1. Introduction

The swimming crab,

Portunus trituberculatus, is a commercially important decapod crustacean widely distributed in coastal waters of East Asia, supporting one of the most valuable crab fisheries in China [

1]. In 2006, the aquaculture production of

P.

trituberculatus surged to 83,465 tons, establishing it as one of China’s most important commercial crab species [

2].

P.

trituberculatus has several developmental stages, including zygote, zoea, megalopa, juvenile crab, subadult crab and adult crab. Throughout these stages, particularly after settlement to the benthic environment,

P. trituberculatus is obligated to undergo successive molts to grow. The molting process represents a period of extreme vulnerability, as individuals with a soft new exoskeleton are highly susceptible to cannibalism and predation [

3,

4]. The availability and type of bottom substrate play a critical role in mitigating this risk. The absence of suitable unconsolidated substrates, such as sand or muddy sand, which allow for burial and concealment, can lead to increased aggressive encounters and mortality, especially in high-density conditions. Substratum preference is shown to be the most important factor influencing crab distribution. Among the various factors regulating decapod recruitment, postlarval settlement behavior plays a pivotal role in the selection of appropriate substrates that provide shelter and feeding opportunities during early benthic life stages. Postlarvae actively select suitable substrates prior to metamorphosis into the first juvenile instar, and in the absence of appropriate settlement conditions, some species are capable of delaying metamorphosis [

5,

6]. In certain taxa, such as

Petrolisthes cinctipes [

5] and

Uca pugilator [

7], settlement tends to occur on substrates already inhabited by adult conspecifics. Settlement can also be mediated by chemical cues, as observed in the blue crab

Callinectes sapidus [

8].

In general, postlarvae of many decapod species exhibit strong preferences for structurally complex habitats that enhance their survival and growth [

9,

10]. For example, glaucothoe of both the blue king crab (

Paralithodes platypus) and red king crab (

Paralithodes camtschaticus) actively select complex substrates such as cobble, shell hash, and gravel over bare sand, with these preferences often shifting as crabs grow and their shelter requirements change [

9,

11]. Similarly, juvenile Dungeness crab (

Cancer magister) megalopae selectively settle in shell habitats that minimize predation risk [

12], while early benthic stages of the American lobster (

Homarus americanus) strongly prefer rocky or vegetated substrates for settlement [

13]. These substrate choices are closely linked to survival, as structurally complex habitats provide refuge from predators and reduce cannibalism [

14,

15]. In aquaculture settings, substrate type also significantly affects welfare and behavior. Recent research on

P. trituberculatus has demonstrated that the presence of sand substrate reduces territorial behavior and aggression, promotes natural burying behavior, and improves overall welfare in culture systems [

16]. Similar benefits of environmental enrichment through substrate provision have been observed in other crustacean species [

17,

18], highlighting the importance of matching aquaculture conditions to species-specific ecological requirements.

Despite the ecological and economic importance of

P. trituberculatus, quantitative studies on the substrate preferences of its early developmental stages remain limited. Previous research has focused primarily on larval development, reproductive biology, and aquaculture techniques [

19,

20], leaving a significant gap in our understanding of how juvenile and subadult crabs select and utilize different substrate types. Furthermore, diel patterns in substrate use, which are known to influence behavior in many portunid crabs, have not been thoroughly investigated in this species.

Understanding these preferences is crucial not only for predicting recruitment variability in wild populations but also for optimizing stocking strategies in aquaculture and stock enhancement programs [

21,

22]. This study therefore aimed to investigate the substrate selection behavior of early developmental stages of

P. trituberculatus under controlled laboratory conditions, with specific attention to preferences among different natural substrates and potential diel variations in substrate use. The results provide valuable insights for habitat-based management and conservation of this commercially important species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Collection and Substrate Source

All the experimental crabs were sourced from the Portunus trituberculatus aquaculture at the Qidong breeding base of the Shanghai Fisheries Research Institute, with all larvae obtained from artificial breeding. The substrate type used at the breeding base is sandy substrate. A total of 300 subadult crabs (mean body weight: 22.6 ± 1.23 g) and 400 juvenile crabs (mean body weight: 0.28 ± 0.12 g) were used. Preliminary experiments indicated no significant difference in substrate preference between males and females; therefore, all formal experiments were conducted using a 1:1 female-to-male ratio. After collection, all crabs were acclimated indoors for one week to adapt to laboratory conditions. During the acclimation period, the crabs were fed once every evening. The salinity was maintained at 28‰, and the rearing water temperature was approximately 24 °C. Juvenile crabs were fed frozen Artemia at 2–3% of their body weight, whereas subadult crabs were fed live Manila clams (Ruditapes philippinarum) at 3–5% of their body weight. After one week of acclimation, only individuals with intact appendages and vigorous activity were selected for subsequent experiments.

