The First 3 Years: Movements of Reintroduced Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) in Banff National Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Ensuring there was adequate habitat [9];

- (2)

- Starting with young animals to limit their attachment to the source area [19];

- (3)

- Ensuring all females were pregnant and calved shortly after translocation to better anchor to the new area [20];

- (4)

- (5)

- Discouraging dispersals with short (0.2–2 km long), 150 cm high, wildlife friendly bison drift fences consisting of five smooth wires along likely exit routes from the reintroduction zone [26];

- (6)

- Physically hazing bison from boundary areas by foot, horseback or helicopter where drift fences were impractical [27].

- (1)

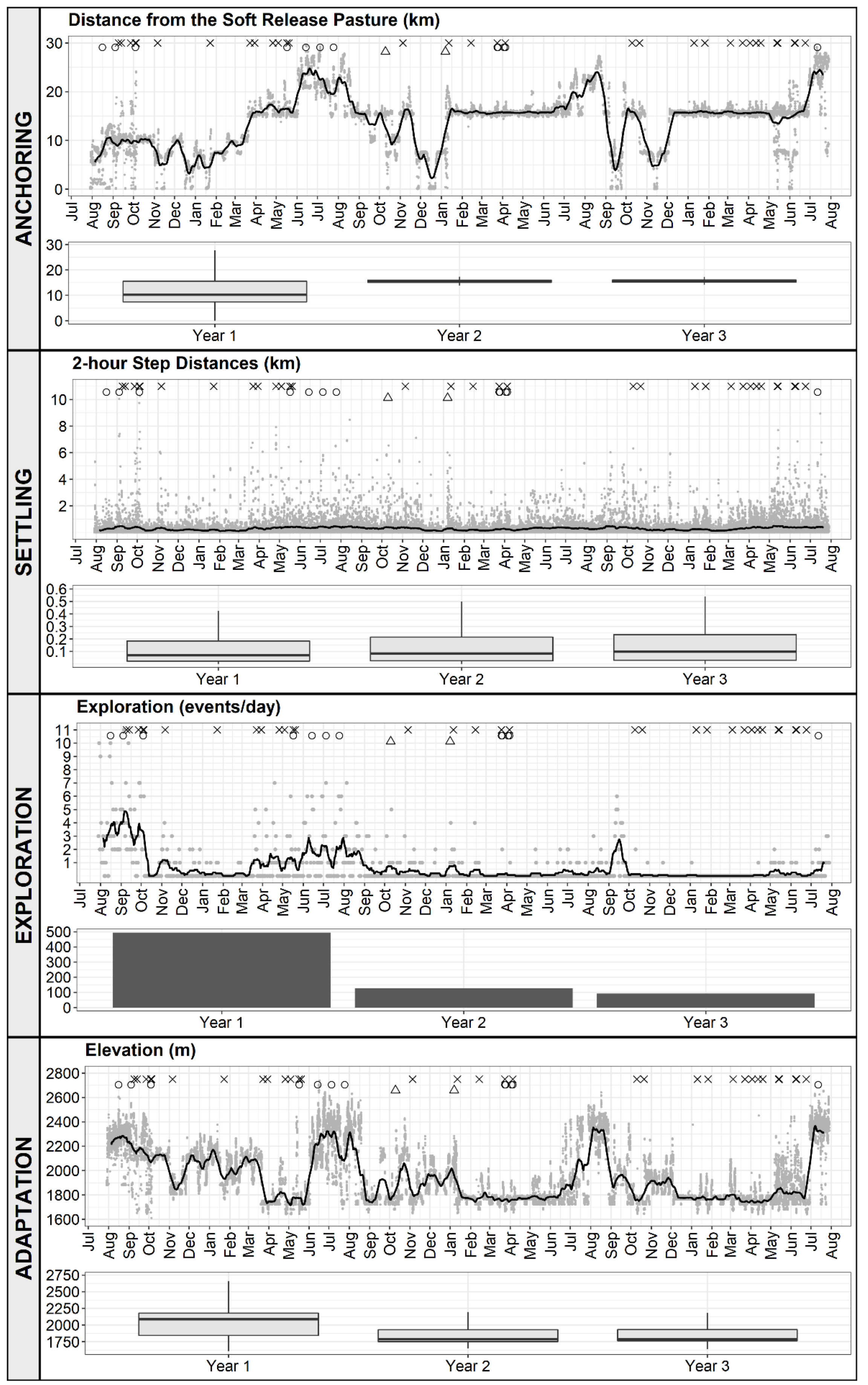

- Anchoring, or how animal fidelity to the soft-release pasture and the targeted reintroduction zone changed over time. A similarly designed reintroduction project for European bison (Bison bonasus) saw animals venture <8 km of the pasture for the first 6 months [28], whereas reintroduced elk (Cervus canadensis) dispersed 8–19.7 km over 2 years, depending on age and sex class, with an inverse relationship between time spent inside the enclosure and dispersal distance afterwards [29]. Based on these results, we expected the Banff bison to remain within 10 km of the soft-release pasture for the first 6 months, and for fencing and hazing interventions to limit their range to <30 km from the soft-release pasture thereafter. We expected the need for such interventions to decrease with time as the animals learned the boundaries of the target reintroduction zone, and an initially high return rate to the soft-release pasture to wane after the first year with lower rates of return afterwards.

- (2)

- Settling, or how bison behavioral states, as measured by step lengths and turning angles, shifted over time [30,31]. We expected bison to spend a higher proportion of their time in a “travelling” state immediately after release (i.e., longer step lengths with straighter paths) and shift to “feeding-resting” states (i.e., shorter steps with more frequent turns) as they adjusted to their new surroundings. Step lengths for an established wild plains bison population in Prince Albert National Park averaged 70 m per hour [32], so we expected bi-hourly step lengths to be initially elevated immediately after the release of the Banff bison (>200 m every 2 h) and to then decrease as the animals grew accustomed to their new home range. We also expected large surges (i.e., step lengths > 4 km in 2 h) to be rare, and to decrease with time.

- (3)

