1. Introduction

The protection of human diversity is often considered distinct from the protection of biodiversity, despite recurring calls to revisit that divide and to understand culture as part of nature, or as an expression of it, for instance, under the concept of biocultural diversity [

1]. A growing detachment of the understanding of human societies from their natural history, opposing nature and culture, contributes to such a conception and contributes to the difficulties of cultural diversity protection. On occasion, such protection may tend to be conceived as safeguarding primarily “ancient traditions” rather than “the right to transformation”, i.e., segregating cultures by essentializing their cultural past phenomenological performance, as opposed to envisioning it as the varied expression of human adaptive and transformative characteristics [

2].

In the history of philosophical reasoning, such dichotomy was recurrent, echoing an anthropocentric reading of the environment, itself paying tribute to older ethnocentric divides. For instance, although he clearly embedded human behavior in the environment, Imanuel Kant wrote in his Geography [

3] that the world is the stage of human performance, thus separating the two.

However, the foundations of the modern philosophy of science recognize humans as part of nature and human thought as the self-awareness of nature itself, thus overcoming the divide [

4,

5,

6]. Even though the notion of nature has been approached from many different perspectives, [

7] the study of the divided notions of nature and culture is, to start with, a study of human performance, i.e., human behavioral transformations over time, within a given perceived space, i.e., a landscape.

The notion of landscape, in fact, allows humankind to be returned to nature, a merger based on the only perspective that humans can have: their own human perception. In this sense, the notion of landscape is of major relevance for any consideration of human diversity preservation.

In 1866, Élisée Reclus [

8] reflected on the sense of nature in modern societies, primarily those animated by artists, scientists, and travelers. He argued that the growing concentration of people and the economy in cities triggered a similarly growing interest in non-urban spaces, namely, mountainous areas. In his view, mountains, which had been central to life for agrarian societies since early times, became the focus of attention again for the dwellers of those big cities, who saw in them a refuge from the pressure, pollution, and stress of urban spaces. He also drew attention to the importance of sight in the process, considering that the view from the hills offered large horizons to contemplate and allowed one to acquire a sense of liberty, as opposed to the narrow confinements of the city.

It is clear that the “nature” portrayed by Redus was inherited from prior pastoral and farming societies, blended with forests, but within a kind of “tamed”, friendly scenario—what we may call a landscape.

As George Simmel argued a few years later [

9], humans perform in landscapes, i.e., in spatially delimited units that are anchored in the materiality of nature, a totality without spatial or chronological boundaries. Despite such material bases, he also considered that nature is “reconstructed by Man’s sight, that divides it and isolates it into distinct units”. In such sense, he wrote that nature would have an internal quality that sets the artificial, i.e., the anthropic, aside (or vice versa).

The approaches of Redus and Simmel, by the end of the 19th century, emerged from an epistemological framework dominated by naturalism and evolutionary theory, within which culture change was perceived as part of the natural history of human evolution. They were building from observed materialities (including economic transactions) and reflected on how humans perceived them, namely the importance of sight. This reflection was influenced by the technological advances in the domain of photography, which rendered evident the relevance of perceptions and senses, as pointed out by Walter Benjamin [

10]. Nature, in that sense, was perceived as a social construct forged through time.

In such an understanding of nature, besides the “tamed” blended landscape, there is also a sense of divide between what we can call the wild space (the undomesticated, the jungle, the domain of the infinite, monsters, and serendipity—or chaos, as in ancient Greece [

11], or Hundun in China [

12]) and the domestic space (the anthropic space as a place, the city, the means of communication, the domain of the frontiers, identities, and intentional causality).

The dichotomy seems so sharp that attempts were made to identify the underlying clear-cut mechanism, from early literary and religious texts (e.g., Adam and the apple, in the biblical traditions) to last-century scholarly research (e.g., the prohibition of incest, as such identified by Lévi-Strauss) [

13]. The process of the disclosure of nature, however, precludes its continuity: once understood by culture, or science, it becomes part of anthropic intelligibility, thus being no longer the domain of wilderness and falling within the scope of physics in the Aristotelian but also Einsteinian sense [

14].

Hence, the notion of nature resonates as a perceived non-human-driven reality, which can be subject to a commonly established set of descriptive criteria that may be shared and lead to the same common portrait; it is then no longer nature but a cultural landscape. Such a notion of a separate, non-human reality is itself a cultural construct, emerging from increasingly complex societies and their internal divisions. In many traditional societies, humans are perceived not as dominating or being subject to nature, but as part of it.

A step towards a divide between nature and culture is also to be found in communities that, while perceiving humans as part of the whole of nature, consider themselves to have specific responsibilities in the curation of biodiversity. Indeed, such an assumption implicates a detachment from nature and a capacity to observe it from the “outside”. For instance, the Kogi, an Indigenous community from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia, perceive the Earth as a living entity and that humans are the children of a mother goddess who is harmed by resource overexploitation. This perception leads the Kogi to take on the responsibility to preserve harmony against those threats.

The central performative and material process to preserve harmony is to weave, a practice that illustrates the notion of the creation of balance through the hands of humans. The Kogi’s cosmology, which shares a dualistic structure with many other traditional societies, as it has been understood for a long time [

15], binds together the divides through weaving, i.e., through human agency, thus integrating the natural expressions of the mother goddess creations (“nature”) and the other human’s overexploitation of resources within a common agency framework; this generates a global understanding that can be human-driven [

16], which is very close to the notion of a landscape.

