Abstract

This study documents the diversity, ethnobotany, and ethnolinguistic aspects of Passifloraceae species in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, Thailand. Field surveys conducted from April 2024 to March 2025 recorded nine taxa across three genera, including two native species (Adenia heterophylla and A. viridiflora) newly reported for Buri Ram Province, and seven taxa (Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. miniata, P. trifasciata, P. vesicaria, Turnera subulata, and T. ulmifolia) representing new provincial records. Native species were primarily associated with dry dipterocarp and mixed deciduous forests, whereas introduced taxa occurred mainly in cultivated or disturbed habitats, reflecting both ecological adaptability and human-mediated introduction. Ethnobotanical data revealed diverse uses including food, traditional medicine, ornamentals, beverages, and economic purposes with P. edulis f. flavicarpa and A. viridiflora having particularly high cultural and economic significance. Passiflora flower also holds cultural prominence, inspiring local and iconic textile motifs of Non Din Daeng. Vernacular names and terminology provide insights into local classification systems and cultural perceptions of these plants. Conservation assessments indicate potential threats to A. heterophylla from wild harvesting, whereas cultivated and naturalized Passiflora taxa are assessed as Least Concern. The results highlight the ecological, cultural, and economic value of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District and emphasize the role of community knowledge in biodiversity conservation and sustainable management.

Keywords:

Adenia; diversity; economic values; ethnobotany; Non Din Daeng; Passiflora; Thailand; Turnera 1. Introduction

The family Passifloraceae, a member of the order Malpighiales [1], encompasses a wide range of morphologically diverse climbing plants, shrubs, and small trees that occur primarily in tropical and subtropical regions [2,3,4]. Globally, Passifloraceae includes 31 accepted genera and approximately 1046 species [2]. The most well-known genus, Passiflora L., is widely appreciated for its complex floral morphology, vibrant appearance, and extensive horticultural use, as well as its importance in global fruit markets [5,6,7,8]. Other genera, such as Adenia Forssk., are equally diverse, particularly in African and Asian regions [2], where both Passiflora and Adenia are known for their medicinal value and toxic properties [9,10,11,12,13]. Despite this broad significance, regional studies remain limited, especially in Southeast Asia, where taxonomic confusion, sparse herbarium representation, and underexplored ethnobotanical knowledge have impeded comprehensive understanding [3,14,15,16].

In Thailand, Passifloraceae is represented by five genera: Adenia, Passiflora, Paropsia Noronha ex Thouars, Piriqueta Aubl., and Turnera L. [3,4]. Six species of Adenia and five species of Passiflora are recognized, with Paropsia represented by a single tree species native to Peninsular Thailand. Among these, P. edulis Sims, P. laurifolia L., and P. quadrangularis L. are widely cultivated for their sweet, aromatic fruits, contributing to local consumption and the regional horticultural trade. Passiflora edulis, in particular, holds economic significance, being frequently sold in markets and used in the preparation of beverages, desserts, and preserves [3]. Meanwhile, species such as P. foetida L. are naturalized and commonly found in disturbed habitats [4], while others P. caerulea L. and P. suberosa L. are reported in the literature but remain unverified by herbarium records in Thailand, highlighting the ongoing challenge of confirming the presence of cultivated or escaped species, especially in ecotonal or rural landscapes [3]. In a subsequent contribution to Flora of Thailand, Volume 14, Part 3 recorded three additional taxa in the family, including Piriqueta racemosa (Jacq.) Sweet, noted as naturalized in Thailand without locality data, and two cultivated species of T. subulata Sm. and T. ulmifolia L. [4].

Many areas in Thailand, especially in the eastern region, remain poorly surveyed, particularly concerning Passifloraceae, which has not been officially recorded in Buri Ram Province despite field observations indicating its presence [3,4]. This reflects a lack of up-to-date regional data and limited attention to traditional plant use in local communities. Most taxonomic, ethnobotanical, or ethnomedicinal studies have focused on other plant families [17,18,19]. A previous study investigated the medicinal plant knowledge of certified folk healers in Buri Ram Province, but no species from the Passifloraceae family were included [20]. While the study highlights the presence of traditional healing practices in the region, no species from Passifloraceae were recorded. This points to a gap in current ethnobotanical records and underscores the need for further research. Ethnobotanical studies emphasize the importance of integrating local knowledge with botanical exploration, especially in regions where plant use is passed down orally and embedded in daily life. Amid ongoing land-use changes and cultural shifts, documenting plant use alongside species distribution is essential.

Moreover, the discovery of Passifloraceae usage at the community level could serve as a foundation for further studies in various fields, such as the development of herbal medicines, the creation of community-based products, and the promotion of sustainable plant utilization. These efforts can support both local livelihoods and the conservation of biodiversity. Notably, international studies have identified several species within Passifloraceae that contain bioactive compounds with significant medicinal and therapeutic potential [21,22,23,24,25,26].

The objective of this research is to record the diversity of species, horticultural roles, economic value, and traditional uses of Passifloraceae in the Non Din Daeng District of Buri Ram Province. Through a combination of botanical field surveys and ethnobotanical interviews, this work provides the first record of this plant family in the area. The findings contribute to a better understanding of regional plant biodiversity, encourage conservation of valuable native and introduced species, and may inform future studies on the phytochemical and medicinal properties of locally used taxa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

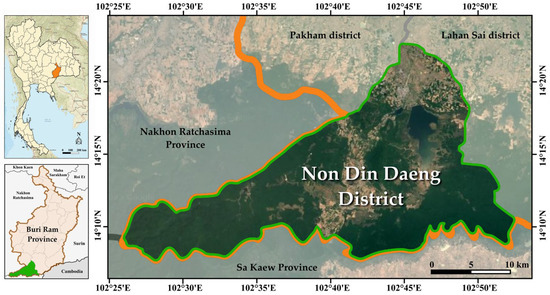

Non Din Daeng District (Figure 1), located at approximately 14°18′57″ N, 102°44′37″ E, in the southern part of Buri Ram Province in eastern Thailand, is bordered by Lahan Sai and Pakham districts to the north, Soeng Sang District of Nakhon Ratchasima Province to the west, and Sa Kaeo Province to the south. The district spans an area of 448.0 km2, with an elevation ranging from 205 m in the northern lowlands to 675 m at the peaks of the Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary mountains. The climate belongs to the tropical savanna (Aw) zone according to the Köppen–Geiger classification [27], general temperatures ranged from 19 °C to 35 °C, with January 2025 being the coolest month (13 °C) and late April 2024 the hottest (44 °C), rarely falling below 15 °C or exceeding 38 °C, and mean annual temperatures of 27–28 °C. Annual rainfall from April 2024 to March 2025 was about 164 mm, concentrated during the rainy season [28]. Land cover includes forested areas, agricultural land, and the southern portion is dominated by the mountainous Sankamphaeng Range. Administratively, Non Din Daeng is divided into three subdistricts and 45 villages. This diverse environment, with its varied topography and ecosystems, provides an ideal setting for ecological and biodiversity studies.

Figure 1.

Geographic location and boundaries of Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, Thailand. The left panels depict the position of Buri Ram Province (orange part) within Thailand (top) and the location of Non Din Daeng District (green part) within Buri Ram Province (bottom left). The main panel (right) presents a detailed map of Non Din Daeng District with its boundary outlined in green, while the orange line is the boundary of Buri Ram Province, which adjacent to Nakhon Ratchasima Province in the west and Sa Kaew Province in the south.

