Abstract

The fungarium was collected by Jerzy Wojciech Szulczewski in the Wielkopolska region in Western Poland in 1909–1911, 1928, and 1960–1966 (nine volumes). It includes dried plant specimens with disease symptoms of fungal origin and is currently located in the POZ Herbarium (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland). It is one of the oldest and richest Polish collections of this category although some parts were destroyed or lost after the Second World War. Many of the sheets have original annotations by the author and hand-written labels with both plant and fungus names. A checklist of all species is presented in the appendix. The whole collection was digitized in 2023 and is available on the website of the AMUNATCOLL project.

1. Introduction

The most widely recognized research activity undertaken in herbaria is plant identification. Many of them provide dry specimens, e.g., for comparative morphological analysis, assessment of species richness, and biodiversity monitoring [1]. Their important role has been to recognize not only the species that are ambiguous or difficult to interpret but even common ones. The use of herbaria in relation to the description of new species, and the necessity to refer to the type specimens from collections, reflect the increasing interest in herbaria as a source of genomic data [2]. Although plant conservation causes the degradation of genetic material in dry specimens (DNA chain shortening), the improvement of analytical methods (e.g., DNA sequencing) makes it possible to include herbarium specimens in phylogenetic studies as well [3,4]. Categorization of the various uses of herbaria in ecology has emphasized the importance of understanding the relations between plant samples and their associated micro- and macro-organisms [2]. The presence of a fungal fruiting body in contaminated plant material (fungal DNA is better preserved over time than plant DNA) multiplies the value of such material for further research [5]. This underlines the increasing utility of this kind of fungarium as a source of genomic fungal and plant data. This field of research is continuing to grow [2].

The large fungarium assembled by Jerzy Wojciech Szulczewski includes desiccated plant specimens with disease symptoms of fungal origin, collected in the Wielkopolska region for over 50 years, now housed in the Herbarium of the Department of Systematic and Environmental Botany (formerly Department of Plant Taxonomy), Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań (POZ). It is one of the oldest and richest Polish collections of this kind. The whole set safely survived the Second World War and endured two departmental moves. Since samples of plant pathogenic fungi are subject to degradation over time or could be lost, they were digitized to prolong their usefulness. The digitization initiative in 2023 at the AMUNATCOLL project made the collection more widely available [6,7,8,9,10].

2. About the Collector

Jerzy Wojciech Szulczewski (1879–1969), the collector of fungarium (Figure 1), was a man of three great talents: an educator, a researcher–scientist, and a social counselor. In each of these fields, and at every stage of his busy life, he demonstrated excellence.

Figure 1.

A portrait of Jerzy Wojciech Szulczewski, a man from the boundary of epochs, nations, and cultures. Drawn by Stanisław Mrowiński, changed.

Half of Szulczewski’s life (childhood and youth) passed under Prussian rule. Even his Christian name was Germanised: officially he ceased to be Wojciech and became Adalbert. Wielkopolska (Greater Poland) was then part of Prussia, and German was the official and scientific language. However, his upbringing in a patriotic Polish family and the influence of his mother, who nurtured folk traditions, songs, and legends, had a long-lasting impact on his attitude and beliefs [11]. After graduating from the teachers’ college of his dreams, he was a teacher and later headmaster of a school in Brudzyń near Żnin from 1899 to 1919. As a passionate naturalist, he regularly organized excursions and collected natural history specimens. An important part of his passion for folklore was collecting the texts of songs, legends, and fairy tales from the Kuyavia and Wielkopolska regions. He befriended Otto Knoop, a professor at the grammar school in Rogoźno, and thanks to him gained the opportunity to publish the texts in the Rogasener Familienblatt from 1901. In 1906—at the time of increased Germanization of the Polish nation—he published a collection of 50 Kuyavian tales in a book About any people wandering in Kuyavia [Allerhand fahrendes Volk in Kujawien].