The notion of landscape, which emerges at the dawn of modernity and major related human-induced land transformations, encapsulates the awareness of the progressive domestication of the wilderness, building a new kind of scenario in which the main agent is the human, who conditions other species’ patterns of behavior [

17]. This is very clear in European landscape paintings from the 17th century in Europe [

18], but also in earlier Chinese landscapes [

19] and, beyond that, from the dawn of prehistoric art [

20]. A symmetrical focus on wilderness landscapes would emerge, however, from the 18th and the romantic 19th century onwards, as a result of a perception of the loss of pristine scenarios due to the advances of modern farming and industry. However, such “natural” landscapes are not so much portraits of untamed territories, but representations of ideals of a re-encounter with nature. This will ultimately feed environmental preservation concerns and initiatives like establishing biosphere reserves, in any case being human constructs and, therefore, a “tamed nature” or a cultural landscape [

21].

The contemporary unclear conceptualization of landscape relates to its diverse origin: an anthropic transformation of the territory, generating a blend between the two (as in the German “landschaff”); an ideal representation of an area (as in the English “landscape”, or perceived “land area”); or a delimited area in the countryside (as in the French “paysage”, or perception of an inhabited portion of land).

In all of these definitions, which even today do not mean the same “thing” [

22], nature is replaced with an extended scenario of interaction of human agency. In this sense, the emergence of “landscapes” represents the awareness of the growing anthropization of the planet, regardless of whether the adopted perspective is that of its internal mechanisms (in German), its topographical delimitation (in French), or its sensory perception (in English).

Questioning the divides between culture and nature means addressing how such behavior changes through time and whether we are fundamentally different from, or similar to, our predecessors in different moments of the past. This, in the end, means to frame the scales of possible transformations from the present into the future: will our descendants be fundamentally different from, or similar to, us?

In this article, we revisit the core concepts of nature and landscape assessment and sustainability, based on which we propose an approach to natural resource management and diversity preservation from the perspective of cultural landscapes. We use Ingold’s anthropological concept of taskscape as a lever to integrate the so-called natural phenomena into the range of human-generated entities, i.e., as part of cultural landscapes.

2. Materials and Methods: Beyond Resources, the Shaping of Nature

This study builds on past and contemporary debates regarding the concept of nature and its relation to “Non-Nature”, while also attempting to systematize the main variables of the study of past societies as a methodological framework for the analysis of contemporary contexts; this is based on bibliographic references and case studies using such methodological approaches.

This article argues that a tripartite conceptual framework, establishing an intermediate category between “nature” and “culture”, evolved alongside a dominant binary dichotomy. This third category, identified by 19th-century authors (Simmel, Reclus) following post-Kantian evolutionary philosophers (Hegel, Marx), is also present in phenomenological theories later on. Several key authors are quoted as examples of this approach (Drexler, Bloch, Febvre, Renfrew, and others), the purpose of the literary review being to illustrate, in a non-exhaustive manner, how the threefold approach evolved in parallel with a binary dichotomy that also persisted.

While being primarily a conceptual reflection, building from theoretical discussions, this study is strongly driven by the applied research undertaken by the author for several years, in different geographical contexts where prehistoric and other heritage studies and strategies of community-based management evolved to become triggers for landscape management processes. Such research encompassed the dimensions of science relevance [

23], education [

24], economic re-design [

25], culture–economy integration [

26], and heritage–transdisciplinarity interactions [

27,

28,

29].

This study is addressed to researchers interested in deepening the implications of conceptual understandings of contextual features; however, it proposes a framework of reasoning and project implementation that aims to reach site-based applied projects. In methodological terms, the reasoning of the text emerges from a praxis that attempts to overcome several dichotomies, including the divides between theory and practice, or between conceptualization and programming, as each of these “halves” continuously feeds the other within a framework integrated by the methods of the humanities, particularly historical assessment of transformations, cultural comparison, and textual criticism.

The study of the structural traits of past societies, based on essentially the same methods of research used for studying human performance [

30] in different historical periods, shows relative homogeneity or recurrence across time; otherwise, significantly different methodological frameworks would be required. Following this reasoning, the same methods and key analytical variables should also allow one to adequately describe and interpret the present.

When a historian or an archaeologist looks into the past, he or she will tend to seek patterns of continuity and discontinuity within some major variables, such as climate, technology, inequality, and governance. An example of how to identify recurrent patterns is to compare Montesquieu’s model of governance with traditional societies [

31,

32], identifying three main clusters of power (making laws, implementing them, and resolving disputes that arise under them, i.e., the rules of the parliament, the government, and the Court of Justice), where traditional societies present an age-based distribution of power and responsibilities (with the role of setting the rules given to the elders, the role of making daily decisions to the young adults, and the role of having the last word in deliberation to shamans or other knowledgeable individuals).

