Characteristics of Microbial Communities in Sediments from Culture Areas of Meretrix meretrix

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

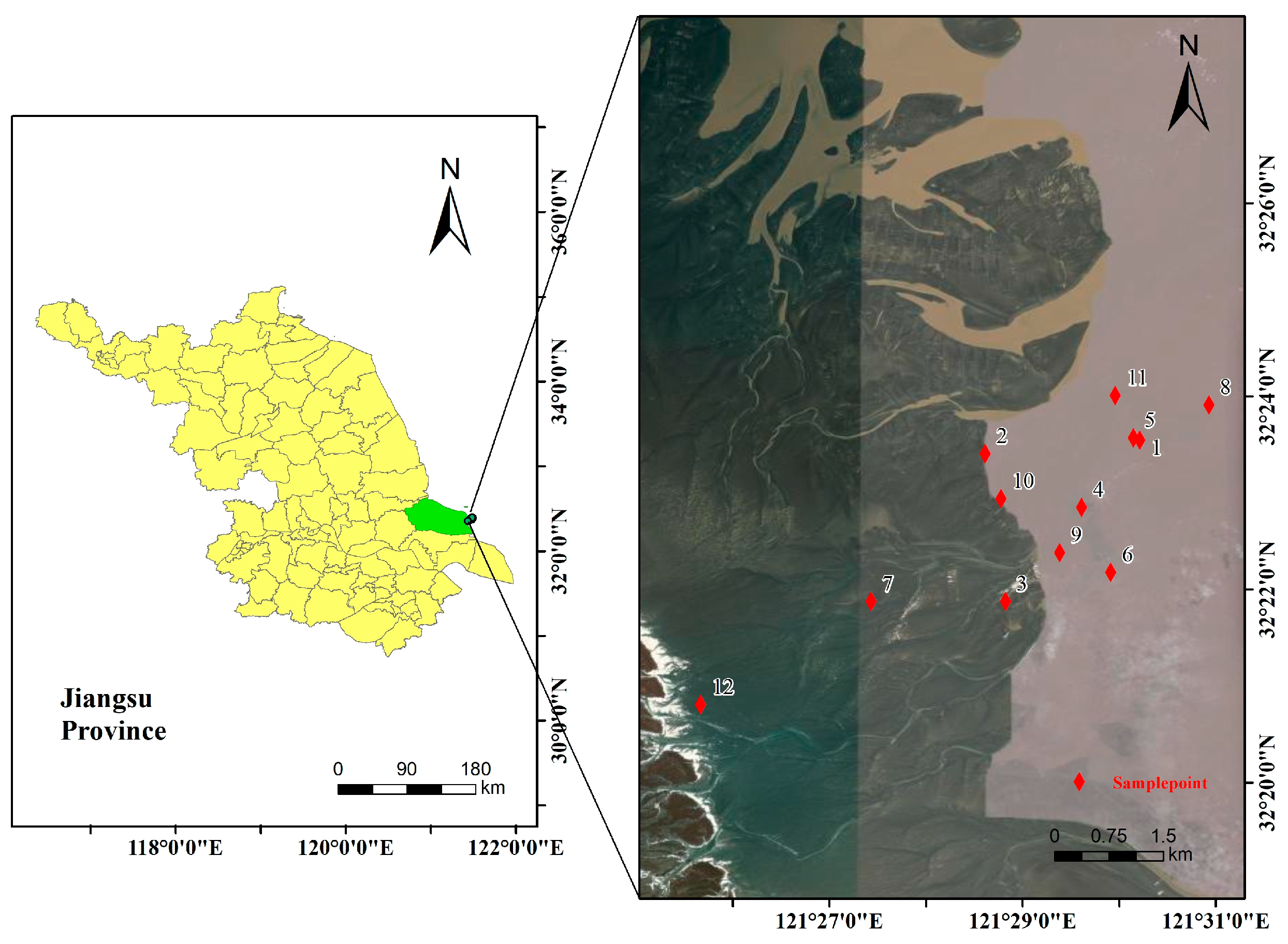

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Determination of Water and Sediment Sample Indexes

2.3. Microorganism High-Throughput Sequencing

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of Sediments in the Culture Area of Meretrix meretrix

