Abstract

Edible flowers (EFs) form a special group of food plants that serve a pivotal role in local food systems, both in their utilitarian value and cultural significance. Dali, renowned for its rich biocultural diversity, is home to various ethnic groups with unique traditions regarding the consumption of EFs. However, systematic and comprehensive ethnobotanical studies of EFs are lacking, and their biocultural significance has not been discussed. Through ethnobotanical surveys conducted in 15 markets across Dali, 163 taxa of EFs were documented, encompassing 56 families and 108 genera. They were consumed in 16 ways and as 5 types of food. Quantitative evaluations using the Relative Occurrence Frequency (ROF) and Cultural Food Significance Index (CFSI) assessed the local importance of these flowers. Comparisons were made with another site regarding flower-eating species and methods, revealing biocultural differences. The study highlights how these flowers contribute to local dietary practices and cultural traditions. The role of EFs in sustainable food systems (SFS) is discussed, with emphasis on their economic, environmental, and social impacts. Protecting biocultural diversity means maintaining reciprocal relationships between people and edible species, which are crucial nodes in local SFS.

1. Introduction

The richness of dietary species reflects food biodiversity in diets, closely linked to the diet quality and human nutrition in a given area [1]. Of the nearly 400,000 species of vascular plants known to exist on Earth, only a few are widely cultivated and just three plants—rice, maize, and wheat—provide over 60% of the daily energy consumed by humans [2,3]. Dietary diversity remains limited, even in areas with high biodiversity [4]. The homogenization of global diets is becoming a threat to food security [5].

Edible plants are an integral part of human diets and traditional food systems [6]. The diversity of wild edible plants obtained on or near agricultural land, forests, and other natural landscapes, is a key source of resilience for food systems, especially in lean seasons and underdeveloped areas [7]. The traditional consumption of local edible plants is closely tied to the cultural interactions between plants and humans [8]. Related traditional knowledge is also crucial for food security, especially in the context of changing environmental conditions [9].

Flowers are precious resources not only for their ornamental qualities but also for their medicinal, food, and industrial uses [10]. Plants with edible flowers (EFs) are broadly defined as those in which entire flower organs or their components are considered edible [11]. As a healthy plant food, EFs are beneficial for both the human body and the environment [12]. Flower-eating is a common practice shared by people around the world, with 180 species consumed in all kinds of food and drinks [13]. However, the species, motivations, and methods of flower consumption vary across regional and cultural contexts [14]. Flower-eating plays an important role in different regional cultures and contributes significantly to local food systems, human diets, and physical health. In Mizoram, Northeast India, 59 EFs consumed by indigenous people diversify the food sources and stabilize local food security during challenging times [15]. In Mediterranean basin countries, 251 taxa of EFs are widely used for human nutrition and closely linked to both local floras and traditional knowledge [16]. For hundreds of years of tradition, Mexicans have regarded cooking and eating flowers and plants, alongside the consumption of other animals, as a sacred ritual, creating an inseparable bond between flowers and local cuisine [17].

Yunnan Province in southwest China is known for its rich biodiversity and cultural diversity. There are more than 300 EF species consumed by different linguistic groups according to a preliminary ethnobotanical survey [18]. An old saying, ‘flowers bloom in all seasons in Yunnan’, is widely known. Studies have shown that edible flowers are available throughout the year in Yunnan, with spring and summer offering the greatest abundance [19]. The traditional knowledge regarding EFs varies considerably across different linguistic groups. The methods of consuming EFs traditionally also differ across these groups [14]. The Bai people, residing in Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture in the central-western part of Yunnan, are one of the ethnic minorities in China with a long history and rich culture. Relying on abundant local plant resources, combined with their traditional dietary habits, the Bai people have, through long-term practice, identified and utilized numerous edible plants in all aspects of production, daily life, and diet. This has led to the development of a local food system and dietary culture that is distinctive among all of China’s ethnic groups [20].

Edible flowers are a special group of food plants that serve a pivotal role in local food systems, both for their utilitarian value and their cultural significance [11]. Previous studies on flower-eating in Dali Prefecture have documented some traditional knowledge of several species [21]. However, a detailed study on the diversity of EFs in Dali has not been conducted. The number of EF species traditionally consumed by the Dali people remains unclear. Flower-eating is a widespread and significant social phenomenon in Dali. The cultural significance of EFs and their role in the local food system merit further consideration. The main objectives of this study were to (1) document the diversity of EFs consumed in Dali, (2) reveal the flower-eating culture there, and (3) discuss its role in the local sustainable food system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sites

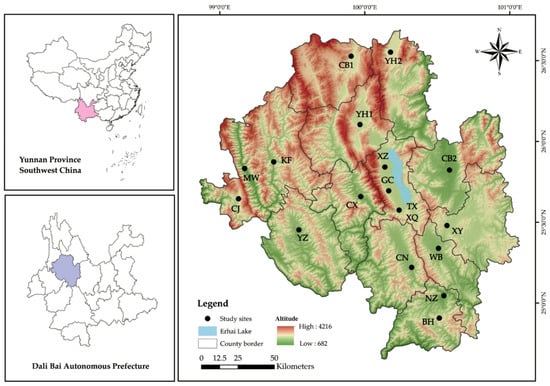

Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture is located in the central-western part of Yunnan Province, between 98°52′–101°03′ E and 24°41′–26°42′ N. It covers 29,459 square kilometers, with mountainous regions accounting for 93.4% of the area. Dali is situated on a low-latitude plateau with an annual average temperature ranging from 12 °C to 19 °C and an average annual precipitation of 836 mm. The region experiences minimal seasonal variation. The terrain is complex, with many lakes and basins. Elevation ranges from 730 m to 4295 m, resulting in significant vertical climatic differences. The area is rich in biodiversity and diverse vegetation types (www.dali.gov.cn, accessed on 17 August 2024).

Dali Prefecture is under the jurisdiction of one city, 11 counties, and 112 towns. Currently, it has a permanent population of approximately 3.34 million, comprising 13 ethnic groups: Han, Bai, Yi, Hui, Lisu, Miao, Naxi, Zhuang, Zang, Bulang, Lahu, Achang, and Dai. Historically, Dali has been well-known for its rich diversity of useful plants and cultural practices surrounding their use by these ethnic groups. For example, there has been a long tradition of the collection, cultivation, utilization, and trade of medicinal plants by the local villagers [22]. Dali Prefecture is both the origin and primary settlement of the Bai people with a population of 1.93 million. Approximately 80% of China’s Bai population resides here. Their adherence to animism and embrace of a sustainable approach to utilizing diverse plant species has fostered a distinctive biocultural heritage, including traditional practices such as meizi (plum) consumption and plant-dyeing techniques [23,24].

2.2. Ethnobotanical Survey

The field ethnobotanical surveys were conducted in Dali during six visits from April 2019 to March 2024. The local market served as the gateway to the local food system, housing the largest concentration of EFs and related traditional knowledge from both vendors and consumers [25,26]. Four periodic markets and 11 stable markets in Dali City and 11 other counties were covered in our study (Figure 1 and Table 1). Stable markets are typically located in easily accessible areas and offer the common vegetables and foods consumed by the locals, with regulated operations. Vendors are generally the same each day, and locals can visit at their convenience. Periodic markets are often held at regular intervals, such as every Monday or on dates containing “3”, in remote areas like the outskirts of towns or rural areas. With minimal regulation and open access for anyone to set up a stall, rare EFs, and uncommon species are more likely to be found in these markets.