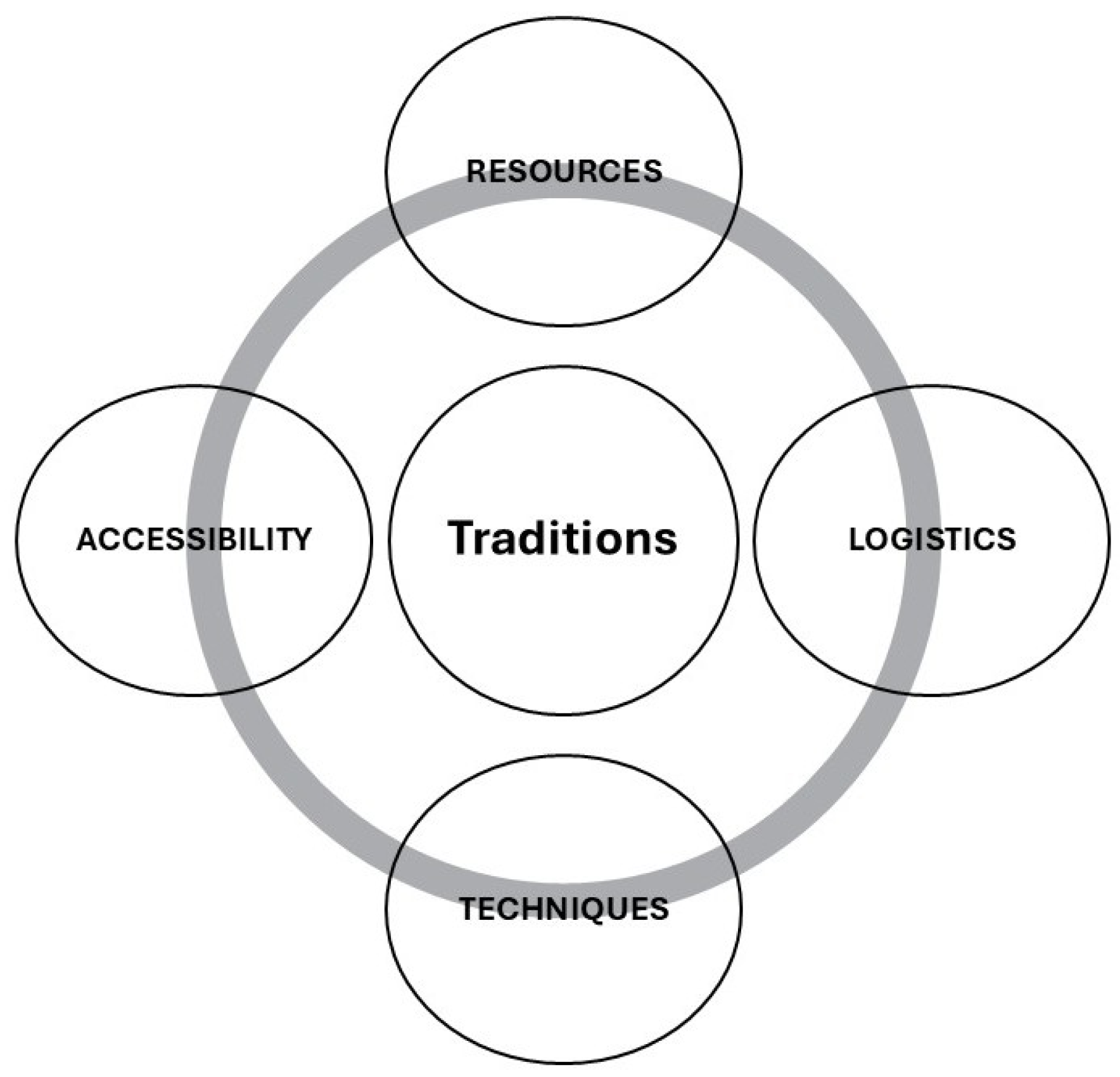

The study of the past entails accepting as true the fact that researchers can indeed reconstruct the structural dimensions of past behavior and its contextual constraints. There are four main drivers that historians take into consideration in all cultural contexts (see

Figure 1). The first is the environmental context itself, which allows for the assessment of the external conditions of human performance, i.e., the range of resources available to a given society. This first layer of any portrait of the past is then calibrated with the study of a second fundamental driver: the skills and techniques available at a given moment, i.e., the knowledge that allows any useful resources and technology available to be identified. These two variables structure the framework of possibilities in the mid- and long term, including the external (natural and other) and internal (anthropic) capacities, even though they are less precise when studying events. Together, they establish the framework of reference for studying a given society at a given moment [

33,

34,

35,

36].

However, the study of the past requires further characterization, and two more variables are systematically considered in most cases. The third common driver is the characterization of the available processes and mechanisms that bring together a society’s needs, resources, and techniques, i.e., the logistics, at a given moment in time. Finally, it is known that the availability of techniques and logistics does not imply that the whole of society has full access to them; hence, social differentiation and potential inequality also constitute a matter of interest when studying past societies.

The quantity of data available to assess each of these drivers may vary, but the above tend to be the four key dimensions of historical inquiry, which are weighted against the available information concerning previous historical moments for better understanding how they might have conditioned human performance in a certain period in history [

37]. Thus, historical research generates images of past human interaction with the wilderness and the progressive domestication of the latter, i.e., specific cultural landscapes in which humans exercised their growing dominium, beyond which the unknown and untamed (nature) or the domain of what cannot be characterized through the variables identified above would remain.

3. Nature and Human Agency: Perception Through Materialities

The study of the past is primarily anchored in tangible evidence concerning resources, techniques, logistics, and social structure, plus the inherited cultural framework forged by previous generations. Such an inherited cultural framework relates to knowledge and performative traditions, which shape the specific logistic and social performative transformations and explain why cultural diversity emerges even under similar material constraints (resources, available techniques, and logistic infrastructure).