His early output also includes the popularization of knowledge about all manifestations of plant life. As a biology teacher with an amateur passion for fungi, he collected many live specimens of Basidiomycetes during school trips in the local forests and displayed them for didactic purposes at numerous exhibitions. As a passionate naturalist, he regularly organized nature walks and collected natural history specimens to show them to children and adults. In his Beitrag zur Pilzflora von Brudzin im Kreise Znin [12] he characterized 162 species of fungi, on the basis of the classification of genera and species in Die Pilze by Otto Wünsche (available after translation into French in 1883 as Flore generale des champignons by J.-L. de Lanesson). Szulczewski was amazed that people do not notice the richness of fungal species at all, seeing only edible mushrooms, which were harvested for drying, preserving, or direct consumption. He stated that few mushrooms are familiar to the pickers (under folk names), including about 6–7 species of the genus Boletus (cep, porcini, penny bun, boletes) and single species from the genera Psalliota (syn. Agaricus; horse mushroom), Lepiota (parasol mushroom); and Cantharellus (chanterelle). Fortunately, local pickers distinguished also poisonous mushrooms (e.g., species of the genus Amanita—toadstools) and were aware of their dangerous toxins [12].

During the same period, another important work was already being realized by Szulczewski and published as Verzeichnis zum Herbar Posener Pilze in 1910 [13]. He based the taxonomy of his work on Systema Mycologicum [14] and identified fungal species on the basis of the morphology of their fruiting bodies with a light microscope only. Plant pathogenic fungi, included over 100 specimens of host plants infected by 32 specimens of pathogens from the classes Oomycetes and Ascomycetes, with only 3 species of Ustilaginales and 22 species of Uredinales, forming aecidia and teleutospores [13]. That article foreshadowed the future huge collection of the fungarium, which was continued uninterruptedly from 1909 to 1960.

He began his mycological work thanks to cooperation with Dr Franciszek Chłapowski—the head of two departments of the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning and custodian of its natural history collections. Thanks to this association, Szulczewski found a safe place for his specimens.

Szulczewski developed social activities as a counselor of the poor, and later as Chairman of the Peasant Council in Brudzyń near Żnin. For Szulczewski it was a quiet time in the Wielkopolska region, when he could devote himself to his work. It was then that the richest part of the collection was created. He was associated with the teaching community of the Königliches Marien-Gymnasium, an esteemed secondary school in Poznań (now St. Mary Magdalene High School). He established a relationship with Prof. Dr Friedrich Pfuhl (1853–1913), a specialist in plant anatomy (Brassicaceae: Brassica, Sinapis, and Raphanus) and the founder of Germany’s first school botanical garden. Szulczewski helped him with the careful selection of plant species for displaying them to the pupils.

After 1918, Szulczewski continued his scientific activity in liberated Poland. Prof. Pfuhl helped him to begin publishing in the journal Zeitschrift der Naturwissenschaftlichen Abteilung. His comprehensive mycological interest was evidenced by numerous 1–2-page notes and short references in the Zeitschrift. He also made a herbarium of plant teratology (e.g., [15]), as his attention was drawn to malformations of leaves and stems most often caused by the feeding of insects or the presence of their larvae inside plant tissues. Years later, he returned to this subject, incorporating his observations collected in the Wielkopolska National Park into a large article concerning plant leaf galls [16].

When Poland regained its independence after the First World War, as a sincere patriot he took on numerous social responsibilities. In 1919 the new, happiest chapter of Szulczewski’s life began in Poznań. He built a reputation as a scholar and scientist continuously expanding the scope of his activities. As a pedagogical manager at the Botanical Garden in Poznań, he supervised the programs and course of school excursions. At the same time, as a member of the Garden’s Board of Directors, he coordinated plant propagation on a large scale and implemented the idea of providing plants for teaching botany in all Poznań schools—was starting to be taught in Polish, using new curricula. He was a dedicated educator, participating in the work of the badly needed Polish textbook committee at the School District Board of Trustees in Poznań in 1919–1920. He tirelessly served as head of the Natural History Department of the Wielkopolska Museum. In recognition of his contributions, he was elected to be a member of the Physiographic Commission of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences (PAU) in Krakow in 1924 [11,17]. His collection from the year 1928 includes only 12 specimens of Ascomycetes. Much more numerous specimens were collected from 1960 to 1966 (POZM 0020604 to POZM 0020838, i.e., 228 records).