All graphical content for this article was prepared by Thawatphong Boonma with Pixelmator Pro (Version 3.6.15, Archipelago, 2025; Pixelmator Team, Vilnius, Lithuania).

2.2. Data Collection

Field expeditions were carried out from April 2024 to March 2025, with two to four visits per month, to survey Passifloraceae species in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, Eastern Thailand. Species were documented across a variety of habitat types. In protected areas, to minimize environmental disturbance, no physical specimens were collected; instead, observations were recorded using photographs and detailed field notes [29].

2.3. Taxonomic Identification

Specimens were identified based on their morphological features, which were carefully examined under a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C stereomicroscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) to observe fine structural details. Measurements of morphological traits were then recorded using a ruler and a Mitutoyo Vernier caliper (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kawasaki, Japan). Identification was guided by diagnostic keys and species descriptions in the Flora of Thailand, Volume 10, Part 2 [3], and Volume 14, Part 3 (Passifloraceae) [4]. Key characteristics—such as leaf structure, flower morphology, and inflorescence arrangement—were carefully examined. The identification was performed through the examination of herbarium materials, review of essential taxonomic literature, and comparison with authenticated specimens reported in previous studies [3,4,30,31]. Further verification was achieved using high-resolution digital images of specimens obtained from JSTOR Global Plants (https://plants.jstor.org, accessed on 1 August 2025) and from various herbaria (AAU, BK, BKF, BM, CAL, CMU, E, HN, HNU, K, KKU, L, P, PSU, QBG, SING, VMSU, VNM and VNMN). The accepted scientific names were checked against the Plants of the World Online database [2]. Cultivar names were assigned in accordance with guidelines from the Passiflora Society International (https://passiflorasociety.org; accessed on 1 October 2025).

2.4. Plant Specimen Preservation

Specimens (Boonma and Phimpha PS001 to PS009) were pressed and dried for preservation. After drying, the specimens were deposited at VMSU herbarium (VMSU 20200001, VMSU 20200002, VMSU 20200003, VMSU 20200005, VMSU 20200007, VMSU20200008, VMSU 20200009, VMSU 20200014, and VMSU 20200015).

2.5. Study of Ecology

Ecological information was obtained during field investigations of Passifloraceae species conducted in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, Eastern Thailand. The plant species identified in forested areas are listed along with their corresponding forest types. In addition, cultivated plants, especially those grown for various purposes in home gardens, were also documented [29].

2.6. Study of Phenology

This study investigates the phenology of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province. The study emphasized the flowering and fruiting patterns of the species. Months were coded numerically, with 1 representing January and 12 representing December. Monitoring reproductive development helps assess the species’ reproductive capacity and economic potential [29].

2.7. Ethnolinguistic Analysis of Local Plant Names

The analysis of local plant names was carried out following the framework proposed by Wongwattana [32], who explained that Thai plant nomenclature reflects idealized cognitive models related to Thai people’s perceptions and practices toward plants. These folk conceptualizations are shaped by natural and physical environments, socio-cultural lifestyles, and lived experiences. Wongwattana further identified that plant names convey meanings on three levels: proper meaning, metonymical meaning, and metaphorical meaning. Metonymical meanings often refer to attributes such as place of origin, prominent plant parts, color, ownership, symptoms or characteristics, shape, size, scent, purpose, taste, internal texture, surface condition, patterns, quantity or grouping, age or life stage, sex, weight, processing methods, quality, and temperature. Metaphorical meanings involve comparisons to animals or animal parts, materials or objects, humans or human body parts, other plant species, waste products, natural phenomena, behaviors of humans or animals, auspicious qualities, food, and dwellings or constructions. The study applied this framework to organize and interpret local plant names within the defined semantic layers, aiming to deepen insight into how language reflects traditional botanical knowledge.

2.8. Study of Utilization

The utilization of Passifloraceae plants in Non Din Daeng District was gathered through interviews with 60 local residents. Participants were equally distributed across the three subdistricts—Non Din Daeng, Som Poi, and Lam Nang Rong—with 10 males and 10 females interviewed in each area. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and gave their consent orally before taking part in the interviews. The questions aimed to gather information on local plant names, the parts of plants used, preparation techniques, and specific applications. Since no personal or sensitive data were collected, obtaining formal ethical approval was deemed unnecessary [29].

2.9. Quantitative Analysis

2.9.1. Species Use Value (SUV)

The SUV was employed to assess the overall significance of each Passifloraceae species to the local communities in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province. The Use Value (UV) of each species for every use category was calculated across all informants using the following formula [33,34]:

where

- UVi,j = Use value of a species for category j based on informant i’s report

- URi,j = The count of use mentions for the species in category j by informant i

- N = Total number of informants interviewed

Subsequently, the SUV for each species was calculated by adding the UV values from all categories of use:

where C = Total number of use categories, and UVj = Sum of UVs for all informants in category j.

This approach allows the assessment of both category-specific importance and the overall cultural and practical significance of each species within the community.

2.9.2. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) [35]

The RFC was used to evaluate the prominence of individual Passifloraceae species within the community. The RFC was calculated as follows:

RFC = FC/N

In this calculation, FC refers to the number of informants who mentioned a given Passifloraceae species, while N represents the total number of participants. The resulting RFC scores range between 0 and 1, with higher values reflecting a species’ greater cultural or utilitarian importance. This metric enabled the ranking of Passifloraceae plants based on their relative significance in local use. To interpret the RFC values in terms of the degree of recognition among the local community, we applied the following thresholds: RFC ≥ 0.75 was considered “well-known” or “widely known”; RFC between 0.25 and 0.74 was considered “moderately known”; and RFC ≤ 0.24 was considered “less known” or “rarely cited.”

2.9.3. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic)

The Fic was applied to evaluate how consistently informants cited the same plant species for similar medicinal purposes. The resulting scores range from 0 to 1, where values approaching 1 indicate strong agreement among participants regarding the therapeutic use of specific plants. A high Fic value reflects shared traditional knowledge and suggests that a species is well recognized within the community for its medicinal role [36,37]. The Fic was determined using the following equation:

where nur represents the total number of use reports recorded for all plant species associated with a particular ailment or disease category, and nt denotes the number of different plant species reported for that same condition. This index helps evaluate the consistency and reliability of traditional medicinal knowledge, as well as the degree to which certain plants are recognized and accepted within the community. In this study, herbal medicines were classified covers 17 principal therapeutic groups following the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) [38].

Fic = (nur − nt)/(nur − 1)

2.9.4. Fidelity Level (%FL)

The Fidelity Level index was applied to identify plant species most valued for their potential in treating ailments linked to particular disease categories. Because several species can be employed for the same condition, this index indicates which plants are most frequently preferred by informants [39]. The %FL was determined using the following formula:

where Ip represents the number of citations referring to the use of a specific plant species for a particular ailment, and Iu denotes the total number of use reports for that species across all disease categories. A higher %FL value indicates a greater preference for that plant in managing a specific condition, suggesting its perceived therapeutic importance within the community.

%FL = (Ip/Iu) × 100

2.9.5. Economic Values (EV)

The economic value of Passifloraceae species was assessed to determine how these plants contribute to the livelihoods and income of local communities in the study area. The evaluation considered the ways in which the cultivation, sale, and use of these plants generate economic benefits for community members. Price data were collected each month over a one-year period (April 2024 to March 2025) from vendors selling Passifloraceae species in the study area, and the following formula [40] was used to calculate the annual economic value:

where AP represents the average price per kilogram (THB/kg), SM is the total quantity sold each month (kg), and SP indicates the number of months the species was sold during the year. This calculation provides an estimate of the total annual income generated from the sale of each plant species.

