Abstract

In this study, we present the relationships between total length, unburied length, and shell width and between total length and net weight for the critically endangered Pinna nobilis. This is the first transplantation study in which live specimens of P. nobilis have been used for estimating the length–weight relationship by deploying the unburied length. Length–length relationships were all linear for all cases (r2 > 0.900), whereas the length–weight relationship was negative allometric with the values of the exponent b ranging from 2.159 to 2.828. These relationships are important because they offer a restorative monitoring tool without damaging or sacrificing this endangered species, as total length can be computed using unburied length. By examining the relationships between different size dimensions in this re-allocated population, the present study also provided valuable insights for comparative growth studies, stock assessment models, and conservation purposes.

1. Introduction

Pinna nobilis (Linnaeus, 1758) is the largest endemic Pteriomorphian bivalve in the Mediterranean Sea, reaching lengths of up to 120 cm. Over the past three decades, populations of P. nobilis have significantly declined due to factors such as consumption for food or ornaments, as well as the negative impact of trawling and boat anchoring [1]. To protect this species, it is covered by the Mediterranean Specially Protected Areas protocol (95/96 SPA ANNEX II) and European legislation (92/43 EEC). P. nobilis has recently been classified as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of threatened species. One of the main challenges faced by P. nobilis populations is the impact of a protozoan parasite called Haplosporidium pinnae [2]. This parasite has caused mass mortality events and increased the risk of extinction in many of the habitats where this species is found. The devastating effects of this parasite have been observed in various countries including France, Italy, Tunisia, Turkey, Greece, and even in one of the last remaining safe shelters for the fan mussel in Croatia [3].

The present study focused on the morphometric analysis of P. nobilis population reallocated for conservation purposes in the Maliakos Gulf (Central Aegean, Greece). By examining the relationships between different size dimensions in this particular population, we would provide valuable insights for comparative growth studies, stock assessment models, and conservation purposes [4,5]. To our knowledge, no information is currently available in the SealifeBase (www.sealifebase.or) (accessed on 5 July 2023) ([6] on the above-mentioned relationships, and only a few relationships have so far been estimated for the species in the Mediterranean (Corse: [7]; Greek Lake: [8]; Turkish waters: [9]; Spain: [7,10,11]. This is the first study in which live specimens of P. nobilis have been used for estimating the length–weight relationship by deploying the unburied length. These relationships are important because they offer a restoration monitoring tool for the environment and the organism without damaging or sacrificing this critically endangered species, as total length can be computed using unburied length.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

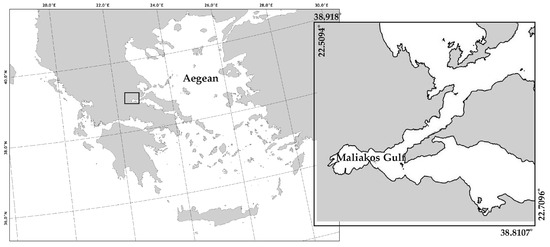

Maliakos Gulf is located on the eastern side of mainland central Greece and part of the Aegean Sea (Figure 1; more characteristics of the area can be found in [5,12]). The fan mussel was widely distributed in the coastal zone until 2020, having the anterior part of the shell partially buried in soft or hard substrata, and it is attached by threads of its byssus [12]. For a pilot study regarding the transplantation of P. nobilis, local divers removed 100 lived specimens covering all visible mollusk sizes. After the careful removal of mollusks from their natural habitat, paying attention not to lose the byssus threads, certain morphometric and weight parameters were measured were measured on board: total length (TL, in cm), unburied length (UL, in cm), shell width (SW, in cm), and net weight (NW, in g) (Figure 2). All length measurements were taken with an accuracy of 0.1 cm and weight with accuracy of 100 g. The accuracy of the weight measurements was controlled by the fact that these measurements were taken on board as part of a transplant experiment, for which we had no intention of harming the specimens.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area. Black frame indicate the area of the sampling.

Figure 2.

Morphometric measurements taken for Pinna nobilis in the field.