As an outstanding florist, ethnobotanist, physiographer, and passionate mycologist, Szulczewski became a member of a thriving center of Polish mycology. The Department of General Botany and Phytopathology at the University of Poznań gathered many esteemed scientists, such as Bolesław Namysłowski (1881–1929, mycologist and algologist), Karol Zaleski (1880–1969, phytopathologist, specialist in the genus Penicillium), and Tadeusz Dominik (1909–1980, specialist in mycorrhiza and mycotrophism of plant communities, talented painter and pioneer of microphotography). In 19311936, the mycologists gradually moved to the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the same university. In the POZM (M = mycology archive), the remaining two volumes from 1933 to 1934 of “Parasitic plant-fungi from Wielkopolska and Pomerania” were authored by T. Dominik. In addition, we found two volumes of plant pathogenic fungi collected by K. Zaleski in 1930 and fragments of “Mycotheca Polonica” authored by Marian Raciborski (1863–1917, paleobotanist and pteridologist), from 1900 to 1909, arranged by B. Namysłowski.

After the Second World War, Szulczewski devoted many years of work to the Committee for Nature Conservation. Under the difficult conditions of post-war Poland, he accelerated and expanded his research. Hidden from socialist reality in the Wielkopolska National Park, he documented the occurrence of various groups of organisms [16,18,19,20,21,22].

3. About the Fungarium

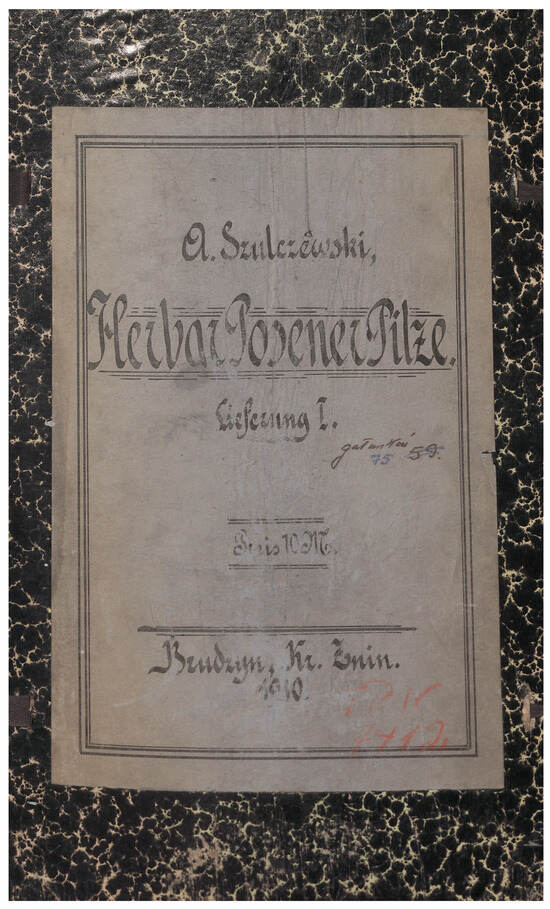

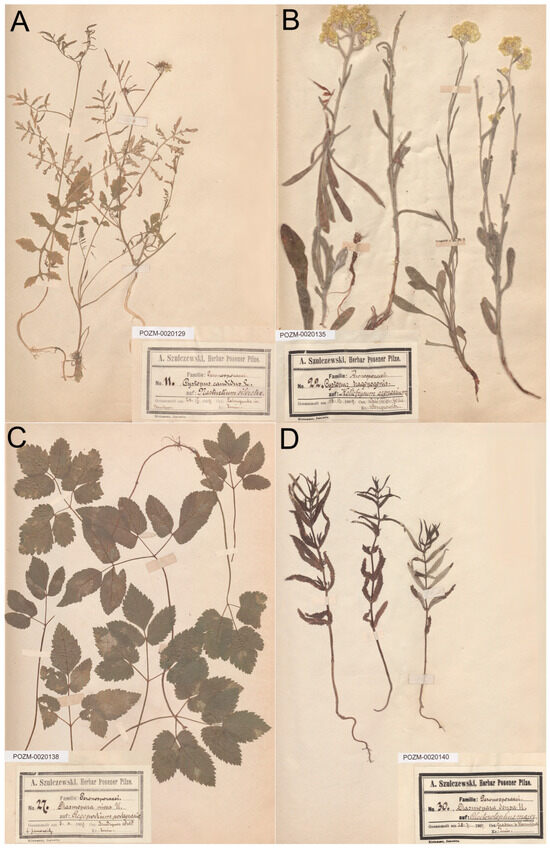

The collection contains around 300 sheets with plant pathogenic fungi belonging to the Oomycetes (currently classified as pseudofungi), Hyphomycetes, and Ascomycetes. A timeline of the collection was established, from the date of inclusion of the first sheet in 1909 until the last specimens in 1966. The material from 1909 to 1911, apart from its scientific value, bears the stamp of a typical 19th-century work, with calligraphic writing, decorative printed labels, and distinctive bookbinding of individual volumes (Figure 2). In a single sheet, 1–2 dried plants were mounted with glued strips and printed labels (with hand annotations), including the names of the pathogenic fungus and plant host (Figure 3A–D). The labels determined the sources of specimens and the time when they were added to the collection and are particularly valuable by the addition of the author’s detailed annotations.

