Abstract

We present the diversity of Asteraceae in the Arequipa Region of southern Peru, an area strongly influenced by volcanism, which has given rise to different soil types and has determined a very wide bioclimatic and vegetational zonation. We present the distribution of Asteraceae endemisms of Peru and Arequipa, and of the dry puna. For this purpose, we have used the bioclimatic methodology of Rivas-Martínez, the characteristic soils of each collection point, and the distance of the collection localities from the volcanoes. In the Arequipa Region, we found 232 species of Asteraceae, of which 49 are endemic to Peru or to the dry puna and 7 are endemic to the studied area. Of these endemics, 10 are thermotropical, 1 is mesotropical, 3 are supratropical, and 3 are orotropical bioindicators, being mainly distributed in two large groups of soils: sandy and saline or gypsiferous soils, mostly located within the thermotropical belt of the coastal desert, and andosols and cambisols distributed from the thermotropical to the cryorotropical belts of the Andes. The greatest number of endemics and semi-endemics are found in the vicinity of the arc formed by the Misti, Chachani and Pichu-Pichu volcanoes.

1. Introduction

The Asteraceae family, together with the Orchidaceae, Poaceae, and Piperaceae, is one of the most diverse families in Peru [1]. The most recent list of the New World Flora [2] reported 1474 species of Asteraceae, although various taxonomic studies led to a reduction to 1244 between synonymies and species absent from the Peruvian territory [3,4].

Perhaps the first author to synthetically study the Asteraceae in southern Peru was Weddell [5], including genera such as Mutisia L.f., Perezia Lag., Plazia Ruiz & Pav. or Werneria Kunth (=Rockhausenia D.J.N. Hind), based on the work of post-Linnaean authors such as Linnaeus filius, Ruiz and Pavón, Humboldt et al., or Lessing [6,7,8,9]. Without forgetting the data of Weberbauer [10] in southern Peru, with the ecological behavior of Ambrosia, Diplostephium Kunth, Grindelia Willd., Lepidophyllum Cass. (=Parastrephia Nutt.), Onoseris Willd., Proustia Lag. Or Senecio L., we have added numerous contributions restricted to certain groups or genera, such as Chersodoma Phil. [11], Mutisia [12,13], Gochnatia Kunth [14], Plazia [15], Senecio [16,17,18,19]), Werneria (=Rockhausenia) [20,21], Xenophyllum V.A. Funk (=Werneria) [21,22,23], and to floristic and vegetational studies [24].

The Arequipa Region is located in southern Peru, between the coordinates 15°11′45.72″ S/73°27′54.70″ W and 16°47′08.93″ S/70°03′51.28″ W, longitudinally, and 14°37′51.08″ S/71°59′04.75″ W and 16°35′21.08″ S/72°47′05.95″ W, transversely, and presents six large areas with habitat types of different climatic characters: (a) coastal desert hills (‘lomas’) with ephemeral vegetation and isolated Cactaceae (0–1000 m a.s.l.), (b) inter-desert barrier as a large plain with Quaternary fluvial and aeolian sedimentation only with the vegetation of the streams (1000–2000 m a.s.l.), (c) western Andean slopes with Cactaceae and shrub communities (2000–3100 m a.s.l.), (d) western Andean slops with mesophytic shrubs (3100–3800 m a.s.l.), (e) volcanic reliefs with deep soils of the dry highlands with shrubs and grasslands (‘dry puna’), the humid highlands with a predominance of grasslands (‘humid puna’) (3800–4800 m a.s.l.), and (f) the coldest areas with cryogenic processes with small grasslands, usually above 4800 m a.s.l. [25]. These landscape units reach their greatest extensions in the Arequipa Region with respect to others in Peru, with volcanic soils and morphology, making it a model area for establishing ecological relationships in various plant families.

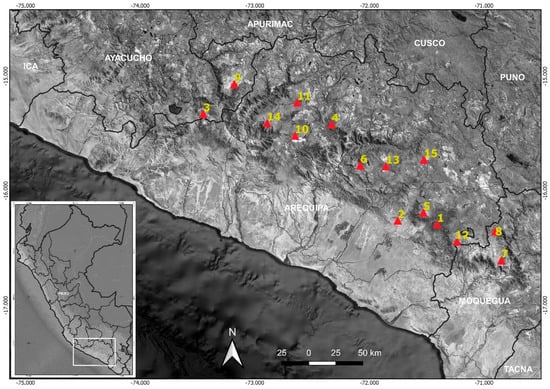

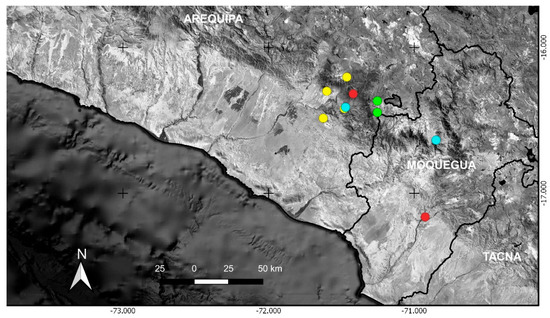

Volcanoes have undoubtedly marked the landscape of Arequipa with super-eruptions dating back 490 million years (Ordovician) [26], Pleistocene stratovolcanoes (2.59 m.y. BP) [27], such as the Chachani complex [28]), with relatively modern eruptions, such as those of Misti in the 15th century [27], Huaynaputina, in the 17th century (Moquegua Region) [29] or Sabancaya at present (Figure 1). The Pichu-Pichu volcano represents an older geomorphological pattern, as it is known to have been active 6.7 m.y. ago (Miocene) and part of it collapsed 1 m.y. ago [30,31].

Figure 1.

Distribution map of the volcanoes of the Arequipa Region, northwestern Moquegua Region and southwestern Ayacucho: 1: Misti, 2: Cerro Nicholson, 3: Sara-Sara, 4: Andahua-Orcopampa, 5: Chachani, 6: Huambo, 7: Huaynaputina, 8: Ubinas, 9: Cerro Auquihuato, 10: Coropuna, 11: Nevados Firura, 12: Pichu-Pichu, 13: Sabancaya, 14: Solimana, 15: Huarancante.

Several studies have revealed the relationship between plant diversity, climatic factors, soil types, and volcanic activity in different parts of the world [32,33,34,35]. Dimopoulos et al. [32] indicated that areas more distant from the most modern volcanism have the highest floristic diversity, while materials derived from the most modern volcanism have a low diversity and tend to be terophytes or bisannuals. Schwarzer et al. [33] studied the distribution and dispersal of plants due to the Huaynaputina super-eruption, concluding that some species had dispersed from very distant Andean areas from Argentina or Chile to southern Peru with the substrate originated by the eruption having a strong influence. Ghermandi et al. [34] comparing plant composition before and after a volcanic eruption in Patagonia observed that plant cover is higher in areas with volcanic ash than in areas without volcanic ash, and that ash deposition removes exotic terophytes but increases the presence of geophytes. Martín Osorio et al. [35] studied the colonising vegetation in a recent eruption on the Canary Island of Tenerife, observing a high number of endemic species in the lower vegetation belts.

The aim of this work was to obtain an updated catalogue of the species of Asteraceae in the Arequipa Region, establishing the distribution patterns of its endemisms and semi-endemisms in relation to bioclimatology, soil types, and volcanism in order to identify future conservation areas within the territory studied.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Studying and Arranging Herbarium Vouchers

To know the number of Asteraceae species growing in the Arequipa Region, 2206 herbarium sheets from the CUZ, F, HBG, HUSA, K, MA, MO, NY, P, US, and USM herbaria (acronyms following Thiers, continuously updated [36]) were studied. For each, the locality, collector and collection number, month, year, altitude, and coordinates were detailed (Supplementary Table S1). The Asteraceae of Arequipa with the distribution in other Peruvian regions (Supplementary Table S2) were extracted from the Supplementary Table S1 in order to discover which are the endemisms and semi-endemisms of the territory studied.

Endemisms are species that inhabit within the borders of the Peruvian territory or the Arequipa Region, while semi-endemisms are species distributed throughout the regions of Ica, Ayacucho, Arequipa, Moquegua, and Tacna in Peru, even though they extend to Bolivia, Chile and Argentina; they are species that are spread throughout the driest part of the Andes, from the Ica Region to the highlands of Bolivia, Chile and Argentina (Xerophytic Punenian biogeographic province) according to the biogeographical sectorisation by Rivas-Martínez et al. [37].

Appendix A, Table A1 are the species of non-repeated localities of the database (Supplementary Table S1) with decimal coordinates and is a synthesis of Supplementary Table S3. Decimal coordinates were also used to generate the distribution maps of the Figures 1, 8, and 9 with the Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) 3.0.1 [38].