2.2. Data Analysis

Length–length relationships were estimated using the linear regression Y = a + bX, and length–weight relationship was estimated through the relationship W = a × Lb [13], where W is the wet weight, L the length, and coefficients a and b are the intercept of the curve on the weight axis and the slope of the line in the linear slope of the equation, respectively. The findings of the present study were also compared with those from the literature to investigate the area effect on these relationships.

3. Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics of the morphometric measurements are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the morphometric measurements for all specimens of Pinna nobilis sampled in Maliakos Gulf (Central Aegean, Greece) in 2019.

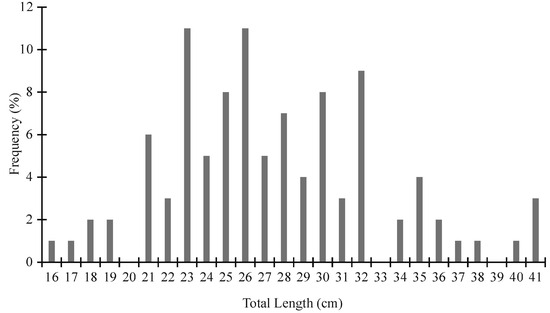

The length class of the sampled specimens peaked at 23 and 26 cm (Figure 3). Considering the fact that the total length of 20 cm represents the threshold value under which individuals should be considered juveniles [14,15], we could assume that all sampled individuals were mature.

Figure 3.

Length frequency distribution for the alive specimens of Pinna nobilis sampled in Maliakos Gulf (Central Aegean, Greece) in 2019.

All length–length relationships were significant (all r2 > 0.425, p < 0.05), with r2 values ranging from 0.472, for the relationship between UL and SW, to 0.804, for the relationship between TL and UL (Table 2). TL and UL relationships with NW were highly significant (p < 0.001) with r2 values being 0.836 and 0.759, respectively (Table 3). These relationships were also negative allometric, with the values of the exponent b being 2.233 and 2.572, respectively (Table 3). Contrarily with our results, ref. [8] reveals that the TL-W relationships followed a positive allometric growth. Apart from the exponential regression, the authors of [1], to determine the relationship between TL and SW, apply a second-degree polynomial function.

Table 2.

Morphometric relationships between total length (TL, cm) and shell width (SW, cm), unburied length (UL, cm) and shell width (SW, cm) and total length (TL, cm) and unburied length (UL, cm), for all specimens of Pinna nobilis sampled in Maliakos Gulf (Central Aegean, Greece) in 2019. n is the sample size; a and b are the parameters of the linear regression.

Table 3.

Length–weight relationship (W = a × TLb) between total length (TL, cm) and -net weight (NW, g) and unburied length (UL, cm) and net weight, for all specimens of Pinna nobilis sampled in Maliakos Gulf (Central Aegean, Greece) in 2019. n is the sample size, a and b are the parameters of the length-weight relationship and r2 is the coefficient of determination.

Six equations on the morphometric characteristics of P. nobilis have been established so far, but none of them estimated the relationships with UL (Table 4). In the present study, the relationships incorporated the UL might be useful for estimating the TL and the weight, because the measurement of the UL is a non-destructive sampling method. Differences in morphometric estimation could be attributed to the combination of one or more of the following factors: (a) differences in the number of specimens examined, (b) area/season effect, (c) differences in the observed length ranges of the specimen measured, and (d) abiotic factors such as temperature, salinity, wave regime, surrounding vegetation, and substrate type.

Table 4.