Figure 1.

Study sites. Fifteen surveyed markets in Dali are marked with black dots. The names of the markets are abbreviated.

Table 1.

The location, linguistic groups, and number of informants in the markets were investigated.

The semi-structured interviews, key informant interviews, and participatory observation were conducted concerning the topics listed in Table 2. The number of informants was also recorded (Table 1). Some restaurants serving flower dishes in Dali were also investigated to add some information and provide additional insights. All interviews were made individually. Before the interviews, each informant was informed of the purpose of this study, and their consent was obtained.

Table 2.

Questions used for market interviews.

During the market surveys or en route to survey sites, voucher specimens of some EFs were collected and assigned numbers. The voucher numbers were included in the inventory of EFs in Dali. The nomenclature of all vascular plants follows iplant (http://www.iplant.cn/, accessed on 18–22 August 2024) and World Flora Online (http://www.worldfloraonline.org, accessed on 18–25 August 2024). Prof. Chunlin Long identified the plant species, and the voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium at Minzu University of China, Beijing.

2.3. Data Statistics and Quantitative Evaluation

2.3.1. Data Statistics

The information gathered from field surveys on Dali’s EFs and associated traditional knowledge was systematically reviewed, recorded, and organized, including species’ scientific names, vernacular names, growth types, edible parts of the floral organs, use types, pre-process and preparation methods, other parts when collecting or consuming flowers, medicinal value, and additional uses of the species. The edible parts of the floral organs were classified according to the Economic Botany Data Collection Standard [27]. The term “nectar” was added, as the nectar of some EFs can be consumed as a snack based on observations during the field survey in Dali. Since knowledge is usually lost when field material is converted into data matrices [28], we retained some detailed and non-standardized information in the columns “Edible parts of the floral organ”, “Methods of preparation for food” and “Additional use(s)” in the inventory. These data were manually categorized before being subjected to statistical analysis.

2.3.2. Quantitative Evaluation

ROF

The relative occurrence frequency index (ROF) in this study was used to evaluate the local importance of EFs in Dali.

ROF =OF/N

OF refers to the number of markets where the EF occurs while N is the number of markets surveyed. The index varies from 0 to 1. A higher ROF value means the EF is more widespread in local markets, reflecting greater importance in the local food system [29].

CFSI

The cultural food significance index (CFSI) was used to evaluate the cultural significance of EFs in Dali. Because the number of surveyed markets is counted and applied to the evaluation, the original index QI (frequency of quotation index) was replaced by OI (frequency of occurrence index) for a more accurate evaluation. The OI value is equal to the OF value. Edible flowers are a specific type of edible plant where the flower is the primary part used. There are many EFs whose other parts may also be consumed together with the flower. However, such uses do not enhance the cultural significance of the species as an EF [11]. Therefore, the PUI (parts used index) value is not calculated. The formula for calculating CFSI in this study is as follows:

CFSI = OI × AI × FUI × MFFI × TSAI × FMRI × 10−2

The CFSI includes the occurrence frequency (OI), the availability (AI, availability index), the frequency of use (FUI, frequency of utilization index), the type of food uses (MFFI, multifunctional food use index), taste appreciation (TSAI, taste score appreciation index) and the role as food medicine (FMRI, food-medicinal role index) [29,30,31]. AI correction index is also used to correct for the effects of ecological factors on the cultural significance of EFs [30]. The categories of each index are simplified (Table 3). The ROF and CFSI values for each EF are added to the database.

Table 3.

The categories of each index.

JI

The Jaccard index (JI) was used to evaluate similarities between the EFs of Dali with those of Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture. Xishuangbanna has been previously studied for the same purpose, using similar methods to examine the EFs of the region. Both Dali and Xishuangbanna are located in Yunnan Province and are known for their rich flora. However, their main ethnic groups are different, one is Dai and the other is Bai. In recent years, transportation conditions have significantly improved. Frequent trade and cultural exchanges occur between the two prefectures. Through evaluation and comparison, the prevalence and differences in flower-eating culture in Yunnan can be revealed. The reasons behind the formation of these unique flower-eating cultures can be speculated.

A is the recorded number of species of the current study area a, B is the documented number of species of another study area b, and C is the number of species common to both areas a and b [32].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Species Diversity of Edible Flowers

According to our field surveys, 163 taxa (including species and varieties) belong to 56 families, and 108 genera were documented as being used as EFs in Dali. Their scientific names, families, vernacular names, Chinese names, types, used parts, food categories, methods of preparation, additional uses, ROF values, CFSI values, and voucher numbers are listed in Table 4. It is important to note that the Bai language has been gradually influenced by Mandarin. As a result, in documenting species’ vernacular names, the versions in Yunnan dialects are largely equivalent to those in the Bai language.

Table 4.

The inventory of edible flowers consumed by people in Dali.

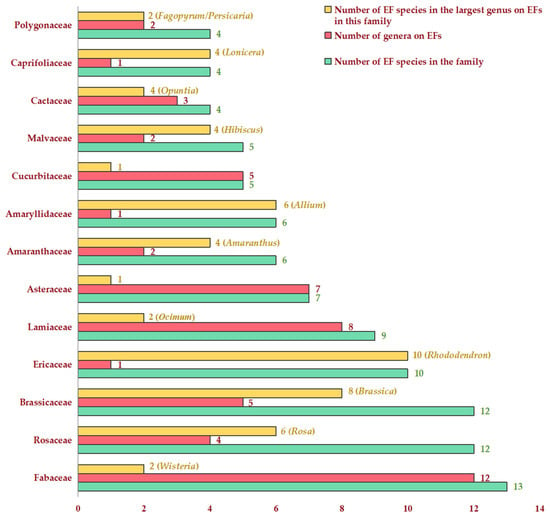

Among all the recorded EF species, Fabaceae was the largest family with 13 species (8.0%), followed by Rosaceae and Brassicaceae, each with 12 species (Figure 2, green bar). Rhododendron was the largest genus, with 10 taxa (Figure 2, yellow bar), and is the only genus in Ericaceae with EFs. Brassica also has many EFs, with 8 species, followed by Rosa and Allium. Families such as Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Asteraceae contain more genera with EFs, even though each genus has one or two EF species (Figure 2, red bar). There are 84 genera with only one species, showing the rich phylogenetic diversity.

Figure 2.

The diversity of families and genera.

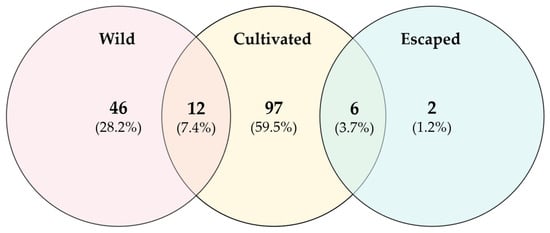

The growth types of EFs include cultivated (c), wild (w), and escaped (e). Of the 163 EFs in Dali, 115 (70.6%) EFs are cultivated or can be cultivated, including 7 imported species, which is more than the wild (58) and escaped (8) ones (Figure 3). Twelve species have both wild and cultivated types. Local communities in Yunnan are still in the process of recognizing and utilizing plants with edible floral organs. A significant number of EFs are repeatedly and sustainably utilized due to long-term cultivation, while many wild EFs could become key species for future development and utilization.