2.2. Bioclimatic Characterization of Plants

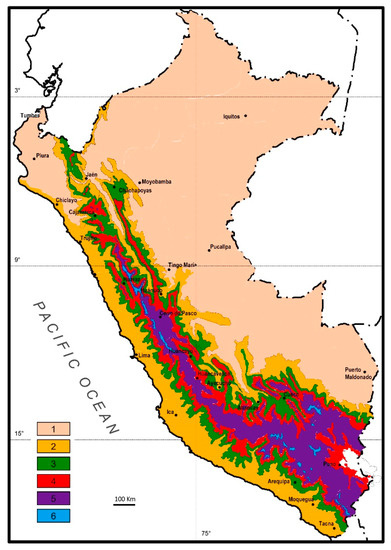

To bioclimatically characterise the locality of each herborised specimen, we used the Rivas-Martínez model of bioclimatic belts [39]. Bioclimatic belts are based on thermicity index (It) ranges and bioindicators, which are plants and associations of vegetation. The thermicity index is a mathematical expression containing different temperature values in degrees centigrade: It = (T + M + m) 10 [T: Average annual temperature, M: Average maximum temperature in the coldest month, m: Average minimum temperature of the coldest month]. At present, we are able to distinguish six bioclimatic belts or thermotypes throughout Peru (Figure 2, [40]): Infratropical (It > 690), thermotropical (It = 490 to 690), mesotropical (It = 320 to 490), supratropical (It = 160 to 320), orotropical (It = 50 to 160), and cryorotropical (It = < 50). These belts are nuanced by rainfall intervals (annual P in mm) or ombrotypes, so we can observe a very humid thermotropical belt in the Amazon but be very dry in Southern Peru. We can distinguish nine types of precipitation intervals in the country: Ultrahyperarid (P < 5), hyperarid (5 to 30), arid (31 to 100), semiarid (101 to 300), dry (301 to 500), subhumid (501 to 900), humid (901 to 1500), hyperhumid (1501 to 2500), and ultrahyperhumid (>2500). In Arequipa, the bioclimate fluctuates from thermotropical ultrahyperarid to cryorotropical humid [41].

Figure 2.

Bioclimatic belts in Peru according to Galán-de-Mera et al. (modified) [40]. 1: Infratropical, 2: Thermotropical, 3: Mesotropical, 4: Supratropical, 5: Orotropical, 6: Cryorotropical.

Meteorological data, with a time frame of 30 years, were taken from METEOBLUE [42], establishing comparisons in some cases with the results of the CHELSA database [43]. These computer tools make it possible to obtain meteorological values and climate diagrams for any coordinate, which increases the accuracy of the relationship between a species and certain bioclimatic indices and parameters.

2.3. Plants, Soils and Volcanism

To observe the influence of soil types on the flora, we used SoilGrids database [44] by matching the coordinates of the localities where specimens were collected with those of the corresponding pixel which indicates the percentage of soil types. According to IUSS Working Group WRB [45], we have distinguished 13 soil types in the Arequipa Region (Appendix A, Table A1; Supplementary Table S3): Andosols: volcanic soils par excellence, formed on ashes, volcanic glasses, or from pyroclasts (they are found in regions with active or recent volcanism, that is, in the vicinity of volcanic cones); arenosols: sandy soils; regosols: soils with no significant profile development; leptosols: shallow or extremely gravelly soils; calcisols: soils with accumulation of calcium carbonate; cambisols: moderately developed soils; luvisols: soils with a clay-enriched subsoil, with a high base status and high-activity clay; fluvisols: floodplains and tidal marshes; solonchaks: soils with salt enrichment upon evaporation; gypsisols: soils with accumulation of gypsum; kastanozems: soils of dry climate, with accumulation of organic matter phaeozems: soils of more humid climate, with accumulation of organic matter; and vertisols: soils influenced by water, alternating wet-dry conditions and rich in swelling clays.

In addition, to test the possible tendency of flora distribution versus volcanism, we calculated the distance between the localities of the specimens and the base of the Arequipa volcanoes (DIST) (Appendix A, Table A1; Supplementary Table S3) using the database of the Global Volcanism Program of Smithsonian Institution [46]. From this database, it is possible to obtain a kml file visible using the Google-Earth portal [47]. For this purpose, localities between 0 and 50 km were separated from localities between 50 and 150 km, since 50 km is the approximate distance between the coastline and the beginning of the western Andean slope.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To observe the tendency of the distribution of 138 collected specimens in relation to their altitude (H), climatic variables and indices (T, M, m, It, P), distance to the nearest volcanoes (DIST), and percentages of the soils found in the pixel of a given locality, we used a principal component analysis (PCA) based on a matrix with the numerical data of the Appendix A, Table A1, or Supplementary Table S3. Eingenvectors indicate how the variables correlate with the location of the specimens. To see how the different variables are correlated, a correlation matrix was carried out using Pearson’s parametric test. These statistical analyses were run with the PAST 4.07b software [48].

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of Asteraceae in the Arequipa Region

Among the 2206 herbarium sheets studied (Supplementary Table S1), 232 species belonging to 82 genera of the Asteraceae family from the Arequipa Region were extracted (Supplementary Table S2), of which 49 are Peruvian endemics or semi-endemics of the Xerophytic Punenian biogeographic province: Ageratina lobulifera (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King and H. Rob., Aldama dilloniorum (A.J.Moore and H. Rob.) E.E.Schill. and Panero, A. peruviana (A. Gray) E.E.Schill. and Panero, Ambrosia dentata (Cabrera) M. O. Dillon, *A. pannosa W.W.Payne, Aristeguietia ballii (Oliv.) R.M.King and H. Rob., A. cursonii (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King and H. Rob., Baccharis scandens (Ruiz and Pav.) Pers., Chersodoma juanisernii (Cuatrec.) Cuatrec., Chionopappus benthamii S. F. Blake, Erigeron incaicus Solbrig, E. leptorhizon DC., Gochnatia arequipensis Sandwith, *Heiseria irmscheriana (Bruns) Mesfin, *Helogyne hutchisonii R.M.King and H. Rob., Heterosperma ferreyrii H. Rob., Lomanthus arnaldii (Cabrera) B. Nord. and Pelser, L. icaensis (H.Beltrán and A. Galán) B. Nord., L. lomincola (Cabrera) B. Nord. and Pelser, *L. mollendoensis (Cabrera) B. Nord., L. okopanus (Cabrera) B. Nord., L. subcandidus (A. Gray) B. Nord., L. tovarii (Cabrera) B. Nord. & Pelser, Munnozia lyrata (A. Gray) H. Rob. and Brettell, Mutisia arequipensis Cabrera, Nordenstamia longistyla (Greenm. and Cuatrec.) B. Nord., Onoseris minima Domke, O. odorata (D. Don) Hook and Arn., Ophryosporus bipinnatifidus B.L.Rob., O. pubescens (Smith) R.M.King and H. Rob., *Paquirea lanceolata (H.Beltrán and Ferreyra) Panero and S. Freire, Philoglossa peruviana DC., Senecio acarinus Cabrera, S. beltranii P. Gonzáles and Montesinos, S. chachaniensis Cuatrec., S. crassilodix Cuatrec., S. flaccidifolius Wedd., S. gamolepis Cabrera, S. hebetatus Wedd., S. neoviscosus Cuatrec., *S. smithianus Cabrera, S. yurensis Rusby, S. cuzcoensis Hieron., S. hoppii B.L.Rob., S. melissiaefolia (Lam.) Sch.Bip., S. puberula Hook., S. weberbaueri B.L.Rob., Syncretocarpus sericeus (DC.) S. F. Blake, and *Wedelia hoffmanniana F.Bruns. The seven species marked with an asterisk are endemic to Arequipa. W. hoffmanniana has not been collected since 1923 (sheet Gunther 46, HBG).

We consider the following species as semi-endemic or endemic to the Xerophytic Punenian biogeographic province (Appendix A, Table A1; Supplementary Table S3): Aldama dilloniorum, Ambrosia dentata, A. pannosa, Aphyllocladus denticulatus (J.Rémy ex Gay) Cabrera, Aristeguietia cursonii, Diplostephium meyenii Wedd., Gochnatia arequipensis, Helogyne apaloidea Nutt., Lomanthus icaensis, L. mollendoensis, L. okopanus, Lophopappus cuneatus R.E.Fr., L. foliosus Rusby, Mutisia arequipensis, M. orbignyana Wedd., Onoseris minima, Ophryosporus bipinnatifidus, O. hoppii (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King and H.Rob., Pluchea absinthioides (Hook. and Arn.) H.Rob. and Cuatrec., Polyachyrus annuus I.M.Johnst., Senecio calcicola Meyen and Walp., S. crassilodix, S. neoviscosus, S. scorzonerifolius Meyen and Walp., S. yurensis, and Werneria esquilachensis Cuatrec.

The genus Chionopappus Benth., Heiseria E.E. Schill and Panero and Paquirea Panero and S.E. Freire are endemic to Peru. Paquirea genus is endemic to Arequipa only.

