Plant Diversity Patterns and Their Determinants Across a North-Edge Tropical Area in Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

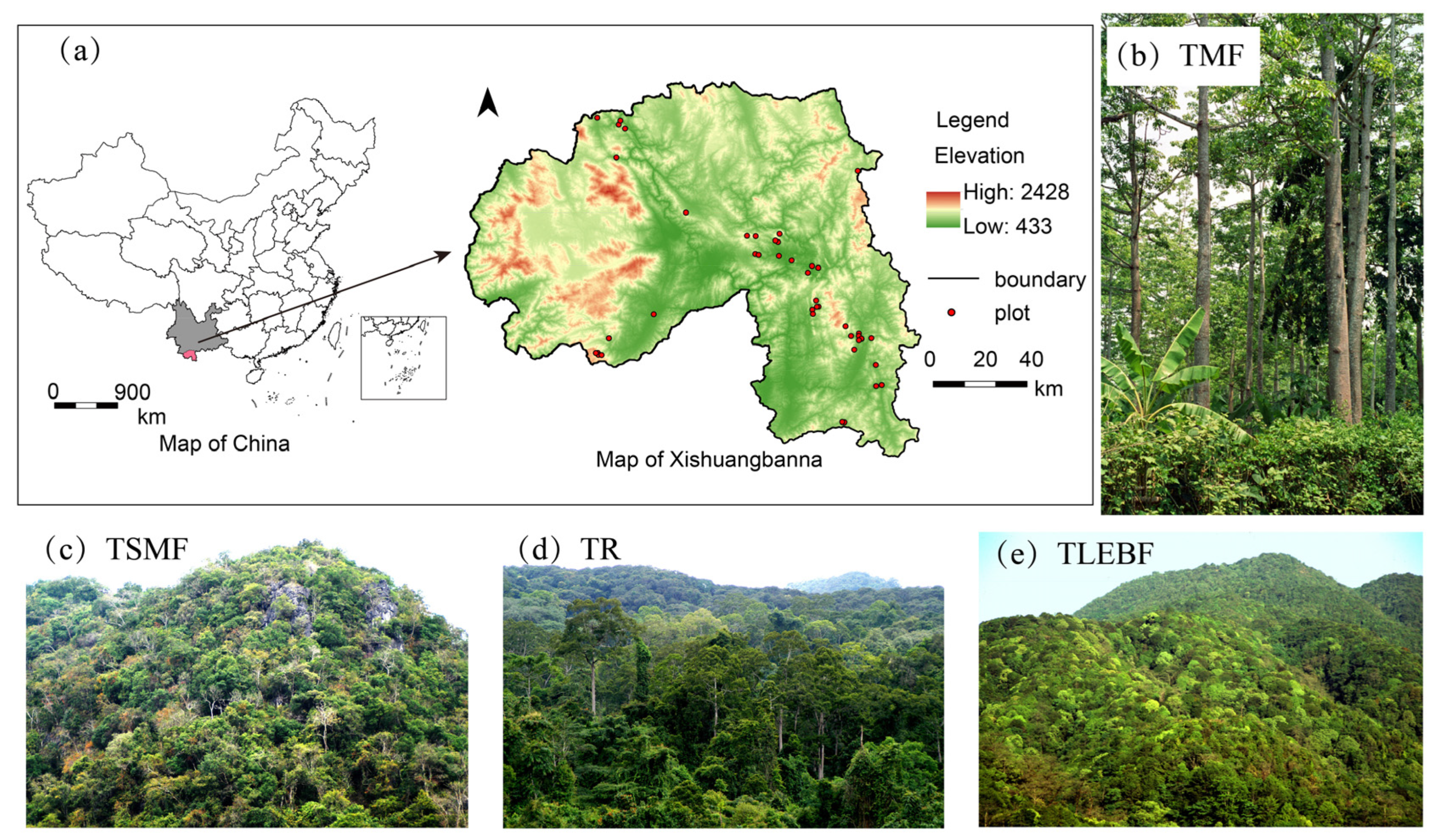

2.1. Study Objects

2.2. Environment Data Source and Pre-Treatment

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Difference in Biodiversity Across Forest Types