Figure 3.

The growth types of edible flowers.

Due to its unique topography, mild climate, and extremely high biodiversity, Dali has generated abundant edible plant resources. The large number of reported EFs serves as an important dietary buffer, providing nutrition and contributing to a unique culinary culture that attracts visitors to the region [33]. High dietary diversity refers to a greater number of food types or groups [7]. Although the high species diversity of EFs does not equate to high dietary diversity, it still broadens food choices for the local population, laying the foundation for high dietary diversity. The positive correlation between wild edible plants and dietary diversity was demonstrated [34]. A significant proportion of wild edible plants with nutritional advantages and endemicity, can provide a vital source of sustenance for local communities facing food insecurity or extreme famine [4].

3.2. Cultural Diversity of Edible Flowers

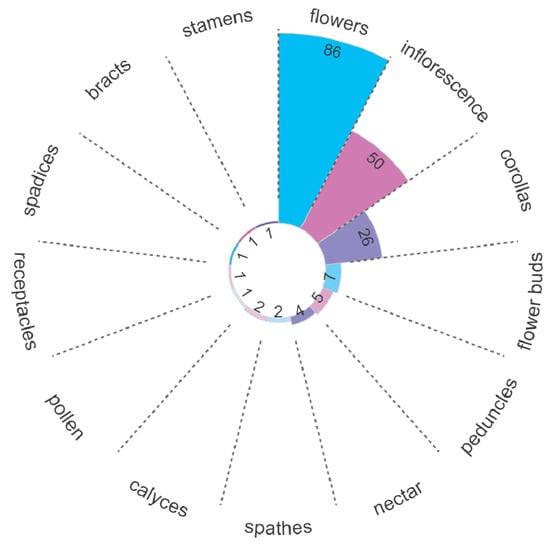

3.2.1. The Edible Parts of EFs

The edible parts of the floral organ are various, including inflorescence, spathes, spadices, flowers, flower buds, peduncles, receptacles, calyces, corollas, stamens, pollen and nectar (Figure 4). The most commonly consumed part is the flower as a whole (86 species, 52.8%), followed by inflorescence (50 species, 30.7%) and corollas (26 species, 16.0%). Most floral organs are collected or used alone (117 species, 71.8%). They are also used with other parts of the plant, being collected or consumed with leaves, stems, fruits, and shoots. Leaves are most often consumed with flowers (43 species), followed by stems (24 species). Three EFs are consumed with their young shoots and one with fruits. When locals collect or consume flowers, it is not always necessary to do so with other parts. The young and tender parts are often preferred when other parts are consumed together.

Figure 4.

The edible parts of the floral organ are used for food. The number of species consumed with this part of the floral organ is also shown.

3.2.2. The Consume Type and Methods

The EFs consumed by Dali people include vegetable(v), beverage(b), snack(sn), seasoning(se), and food dye(fd). Vegetables are the most common dietary type with 148 species (90.8%). Some EFs, such as Agastache rugosa, Basella alba, Brassica juncea, and Brassica rapa var. Glabra, are common vegetables in Yunnan (Figure 5A–D). Their flowers are so small that they are never consumed without stems and leaves. Compared to them, species such as Cucurbita moschata, Hemerocallis citrina, Rhododendron decorum, and Robinia pseudoacacia, whose inflorescences or flowers are consumed on their own, are true “flower vegetable” (Figure 5E–H).

Figure 5.

Some common EFs used as vegetables in Dali ((A). Agastache rugosa, (B). Basella alba, (C). Brassica juncea, (D). Brassica rapa var. glabra, (E). Cucurbita moschata, (F). Hemerocallis citrina, (G). Rhododendron decorum, (H). Robinia pseudoacacia).

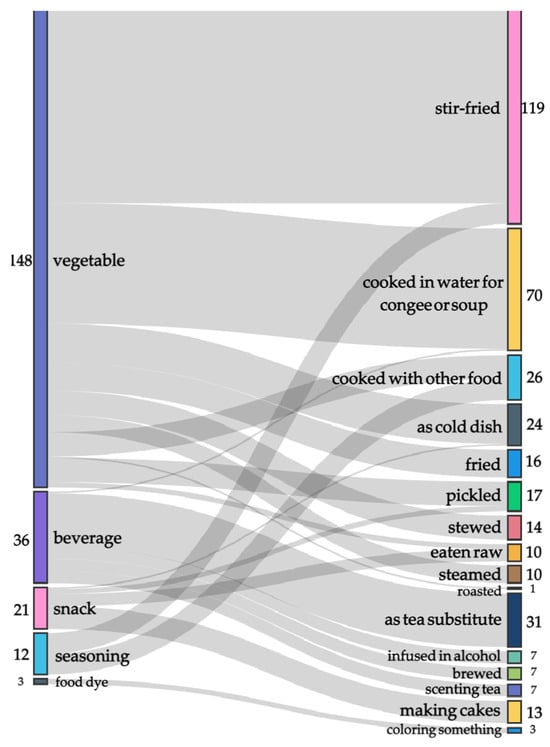

In addition to being used as vegetables, EFs in Dali are also used as beverages, snacks, seasonings, and food dyes. Forty-four EFs (27.0%) have more than one use type. Due to the diversity of species and dietary habits, EFs are prepared using a variety of methods (Figure 6). They can be stir-fried, cooked in water for congee or soup, steamed, stewed, pickled, fried, roasted, brewed, cooked with other food, eaten raw, infused in alcohol, used for coloring something, scenting tea, making cakes, or serve as cold dishes or tea substitutes (Figure 7). Being stir-fried (119, 73.0%) is the most common preparation method, followed by being cooked in water for congee or soup (70, 42.9%). They are all traditional Chinese cooking methods with the most commonly used.

Figure 6.

The diversity of use type of EFs and methods of food preparation.

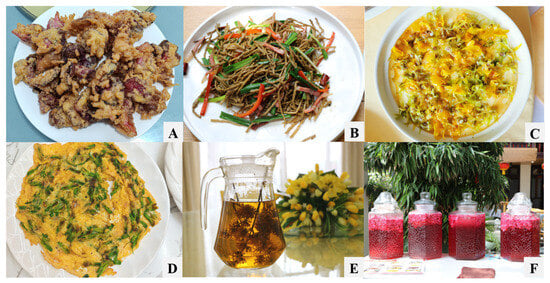

Figure 7.

EFs prepared using different methods. (A) Fried flowers of Camellia reticulata; (B) stir-fried male inflorescences of Juglans regia; (C) steamed flowers of Dendrobium officinale with eggs; (D) fried flowers of Caragana sinica with eggs; (E) steeped inflorescences of Buddleja officinalis as tea substitute; (F) infusing flowers of Rosa gallica ‘Dianhong’ into rice vinegar as a variety of local beverage called rose vinegar).