While those constraints offer a range of possibilities, they do not determine performance, which largely emerges from the interaction between the social structure (and its imbalances and inequalities, as well as the direct experiences of interaction with the environment) [

38] and inherited culture (and related past experiences transmitted across generations through formal and informal education) [

39].

The first resource of human societies is their biological constitution. Although contemporary humans all belong to the same species, Homo sapiens sapiens, the history of humans is now understood as having been a complex mosaic of different related species and subspecies until not long ago. Although extinct variants of hominins are perceived as popular caricatures, such as in the case of Neanderthals, science now looks at them as expressions of a strong and flexible evolutionary matrix that only recently became restricted to a single variant, one that is now experiencing risk indicators in terms of its survival, namely, aging [

40] and a reduction in genetic diversity [

41]. The biological study of humans is not restricted to past evolution, however, as it also pervades the understanding of cultural evolution as a natural expression itself, governed by natural regulators (e.g., homeostasis, as suggested by António Damásio) [

42].

Likewise, an in-depth study of culture and cultural landscapes, if anchored in a naturalist approach, focuses on material evidence, which, in any case, dominates most studies of past societies in the absence of intangible evidence.

A specific historical cultural landscape (hl) can then be explained as the product of knowledge- and tradition-informed human agency (k), the materials ratio (resources and techniques, or r/t), and the performative ratio (logistics and accessibility, or l/a): hl = k (r/t) (l/a).

The knowledge dimension is built on fewer data than the other four dimensions because chronological sequence gaps are not uncommon, particularly in earlier periods of time, and culture as a whole can hardly be characterized based on material remains alone.

Such limitation relates to a major objective of the study of the past, which is the building of historical explanatory models [

43,

44].

Although mid- and long-term trends (the longue durée of F. Braudel) may be deduced from the first five variables, there is one fundamental dimension that, with rare and very limited exceptions, precludes the understanding of the causal nexus of short-term processes: the perceptions of the various actors at each given moment (the history of events, according to F. Braudel), except in more recent moments (even these are severely affected by memorial traps that tend to distort the historical past).

Yet, the perceptions of reality are the drivers of human decisions and are governed by the senses, touch, smell, taste, sound, and sight [

45], which operate in space, rather than in time. This triggers a potential divide between time-driven and space-driven approaches, as pointed out by E. Soja, 1989 [

46].

The complex mastering of the integrated approach to the time, space, and causal nexus of phenomena is a major adaptive advantage of humans. These are virtual competencies that require learning through experimentation before becoming abstract transferable concepts. The structuring of these competencies first follows a sensory intelligence approach, where the primary senses are touch and sound, as these are the first senses structured before birth that allow one to cognitively reconstruct the sense of distance through sounds and the perception of details through touch.

These senses remain very relevant throughout life, particularly in the early years of cognitive formation. Moreover, for this reason, they are important for communities in the dimensions of trust through touch and communication through sound.

These features are observable in the performance not only of traditional societies but also of more complex urban communities, for instance, in the role of touch in establishing interpersonal bonds or in that of sounds in publicity. There is a further reason for the biological prevalence of these two senses: the physical sense of touch, as reverberation, offers a kind of complex syncretic sensory experience that is structurally similar to prenatal experiences, which itself conveys a sense of trust.

This is important to understand when discussing the concepts of nature and landscape, as these are cultural constructs that do not escape the predominant role of the very strongly tangible senses of touch and hearing. Even the visual representation of a landscape tends to be a synthesis of such prior tangible sensory experiences, to which smell and taste add vicinity details that trigger notions of acceptance and integration or rejection and segregation. Odors and flavors therefore structure the boundaries of the domestic end of the wild, i.e., of the trustable, harmonious, and predictable anthropic space, when compared with the chaotic, untamed, and unpredictable natural space [

47].

Sight is, of course, very important in producing the synthesis of these perceptions, and images are easily shareable compared with the inputs conveyed by other senses [

48]. This is because the experimental cognition based on the other senses suffers from a greater impact of biological diversity among humans, in terms of their capacity to identify diversity through sounds, smells, or flavors, while touch has a limited spatial range of impact. However, when it comes to studying the relevance of sight, this relates to the process of building mental images through experiences that are less tangible than what concerns the other senses [

49].

This is why it is apparently easier to establish a mental image that illustrates, at a given moment, a society’s shared perception of a specific phenomenon, be it a syncretic image of contemporary “nature”, the image of a paleolithic society, or the image of migration flows in contemporary society. All these are shaped by indirect experiences, which are themselves dependent much more on the other senses; therefore, the collective image of a feature allows for a range of diverse detailed understandings greater than what a single, tangible, rooted perception would allow.

Human agency, however, is driven primarily by these site-based images, which we name landscapes. As a result, the same feature will be perceived as a different landscape according to the cultural background of the community (its perspective), which will select different details informed by a large range of individual tangible experiences and perspectives and harmonize them through a minimum common ground of agreement, itself related to socioeconomic interactions, related values, and collective experiences.

While individual perceptions are primarily structured through tangible experiences (in the sense of the concept of taskscapes, as defined by Tim Ingold), collective perceptions may still integrate a certain degree of such tangibility (namely, through working activities or rituals), but they require a degree of abstraction that allows the community, itself a potentially divided unit, to build a shared common understanding of the context, i.e., a landscape [

50]. This common understanding is structured through interactions between the physical features’ morphologies, the community practices, and the interactions cutting across both, as suggested by J. Stephenson [

51].

