Habitat Fragmentation on Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Diversity, Food Niches, and Bee–Plant Interaction Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Evaluate the effects of habitat fragmentation on bee abundance, richness, and α- and β-diversity in a protected and a fragmented area.

- (2)

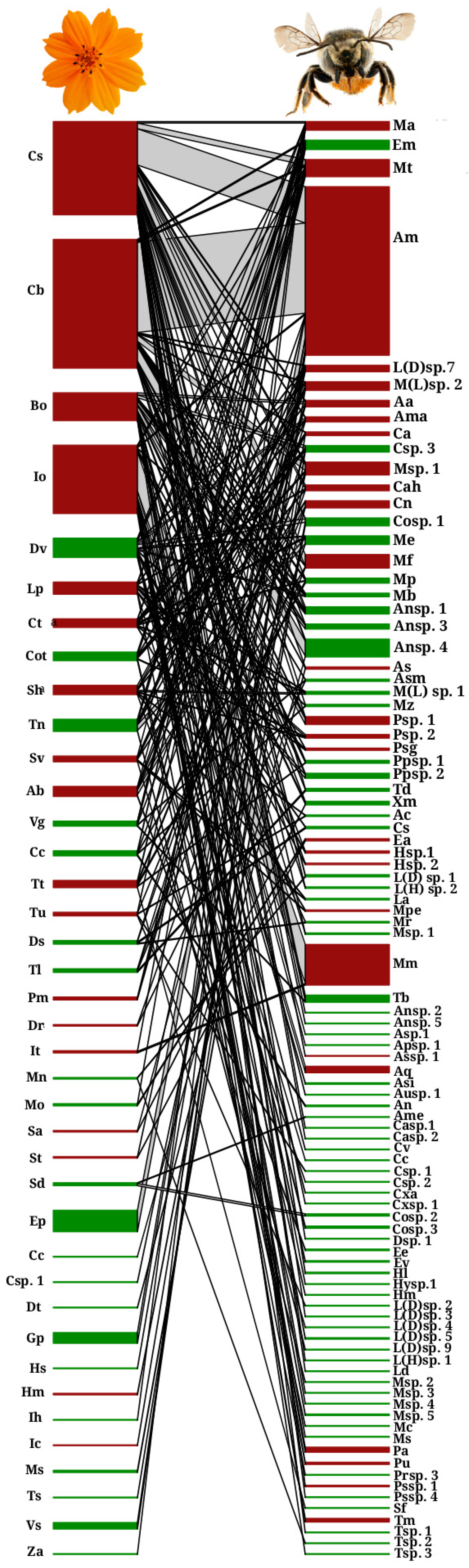