3.2. Analysis of Microbial Community Diversity in Sediments

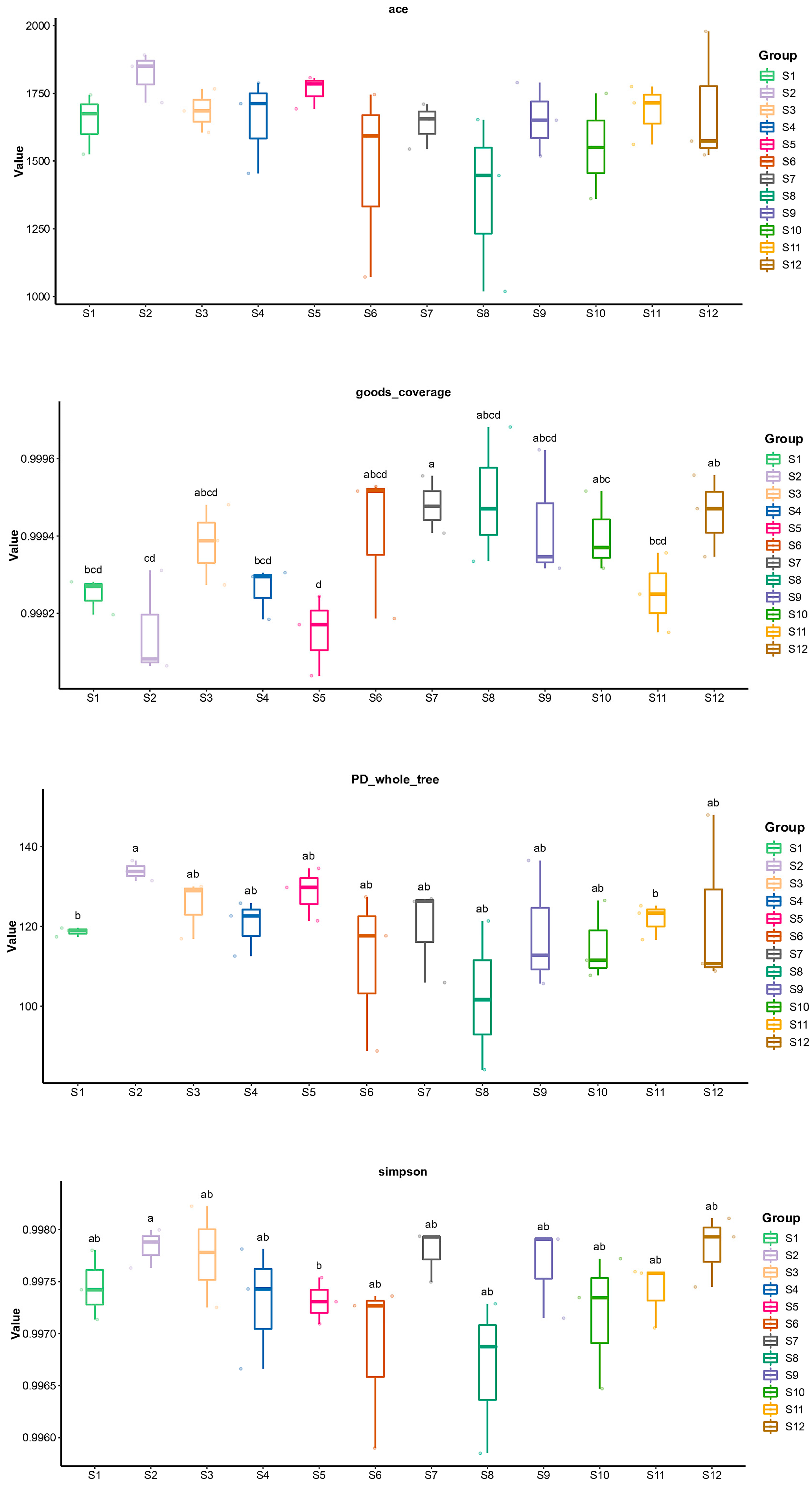

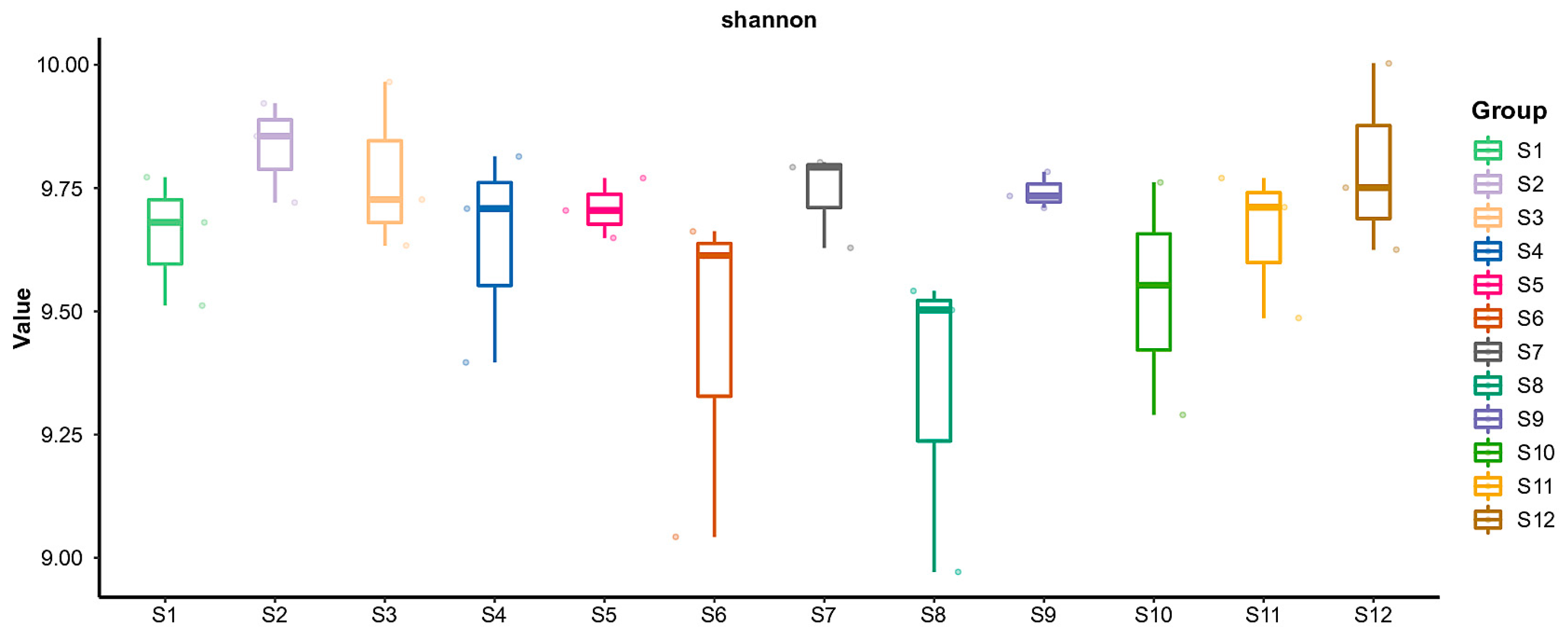

3.2.1. Alpha Diversity Index Analysis Results

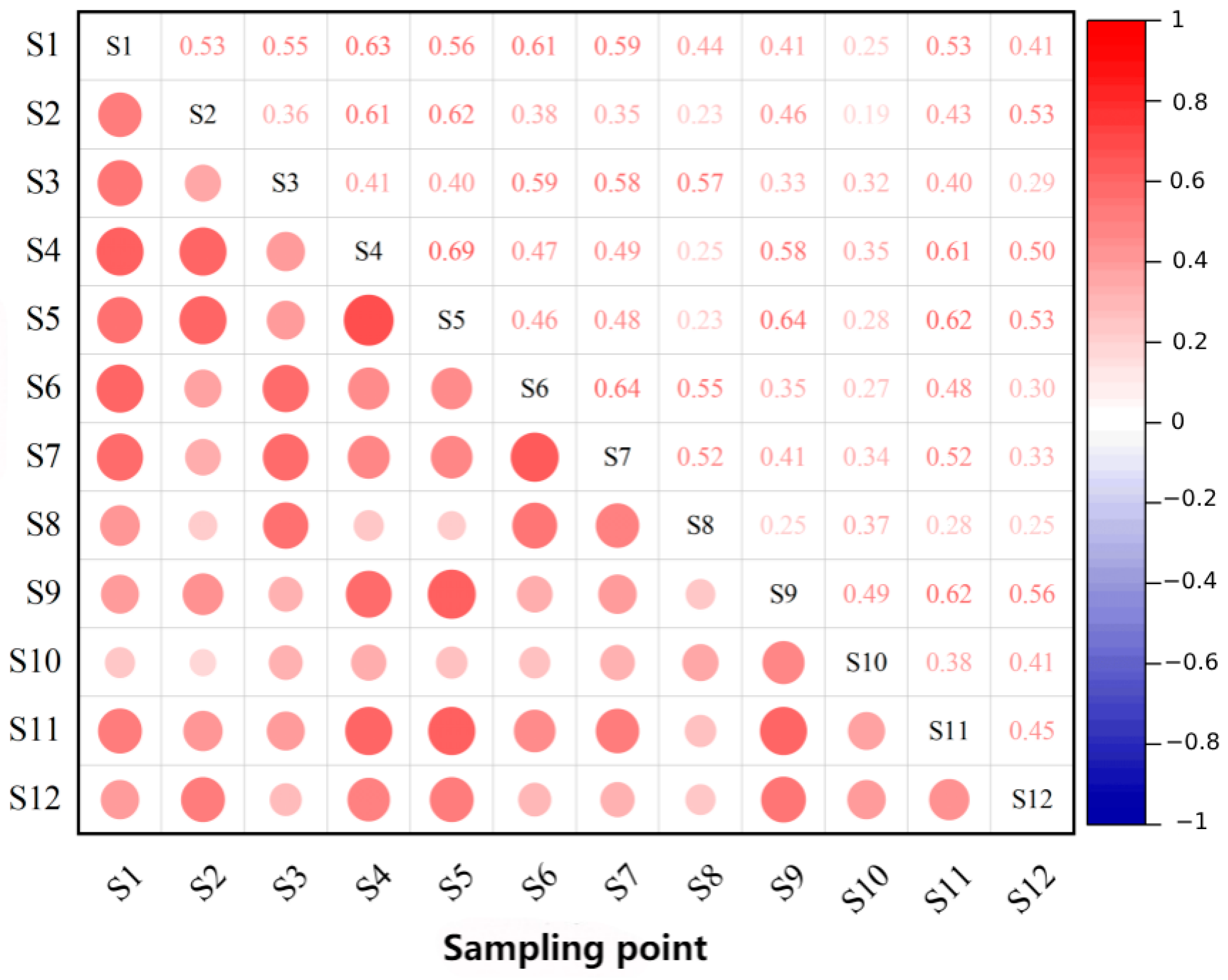

3.2.2. Beta Diversity Analysis Results

3.3. Composition of Microbial Community Structure in Sediments

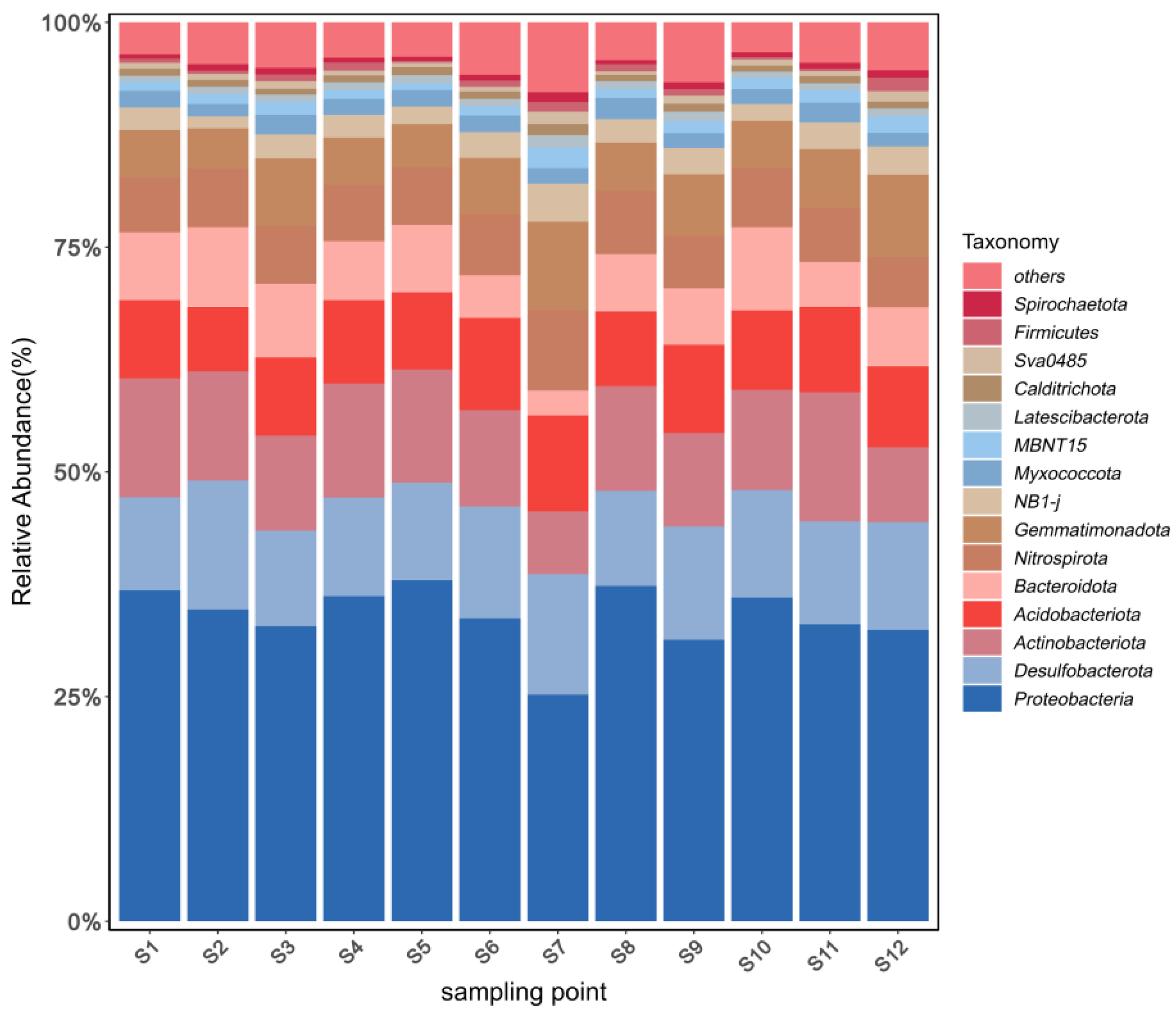

3.3.1. Phylum-Level Microbial Community Structure

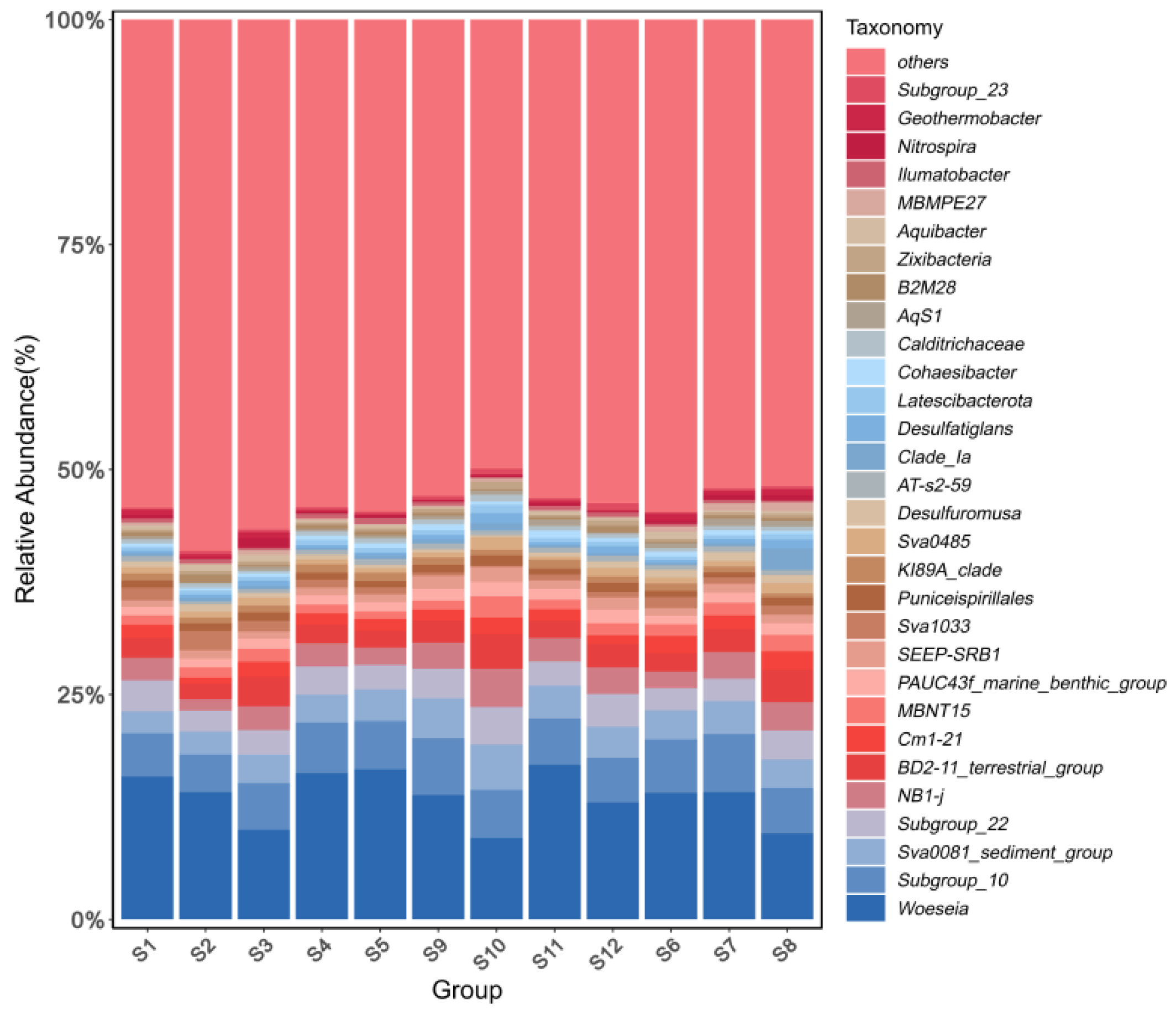

3.3.2. Horizontal Microbial Community Structure