In this sense, landscapes (as perceived spaces) are structured through human activities (taskscapes), which relate to the technology and logistics drivers of historical studies and the tangible dimension of sensory cognition, particularly concerning the non-visual senses [

52]. As such, they are the domain of the anthropic, as opposed to the domain of non-anthropic nature (or wilderness).

The understanding of Amazonia (which is a strongly human-induced landscape) as a wild or natural environment illustrates why and how the room for nature is reduced through the expansion of the “domesticated”/anthropic areas. Along the same lines, it is interesting to see how the main biotopes of contemporary Brazil have been renamed from their original indigenous (Tupi) names. In the Tupi language, the dense Atlantic Forest was named Caa-eté (the “true forest”), the dry savanna biome was named Ca’atã (the “hard forest”), and the semi-arid scrub coverage was called Caatinga (the “white forest”). Out of the three, only the last indigenous name survived, because while the other two referred to spaces which had similarities to landscapes in Africa, already familiar to the Europeans (i.e., spaces that they knew how to use and transform), the last one referred to a new form of true nature, i.e., nature that was still the terrain of the unknown, the unnamed, and the untamed [

53].

4. Nature and Landscape: Anticipation and Utopia

As discussed above, although a landscape is a perception that is strongly associated with an image, the identification and embodiment of a landscape resides in its tangible basis (senses, techniques, and logistics), as it is acknowledged in Stedman’s [

54] description of place as being driven by physical features, rather than the narrative of its allegedly untamed, wild components. In this sense, nature became a growingly restricted space, even if some anthropic taskscapes, such as Amazonia (with its human-manipulated forest) [

55], Antarctica (with its scientific expedition remains) [

56], the Oceans (with the accumulation of anthropic waste) [

57], and Greenland (with its strong traces of colonization during the Medieval warm period) [

58], may still be perceived as “natural” by those unaware of such anthropic impacts.

For instance, the representation of a mostly inhabited space, such as Greenland, corresponds in fact to an anthropic landscape, not only due to its long-lasting human dwelling but also because the action of describing it (in terms of resources, available techniques, existing and potential logistics, and social accessibility) immediately incorporates it into the domesticated sphere and thus detaches it from “nature” (even when it might still be named as such).

Landscapes are, in the end, perceived blended spaces in which anthropic and other traits are intertwined, but that the observers experience [

59] as possibilities for anthropic transformation, in whichever direction, from industrialization to forest regeneration. They are not nature, because nature is primarily driven by itself, i.e., by non-anthropic factors.

The contemporary dominant belief of major human control over climate, expressed through the notion of the Anthropocene, is the ultimate expression of such an anthropic perception, which opposes pre-industrial societies’ traditional perceptions of nature as wilderness and untamable, thus precluding any possibility of positive outcomes from transformative actions. Landscape is a product of modernity, not because of the ecological impacts of urban concentration and industrial pollution but due to the modern program that generated the notion of one Earth (instead of a series of ethnocentric places), one humanity (and not a mere juxtaposition of disparate cultures), and one common transformative sense (and not a perpetual return in cycles).

It is the idea of transformation that requires moving from dichotomies (as in nature versus culture) to flexible concepts of transition and mixture (as in not only landscapes but also the concepts of middle class and its instability, human rights with their possibilities and shortcomings, or democracy as a permanent balance). For contemporary societies, nature no longer exists, not even on the Moon, having become a terrain of dispute among human competitors [

60].

This implies that the management of the so-called natural resources should follow, fundamentally, the same criteria of cultural landscapes, i.e., units of intertwined human and non-anthropic performance. By incorporating such a notion, it is not human agency alone that is to be considered, but also the other agents of performance and their overall equilibrium, which is, from a human cultural perspective (the only one humans can have), a cultural landscape.

The construction of a cultural landscape, being structured through agency, sets a divide that excludes, as different, dangerous, or wild, everything that is insufficiently understood and that therefore cannot be included within such a cultural landscape (G. Bachelard) [

61]. Such construction builds on perception (anchored in the intensification of human activities and their interactions), techniques and their products (extensions of the human body, as A. Leroi-Gourhan said) [

62], oral and fossil communications (through rituals and myths), images that emerge as collective abstractions portraying the present through the reconstruction of images of the past (memories) and of the future (utopia and dystopia), and behavioral norms that preclude disruption with the cultural landscape (values and laws).

Furthermore, cultural understandings, while having been recognized to be dependent on nature and its early representations, such as the ancient Greeks’ Pantheon (expressed by the action of Prometheus, who domesticated fire to improve technology) [

63], also incorporate the awareness of the inherent risks of such a process (as illustrated both in the punishment of Prometheus and the fate of Icarus) [

64].

In this context, human agency is oriented towards anticipation, with humans attempting to satisfy their needs through will, as Nietzsche argued [

65], and perceived resources (including other humans), transforming them and improving the logistics connecting both.

However, anticipation and the forecasting of its driving goal, even when informed by academic knowledge, are, at least partially, dependent upon belief, since no forecasting effort can fully determine all possible variables. One major reason for such a limitation is that while causality schemes (which are essential to forecasting) are supported by human agency and techniques in the interplay of space and time, the understanding of time is potentially limited compared with the space dimensions.