Among the 36 EFs used as beverages in Dali, 31 are used as tea substitutes, and 7 are used for scenting tea. Tea, a globally popular beverage, holds significant cultural and social importance in China. Yunnan is considered the botanical origin of tea (Camellia sinensis) in the world while Dali is one of the earliest areas in Yunnan to grow and consume tea [35,36]. Scenting tea refers to the mixture of flowers and tea to be consumed together, using the scent and color of the flowers to enhance the flavor. Tea substitutes are non-tea substances steeped in boiling water, serving as an alternative to real tea (the leaves of Camellia sinensis or C. taliensis). The practice of applying various flowers to tea is an extension of the rich tea culture. Similarly, a total of 13 EFs are brewed or infused in alcohol to make wine, which is part of Chinese drinking culture.

Snack is the third category of EFs consumed by local people in Dali, with a total of 21 species. Most of these are ingredients for making cakes, often as fillings. Ten EFs are consumed as a seasoning, a finding that is consistent with previous findings on the diversity of edible spice plants in Dali [20]. Being cooked with other food is the preparation method for all seasoning EFs, which is the fourth largest category of food preparation methods, with 26 EFs. In addition to the 12 EFs used as seasonings, 14 EFs are used as complementary ingredients in cooking, adding flavor and esthetic appeal to dishes. The floral organs of Buddleja officinalis, Hibiscus sabdariffa, and Rosa chinensis are used as food dyes to color rice or beverages.

Furthermore, 31 species of EFs (19.0%) require pre-processing, such as blanching in hot water, rinsing, soaking, or removing certain parts like stamens, spadices, receptacles, pistils, and peel of peduncles before cooking or consumption to eliminate bitterness or mild toxicity. Musa acuminata needs to be rubbed with salt. Almost all EFs from the genus Rhododendron are poisonous, requiring pre-processing before cooking. Specifically, removing the spadices of Colocasia esculenta is a traditional preparation method throughout Yunnan. In Dali, the spadices of C. esculenta can be deep-fried, then stewed or stir-fried with pork and chili peppers, and served either as a topping for noodles and rice noodles or as a side dish with alcohol.

3.2.3. The Additional Use(s)

There are multiple uses of flower-eating plants in Dali. In addition to their consumption as food, 125 EFs (76.7%) can be used for medicinal purposes, followed by 63 species for ornamental use and 26 for cultural practices. The floral organs of 66 EFs are used as medicine with clear specifications of the treated affections. The flowers of Dendrobium nobile, Houpoea officinalis, Lonicera japonica, Carthamus tinctorius, Crocus sativus, and others have long been recognized by traditional Chinese medicine. Though Carthamus tinctorius and Crocus sativus can be found in Dali markets, they are consumed for food purposes only infrequently. The culture surrounding local food plants is inextricably linked with traditional healing systems [37]. They hold the potential to provide valuable raw materials and relevant knowledge for the development of healthy food and drugs [38]. Our ethnobotanical study in Dali further emphasizes that flowers are a crucial plant part for medicinal use, which should not be ignored [11].

3.3. Biocultural Characteristics of EFs

3.3.1. The ROF and CFSI Value of EFs

The ROF and CFSI values for all recorded EFs were calculated and are shown in the inventory (Table 4). Detailed values for each factor of each EF are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). The ROF values range from 0.07 to 1.00. Eight EFs (Allium hookeri, Allium sativum, Brassica oleracea var. botrytis, Brassica oleracea var. italica, Brassica rapa var. chinensis, Brassica rapa var. glabra, Colocasia esculenta, Cucurbita moschata) were recorded in all 15 surveyed markets while 32 EFs only found in a single market. The CFSI values range from 0.03 to 864.00. These values are classified into six categories: very high (CFSI ≥ 300), high (CFSI= 100.00–299.99), medium (CFSI = 20.00–99.99), low (CFSI= 5.00–19.99), very low (CFSI= 1.00–4.99), and negligible (CFSI < 1.00) [30]. The majority of EFs (68.1%) fall into the ‘negligible’, ‘very low’, and ‘low’ groups. Twenty-two EFs have CFSI values exceeding 100, of which four exceed 300. Two flowers with the highest CFSI values, Rosa spp. (edible species, cultivars, or types) and Chrysanthemum morifolium, are worldwide EFs [13]. Following these, the flowers of Robinia pseudoacacia, Cucurbita moschata, and Allium tuberosum, also rank high in CFSI values and are more commonly consumed in southern China, though they can also be found in the north. Interestingly, some species with the highest ROF values do not exhibit similarly high CFSI values, such as those from the Brassica genus. They are commonly found in local markets and are important foods within local communities, but their cultural significance as true “edible flowers” is less pronounced. Conversely, some locally representative EFs, such as Ottelia acuminata and Rhododendron spp., have lower CFSI values, which could be influenced by factors such as the locals’ willingness to sell them, as well as the seasonal availability and the frequency of surveys.

3.3.2. Representative Edible Flowers

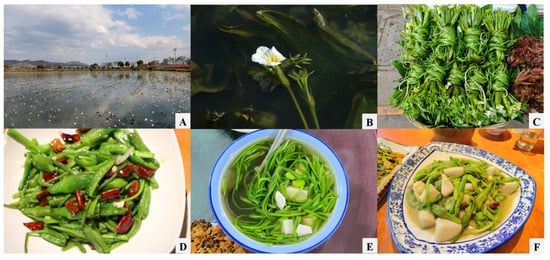

Ottelia acuminata

Ottelia acuminata is one of the most representative edible flower species in Dali (Figure 8). Commonly known as “Hai cai hua” in Chinese, the term “Hai” refers to the sea or huge water body. Because Yunnan is inland with numerous mountains, far from the actual sea, the locals use “Hai” to describe large lakes. For example, the Erhai watershed, a part of the Lancang River basin, is located in the center of Dali City. It is a famous lake with around 250 square kilometers. The term “Cai” means vegetable, while “Hua” means flower. Thus, in the view of the locals in Dali, O. acuminata is a species that grows in Erhai Lake and other wetlands with obvious flowers and is consumed as a vegetable.

Figure 8.

Ottelia acuminata and dishes (A). O. acuminata cultivation base in Eryuan County, Dali. (B) Flowers and peduncles. (C) O. acuminata sold in Dali’s market. (D) Stir-fried. (E) Soup made with O. acuminata and taros. (F) Stir-fried with taros.

O. acuminata belongs to the Hydrocharitaceae family. It is endemic to China with four known varieties distributed mainly in southwestern China, particularly in Yunnan Province. This aquatic plant thrives in lakes, ponds, ditches, and deep-water fields at altitudes below 2700 m. Apart from its floral organs, it is a perennial submerged plant that remains entirely underwater [39].