The four substrates used in the experiment were collected from the Yangtze River Estuary. Four substrate types were prepared: mud, muddy sand (a 1:1 mixture of mud and fine sand), fine sand (particle size 0.2–0.5 mm), and medium sand (particle size 0.5–1.0 mm). Sand samples were sieved to obtain the desired grain size, thoroughly rinsed, and air-dried prior to use to avoid water turbidity during trials. Mud samples were air-dried and ground into fine powder before use. During the experiments, the substrate depth for both juvenile and subadult crabs was maintained at 5 cm to ensure that individuals could completely bury themselves within the sediment.

2.2. Experimental Design and Procedure

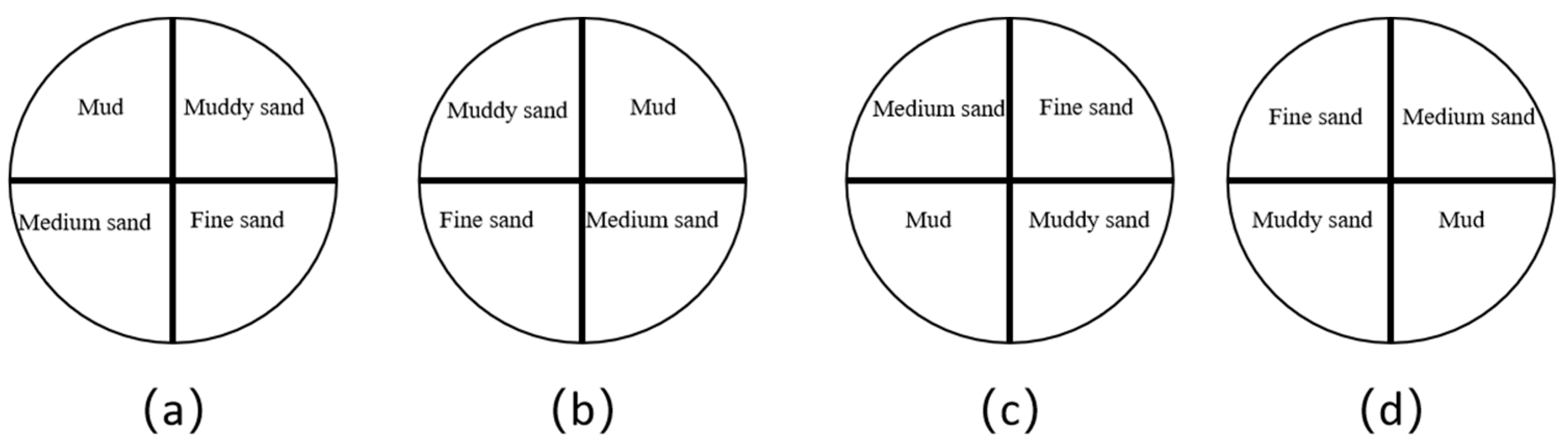

Different types of experimental apparatus were used for the two developmental stage. For juvenile crabs, experiments were conducted in red circular basins with a diameter of 60 cm. Each basin was evenly divided into four compartments using 5 cm high acrylic partitions, with a different substrate type placed in each compartment. For subadult crabs, experiments were carried out in cylindrical fiberglass tanks with a diameter of 120 cm, following the same compartmental design and operational procedures as used for juveniles. The layout of the apparatus is shown in

Figure 1.

Within each piece of apparatus, four types of substrates—mud, muddy sand, fine sand, and medium sand—were placed in the four compartments. To eliminate positional bias in substrate selection, four different substrate arrangement patterns were applied so that each substrate type occupied each position across trials. To minimize external interference, the entire testing area was enclosed with opaque curtains. Two infrared cameras were mounted above each piece of apparatus to ensure full visual coverage of the experimental area, allowing continuous monitoring and video recording of crab behavior under infrared illumination.

The substrate preference experiments were conducted in two forms: individual trials and group trials. Preliminary observations showed that when experimental crabs were placed in the apparatus, their activity levels markedly decreased after approximately 15 min, and stress-related behaviors such as escape attempts or rapid swimming ceased.

For individual experiments, a single crab was placed into the apparatus and allowed to acclimate for 15 min. Subsequently, its behavior was continuously recorded for 5 min using infrared cameras. The time spent on each substrate type was quantified from the video footage. For group experiments, ten crabs were released into each piece of apparatus simultaneously. Observations were conducted once every hour for a total of 8 h, and the number of crabs present on each substrate type during each observation was recorded.

The four substrate types used in both experiments were: mud, muddy sand (a 1:1 mixture of mud and fine sand), fine sand (particle size 0.2–0.5 mm), and medium sand (particle size 0.5–1.0 mm). Prior to each trial, crabs were gently removed from the acclimation tanks, the surface moisture on their carapaces was wiped off with a soft towel, and they were then carefully introduced into the experimental apparatus. Because P. trituberculatus exhibits a nocturnal lifestyle—remaining buried or inactive during the day and becoming active at night—both individual and group experiments were conducted separately during daytime and nighttime to evaluate whether substrate preference differed between light periods.

