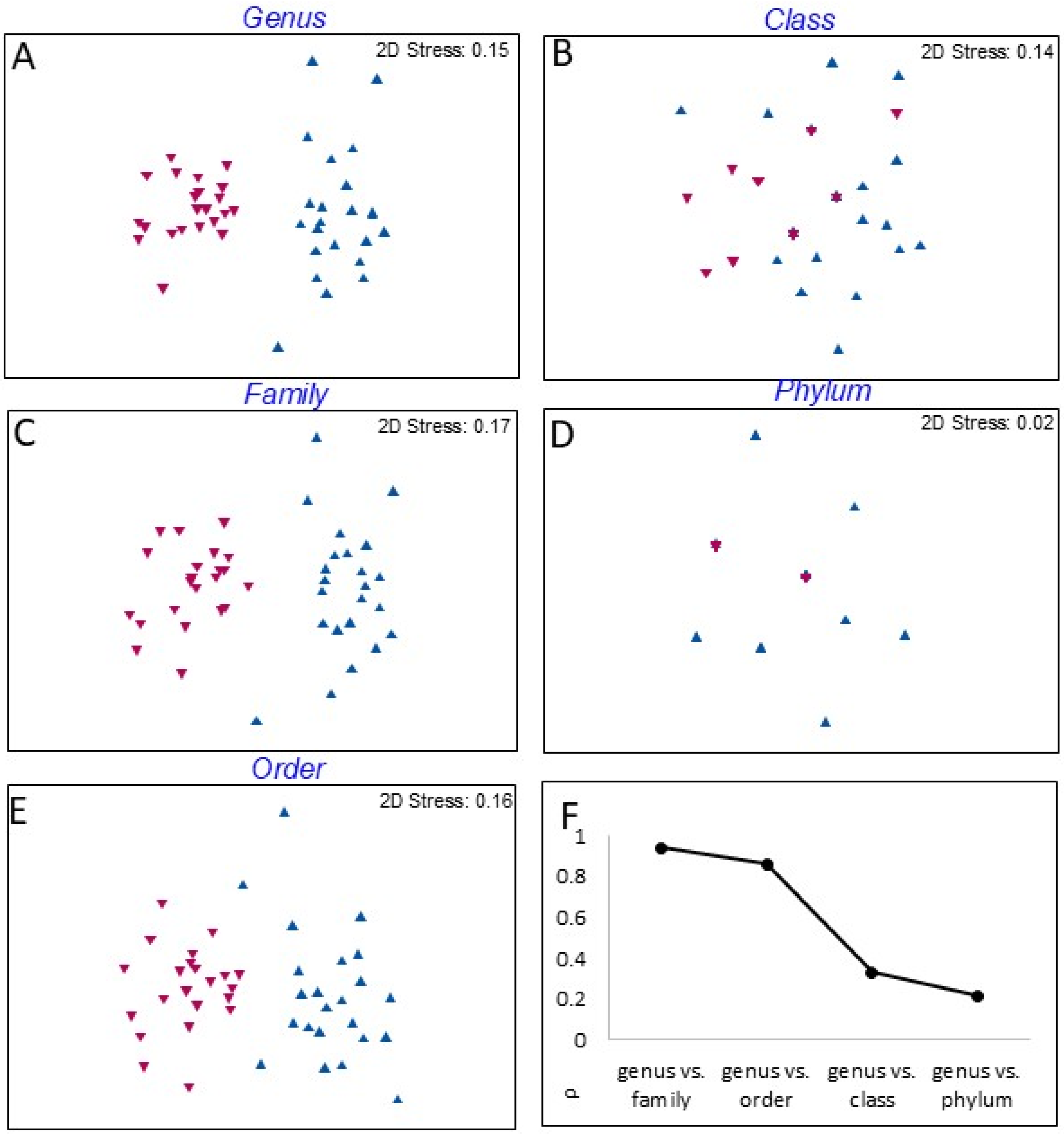

3.4. Comparison of Diversity Between Transitional and Coastal Marine Waters

4. Discussion

4.1. Microalgal Diversity and Ecological Gradients

4.2. HAB Taxa in Transitional Waters

4.3. Comparison with Coastal Marine Waters as a Framework for Monitoring in Transitional Waters

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennish, M.J. Environmental threats and environmental future of estuaries. Environ. Conserv. 2002, 29, 78–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Burdon, D.; Hemingway, K.L.; Apitz, S.E. Estuarine, coastal and marine ecosystem restoration: Confusing management and science—A revision of concepts. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2007, 74, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, L.B.; Nearhoof, J.E.; Tilton, C.L. Sediment grain size effect on benthic microalgal biomass in shallow aquatic ecosystems. Estuaries 1999, 22, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennish, M.J.; Haag, S.M.; Sakowicz, G.P. 8 Seagrass Decline in New Jersey Coastal Lagoons. In Coastal Lagoons: Critical Habitats of Environmental Change; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; p. 167. [Google Scholar]