Figure 2.

Decorative covers of the volume “Herbar Posener Pilze” 1911, containing plant pathogenic fungi described in an article of the same title in 1910.

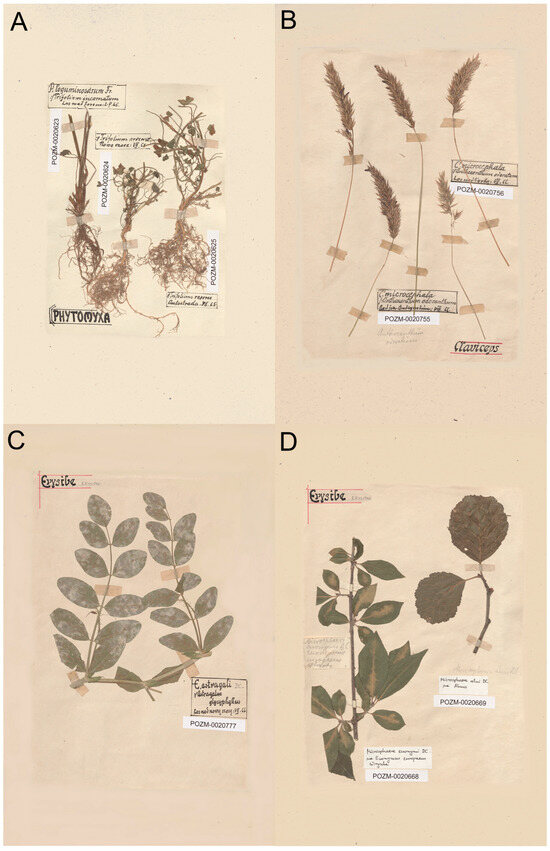

Figure 3.

Fungarium sheets from the 1910/1911 collection; (A) Cystopus candidus L. on Nasturtium silvestre R.Br. (B) Cystopus tragopogonis P. on Helichrysum arenarium (L.) Moensch. (C) Plasmopara nivea U. on Aegopodium podagraria L. (D) Plasmopara densa U. on Alechotorolophus maior Rchb. (now Rhinanthus serotinus (Schönh.) Oborny).

The fungarium specimens collected in 1909–1911 include 477 records of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants and about 300 pathogenic species (as POZM-0020123 to POZM-0020590) from 61 fungal families. The most numerously represented among them are the Pucciniaceae (61 species); Peronosporaceae (23); Erysiphaceae and Valsaceae (12 each), and Mycosphaerellaceae (10). Only 1 species was recorded in 19 families, and 11 families have 4 species each. The appendix contains a list of pathogens determined by Szulczewski, with the current scientific nomenclature according to Index Fungorum (Table S1).

In impoverished, post-war Poland, Szulczewski lacked high-quality paper and other materials to give his herbarium collections a proper binding. He hand-made the covers for the volumes; instead of printed labels, he wrote the names of fungi beneath the specimen, directly on the herbarium sheets. The collection grew rapidly to above 800 specimens in five volumes (1960–1966) (Figure 4 and Figure 5A–D). The fungarium has been traditionally managed and rarely used so far (Figure 6). For example, a pathogen whose symptoms were found on Pteridium growing in a forest in Wielkopolska in 2022 was compared with his specimen from 1966. This comparison made it possible to recognize and identify the pathogen repeatedly found in this region. This fact significantly broadens the spectrum of uses for the fungarium collection [23].

Figure 4.

Hand-made covers of the volume from 1960 to 1966, containing fungi collected in the Wielkopolska National Park.

Figure 5.

Fungarium sheets with plant pathogenic fungi collected in 1960–1966; (A) Phytomyxa leguminosarum Fr. on Trifolium arvense L. (B) Claviceps microcephala (Wallr.) Tul. on Anthoxanthum odoratum L.; (C) Erysiphe astragali DC on Astragalus glycyphyllos L.; (D) Microsphaera euonymii DC on Euonymus europaea L. and Microsphaera alni DC. on Alnus.