Cultural landscapes (see

Figure 2), although dynamic, tend to build primarily on the characterization of an anthropic (non-wild) space with six core variables to compensate for this limitation: poetics (creation through agency), aesthetics (equilibrium and homeostasis), imitation (identification and identity), narrative (meaning), metaphysics (sense), and pragmatics (resources or usable components). These are then complemented by two more variables, which, starting from the space attributes, provide a time dimension: tradition (the reading key of values that frames the interpretation of features) and transformation (the trigger for change, driven by adaptation needs).

These eight drivers are present in the community-based (common sense) co-construction of cultural landscapes, as they offer a reasonable and dynamic description of a landscape, which can then be further approached from the perspective of adaptive strategies (the main role of academia) and its wider transformation (with significant contributions from creativity, utopia, and art).

A sustainable approach to resource management should start, based on the considerations above, with the description of the context within the above variables and sub-variables. This becomes particularly important in present times, with globalization having reached its maximum and encompassing almost the whole planet, thus generating a common planetarian landscape.

This became very evident during the pandemic, when despite several discrepancies among governments and top-down decisions, a unique, convergent pro-life response occurred for the first time ever, cutting across any other divides [

66]. Such a convergence in giving priority to saving lives rather than protecting economies countered all previous responses to epidemics, as described by abundant research, possibly resulting from a consolidation of the notion of humanity based on the ethics of personal dignity.

This common landscape, which calls for a sense of communality among humans, still faces tensions in terms of ethnocentric inheritance and the illusion that globalization is an ideological program rather than a human–cultural material process guided by homeostasis or other driving processes. However, as in previous episodes of counter-globalization in the past (e.g., at the dawn of the Bronze Age or the early Middle Ages in Europe), the materiality of the process either pursues integration or aggravates tensions and wars.

5. Nature as a Cultural Landscape: Communities and Transformation

At the pace of the expansion of cultural landscapes, the notion of nature becomes itself a cultural perception, i.e., a landscape informed by materialities but driven by perceptions and agency. This is particularly evident in the identification of certain contexts as being untouched by human agency, despite historical evidence to the contrary (e.g., Amazonia). Once the “tamed” spaces tend to cover the whole planet, the notion of nature as a sort of balanced ecological paradise being lost, is a strong perceived landscape.

Understanding nature as a cultural landscape, or a set of units of intertwined human and non-anthropic performance, allows not only more balanced and sustainable approaches to resource management to be co-designed, but also cultural diversity to be protected as a major expression of human identity through the overcoming of the illusory contradiction between the unity and diversity of humans, considering the relation between humans and non-humans as part of human behavior itself.

Such an understanding resumes the approach of many traditional societies’ ontological understanding of humans, or themselves, as being part of a whole living complex, in which the performance of the group prevails over individual agency. The positive connotation of the word “landscape” itself, building from painting and oriented towards harmony, echoes notions such as “Yvy Marae” (the land without evil, a notion of the Guarani people in Southern America) [

67], or “ukukhonza” (the prevalence of groups over individuals, anchored in the notion of ubuntu, among the AmaZulu communities in South Africa) [

68].

The understanding of nature as a cultural landscape is the foundation of the project of integrated actions of landscape management (AIGPs in Portuguese) that is being structured in Portugal. The episodes of seasonal fires in the Mediterranean climatic region, which includes Portugal, are a recurrent feature that becomes part of the image of the region every summer. The combination of high temperatures and low humidity favored, from prehistoric times, the regular renewing of the biomass coverage through fire, engaging a process of soil regeneration with strong edaphological implications, which were observed and often copied by human communities since prehistoric times, through slash and burn practices. While this was regarded as a positive and productive natural process, in the last few decades, fires in the region became more frequent, wider, and with predominantly destructive consequences, often gaining the designation of “wild fires” and becoming defined as “uncontrolled fires that occur in nature and are often harshened by climatic conditions” [

69].

Perceived as a continuation of a natural phenomenon, aggravated by depopulation and a very divided property model, the management of these fires focused on fire-fighting mechanisms (firemen accessibility, aerial resources, etc.) and techniques of landscape protection against fire, such as clearing, both based on fire inevitability resulting from the natural characteristics of the landscape [

70].

Against the background of the recurrent catastrophic fires that ravage Portugal and southern Europe every year, the AIGPs program combines a rigorous assessment of the technical details of fire propagation, ongoing landscape management, and the historical models of territorial adaptations, to shift the focus from fire prevention or forest recovery, which was dominant in recent decades without success, to the profound re-design of landscape management models in line with the logic of adaptation to natural phenomena.

The underlying argument was to focus first, not on forest recovery, fire prevention, or firefighting, but on landscape harmony building from its physical properties (possibilities) combined with a (sustainable) redesign of its use. The new approach started by acknowledging the main social and economic changes in the past decades, namely the replacement of an agriculture-based economy by the 1960s (38.5% of the economy and 42% of labor in 1960) by a services economy in which agriculture became a minor economic and social sector (2.9% of the economy and 2.7% of labor in 2024), having rural exodus and aging as major consequences. The economic usefulness of this territory for a services-oriented economy decreased, and the retrieval of biomass that used to be part of the rural economy ceased. However, an attachment of the diaspora of rural migrants to those areas persisted, as part of their identities, meaning, and sense of belonging.