For subadult crabs, ten individuals were tested in each individual experiment (one per trial), with three replicates per group and four experimental groups in total. In group experiments, ten crabs were placed per tank, and their distribution among substrates was recorded once every hour for a total of eight observations. Each experiment included three replicates. Water temperature in the experimental tanks was maintained within ±1 °C of that in the acclimation tanks.

To avoid positional bias, the placement of the four substrate types within the apparatus was randomized among trials. Furthermore, the release positions of the experimental crabs were alternated between trials to prevent any location-based preference that might affect behavioral outcomes (

Figure 1). The experimental procedures for juvenile crabs were similar to those for subadults, with minor modifications. Preliminary observations showed that juvenile crabs tended to bury themselves within the substrate. Therefore, in addition to recording the time spent and frequency of occurrence on each substrate, their habitat states were also categorized as buried (carapace partially or fully submerged in the substrate) or exposed (carapace visible above the substrate surface).

Because juveniles exhibited stronger mobility, the acclimation period was extended to 20 min. For juvenile individual trials, one crab was placed in the apparatus at a time; each group included five crabs, with three replicates, and four experimental groups were conducted in total. Burrowing behavior of juveniles could not be accurately recorded by camera, and was therefore documented manually during on-site observation. For juvenile group experiments, both daytime and nighttime observations were performed five times each.

Due to the very small size of early-stage juveniles, camera-based observation was difficult and visual counting errors were considerable. Therefore, only group experiments were conducted for these early juveniles, with 20 crabs per group. Their habitat states were recorded once during the day and once at night following the same classification criteria as for subadults.

Figure 1.

Experimental apparatus used for different early developmental stages of Portunus trituberculatus. To eliminate potential bias caused by positional preference, four different substrate placement arrangements (a–d) were used to ensure that the crabs’ substrate selection was not influenced by their spatial location.

Figure 1.

Experimental apparatus used for different early developmental stages of Portunus trituberculatus. To eliminate potential bias caused by positional preference, four different substrate placement arrangements (a–d) were used to ensure that the crabs’ substrate selection was not influenced by their spatial location.

2.3. Data Acquisition and Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to determine the significant differences in preference for substrate of P. trituberculatus (p < 0.05). Duncan’s multiple range test was performed to analyze the differences between substrate preferences. The significance of the differences between groups were tested by an independent samples t-test. All data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and these results are presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation of the mean).

4. Discussion

The distribution and survival of early benthic stages of decapod crustaceans are profoundly influenced by substrate characteristics, with grain size and structural complexity being critical factors [

23]. The present study demonstrates that this principle applies strongly to the commercially important swimming crab

P.

trituberculatus, whose early developmental stages exhibit clear and ontogenetically variable substrate preferences.