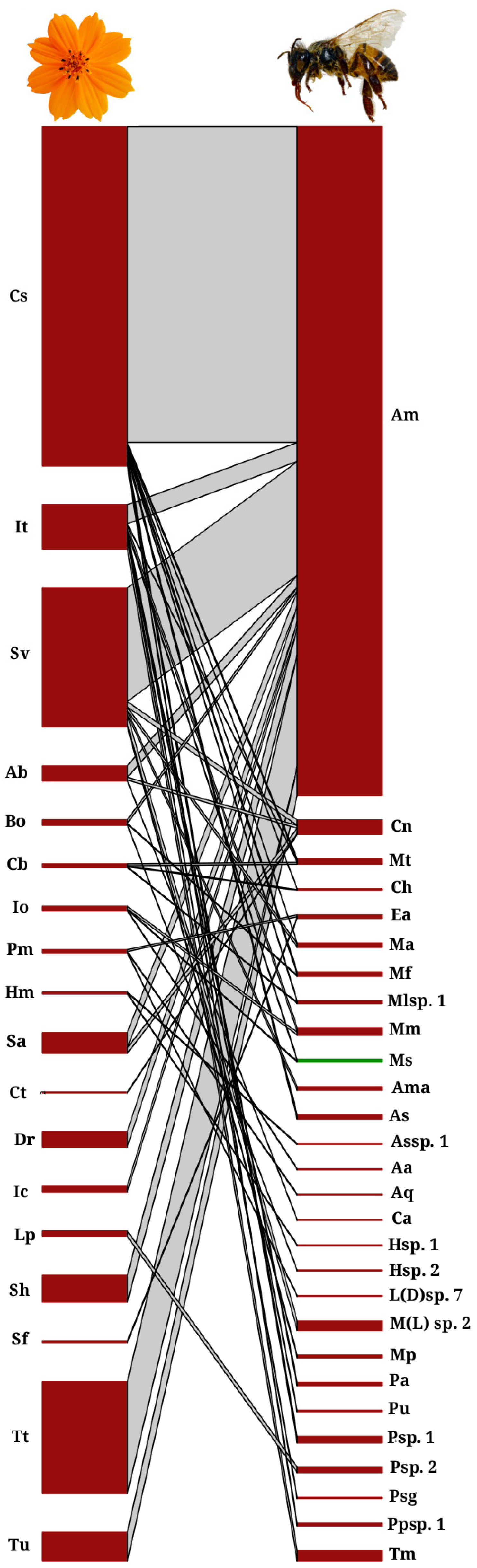

- Compare the structure of plant–bee interactions between both conditions.

- (3)

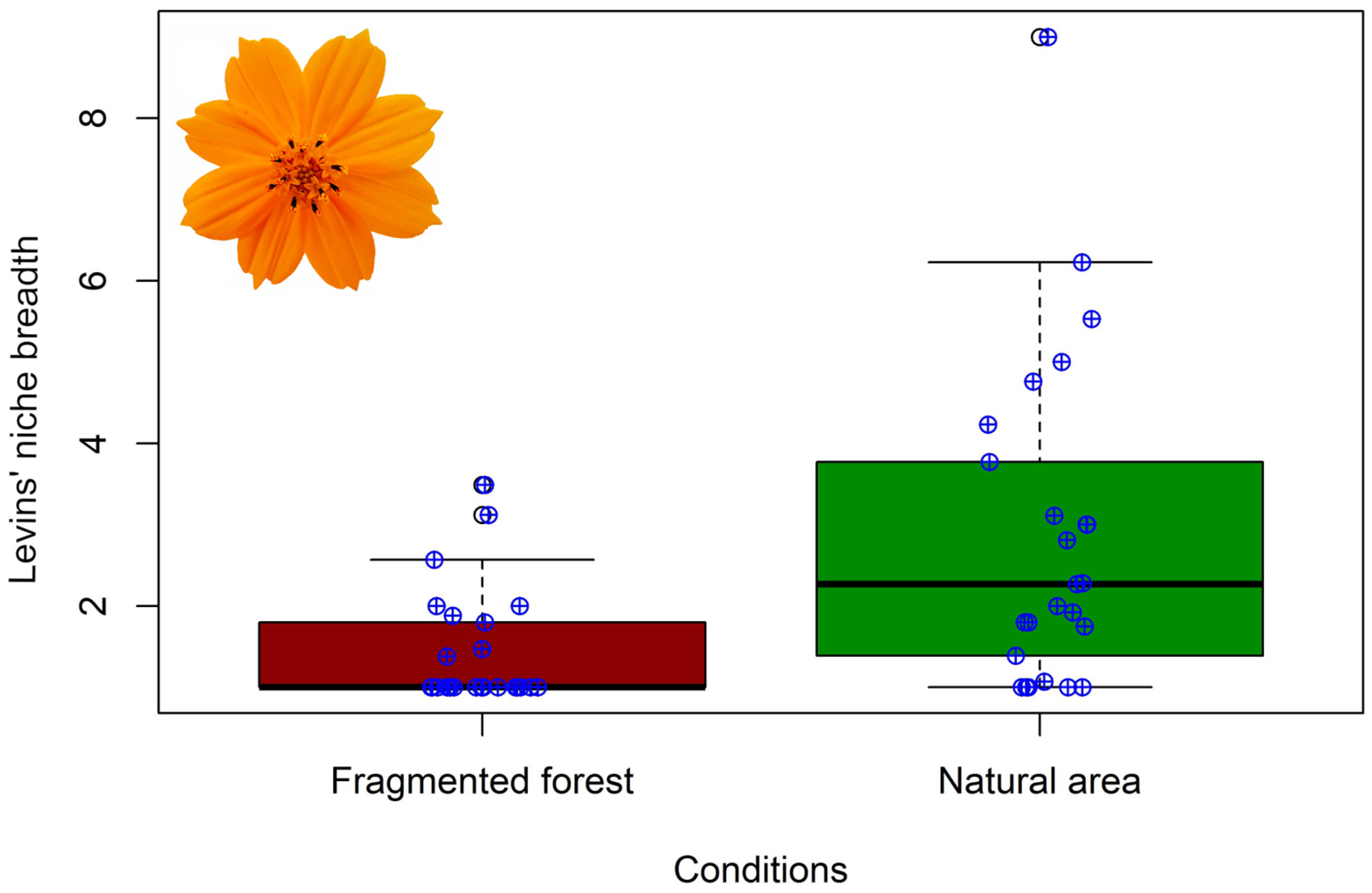

- Determine bee species responses to fragmentation based on their feeding niche breadth and overlap.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Abundance