3.2. Distribution Patterns

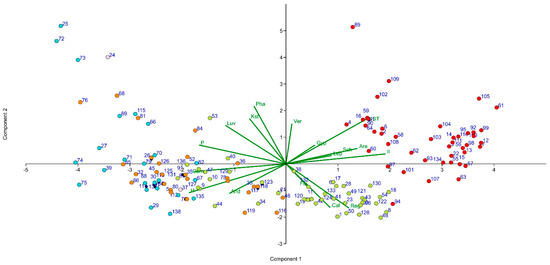

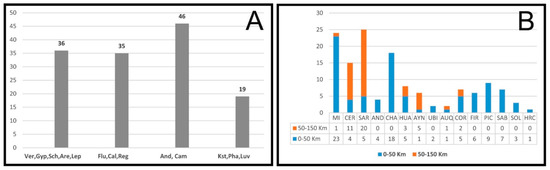

In the PCA (Figure 3), specimens are arranged along the axes according to altitude (H) (Component 1) and Thermicity Index (It) (Component 2). Precipitation trends higher towards the negative values of Component 2, while the Thermicity Index (It) trends higher towards the positive values of the x-axis. Thus, species located further to the right of the ordinate axis are found in the thermotropical bioclimatic belt, while those located further to the left are found in the supra- and orotropical belts. This means that the distances to volcanoes, combined with very low rainfall and a higher thermicity index (It) and, in turn, with Arenosols (Are), Gypsisols (Gyp), Solonchaks (Sch) and Leptosols (Lep) denote the species that are concentrated on the thermotropical coastal belt. These species include Lomanthus icaensis (57), and L. mollendoensis (58,61,62), Ophryosporus bipinnatifidus (89), Polyachyrus annuus (102,103,104), and Senecio calcicola (109,110,111).

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) correlating endemisms and semi-endemisms collected in Arequipa with altitude (H), precipitation (P), thermicity index (It), distance to volcanoes (DIST), and soil types (And: Andosols, Are: Arenosols, Reg: Regosols, Lep: Leptosols, Cal: Calcisols, Cam: Cambisols, Luv: Luvisols, Flu: Fluvisols, Sch: Solonchaks, Gyp: Gypsisols, Kst: Kastanozems, Pha: Phaeozems, Ver: Vertisols). Component 1 and 2 comprise 33.28% and 12.504% of the variance respectively. Bioclimatic belts: thermotropical (red dots), mesotropical (green dots), supratropical (orange dots), orotropical (light blue dots), cryorotropical (lilac dots).

In the lower right quadrant of the PCA, there are species of the lower mesotropical belt, with slightly more precipitation, poorly consolidated soils (Regosols, Reg) and accumulations of calcium carbonate (Calcisols, Cal) from the Jurassic and Cretaceous of Arequipa. Among the species, we found Aldama dilloniorum (8), Ambrosia pannosa (1), Aphyllocladus denticulatus (18,19), Gochnatia arequipensis (48,50), Helogyne apaloidea (54), Senecio yurensis (120,128,130,133). Here we also found thermotropical species, generally from the coast, established with a certain probability on regosols and calcisols, such as Lomanthus okopanus (63), Ophryosporus hoppii (94), Polyachyrus annuus (101), and Senecio calcicola (107). In this quadrant we also found Pluchea absinthioides (97), typical of thermo-mesotropical watercourses, in arenosols and fluvisols, as is characteristic of riverside vegetation.

To the left of the ordinates, we found the greatest ecological diversity, with species ranging from mesotropical to cryorotropical bioclimates. Those closest to the negative part of the ordinate axis are of semi-arid ombrotype and are associated with andosols with poorly consolidated soils due to their proximity to volcanic cones. These include Aphyllocladus denticulatus (21), Diplostephium meyenii (33,34), Gochnatia arequipensis (44,46), Senecio neoviscosus (116), and S. yurensis (123). Among these species, we find both mesotropical and supratropical species, the latter corresponding to localities, that having a typical altitude of the mesotropical belt, are subject to thermal inversion, as is the case with 46 (2400 m, Gochnatia arequipensis) and 116 (2800 m, Senecio neoviscosus), located to the South-East of the city of Arequipa.

On the other hand, the species located on the negative side of the x-axis next to the ordinates combine the features of being located in andosols and cambisols, the proximity to volcanoes, and a lower rainfall. For example, Gochnatia arequipensis (47) was found on andosols and cambisols, 1 km from the volcanic cones of Chachani and under a dry mesotropical bioclimate; Senecio yurensis (129) was found under a semi-arid mesotropical bioclimate, but only 13 km from Pichu-Pichu and with similar edaphological characteristics. The leftmost species, Aristeguietia cursonii (27), Diplostephium meyenii (39) and Mutisia arequipensis (74,75) are in humid orotropical localities with deep soils; however, 27 and 74 are already above the x-axis, showing the importance of washed soils (Luvisols) due to increased rainfall.

In the upper left quadrant, the species Diplostephium meyenii (40) and Gochnatia arequipensis (53) from semi-arid mesotropical localities are prominent. In the first case, it is a mesotropical location at 3100 m a.s.l., an altitude that should correspond to the limit of the supratropical belt. In addition, 53 belongs to a point located on Phaeozems deep soils, and in more humid environments. The rest of the localities in this quadrant belong to the more humid areas in the interior of the territory studied, including species such as Aphyllocladus denticulatus (24,25), Lophopappus cuneatus (66), L. foliosus (68,69), Mutisia arequipensis (72,73,76), and M. orbignyana (81), which grow forming shrublands on Kastanozems or Phaeozems soils. Localities 24, 25 and 72 are from La Unión province; 24 has a cryorotropical thermotype only at 3659 m a.s.l., and 25 and 72 are orotropical at 3300 and 3600 m a.s.l. respectively, which seems to indicate a preferential exposure to southerly winds.

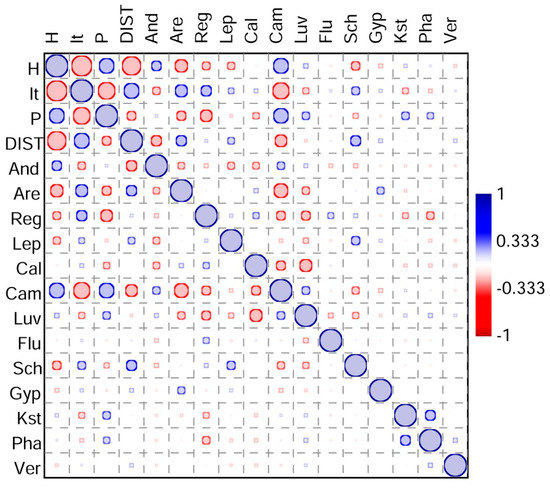

Supporting the PCA results, the correlation matrix (Figure 4) shows the correlation between the different PCA variables, between positive values if there is at least some correlation, or negative values if the correlation is negative. H (altitude) and DIST (distance to volcanoes) are negatively correlated, since at lower altitudes in the coastal desert, the distance to volcanoes is greater. However, P (precipitation) has a positive correlation with altitude because the highest precipitation values are at high altitudes in the Arequipa Region. Similarly, Are (Arenosols) have a negative correlation with altitude and precipitation, as most of the arenosols are on the coast. Kst (Kastanozems) and Pha (Phaeozems) have a positive correlation with precipitation as they are located in the most humid localities of the Andes. Andosols have a positive correlation with altitude as they are mainly found in the vicinity of volcanic cones, which are areas of higher bioclimatic levels, where the value of the thermicity index (It) is lower.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of variables included in the PCA according to Pearson’s parametric test. The blue spectrum means positive correlations, while the red one means negative correlations.

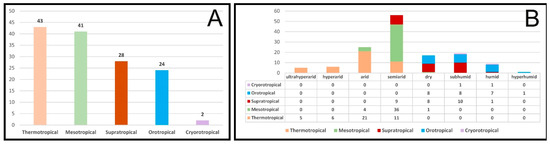

Most of the collections of endemic and semi-endemic species are in the thermotropical bioclimatic zone, that is, on the coast (Figure 5A). These species are: Ambrosia dentata, Heiseria irmscheriana, Helogyne hutchinsonii, Lomanthus icaensis, L. mollendoensis, Ophryosporus bipinnatifidus, Polyachyrus annuus, Senecio smithianus, and Wedelia hoffmanniana. However, the mesotropical belt also has a high number, which includes all the areas of the Arequipa Region between 2100 and 3100 m a.s.l. Here we find Ambrosia pannosa, Aldama dilloniorum, Aphyllocladus denticulatus, Diplostephium meyenii, Gochnatia arequipensis, Helogyne apaloidea, Lophopappus cuneatus, Ophryosporus hoppii, Pluchea absinthioides, Senecio calcicola, and S. yurensis. At the supratropical level, endemisms and semi-endemisms begin to decline, until only two collections extend to the cryorotropical belt. In the supratropical, we can find Aldama dilloniorum, Aristeguietia cursonii, Diplostephium meyenii, Gochnatia arequipensis, Lophopappus foliosus, Mutisia arequipensis, M. orbignyana, Paquirea lanceolata, Senecio neoviscosus, S. scorzonerifolius, and S. yurensis; in the orotropical Aphyllocladus denticulatus, Aristeguietia cursonii, Diplostephium meyenii, Lophopappus cuneatus, L. foliosus, Mutisia arequipensis, Mutisia orbignyana, Onoseris minima, Senecio crassilodix, S. yurensis and Werneria esquilachensis; and finally, in the cryorotropical, Aphyllocladus denticulatus and Diplostephium meyenii. The localities of the thermotropical belt are distributed among the ultrahyperarid to semiarid ombrotypes, an ombrotype that also reaches a higher proportion in the mesotropical belt. From dry to hyperhumid are supra, oro, and cryorotropical localities, many of them located in the interior valleys of the region, indicating that the Andean western slopes are much drier (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Distribution of localities with endemic and semi-endemic Asteraceae in the Arequipa Region among.bioclimatic belts (A) and ombrotypes (B).