Estimated parameters of the relationships on the morphometric parameters for Pinna nobilis estimated in the Mediterranean. TL is the total length in cm; SW is the shell width in cm; W is the width at depth level in cm; NW is the net weight in g; and UL is the unburied length in cm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.T.; methodology, I.E.T. and D.K.M.; resources, I.E.T., D.D.R., A.L. and I.A.G.; data curation, I.E.T., D.D.R., A.L. and I.A.G.; writing—review and editing, I.E.T., D.K.M., A.L., I.A.G., B.M. and J.A.T. supervision, I.E.T., D.K.M. and J.A.T.; project administration, B.M. and J.A.T.; funding acquisition, J.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was part of the project “Innovative Actions for the Monitoring-Recovery—Enhancement of the Natural Recruitment of the Endangered Species (Fan mussel) Pinna nobilis”, funded by the Operational Programme for Fisheries and Maritime 2014–2020 (Measure 6.1.16) and EMFF, grant number (MIS) 5052394.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request made to the last author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to masters and crew of the fishing vessels “KAPETAN STRATIS”, “ELENI”, “AGIOS DIMITRIOS”, “MEGALOHARI” and “CHRYSOULA”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Katsanevakis, S. Transplantation as a conservation action to protect the Mediterranean fan mussel Pinna nobilis. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 2016, 546, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupé, S.; Giantsis, I.A.; Luis, M.V.; Scarpa, F.; Foulquié, M.; Prévot, J.-M.; Casu, M.; Lattos, A.; Michaelidis, B.; Sanna, D.; et al. The characterization of toll-like receptor repertoire in Pinna nobilis after mass mortality events suggests adaptive introgression. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čižmek, H.; Čolić, B.; Gračan, R.; Grau, A.; Catanese, G. An emergency situation for pen shells in the Mediterranean: The Adriatic Sea, one of the last Pinna nobilis shelters, is now affected by a mass mortality event. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2020, 173, 107388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorou, J.A.; James, R.; Tzοvenis, I.; Hellio, C. The recruitment of the endangered fan mussel (Pinna nobilis, Linnaeus 1758) on the ropes of a Mediterranean mussel long line farm. J. Shell. Res. 2015, 34, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, J.A.; James, R.; Tagalis, D.; Tzovenis, I.; Hellio, C.; Katselis, G. Density and size structure of the endangered fan mussel Pinna nobilis, in the shallow water zone of Maliakos Gulf, Greece. Acta Adriat. 2017, 58, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, M.L.D.; Pauly, D. (Eds.) SeaLifeBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. 2023. Available online: www.sealifebase.org (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- De Gaulejac, B.; Vicente, N. Ecologie de Pinna nobilis (L.) mollusque bivalve sur les côtes de Corse. Essais de transplantation et expériences en milieu contrôlé. Haliotis 1990, 10, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Katsanevakis, S. Population ecology of the endangered fan mussel Pinna nobilis in a marine lake. Endanger. Species Res. 2006, 1, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarli, S.; Lok, A.; Yigitkurt, S.; Palaz, M. Culture of fan mussel (Pinna nobilis, Linnaeus 1758) in relation to size on suspended culture system in Izmir Bay, Aegean Sea, Turkey. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fakültesi Derg. 2011, 17, 995–1002. [Google Scholar]

- García-March, J.R.; Ferrer, J.F. Biometría de Pinna nobilis L., 1758: Una revisión de la ecuación de De Gaulejac y Vicente (1990). Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 1995, 11, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-March, J.R.; Vicente, N. Protocol to Study and Monitor Pinna nobilis Populations within Marine Protected Areas. Report of the Malta Environment and Planning Authority (MEPA) and MedPAN-Interreg IIIC-Project. 2006. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/131bRQrcQQ62NUep1V1J3f_W33JAmANbO/view (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Zgouridou, A.; Tripidaki, E.; Giantsis, I.; Lattos, A.; Raitsos, D.; Anestis, A.; Theodorou, J.A.; Kalaitzaki, M.; Feidantsis, K.; Staikou, A.; et al. A survey on the microbial load on edible and economical important marine bivalve species in the Greek Seas. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 24, 1012–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Cren, E.D. The length–weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in perch (Perca fluviatilis). J. Anim. Ecol. 1951, 20, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Vicente, N.; de Gaulejac, B. Ecology of the pterioid bivalves Pinna bicolor Gmelin and Pinna nobilis L. Mar. Life 1993, 3, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C.A.; Kennedy, H.; Duarte, C.M.; Kennedy, D.P.; Proud, S.V. Age and growth of the fan mussel Pinna nobilis from south-east Spanish Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) meadows. Mar. Biol. 1999, 133, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, M.; Del Piero, D.; Ciriaco, S. Definition of a new formula for the calculation of the total height of the fan shell Pinna nobilis in the Miramare marine protected area (Trieste, Italy). Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2013, 23, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).