- Facca, C.; Cavraro, F.; Franzoi, P.; Malavasi, S. Lagoon Resident Fish Species of Conservation Interest According to the Habitat Directive (92/43/CEE): A Review on Their Potential Use as Ecological Indicator Species. Water 2020, 12, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistri, M.; Albéri, M.; Chiarelli, E.; Cozzula, C.; Cunsolo, F.; Elek, N.I.; Mantovani, F.; Padoan, M.; Paletta, M.G.; Pezzi, M.; et al. Effects of Restoration Through Nature-Based Solution on Benthic Biodiversity: A Case Study in a Northern Adriatic Lagoon. Water 2025, 17, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, R.; Boutin, N. European LIFE Projects Dedicated to Ecological Restoration in Mediterranean and Black Sea Coastal Lagoons. Environments 2023, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Acri, F.; Alberighi, L.; Bastianini, M.; Boldrin, A.; Cavalloni, B.; Cioce, F.; Comaschi, A.; Rabitti, S.; Socal, G. Biological variability in the Venice Lagoon. In The Venice Lagoon Ecosystem: Inputs and Interactions Between Land and Sea; Man and the Biosphere Series; UNESCO: Paris, France; Parthenon Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 25, pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Aguzzi, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Bianchi, C.N.; Corbera, J.; Dailianis, T.; et al. The Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, Patterns, and Threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Marine Non-Indigenous Species in Europe’s Seas. 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/marine-non-indigenous-species-in?activeAccordion=ecdb3bcf-bbe9-4978-b5cf-0b136399d9f8 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Zenetos, A.; Çinar, M.E.; Crocetta, F.; Golani, D.; Rosso, A.; Servello, G.; Shenkar, N.; Turon, X.; Verlaque, M. Uncertainties and validation of alien species catalogues: The Mediterranean as an example. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 191, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outinen, O.; Bailey, S.A.; Casas-Monroy, O.; Delacroix, S.; Gorgula, S.; Griniene, E.; Kakkonen, J.E.; Srebaliene, G. Biological testing of ships’ ballast water indicates challenges for the implementation of the Ballast Water Management Convention. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1334286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailianis, T.; Akyol, O.; Babali, N.; Bariche, M.; Crocetta, F.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Chanem, R.; GÖKoĞLu, M.; Hasiotis, T.; Izquierdo-MuÑOz, A.; et al. New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (July 2016). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2016, 17, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E.; Fleming, L.E.; Gowen, R.; Davidson, K.; Hess, P.; Backer, L.C.; Moore, S.K.; Hoagland, P.; Enevoldsen, H. Marine harmful algal blooms, human health and wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 2015, 96, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroppo, C.; Pinna, M.; Vadrucci, M.R. Phytoplankton Size Structure and Diversity in the Transitional System of the Aquatina Lagoon (Southern Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean). Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roselli, L.; Stanca, E.; Ludovisi, A.; Durante, G.; Souza, J.; Dural, M.; Alp, T.; Gjoni, V.; Ghinis, S.; Basset, A. Multi-scale biodiverity patterns in phytoplankton from coastal lagoons: The Eastern Mediterranean. Transitional Waters Bull. 2013, 7, 202–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ligorini, V.; Malet, N.; Garrido, M.; Derolez, V.; Amand, M.; Bec, B.; Cecchi, P.; Pasqualini, V. Phytoplankton dynamics and bloom events in oligotrophic Mediterranean lagoons: Seasonal patterns but hazardous trends. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 2353–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanuko, N.; Valčić, M. Phytoplankton composition and biomass of the northern Adriatic lagoon of Stella Maris, Croatia. Acta Bot. Croat. 