EV = AP × SM × SP

2.10. Conservation Status

The authors assessed the conservation status of Passifloraceae species in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, based on the IUCN Red List criteria [41,42].

3. Results

In this study, the specimens of passionfruit known locally as Bak Kathokrok, Mhak Kathokrok, or Saowarot in Non Din Daeng District correspond morphologically to the yellow-fruited form commonly referred to as P. edulis f. flavicarpa O.Deg. The dark purple part of the flower crown and the glossy, large fruits further support this identification. Although this form name is now treated as a synonym of P. edulis Sims [2], it is retained here informally for horticultural clarity, following common usage in the literature [43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. It should be noted that the rosy to purple fruit color is not a reliable criterion to distinguish the two forms, as purple coloration has been transferred from the edulis form to the flavicarpa form by introgression. This characteristic must be maintained through continuous selection, as discussed further in this study.

While the cultivated plant Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’ follows the registration of cultivar names listed in Passiflora Cultivars 2004–2010 (Registration Ref. #133, dated 14 September 2008) [50]. According to the registration record, the cultivar name is P. ‘Soi Fah’, with the originator or breeder unknown. Its presumed parentage is P. caerulea × P. laurifolia (uncertain) [50].

In Thailand, two taxa with red flowers are known: Passiflora ‘Lady Margaret’ [51], which was not found in the study area of Non Din Daeng District, and Passiflora species known as ‘Srimala’, which is present in the study area. After careful examination of the morphological characteristics of the specimens with red flowers in this study, they were found to match P. miniata Vanderpl. [7]. Therefore, in this study, these plants are identified as P. miniata.

The Passiflora species that has naturalized throughout Thailand and was previously identified as P. foetida L. was examined in this study, and the specimen from Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, was confirmed to correspond to P. vesicaria L., particularly based on its yellowish-orange ripe fruits [31,52].

3.1. Diversity of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District

A total of nine taxa of Passifloraceae were recorded in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, comprising two native and seven introduced taxa. The native taxa, Adenia heterophylla and A. viridiflora, were observed both in the wild and under cultivation. Among the introduced taxa, six (Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. miniata, P. trifasciata, Turnera subulata, and T. ulmifolia) were confined to cultivation, whereas P. vesicaria was recorded as naturalized (Figure 2, Table 1), and key to nine taxa are provided (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Passifloraceae species in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province: (a) Adenia heterophylla (Blume) Koord.; (b) A. viridiflora Craib; (c) Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’; (d) P. edulis f. flavicarpa O.Deg.; (e) P. miniata Vanderpl.; (f) P. trifasciata Lem.; (g) P. vesicaria L.; (h) Turnera subulata Sm.; (i) T. ulmifolia L.; (j) Habits of P. vesicaria with fruits; (k) Habit of P. trifasciata. Photographs and design by Thawatphong Boonma.

Table 1.

Diversity of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province.

Table 2.

Key to nine taxa of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province.

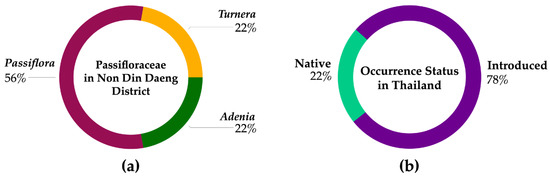

The species diversity of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, comprises nine taxa across three genera. These include Adenia heterophylla (Blume) Koord., A. viridiflora Craib, Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa O.Deg., P. miniata Vanderpl., P. trifasciata Lem., P. vesicaria L., Turnera subulata Sm., and T. ulmifolia L. Among the three genera, Passiflora (five taxa, 56%) exhibits greater species diversity than the others (Figure 3). Two species of Adenia (A. heterophylla and A. viridiflora), representing 22%, are native to Thailand and occur both in the wild and under cultivation. In contrast, the remaining taxa are introduced.

Figure 3.

Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng, Buri Ram Province: (a) Percentage of diversity in each genus; (b) Occurrence status in Thailand of taxa found in Non Din Daeng, Buri Ram Province.

3.2. Ecology of Passifloraceae Plants in Non Din Daeng

Two species, Adenia heterophylla and A. viridiflora, are native and occur both in natural and cultivated habitats. A. heterophylla was found in deciduous forest and cultivated areas, while A. viridiflora occurred in mixed deciduous forest and cultivated sites. The remaining taxa are introduced, with Passiflora vesicaria naturalized and P. ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. miniata, P. trifasciata, Turnera subulata, and T. ulmifolia confined to cultivation. Most taxa in the district are introduced and primarily associated with cultivated habitats, whereas native species persist in deciduous and mixed deciduous forest environments.

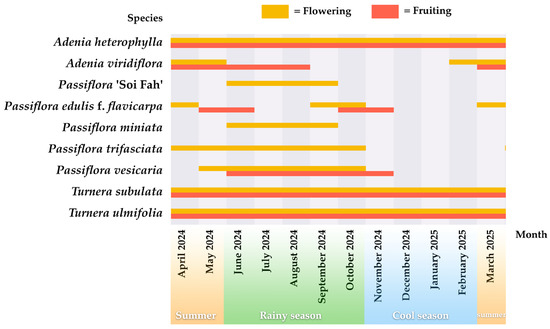

3.3. Flowering and Fruiting Period of Passifloraceae Plants in Non Din Daeng

Flowering of Passifloraceae taxa in Non Din Daeng District varied among species. Adenia heterophylla flowered throughout the year, while A. viridiflora bloomed from February to May. Cultivated species such as Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’ and P. miniata flowered during June to September. P. edulis f. flavicarpa showed two flowering periods, in March–April and September–October. The naturalized P. vesicaria flowered from May to October, and P. trifasciata from April to October. Turnera subulata and T. ulmifolia produced flowers throughout the year. Fruiting periods followed similar patterns. Adenia heterophylla and both Turnera species fruited year-round, while A. viridiflora fruited from March to August. P. edulis f. flavicarpa produced fruits during May–June and October–November, and P. vesicaria from June to November. Fruiting was not observed in P. ‘Soi Fah’, P. miniata, and P. trifasciata.

Based on the field observations, the flowering and fruiting of Passifloraceae taxa in Non Din Daeng District can be summarized according to the three distinct seasons of the region as follows:

Winter (November–February): Adenia heterophylla, Turnera subulata, and T. ulmifolia flowered year-round, while A. viridiflora began flowering in February. Fruit production during this season was observed in A. heterophylla and both Turnera species, whereas A. viridiflora fruited from March onward.

Summer (March–May): Flowering peaked for A. viridiflora and P. edulis f. flavicarpa. While P. trifasciata and P. vesicaria also initiated flowering. Fruiting occurred in A. viridiflora, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. vesicaria, A. heterophylla, and the two Turnera species. Cultivated species P. ‘Soi Fah’ and P. miniata did not produce fruits.

Rainy season (June–October): Flowering continued for P. vesicaria, P. trifasciata, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. ‘Soi Fah’, and P. miniata. Fruiting occurred in P. vesicaria during the rainy season and P. edulis f. flavicarpa toward the end of the season, while A. heterophylla and both Turnera species fruited year-round. Fruiting was not observed in P. ‘Soi Fah’, P. miniata, or P. trifasciata. This seasonal pattern indicates that species respond differently to climatic conditions, with some taxa flowering and fruiting year-round, while others are restricted to specific seasons (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Flowering and fruiting periods of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng, Buri Ram Province.