The Bai people of Dali have a long culinary tradition involving O. acuminata, with written records of its use dating back to the mid-19th century [40]. Locals typically consume the entire floral organ, with a particular preference for the slender flower stalk, sometimes along with a bit of stem and leaves. Traditional dishes include flower stalks cooked with tofu, or its stalks and stems cooked with taro. In Heqing County of Dali Prefecture, the Bai people also stir-fry the leaves and flower stalks with ham, and shredded pork, or pickle them for later consumption. Additionally, O. acuminata has a role in traditional Chinese medicine to treat various ailments, including urinary retention, constipation, heat-induced cough, hemoptysis, asthma, stranguria, and edema [39].

O. acuminata requires pristine water quality and can only thrive in clean, unpolluted waters. However, due to factors such as water pollution, changes in land use, the spread of invasive species, and the overstocking of grass carp (which feed on O. acuminata), its population in highland lakes has sharply declined [40,41]. As a result, O. acuminata has been classified as an endangered species and is listed as a national second-class protected plant in China.

In Yunnan, O. acuminata is highly regarded as a delicacy. As early as the 1980s, farmers in Eryuan County, Dali, began experimenting with the artificial transplantation of O. acuminata. Over time, they discovered that the O. acuminata thrives in nutrient-poor environments and is sensitive to pesticide pollution. Thus, they avoid using chemical fertilizers, manure, or pesticides during cultivation, ensuring the healthy growth of O. acuminata while preserving the cleanliness of the water it inhabits. With the support of government departments such as forestry, environmental protection, agriculture, and water resources in Yunnan Province, the area of O. acuminata cultivation has gradually expanded. The transplantation efforts by local farmers have proven effective as a form of ex situ conservation, protecting and managing the plant’s genetic resources and broadening its habitat. By 2023, the cultivation area of O. acuminata in Eryuan had reached 100 hectares, yielding 2700 tons and generating an economic output of 21.6 million yuan [42]. The plant can be harvested year-round, as its flower stalks continue to sprout, ensuring a consistent yield. This steady production has provided local villagers with a stable and sustainable source of income, contributing significantly to rural revitalization.

Rhododendron

In this study, we identified 10 species of EFs in the genus Rhododendron, making it the largest genus among all 108 genera documented. Yunnan Province is the origin and distribution center of Rhododendron species, offering a favorable climate, soil, and geographical advantages for their growth [43]. Dali is known as the “Kingdom of rhododendrons,” boasting abundant Rhododendron resources.

Plants in the genus Rhododendron are known for their toxicity. The local Bai people have long recognized this, referring to them as “poisonous flowers”. They believe that the deeper the flower color, the more toxic the plant is. Therefore, the local Rhododendron decorum, with its large, thick-petaled white flowers (Figure 9A), is the most popular edible rhododendron, holding the highest CFSI value among all Rhododendron EFs. R. pachypodum is another commonly consumed EF whose corolla has white petals with a faint red hue on the outer side [18]. Due to their pleasant taste and the long blooming period of one to two months, these species have become delicacies for the Bai people, often served at banquets, weddings, and funerals.

Figure 9.

Rhododendron decorum and dishes (A). R. decorum flowers. (B) Blanched and sold in markets. (C) Soup made with R. decorum and powder of beans. (D) Stir-fried with pork.

The locals in Dali have developed specific methods for harvesting and processing rhododendrons. Since the pollen contains mild toxins, people with weaker health are advised to avoid gathering them, as it may cause dizziness, palpitations, or even vomiting. Only individuals in good health can go up the mountain to collect flowers, with an average daily harvest of about 50 kg. The harvested flowers are typically not stored overnight to avoid spoilage. The edible parts, primarily the corollas, are carefully separated from the toxic stamens and boiled for a few minutes before being soaked in cold water. The flowers are then rinsed for 3 to 5 days, with the water changed daily to remove bitterness and toxins. In the market, it is common to find rhododendrons that have already been blanched (Figure 9B). These flowers are often cooked or stir-fried with broad beans, pork, or ham (Figure 9C,D), and can also be pickled for long-term preservation and consumption. The boiling and rinsing times are carefully controlled, as excessive time is believed to diminish the medicinal benefits of the flowers.

Every May to June, locals in Dali consume various native rhododendrons. Consuming rhododendrons during this season is believed to help the body acclimate to changes in the environment and promote health. However, different ethnic groups hold varying beliefs regarding its benefits. The Bai people believe that consuming rhododendrons aids digestion and helps reduce fat storage in the body, while the Naxi people regard the white flowers of rhododendrons as nourishing for both humans and animals. For the Lahu people, rhododendrons are considered medicinal flowers that promote digestion, and they often serve rhododendron-based dishes to guests [44]. Nutritional studies on Rhododendron decorum have found that its flowers are rich in vitamin B6, minerals, and amino acids [45].

People in Dali consciously protect R. decorum and its habitats during harvesting and other activities for the importance of the species for local consumption. Research on the genetic diversity of R. decorum indicates that its utilization by local people has not led to a decline in genetic diversity [46]. However, due to the climatic and land use changes expected over the next 50 years, many Rhododendron species are expected to be negatively affected. All wide-ranging species, including R. decorum the local community most consumed, will likely decrease [47]. Therefore, it is important to manage the Rhododendron resources in Dali rationally and make them sustainable by maximizing their positive impact on the local food system.

Edible roses

Rose is a worldwide edible flower. Consuming roses is common in China, such as eating rose flower cakes produced from Yunnan, as well as drinking ‘rose tea’ which is made by steeping rose petals or buds in boiling water as a tea substitute. ‘Rose tea’ is particularly favored by young people as an alternative to traditional tea. In Yunnan Province, the consumption of roses is particularly prevalent. Several varieties of edible roses commonly used as food in Dali Prefecture are mainly Rosa gallica ‘Dianhong’ (Dian Hong in the local language), Rosa chinensis ‘Crimson Glory’ (Mo Hong), Rosa centifolia (Qianye Meigui), and Rosa damascena (Damashige Meigui) [48]. There has been the tradition of consuming roses for more than one hundred years in a variety of ways, such as soaking the flowers in cool water, removing the petals, and scrambling them with eggs—a traditional rose delicacy commonly prepared in households.

The utilization of roses in Dali extends beyond local markets and household kitchens. Rose products, particularly rose flower cakes, have become emblematic of Yunnan’s edible flower industry. With over a century of consumption history, rose flower cakes have developed into a well-established industry, with refined processes for cultivation, harvesting, storage, processing, and production. In addition to rose tea and cakes, a wide range of rose-based products is available, including rose vinegar, rose jam, rose cheese, and rose brown sugar. These products are popular among locals and tourists and are sold across China (Figure 10) [49].

Figure 10.

Rosa chinensis ‘Crimson Glory’ and diversity of rose products.

In particular, people in Dali enjoy making rose flowers into rose jam, which is primarily used to sweeten various rice and flour-based foods. There is a famous local saying: “Rose jam paired with Xizhou baba and roasted milk fan is a perfect match. Eating Xizhou baba and roasted milk fan without rose jam is like eating without a soul” [20]. Both Xizhou baba and roasted milk fan are famous traditional local snacks made from wheat flour and milk, respectively.