2.3.2. Discriminant Analysis of Environmental Determinants

2.3.3. Difference in the Plant Species Composition Across Four Forest Types

2.3.4. Influence of Environmental Variables on Diversity for Forests

3. Results

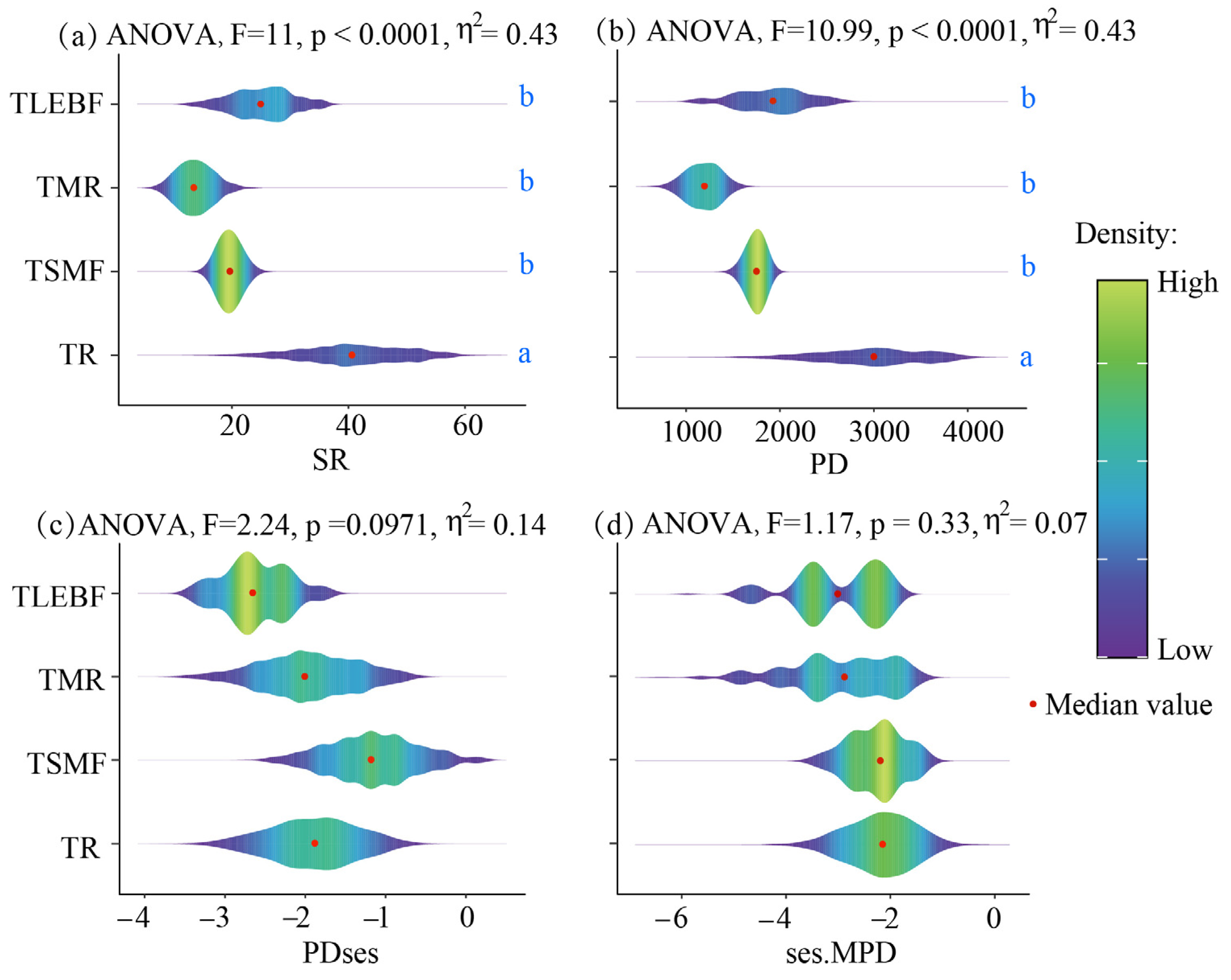

3.1. Differences in Biodiversity Across Four Forest Types