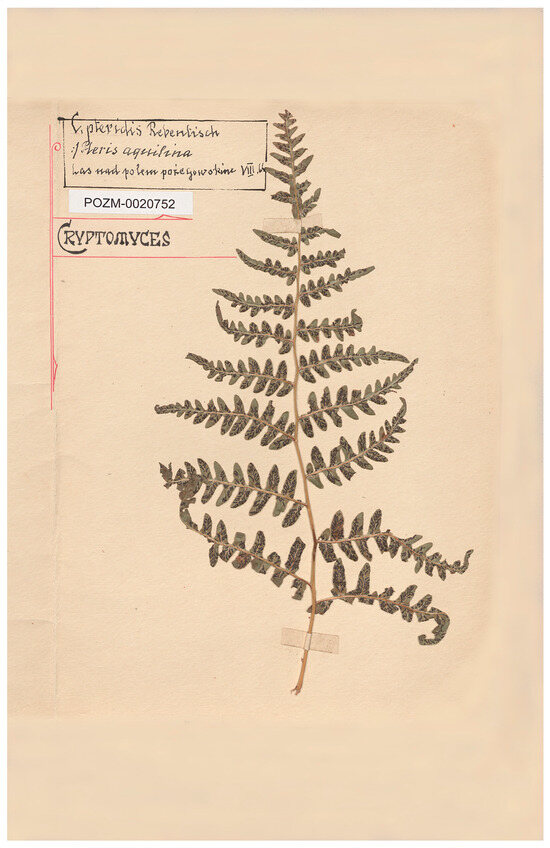

Figure 6.

Fungarium sheets of Pteris aquilina L. [Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn] collected by J.W. Szulczewski in September 1960, and used in the study on Cryptomycina pteridis (Rebent.) Syd. in Poland by [24].

The state of fungarium preservation was evaluated at the beginning of its digitization in 2023 and classified as satisfactory. On this occasion, it was noted that the whole collection was twice subjected to freezing at −30 °C. Currently, knowledge about Szulczewski’s fungarium existence is nearly absent in both Poland and Europe. This specialized collection is a floristic documentation of a specific geographic area, with the quantitative and qualitative state of the flora on the terrain once relatively untouched, but now becoming ecologically disturbed or devastated (flooding, fires, monoculture cultivation, development of tourism or road networks). The main value of Szulczewski’s fungarium is that it constitutes a repository of biological information, providing data on the historical diversity of plants and fungi in the Wielkopolska area. Also, Szulczewski’s surveys repeated for many years in a permanent plot are becoming increasingly important. Dried samples of plant pathogenic fungi deposited in fungarium could retain valuable wild-type sporulation and fruit bodies. In terms of documentary heritage, these materials already fall under the category of aDNA (ancient DNA) [25]. Dried herbarium samples sometimes do not provide good material for DNA extraction. Therefore, dried plant pathogenic fungi are given less attention by researchers, although the specimens may serve as long-lasting morphological comparative material for diagnosing some host-specific fungal species [26]. Nowadays, plant specimens collected in the POZ Herbarium (Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań) are used extensively, not only for taxonomic, biogeographic, phylogenetic, ecological, and genetic studies but also in other disciplines, such as phytopathology. The AMUNATCOLL project is creating a permanent digital record of the collections to allow online access for potential users [23].

The compiled list of fungal taxa completed now takes into account their current scientific names (Table S1).

4. Final Remarks

Among 3000 herbaria around the world, containing ca. 400 million specimens [27], herbaria with plant pathogenic fungi are not numerous. One of these is the Canadian National Mycological Herbarium (DAOM). The institution holds 227,000 fungal plant disease specimens, which document pathogens, toxigenic species, symbionts, saprophytes, and other organisms on various types of hosts, in different seasons of the year. The dried plant specimens with disease-causing fungi can be used for comparative purposes, taxonomic revision, and to collect information on conservation status and extinction risk trends concerning pathogenic fungi [28]. However, the largest fungarium is located at Kew and includes 60,000 digitized fungal specimens (available online) out of a total of ca. 1,250,0000 specimens from all over the world. To identify them precisely, researchers in Kew have used for a long time some rapid and low-cost DNA sequencing techniques.