Integrating EFs with local specialties not only enhances the appearances and flavors of local products, thereby increasing their market appeal but also promotes the development of edible flower cultivation and related industries. Roses, in particular, play a significant role in this trend. Beyond their culinary use, roses are harvested for essential oil extraction, which is widely applied in cosmetics, chemicals, and other industries. The edible rose industry in Yunnan has scaled up significantly, developing a complete industrial chain and accumulating advanced knowledge and technology in cultivation and processing. As a result, Yunnan has become a leading region for the industrial production of edible flowers [50].

3.4. Comparison with EFs in Xishuangbanna

Xishuangbanna is an autonomous prefecture in South Yunnan. Because of the geographical environment and rainforest climate, it is one of the areas with the richest biodiversity in China [51]. The ethnobotanical study conducted in Xishuangbanna shows 212 taxa EFs there with diverse delicacy culture [11]. The number of EFs in Dali is less than that in Xishuangbanna, supporting the trend of decreasing EF diversity from south to north in Yunnan [19]. The JI value of 31.12, with 89 EFs shared between the two regions, indicates a relatively high similarity in their EFs.

Dali is situated in the northwestern part of Yunnan with a low-latitude plateau monsoon climate, while Xishuangbanna has a tropical monsoon climate. Dali’s average elevation is about 1 km higher than that of Xishuangbanna, and the ethnic compositions of the two regions are also quite different. Both regions possess a large variety of distinct EFs. However, there are exceptions. Binchuan, a county in the eastern part of Dali Prefecture, is located along the southern bank of the Jinsha River’s hot and dry valley. Its annual average temperature is about 3 °C higher than that of Dali Prefecture, enabling the growth of some tropical EFs such as Bombax ceiba, Melastoma malabathricum, Ocimum basilicum, and Tamarindus indica.

In recent years, the rapid economic growth driven by tourism and urban development has contributed to enhanced transportation networks, facilitating the exchange of species, biocultural knowledge, and ethnic cultures. This has led to the presence of shared EFs between the two regions. For example, tropical species like Musa acuminata flowers, native to humid, warm climates, have begun to appear in Dali’s markets. The common EF Rhododendron decorum of Dali can also be found in Xishuangbanna. These overlapping EFs, mostly widely cultivated species, suggest that flower-eating practices are widespread across Yunnan.

In Xishuangbanna, where the dominant linguistic groups are Dai, Hani, and Yao, people favor consuming the inflorescences or floral parts of Musa acuminata, Bauhinia variegata var. candida, Mayodendron igneum, and Gmelina arborea, etc. These species thrive only in the specific environment and climatic conditions of Xishuangbanna [11]. In contrast, in Dali with cooler climates, species like Ottelia acuminata or Rhododendron spp. are more prevalent. In addition to species, traditional knowledge such as cooking methods also differ. Although Buddleja officinalis is found in both prefectures, the Bai people, who are the primary linguistic group in Dali, rarely use it to dye rice, while the yellow rice dyed with it is an essential food for the Dai people in Xishuangbanna for their New Year celebrations. People in Dali favor making dairy-based snacks paired with rose jam, a practice unique to Dali. People in Xishuangbanna are skilled in using large leaves of Musa spp. in their daily lives. A distinctive traditional cooking method in Xishuangbanna is called “bao shao”, where food is wrapped in big leaves of Musa spp. or Phrynium rheedei and then roasted directly over charcoal. This practice is absent in Dali, except in Dai restaurants run by people from Xishuangbanna or other southern Yunnan regions.

Despite these differences in the edible species and methods, both two prefectures share certain commonalities in the flower-eating culture. In Dali, consuming white Rhododendron flowers is a sign of the beginning of spring. This tradition is similar to that in Xishuangbanna, where people enjoy the white flowers of Bauhinia variegata var. candida as a reminder to start spring plowing. Both flowers have large groups of people who consume them, making the consumption of these white flowers a significant tradition and custom in their areas. These practices have become significant cultural traditions and have extended to surrounding prefectures, symbolizing the rich culinary heritage of Yunnan’s flower-eating culture.

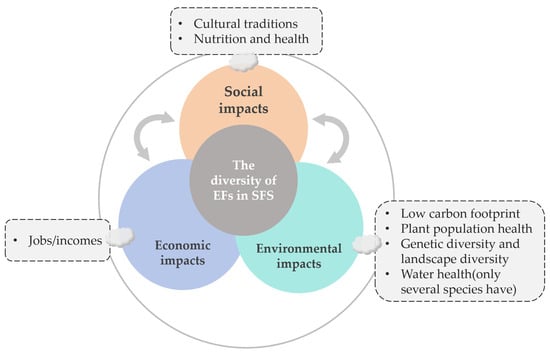

3.5. Contribution to the Sustainable Food System

Food biodiversity, which refers to the diversity of organisms used for food, is essential for sustainable food systems (SFS) [1]. According to FAO, an SFS not only provides food security and nutrition for all but also ensures the economic, social, and environmental foundations to sustain food security and nutrition for future generations are not compromised [52]. Edible flowers in Dali, as a traditional type of local food, offer nutritional and health benefits to the community. They also hold unique cultural significance and contribute to environmental and economic sustainability, playing a key role in the region’s local SFS (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The impacts of three aspects of the diversity of edible flowers in SFS.

3.5.1. Economic Impacts

The rich diversity of EFs supports the local subsistence and translates into economic benefits for the community [33]. All EFs surveyed from the Dali markets contribute to vendor’s incomes. Although most EFs were not sold as frequently as common vegetables, some representative species, such as Ottelia acuminata, Rhododendron decorum, R. pachypodum, Cucurbita moschata, Caragana sinica, and Colocasia esculenta, are commonly found in many stalls and local restaurants. The collection and marketing of Rhododendrons involve multiple value chains [26]. Various rose products are sold all over China, bringing long-term profits to vendors and self-employed individuals. Villagers engaged in large-scale cultivation of Ottelia acuminata or edible roses rely on these flowers for their livelihood. Therefore, the economic impacts of these EFs are integral to the local SFS.

3.5.2. Environmental Impacts

Locally sourced food with minimal transportation helps reduce food-miles emissions [53]. As a low-carbon diet, plant-based foods can significantly reduce costs on production-related health burdens and ecological degradation while curbing carbon emissions, delivering socio-economic benefits while mitigating climate change [54]. Most of the EFs in Dali are locally sourced, being a local food supply with a low carbon footprint. The consumption of exotic foods and processed products may be offset to some extent by the consumption of local EF. Meanwhile, the locality of the food supply can leverage regional biodiversity and ecological interactions to reduce reliance on external inputs and face multiple external shocks better, since the global food system relying on international cooperation deeply is often affected by political barriers and economic constraints [55,56]. A constant and stable supply of food is vital for creating an SFS [9].

Furthermore, the flower is a sustainable organ compared with the root and stem which are the functional but unsustainable organs of medicinal plants [29]. Collecting and consuming inflorescences and flowers have a lesser negative impact on plant populations compared to other plant parts. The rich genetic resources of EFs have been preserved through long-term cultivation, management, and utilization by local communities. For collection and consumption, some EFs are cultivated on a large scale. The hills adorned with white blossoms of Rhododendron spp. and the ponds dotted with the pure white Ottelia acuminata create beautiful landscapes. Additionally, some EFs are beneficial to their habitat. For example, O. acuminata helps purify water bodies by absorbing nitrogen and phosphorus in the water, improving water quality and offering ecological benefits [41].