3.2. Diversity α y β

4. Discussion

4.1. Bee Community Structure

4.2. Network Metrics

4.3. Niche Breadth and Overlap

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NA | Natural area |

| FF | Fragmented forest |

| q0 | Richness |

| q1 | Common species |

| q2 | Dominant species |

| βSor | Sorensen’s dissimilarity index |

| βSim | Species turnover index |

| βSne | Nesting components index |

| H2′ | Shannon–Weiner index for interactions |

| βWN | Diversity of interactions index |

| βST | Diversity of interactions due to species turnover |

| βOS | Diversity of interactions established between species common to both communities |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Family | Species | Acronyms | FF | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colletidae | Colletes sp. 1 | Cosp.1 | 0 | 11 |

| Colletes sp. 2 | Cosp.2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Colletes sp. 3 | Cosp.3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Hylaeus sp. 1 | Hsp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Andrenidae | Andrena sp. 1 | Ansp. 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Andrena sp. 2 | Ansp. 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Andrena sp. 3 | Ansp. 3 | 0 | 7 | |

| Andrena sp. 4 | Ansp. 4 | 0 | 25 | |

| Andrena sp. 5 | Ansp. 5 | 0 | 1 | |

| Calliopsis sp. 1 | Casp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Calliopsis sp. 2 | Casp. 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Calliopsis hondurasica | Cah | 2 | 8 | |

| Protandrena sp. 1 | Psp. 1 | 7 | 11 | |

| Protandrena sp. 2 | Psp. 2 | 6 | 5 | |

| Protandrena sp. 3 | Psp. 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pseudopanurgus sp. 1 | Ppsp. 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Pseudopanurgus sp. 2 | Ppsp. 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Pseudopanurgus sp. 3 | Ppsp. 3 | 0 | 7 | |

| Pseudopanurgus sp. 4 | Ppsp. 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Halictidae | Augochlora aurifera | Aa | 1 | 9 |

| Augochlora quiringuensis | Aq | 1 | 9 | |

| Augochlora sidaefolia | Asi | 0 | 2 | |

| Augochlora smaragdina | Asm | 0 | 3 | |

| Augochlora sp. 1 | Ausp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Augochlorella neglectula | An | 0 | 2 | |

| Augochloropsis metallica | Ame | 0 | 1 | |

| Halictus ligatus | Hl | 0 | 2 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 1 | L(D) sp. 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 2 | L(D) sp. 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 3 | L(D) sp. 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 4 | L(D) sp. 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 5 | L(D) sp. 5 | 0 | 2 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 7 | L(D) sp. 7 | 1 | 9 | |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 9 | L(D) sp. 9 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lasioglossum (H.) sp. 1 | L(H) sp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lasioglossum (H.) sp. 2 | L(H) sp. 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Lasioglossum acarophylum | La | 0 | 2 | |

| Lasioglossum desertum | Ld | 0 | 1 | |

| Pseudoaugochlora gramminea | Psg | 2 | 3 | |

| Megachilidae | Anthidium maculifrons | Ama | 4 | 7 |

| Ashmeadiella sp. 1 | Assp. 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Coelyoxys azteca | Cxa | 0 | 1 | |

| Coelyoxys sp. 1 | Cxsp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Dianthidium sp. 1 | Dsp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Heriades sp. 1 | Hsp. 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Heriades sp. 2 | Hsp. 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Hypanthidium mexicanum | Hm | 0 | 1 | |

| Megachile (Leptorachis) sp. 1 | M(L)sp. 1 | 0 | 4 | |

| Megachile (Leptorachis) sp. 2 | M(L)sp. 2 | 11 | 12 | |

| Megachile albitarsis | Ma | 5 | 12 | |

| Megachile exilis | Me | 0 | 12 | |

| Megachile flavihirsuta | Mf | 5 | 19 | |

| Megachile paralella | Mp | 0 | 7 | |

| Megachile petulans | Mpe | 3 | 2 | |

| Megachile reflexa | Mr | 0 | 2 | |

| Megachile sp. 1 | Msp. 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Megachile sp. 2 | Msp. 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Megachile sp. 3 | Msp. 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Megachile sp. 4 | Msp. 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Megachile sp. 5 | Msp. 5 | 0 | 2 | |