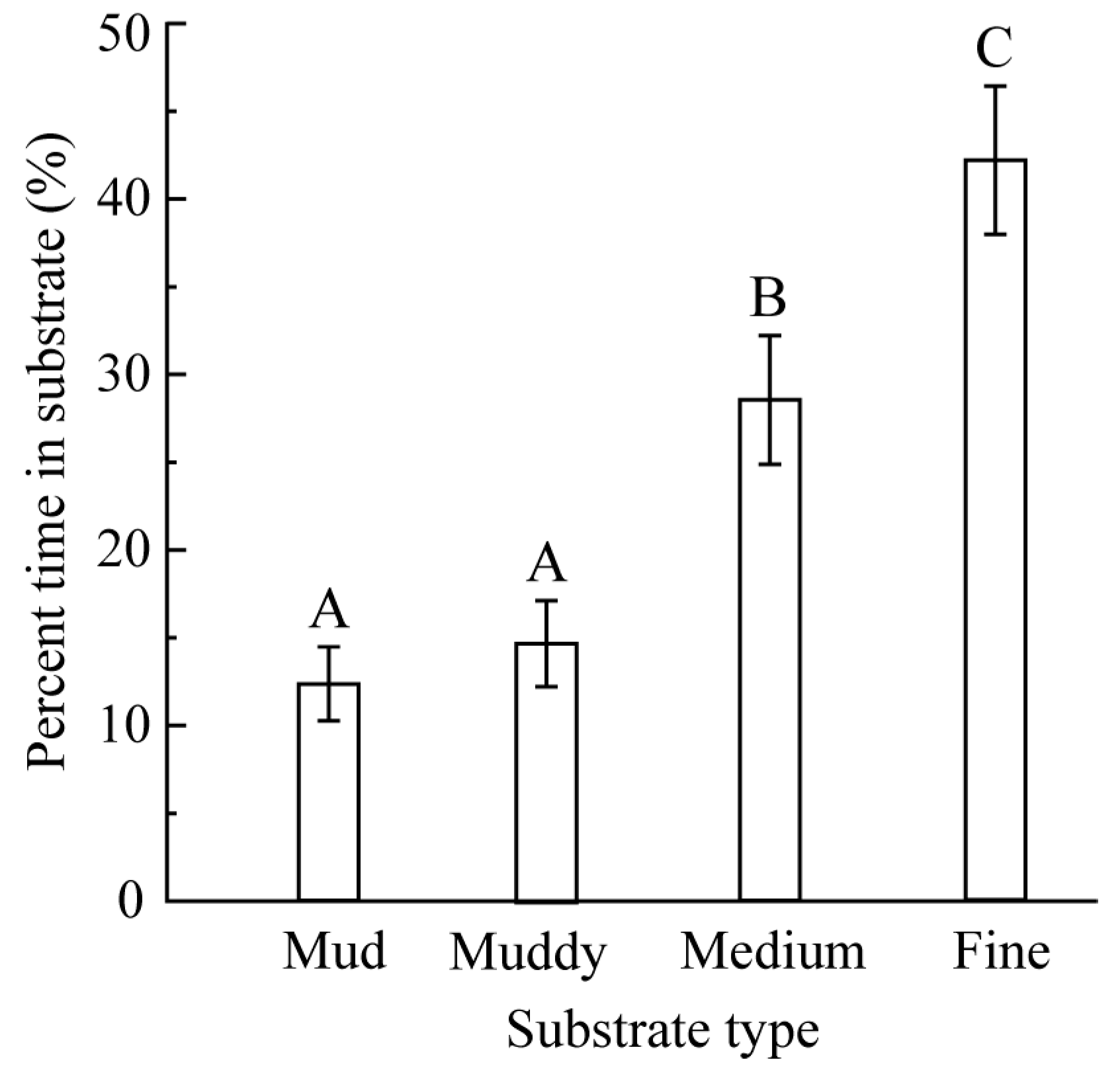

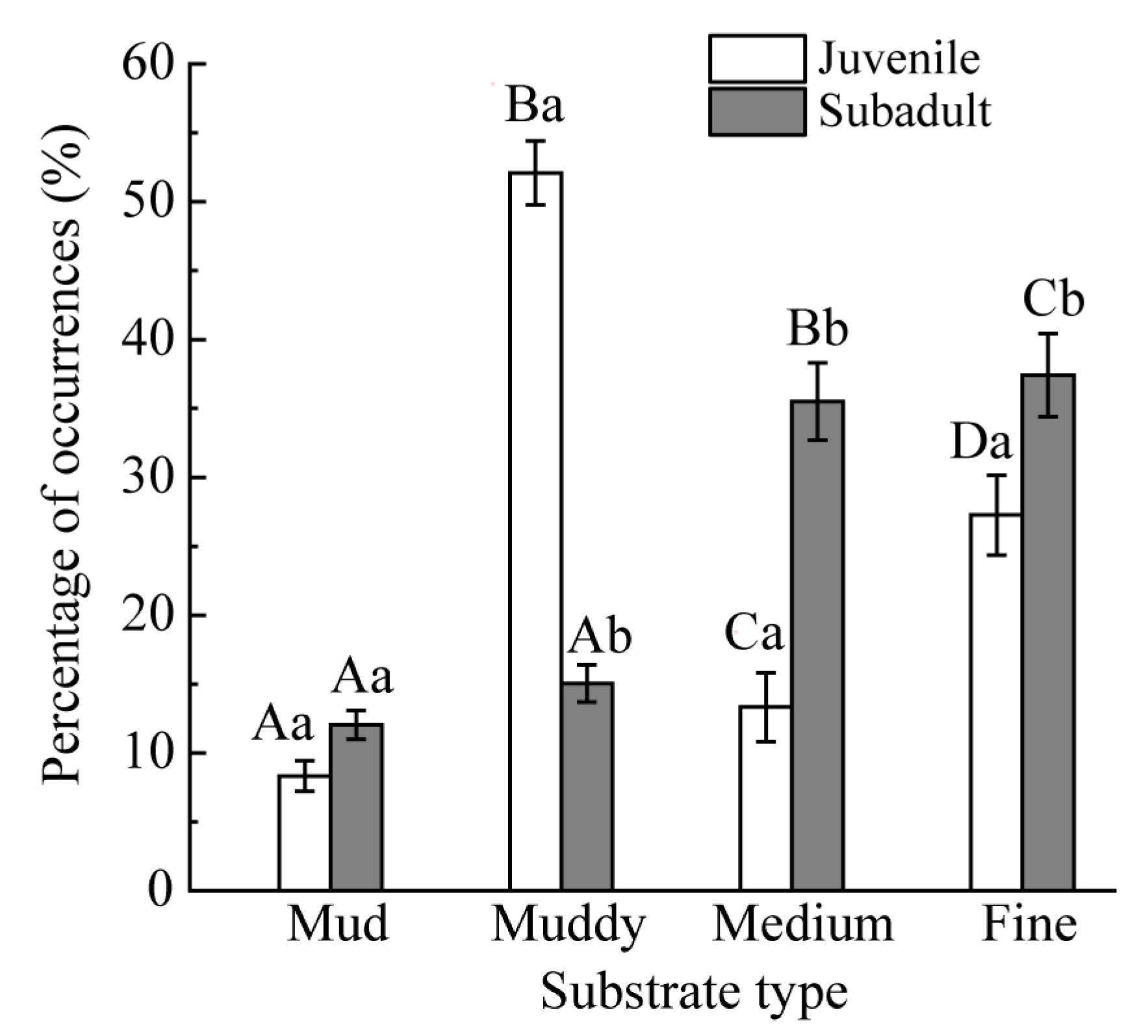

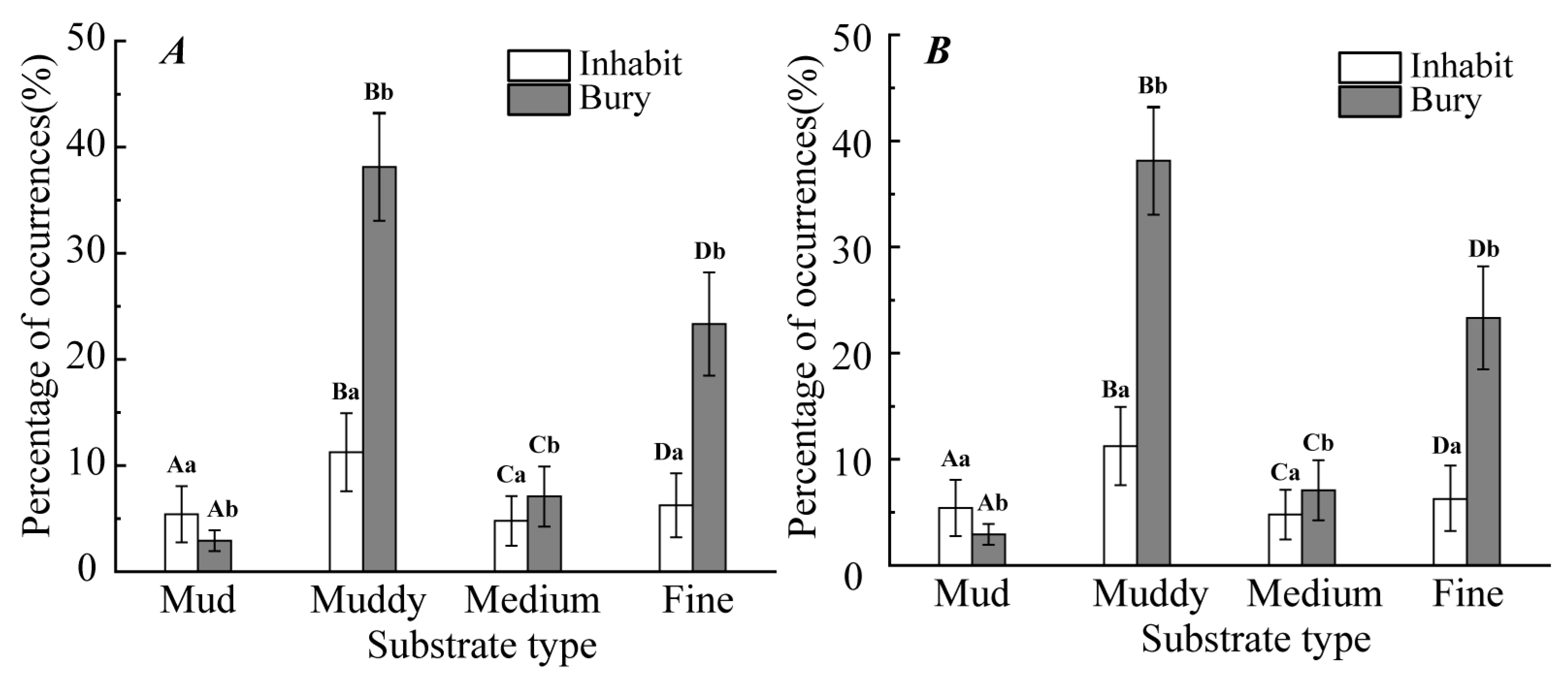

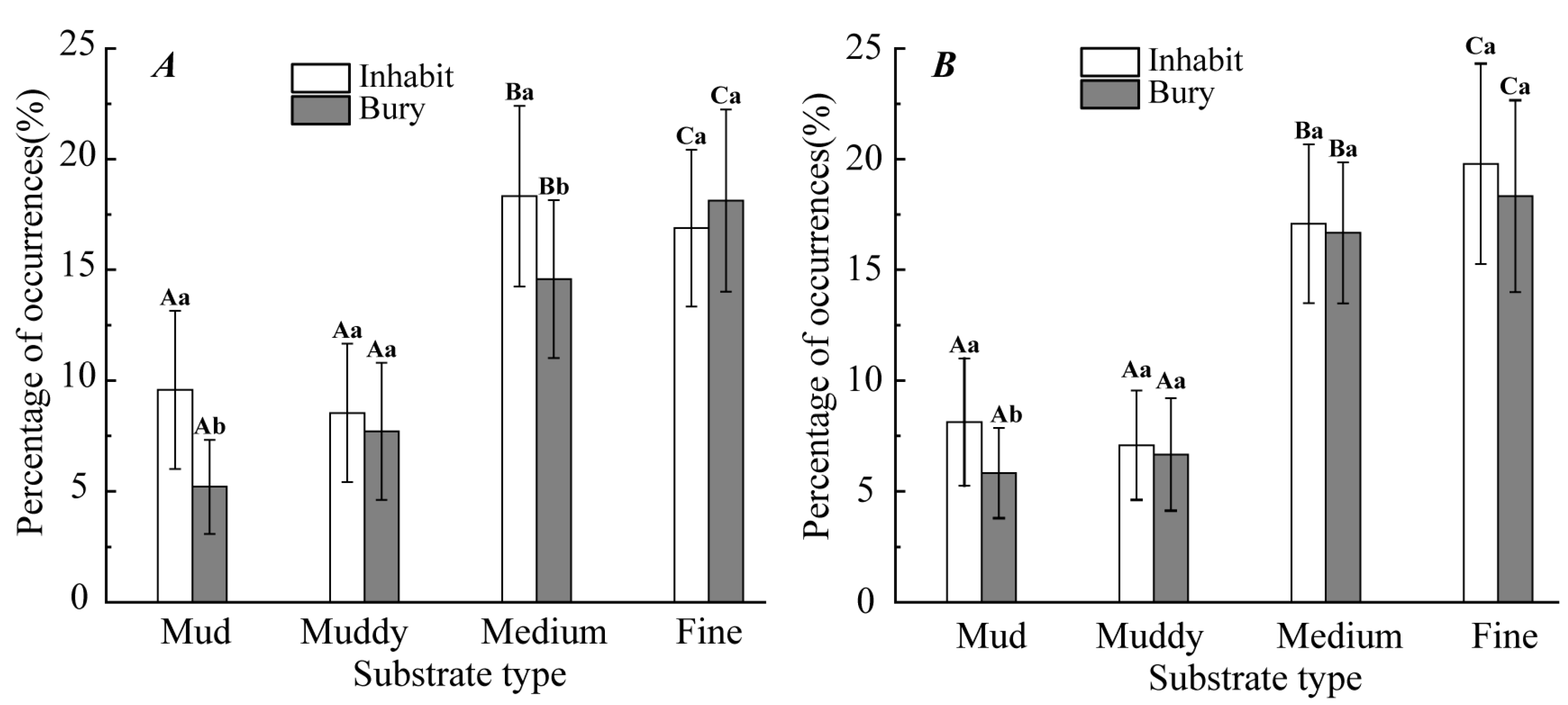

Our results indicate that juvenile crabs significantly preferred muddy-sand substrates, whereas subadults showed a stronger affinity for fine sand. This preference for finer sediments in early life stages is likely an adaptive behavior to minimize predation risk and cannibalism, two major sources of mortality for early juvenile portunids [

24]. The cohesive nature of muddy sand facilitates effective burial, providing crucial concealment during the vulnerable molting period [

15]. Similar substrate selection behaviors have been documented across various crab taxa. For instance, megalopae of the blue crab

Callinectes sapidus actively select structurally complex substrates like live seagrass (

Zostera marina), which offer both structural refuge and chemical settlement cues [

10]. This reliance on chemical signals for habitat selection is well established in decapod crustaceans, where specific water-soluble compounds from optimal nursery habitats can actively trigger settlement and metamorphosis in competent larvae [