2009, 68, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanidou, N.; Katsiapi, M.; Tsianis, D.; Demertzioglou, M.; Michaloudi, E.; Moustaka-Gouni, M. Patterns in alpha and beta phytoplankton diversity along a conductivity gradient in coastal mediterranean lagoons. Diversity 2020, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minicante, S.A.; Piredda, R.; Finotto, S.; Aubry, F.B.; Acri, F.; Pugnetti, A.; Zingone, A. Spatial diversity of planktonic protists in the Lagoon of Venice (LTER-Italy) based on 18S rDNA. Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 2020, 11, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, P.; Jouenne, F.; Friedl, T.; Deton-Cabanillas, A.-F.; Le Roy, B.; Véron, B. Phytoplankton diversity and community composition along the estuarine gradient of a temperate macrotidal ecosystem: Combined morphological and molecular approaches. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigas, M.L.; Llebot, C.; Ross, O.N.; Neszi, N.Z.; Rodellas, V.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Masqué, P.; Piera, J.; Estrada, M.; Berdalet, E. Understanding the spatio-temporal variability of phytoplankton biomass distribution in a microtidal Mediterranean estuary. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2014, 101, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapov, J.; Bužančić, M.; Skejić, S.; Mandić, J.; Bakrač, A.; Straka, M.; Ninčević Gladan, Ž. Phytoplankton dynamics in the middle Adriatic estuary, with a focus on the potentially toxic genus pseudo-nitzschia. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boicourt, W.C.; Kuzmić, M.; Hopkins, T.S. The inland sea: Circulation of Chesapeake Bay and the Northern Adriatic. In Ecosystems at the Land-Sea Margin: Drainage Basin to Coastal Sea; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Volume 55, pp. 81–129. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, M.J.; Mozetič, P.; Francé, J.; Aubry, F.B.; Djakovac, T.; Faganeli, J.; Harris, L.A.; Niesen, M. Phytoplankton dynamics in a changing environment. In Coastal Ecosystems in Transition: A Comparative Analysis of the Northern Adriatic and Chesapeake Bay; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lipej, B.; Lipej, L.; Kerma, S. Škocjanski zatok Nature Reserve: A case study of a protected urban wetland area and tourist attraction. In Challenges of Tourism Development in Protected Areas of Croatia and Slovenia; Publishing House of the University of Primorska, Croatian Geographical Society: Koper, Slovenia, 2020; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, K.; Nielsen, T.S.; Aalbers, C.; Bell, S.; Boitier, B.; Chery, J.P.; Fertner, C.; Groschowski, M.; Haase, D.; Loibl, W. Strategies for sustainable urban development and urban-rural linkages. Eur. J. Spat. Dev. 2014, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantar, P. Geographical overview of water balance of Slovenia 1971–2000 by main river basins. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2007, 47, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, L.; Triemer, R.E. A rapid simple technique utilizing calcofluor white M2R for the visualization of dinoflagellate thecal plates 1. J. Phycol. 1985, 21, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobajo, R.; Mann, D.G. A rapid cleaning method for diatoms. Diatom Res. 2019, 34, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, J.D. Marine Dinoflagellates of the British Isles; Her Majesty’s Stationary Office: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tomas, C.R. Identifying Marine Phytoplankton; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, M.A.; Gulledge, R.A. Identifying Harmful Marine Dinoflagellates; Department of Systematic Biology-Botany: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Viličić, D. Fitoplankton Jadranskoga Mora—Biologija i Taksonomija; Školska knjiga: Zagreb, Hrvatska, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, G.; Raine, R. The Dinoflagellate Genus Ceratium in Irish Shelf Seas; The Martin Ryan Institute: Galway, Ireland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kraberg, A.; Baumann, M.; Dürselen, C.-D. Coastal Phytoplankton. Photo Guide for Northern European Seas; Verlag Friedrich Pfeil: München, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication. 2025. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. 2025. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Lundholm, N.; Churro, C.; Escalera, L.; Fraga, S.; Hoppenrath, M.; Iwataki, M.; Larsen, J.; Mertens, K.; Moestrup, Ø.; Murray, S. IOC-UNESCO Taxonomic Reference List of Harmful Micro Algae. 2009. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/hab (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Lassus, P.; Chaumérat, N.; Hess, P.; Nézan, E.; Reguera, B. Toxic and harmful microalgae of the World Ocean; International Society for the Study of Harmful Algae and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mozetič, P.; Cangini, M.; Francé, J.; Bastianini, M.; Aubry, F.B.; Bužančić, M.; Cabrini, M.; Cerino, F.; Čalić, M.; D’Adamo, R. Phytoplankton diversity in Adriatic ports: Lessons from the port baseline survey for the management of harmful algal species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 147, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Carneiro, F.; Bini, L.M.; Rodrigues, L.C. Influence of taxonomic and numerical resolution on the analysis of temporal changes in phytoplankton communities. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira-Flores, D.; Rubal, M.; Cabecinha, E.; Díaz-Agras, G.; Gomes, P.T. Unveiling the role of taxonomic sufficiency for enhanced ecosystem monitoring. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 200, 106631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfriso, A.; Facca, C.; Bonometto, A.; Boscolo, R. Compliance of the macrophyte quality index (MaQI) with the WFD (2000/60/EC) and ecological status assessment in transitional areas: The Venice lagoon as study case. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 46, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, E.; Radaelli, M.; Corami, F.; Turetta, C.; Toscano, G.; Capodaglio, G. Temporal evolution of cadmium, copper and lead concentration in the Venice Lagoon water in relation with the speciation and dissolved/particulate partition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerino, F.; Fornasaro, D.; Kralj, M.; Giani, M.; Cabrini, M. Phytoplankton temporal dynamics in the coastal waters of the north-eastern Adriatic Sea (Mediterranean Sea) from 2010 to 2017. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 34, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascotto, I.; Mozetič, P.; Francé, J. Phytoplankton time-series in a LTER site of the Adriatic Sea: Methodological approach to decipher community structure and indicative taxa. Water 2021, 13, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orel, N.; Fadeev, E.; Klun, K.; Ličer, M.; Tinta, T.; Turk, V. Bacterial indicators are ubiquitous members of pelagic microbiome in anthropogenically impacted coastal ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 765091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roselli, L.; Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Goela, P.C.; Cristina, S.; Rieradevall, M.; D’adamo, R.; Newton, A. Do physiography and hydrology determine the physico-chemical properties and trophic status of coastal lagoons? A comparative approach. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 117, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.C.; Newton, A.; Fernandes, T.F.; Tett, P. The role of microphytobenthos on shallow coastal lagoons: A modelling approach. Biogeochemistry 2011, 106, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, R.; Ninčević-Gladan, Ž.; Auriemma, R.; Bastianini, M.; Bolognini, L.; Cabrini, M.; Cara, M.; Čalić, M.; Campanelli, A.; Cvitković, I.; et al. Strategy of port baseline surveys (PBS) in the Adriatic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 147, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinta, T.; Vojvoda, J.; Mozetič, P.; Talaber, I.; Vodopivec, M.; Malfatti, F.; Turk, V. Bacterial community shift is induced by dynamic environmental parameters in a changing coastal ecosystem (northern Adriatic, northeastern Mediterranean Sea)--a 2-year time-series study. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 3581–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flander-Putrle, V.; Francé, J.; Mozetič, P. Phytoplankton Pigments Reveal Size Structure and Interannual Variability of the Coastal Phytoplankton Community (Adriatic Sea). Water 2022, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, M.A. Three new benthic species of Prorocentrum (Dinophyceae) from Twin Cays, Belize: P. maculosum sp. nov., P. foraminosum sp. nov. and P. formosum sp. nov. Phycologia 1993, 32, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Tsiamis, K.; Galanidi, M.; Carvalho, N.; Bartilotti, C.; Canning-Clode, J.; Castriota, L.; Chainho, P.; Comas-González, R.; Costa, A.C.; et al. Status and Trends in the Rate of Introduction of Marine Non-Indigenous Species in European Seas. Diversity 2022, 14, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, A.; Licandro, P.; Sarno, D. Revising paradigms and myths of phytoplankton ecology using biological time series. In Mediterranean Biological Time Series; Briand, F., Ed.; CIESM Workshop Monographs N° 22; CIESM Publisher: Monaco, Monaco, 2003; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zingone, A.; Escalera, L.; Aligizaki, K.; Fernández-Tejedor, M.; Ismael, A.; Montresor, M.; Mozetič, P.; Taş, S.; Totti, C. Toxic marine microalgae and noxious blooms in the Mediterranean Sea: A contribution to the Global HAB Status Report. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk Dermastia, T.; Cerino, F.; Stanković, D.; Francé, J.; Ramšak, A.; Žnidarič Tušek, M.; Beran, A.; Natali, V.; Cabrini, M.; Mozetič, P. Ecological time series and integrative taxonomy unveil seasonality and diversity of the toxic diatom Pseudo-nitzschia H. Peragallo in the northern Adriatic Sea. Harmful Algae 2020, 93, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrini, M.; Cerino, F.; de Olazabal, A.; Di Poi, E.; Fabbro, C.; Fornasaro, D.; Goruppi, A.; Flander-Putrle, V.; Francé, J.; Gollasch, S.; et al. Potential transfer of aquatic organisms via ballast water with a particular focus on harmful and non-indigenous species: A survey from Adriatic ports. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 147, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henigman, U.; Mozetič, P.; Francé, J.; Knific, T.; Vadnjal, S.; Dolenc, J.; Kirbiš, A.; Biasizzo, M. Okadaic acid as a major problem for the seafood safety (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and the dynamics of toxic phytoplankton in the Slovenian coastal sea (Gulf of Trieste, Adriatic Sea). Harmful Algae 2024, 135, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aligizaki, K.; Nikolaidis, G. The presence of the potentially toxic genera Ostreopsis and Coolia (Dinophyceae) in the North Aegean Sea, Greece. Harmful Algae 2006, 5, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Gharbia, H.; Laabir, M.; Ben Mhamed, A.; Gueroun, S.K.M.; Daly Yahia, M.N.; Nouri, H.; M’Rabet, C.; Shili, A.; Kéfi-Daly Yahia, O. Occurrence of epibenthic dinoflagellates in relation to biotic substrates and to environmental factors in Southern Mediterranean (Bizerte Bay and Lagoon, Tunisia): An emphasis on the harmful Ostreopsis spp., Prorocentrum lima and Coolia monotis. Harmful Algae 2019, 90, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninčević Gladan, Ž.; Arapov, J.; Casabianca, S.; Penna, A.; Honsell, G.; Brovedani, V.; Pelin, M.; Tartaglione, L.; Sosa, S.; Dell’Aversano, C.; et al. Massive Occurrence of the Harmful Benthic Dinoflagellate Ostreopsis cf. ovata in the Eastern Adriatic Sea. Toxins 2019, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, A.; Vila, M.; Fraga, S.; Giacobbe, M.G.; Andreoni, F.; Riobó, P.; Vernesi, C. Characterization of Ostreopsis and Coolia (Dinophyceae) Isolates in the Western Mediterranean Sea Based on Morphology, Toxicity and Internal Transcribed Spacer 5.8S rDNA Sequences. J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciminiello, P.; Dell’Aversano, C.; Fattorusso, E.; Forino, M.; Magno, G.S.; Tartaglione, L.; Grillo, C.; Melchiorre, N. The Genoa 2005 outbreak. Determination of putative palytoxin in Mediterranean Ostreopsis o vata by a new liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 6153–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrini, M.; Fornasaro, D.; Lipizer, M.; Guardiani, B. First report of Ostreopsis cf. ovata bloom in the Gulf of Trieste. Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 2010, 17, 366–367. [Google Scholar]