3.4. Ethnolinguistic Analysis of Vernacular Plant Names

In Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, Eastern Thailand, nine taxa of Passifloraceae were recorded under a total of 12 vernacular names (Table 3). Analysis of these names following Wongwattana’s framework [32] revealed three types of meaning: proper, metonymical, and metaphorical. Proper meanings were the most frequent, accounting for six vernacular names (50% of the total). These include Adenia viridiflora (“Phak E-Noon” and “Phak Sarb”), Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa (“Bak Kathokrok”; “Mhak Kathokrok”; and “Saowarot”), and P. miniata (“Sri Mala”). These names denote the plant itself or its recognized identity, reflecting straightforward naming based on the species. Metonymical meanings were observed in three names (25%), including P. ‘Soi Fah’ (“Soi Fah”), Turnera subulata (“Barn Chaow Si Nuan”), and T. ulmifolia (“Barn Chaow Lueang”). These names highlight a notable feature or association of the plant, such as flower color or flowering time. Metaphorical meanings were recorded in three names (25%), including A. heterophylla (“Kim Jeng”), P. trifasciata (“Teen Dinosao”), and P. vesicaria (“Tamlueng Thong”). These names employ figurative or symbolic references, reflecting local perceptions or cultural associations of the plants. An illustrative example from outside the local context is the genus name Passiflora, from which the family name Passifloraceae is derived. Passiflora comes from the Latin words: passus (“suffering”) and flos (“flower”) and was named the “Flower of the Passion” by Spanish priests in Mexico because its floral structures were interpreted symbolically to represent the crucifixion of Christ. According to tradition, the three stigmas represent the three nails; the crown of filaments represents the crown of thorns; the five petals and five sepals symbolize the ten apostles who remained faithful to Jesus Christ; the androgynophore recalls the column of the flagellation; the tendrils represent the scourges; and the five anthers represent the five wounds. Legends recount other imaginative and suggestive analogies. This example demonstrates how plant names, even at the genus level, can encode rich cultural and symbolic meanings [53].

Table 3.

Vernacular names of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, with their proper, metonymical, and metaphorical meanings.

The predominance of proper meanings indicates a tendency in local vernacular naming to label plants based on direct recognition, while metonymical and metaphorical names reveal cultural interpretations and symbolic significance. This analysis underscores the value of vernacular names as a source of ethnobotanical knowledge, providing insights into how local communities perceive, categorize, and relate to plant species.

3.5. Traditional Uses of Passifloraceae Plants in Non Din Daeng

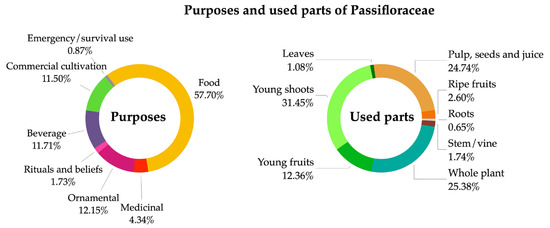

In Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, nine taxa from three genera of Passifloraceae were recorded. All species are utilized for multiple purposes, including food, medicine, ornamental use, commercial cultivation, rituals and beliefs, and emergency or survival use in the wild (Figure 5, Table 4). Plant parts such as young shoots, fruits, stems, roots, and leaves are used according to traditional knowledge, with some species cultivated for practical use or for their role in local rituals and beliefs. Certain taxa are grown commercially for sale of edible parts, while others are maintained primarily for ornamental purposes.

Figure 5.

Some products from Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng: (a) Adenia heterophylla (Blume) Koord. cultivated in a pot to display its bell-shaped caudex, used as an auspicious ornamental plant; (b) Young fruits of A. viridiflora Craib are sold at the Non Din Daeng market; (c) Mature fruits of Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa O.Deg. are bagged and sold at roadside stalls along the Non Din Daeng–Ta Phraya route; (d) Saowarot crispy noodles, an iconic specialty of Non Din Daeng District, made using juice from P. edulis f. flavicarpa. Photographs by Thawatphong Boonma.

Table 4.

Traditional uses of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province.

Regarding the purposes of use, Passifloraceae species were utilized for multiple functions in the study area, with a total of eight categories reported (Figure 6). The highest proportion of use reports was for food purposes, accounting for 57.70% of all reports, followed by ornamental use (12.15%), beverages (11.71%), commercial cultivation (11.50%), medicinal use (4.34%), rituals and beliefs (1.73%), and emergency/survival use (0.87%).

Figure 6.

Proportion of use reports for different purposes and used parts of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng.

A total of eight plant parts of Passifloraceae were reported as being used, with varying frequencies. Young shoots were the most frequently utilized part, with 145 use reports (31.45%), followed by the whole plant (117 reports, 25.38%). Pulp, seeds and juice (114 reports, 24.74%). Young fruits were reported in 57 cases (12.36%), ripe fruits in 12 (2.60%), stems or vines in 8 (1.74%), leaves in 5 (1.08%), and roots in 3 (0.65%). These results indicate a strong preference for harvesting aerial parts, particularly young shoots and reproductive structures, rather than subterranean parts such as roots.

3.5.1. Species Use Value (SUV) of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng

The SUV of the nine Passifloraceae taxa ranged from 0.050 to 2.800 (Table 5). The highest SUV was recorded for Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa (2.800), followed by Adenia viridiflora (1.484), A. heterophylla (0.316), and P. trifasciata (0.267). Two taxa, P. vesicaria and Turnera ulmifolia, had SUV values of 0.250. P. ‘Soi Fah’ had a SUV of 0.117, T. subulata had a SUV of 0.100, and P. miniata showed the lowest SUV (0.050).

Table 5.

Category-specific use values (UV), Species Use Values (SUV), and Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng, Buri Ram Province.

Food use: Only three species were recorded for food use. Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa and Adenia viridiflora had the highest food use values (UVFood = 1), indicating their significance as edible plants in the study area. P. vesicaria showed moderate use for food (UVFood = 0.250), while the remaining species were not utilized for this purpose.

Beverage use: Beverage use was limited to a single species, Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa (UVBeverage = 0.900), highlighting its importance in local beverage preparation. All other species had no recorded use as beverages.

Medicinal use: Medicinal applications were observed in a few species. Adenia viridiflora (UVMedicinal = 0.167) and Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa (UVMedicinal = 0.117) were the main species used for traditional medicine, whereas other taxa had minimal or no medicinal value.

Ornamental use: Ornamental use was the most common category among the recorded taxa. Passiflora trifasciata had the highest ornamental value (UVOrnamental = 0.267), followed by Adenia heterophylla (0.183) and Turnera ulmifolia (0.217). Other species such as P. ‘Soi Fah’ (0.117), T. subulata (0.100), and P. miniata (0.050) also contributed to ornamental use, though to a lesser extent.

Rituals and beliefs: Only Adenia heterophylla was recorded as being used in rituals or cultural practices (UVRituals = 0.133), while all other species had no known applications in this category.

Emergency/survival use: Emergency or survival use was limited to Adenia viridiflora (UV = 0.067), by collecting water from cut stems when no water source is available in the wild, with no other species recorded for this purpose.

Commercial cultivation: Commercial cultivation was significant for Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa (UV = 0.633) and Adenia viridiflora (0.250), reflecting their economic importance. The remaining species were not cultivated commercially.