It was based on the community’s attachment to their ancestral land that a new strategy was conceived: to foresee a new organization of a productive and harmonious landscape, based on the cultural perceptions and structured through new sustainable activities (from fruit cultivation to environmental protection), engaging the whole of the population and their knowledge and needs as leading partners in the process, thus also encompassing a transdisciplinary dimension.

This radical shift, anchored in a solid understanding of past risks, allows us to move from a merely defensive approach to an active transformation of behavior patterns for the future. In such a project, all economic, social, cultural, and environmental variables, among others, are taken into consideration not fragmentarily but as the integrated core of all solutions. In other words, it is by moving beyond the nature/culture divide into a human-driven landscape understanding that resilient transformative practices can be developed [

71].

This is also the core of the rock art trail project in Mato Grande do Sul, Brazil. In this case, the discovery of relevant rock art heritage [

72], in a region subject to very strong environmental and social imbalances, prompted the co-design of an integrated project that builds on archaeological research to focus on seven other articulated concerns, from education to the creation of jobs.

The project is centered in the area of Alcinópolis, in the extreme north of the state, sitting in the Cerrado biome (a kind of savannah), but not distant from the wetlands of the Pantanal biome (itself a subsystem of the Amazonian rainforest). The dominant approach to this kind of territory has been the dichotomy between environmental preservation and the need for economic growth, generating several tensions (including between different human communities), processes of social exclusion (poverty, marginalization of Indigenous communities), and environmental negative impacts (namely the replacement of protected forest by pasture land), as part of an accelerated economic re-design in the past few decades [

73].

Moving away from this nature–culture divide, but also from the dichotomy between economy and cultural heritage, a project engaging several stakeholders (from the university and local authorities to entrepreneurs and communities) started a re-conceptualization of the region through the structuring of a cultural itinerary, anchored on a very important cluster of prehistoric and indigenous rock art sites. The so-called “Rock Art Trail” integrates the study and management of the cultural heritage places with tourism and other economic activities, but also with education, communication systems, craftmanship, bio-industries, and potentially all the dimensions of human performance, also revisiting the ecological divide between the Pantanal and the Cerrado divide as an ecological integrated ecotonal region. By engaging with local communities and their traditional systems of knowledge and creation, the project also embraces a strong transdisciplinary dimension.

As in the case of Portugal, the core of the project is integration through the co-design of solutions, in which historical and archaeological knowledge of the past is used as a lever for forecasting and social transformation [

74]. In both cases, the ongoing transformative projects have a transdisciplinary dimension and call for perceiving human–nature and human–human interactions through the opportunity to conceive new non-dichotomic divides, i.e., calling for designing new landscapes that build from community-based utopias.

6. Nature and Landscape Management: Governance and Education

The management of natural resources, as components of cultural landscapes, relates to the assessment of their contribution to the meeting of various needs, both in the short term and in the mid- to long term; this includes ethical considerations, which are possible once the absolute faith in emancipation through technology has been put into question [

75,

76].

If resources are managed only from the perspective of meeting short-term needs, ethical concerns will tend to be restricted to balancing the use of those resources, namely, securing equitable access to them, and the need to preserve the environment of living communities, thus protecting their landscapes and sense of belonging. The limited awareness of short-term needs will, therefore, trigger short-term solutions, without major consideration of their longer-term effects.

It is the understanding of the meaning of life as part of a longer-term agenda, itself a cultural understanding, that leads to the consideration of not only the balance between the usability of resources and the preservation of places, but also the systemic preservation of the environment as a condition for the preservation of collective identities. In other words, it is by humanizing nature that the latter can be the subject of a sustainable strategy of preservation, because it will become a strategy of self-preservation.

It is by no accident that, although nature is often claimed as a reference to follow in human behavior norms, many different and contradictory strategies claim their affiliation to nature, thus suggesting that those norms are in no case inherent in nature but originate in the minds of humans [

77].

However, human understandings are not biologically given; they are constructs based on shared knowledge, i.e., reasoned convergent agreement. This can be the result of a random set of arguments, which will tend to produce several minority beliefs and promote tensions and contradictions between those arguments, or the outcome of methodologically driven reasoning, integrating different forms of knowledge within a formalization framework served by academia, i.e., an established method within a transdisciplinary knowledge framework [

78].

Understanding natural resource management as part of cultural landscape management, anchored in the co-construction of shared knowledge, requires an education program in order to reach a consensus on the temporal flow that may bind together past experiences, present perceived needs, and future utopias. In methodological terms, this is what has been successfully achieved in modernity by integrating the industrial globalization economic aims with the disruptive legal constitution of citizenship as the foundation of the new system (itself a byproduct of the renaissance notion of humankind), with such citizenship being created with the fundamental education of individuals (public instruction) and a continuous program of knowledge updating (mainly through civic museums, but also through Arts and Sciences fairs, such as the world fairs in the 19th and early 20th centuries) [

79,

80].

This mechanism of fundamental and continuous education was already present in pre-modern and more unequal societies but only targeted the social elites that could access power and decision making, from the ancient Greeks’ Gymnasium to the royal collections where European leadership was educated, before they became themselves museums for the people, such as the Hermitage and the Louvre.

Past successful societies understood the importance of education throughout life for their management and governance, investing in what we now call schools, universities, and museums. The challenges offered to contemporary societies are certainly different from those in classical times or in modernity, but the methodological approach to social cohesion through knowledge and its education cuts across those differences, because it is the human expression of a certain kind of primate behavior that has been improved and expanded in the human species: the capacity to learn and generate new knowledge, throughout one’s whole life.