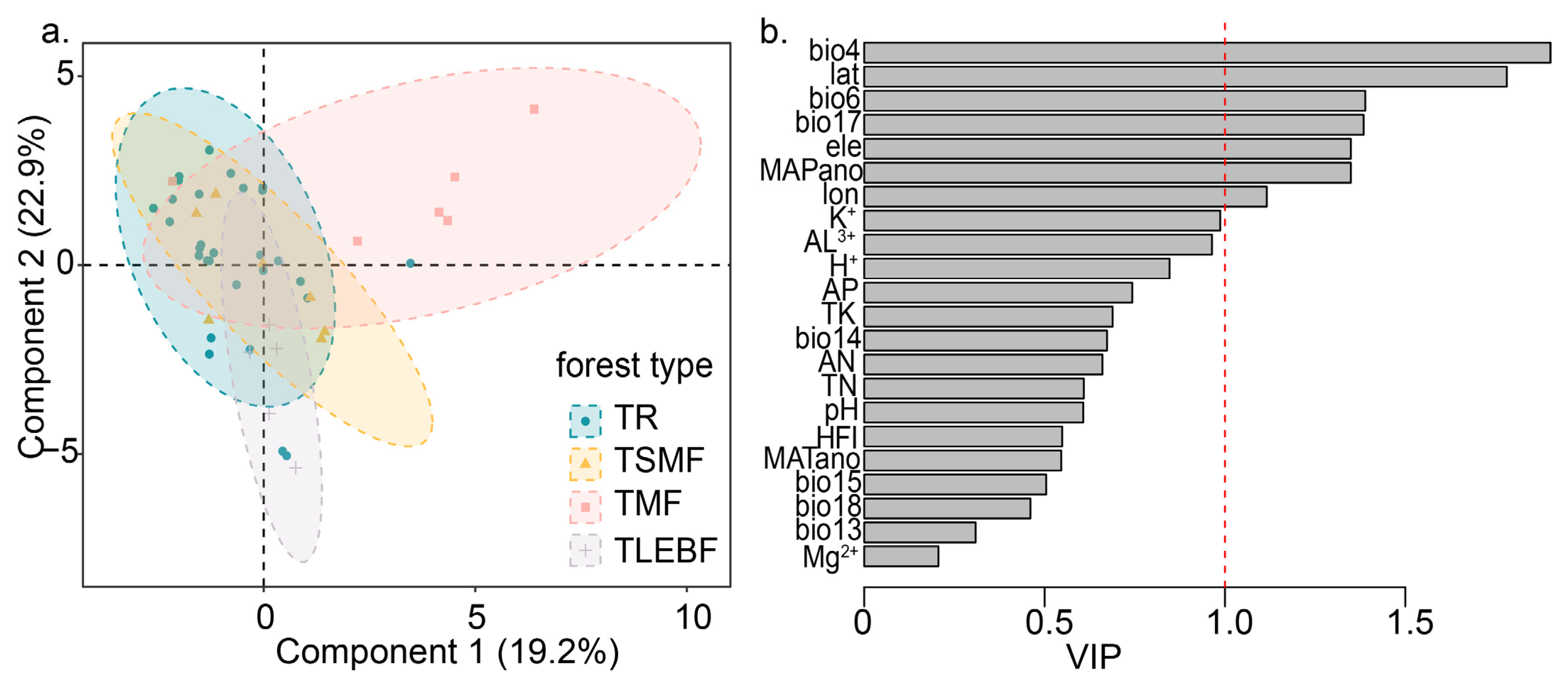

3.2. Difference in Environmental Determinants Across Four Forest Types

3.3. Difference in Community Composition

3.4. Factors Influencing the Diversity of Forests

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution, Diversity and Environmental Influences of the Forest Types in Xishuangbanna