Considering all categories, Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa and Adenia viridiflora had the highest overall use values (SUV = 2.800), indicating their multifaceted importance to local communities. Other taxa had lower SUV scores, mainly reflecting ornamental or minor uses (Table 4).

Among the seven use categories recorded, food use showed the highest overall utilization value (ΣUV = 2.250), followed by commercial cultivation (ΣUV = 1.033) and ornamental use (ΣUV = 0.934). Other categories such as beverage, medicinal, rituals and beliefs, and emergency/survival use exhibited comparatively lower values. These results indicate that edible and economically valuable species, particularly those in the genus Passiflora, represent the most significant use group among Passifloraceae plants in Non Din Daeng District.

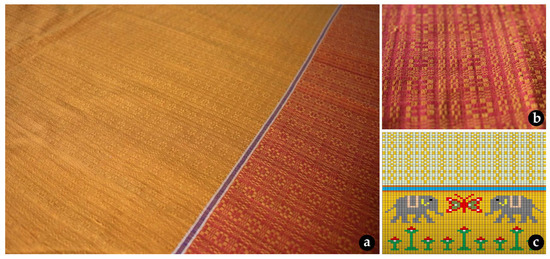

Additionally, another point worth noting in this study is that, although there is no direct use of the plant, it is widely recognized by the local community in Non Din Daeng District through the “Sri Saowarot Kotchasan” fabric pattern (Figure 7), where Sri signifies the dignity of the people of Non Din Daeng, who protected the land from communist insurgents that obstructed the construction of the Lahan Sai–Non Din Daeng–Ta Phraya route; Saowarot refers to the fruit of P. edulis f. flavicarpa, the district’s top economic crop and a local symbol; and Kotchasan represents the wild elephants inhabiting the surrounding hills. The fabric is made of silk and produced using the traditional tie-dye weaving technique (Mudmee), with the pattern designed by Suwithoon Prasertsri. Using traditional weaving methods, the design reflects local identity and knowledge related to agriculture and community life, adds value to local products, and contributes to the sustainable preservation of the community’s cultural heritage.

Figure 7.

Sri Saowarot Kotchasan patterned fabric: (a) overview of the Sri Saowarot Kotchasan patterned fabric; (b) close-up showing the passion fruit flower motif; (c) detail of the Sri Saowarot Kotchasan pattern. Photograph courtesy of the Buriram Provincial Cultural Office.

3.5.2. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng

The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) values of the nine Passifloraceae taxa in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, ranged from 0.050 to 1.000 (Table 4). The highest RFC values (1.000) were recorded for Adenia viridiflora and Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa, indicating that all informants cited these species. This suggests that these two species are widely known and culturally important within the community. Moderate RFC values were observed for A. heterophylla (0.283), P. trifasciata (0.267), P. vesicaria (0.217), and T. ulmifolia (0.217), reflecting fairly frequent recognition and use. Lower RFC values were found for T. subulata (0.100), P. ‘Soi Fah’ (0.117), and P. miniata (0.050), suggesting that these species are less known or used less frequently by the local people. Higher RFC values indicate greater prominence and familiarity of a species within the local community, whereas lower values reflect limited recognition or utilization.

3.5.3. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) of Passifloraceae Used as Medicinal Plants

The traditional use notes recorded in this study were categorized according to the 17 main system categories [38]. Among these, seven medical categories were represented in the dataset: Central nervous system, Endocrine system, Gastro-intestinal system, Infections, Nutrition and blood, Obstetrics, gynaecology and urinary-tract disorders, and Skin (Table 6).

Table 6.

Informant consensus factor (Fic) of Passifloraceae used as medicine in Non Din Daeng.

The highest number of use-reports (Nur) was recorded for the Gastro-intestinal system (7 reports, 2 species), with a fidelity level (Fic) of 0.833, indicating high but not complete consensus among informants. Categories with complete agreement among users, showing a Fic of 1.000, included the Central nervous system (5 reports, 1 species), Endocrine system (2 reports, 1 species), Infections (2 reports, 1 species), Nutrition and blood (4 reports, 1 species), and Obstetrics, gynaecology and urinary-tract disorders (2 reports, 1 species). The Skin category accounted for 4 use-reports across 2 species, with a slightly lower Fic of 0.667, reflecting moderate agreement among respondents. These findings highlight the predominant use of medicinal plants for gastrointestinal, neurological, metabolic, and dermatological purposes within the studied communities.

3.5.4. Fidelity Level (%FL) of Passifloraceae Used as Medicine in Non Din Daeng

The Fidelity Level (%FL) analysis revealed that Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa had the highest specific medicinal use agreement among informants, with a %FL of ≈55.556% for treating fever, followed by equal values of ≈22.222% each for use as an anthelmintic and for treating itchy rashes. Adenia viridiflora showed a highest %FL of ≈45.455% for relieving diarrhea, with additional uses for nourishing the liver (≈27.273%), relieving difficulty in urination (≈18.182%), and nourishing blood for postpartum women (≈9.091%). Turnera ulmifolia exhibited an equal %FL of ≈33.333% across three reported uses: treatment of diabetes, chronic gastrointestinal conditions and ulcers, and wound healing (Table 7).

Table 7.

Fidelity Level (%FL) of Passifloraceae used as medicine in Non Din Daeng.

When grouped by medical categories, the gastro-intestinal system showed the highest overall fidelity values (≈45.455% and ≈33.333% from A. viridiflora and T. ulmifolia, respectively), followed by the central nervous system (≈55.556% from P. edulis f. flavicarpa). Other categories with moderate values included nutrition and blood (≈27.273% and ≈9.091%), skin (≈33.333% and ≈22.222%), infections (≈22.222%), endocrine system (≈33.333%), and obstetrics, gynaecology and urinary-tract disorders (≈18.182%). These results indicate that Passifloraceae species in Non Din Daeng are most frequently and consistently used for treating gastrointestinal and systemic conditions such as fever and digestive disorders.

3.5.5. Economic Values (EV) of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng

A total of three Passifloraceae products from two species were cultivated for commercial purposes in Non Din Daeng between 1 April 2024 and 31 March 2025 (Table 8). Adenia viridiflora was traded both as young shoots, with or without flowers, and as immature fruits. The price of young shoots ranged from 100 to 150 THB/kg, available throughout the year (January–December), with a monthly sales volume of 100 kg, generating an average yearly income of 150,000 THB per trader. Immature fruits were sold at 100–120 THB/kg during March–August, with a monthly sales volume of 300 kg, yielding an average yearly income of 198,000 THB per trader. Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa was traded as mature fruits at 20–35 THB/kg, primarily during May–June and October– November, with a monthly sales volume of 1000 kg and an average yearly income of 110,000 THB per trader. The actual income obtained from these crops depends on the cultivated area; in this study, calculations were made based on a standard unit of 1 rai (approximately 0.16 hectares).

Table 8.

Passifloraceae species grown for commercial use, showing their price ranges, periods of trade, monthly sales quantities, and average annual income per vendor in Non Din Daeng (1 April 2024 to 31 March 2025).