In Poland, a database known as the “Register of protected and endangered fungi” was initiated in January 2005 and is available online Grzyby.pl [29]. It contains data on 382 taxa (species and varieties) of rare and protected fungi, present in 736 localities in only 122 out of the total of 3646 basic squares (10 km × 10 km) on the ATPOL grid. Among the reported taxa, 11 are new to Poland and 49 are very rare, known from only a few localities [30]. In addition, the private Błażej Gierczyk’s Fungarium (BGF) existed for several years but now his collection is deposited in the Warsaw University Herbarium.

The idea of protecting fungal biodiversity has long been pursued. A Polish register of GREJ (protected and endangered fungal species) has been created and after verification is periodically published in Przegląd Przyrodniczy (Natural History Review) as well as at www.bioforum.pl [30,31]. A critical list of Polish ascomycetes includes species that are extinct or have at most five modern sites. Documented years ago, Szulczewski’s Cryptomycina pteridis (Figure 6) has been on the list of GREJ for a long time [32].

Using state-of-the-art techniques, the Plant Protection Institute in Poznań has created a Pathogen Bank of about 2000 isolates of fungi and about 200 isolates of bacteria that cause diseases of crop plants in Poland. The collection is maintained to preserve the biodiversity of pathogen populations for the development of effective diagnostic and control methods. A list of the stored pathogens is available at Bankpat.expertus [33].

In conclusion, Szulczewski’s fungarium and all the other collections of pathogenic fungi mentioned here are invaluable sources of scientific data and material for further research, both theoretical and applied. Their digitization allows their broader use and facilitates searching for information needed for various purposes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d16070387/s1, Table S1: List of fungal taxa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z., Z.C., and P.S.; methodology, E.Z.; software, Z.C. and P.S.; validation, Z.C.; formal analysis, J.N.; investigation, E.Z.; resources, P.S. and J.N.; data curation, Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.Z. and Z.C.; visualization, Z.C. and P.S.; supervision, Z.C.; project administration, E.Z.; funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland (Research subsidy numbers 4102000000-604-506000-BN002024 and 4102020402-604-506000-BN002024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in the article and on the website https://amunatcoll.pl/.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bogdan Jackowiak, Head of the AMUNATCOLL Project (POPC.02.03.01-00-0043/18), who supported our research efforts to disseminate Szulczewski’s fungarium, and the curator of the herbarium for providing access to the collections, and to information. Thank to Krzysztof Stawrakakis for compiling the scans.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Acknowledgments. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Harris, Y.; Mullighan, M.; Brummit, N. Opportunities and challenges for herbaria in studying the spatial variation in plant functional diversity. Syst. Biodivers. 2021, 19, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carine, M.A.; Cesar, E.A.; Ellis, L.; Hunnex, J.; Paul, A.M.; Prakash, R.; Rumsey, F.J.; Wajer, J.; Wilbraham, J.; Yesilyurt, J.C. Examining the spectra of herbarium uses and user. Bot. Lett. 2018, 165, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Wingfield, M.J. Identifying and naming plant-pathogenic fungi: Past. present, and future. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015, 53, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenda-Kurmanow, M. Zielniki. Ochrona i konserwacja; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; 302p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.L.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Devos, J.; Shirsekar, G.; Reiter, E.; Gould, B.A.; Stinchcombe, J.R.; Krause, J.; Burbano, H.A. Temporal patterns of damage and decay kinetics of DNA retrieved from plant herbarium specimens. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AMUNATCOLL. Available online: https://amunatcoll.pl/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Jackowiak, B.; Lawenda, M.; Nowak, M.M.; Wolniewicz, P.; Błoszyk, J.; Urbaniak, M.; Szkudlarz, P.; Jędrasiak, D.; Wiland-Szymańska, J.; Bajaczyk, R.; et al. Open Access to the Digital Biodiversity Database: A Comprehensive Functional Model of the Natural History Collections. Diversity 2022, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowiak, B.; Błoszyk, J.; Dylewska, M.; Nowak, M.M.; Szkudlarz, P.; Lawenda, M.; Meyer, M. Digitization of and on line access to data from the natural history collections of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań: Assumptions and implementation of the AMUNATCOLL project. Biodiv. Res. Conserv. 2022, 65, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawenda, M.; Wiland-Szymańska, J.; Nowak, M.M.; Jędrasik, D.; Jackowiak, B. The Adam Mickiewicz University Nature Collections IT system (AMUNATCOLL): Metadata structure, database and operational procedures. Biodivers. Res. Conserv. 2022, 65, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.M.; Lawenda, M.; Wolniewicz, P.; Urbaniak, M.; Jackowiak, B. The Adam Mickiewicz University Nature Collections IT system (AMUNATCOLL): Portal, mobile application and graphical interface. Biodivers. Res. Conserv. 2022, 65, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzięczkowski, A. Jerzy Wojciech Szulczewski (1879–1969). Kujawsko-Wielkopolski etnograf, fizjograf i pedagog; Polskie Towarzystwo Turystyczno-Krajoznawcze, Oddział w Strzelnie: Strzelno, Poland, 1977; 15p. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Beitrag zur Pilzflora von Brudzyn im Kreise Znin. Zeitschr. Naturwiss. Abteil. 1909, 15, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Verzeichniss zum Herbar der Posener Pilze. Zeitschr. Naturwiss. Abteil. 1910, 16, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fries, E.M. Systems Mycologicum, Sistens Fungorum Ordines, Genera et Species, huc Usque Cognitas, Quas ad Normam Methodi Naturalis Determinavit; Ex Officina Berlingiana: Lundae, Sweden, 1832; Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Aus meinen teratologischen Herbar. Zeitschr. Naturwiss. Abteil. 1911, 23, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Wyrośle Wielkopolskiego Parku Narodowego. Pr. Monogr. Przyr. WPN pod Poznaniem. 1950, 2, 141–178. [Google Scholar]