4.2. Implications for Biodiversity Conservation in Xishuangbanna Area

4.2.1. Conservation Priority in Xishuangbanna

4.2.2. TR and TSMF Under Climate Change in Xishuangbanna

4.2.3. Conservation Suggestion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TR | Tropical forests |

| TLBEF | Tropical lower-montane evergreen broadleaf forests |

| TSMF | Tropical seasonal moist forests |

| TMR | Tropical monsoon forests |

| SR | Species richness |

| PD | Phylogenetic diversity |

| PDses | Standardized phylogenetic diversity |

| ses.MPD | Standardized mean phylogenetic distance |

| VIP | Variable importance in the projection |

| PLS-DA | Partial least-squares discriminant analysis |

| NMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination |

| PERMANOVA | permutational multivariate analysis of variance |

| TCH | Tropical niche conservatism hypothesis |

References

- Yan, P.; Fernandez-Martinez, M.; Van Meerbeek, K.; Yu, G.; Migliavacca, M.; He, N. The essential role of biodiversity in the key axes of ecosystem function. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 4569–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Qiao, Y.P.; Wang, L.J.; Zhang, J.C. Terrain gradient variations in ecosystem services of different vegetation types in mountainous regions: Vegetation resource conservation and sustainable development. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 482, 118856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.A.; McBride, M.F.; Bode, M.; Possingham, H.P. Prioritizing global conservation efforts. Nature 2006, 440, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margules, C.R.; Pressey, R.L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 2000, 405, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, M. Phylogenetic diversity in conservation: A brief history, critical overview, and challenges to progress. Camb. Prism. Extinction 2023, 1, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, F.; Grenyer, R.; Rouget, M.; Davies, T.J.; Cowling, R.M.; Faith, D.P.; Balmford, A.; Manning, J.C.; Proches, S.; van der Bank, M.; et al. Preserving the evolutionary potential of floras in biodiversity hotspots. Nature 2007, 445, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.R.; Davies, T.; Harish, S.M.; Dar, J.A.; Kothandaraman, S.; Ray, T.; Malasiya, D.; Dayanandan, S.; Khan, M.L. Phylogenetic community patterns suggest Central Indian tropical dry forests are structured by montane climate refuges. Divers. Distrib. 2023, 29, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Qian, S.; Zhang, J.; Kessler, M. Effects of climate and environmental heterogeneity on the phylogenetic structure of regional angiosperm floras worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Jiang, L. Phylogenetic community ecology: Integrating community ecology and evolutionary biology. J. Plant Ecol. 2014, 7, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.O.; Ackerly, D.D.; McPeek, M.A.; Donoghue, M.J. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Regalado, C.N.; Lavariega, M.C.; Briones-Salas, M. Spatial Patterns of Taxonomic, Functional, and Phylogenetic Diversity of Mammals in Southern Mexico. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockridge, E.G.; Bradford, E.; Angier, K.I.W.; Youd, B.H.; McGill, E.B.M.; Ngouma, S.Y.; Ognangue, R.L.; Gibbon, G.E.M.; Davies, A.B. Spatial ecology, biodiversity, and abiotic determinants of Congo’s bai ecosystem. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 105, e4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassum, B.W.; Kallio, A.; Tromborg, E.; Rannestad, M.M. Vegetation density and altitude determine the supply of dry Afromotane forest ecosystem sevices: Evidence from Ehiopia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 552, 121561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewitt, D. Vegetation type conservation targets, status and level of protection in KwaZulu-Natal in 2016. Bothalia 2018, 48, a2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.; Fayolle, A.; Godlee, J.L.; Gorel, A.P.; Harris, D.J.; Dexter, K.G. Patterns and drivers of phylogenetic beta diversity in the forests and savannas of Africa. J. Biogeogr. 2025, 52, e15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.S.; Monteiro, F.K.; Rodrigues, E.; Gomes, D.R.F.L.; Medeiros, M.C.; Lopes, S.F. Phylogenetic diversity and conservation challenges in Brejos de Altitude: Assessing threatened areas of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Kraft, N.J.; Yu, H.; Li, H. Seed plant phylogenetic diversity and species richness in conservation planning within a global biodiversity hotspot in eastern Asia. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.D.; Chen, S.C.; Hu, G.W.; Mwachala, G.; Yan, X.; Wang, Q.F. Species richness and phylogenetic diversity of seed plants across vegetation zones of Mount Kenya, East Africa. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 8930–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende, V.L.; Pontara, V.; Bueno, M.L.; van den Berg, E.; de Oliveira-Filho, A.T. Climate and evolutionary history define the phylogenetic diversity of vegetation types in the central region of South America. Oecologia 2020, 192, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus, K.N.G.-E.M.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Correa, H.A.; Hipp, A.L. Phylogenetic niche conservatism drives floristic assembly across Mexico’s Temperate-Tropical divide. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2025, 34, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.B.; Kark, S.; Schneider, C.J.; Wayne, R.K.; Moritz, C. Biodiversity hotspots and beyond: The need for preserving environmental transitions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Pereira, I.; Meira-Neto, J.A.A.; Rezende, V.L.; Eisenlohr, P.V. Biogeographic transitions as a source of high biological diversity: Phylogenetic lessons from a comprehensive ecotone of South America. Perspect. Plant Ecol. 2020, 44, 125528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemessa, D.; Mewded, B.; Alemu, S. Vegetation ecotones are rich in unique and endemic woody species and can be a focus of community-based conservation areas. Bot. Lett. 2023, 170, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, P.; Zhu, H. The tropical-subtropical evergreen forest transition in East Asia: An exploration. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Kuang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Yin, L. Biodiversity conservation in Xishuangbanna, China: Diversity analysis of traditional knowledge related to biodiversity and conservation progress and achievement evaluation. Diversity 2024, 16, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, B.G.; Zhou, S.S.; Zhang, J.H. Studies on the Forest Vegetation of Xishuangbanna. Plant Sci. J. 2015, 33, 641–726. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Cao, M.; Hu, H. Geological history, flora, and vegetation of Xishuangbanna, southern Yunnan, China. Biotropica 2006, 38, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Cao, M. Tropical forest vegetation of Xishuangbanna, SW China and its secondary changes, with special reference to some problems in local nature conservation. Biol. Conserv. 1995, 73, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, B.; Arge, L.; Dalsgaard, B.; Davies, R.G.; Gaston, K.J.; Sutherland, W.J.; Svenning, J.C. The Influence of Late Quaternary Climate-Change Velocity on Species Endemism. Science 2011, 334, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Weigelt, P.; Denelle, P.; Cai, L.; Kreft, H. The contribution of plant life and growth forms to global gradients of vascular plant diversity. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 1548–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, P.; Prieto, M.; Aragon, G.; Escudero, A.; Martinez, I. Critical predictors of functional, phylogenetic and taxonomic diversity are geographically structured in lichen epiphytic communities. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 2303–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Ci, X.Q.; Zhu, R.B.; Conran, J.G.; Li, J. Spatial phylogenetic patterns and conservation of threatened woody species in a transition zone of southwest China. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 2205–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembel, S.W.; Cowan, P.D.; Helmus, M.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Morlon, H.; Ackerly, D.D.; Blomberg, S.P.; Webb, C.O. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.O.; Ackerly, D.D.; Kembel, S.W. Phylocom: Software for the analysis of phylogenetic community structure and trait evolution. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2098–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, C.O. Exploring the Phylogenetic Structure of Ecological Communities_ An Example for Rain Forest Trees. Am. Nat. 2000, 156, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Barker, M.; Rayens, W. Partial least squares for discrimination. J. Chemom. 2003, 17, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohart, F.; Gautier, B.; Singh, A.; Cao, K.A.L. MixOmics: An R package for omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Steven, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2024. R Package Version 2.6-6.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Hu, G.; Pang, Q.; Hu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, C. Beta diversity patterns and determinants among vertical layers of Tropical Seasonal Rainforest in Karst Peak-Cluster Depressions. Forests 2024, 15, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, K. MUMIN: Multi-Modelinference. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Lai, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peres-Neto, P. Generalizing hierarchical and variation partitioning in multiple regression and canonical analyses using the rdacca.hp R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.J.; Donoghue, M.J. The origins of the latitudinal diversity gradient: Revisiting the tropical conservatism hypothesis. J. Biogeogr. 2025, 52, e15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Field, R.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.B. Phylogenetic structure and ecological and evolutionary determinants of species richness for angiosperm trees in forest communities in China. J. Biogeogr. 2016, 43, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelbach, G.G.; Schemske, D.W.; Cornell, H.V.; Allen, A.P.; Brown, J.M.; Bush, M.B.; Harrison, S.P.; Hurlbert, A.H.; Knowlton, N.; Lessios, H.A.; et al. Evolution and the latitudinal diversity gradient: Speciation, extinction and biogeography. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, N.J.B.; Cornwell, W.K.; Webb, C.O.; Ackerly, D.D. Trait Evolution, Community Assembly, and the Phylogenetic Structure of Ecological Communities. Am. Nat. 2007, 170, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, N.J.B.; Adler, P.B.; Godoy, O.; James, E.C.; Fuller, S.; Levine, J.M. Community assembly, coexistence and the environmental filtering metaphor. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 29, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, R.T.; Tomlinson, K.W. Climate Change and Edaphic Specialists: Irresistible Force Meets Immovable Object? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve Management Bureau; Yunnan Institute of Forest Inventory and Planning. Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve; Yunnan Education Publishing House: Kunming, China, 2005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cadotte, M.W.; Davie, J. Phylogenies in Ecology: A Guide to Concepts and Methods; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, L.J.; Thuiller, W.; Jetz, W. Large conservation gains possible for global biodiversity facets. Nature 2017, 546, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda, B.B.; Salinas, F.; Arias, V.M.; Buitrago-Torres, D.L. What is essential is invisible to the eyes: A conservation approach for poison frogs (Dendrobatidae) based on evolutionary distinctiveness and threat status. Biodivers. Conserv. 