Cultivation of Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa begins with seed germination, which takes about 1–2 months before the seedlings can be transplanted into the field. The recommended planting distance is 3 × 3 m, allowing approximately 180 plants per 0.16 hectares, with bamboo poles used as support structures. During the initial stage, watering should be carried out once a week, and during the rainy season, watering can be reduced or stopped. However, yield depends on weather conditions, during severe drought, production may decrease, making an adequate irrigation system necessary. The plants start producing fruit 6–8 months after transplanting. Selective breeding has since increased the proportion of purple fruits and larger fruit size, as larger fruits fetch higher prices. After harvesting, continuous planting in the same area reduces yield and depletes soil nutrients. Therefore, crop rotation with other plants, such as cassava, is recommended for at least two years before replanting P. edulis f. flavicarpa. In contrast, Adenia viridiflora can be cultivated using similar methods and can produce for several years without needing to be uprooted, allowing continuous harvests. Moreover, due to its high yield and good market value, both young fruits and young shoots can be harvested, making A. viridiflora an attractive alternative crop.

3.5.6. Proposal of Conservation Status of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng

A total of nine Passifloraceae taxa were recorded in Non Din Daeng District, comprising two native Adenia species and seven introduced or naturalized species, including Passiflora and Turnera species (Table 1). According to the IUCN Red List, most species were not evaluated (NE), except for T. ulmifolia, which is listed as Least Concern (LC). Based on the authors’ assessment, A. heterophylla is proposed as Near Threatened (NT) due to ongoing extraction of wild individuals from forests in other provinces for online sale. In contrast, A. viridiflora, although native and cultivated, is considered of Least Concern (LC) because current propagation relies on stem cuttings rather than direct removal from natural populations. Among the introduced species, P. vesicaria is naturalized, while the others—P. ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. miniata, P. trifasciata, T. subulata, and T. ulmifolia—are cultivated. All introduced and naturalized species were assessed as LC, except for P. ‘Soi Fah’, which is Data Deficient (DD), reflecting their established presence in cultivation or naturalized habitats without significant threats.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first systematic documentation of Passifloraceae diversity and uses in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, recording nine taxa across three genera and providing new locality data for eastern Thailand [3,4]. Both native species (Adenia heterophylla, A. viridiflora) and introduced taxa (Passiflora spp.) were recorded, reflecting natural distribution and human-mediated introduction, consistent with patterns elsewhere in Southeast Asia [3,4].

Previous records listed Passiflora foetida L. as an introduced and naturalized species [3,4]; however, specimens from Non Din Daeng District correspond to P. vesicaria L., which has ovoid to globose fruits that mature to deep yellow orange—a key trait distinguishing it from P. foetida [31]. This study provides the first confirmed record of the introduction and naturalization of P. vesicaria in Thailand.

Among the taxa documented, Adenia heterophylla and A. viridiflora are newly recorded for Buri Ram Province, while Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. miniata, P. trifasciata, P. vesicaria, Turnera subulata, and T. ulmifolia represent new provincial records. Native species occurred mainly in dry dipterocarp and mixed deciduous forests, whereas introduced species were concentrated in cultivated areas, consistent with Passiflora’s tendency to establish in disturbed habitats [9,10,11,12,13]. The naturalization of P. vesicaria in open secondary forests further demonstrates its ecological adaptability [4,20].

The phenological patterns of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District appear to correspond closely with the region’s tropical savanna (Aw) climate [27]. The climate includes three main periods: a cool season from November to February, a hot season from March to May, and a rainy season spanning June to October. During the study period, general temperatures ranged from 19 °C to 35 °C, with January 2025 being the coolest month (13 °C) and late April 2024 the hottest (44 °C), rarely falling below 15 °C or exceeding 38 °C, and mean annual temperatures of 27–28 °C. Annual rainfall from April 2024 to March 2025 was about 164 mm, concentrated mainly in the rainy season. Under these climatic conditions, Adenia heterophylla and both Turnera species (T. subulata and T. ulmifolia) flowered and fruited year-round, reflecting adaptation to stable warmth and moderate moisture. A. viridiflora flowered from February to May and fruited from March to August, spanning the transition from the cool to the early rainy season. Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa exhibited two distinct flowering peaks—in March–April, before the onset of monsoon rains, and again in September–October, during the late rainy season—and fruited in May–June and October–November, suggesting responsiveness to changing rainfall and temperature regimes. P. vesicaria flowered from May to October and fruited from June to November, aligning with the warm and humid conditions of the rainy season. In contrast, P. ‘Soi Fah’ [50], P. miniata [7], and P. trifasciata flowered but produced no fruits during the study period. These observations indicate that the alternation between dry and wet seasons, combined with temperature fluctuations, plays a crucial role in regulating flowering and fruiting phenology of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District.

Vernacular naming revealed a predominance of descriptive names, suggesting close familiarity of local communities with these plants, while metonymical and metaphorical names highlight cultural associations. Such patterns are typical of ethnolinguistic traditions in Thailand and neighboring regions, where plant names reflect both morphological and symbolic attributes [32].

Food use was the primary purpose of Passifloraceae utilization, followed by ornamental, beverage, and commercial uses, consistent with the known economic and nutritional value of P. edulis f. flavicarpa and related species [3,4,5,6]. The high Species Use Value (SUV) and Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of P. edulis f. flavicarpa and A. viridiflora indicate their cultural and economic importance. Notably, A. viridiflora demonstrated versatile applications, including edible, medicinal, and emergency uses, reflecting broad ethnobotanical relevance as documented for the genus Adenia in Asia and Africa [9,11].

Medicinal applications were concentrated on gastrointestinal, neurological, and metabolic treatments, with high Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) values indicating well-established traditional knowledge. The Fidelity Level (%FL) analysis highlighted species-specific cultural preferences, supporting the ethnomedical significance of these taxa and aligning with pharmacological studies reporting anxiolytic, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory properties of Passiflora and Adenia species [21,22,23,24,25,26].

Economic analysis demonstrated that P. edulis f. flavicarpa and A. viridiflora provide substantial income for local households through continuous or seasonal harvests. Their cultivation and trade practices align with national horticultural standards for Passiflora, emphasizing sustainable production [3]. Although cultivation appears to rely mainly on locally propagated materials rather than wild collection, this observation is based on limited field evidence. Further source tracking and long-term monitoring are needed to confirm that cultivation does not negatively affect natural populations. Moreover, the integration of these species into cultural expressions, such as the “Sri Saowarot Kotchasan” textile design, underscores their sociocultural relevance.

From a conservation perspective, Adenia heterophylla was proposed as Near Threatened due to its limited populations and habitat disturbance. Although wild populations in Buri Ram Province appear relatively undisturbed, online market surveys revealed continuous harvesting from natural habitats in other provinces for ornamental trade. The species is highly valued for its caudiciform (bell-shaped) stem, and because cultivated plants require many years to develop large caudices, traders often extract mature individuals directly from the wild, posing conservation risks. In contrast, cultivated and naturalized Passiflora species were considered of Least Concern [41,42]. Promoting community-based cultivation, propagation programs, and public awareness could help reduce harvesting pressure and support sustainable use of native taxa.

The findings highlight the ecological, cultural, and economic significance of Passifloraceae in Non Din Daeng District. Future research should focus on phytochemical and pharmacological studies, long-term monitoring of naturalized species like P. vesicaria, and detailed socio-economic assessments of plant use and trade. Integrating ethnobotanical knowledge with conservation and sustainable management strategies will be crucial for protecting native species while supporting rural livelihoods in Thailand and Southeast Asia [3,14,15,16,20].