| Megachile zapoteca | Mz | 0 | 3 | |

| Apidae | Anthophora capistrata | Ac | 0 | 2 |

| Anthophora sp. 1 | Asp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Anthophora squammulosa | As | 5 | 3 | |

| Antophorula sp. 1 | Apsp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Apis mellifera | Am | 741 | 237 | |

| Centris atripes | Ca | 1 | 5 | |

| Centris nitida | Cn | 16 | 10 | |

| Centris varia | Cv | 0 | 1 | |

| Cetris sericea | Cs | 0 | 3 | |

| Ceratina capitosa | Cc | 0 | 1 | |

| Ceratina sp. 1 | Csp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ceratina sp. 2 | Csp. 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ceratina sp. 3 | Csp. 3 | 0 | 9 | |

| Epicharis elegans | Ee | 0 | 2 | |

| Euglossa viridissima | Ev | 0 | 2 | |

| Exomalopsis arida | Ea | 4 | 3 | |

| Exomalopsis moesta | Em | 0 | 13 | |

| Melissodes communis | Mc | 0 | 1 | |

| Melissodes sp. 1 | Msp. 1 | 3 | 18 | |

| Melissodes tepaneca | Mt | 6 | 24 | |

| Melitoma marginella | Mm | 8 | 57 | |

| Melitoma segmentaria | Ms | 3 | 1 | |

| Mesocheira bicolor | Mb | 0 | 5 | |

| Peponapis azteca | Pa | 4 | 7 | |

| Peponapis utahensis | Pu | 2 | 3 | |

| Syntricalonia fuliginea | Sf | 0 | 1 | |

| Tetraloniella balluca | Tb | 0 | 10 | |

| Tetraloniella donata | Td | 0 | 4 | |

| Thygater montezuma | Tm | 12 | 5 | |

| Triepeolus sp. 1 | Tsp. 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Triepeolus sp. 2 | Tsp. 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Triepeolus sp. 3 | Tsp. 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Xylocopa mexicanorum | Xm | 0 | 5 |

Appendix A.2

| Family | Species | Acronyms |

|---|---|---|

| Asparagaceae | Prochnyanthes mexicana | Pm |

| Asteraceae | Bidens odorata | Bo |

| Conyza canadensis | Cc | |

| Cosmos bipinnatus | Cb | |

| Cosmos sulphureus | Cs | |

| Dysodia tagetiflora | Dt | |

| Galinsoga parviflora | Gp | |

| Iostephane heterophylla | Ih | |

| Lasianthaea palmeri | Lp | |

| Tagetes lucida | Tl | |

| Tithonia tubaeformis | Tt | |

| Verbesina greenmanii | Vg | |

| Verbesina sphaerocephala | Vs | |

| Zinnia angustifolia | Za | |

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma stans | Ts |

| Comelinaceae | Comelina tuberosa | Ctu |

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea capillaceae | Ic |

| Ipomea orizabaensis | Io | |

| Ipomoea tyrianthina | It | |

| Cruciferaceae | Cruciferaceae sp.1 | Crusp. 1 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Sycios deppei | Sd |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton ciliatoglandulifer | Cc |