3.4. Correlation Between Microbial Community Structure and Environmental Factors

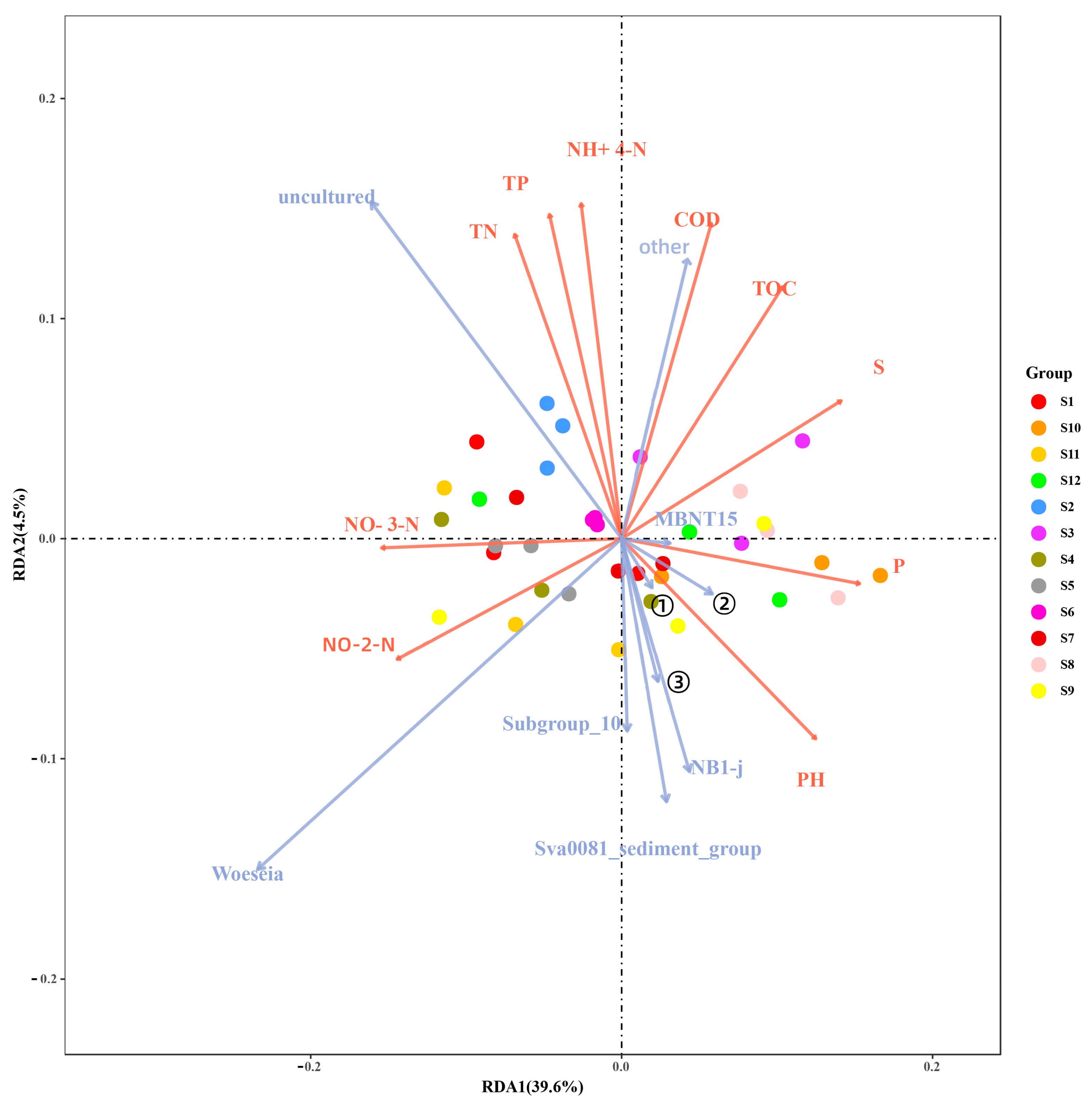

3.4.1. Redundancy Analysis Results and Their Interpretation

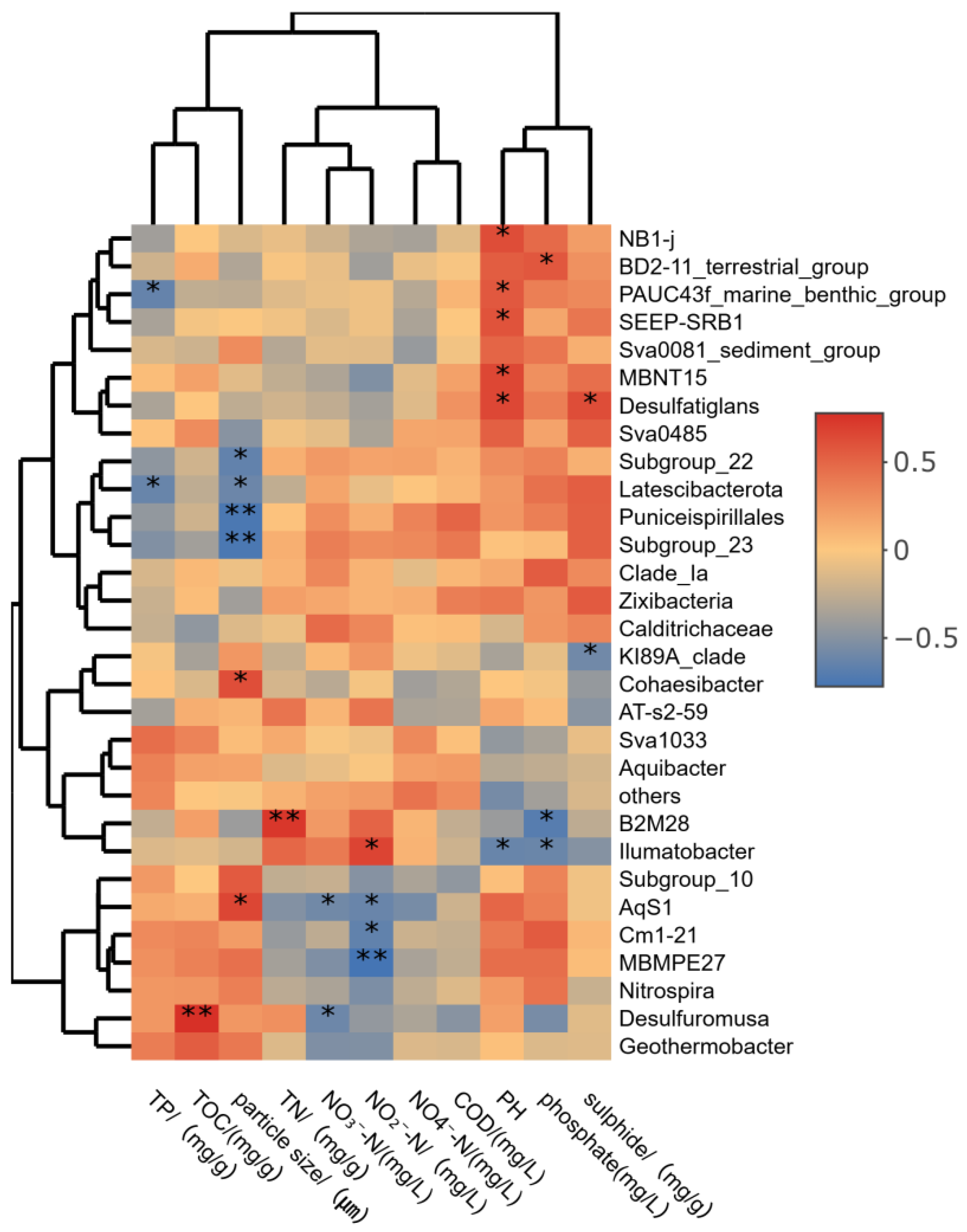

3.4.2. Correlation Analysis Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Nutrient Pollution and Microbial Community Diversity in Sediments and Water of Meretrix meretrix Culture Area in Rudong

4.2. Characteristics of Microbial Community Structure in Sediments

4.3. Correlation Analysis Between Microbial Population and Environmental Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, K.; Jianfeng, T.; Zaiyang, Z.; Stefan, A.; Bing, W.Z. Sediment Characteristics and Intertidal Beach Slopes along the Jiangsu Coast, China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P.G.; Fenchel, T.; Delong, E.F. The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth’s Biogeochemical Cycles. Science 2008, 320, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinichi, S.; Pedro, C.L.; Samuel, C.; Roat, K.J.; Karine, L.; Guillem, S.; Bardya, D.; Georg, Z.; Mende, D.R.; Adriana, A.; et al. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 2015, 348, 1261359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, F.; Han, D.; Wang, G.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, D.; Rong, N.; Yang, S. Characteristics of bacterial community structure in the sediment of Chishui River (China) and the response to environmental factors. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2024, 263, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Bai, J.; Gao, H.; Wen, X.; Zhang, G.; Cui, B.; Liu, X. In situ soil net nitrogen mineralization in coastal salt marshes (Suaeda salsa) with different flooding periods in a Chinese estuary. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 717-2014; Soil Quality-Determination of Total Nitrogen-Kjeldahl Method. Department of Science and Technology Standards. Ministry of Environmental Protection: Beijing, China, 2011.