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first systematic documentation of Passifloraceae diversity and ethnobotany in Non Din Daeng District, Buri Ram Province, recording nine taxa across three genera and contributing several new distribution records. Among these, two native species—Adenia heterophylla and A. viridiflora—are newly recorded for Buri Ram Province, while seven taxa—Passiflora ‘Soi Fah’, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. miniata, P. trifasciata, P. vesicaria, Turnera subulata, and T. ulmifolia represent new provincial records. Native species were primarily associated with dry dipterocarp and mixed deciduous forests, whereas introduced taxa were concentrated in cultivated or disturbed areas, reflecting ecological adaptability and human-mediated introduction. Ethnobotanical analyses revealed multiple uses including food, ornamental, beverage, commercial, medicinal, and emergency purposes with P. edulis f. flavicarpa and A. viridiflora having particularly high cultural and economic importance. Conservation assessments indicate that A. heterophylla may be threatened by wild harvesting for ornamental trade, while cultivated and naturalized Passiflora species are of Least Concern. These findings underscore the value of integrating traditional knowledge with sustainable cultivation and community-based management to conserve native species, support livelihoods, and guide future research on phytochemistry, pharmacology, and conservation of Passifloraceae in Thailand and Southeast Asia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., T.B., S.P., A.J., W.P.O. and S.S.; methodology, P.S., T.B., S.P., A.J., W.P.O. and S.S.; software, T.B.; validation, P.S., T.B., S.P., A.J., W.P.O. and S.S.; formal analysis, P.S., T.B., S.P., A.J., W.P.O. and S.S.; investigation, T.B. and S.P.; resources, T.B. and S.P.; data curation, T.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.B.; writing—review and editing, P.S., T.B., S.P., A.J., W.P.O. and S.S.; visualization, T.B.; supervision, P.S., A.J. and S.S.; project administration, S.S. and T.B.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mahasarakham University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with all relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines. The research involved only verbal interviews to document traditional knowledge, including local plant names, utilized plant parts, preparation techniques, and uses, without collecting personal, medical, or sensitive information. The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Mahasarakham University, and all authors completed Human Subject Protection (HSP) training certified by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were informed of their rights, including voluntary participation and the option to withdraw at any time. The study adhered to the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE) Code of Ethics and the principles of the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing. Ethical review and approval were waived for plant collection, which complied with national legislation, did not involve protected areas, and required no specific permits.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Mahasarakham University for financial support, particularly the Division of Research Facilitation and Dissemination. We are also grateful for the laboratory and microscope facilities provided by the Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute. Our appreciation extends to Saman Phimpha, Wilailak Phimpha, and Chatchayapa Phimpa for their assistance during our fieldwork. The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to the local residents and communities in Non Din Daeng District for their generous cooperation, valuable information, and kind support during the field investigation. We also acknowledge the invaluable support of the curators of the herbarium collections we visited. We additionally thank the Buriram Provincial Cultural Office and the Buri Ram Community Development Provincial Office for providing support and the photograph of the Sri Saowarot Kotchasan patterned fabric. We dedicate this work to the late Suwithoon Prasertsri, the designer of the Sri Saowarot Kotchasan patterned fabric, inspired by the passion fruit flower, an important economic plant of Non Din Daeng District, in recognition of her creative contribution and lasting legacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAU | Aarhus University Herbarium, Aarhus University, Denmark |

| BK | Bangkok Herbarium, Department of Agriculture, Bangkok, Thailand |

| BKF | The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok, Thailand |

| BM | Natural History Museum Herbarium, London, United Kingdom |

| CAL | Calicut University Herbarium, University of Calicut, Kerala, India |

| CMU | Chiang Mai University Herbarium, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| E | Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh Herbarium, Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| HN | Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), Hanoi, Vietnam |

| HNU | VNU University of Science, Hanoi, Vietnam |

| K | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Herbarium, Richmond, Surrey, United Kingdom |

| KKU | Khon Kaen University Herbarium, Khon Kaen, Thailand |

| L | National Herbarium Nederland, Leiden University Branch, Leiden, Netherlands |

| P | Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France |

| PSU | Prince of Songkla University Herbarium, Hat Yai Songkhla, Thailand |

| QBG | Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden Herbarium, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| SING | Singapore Botanic Gardens Herbarium, Singapore |

| VMSU | Vascular Plant Herbarium, Mahasarakham University, Thailand |

| VNM | Institute of Tropical Biology, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam |

| VNMN | Vietnam National Museum of Nature, Hanoi, Vietnam |

References

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- de Wilde, W.J.J.O.; Duyfjes, B.E.E. Passifloraceae. In Flora of Thailand; Smitinand, T., Nuyim, T., Eds.; The Forest Herbarium, Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010; Volume 10, Part 2; pp. 236–257. [Google Scholar]