| Fabaceae | Clitoria trifollia | Ct |

| Dalea roseiflora | Dr | |

| Dalea versicolor | Dv | |

| Desmodium sericophyllum | Ds | |

| Eysenhardtia polystachya | Ep | |

| Marina neglecta | Mn | |

| Marina scopa | Ms | |

| Mimosa occidentalis | Mo | |

| Solanum ferrogineum | Sf | |

| Tephrosia nicaraguensis | Tn | |

| Hydroleaceae | Hydrolea spinosa | Hs |

| Lamiaceae | Hyptis mutabilis | Hm |

| Salvia angustiarum | Sa | |

| Salvia heterotricha | Sh | |

| Salvia veronicaefolia | Sv | |

| Malpigiaceae | Aspicarpa brevipes | Ab |

| Solanaceae | Solanum ferrogineum | Sf |

| Turneraceae | Turnera ulmifolia | Tu |

References

- Felker, P.; Bunch, R. The importance of native bees, especially cactus bees (Diadasia spp.), in the pollination of cactus pears. J. Prof. Assoc. Cactus Dev. 2016, 18, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; James, R.R.; Pitts-Singer, T.L. Crop pollination services from wild bees. In Bee Pollination in Agricultural Ecosystems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, C.S.S.; Maués, M.M. Insect Pollinators, Major Threats and Mitigation Measures. Neotrop. Entomol. 2020, 49, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.; Laskar, N. Nature’s Matchmakers: Insects and their Pollination Services for Crops. J. Agric. Ecol. Res. Int. 2025, 26, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, B.V.M.R.; Viguera, M.R. Impactos Del Cambio Climático en la Agricultura de Centroamérica, Estrategias de Mitigación y Adaptación; Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE): Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zattara, E.E.; Aizen, M.A. Worldwide occurrence records suggest a global decline in bee species richness. One Earth 2021, 4, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.J.; Paxton, R.J. The conservation of bees: A global perspective. Apidologie 2009, 40, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, J.; Fragoso, F.P. What are the main reasons for the worldwide decline in pollinator populations? CABI Rev. 2024, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, O.; Joshi, N.K. Mitigating the effects of habitat loss on solitary bees in agricultural ecosystems. Agriculture 2020, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D.; Nicholls, E.; Botías, C.; Rotheray, E.L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 2015, 347, 1255957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, C.; Martínez, E.; Arriaga, L. Deforestación y fragmentación de ecosistemas: Qué tan grave es el problema en México. Biodiversitas 2000, 30, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Townshend, J.R.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Calvillo, L.; Meléndez Ramírez, V.; Parra-Tabla, V.; Navarro, J. Bee diversity in a fragmented landscape of the Mexican neotropic. J. Insect Conserv. 2010, 14, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfree, R.; Bartomeus, I.; Cariveau, D.P. Native pollinators in anthropogenic habitats. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2011, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortel, L.; Henry, M.; Guilbaud, L.; Mouret, H.; Vaissière, B.E. Use of human-made nesting structures by wild bees in an urban environment. J. Insect Conserv. 2016, 20, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, T.; Malik, M.F.; Naseem, S.; Azzam, A. Habitat fragmentation-a menace of biodiversity: A review. Int. J. Fauna Biol. Stud. 2018, 5, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ojija, F. Biodiversity and plant-insect interactions in fragmented habitats: A systematic review. CAB Rev. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulting, K.A.; Brudvig, L.A.; Damschen, E.I.; Levey, D.J.; Resasco, J.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Haddad, N.M. Habitat edges decrease plant reproductive output in fragmented landscapes. J. Ecol. 2024, 113, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauker, F.; Jauker, B.; Grass, I.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Wolters, V. Partitioning wild bee and hoverfly contributions to plant–pollinator network structure in fragmented habitats. Ecology 2019, 100, e02569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.A.; Boscolo, D.; Lopes, L.E.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; da Rocha, P.L.B.; Viana, B.F. Forest and connectivity loss simplify tropical pollination networks. Oecologia 2020, 192, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librán-Embid, F.; Grass, I.; Emer, C.; Ganuza, C.; Tscharntke, T. A plant–pollinator metanetwork along a habitat fragmentation gradient. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 2700–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Dong, M. The diverse effects of habitat fragmentation on plant–pollinator interactions. Plant Ecol. 2016, 217, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierros-López, H.E. Cetoninos de dos localidades de Jalisco, México (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Cetoniinae). Dugesiana 2008, 15, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, A.G.H.; Rivera, L.S.H. Comité Salvabosque, en defensa del bosque El Nixticuil. In Informe Sobre la Situación de Los Derechos Humanos en Jalisco; Centro de Justicia Para la Paz y el Desarrollo AC: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2009; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- IIEG. Instituto de Información Estadística y Geográfica Del Estado de Jalisco Con Base en INEGI, Censos y Conteos Nacionales. 2020. Available online: https://iieg.gob.mx/ns/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/AMG.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Michener, C.D.; McGinley, R.J.; Danforth, B.N. The Bee Genera of North and Central America (Hymenoptera: Apoidea); Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. viii+-209. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Chao, A.; Jost, L. Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: Standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology 2012, 93, 2533–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.; Chao, A. iNEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-7. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Dormann, C.F.; Gruber, B.; Fründ, J. Introducing the bipartite package: Analysing ecological networks. R News 2008, 8, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jordano, P. Patterns of mutualistic interactions in pollination and seed dispersal: Connectance, dependence asymmetries, and coevolution. Am. Nat. 1987, 129, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüthgen, N.; Menzel, F.; Blüthgen, N. Measuring specialization in species interaction networks. BMC Ecol. 2006, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordano, P.; Vázquez, D.; Bascompte, J. Redes complejas de interacciones mutualistas planta-animal. In Ecología y Evolución de Interacciones Planta Animal: Conceptos y Aplicaciones; Medel, R., Aizen, M., Zamora, R., Eds.; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2009; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Atmar, W.; Patterson, B.D. The measure of order and disorder in the distribution of species in fragmented habitat. Oecologia 1993, 96, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascompte, J.; Jordano, P. Redes mutualistas de especies. Investig. Cienc. 2008, 384, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bascompte, J.; Jordano, P. The structure of plant–animal mutualistic networks. In Ecological Networks; Pascual, M., Dunne, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.F.; Fründ, J.; Blüthgen, N.; Gruber, B. Indices, graphs and null models: Analyzing bipartite ecological networks. Open Ecol. J. 2009, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, V. Beta diversity of plant-insect food webs in tropical forests: A conceptual framework. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2009, 2, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisot, T.; Canard, E.; Mouillot, D.; Mouquet, N.; Gravel, D.; Jordan, F. The dissimilarity of species interaction networks. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, G.; Bastazini, V.A.; Debastiani, V.J.; Pillar, V.D. Assessing sampling sufficiency of network metrics using bootstrap. Ecol. Complex. 2018, 36, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc.: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylianakis, J.M.; Didham, R.K.; Bascompte, J.; Wardle, D.A. Global change and species interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Martínez, C.; Aase, A.L.T.; Totland, Ø.; Rodríguez-Pérez, J.; Birkemoe, T.; Sverdrup-Thygeson, A.; Lázaro, A. Forest fragmentation modifies the composition of bumblebee communities and modulates their trophic and competitive interactions for pollination. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosi, B.J. The effects of forest fragmentation on euglossine bee communities (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Euglossini). Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plascencia, M.; Philpott, S.M. Floral abundance, richness, and spatial distribution drive urban garden bee communities. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2017, 107, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.H. Habitat fragmentation and native bees: A premature verdict? Conserv. Ecol. 2001, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.H.; Minckley, R.L.; Kervin, L.J.; Roulston, T.A.H.; Williams, N.M. Complex responses within a desert bee guild (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) to urban habitat fragmentation. Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrié, R.; Andrieu, E.; Cunningham, S.A.; Lentini, P.E.; Loreau, M.; Ouin, A. Relationships among ecological traits of wild bee communities along gradients of habitat amount and fragmentation. Ecography 2017, 40, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, C.D. The Bees of the World; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roubik, D.W. Ecology and Natural History of Tropical Bees; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Winfree, R.; Aguilar, R.; Vázquez, D.P.; LeBuhn, G.; Aizen, M.A. A meta-analysis of bees’ responses to anthropogenic disturbance. Ecology 2009, 90, 2068–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, L.K.; Mola, J.M.; Portman, Z.M.; Cariveau, D.P.; Smith, H.G.; Bartomeus, I. The potential and realized foraging movements of bees are differentially determined by body size and sociality. Ecology 2002, 103, e3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizen, M.A.; Feinsinger, P. Bees not to be? Responses of insect pollinator faunas and flower pollination to habitat fragmentation. In How Landscapes Change: Human Disturbance and Ecosystem Fragmentation in the Americas; Bradshaw, G.A., Marquet, P.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.P.; De Santis, A.A.; Armas-Quiñonez, G.; Ascher, J.S.; Ávila-Gómez, E.S.; Báldi, A.; Ballare, K.M.; Balzan, M.V.; Banaszak-Cibicka, W.; Bonebrake, T.C.; et al. Land use change consistently reduces α- but not β- and γ-diversity of bees. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Urias, A.; Araujo-Alanis, L.; Huerta-Martínez, F.M.; Jacobo-Pereira, C.; Razo-León, A.E. Effects of urbanization and floral diversity on the bee community (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) in an oak forest in a protected natural area of Mexico. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2025, 98, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizen, M.A.; Feinsinger, P. Habitat fragmentation, native insect pollinators, and feral honey bees in Argentine Chaco Serrano. Ecol. Appl. 1994, 4, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, A.S.; Betts, M.G. The effects of landscape fragmentation on pollination dynamics: Absence of evidence not evidence of absence. Biol. Rev. 2012, 87, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, C.M.; Lonsdorf, E.; Neel, M.C.; Williams, N.M.; Ricketts, T.H.; Winfree, R.; Brittain, C.; Burley, A.L.; Cariveau, D.; Kremen, C.; et al. A global quantitative synthesis of local and landscape effects on wild bee pollinators in agroecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, M.; Rosas, F.; López, M.; Araiza, M.; Aguilar, R.; Ashworth, L.; Rosas, G.V.; Sánchez, M.G.; Martén, R.S. Ecología y conservación biológica de sistemas de polinización de plantas tropicales. In Ecología y Evolución de Las Interacciones Bióticas; del Val, E., Bouge, K., Eds.; Fondo de Cultura Económica, CIECO y UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- Tylianakis, J.M.; Laliberté, E.; Nielsen, A.; Bascompte, J. Conservation of species interaction networks. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2270–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenla, J.L.; García, Y.F.; de Zayas, Á.Á.; Nápoles, N.R. Red de interacciones bipartitas de visitantes florales en Guanabo, Playas del Este, La Habana, Cuba. Poeyana 2023, 514, e514. [Google Scholar]