The number of times that a species is found within a bioclimatic belt indicates whether or not it is a bioindicator (Figure 6). In contrast to species such as Ambrosia pannosa (mesotropical), Heiseria irmscheriana (thermotropical), Helogyne hutchisonii (thermotropical), Lomanthus mollendoensis (thermotropical), Paquirea lanceolata (supratropical) or Senecio smithianus (thermotropical), there are others with a wider dispersion, such as Senecio yurensis (from thermo- to orotropical), Diplostephium meyenii (from meso- to cryorotropical) or Gochnatia arequipensis (from thermo- to supratropical). Thermotropical bioindicators are Ambrosia dentata, Heiseria irmscheriana, Helogyne hutchisonii, Lomanthus icaensis, L. mollendoensis, L. okopanus, Ophryosporus bipinnatifidus, Polyachyrus annuus, Senecio smithianus, and Wedelia hoffmanniana; however, only one mesotropical bioindicator, Ambrosia pannosa, was found. The supratropical ones are Paquirea lanceolata, Senecio neoviscosus, and S. scorzonerifolius. On the orotropical belt only Onoseris minima, Senecio crassilodix and Werneria esquilachensis are bioindicators. There are no bioindicators on the cryorotropical belt among the endemisms and semi-endemisms of the Arequipa Region.

Figure 6.

Distribution of the endemisms and semi-endemisms of Asteraceae of the Arequipa Region on the bioclimatic belts. Those on a single bioclimatic belt are bioindicators.

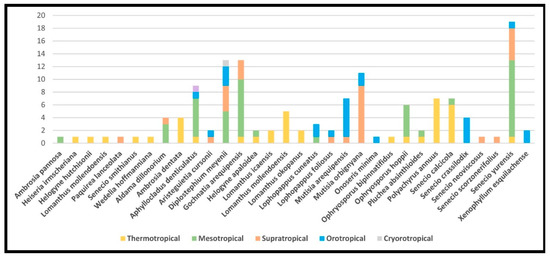

Figure 7A shows the soil groups by locality of collection. From this, we can deduce that there are two main distribution poles for Asteraceae endemisms and semi-endemisms, on saline or gypsiferous basic soils and sandy soils, and on andosols and cambisols. The first group of soils belongs mainly to the thermotropical soil type, while the second group of soils presents localities from thermotropical to cryorotropical, indicating a great extension of the andosols and their influence on the flora (see quadrants and eigenvectors in Figure 3).

Figure 7.

(A) Distribution of Asteraceae collections among the different soil groups according to the quadrants marked by the axes in Figure 3 (Ver: Vertisols, Gyp: Gypsisols, Sch: Solonchaks, Are: Arenosols, Lep: Leptosols, Flu: Fluvisols, Cal: Calcisols, Reg: Regosols, And: Andosols, Cam: Cambisols, Kst: Kastanozems, Pha: Phaeozems, Luv: Luvisols). (B) Proximity of collections of endemisms and semi-endemisms from the volcanoes of Arequipa and northwest Moquegua (MI: Misti, CE: Cerro Nicholson, SAR: Sara-Sara, AND: Andahua-Orcopampa, CHA: Chachani, HUA: Huambo, AYN: Huaynaputina, UBI: Ubinas, AUQ: Cerro Auquihuato, COR: Coropuna, FIR: Nevados Firura, PIC: Pichu-Pichu, SAB: Sabancaya, SOL: Solimana, HRC: Huarancante.

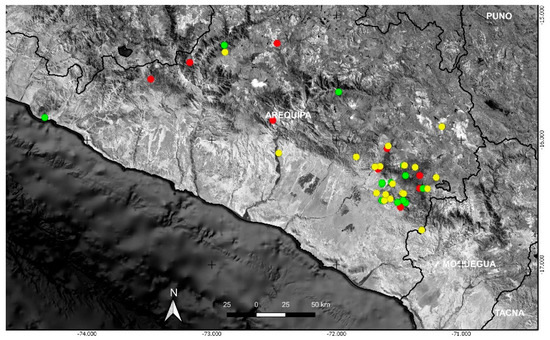

If we analyze the number of Asteraceae endemisms and semi-endemisms found closest to the volcanoes of Arequipa (Figure 7B), we can observe that the greatest number of these are in the space between the Misti, Chachani and Pichu- Pichu volcanoes, in the vicinity of the city of Arequipa, perhaps originating from the influence of a large volcanic complex dated to at least the Eocene (56–37 m.y. ago). Materials from the other volcanoes continued to have an influence, but to a lesser extent. The species most closely linked to this volcanic environment spread over 50 localities are (Figure 8, Appendix A, Table A1; Supplementary Table S3): Aldama dilloniorum, Aphyllocladus denticulatus, Diplostephium meyenii, Gochnatia arequipensis, Lophopappus cuneatus, Mutisia orbignyana, Onoseris minima, Ophryosporus hoppii, Pluchea absinthioides, Senecio crassilodix, S. neoviscosus, S. yurensis, and Werneria esquilachensis.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Diplostephium meyenii (red dots), Gochnatia arequipensis (green dots), and Senecio yurensis (yellow dots) in Arequipa Region.

For Aldama dilloniorum, Onoseris minima, Senecio neoviscosus, and Werneria esquilachensis this volcanic arc signifies a biogeographic barrier to the north (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Distribution of Aldama dilloniorum (yellow dots), Onoseris minima (red dots), Senecio neoviscosus (light blue dots), and Werneria esquilachensis (green dots) in the surroundings of the Chachani, Misti, and Pichu-Pichu volcanoes, including localities from Moquegua.

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity

Arequipa features 232 species of Asteraceae; 49 are endemic to the Peruvian territory, of which only 7 belong to the Arequipa Region. This means that the number of species in Peru decreases from north to south. La Libertad presents 456 species in its flora (135 national endemics, and an unknown number of regional endemics), Ancash 393 (164 national and 13 regional endemics), Lima 344 (120 national and 14 regional endemics), and Ica 72 (11 national and 1 regional endemics). The Ica Region contains very few species due to its small Andean area [49,50,51,52].

4.2. Distribution Patterns

Asteraceae species in Arequipa follow a distribution pattern linked to the climatic characteristics of the territory, soils, and volcanism. Thus, most of the species are found in the lower bioclimatic levels, between the thermotropical and mesotropical (Figure 3 and Figure 5), although some, such as Diplostephium meyenii or Senecio yurensis, extend as far as the orotropical and cryorotropical belts (Figure 8), probably due to their anemochore dispersal. Thus, we also find fewer endemics in the orotropical and cryorotropical levels, which means in the alpine zones, in accordance with the dispersal pattern of the family [53,54]. In other areas of the world, this fact is also recognized [35]; therefore, on the volcanic island of Tenerife (Canary Islands) there are also a large number of endemics living between the inframediterranean and mesomediterranean belts. However, in the territory studied, several Asteraceae species have a narrower distribution, taking into account that there is also a fairly clear separation between the species of the coastal desert and those of the Andean Mountain Range, and that in this desert, most of the endemisms are located in islands of vegetation in the high areas that receive rainfall (‘lomas’) [55].

This bioclimatic distribution is also paralleled by soil types; as saline and gypsiferous soils and arenosols are more prevalent in the hyperarid and ultrahyperarid thermotropical bioclimate of the coastal desert, other soil types are more linked to volcanic eruptions in the rest of Arequipa [33,56], with andosols noticeable when volcanic eruptions are more modern [46], especially at higher altitudes and lower It. In contrast, regosols and leptosols, which are stony and have a negative correlation with altitude and precipitation, arose from older volcanic eruptions (Figure 3).