- Suddee, S. Passifloraceae (Part 2). In Flora of Thailand; Santisuk, T., Chayamarit, K., Balslev, H., Eds.; Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; Volume 14, Part 3; pp. 506–509. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, J.; Coppens d’Eeckenbrugge, G. Morphological Characterization in the Genus Passiflora L.: An Approach to Understanding Its Complex Variability. Plant Syst. Evol. 2017, 303, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thokchom, R.; Mandal, G. Production Preference and Importance of Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis): A Review. J. Agric. Eng. Food Technol. 2017, 4, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderplank, J. 562. Passiflora miniata. Curtis’s Bot. Mag. 2006, 23, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, P.P.; Souza, M.M.; Santos, E.A.; Silva, L.C.; Britto, F.B.; Oliveira, E.J. Passion Flower Hybrids and Their Use in the Ornamental Plant Market: Perspectives for Sustainable Development with Emphasis on Brazil. Euphytica 2009, 166, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouafon, I.L.; Katerere, D.R. Review of the Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicity Studies of the Genus Adenia. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1581659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeira, J.M.; Fenner, R.; Betti, A.H.; Provensi, G.; Lacerda, L.d.A.; Barbosa, P.R.; González, F.H.; Corrêa, A.M.; Driemeier, D.; Dall’Alba, M.P.; et al. Toxicity and Genotoxicity Evaluation of Passiflora alata Curtis (Passifloraceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, M.; Biscotti, F.; Zanello, A.; Polito, L.; Bolognesi, A. Heterophyllin: A New Adenia Toxic Lectin with Peculiar Biological Properties. Toxins 2024, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Patra, J.K. Passiflora foetida L.: An Exotic Ethnomedicinal Plant of Odisha, India. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 1, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, L.R.; Rodrigues, R.A.; Ramos, A.S.; da Cruz, J.D.; Ferreira, J.L.P.; Silva, J.R.A.; Amaral, A.C.F. Herbal Medicinal Products from Passiflora for Anxiety: An Unexploited Potential. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 6598434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Krosnick, S.E.; Jørgensen, P.M.; Hearn, D. Passifloraceae. In Flora of China; (Clusiaceae through Araliaceae); Wu, Z.Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.Y., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2007; Volume 13, p. 141. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=10656 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Nguyen, B.T. Checklist of Plant Species of Vietnam; Agriculture Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001–2005; Volume 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wannasaksri, W.; Temviriyanukul, P.; Aursalung, A.; Sahasakul, Y.; Thangsiri, S.; Inthachat, W.; On-Nom, N.; Chupeerach, C.; Pruesapan, K.; Charoenkiatkul, S.; et al. Influence of Plant Origins and Seasonal Variations on Nutritive Values, Phenolics and Antioxidant Activities of Adenia viridiflora Craib., an Endangered Species from Thailand. Foods 2021, 10, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saensouk, P.; Ragsasilp, A.; Thawara, N.; Boonma, T.; Appamaraka, S.; Sengthong, A.; Daovisan, H.; Setyawan, A.D.; Saensouk, S. Ethnobotanical Study of Acanthaceae Family in Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. Biodiversitas 2024, 25, 2570–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Boonma, T.; Saensouk, S. Curcuma pulcherrima (Zingiberaceae), a New Rare Species of Curcuma subgen. Ecomata from Eastern Thailand. Biodiversitas 2022, 23, 6635–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Maknoi, C.; Song, D.; Boonma, T. Curcuma nivea (Zingiberaceae), a New Compact Species with Horticultural Potential from Eastern Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neangthaisong, T.; Rattanakiat, S.; Phimarn, W.; Joeprakhon, S.; Saramunee, K.; Sungthong, B. Local Wisdom and Medicinal Plant Utilization of Certified Folk Healers for Therapeutic Purposes in Buriram Province, Thailand. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 5, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, K.; Velikova, M.; Gentscheva, G.; Gerasimova, A.; Slavov, P.; Harbaliev, N.; Makedonski, L.; Buhalova, D.; Petkova, N.; Gavrilova, A. Chemical Compositions, Pharmacological Properties and Medicinal Effects of Genus Passiflora L.: A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justil-Guerrero, H.J.; Arroyo-Acevedo, J.L.; Rojas-Armas, J.P.; García-Bustamante, C.O.; Palomino-Pacheco, M.; Almonacid-Román, R.D.; Calva Torres, J.W. Evaluation of Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Capacity, and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Lipophilic and Hydrophilic Extracts of the Pericarp of Passiflora tripartite var. mollissima at Two Stages of Ripening. Molecules 2024, 29, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Mahendran, D.; Kalimuthu, A.; Ravi, M. The Active Compounds of Passiflora spp. and Their Potential Medicinal Uses from Both In Vitro and In Vivo Evidences. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villada Ramos, J.A.; Aguillón Osma, J.; Restrepo Cortes, B.; Loango Chamarro, N.; Maldonado Celis, M.E. Identification of Potential Bioactive Compounds of Passiflora edulis Leaf Extract against Colon Adenocarcinoma Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 34, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Panaskar, P.; Narayankar, C.; Waghmode, A.; Gaikwad, D. Passiflora, a Promising Medicinal Plant. Sci. Technol. Dev. 2021, 10, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Koriem, K.M.M. Importance of Herba Passiflorae in Medicinal Applications: Review on Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. Biomed. Res. Int. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 12886–12900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen. Earth. Interactive Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps. Available online: https://koppen.earth (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Office of the National Water Resources. Rainfall Data. Available online: https://nationalthaiwater.onwr.go.th/rainfall (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Boonma, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P. Biogeography, Conservation Status, and Traditional Uses of Zingiberaceae in Saraburi Province, Thailand, with Kaempferia chaveerachiae sp. nov. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craib, W.G. Passiflora siamica. Bull. Misc. Inform. Kew 1911, 1, 55–56. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/43464#page/61/mode/1up (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Vanderplank, J. A revision of Passiflora section Dysosmia Passifloraceae. Curtis’s Bot. Mag. 2013, 30, 318–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwattana, U.S. Thai Folk Plant Names: A Study in Ethno-Botanical Linguistics; Chulalongkorn University Press: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B.; Gallaher, T. Importance indices in ethnobotany. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 201. Available online: https://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/130/115 (accessed on 1 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Phillips, O.; Gentry, A.H. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ. Bot. 1993, 47, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Puricelli, C.; Ciuchi, D.; Segale, A.; Fico, G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, R.T.; Logan, M.H. Informant consensus: A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet: Biobehavioral Approaches; Etkin, N.L., Ed.; Redgrave Publishers: Bedford Hills, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- National Drug System Development Committee. National List of Essential Medicines B.E. 2565; Royal Gazette: Hamilton, Bermuda, 2022; Volume 139, Special Issue 182 Ngor. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.; Yaniv, Z.; Dafni, A.; Palewitch, D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Maknoi, C.; Setyawan, A.D.; Boonma, T. A horticultural Gem Unveiled: Curcuma peninsularis sp. nov. (Zingiberaceae), a new species from Peninsular Thailand, previously misidentified as Curcuma aurantiaca Zijp. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, Version 16, 2024. Available online: https://nc.iucnredlist.org/redlist/content/attachment_files/RedListGuidelines.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- IUCN. Guidelines for Application of IUCN Red List Criteria at Regional and National Levels, Version 4.0; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2012; p. iii + 41. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/RL-2012-002.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Macedo, M.C.C.; Correia, V.T.d.V.; Silva, V.D.M.; Pereira, D.T.V.; Augusti, R.; Melo, J.O.F.; Pires, C.V.; de Paula, A.C.C.F.F.; Fante, C.A. Development and Characterization of Yellow Passion Fruit Peel Flour (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa). Metabolites 2023, 13, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Socorro Fernandes Marques, S.; Libonati, R.M.F.; Sabaa-Srur, A.U.O.; Luo, R.; Shejwalkar, P.; Hara, K.; Dobbs, T.; Smith, R.E. Evaluation of the Effects of Passion Fruit Peel Flour (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) on Metabolic Changes in HIV Patients with Lipodystrophy Syndrome Secondary to Antiretroviral Therapy. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.F.S.; Liu, X.; Suddarth, S.R.P.; Nguyen, C.; Sandhu, D. NaCl Accumulation, Shoot Biomass, Antioxidant Capacity, and Gene Expression of Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa Deg. in Response to Irrigation Waters of Moderate to High Salinity. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.M.; Pereira, T.N.S.; Viana, A.P.; Pereira, M.G.; do Amaral Júnior, A.T.; Madureira, H.C. Flower receptivity and fruit characteristics associated to time of pollination in the yellow passion fruit Passiflora edulis Sims f. flavicarpa Degener (Passifloraceae). Sci. Hortic. 2004, 101, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Leon, G.M.; Nunziata, S.; Padmanabhan, C.; Rivera, Y.; Brlansky, R.H.; Hartung, J.S. First report of passion fruit green spot virus in yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) in Casanare, Colombia. Plant Dis. 2023, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R.E.; Wibisana, G.; Kinasih, I.; Raffiudin, R.; Soesilohadi, R.C.H.; Purnobasuki, H. Pollination biology of yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) at typical Indonesian small-scale farming. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Long, X. Seed characteristics of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) rootstocks with different genotypes and responses of their seedlings to drought stress. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchia, M.; Haparipum, V.; Vanderplank, J. Passiflora Cultivars 2004–2010 (Registration Ref. #133): Cultivar Name P. ‘Soi Fah’. 2008. Available online: https://passiflorasociety.org/wp-content/uploads/R0133.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Passiflora Cultivars Registration Committee; Feuillet, C.; Frank, A.; Kugler, E.; Laurens, C.; MacDougal, J.; Skimina, T.; Vanderplank, J. Notes on the Passiflora Cultivars List. Passiflora 2000, 10, 21–39. Available online: https://www.passionflow.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/passiflora-hybrid-register-2000.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Chen, W.-C.; Chung, A.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Yang, S.-Z.; Chen, P.-H. Passiflora (Passifloraceae) in Taiwan. Phytotaxa 2022, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, I. La trionfante e gloriosa Croce, Trattato di Iacomo Bosio [The Triumphant and Glorious Cross, Treatise of Iacomo Bosio]; S.or Alfonso Ciacone: Chivasso, Italy, 1610; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).