25]. Although not explicitly tested here, similar mechanisms may influence

P. trituberculatus settlement, particularly in muddy sand habitats rich in organic matter and microbial activity. Due to the higher proportion of fine particulate matter in muddy sand sediments, they are capable of adsorbing and retaining more organic matter, thereby providing abundant carbon sources for microorganisms and promoting their metabolic activity [

26].

The ontogenetic shift in substrate preference observed in our study, from muddy sand in juveniles to fine sand in subadults, parallels patterns documented in other crab species. For example, blue king crab (

Paralithodes platypus) glaucothoe initially settle on various complex substrates but redistribute to habitats with larger interstitial spaces after molting to the first crab stage [

11]. This behavioral shift is likely driven by changing ecological requirements, as larger crabs may favor substrates that support different foraging strategies and shelter needs. In both species, the preference for more complex substrates in earlier life stages, followed by a shift to substrates with larger interstitial spaces in later stages, can be interpreted as a response to the evolving physical and ecological demands of the crabs. For juvenile blue king crabs, the need for more sheltered environments likely reflects a higher vulnerability to predation and a reliance on complex habitats for protection. Similarly, for juvenile

P. trituberculatus, muddy sand habitats may provide increased organic matter and microbial activity, offering essential food sources and shelter. As the crabs grow, they may shift to finer substrates, such as fine sand, where their larger size allows them to forage more efficiently and find adequate shelter. These shifts in substrate preference highlight the role of substrate type in supporting the different ecological needs of juvenile and subadult crabs, emphasizing the importance of suitable habitat management to ensure the survival and growth of these species. The critical role of specific substrate types in supporting juvenile demersal species underscores the need for habitat-based fisheries management approaches [

14].