- Keliri, E.; Paraskeva, C.; Sofokleous, A.; Sukenik, A.; Dziga, D.; Chernova, E.; Brient, L.; Antoniou, M.G. Occurrence of a single-species cyanobacterial bloom in a lake in Cyprus: Monitoring and treatment with hydrogen peroxide-releasing granules. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.R.; Vasconcelos, V.M. Planktonic and benthic cyanobacteria of European brackish waters: A perspective on estuaries and brackish seas. Eur. J. Phycol. 2011, 46, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, B.; Kosi, G. Harmful cyanobacterial blooms in Slovenia-bloom types and microcystin producers. Acta Biol. Slov. 2002, 45, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupančič, M.; Kogovšek, P.; Šter, T.; Remec Rekar, Š.; Cerasino, L.; Baebler, Š.; Krivograd Klemenčič, A.; Eleršek, T. Potentially toxic planktic and benthic cyanobacteria in Slovenian freshwater bodies: Detection by quantitative PCR. Toxins 2021, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessup, D.A.; Miller, M.A.; Ryan, J.P.; Nevins, H.M.; Kerkering, H.A.; Mekebri, A.; Crane, D.B.; Johnson, T.A.; Kudela, R.M. Mass Stranding of Marine Birds Caused by a Surfactant-Producing Red Tide. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Parrish, J.K.; Punt, A.E.; Trainer, V.L.; Kudela, R.; Lang, J.; Brancato, M.S.; Odell, A.; Hickey, B. Mass mortality of marine birds in the Northeast Pacific caused by Akashiwo sanguinea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 579, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk Dermastia, T.; Dall’Ara, S.; Dolenc, J.; Mozetič, P. Toxicity of the Diatom Genus Pseudo-nitzschia (Bacillariophyceae): Insights from Toxicity Tests and Genetic Screening in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Toxins 2022, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facca, C.; Bernardi Aubry, F.; Socal, G.; Ponis, E.; Acri, F.; Bianchi, F.; Giovanardi, F.; Sfriso, A. Description of a Multimetric Phytoplankton Index (MPI) for the assessment of transitional waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 79, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, D.; Borja, A.; Jones, J.I.; Pont, D.; Boets, P.; Bouchez, A.; Bruce, K.; Drakare, S.; Hänfling, B.; Kahlert, M.; et al. Implementation options for DNA-based identification into ecological status assessment under the European Water Framework Directive. Wat. Res. 2018, 138, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, F.; Ubaldi, M.; Accoroni, S.; Ricci, S.; Banchic, E.; Romagnoli, T.; Totti, C. Comparative analysis of phytoplankton diversity using microscopy and metabarcoding: Insights from an eLTER station in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Hydrobiologia 2025, 852, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi Aubry, F.; Acri, F.; Finotto, S.; Pugnetti, A. Phytoplankton dynamics and water quality in the Venice lagoon. Water 2021, 13, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Site | Period | T (°C) | Salinity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | ||