2025, 34, 1965–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollina, R.J.; Patino, J.; de la Cruz, S.; Olangua-Corral, M.; Marrero, A.; Garcia-Verdugo, C.; Caujape-Castells, J. Integrating a phylogenetic framework for mapping biodiversity patterns to set conservation priorities for an oceanic island flora. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2025, 7, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Chelli, S.; Tsakalos, J.L.; Bricca, A.; Canullo, R.; Cervellini, M.; Pennesi, R.; de Benedictis, L.L.M.; Cesaroni, V.; Bottacci, A.; et al. How effective are different protection strategies in promoting the plant diversity of temperate forests in national parks? For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 584, 122602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, T.H.; Thu, A.M.; Chen, J. Tree species of tropical and temperate lineages in a tropical Asian montane forest show different range dynamics in response to climate change. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morueta-Holme, N.; Enquist, B.; Mcgill, B.J.; Boyle, B.; Jørgensen, P.M.; Ott, J.E.; Peet, R.; Šímová, I.; Sloat, L.L.; Thiers, B.; et al. Habitat area and climate stability determine geographical variation in plant species range sizes. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor, A.F.V.; Schwarzkopf, L.; Krockenberger, A.K. Rapoport’s Rule: Do climatic variability gradients shape range extent? Ecol. Monogr. 2015, 85, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Bagchi, R.; Ellens, J.; Kettle, C.J.; Burslem, D.F.R.P.; Maycock, C.R.; Khoo, E.; Ghazoul, J. Predicting dispersal of auto-gyrating fruit in tropical trees: A case study from the Dipterocarpaceae. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ci, X.; Hu, J.; Bai, Y.; Thornhill, A.H.; Conran, J.G.; Li, J. Riparian areas as a conservation priority under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.P.; Song, Q.H.; Myo, S.T.Z.; Zhou, R.W.; Lin, Y.X.; Liu, Y.T.; Bai, K.C.; Gnanamoorthy, P.; et al. The cumulative drought exert disruptive effects on tropical rainforests in the northern edge of Asia—Based on decadal dendrometric measurements and eddy covariance method. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 316, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.L.; Zaw, Z.; Peng, X.H.; Zhang, H.; Fu, P.L.; Wang, W.L.; Bräuning, A.; Fan, Z.X. Tree rings in Tsuga dumosa reveal increasing drought variability in subtropical southwest China over the past two centuries. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2023, 628, 111757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, S.T.T.; Panthi, S.; Fan, Z.X.; Song, X.Y.; Zhang-Zheng, H.Y.; Zaw, Z.; Lu, H.Z.; Chen, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, R.; et al. Demographic and net primary productivity dynamics of primary and secondary tropical forests in Southwest China under a changing climate. Integr. Conserv. 2024, 3, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.C. The cultural politics of ethnic identity in Xishuangbanna, China: Tea and rubber as “Cash Crops” and “Commodities”. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2012, 41, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Yi, Z.F.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; Ahrends, A.; Beckschäfer, P.; Kleinn, C.; Ranjitkar, S.; Xu, J.C. Pushing the Limits: The Pattern and Dynamics of Rubber Monoculture Expansion in Xishuangbanna, SW China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarathchandra, C.; Dossa, G.G.O.; Ranjitkar, N.B.; Chen, H.F.; Deli, Z.; Ranjitkar, S.; de Silva, K.H.W.L.; Wickramasinghe, S.; Xu, J.C.; Harrison, R.D. Effectiveness of protected areas in preventing rubber expansion and deforestation in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 2417–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damtew, A.; Birhane, E.; Messier, C.; Paquette, A.; Muys, B. Shading and species diversity act as safety nets for seedling survival and vitality of native trees in dryland forests: Implications for restoration. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 552, 121559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemaa, M.; Hotanen, J.; Oksanen, J.; Tonteri, T.; Merila, P. Broadleaved trees enhance biodiversity of the understorey vegetation in boreal forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 546, 121357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Barros, F.V.; Moonlight, P.W.; Hill, T.C.; Oliveira, R.S.; Schmidt, I.B.; Sampaio, A.B.; Pennington, R.T.; Rowland, L. Identifying hotspots for ecosystem restoration across heterogeneous tropical savannah-dominated regions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20210075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; Luo, A.D.; Guo, X.M.; Wang, L.F.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of habitat for Asian elephants (Elephasmaximus) in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2015, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.W.; Liu, P.; Yang, N.; Pan, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L. Spatial-temporal trend and mitigation of human-elephant conflict in Xishuangbanna, China. J. Wildl. Manag. 2023, 87, e22485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, W.; Li, Q.P.; Guo, X.M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.D.; Shen, Q.Z.; Fu, R.F.; Peng, J.Y.; Deng, Z.Y.; et al. Can tropical nature reserves provide and protect cultural ecosystem services? A case study in Xishuangbanna, China. Intergrative Conserv. 2023, 2, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, C.W. Spatio-temporal changes and linear characteristics of rubber plantations in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China from 1987 to 2018. Trop. Trop. Geogr. 2022, 42, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbr. | Variables | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Bio4 | Temperature Seasonality (Standard Deviation × 100) | % |