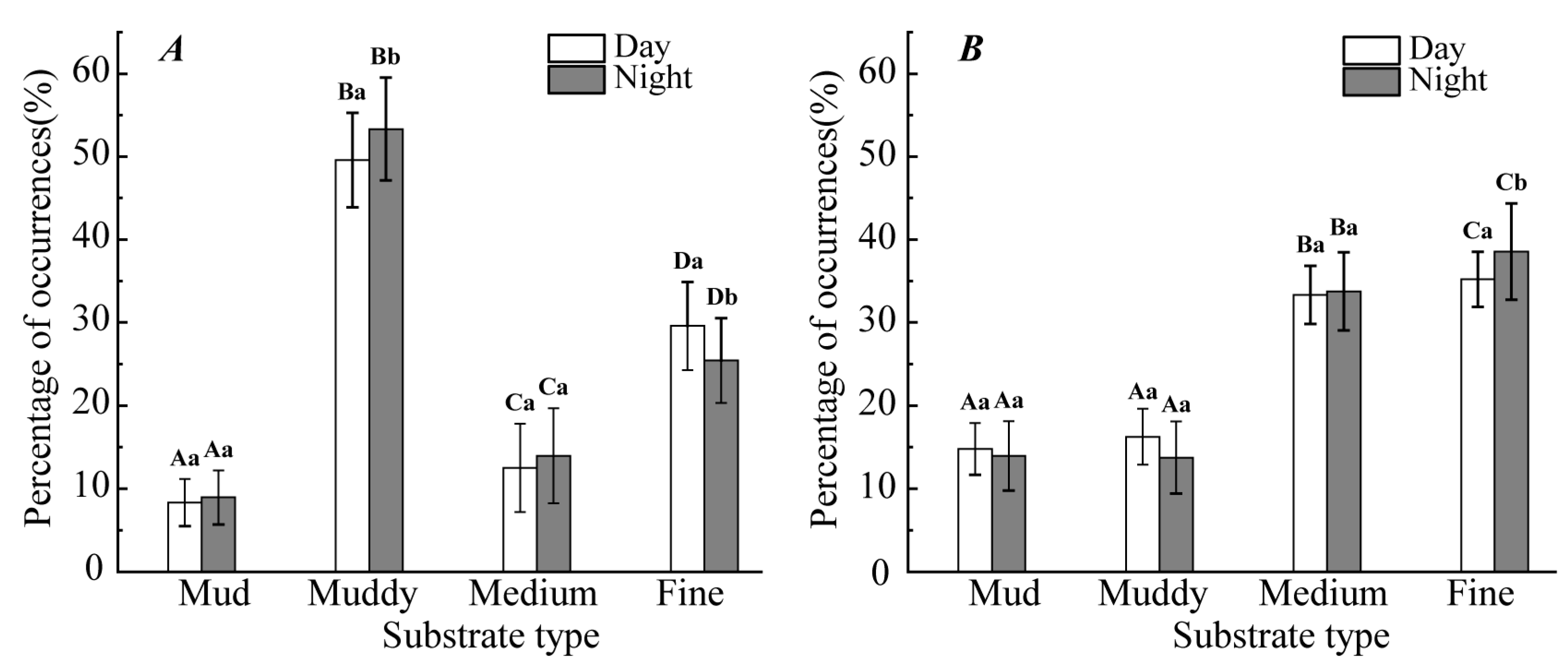

A key finding of our study is the significant diel variation in substrate use, with both juvenile and subadult crabs altering their substrate preferences between day and night. These behavioral rhythms align with the well-documented nocturnal activity patterns in portunids [

27], which are often governed by their endogenous circadian clocks, which function to reduce exposure to visual predators and potentially minimize agonistic encounters with conspecifics [

12]. Recent field studies on

P. trituberculatus have confirmed a strong correlation between juvenile abundance and sediment characteristics in natural estuarine environments [

16], validating the ecological relevance of our laboratory findings.

The differential burying behavior observed further illuminates the functional significance of substrate selection. The high burial frequency of juveniles in muddy sand contrasts with the lower burial rates and more surface-oriented behavior of subadults, reflecting an ontogenetic trade-off between predator avoidance and foraging efficiency. This pattern of increasing mobility and decreasing crypticity with growth has been documented in other portunid species [

28]. From an applied perspective, the welfare benefits of providing suitable substrates, including reduced aggression and the promotion of natural behaviors, have been confirmed in aquaculture settings for various crustaceans [

18].

The sympatric coexistence of multiple crab species frequently involves fine-scale niche partitioning mediated by substrate preference, as documented in diverse intertidal communities [

29]. While our study focuses on intraspecific (ontogenetic) shifts in substrate preference in

P.

trituberculatus, it is relevant to note that such ontogenetic shifts could indirectly reduce the potential for interspecific competition, especially in shared nursery habitats. By partitioning substrates according to developmental stages,

P. trituberculatus may minimize overlap with other co-occurring species that favor similar substrate types, thereby reducing competitive interactions. Moreover, the fundamental importance of chronobiological adaptations in marine species further explains the observed diel patterns in behavior [

30].