- HJ 632-2011; Soil-Determination of Total Phosphorus-Alkali Fusion-Molybdenum Antimony Anti-Spectrophotometric Method. Department of Science and Technology Standards. Ministry of Environmental Protection: Beijing, China, 2011.

- GB 17378.5-2007; Specifications for Marine Monitoring-Part 5: Sediment Analysis. National Marine Environmental Monitoring Center: Dalian, China, 2007.

- GB 17378.4-2007; Specifications for Marine Monitoring-Part 4: Analysis of Seawater. National Marine Environmental Monitoring Center: Dalian, China, 2007.

- Magurran, A.E. Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, O.A.; Tippett, R.; Murphy, K.J. Seasonal changes in phytoplankton community structure in relation to physico-chemical factors in Loch Lomond, Scotland. Hydrobiologia 1997, 350, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reta, G.; Dong, X.; Li, Z.; Bo, H.; Yu, D.; Wan, H.; Su, B. Application of Single Factor and Multi-Factor Pollution Indices Assessment for Human-Impacted River Basins: Water Quality Classification and Pollution Indicators. Nat. Environ. Polution Technol. 2019, 18, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, D.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Wen, J. Distribution characteristics and pollution assessment of nutrients and heavy metals in sediments of huangbai river cascade reservoirs. J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 30, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkyu, C.; Chul, K.H.; Woon, H.D.; Seok, L.I.; Sook, K.Y.; Jung, K.Y.; Gu, C.H. Organic Enrichment and Pollution in Surface Sediments from Shellfish Farming in Yeoja Bay and Gangjin Bay, Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 46, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranford, P.J.; Strain, P.M.; Dowd, M.; Hargrave, B.T.; Grant, J.; Archambault, M. Influence of mussel aquaculture on nitrogen dynamics in a nutrient enriched coastal embayment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 347, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, H.; Pilditch, C.A.; Bell, D.G. Sedimentation from mussel (Perna canaliculus) culture in the Firth of Thames, New Zealand: Impacts on sediment oxygen and nutrient fluxes. Aquaculture 2006, 261, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmer, M.; Wildish, D.; Hargrave, B. Organic Enrichment from Marine Finfish Aquaculture and Effects on Sediment Biogeochemical Processes. In Environmental Effects of Marine Finfish Aquaculture; Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.G.; Hawkins, A.J.S.; Bricker, S.B. Management of productivity, environmental effects and profitability of shellfish aquaculture—The Farm Aquaculture Resource Management (FARM) model. Aquaculture 2007, 264, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Study on the Species Composition and Quantitative Variation of Phytoplankton in the Nearshore Waters of the Bohai Sea. Mar. Fish. Res. 2003, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, X.; Cui, L. Investigation and Evaluation of Water Quality in Shellfish Farming Areas of Laizhou Bay. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 76–79+122. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Liu, T.; Zheng, M.; Gao, P.; Du, G.; Qu, L. Structural Characteristics of Marine Microbial Communities in Rizhao Shellfish Farming Areas and Their Influencing Factors. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2023, 41, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L. Microbial Community in Eutrophic Taihu Lake Sediments and Its Response to Environmental Factors. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2019, 25, 1470−1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengdie, G.; Weizhen, Z.; Ting, H.; Rong, W.; Jianjun, W.; Xiaoying, C. Eutrophication causes microbial community homogenization via modulating generalist species. Water Res. 2022, 210, 118003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulsford, S.A.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Driscoll, D.A. A succession of theories: Purging redundancy from disturbance theory. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2016, 91, 148−167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sophie, C.; Eunsoo, K.; Ajit, S.; Joseph, M.; Solange, D. Small pigmented eukaryote assemblages of the western tropical North Atlantic around the Amazon River plume during spring discharge. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16200−16200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, J.A.; Hollins, A.; McCarty, A.J.; Martinez, G.; Cui, M.; Gomes, M.L.; Fuchsman, C.A. Microbial diversity and abundance vary along salinity, oxygen, and particle size gradients in the Chesapeake Bay. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 26, e16557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisa, B.; Paola, D.N.; Mauro, C.; Francesca, M. Sediment Features and Human Activities Structure the Surface Microbial Communities of the Venice Lagoon 13. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhu, L.; Mao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yang, A.; Zhu, W.; Zhuang, Z. Analysis of Sediment Microbial Community Structure under Different Aquaculture Models in Nansha Islands, Xiangshan Port. Adv. Fish. Sci. 2014, 35, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Niculina, M.; Ursula, W.; Katrin, K.; Steffen, K.; Tanja, D.; van Beusekom, J.E.; Dirk, d.B.; Nicole, D.; Rudolf, A. Microbial community structure of sandy intertidal sediments in the North Sea, Sylt-Rømø Basin, Wadden Sea. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 29, 333−348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Zhang, T.; Zou, Z.; Yang, Z. Vertical distribution characteristics and influencing factors of bacterial communities in a sediment profile of Bohai Sea. Sci. Nat. 2025, 112, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Su, Q.; Yang, S.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Liao, N.; Li, N.; Kang, B.; Huang, L. Sedimentary bacterial communities in subtropical Beibu Gulf: Assembly process and functional profile. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Pires, A.; Dias, G.M.; de Oliveira Mariano, D.C.; Akamine, R.N.; de Albuquerque, A.C.C.; Groposo, C.; de Figueiredo Vilela, L.; Neves, B.C. Molecular diversity and abundance of the microbial community associated to an offshore oil field on the southeast of Brazil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 160, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, A.F.; Chien, D.M.; Polz, M.F. Associations and dynamics of Vibrionaceae in the environment, from the genus to the population level. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.N.; Flowers, A.R.; Noriea, N.F., III; Zimmerman, A.M.; Bowers, J.C.; DePaola, A.; Grimes, D. Relationships between environmental factors and pathogenic Vibrios in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7076–7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beer, D.; Wenzhöfer, F.; Ferdelman, T.G.; Boehme, S.E.; Huettel, M.; van Beusekom, J.E.E.; Böttcher, M.E.; Musat, N.; Dubilier, N. Transport and mineralization rates in North Sea sandy intertidal sediments, Sylt-Rømø Basin, Wadden Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2005, 50, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; He, H.; Wu, H.; Zuo, W.; He, D. Responses of the rhizosphere bacterial community in acidic crop soil to pH: Changes in diversity, composition, interaction, and function. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessitsch, A.; Weilharter, A.; Gerzabek, M.H.; Kirchmann, H.; Kandeler, E. Microbial Population Structures in Soil Particle Size Fractions of a Long-Term Fertilizer Field Experiment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4215–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Point | PH | TP Concentration (mg/g) | TOC Concentration (mg/g) | TN Concentration (mg/g) | Particle Size (µm) | Sulphide (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 7.34 | 0.506 | 6.5 | 1.659 | 118 | 0.00028 |