Ancient volcanism was involved in the speciation of Asteraceae and their distribution [57,58]), as well as the aridity that began to originate in the Palaeocene (66–56 m.y. ago) in the western Andes [59], augmented by the strengthening of the Humboldt Current during the Eocene (56–37 m.y. ago) [60]. In this way, Villaseñor [57] concludes that volcanism created a large number of microhabitats suitable for the diversification of Asteraceae genera. However, modern eruptions have led to a decrease in biodiversity in the orotropical and cryorotropical zones, so that the number of endemic orotropical and cryorotropical bioindicators of Asteraceae in Arequipa is very low. This fact has been confirmed in several studies in other parts of the world, such as Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) [61], the Santorini archipelago (Greece) [32], Chile [62], and Argentinean Patagonia [34]. On the contrary, in non-volcanic territories, as is the case in the Sierra de Guadarrama in the Central System of the Iberian Peninsula, the oromediterranean and cryoromediterranean belts host at least 19 endemisms in a small territorial extension [63]. Related to this final observation, the Lima Region, with similar precipitation (humid and hyperhumid ombrotypes), and which has no modern volcanoes, has 21 oro-cryorotropical endemisms of Asteraceae [64], while the Arequipa Region has only 3.

Maps (Figure 8 and Figure 9) indicate a higher concentration of Asteraceae endemics and semi-endemics in the vicinity of the city of Arequipa. Brecheisen et al. [65] mapped the agricultural and urban expansion of the city in 1966, 1978, and 2019, which has begun to occupy part of the slopes of Chachani, Misti and Pichu-Pichu, endangering many of the populations studied through elimination and alteration. Therefore, we propose the creation of flora micro-reserves to help their conservation, inspired by models and legislation established in other countries [66].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d15010033/s1, Table S1: 2206 herbarium sheets studied from Arequipa Region, with localities, collectors and coordinates; Table S2: Astereceae of Arequipa with the distribution in Peruvian regions, a representative herbarium sheet, life form, and altitudinal range; Table S3: Table with the values taken to obtain the PCA of Figure 2, bioclimatic diagnosis, volcanoes closest to the localities studied, and percentage of soil types per pixel of SoilGrids database in a locality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B. and A.G.-d.-M.; methodology, H.B., E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; software, E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; validation, E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; formal analysis, E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; investigation, H.B., E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; resources, E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; data curation, H.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.-d.-M.; writing—review and editing, H.B., E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; visualization, H.B., E.L.-P. and A.G.-d.-M.; supervision, H.B. and A.G.-d.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We extend gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and to the editor for their help in improving our paper. We also extend gratitude to Brian Crilly for his editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Table with the values taken to obtain the PCA of Figure 2, bioclimatic diagnosis, volcanoes closest to the localities studied, and percentage of soil types per pixel of SoilGrids database in a locality (Synthesis of the Supplementary Table S3).

Table A1.

Table with the values taken to obtain the PCA of Figure 2, bioclimatic diagnosis, volcanoes closest to the localities studied, and percentage of soil types per pixel of SoilGrids database in a locality (Synthesis of the Supplementary Table S3).

| Locality Number | Locality of Table S1 | Endemisms and Semi-Endemisms of Arequipa Region | Regional Distribution in Peru | Locality of Arequipa Region | Bioclimatic Diagnosis | H | It | P | DIST | And | Are | Reg | Lep | Cal | Cam | Luv | Flu | Sch | Gyp | Kst | Pha | Ver | Volcano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | Ambrosia pannosa | AR | Tingo | Mes sem | 2224 | 428 | 134 | 12.72 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 14 | 19 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 2 | 79 | Heiseria irmscheriana | AR | Mejia | The ulha | 30 | 641 | 3 | 81.03 | 0 | 11 | 19 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 3 | 82 | Helogyne hutchisonii | AR | Atico | The ha | 57 | 511 | 19 | 92.56 | 0 | 30 | 21 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 4 | 101 | Lomanthus mollendoensis | AR | Atiquipa | The sem | 500 | 532 | 111 | 98.05 | 0 | 8 | 15 | 20 | 0 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 5 | 130 | Paquirea lanceolata | AR | Orcopampa | Sup suh | 3790 | 193 | 600 | 14.32 | 6 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Andahua-Orcopampa |

| 6 | 182 | Senecio smithianus | AR | Atiquipa | The sem | 275 | 530 | 111 | 106.16 | 0 | 11 | 19 | 20 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 7 | 214 | Wedelia hoffmanniana | AR | Mejia | The ulha | 444 | 552 | 0 | 138.48 | 0 | 11 | 20 | 16 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 8 | 524 | Aldama dilloniorum | AR MO TA | Cerro Verde | Mes sem | 2600 | 438 | 116 | 20 | 0 | 9 | 26 | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 9 | 525 | Idem | AR MO TA | Yura | Mes sem | 3100 | 346 | 188 | 8.17 | 17 | 0 | 21 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 10 | 526 | Idem | AR MO TA | Chachani | Mes sem | 2800 | 374 | 134 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 14 | 12 | 0 | 22 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 11 | 527 | Idem | AR MO TA | Ojuli | Sup sem | 2500 | 243 | 179 | 7.38 | 0 | 10 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 12 | 1092 | Ambrosia dentata | AR IC | Jahuay | The ulha | 300 | 503 | 0 | 146.61 | 0 | 11 | 23 | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 13 | 1094 | Idem | AR IC | Atico | The ha | 277 | 517 | 19 | 91.82 | 0 | 25 | 18 | 27 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 14 | 1100 | Idem | AR IC | Chala | The sem | 430 | 531 | 114 | 88.98 | 0 | 15 | 22 | 15 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 15 | 1101 | Idem | AR IC | Los Cerrillos | The ulha | 800 | 532 | 0 | 149.12 | 0 | 13 | 17 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 16 | 1103 | Idem | AR IC | Atiquipa | The ar | 500 | 530 | 97 | 102.27 | 0 | 11 | 16 | 22 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 17 | 19 | Aphyllocladus denticulatus | AR MO TA | Huancarqui | Mes ar | 2600 | 417 | 37 | 27.19 | 0 | 10 | 16 | 18 | 11 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 18 | 653 | Idem | AR MO TA | Polobaya | Mes sem | 2900 | 407 | 122 | 47.57 | 0 | 8 | 27 | 9 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huaynaputina |

| 19 | 654 | Idem | AR MO TA | Quebrada Escalerilla | Mes ar | 2754 | 247 | 76 | 13.9 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 23 | 11 | 16 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ubinas |

| 20 | 655 | Idem | AR MO TA | Socabaya | Mes sem | 2160 | 475 | 141 | 13.21 | 0 | 10 | 24 | 16 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 21 | 656 | Idem | AR MO TA | Yura | Mes sem | 2200 | 426 | 188 | 11.89 | 16 | 8 | 21 | 13 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 22 | 1177 | Idem | AR MO TA | Atico | The ha | 1274 | 521 | 19 | 91.27 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 28 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 23 | 1178 | Idem | AR MO TA | Quicacha | Mes sem | 2673 | 433 | 226 | 36.98 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 21 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 24 | 1716 | Idem | AR MO TA | Puyca | Cry hum | 3659 | 42 | 1009 | 53.62 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 16 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 10 | 0 | Cerro Auquihuato |

| 25 | 1717 | Idem | AR MO TA | Pampamarca | Oro hum | 3300 | 138 | 993 | 31.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 21 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 14 | 0 | Cerro Auquihuato |

| 26 | 1488 | Aristeguietia cursonii | AR MO TA | Salamanca | Sup hum | 3600 | 297 | 1001 | 11.29 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 27 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 27 | 21 | Idem | AR MO TA | Cotahuasi | Oro hhum | 4200 | 90 | 1603 | 14.99 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 22 | 4 | 25 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nevados Firura |

| 28 | 321 | Diplostephium meyenii | AR AY MO TA | Arequipa | Mes sem | 2363 | 471 | 141 | 16 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 29 | 324 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chiguata | Oro dry | 4000 | 85 | 324 | 2.75 | 12 | 0 | 15 | 11 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 30 | 330 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Misti | Sup dry | 3640 | 235 | 324 | 2.15 | 14 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 23 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 31 | 332 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chachani | Oro dry | 4000 | 72 | 329 | 2.27 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 14 | 0 | 20 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 32 | 337 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Pampa de Arrieros | Sup dry | 3700 | 209 | 442 | 14.49 | 13 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 26 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 33 | 338 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Rio de Lomas | Sup sem | 2850 | 192 | 179 | 6.16 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 20 | 13 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 34 | 339 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Yura | Mes sem | 2700 | 383 | 234 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 16 | 18 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 35 | 341 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Yura, Chingana | Mes sem | 3000 | 337 | 134 | 7 | 21 | 0 | 12 | 13 | 0 | 10 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 36 | 1017 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Cahuacho | Sup dry | 3380 | 316 | 381 | 12.54 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 37 | 1477 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Condesuyos | Cry shu | 4300 | 44 | 733 | 11.43 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 26 | 6 | 27 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nevados Firura |