| Bio6 | Min Temperature of Coldest Month | ℃ |

| Bio13 | Precipitation of Wettest Month | mm |

| Bio14 | Precipitation of Driest Month | mm |

| Bio15 | Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation) | % |

| Bio17 | Precipitation of Driest Quarter | mm |

| Bio18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter | mm |

| MAPano | Annual Precipitation Anomaly since LGM | mm |

| MATano | Annual Mean Temperature Anomaly since LGM | °C |

| Lon | Longitude | ° |

| Lat | Latitude | ° |

| TK | Soil Total Potassium | g/100 g |

| TN | Soil Total Nitrogen | g/100 g |

| AN | Soil Available Nitrogen | mg/kg |

| AP | Soil Available Phosphorus | mg/kg |

| H+ | Soil Exchangeable Hydrogen Ion | me/100 g |

| Mg2+ | Soil Exchangeable Magnesium Ion | me/100 g |

| Al3+ | Soil Exchangeable Aluminum Ion | me/100 g |

| K+ | Soil Exchangeable Potassium Ion | me/100 g |

| PH | PH Soil PH (H2O) | pH units |

| HFI | Human Footprint Index | - |

| ELE | Elevation | m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.-Y.; Ci, X.-Q.; Hu, L.; Zhang, S.-F.; Hu, J.-L.; Li, J. Plant Diversity Patterns and Their Determinants Across a North-Edge Tropical Area in Southwest China. Diversity 2025, 17, 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120833

Zhang X-Y, Ci X-Q, Hu L, Zhang S-F, Hu J-L, Li J. Plant Diversity Patterns and Their Determinants Across a North-Edge Tropical Area in Southwest China. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):833. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120833

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiao-Yan, Xiu-Qin Ci, Ling Hu, Shi-Fang Zhang, Jian-Lin Hu, and Jie Li. 2025. "Plant Diversity Patterns and Their Determinants Across a North-Edge Tropical Area in Southwest China" Diversity 17, no. 12: 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120833

APA StyleZhang, X.-Y., Ci, X.-Q., Hu, L., Zhang, S.-F., Hu, J.-L., & Li, J. (2025). Plant Diversity Patterns and Their Determinants Across a North-Edge Tropical Area in Southwest China. Diversity, 17(12), 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120833