In conclusion, the stage-specific and diurnally modulated substrate preferences of early-life

P.

trituberculatus revealed in this study are critical determinants of their distribution and survival. These findings have direct and profound implications for habitat-based management. The preservation and restoration of specific nursery habitats, such as muddy sand and fine sand bottoms, are not merely a conservation goal but an economic imperative, as the value of such structured habitats for fishery production is well-established [

31]. Our results underscore that effective resource management must account for ontogenetic shifts in habitat use, as the ecological role of a habitat in supporting a fishery is fundamentally linked to its capacity to sustain critical life stages [

32]. Furthermore, the observed behaviors highlight the necessity of incorporating habitat quality metrics into stock assessments. Ignoring these fine-scale habitat requirements can lead to the degradation of essential benthic ecosystems and the services they provide, ultimately undermining fishery sustainability [

33]. Whether in indoor aquaculture or stock enhancement and release, it is essential to provide appropriate substrates for

P.

trituberculatus at each developmental stage. This can significantly improve their survival and molting rates. Such measures are crucial for maintaining population resources and ensuring the sustainability of fisheries.

In aquaculture and stock enhancement contexts, these findings indicate a need for the strategic provision of appropriate substrates. Such environmental enrichment can mitigate density-dependent stressors; as demonstrated in the swimming crab (

P.

trituberculatus), the addition of sand substrate significantly reduced aggression and cannibalism, thereby improving survival and yield in culture tanks. Ultimately, integrating this understanding of fine-scale habitat requirements into coastal spatial planning and restoration is essential. The critical role of sediment grain size in determining benthic distribution is a fundamental principle in marine ecology, well-established for a wide range of crab species [

34]. This approach is supported by the growing recognition that for many crabs, specific substrate preferences during early life history are a key behavioral mechanism driving observed distribution patterns in the field [

35]. Moreover, the active restoration of structurally complex seabed habitats has been demonstrated to enhance the production of commercial crustaceans. This is concretely evidenced by studies on the blue crab (

Callinectes sapidus), which show that restored seagrass meadows, a complex biogenic substrate, function as essential nursery habitats that significantly increase juvenile survival and recruitment to fisheries [

36]. In the case of

P.

trituberculatus, understanding the specific substrate preferences at various life stages is crucial for both aquaculture and stock enhancement. By providing substrates that match the crabs’ natural behavior, such as the preference for muddy sand during early stages and fine sand in later stages, survival rates can be improved, and stress-induced mortality can be minimized. This tailored approach not only enhances the efficiency of culture systems but also contributes to the long-term sustainability of

P. trituberculatus populations in the wild.

5. Conclusions

As a key component of habitats, substrate is a crucial subject in the study of aquatic animal habitats. Due to its migratory behavior, the swimming crab (P. trituberculatus) does not have a fixed living area in water. It is mainly distributed in inner bay waters with intertidal beaches. In this study, the habitat preference of swimming crabs for substrate sediments was investigated through controlled experiments conducted in the laboratory. In summary, the results showed significant differences in the substrate selection of P. trituberculatus at different developmental stages: (1) Juvenile crabs had an obvious preference for muddy sand, while subadult crabs preferred fine sand. (2) Both juvenile and subadult crabs exhibited concealment behavior within the substrate. Juveniles displayed such behavior consistently during both daytime and night, whereas subadults showed it predominantly during daytime. This diel variation is likely related to the species’ predation and predation-avoidance adaptations.

In summary, understanding the substrate preferences of P. trituberculatus has important implications for aquaculture, stock enhancement, and ecological restoration. The results of this study reveal that juvenile crabs exhibit the strongest preference for muddy-sand substrates, juvenile crabs also favored muddy sand, while subadults preferred fine sand. These ontogenetic shifts in substrate preference suggest that providing suitable substrates at different developmental stages can greatly improve habitat suitability and survival efficiency. In aquaculture systems, optimizing substrate composition according to these preferences can reduce stress and cannibalism, promote normal growth, and increase overall survival rates. For stock enhancement and release programs, selecting release sites that match the preferred substrates of subadult and juvenile crabs—especially muddy-sand and fine-sand areas—can enhance post-release settlement and adaptation. In ecological restoration, maintaining or rehabilitating coastal zones with appropriate muddy-sand and fine-sand habitats can facilitate natural recruitment and population recovery of this commercially important species. Therefore, integrating substrate characteristics into aquaculture management, release strategies, and habitat restoration planning is essential for the sustainable development and conservation of P. trituberculatus populations. In order to effectively increase resources, crabs at different developmental stages should be raised in areas with different substrates (mud, muddy sand, fine sand, and medium sand) according to their preference for substrates to improve the survival rate.