- Aizen, M.A.; Sabatino, M.; Tylianakis, J.M. Specialization and rarity predict nonrandom loss of interactions from mutualist networks. Science 2012, 335, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emer, C.; Galetti, M.; Pizo, M.A.; Guimaraes, P.R., Jr.; Moraes, S.; Piratelli, A.; Jordano, P. Seed-dispersal interactions in fragmented landscapes—A metanetwork approach. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, M.A.; Bascompte, J. Habitat loss and the structure of plant–animal mutualistic networks. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdovinos, F.S.; Brosi, B.J.; Briggs, H.M.; Moisset de Espanes, P.; Ramos-Jiliberto, R.; Martinez, N.D. Niche partitioning due to adaptive foraging reverses effects of nestedness and connectance on pollination network stability. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M.; Kissling, W.D.; Rasmussen, C.; De Aguiar, M.A.; Brown, L.E.; Carstensen, D.W.; Yoko, L.D.; Francois, K.E.; Genini, J.; Olesen, J.M.; et al. Biodiversity, species interactions and ecological networks in a fragmented world. Adv. Ecol. Res. 2012, 46, 89–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, D.P.; Morris, W.F.; Jordano, P. Interaction frequency as a surrogate for the total effect of animal mutualists on plants. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascompte, J.; Jordano, P. Mutualistic Networks; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser-Bunbury, C.N.; Mougal, J.; Whittington, A.E.; Valentin, T.; Gabriel, R.; Olesen, J.M.; Blüthgen, N. Ecosystem restoration strengthens pollination network resilience and function. Nature 2017, 542, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüthgen, N.; Menzel, F.; Hovestadt, T.; Fiala, B.; Blüthgen, N. Specialization, constraints, and conflicting interests in mutualistic networks. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fründ, J.; Dormann, C.F.; Holzschuh, A.; Tscharntke, T. Bee diversity effects on pollination depend on functional complementarity and niche shifts. Ecology 2013, 94, 2042–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkle, L.A.; Alarcón, R. The future of plant–pollinator diversity: Understanding interaction networks across time, space, and global change. Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bee Family | NA | FF | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apidae | 439 | 806 | 1 | 215.19 | <0.05 |

| Apidae * | 202 | 75 | 1 | 114.63 | <0.05 |

| Megachilidae | 97 | 31 | 1 | 66.01 | <0.05 |

| Halictidae | 56 | 4 | 1 | 86.7 | <0.05 |

| Andrenidae | 85 | 18 | 1 | 84.58 | <0.05 |

| Colletidae | 18 | 0 | 1 | 32.1 | <0.05 |

| NA | FF | |

|---|---|---|

| Observed bee richness | 94 | 28 |

| Observed plant richness | 39 | 18 |

| Observed connectance | 6.02 | 9.92 |

| Estimated connectance | 5.9 (5.3–6.4) | 10 (9.1–11.6) |

| Observed web asymmetry | 0.41 | 0.21 |

| Estimated web asymmetry | 0.38 (0.33–0.42) | 0.16 (0.10–0.22) |

| Observed nestedness | 3.79 | 10.08 |

| Estimated nestedness | 4.47 (3.68–5.66) | 8.78 (7.02–10.69) |

| Observed interaction Shannon diversity | 4.22 (68) | 2.27 (10) |

| Estimated interaction Shannon diversity | 4.04 (3.9–4.19) | 2.24 (2.13–2.38) |

| Observed interaction evenness | 0.51 | 0.36 |

| Estimated interaction evenness | 0.51 (0.49–0.52) | 0.37 (0.35–0.39) |

| Observed interaction strength asymmetry | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Estimated interaction strength asymmetry | 0.17 (0.13–0.21) | 0.07 (−0.04–0.17) |