| 38 | 1478 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chuqui-bamba | Mes ar | 2300 | 404 | 45 | 21.23 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 24 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 39 | 1688 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Tauría | Oro hum | 4000 | 144 | 926 | 26.46 | 14 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 0 | 28 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 40 | 57 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Polobaya-Pocsi | Mes sem | 3100 | 352 | 202 | 19.78 | 15 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 41 | 659 | Gochnatia arequipensis | AR AY MO TA | Arequipa | Mes sem | 2755 | 398 | 122 | 17.67 | 9 | 10 | 22 | 21 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 42 | 662 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Arequipa, aeropuerto | Mes sem | 2600 | 426 | 134 | 13.74 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 15 | 19 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 43 | 663 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Cerro Verde | Mes sem | 2600 | 432 | 116 | 26.99 | 0 | 10 | 24 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 44 | 665 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chiguata | Mes sem | 3000 | 370 | 251 | 3.29 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 45 | 668 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Misti | Sup dry | 3624 | 235 | 324 | 2.6 | 11 | 0 | 12 | 13 | 0 | 21 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 46 | 669 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Mollebaya | Sup sem | 2400 | 245 | 141 | 11.61 | 8 | 17 | 21 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 47 | 670 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chachani | Mes dry | 3050 | 342 | 329 | 5.16 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 19 | 0 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 48 | 672 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Quebrada Lajas | Mes sem | 2300 | 462 | 152 | 12.41 | 0 | 6 | 31 | 16 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 49 | 673 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Socabaya | Mes sem | 2344 | 460 | 141 | 22.04 | 0 | 9 | 18 | 16 | 19 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 50 | 674 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Queque | Mes sem | 2300 | 459 | 166 | 14.7 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 18 | 18 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 51 | 1179 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Atiquipa | The sem | 350 | 551 | 105 | 103.76 | 0 | 13 | 15 | 21 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 52 | 1389 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Cabanaconde | Sup dry | 3200 | 306 | 496 | 19.92 | 8 | 0 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sabancaya |

| 53 | 1718 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Cotahuasi | Mes sem | 2700 | 341 | 144 | 26.64 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 17 | 0 | 23 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | Nevados Firura |

| 54 | 1057 | Helogyne apaloidea | AR MO | Caravelí | Mes sem | 2626 | 490 | 207 | 37.93 | 0 | 8 | 27 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 55 | 1058 | Idem | AR MO | Atico | The ha | 50 | 590 | 19 | 87.64 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 30 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 56 | 99 | Lomanthus icaensis | AR IC | Acarí | The ar | 650 | 535 | 37 | 126.44 | 0 | 16 | 18 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 57 | 1244 | Idem | AR IC | Los Cerrillos | The ar | 865 | 532 | 85 | 143.65 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 15 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 58 | 1254 | Lomanthus mollendoensis | AR | Toro | The sem | 350 | 557 | 109 | 103.56 | 0 | 10 | 23 | 21 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 59 | 1255 | Idem | AR | Atiquipa | The sem | 200 | 532 | 110 | 104.11 | 0 | 11 | 16 | 22 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 60 | 1662 | Idem | AR | Islay | The ulha | 10 | 490 | 3 | 80.48 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 61 | 1664 | Idem | AR | Rio Tambo | The ar | 680 | 578 | 50 | 94.07 | 0 | 27 | 12 | 29 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huaynaputina |

| 62 | 1666 | Idem | AR | Mollendo | The ar | 928 | 517 | 62 | 73.44 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 33 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 63 | 102 | Lomanthus okopanus | AR IC | Lomas de Cháparra | The sem | 500 | 611 | 143 | 76.15 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 21 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 10 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 64 | 1258 | Idem | AR IC | Lomas de Ocopa | The sem | 700 | 532 | 110 | 100.12 | 0 | 11 | 19 | 20 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 65 | 105 | Lophopappus cuneatus | AR TA | Arequipa | Mes sem | 2447 | 386 | 123 | 22.19 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 66 | 1393 | Idem | AR TA | Caylloma | Oro suh | 3200 | 119 | 750 | 25.41 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Sabancaya |

| 67 | 1499 | Idem | AR TA | Chuqui-bamba | Oro suh | 3900 | 160 | 706 | 15.21 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 68 | 1394 | Lophopappus foliosus | AR MO | Cabanaconde | Sup suh | 3700 | 232 | 693 | 12.95 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | Sabancaya |

| 69 | 106 | Idem | AR MO | Chivay | Oro suh | 4000 | 83 | 688 | 36.74 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 14 | 0 | 25 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | Sabancaya |

| 70 | 1401 | Mutisia arequipensis | AR AY | Caylloma | Oro suh | 3200 | 119 | 750 | 25.28 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 19 | 23 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sabancaya |

| 71 | 1727 | Idem | AR AY | Cotahuasi | Oro hum | 4284 | 72 | 1202 | 10.8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 24 | 5 | 26 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nevados Firura |

| 72 | 1728 | Idem | AR AY | Puyca | Oro hum | 3600 | 82 | 1030 | 13.54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 17 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 10 | 0 | Nevados Firura |

| 73 | 1730 | Idem | AR AY | Huaynacotas | Oro hum | 3931 | 144 | 1238 | 20.89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 23 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | Nevados Firura |

| 74 | 1731 | Idem | AR AY | Tauría | Oro hum | 4200 | 110 | 1434 | 22.71 | 7 | 0 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 36 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Solimana |

| 75 | 1732 | Idem | AR AY | Toro | Oro hum | 4400 | 61 | 1487 | 3.67 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 17 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Solimana |

| 76 | 1770 | Idem | AR AY | Sayla | Sup suh | 3600 | 238 | 755 | 19.63 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 25 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 77 | 706 | Mutisia orbignyana | AR MO TA | Arequipa | Sup sem | 3156 | 312 | 264 | 1.9 | 16 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 78 | 709 | Idem | AR MO TA | Arequipa-Cusco | Sup sem | 3375 | 264 | 261 | 13.15 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 15 | 11 | 20 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 79 | 1299 | Idem | AR MO TA | Pampacolca | Oro suh | 3900 | 148 | 600 | 6.82 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 11 | 0 | 26 | 15 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 80 | 1300 | Idem | AR MO TA | Andahua | Sup suh | 3611 | 238 | 668 | 8.6 | 11 | 0 | 9 | 15 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Andahua-Orcopampa |

| 81 | 1303 | Idem | AR MO TA | Castilla | Sup suh | 3600 | 170 | 754 | 29.38 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 17 | 0 | 24 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Andahua-Orcopampa |

| 82 | 1402 | Idem | AR MO TA | Chivay | Oro suh | 4400 | 104 | 574 | 34.14 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 27 | 0 | 18 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sabancaya |

| 83 | 1403 | Idem | AR MO TA | Puquina | Sup suh | 3600 | 286 | 575 | 20.91 | 11 | 0 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 16 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 84 | 1404 | Idem | AR MO TA | Caylloma | Sup suh | 3639 | 214 | 574 | 30.08 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 19 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | Sabancaya |

| 85 | 1406 | Idem | AR MO TA | Cabanaconde | Sup suh | 3700 | 199 | 754 | 15.55 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 26 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 86 | 1407 | Idem | AR MO TA | Huambo | Sup suh | 3800 | 187 | 600 | 1.1 | 9 | 0 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 34 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 87 | 1502 | Idem | AR MO TA | Condesuyos | Sup suh | 3800 | 178 | 533 | 13.82 | 12 | 0 | 19 | 8 | 0 | 16 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 88 | 122 | Onoseris minima | AR MO | Arequipa | Oro dry | 4436 | 89 | 352 | 0.83 | 7 | 0 | 16 | 17 | 0 | 27 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 89 | 124 | Ophryosporus bipinnatifidus | AR MO | Cachendo | The ar | 400 | 597 | 48 | 110.8 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | Huaynaputina |

| 90 | 126 | Ophryosporus hoppii | AR MO TA | Atiquipa | The sem | 300 | 502 | 113 | 105.23 | 0 | 10 | 19 | 21 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sara-Sara |

| 91 | 459 | Idem | AR MO TA | Arequipa | Mes sem | 2700 | 398 | 122 | 2.53 | 11 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 31 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 92 | 958 | Idem | AR MO TA | Camaná | The ar | 600 | 611 | 44 | 106.59 | 0 | 15 | 10 | 29 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 93 | 960 | Idem | AR MO TA | Ocoña | The ar | 205 | 589 | 52 | 90.61 | 0 | 15 | 25 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 94 | 1287 | Idem | AR MO TA | Aplao | The ar | 657 | 522 | 50 | 46.47 | 0 | 12 | 20 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 95 | 1552 | Idem | AR MO TA | Mollendo | The ha | 230 | 507 | 26 | 69.17 | 0 | 22 | 16 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 96 | 142 | Pluchea absinthioides | AR | Arequipa | Mes sem | 2287 | 476 | 148 | 14.86 | 8 | 0 | 22 | 20 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 97 | 745 | Idem | AR | Tiabaya | The sem | 2100 | 504 | 110 | 15.87 | 0 | 35 | 23 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | Misti |

| 98 | 144 | Polyachyrus annuus | AR IC MO TA | Atico | The ar | 50 | 630 | 50 | 106.39 | 0 | 22 | 20 | 26 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Coropuna |