3.5.3. Social Impacts

Humans have long relied on edible plants for sustenance. In many isolated and impoverished areas, edible plants provide essential nutrients, supporting the lives of the local people [29,31]. Studies show that many EFs are rich in protein, vitamins, minerals, fiber, and carbohydrates. A total of 302 bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, alkaloids and organic acids, with 22 biological activities have been identified in various EFs [10,57].

Beyond their nutritional and health benefits, edible plants also serve as important social and cultural carriers, facilitating communication and promoting social cohesion within communities [58]. Flower-eating is a prevalent practice in Yunnan, not only because of the abundance of plant resources but also because it is deeply rooted in local tradition and dietary habits, rather than being simply a personal preference [14]. The associated traditional knowledge and practices have been accumulated, preserved, and transmitted over an extended period of time, forming rich biocultural diversity. In Dali, for example, different flower parts can be prepared in 16 distinct methods, yielding 5 distinct types of food. The local community possesses a clear understanding of which EFs necessitate specific processing prior to cooking to eliminate any potential toxicity or bitterness, as well as which can be harmoniously cooked with other plant parts such as stems and leaves.

The biocultural diversity of EFs is a key component of the SFS, driving the consumption of EFs and their economic value. Continuing the tradition of flower-eating is profitable for some locals, and thus the practice can be preserved and even expanded. For large-scale cultivated species such as Ottelia acuminata and roses, their habitats must be protected to ensure successful harvests. For instance, the water bodies where Ottelia acuminata grows need to remain clean, and transplantation and cultivation practices should be diversified to preserve and enhance genetic resources. All in all, biocultural diversity fosters a virtuous cycle within local food systems by positively mobilizing communities. Protecting biocultural diversity means maintaining the reciprocal relationships between people and edible species, which are crucial nodes in the local SFS.

4. Conclusions

Through ethnobotanical surveys conducted across 15 markets in Dali, 163 taxa of EFs from 56 families and 108 genera were documented. The people in Dali possess abundant traditional knowledge of EF species, preparation methods, and their cultural identities. Some edible plants, whose flower is one of the edible parts, exhibited high ROF values but low CFSI, reflecting minimal cultural significance. Ottelia acuminata, Rhododendron, and Rosa are representative EFs in Dali, with a long history of consumption and unique cultural connotations. The flower-eating species and culture in Dali are different from that in Xishuangbanna, highlighting the shared yet diverse practices of EFs in Yunnan. The diversity of EFs plays an important role in sustaining local food systems for its economic, environmental, and social impacts, of which the biocultural aspect is a crucial node.

However, it is important to note that this study only documented EFs found in markets. Although some restaurants were also surveyed to add additional information, it is possible that some EFs are only utilized in households or in some villages that were not included in the study. The CFSI results indicate that most EFs have minimal cultural significance and occupy a marginal position within the local food system. Those that are frequently utilized and valuable are undoubtedly placed on the market and traded. Consequently, our study encompasses the representative EFs in Dali, which can reflect the real situation of EFs there.

Cultural and traditions greatly influence local diets [26]. Diets that align with local culture are essential for the adoption of healthy and sustainable diet policies, thereby benefiting local communities, as well as the environment and the economy [59]. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the diversity and significance of EFs in Dali’s food system, offering guidance for promoting healthier diets and supporting sustainable development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17010070/s1. Table S1: CFSI data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and C.L.; methodology, Q.Z.; field survey and data collection, Q.Z. and J.Z.; plant species identification, C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; review, C.X. and C.L.; data analysis, Q.Z.; funding acquisition, X.W. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Yunnan Provincial Sci and Tech Talent and Platform Program (202305AF150121), the Mekong-Lancang Cooperation Program (HX2023052) under the project ‘Sustainable conservation and value adding locally edible floral species in the Mekong regions’, and by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370407, 31761143001 and 31870316).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study was included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shengji Pei from the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for his encouragement and helpful suggestions. We are very grateful to the local people in Dali, Yunnan Province, who provided valuable information about edible flowers and hospitality. Members of the Ethnobotanical Laboratory at Minzu University of China were appreciated. In the section of the article dedicated to quantitative methods, Shuwang Hou provided much enlightening advice, for which the authors are grateful.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lachat, C.; Raneri, J.E.; Smith, K.W.; Kolsteren, P.; Van Damme, P.; Verzelen, K.; Penafiel, D.; Vanhove, W.; Kennedy, G.; Hunter, D.; et al. Dietary Species Richness as a Measure of Food Biodiversity and Nutritional Quality of Diets. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pironon, S.; Soto Gomez, M. Plant Agrodiversity to the Rescue. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, L.; Randrianarivony, T.; Randrianasolo, A.; Rakotoarivony, F.; Andriamihajarivo, T.; LaBrier, M.; Gyimah, E.; Vie, S.; Nunez-Garcia, A.; Hart, R. Wild Foods Are Positively Associated with Diet Diversity and Child Growth in a Protected Forest Area of Madagascar. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2024, 8, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Bjorkman, A.D.; Dempewolf, H.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Guarino, L.; Jarvis, A.; Rieseberg, L.H.; Struik, P.C. Increasing Homogeneity in Global Food Supplies and the Implications for Food Security. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4001–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R. Wild Edible Plants: A Challenge for Future Diet and Health. Plants 2022, 11, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.; Thilsted, S.H.; Ickowitz, A.; Termote, C.; Sunderland, T.; Herforth, A. Improving Diets with Wild and Cultivated Biodiversity from across the Landscape. Food Sec. 2015, 7, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.J.; Migliorini, P.; Pieroni, A.; Dreon, A.L.; Sacchetti, L.E.; Paoletti, M.G. Edible and Tended Wild Plants, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Agroecology. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 198–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture; FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments; FAO Commission: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Cui, L.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, L.; Chen, S.; Xi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W. Flowers: Precious Food and Medicine Resources. Food Sci. Hum. Well 2023, 12, 1020–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Sommano, S.; Wu, X.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical Study on Edible Flowers in Xishuangbanna, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Shen, J.; Xuan, J.; Zhu, A.; Ji, J.S.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Zong, G.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns in Relation to Mortality among Older Adults in China. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Li, M.; Yin, R. Phytochemical Content, Health Benefits, and Toxicology of Common Edible Flowers: A Review (2000–2015). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, S130–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Long, C. Cultural Dimension in Edible Flowers among Ethnic Groups in Yunnan. Nat. J. 2001, 23, 292–297+246–310. [Google Scholar]

- Khomdram, S.; Fanai, L.; Yumkham, S. Local Knowledge of Edible Flowers Used in Mizoram. Indian. J. Tradit. Know 2019, 18, 714–723. [Google Scholar]