- Górska-Zajączkowska, M. Poznański Ogród Botaniczny 1925–2005. Historia i ludzie; Bogucki Wyd. Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2006; 36p. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Fauna naśnieżna Wielkopolskiego Parku Narodowego. Pr. Monogr. Przyr. WPN pod Poznaniem. 1947, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Błonkówki (Hymenoptera) WPN. cz. 3, Pszczołowate: (Apidae). Pr. Monogr. Przyr. WPN pod Poznaniem. 1948, 2, 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Wykaz roślin naczyniowych w Wielkopolsce dotąd stwierdzonych. PTPN Pr. Kom. Biol. 1951, 12, 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Śluzowce Wielkopolskiego Parku Narodowego. Pr. Monogr. Przyr. WPN pod Poznaniem. 1951, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Szulczewski, J.W. Obcy element w roślinności Wielkopolskiego Parku Narodowego. Pr. Monogr. Przyr. WPN pod Poznaniem. 1963, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jackowiak, B.; Błoszyk, J.; Celka, Z.; Konwerski, S.; Szkudlarz, P.; Wiland-Szymańska, J. The natural history collections of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (Poland): An outline of their history and content. Biodivers. Res. Conserv. 2022, 65, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenkteler, E.; Celka, Z.; Szkudlarz, P.; Grzegorzek, P. Fungal endophyte Cryptomycina pteridis (Rebent.) Syd. on the native fern Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn in Poland. Biodivers. Res. Conserv. 2023, 72, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, F.T. Herbarium genomics: Plant archival DNA explored. In Paleogenomics. Population Genomics; Lindqvist, C., Rajora, O.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Rossman, A.Y.; Aime, M.C.; Burgess, T.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Castlebury, L. Names of phytopathogenic fungi. A practical guide. Phytopathol. 2021, 11, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiers, B.M.; Tulig, M.C.; Watson, K.A. Digitization of the New York Botanical Garden Herbarium. Brittonia. 2016, 68, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, W.; Crompton, C.W. The biology of Canadian weeds. 15. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Can. J. Plant. Sci. 1975, 55, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzyby.pl. Available online: https://www.grzyby.pl (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Gierczyk, B.; Kujawa, A. Rejestr grzybów chronionych i zagrożonych w Polsce. Część XI. Wykaz gatunków przyjętych do rejestru w roku 2015. Przeg. Przyr. 2023, 24, 3–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa, A.; Gierczyk, B.; Gryc, M.; Wołkowycki, M. Grzyby Puszczy Knyszyńskiej; Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Puszczy Knyszyńskiej Wielki Las, Park Krajobrazowy Puszczy Knyszyńskiej: Supraśl, Poland, 2019; 215p. [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel, M.A. Checklist of Polish larger Ascomycetes; W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Science: Kraków, Poland, 2006; 152p. [Google Scholar]

- Bankpat.expertus. Available online: https://bankpat.expertus.com.pl/search/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).