| 99 | 991 | Idem | AR IC MO TA | Mollendo | The ar | 650 | 534 | 47 | 63.67 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 100 | 992 | Idem | AR IC MO TA | Camaná | The ar | 300 | 611 | 44 | 96.2 | 0 | 15 | 10 | 29 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 101 | 994 | Idem | AR IC MO TA | Arantas | The ar | 680 | 614 | 47 | 81.38 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 29 | 0 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 102 | 1214 | Idem | AR IC MO TA | Chala | The sem | 50 | 541 | 143 | 88.11 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | Sara-Sara |

| 103 | 1645 | Idem | AR IC MO TA | Mejía | The ar | 200 | 576 | 46 | 89.48 | 0 | 18 | 11 | 31 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 104 | 1649 | Idem | AR IC MO TA | Islay | The ar | 181 | 594 | 47 | 78.22 | 0 | 15 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 105 | 806 | Senecio calcicola | AR IC | Chucarapi | The ar | 750 | 578 | 53 | 104.47 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 26 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huaynaputina |

| 106 | 807 | Idem | AR IC | Quebrada Guerreros | Mes sem | 2766 | 372 | 116 | 22.05 | 0 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 107 | 1004 | Idem | AR IC | Arantas | The ar | 980 | 534 | 47 | 81.92 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 28 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 108 | 1668 | Idem | AR IC | Mollendo | The ar | 560 | 526 | 53 | 77.98 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 109 | 1673 | Idem | AR IC | Islay | The ar | 17 | 597 | 48 | 108.79 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | Huaynaputina |

| 110 | 1675 | Idem | AR IC | Islay | The ar | 250 | 596 | 55 | 78.58 | 0 | 15 | 11 | 35 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 111 | 1676 | Idem | AR IC | Tintayami | The ar | 700 | 566 | 51 | 76.69 | 0 | 24 | 12 | 24 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 112 | 808 | Senecio crassilodix | AR AY MO TA | Arequipa | Oro dry | 4200 | 110 | 407 | 27.11 | 9 | 0 | 14 | 21 | 6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 113 | 809 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chiguata | Oro dry | 4321 | 94 | 408 | 24.7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 13 | 22 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ubinas |

| 114 | 810 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Chachani | Oro dry | 4200 | 72 | 320 | 2.51 | 10 | 0 | 14 | 12 | 0 | 22 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 115 | 164 | Idem | AR AY MO TA | Orcopampa | Oro suh | 4200 | 97 | 619 | 16.05 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | Andahua-Orcopampa |

| 116 | 174 | Senecio neoviscosus | AR MO | Baños de Jesús | Sup sem | 2800 | 241 | 207 | 6.99 | 7 | 0 | 23 | 16 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 117 | 180 | Senecioscorzonerifolius | AR MO TA | Arequipa-Cusco | Sup sem | 3850 | 268 | 236 | 14.53 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 118 | 187 | Senecio yurensis | AR MO | Baños de Jesús | Sup sem | 2700 | 244 | 187 | 9.4 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 119 | 912 | Idem | AR MO | Arequipa | Sup sem | 3800 | 229 | 196 | 6.46 | 11 | 0 | 16 | 18 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 120 | 914 | Idem | AR MO | Arequipa, aeropuerto | Mes sem | 2900 | 423 | 204 | 11.14 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 14 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 121 | 919 | Idem | AR MO | Cerro San Ignacio | Mes sem | 2500 | 431 | 117 | 17.59 | 0 | 9 | 25 | 24 | 16 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 122 | 920 | Idem | AR MO | Cerro Verde | Mes sem | 2600 | 446 | 107 | 25.05 | 0 | 10 | 27 | 16 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 123 | 922 | Idem | AR MO | Chiguata | Mes sem | 2100 | 370 | 264 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 16 | 6 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 124 | 926 | Idem | AR MO | Chili | Mes sem | 2500 | 450 | 103 | 18.43 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 14 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 125 | 927 | Idem | AR MO | Lluta | Sup dry | 3884 | 261 | 518 | 10.12 | 7 | 0 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 26 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 126 | 928 | Idem | AR MO | Misti | Sup dry | 3831 | 190 | 398 | 8.77 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 19 | 0 | 20 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 127 | 929 | Idem | AR MO | Chachani | Sup dry | 3600 | 277 | 320 | 2.45 | 10 | 0 | 19 | 17 | 0 | 20 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 128 | 931 | Idem | AR MO | Polobaya-Chapi | Mes ar | 2540 | 456 | 100 | 42.31 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 14 | 23 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huaynaputina |

| 129 | 932 | Idem | AR MO | Quebrada Honda | Mes sem | 2600 | 471 | 122 | 13.63 | 10 | 0 | 14 | 15 | 0 | 27 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 130 | 933 | Idem | AR MO | Tiabaya | Mes sem | 2430 | 444 | 110 | 21.31 | 0 | 29 | 23 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Misti |

| 131 | 936 | Idem | AR MO | Yura | Mes sem | 2985 | 346 | 273 | 7.92 | 19 | 0 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 132 | 945 | Idem | AR MO | Yura-Huanca | Mes sem | 2700 | 418 | 236 | 16.42 | 0 | 7 | 18 | 17 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cerro Nicholson |

| 133 | 946 | Idem | AR MO | Yura-Huanca | Mes sem | 2500 | 409 | 280 | 10.61 | 0 | 8 | 28 | 18 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chachani |

| 134 | 1005 | Idem | AR MO | Tambillo | The ha | 1199 | 542 | 26 | 71.35 | 0 | 10 | 19 | 19 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huambo |

| 135 | 1459 | Idem | AR MO | San Antonio de Chuca | Oro suh | 4442 | 60 | 657 | 37.26 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 19 | 17 | 29 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Huarancante |

| 136 | 1756 | Idem | AR MO | Cotahuasi | Mes sem | 2600 | 341 | 144 | 10.19 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 16 | 0 | 33 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Solimana |

| 137 | 227 | Werneria esquilachensis | AR MO TA | Pichu-Pichu | Oro dry | 4926 | 142 | 324 | 1.03 | 8 | 0 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 20 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

| 138 | 951 | Idem | AR MO TA | Tunel El Cimbral | Oro dry | 4279 | 82 | 393 | 3.03 | 15 | 0 | 19 | 14 | 6 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pichu-Pichu |

Symbols: AR—Arequipa, AY—Ayacucho, IC—Ica, MO—Moquegua, TA—Tacna. Bioclimatic diagnosis and bioclimatic belts: The—Thermotropical, Mes—Mesotropical, Sup—Supratropical, Oro—Orotropical, Cry—Cryorotropical. Ombrotypes: ulha—Ultrahyperarid, ha—Hyperarid, ar—Arid, sem—Semiarid, dry—Dry, suh—Subhumid, hum—Humid, hhum—Hyperhumid, H—Altitude (m), It—Thermicity Index, P—Annual precipiation (mm). DIST—Smaller distance from the volcanoes (Km). Soil types: And—Andosols, Are—Arenosols, Reg—Regosols, Lep—Leptosols, Cal—Calcisols, Cam—Cambisols, Luv—Luvisols, Flu—Fluvisols, Sch—Solonchaks, Gyp—Gypsisols, Kst—Kastanozems, Pha—Phaeozems, Ver—Vertisols.

References

- Brako, L.; Zarucchi, J.L. Catalogue of the Flowering Plants and Gymnosperms of Peru; Missouri Botanical Garden: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa Ulloa, C.; Acevedo-Rodríguez, P.; Beck, S.; Belgrano, M.J.; Bernal, R.; Berry, P.E.; Brako, L.; Celis, M.; Davidse, G.; Forzza, R.C.; et al. An integrated assessment of the vascular plant species of the Americas. Science 2017, 358, 1614–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, J.; Granda, A.; Beltrán, H. Contributions to the Andean Senecioneae (Compositae) V. Novelties for Peru, new synonyms, and taxonomic notes. Phytotaxa 2019, 424, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.; Granda, A.; Funk, V.A. New combinations and synonyms in discoid caespitose Andean Senecio (Senecioneae, Compositae). PhytoKeys 2019, 132, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weddell, H.A. Chloris Andina. Essai d’Une Flore de la Région Alpine des Cordilléres de l’Amérique du Sud; P. Bertrand Publishing: Paris, France, 1855; Volume I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Supplementum Plantarum; Impensis Orphanotrophei: Brunsvigae, Germany, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.; Pavón, J. Flora Peruvianae et Chilensis Prodromus; Imprenta de Sancha: Madrid, Spain, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Humboldt, A.; Bonpland, A.; Kunth, C.S. Nova Genera et Species Plantarum; Libreriae Graeco-Latino-Germanicae: Lutetiae Parisiorum, France, 1820; Volume IV. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessing, C.F. Synopsis Generum Compositarum; Sentibus Dunckeri et Humelotii: Berlin, Germany, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weberbauer, A. El Mundo Vegetal de los Andes Peruanos; Ministerio de Agricultura: Lima, Perú, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Cuatrecasas, J. Studies on Andean Compositae IV. Brittonia 1960, 12, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, A.L. Revisión del género Mutisia (Compositae). Opera Lilloana 1965, 13, 1–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreyra, R. Flora of Peru. Asteraceae, part VI. Tribe Mutisieae. Fieldiana Bot. 1995, 35, 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A.L. Revisión del género Gochnatia (Compositae). Rev. Mus. Plata 1971, 66, 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M.O.; Luebert, F. Synopsis of Plazia Ruiz & Pav. (Onoserideae, Asteraceae), including a new species from northern Peru. PhytoKeys 2014, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cuatrecasas, J. Senecioneae andinae novae. Collect. Bot. 1953, 3, 261–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A.L. Notas sobre los Senecio sudamericanos VIII. Notas Mus. Eva Perón 1955, 18, 191–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A.L. El género Senecio (Compositae) en Bolivia. Darwiniana 1985, 26, 79–217. [Google Scholar]