- Motti, R.; Paura, B.; Cozzolino, A.; Falco, B. de Edible Flowers Used in Some Countries of the Mediterranean Basin: An Ethnobotanical Overview. Plants 2022, 11, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulík, S.; Ozuna, C. Mexican Edible Flowers: Cultural Background, Traditional Culinary Uses, and Potential Health Benefits. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Long, C. Studies on Edible Flowers Consumed by Ethnic Groups in Yunnan. Acta Bot. Yunnan 2001, 23, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, W.; Li, W.; Sun, Y.; Xu, M. Investigation on Vegetable-Edible Flower Plant Resources and Anthophagy Culture in Yunnan Province. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2017, 18, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, C. Resources Diversity of Edible Spice Plant of Dali Bai Nationality. Chin. Wild Pl. Resour. 2023, 42, 103–106, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, M. The Yunnan Bai People’s Flower Eating Customs. Yunnan. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Mater. Med. 2016, 37, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, Y.; Gou, Y.; Pei, S.; Wang, Y. Plants for Health: An Ethnobotanical 25-Year Repeat Survey of Traditional Medicine Sold in a Major Marketplace in North-West Yunnan, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, A.; Hamilton, A.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L. Indigenous Knowledge of Dye-Yielding Plants among Bai Communities in Dali, Northwest Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Li, B.; Lu, X.; He, L.; Jiang, X.; Tan, Q.; Long, C. Meizi-Consuming Culture That Fostered the Sustainable Use of Plum Resources in Dali of China: An Ethnobotanical Study. Biology 2022, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zocchi, D.M.; Mattalia, G.; Aziz, M.A.; Kalle, R.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. Searching for Germane Questions in the Ethnobiology of Food Scouting. J. Ethnobiol. 2023, 43, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, X. Poisonous Delicacy: Market-Oriented Surveys of the Consumption of Rhododendron Flowers in Yunnan, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, F. International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Science. In Economic Botany Data Collection Standard; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: London, UK, 1995; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł. Descriptive Ethnobotanical Studies Are Needed for the Rescue Operation of Documenting Traditional Knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Lin, S.; Wu, Z.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, C.; Li, J.; Long, C. Study on Medicinal Food Plants in the Gaoligongshan Biosphere Reserve, the Richest Biocultural Diversity Center in China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Evaluation of the Cultural Significance of Wild Food Botanicals Traditionally Consumed in Northwestern Tuscany, Italy. J. Ethnobiol. 2001, 21, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Lu, X.; Lin, F.; Naeem, A.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical Study on Wild Edible Plants Used by Dulong People in Northwestern Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, M.O.; Feng, G.; Khan, M.N.A.; Barlow, J.W.; Ankhi, U.R.; Hu, S.; Kamaruzzaman, M.; Uddin, S.B.; Hu, X. Qualitative and Quantitative Ethnobotanical Study of the Pangkhua Community in Bilaichari Upazilla, Rangamati District, Bangladesh. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, P. Ethnobotanical Knowledge against the Combined Biodiversity, Poverty and Climate Crisis: A Case Study from a Karen Community in Northern Thailand. Plants People Planet 2022, 4, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broegaard, R.B.; Rasmussen, L.V.; Dawson, N.; Mertz, O.; Vongvisouk, T.; Grogan, K. Wild Food Collection and Nutrition under Commercial Agriculture Expansion in Agriculture-Forest Landscapes. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 84, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, X.; Luo, B.; Long, C. Traditional Management of Ancient Pu’er Teagardens in Jingmai Mountains in Yunnan of China, a Designated Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems Site. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, G.; Chen, L.; Kang, G.; Hei, L.; Liu, B.; Rao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M. Research on Countermeasures of High-Quality Development of Tea Industry in Dali prefecture of Yunnan Province under the Background of Rural Revitalization. J. Tea Commun. 2024, 03, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, S.; Geng, Y.; Wang, C.; Yuhua, W. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Dietary Plants Used by the Naxi People in Lijiang Area, Northwest Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Zou, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, X. The Effects and Underlying Mechanisms of Medicine and Food Homologous Flowers on the Prevention and Treatment of Related Diseases. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, H.; Dao, Z.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical Study on Ottelia acuminata, an Aquatic Edible Plant Occurring in Yunnan. J. Inn. Mong. Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed) 2010, 39, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. The Flourishing and Declining of Ottelia acuminata in the Lake Dianchi. J. Yunnan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1985, 7, 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, N. Study on the Response Mechanism of Ottelia acuminata to Different Level of Nutrition and Heavy Metal Stress. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan University, Yunnan, China, 2022; 9p. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Jin, Z.; Lu, N. Ottelia acuminata at the Source of Erhai Lake. J. Changjiang Veg. 2024, 12, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Wang, Q. Study on the Distribution about Rhododendron Landscape Resources in Yunnan. J. Southwest For. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 44, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical Studies on the Edible Flowers in Lahu Societies. Guihaia 2007, 27, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, S. Traditional Culture of Flower Eating on Rhododendrom and Bauhinia in Yunnan, China. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Flower-Eating Culture in Asia; Seibundo Shinkosha Publishing Co., Ltd: Tokyo, Japan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Long, C. Assessing the Genetic Consequences of Flower-Harvesting in Rhododendron decorum Franchet (Ericaceae) Using Microsatellite Markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013, 50, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wang, T.; Groen, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Yang, X.; Ma, K.; Wu, Z. Climate and Land Use Changes Will Degrade the Distribution of Rhododendrons in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Yan, H.; Tang, K.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, X.; Jian, H.; Li, S.; Wang, Q. Evaluation of Yield and Analysis on Nutrient Compositions of Four Edible Rose Varieties in Yunnan Province. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 35, 2627–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yuan, Y. Food Tension-History and Modernity of Folk, Regional Market, Country and Flower Cakes. J. Chuxiong Norm. Univ. 2019, 34, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Yang, M.; Tian, Y.; Lin, Q. Overview of Edible Flowers in Yunnan. Food Ferment. Sci. Tech. 2017, 53, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.; Yu, J.; Tang, D.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Mou, Y. Investigation on the Medicinal and Edible Plant Resources of Dai Nationality in Xishuangbanna. Biot. Resour. 2021, 43, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. Sustainable Food Systems: Concept and Framework; Introduction to Sustainable Food Systems and Value Chains; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Jia, N.; Lenzen, M.; Malik, A.; Wei, L.; Jin, Y.; Raubenheimer, D. Global Food-Miles Account for Nearly 20% of Total Food-Systems Emissions. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.; Guo, M.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Low-Carbon Diets Can Reduce Global Ecological and Health Costs. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, P.; Benton, T.G.; Beddington, J.; Flynn, D.; Kelly, N.M.; Thomas, S.M. The Urgency of Food System Transformation Is Now Irrefutable. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 584–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, J.; Mole, F.; Johnston, H.; McCray, S. Quantifying the Locality of the Food Supply in a Large Healthcare Organization. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Ujala; Bhargava, B. Phytochemicals from Edible Flowers: Opening a New Arena for Healthy Lifestyle. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 78, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Peng, L.; Li, W.; Luo, J.; Li, Q.; Zeng, H.; Ali, M.; Long, C. Traditional Knowledge of Edible Plants Used as Flavoring for Fish-Grilling in Southeast Guizhou, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, J.; Huang, Z.; Huang, J.; He, J.; Liu, L.; Xia, M.; Liu, Y. Adoption of Region-Specific Diets in China Can Help Achieve Gains in Health and Environmental Sustainability. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).