| S2 | 7.3 | 0.489 | 5.6 | 1.414 | 120 | 0.00092 |

| S3 | 7.38 | 0.448 | 4.8 | 1.120 | 123 | 0.00047 |

| S4 | 7.26 | 0.393 | 4.7 | 1.182 | 116 | 0.00045 |

| S5 | 7.36 | 0.425 | 6.0 | 1.261 | 127 | 0.00011 |

| S6 | 7.68 | 0.533 | 9.6 | 0.974 | 135 | 0.00079 |

| S7 | 7.64 | 0.529 | 6.9 | 1.458 | 150 | 0.00029 |

| S8 | 7.7 | 0.347 | 9.8 | 1.168 | 125 | 0.00086 |

| S9 | 7.63 | 0.358 | 5.0 | 1.187 | 130 | 0.00091 |

| S10 | 7.68 | 0.453 | 4.0 | 1.095 | 110 | 0.00099 |

| S11 | 7.64 | 0.349 | 3.4 | 0.865 | 133 | 0.00032 |

| S12 | 7.7 | 0.265 | 6.7 | 1.631 | 94 | 0.00041 |

| Sampling Point | Concentration (mg/L) | Concentration (mg/L) | Concentration (mg/L) | COD (mg/L) | Phosphate (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.1206 | 0.412 | 0.0069 | 1.01 | 0.007 |

| S2 | 0.1150 | 0.398 | 0.0059 | 1.31 | 0.006 |

| S3 | 0.0935 | 0.363 | 0.0035 | 1.34 | 0.011 |

| S4 | 0.0834 | 0.395 | 0.0045 | 0.82 | 0.007 |

| S5 | 0.0569 | 0.454 | 0.0105 | 0.87 | 0.008 |

| S6 | 0.0627 | 0.195 | 0.0020 | 0.91 | 0.007 |

| S7 | 0.0318 | 0.301 | 0.0029 | 0.79 | 0.007 |

| S8 | 0.0183 | 0.220 | 0.0023 | 0.85 | 0.009 |

| S9 | 0.0802 | 0.343 | 0.0050 | 1.02 | 0.01 |

| S10 | 0.0950 | 0.413 | 0.0050 | 1.05 | 0.015 |

| S11 | 0.0359 | 0.301 | 0.0055 | 1.04 | 0.007 |

| S12 | 0.0613 | 0.305 | 0.0059 | 0.97 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Xin, C.; Han, S.; Hu, H.; Liu, L.; Bao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Jiang, M. Characteristics of Microbial Communities in Sediments from Culture Areas of Meretrix meretrix. Diversity 2025, 17, 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120848

Wang F, Zhu Y, Xin C, Han S, Hu H, Liu L, Bao J, Zhang X, Li L, Jiang M. Characteristics of Microbial Communities in Sediments from Culture Areas of Meretrix meretrix. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):848. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120848

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fengbiao, Yue Zhu, Chaozhong Xin, Shuai Han, Haopeng Hu, Longyu Liu, Jinmeng Bao, Xuan Zhang, Lei Li, and Mei Jiang. 2025. "Characteristics of Microbial Communities in Sediments from Culture Areas of Meretrix meretrix" Diversity 17, no. 12: 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120848

APA StyleWang, F., Zhu, Y., Xin, C., Han, S., Hu, H., Liu, L., Bao, J., Zhang, X., Li, L., & Jiang, M. (2025). Characteristics of Microbial Communities in Sediments from Culture Areas of Meretrix meretrix. Diversity, 17(12), 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120848