| SZNR * | 2018–2020 | 0.2 | 32.2 | 14.7 ± 7.7 | 1.9 | 35.9 | 21.6 ± 9.6 |

| PK | August 2020–May 2021 | 9.4 | 25.4 | 14.2 ± 4.8 | 12.0 | 36.5 | 24.3 ± 10.2 |

| 000F | April 2018–May 2021 | 9.79 | 26.92 | 17.65 ± 5.82 | 29.68 | 38.42 | 36.96 ± 1.56 |

| First Record | NIS/Cryptogenic | HAB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | PK | SZNR | PK | SZNR | PK | SZNR |

| DIATOMS | ||||||

| Actinocyclus sp. | + | + | ||||

| Asteromphalus cf. parvulus | + | |||||

| Chaetoceros cf. subtilis | + | + | ||||

| Cocconeis cf. sawensis | + | |||||

| Corethron sp. | + | |||||

| cf. Craticula cuspidata | + | |||||

| Cymbella sp. | + | + | ||||

| cf. Diatoma vulgaris | + | |||||

| Eupyxidicula turris | + | |||||

| Gomphonema cf. acuminatum | + | |||||

| Gyrosigma cf. fasciola | + | + | ||||

| Navicula cf. subrostellata | + | |||||

| Nitzschia cf. sigmoidea | + | |||||

| Odontella aurita | + | |||||

| Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata | + | + | ||||

| Pseudo-nitzschia spp. | (+) | (+) | ||||

| Tryblionella sp. | + | |||||

| DINOFLAGELLATES | ||||||

| Akashiwo sanguinea | + | + | ||||

| Alexandrium insuetum | + | + | ||||

| Alexandrium minutum | + | |||||

| Alexandrium cf. tamarense | + | |||||

| Alexandrium pseudogonyaulax | + | + | ||||

| Alexandrium spp. | (+) | (+) | ||||

| Azadinium caudatum var. margalefii | + | + | ||||

| Blixaea quinquecornis | + | |||||

| Coolia monotis | + | + | ||||

| Dinophysis acuminata | + | |||||

| Dinophysis caudata | + | + | ||||

| Dinophysis fortii | + | + | ||||

| Dinophysis ovum | + | |||||

| Dinophysis sacculus | + | + | ||||

| Dinophysis spp. | (+) | |||||

| Dinophysis tripos | + | |||||

| Gonyaulax polygramma | + | + | ||||

| Gonyaulax spinifera | + | + | ||||

| Gymnodinium cf. fuscum | + | |||||

| Heterocapsa spp. | (+) | (+) | ||||

| Lingulaulax polyedra | + | + | ||||

| Pentapharsodinium cf. dalei | + | |||||

| Phalacroma mitra | + | |||||

| Phalacroma rotundatum | + | + | ||||

| Prorocentrum cf. formosum | + | (?) | ||||

| Prorocentrum lima | + | + | ||||

| Protoceratium reticulatum | + | + | ||||

| Scaphodinium mirabile | + | + | ||||

| Tripos teres | + | |||||

| COCCOLITHOPHORES | ||||||

| Calcidiscus leptoporus | + | |||||

| Helicosphaera carteri | + | |||||

| CHLOROPHYTA | ||||||

| Pediastrum sp. | + | |||||

| Scenedesmus sp. | + | + | ||||

| CYANOBACTERIA | ||||||

| cf. Anabaena sp. | + | (+) | ||||

| Lyngbya sp. | + | + | (+) | (+) | ||

| Nostoc sp. | + | (+) | ||||

| Merismopedia sp. | + | + | (+) | (+) | ||

| Oscillatoria sp. | + | (+) | ||||

| Level | PERMANOVA | PERMDISP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pseudo-F | p (perm) | F | p (perm) | |

| genus | 26.51 | 0.0001 | 14.56 | 0.0009 |

| family | 26.53 | 0.0001 | 7.18 | 0.0123 |

| order | 27.75 | 0.0001 | 3.33 | 0.1005 |

| class | 4.91 | 0.0078 | 5.0557 | 0.0322 |

| phylum | 1.99 | 0.1577 | 11.375 | 0.0057 |

| Order | FO PK | FO 000F | Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isochrysidales | 0.26 | 1.00 | 5.40 |

| Stephanodiscales | 0.17 | 0.86 | 5.21 |

| Dinophysales | 1.00 | 0.27 | 5.16 |

| Lithodesmiales | 0.83 | 0.14 | 5.01 |

| Thalassiophysales | 0.04 | 0.73 | 4.88 |

| Licmophorales | 0.78 | 0.14 | 4.76 |

| Surirellales | 0.70 | 0.00 | 4.62 |

| Achnanthales | 0.70 | 0.14 | 4.30 |

| Paraliales | 0.78 | 0.32 | 4.18 |

| Melosirales | 0.61 | 0.00 | 4.05 |

| Mischococcales | 0.35 | 0.59 | 3.72 |

| Dictyochales | 0.74 | 0.45 | 3.62 |

| Thoracosphaerales | 0.48 | 0.55 | 3.52 |

| Probosciales | 0.87 | 0.55 | 3.35 |

| Striatellales | 0.52 | 0.00 | 3.35 |

| Asterolamprales | 0.39 | 0.14 | 2.83 |

| Gymnodiniales | 0.61 | 1.00 | 2.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Slavinec, P.; Francé, J.; Fortič, A.; Mozetič, P. Unveiling Microalgal Diversity in Slovenian Transitional Waters (Adriatic Sea): A First Step Toward Ecological Status Assessment. Diversity 2026, 18, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010021

Slavinec P, Francé J, Fortič A, Mozetič P. Unveiling Microalgal Diversity in Slovenian Transitional Waters (Adriatic Sea): A First Step Toward Ecological Status Assessment. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlavinec, Petra, Janja Francé, Ana Fortič, and Patricija Mozetič. 2026. "Unveiling Microalgal Diversity in Slovenian Transitional Waters (Adriatic Sea): A First Step Toward Ecological Status Assessment" Diversity 18, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010021

APA StyleSlavinec, P., Francé, J., Fortič, A., & Mozetič, P. (2026). Unveiling Microalgal Diversity in Slovenian Transitional Waters (Adriatic Sea): A First Step Toward Ecological Status Assessment. Diversity, 18(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010021