The importance of education, including heritage education, resides in the biological characteristic of humans of being an ever-learning species [

81], which is maturated through individual interaction experiences, i.e., experiences that are not necessarily shared by other humans, which thus generate different understandings, mindsets, values, and forecasts, potentially as a kaleidoscope of divides. Education, therefore, should be primarily perceived not as a path for social improvement or a segment of the market of products to be exchanged, but as the primary precondition for governance and sustainability [

82].

Because governance and sustainability, which are necessary to prevent dystopia, are fundamental aims of landscape management, a cultural strategy should start by overcoming any remains of a divide between nature and culture and merging the understanding of both as one, instead of an arithmetic set of checks and balances between human needs and mitigation strategies to preserve a reified notion of nature, achieving the integration of humankind and its algebraic interactions.

This is where the notion of landscape, as argued above, becomes particularly useful. However, it is also in this context that the museum, as the echo of school throughout life, finds its core purpose.

The establishment of museums or related structures, not as commodities but as civic education knowledge hubs for the co-construction of knowledge, can play a central role in facilitating convergence across the contemporary divides and different interests and perceptions, as well as overcoming the growing separation between individuals and institutions, which was achieved under stressful constraints during the pandemic based on an ethics of non-segregation of the infected.

Museums and their collections may foster debates on the plurality of understandings of the past and on the shared nature of that past, beyond all its often-traumatic divides, contributing to putting the focus primarily on methodologies to move forward rather than on goals to be achieved, which may prove to be particularly important in times of uncertainty [

83].

Museums contribute to putting the focus on processes, the complexity of adaptation mechanisms, and the means for integrating long time series and extended space contextualization. They can perform as tools for resistance against approaches focused on isolated moments or sound bites (e.g., discoveries and monuments) and demonstrate how knowledge has been the key adaptive strategy of humans over time. In this context, engaging citizens in knowledge building, for instance, through participatory sciences and scientific experiments, improves trust in academic knowledge and stimulates the mastery of the understanding of interactions between special features and time series, in turn, allowing for the understanding of immanent causality and forecasting.

The link between forecasting and materialities is not to be found in the aims but in the path (what some people call the “bottom-up” approach) and the structures that support it within landscape management. Museums and related structures, such as memory spaces or forums of debate, alongside a fundamental education program, are the two main pillars of a sustainable landscape management strategy (i.e., one that will not only secure mid–long-term continuity but also remain stable during too-short cycles of change determined by extreme divides).

It is continuity that enables the design of sustainable strategies, it is governance that can secure stability, and it is critical knowledge that can secure governance.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we have argued that, besides a dichotomic understanding of human–nature relations, a more complex notion emerged from early societies, becoming consolidated in theoretical terms in late modernity through the concept of landscape: an ideal of tamed nature perceived as a harmonious utopia, not driven by mere resource exploitation. The paper builds from the comparative methodologies of the humanities, approaching the theme through a long time series framed within four main variables of past societies and traditions assessment: resources, techniques, logistics, and accessibility.

The main implications of applying this methodological framework are as follows: the understanding of the relation between the concepts of landscape and evolution in modernity, anchored on knowledge and structured through perceptions and agency (

Section 3); the understanding of landscape as a cultural construct that structures anticipation and utopia through eight main drivers: poetics, aesthetics, imitation, narrative, metaphysics, pragmatics, tradition, and transformation (

Section 4); the understanding that the predominant use of the notion of nature is, itself, a cultural landscape that allows for the engagement of community-based transformative actions (

Section 5); and the understanding of the relevance of education in the process of landscape perception, conceptualization, and governance (

Section 6).

Sustainable resource management focuses on the preservation of biodiversity and cultural diversity as part of its needs. Therefore, a flexible institutional backbone is needed to overcome the divide between nature and culture (e.g., understanding the lithium landscape not only as a resource to use in more sustainable energy production but also as a resource for the identity of human communities) and to frame debates and conflicts as part of a cultural landscape of discussions served by an established methodological framework. Education and museum-related structures (such as libraries) can become such an institutional backbone.

When landscapes become understood not as mere co-designed spaces but as clusters of different but convergent perspectives, they may play an important role in resuming convergence and equilibrium among societies, clarifying their contradictions but also their commonalities and shared needs, while structuring tasks that may lead to such convergence (peace remaining, since Kant, the main guiding utopia, still valid in the present).

This powerful combination, which resumes past frameworks such as the educational model of Confucius in Asia [

84] or the medieval praxis of universities in Europe [

85], allows different stakeholders to be brought together in co-designing and implementing initiatives that address different perceived needs, avoiding paralysis and disruption.

For instance, the use of some resources, such as lithium or gas, should build on society’s clear understanding of its implications, which should not be based on the reduced opposition between “good” and “bad”, as it is a dilemma to address and manage as a cultural choice.

This is the concept underlying the newly approved program of UNESCO, BRIDGES [

86], which stresses the need to “value contextualized approaches, diversity, contradiction, and robust understandings of sustainability challenges”; to “understand the Earth not solely as a planetary system, nor as a reservoir of resources, but as a web of meanings and interactions that is inherently multilayered and pluralistic”; and “to establish a world of new relationships, based on dialogue and co-design, among the co-inhabitants of the Earth”.