| Observed specialization asymmetry | −0.05 | 0.36 |

| Estimated specialization asymmetry | −0.06 (−0.09–−0.03) | 0.36 (0.24–0.45) |

| Observed H2′ | 0.57 | 0.49 |

| Estimated H2′ | 0.63 (0.61–0.66) | 0.49(0.42–0.56) |

| Observed bee niche overlap | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Estimated bee niche overlap | 0.12 (0.09–0.13) | 0.15 (0.12–0.19) |

| Observed plant niche overlap | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| Estimated plant niche overlap | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) | 0.36 (0.30–0.45) |

| Species | B NA | B FF | Morisita–Horn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thygater montezuma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Peponapis azteca * | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pseudoaugochlora gramminea | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Augochlora aurifera | 4.76 | 1 | 0 |

| Augochlora quiringuensis | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Protandrena sp. 1 | 1.75 | 1 | 0.1157 |

| Lasioglossum (D.) sp. 7 | 6.23 | 1 | 0.1914 |

| Anthidium maculifrons | 3.77 | 1 | 0.2258 |

| Megachile albitarsis | 9 | 1.47 | 0.2528 |

| Megachile (L.) sp. 2 | 4.23 | 1 | 0.2696 |

| Exomalopsis arida | 1.8 | 2 | 0.3157 |

| Apis mellifera | 2.81 | 3.49 | 0.3174 |

| Centris atripes | 5 | 1 | 0.3333 |

| Heriades sp. 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.4285 |

| Centris nitida | 1.92 | 3.12 | 0.4908 |

| Anthophora squammulosa | 3 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Melitoma marginella * | 1.07 | 2.8 | 0.5244 |

| Melissodes sp. 1 | 3.11 | 1.8 | 0.6338 |

| Megachile petulans | 2 | 1 | 0.6666 |

| Calliopsis hondurasica | 2.28 | 2 | 0.6666 |

| Heriades sp. 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.67 |

| Melissodes tepaneca | 5.53 | 2.57 | 0.6829 |

| Protandrena sp. 2 | 2.27 | 1 | 0.8333 |

| Megachile flavihirsuta | 1.39 | 1.38 | 0.9748 |

| Ashmeadiella sp. 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pseudopanurgus sp. 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Peponapis utahensis * | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Razo-León, A.E.; Huerta-Martínez, F.M.; Becerra-Chiron, I.M.; Jacobo-Pereira, C.; Neri-Luna, C.; Araujo-Alanis, L.; Muñoz-Urias, A. Habitat Fragmentation on Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Diversity, Food Niches, and Bee–Plant Interaction Networks. Diversity 2025, 17, 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120834

Razo-León AE, Huerta-Martínez FM, Becerra-Chiron IM, Jacobo-Pereira C, Neri-Luna C, Araujo-Alanis L, Muñoz-Urias A. Habitat Fragmentation on Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Diversity, Food Niches, and Bee–Plant Interaction Networks. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):834. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120834

Chicago/Turabian StyleRazo-León, Alvaro Edwin, Francisco Martín Huerta-Martínez, Iskra Mariana Becerra-Chiron, Cesar Jacobo-Pereira, Cecilia Neri-Luna, Lisset Araujo-Alanis, and Alejandro Muñoz-Urias. 2025. "Habitat Fragmentation on Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Diversity, Food Niches, and Bee–Plant Interaction Networks" Diversity 17, no. 12: 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120834

APA StyleRazo-León, A. E., Huerta-Martínez, F. M., Becerra-Chiron, I. M., Jacobo-Pereira, C., Neri-Luna, C., Araujo-Alanis, L., & Muñoz-Urias, A. (2025). Habitat Fragmentation on Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Diversity, Food Niches, and Bee–Plant Interaction Networks. Diversity, 17(12), 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120834