- Vision, T.J.; Dillon, M.O. Sinopsis de Senecio, L. (Senecioneae, Asteraceae) para el Perú. Arnaldoa 1996, 4, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, H. Sinopsis del género Werneria (Asteraceae: Senecioneae) del Perú. Arnaldoa 2017, 24, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hind, D.J.N. A new genus, Rockhausenia (Compositae: Senecioneae: Senecioninae). Kew Bull. 2022, 77, 691–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, V.A. Xenophyllum, a new Andean genus extracted from Werneria s.l. (Compositae: Senecioneae). Novon 1997, 7, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, H. Sinopsis del género Xenophyllum (Asteraceae: Senecioneae) del Perú. Arnaldoa 2016, 23, 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- Galán de Mera, A.; Linares Perea, E. La Vegetación de la Región Arequipa (Perú); Universidad Nacional de San Agustín: Arequipa, Perú, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Galán de Mera, A.; Linares Perea, E.; Campos de la Cruz, J.; Vicente Orellana, J.A. Nuevas observaciones sobre la vegetación del Sur del Perú. Del Desierto Pacífico al Altiplano. Acta Bot. Malac. 2009, 34, 107–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilling, R.I. Volcanism and associated hazards: The Andean perspective. Adv. Geosci. 2009, 22, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennan, L. Large-scale geomorphology in the central Andes of Peru and Bolivia: Relation to tectonic, magmatic and climatic processes. In Geomorfology and Global Tectonics; Summerfield, M.A., Ed.; Wiley: London, UK, 2000; pp. 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, S.L.; Francis, P.W. Volcanoes of the Central Andes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thouret, J.C.; Juvigne, E.; Gourgaud, A.; Boivin, P.; D’Avila, J. Reconstruction of the AD 1600 Huaynaputina eruption based on the correlation of geologic evidence with early Spanish chronicles. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2002, 115, 529–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullar, F.M. Volcanoes of Southern Peru. Bull. Volcanol. 1962, 24, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebti, P.P.; Thouret, J.-C.; Wörner, G.; Fornari, M. Neogene and Quaternary ignimbrites in the area of Arequipa, Southern Peru: Stratigraphical and petrological correlations. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2006, 154, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, P.; Raus, T.; Mucina, L.; Tsiripidis, I. Vegetation patterns and primary succesion on sea-born volcanic islands (Santorini archipelago, Aegean Sea, Greece). Phytocoenologia 2010, 40, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, C.; Cáceres Huamaní, F.; Cano, A.; La Torre, M.I.; Weigend, M. 400 years for long-distance dispersal and divergence in the northern Atacama desert—Insights from the Huaynaputina pumice slopes of Moquegua, Peru. J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, L.; Gonzalez, S.; Franzese, J.; Oddi, F. Effect of volcanic ash deposition on the early recovery of gap vegetation in Northwestern Patagonian steppes. J. Arid Environ. 2015, 122, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Osorio, M.E.; Wildpret Martín, W.-H.; González Negrín, R.; Wildpret de la Torre, W. Study of the current vegetation of the historical lava flows of the Arafo Volcano, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. Mediterr. Bot. 2020, 41, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiers, B.M. Index Herbariorum. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Navarro, G.; Penas, A.; Costa, M. Biogeographic Map of South America. A preliminary survey. Int. J. Geobot. Res. 2011, 1, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Geographic Information System. Available online: https://www.qgis.org (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Sánchez-Mata, D.; Costa, M. North American Boreal and Western temperate forest vegetation (Syntaxonomical synopsis of the potential natural plant communities of North America, II). Itinera Geobot. 1999, 12, 5–316. [Google Scholar]

- Galán de Mera, A.; Campos de la Cruz, J.; Linares Perea, E.; Montoya Quino, J.; Torres Marquina, I.; Vicente Orellana, J.A. A phytosociological classification of the Peruvian vegetation. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán de Mera, A.; Linares Perea, E.; Trujillo Vera, C.; Villasante Benavides, F. Termoclima y humedad en el sur del Perú. Bioclimatología y bioindicadores en el departamento de Arequipa. Zonas Áridas 2010, 14, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- METEOBLUE. Available online: https://www.meteoblue.com (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Karger, D.N.; Conrad, O.; Böhner, J.; Kawohl, T.; Kreft, H.; Soria-Auza, R.W.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Linder, H.P.; Kessler, M. Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; Mendes de Jesus, J.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Ruiperez González, M.; Kilibarda, M.; Blagotić, A.; Shangguan, W.; Wright, M.N.; Geng, X.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; et al. SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference for Soils Resources 2006; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Venzke, E. Volcanoes of the World, v. 4.11.2; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Earth. Satellite photograph of Peru. Available online: https://www.google.com/earth (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Hammer, Ø. PAST: Paleontological Statistics; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 1999–2021.

- Rodríguez Rodríguez, E.F.; Alvítez Izquierdo, E.; Pollack Velásquez, L.; Melgarejo Salas, N.; Sagástegui Alva, A. Catálogo de Asteraceae de la Región La Libertad, Perú. Sagasteguiana 2016, 4, 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, H. (Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú); Cano, A. (Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú). Las Asteraceae de la Región Ancash. Personal communication. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, H. Distribución y riqueza de Asteráceas en las cuencas hidrográficas del departamento de Lima, Perú. Arnaldoa 2018, 25, 799–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, O.K.; Orellana-García, A.; Pecho-Quispe, J.O. An Annotated Checklist to Vascular Flora of the Ica Region, Peru—With notes on endemic species, habitat, climate and agrobiodiversity. Phytotaxa 2019, 389, 1–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Muñoz-Schick, M. Classification, diversity, and distribution of Chilean Asteraceae: Implications for biogeography and conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, C.; Melcher, I.; Kusumoto, B.; Cuesta, F.; Cleef, A.; Meneses, R.I.; Halloy, S.; Llambi, L.D.; Beck, S.; Muriel, P.; et al. Plant dispersal strategies of high tropical alpine communities across the Andes. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán de Mera, A.; Vicente Orellana, J.A.; Lucas García, J.A.; Probanza Lobo, A. Phytogeographical sectoring of the Peruvian coast. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 1997, 6, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfiffner, O.A.; González, L. Mesozoic-Cenozoic evolution of the western margin of South America: Case study of the Peruvian Andes. Geosciences 2013, 3, 262–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, J.L. The genera of Asteraceae endemic to Mexico and adjacent regions. Aliso 1990, 12, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoré, M.L.; Stuessy, T.F. The place and time of origin of the Compositae with additional comments on the Clyceraceae and Goodeniaceae. In Advances in Compositae Systematics; Hind, D.J.N., Jeffrey, C., Pope, G.V., Eds.; The Royal Botanic Garden Kew: London, UK, 1995; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardi, S.; Gaviria, M.H.; Estrada, J. La flora del superpáramo venezolano y sus relaciones fitogeográficas a lo largo de los Andes. Plantula 1997, 1, 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Livermore, R.; Nankivell, A.; Eagles, G.; Morris, P. Paleogene opening of Drake Passage. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 236, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemp, A. Vegetation of Kilimanjaro: Hidden endemics and missing bamboo. Afr. J. Ecol. 2006, 44, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, F.J.; Jones, J.A.; Crisafulli, C.M.; Lara, A. Effects of volcanic and hydrologic processes on forest vegetation: Chaitén Volcano, Chile. Andean Geol. 2013, 40, 359–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Fernández-González, F.; Sánchez-Mata, D.; Pizarro, J. Vegetación de la Sierra de Guadarrama. Itinera Geobot. 1990, 4, 3–132. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, H.; Galán de Mera, A. Las Angiospermas del Departamento de Lima (Perú): Diversidad y patrones de distribución. Arnaldoa 2021, 28, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecheisen, Z.; Hamp-Adams, N.; Tomasek, A.; Foster, E.J.; Filley, T.; Villalta Soto, M.; Zuniga Reynoso, L.; De Lima Moraes, A.; Schulze, D.G. Using remote sensing to discover historic context of human-environmental water resource dynamics. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2020, 171, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna Lumbreras, E. The Micro-Reserves as a Tool for Conservation of Threatened Plants in Europe; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).