- Exploration, or the rate at which bison ventured into new, previously unvisited areas. A study of reintroduced European bison [28] recorded multiple, discrete pulses of exploration, with very high rates in the initial days, followed by reduced rates as newly familiar areas became bases from which the animals staged further exploration. Exploratory pulses continued to the end of their 6-month study period. Other studies of reintroduced ungulates showed exploration and home-range establishment occurring in distinct phases and within a wide range of timescales. For example, elk reintroduced to the Missouri Ozarks transitioned from a dispersive phase to a home-ranging phase after only 10 days [21] while elk introduced to the Bancroft region of Ontario took 1–3 years before settling into home-ranging movements [29]. Based on these trends, we expected exploration to be high for the Banff bison in the first week, and then to pulse upwards several times for up to a year before stabilizing at low levels. We expected the home-range size to similarly shrink and stabilize within a year.

- (4)

- Adaptation, or the tendency for bison to explore and exploit the novel, rugged, high-elevation mountain habitat versus the valley bottom meadows that are like the flat, low-elevation habitat they were translocated from in Elk Island National Park. The theory of natal habitat preference induction (NHPI) predicts dispersing animals will select similar areas to those they came from to minimize risk of assessing unfamiliar habitats [4]. We, therefore, expected the Banff bison to initially prefer low-elevation, valley-bottom meadow habitats and not to explore higher elevation habitats until a year or more had passed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Animals and the Soft-Release Pasture

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Anchoring

2.3.2. Settling

2.3.3. Exploration

2.3.4. Adaptation

2.3.5. Statistical Tests across Themes

3. Results

3.1. Anchoring

3.2. Settling

3.3. Exploration

3.4. Adaptation

4. Discussion

4.1. Anchoring

4.2. Settling

4.3. Exploration

4.4. Adaptation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seddon, P.J.; Armstrong, D.P.; Maloney, R.F. Developing the Science of Reintroduction Biology. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, E.W.; Redford, K.H.; Weber, B.; Aune, K.; Baldes, D.; Berger, J.; Carter, D. The Ecological Future of the North American Bison: Conceiving Long-Term, Large-Scale Conservation of Wildlife. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, T.; Norcross, D. Bison Reintroduction in Jasper National Park; Interim Report; Jasper National Park: Jasper, AB, Canada, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stamps, J.; Swaisgood, R. Someplace like Home: Experience, Habitat Selection and Conservation Biology. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 102, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Larter, N.C. Observations of Long-Distance Post-Release Dispersal by Reintroduced Bison (Bison Bison). Can. Field-Nat. 2017, 131, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, A.C. The Destruction of the Bison an Environmental History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 1750–1920. ISBN 978-0-511-54986-1. [Google Scholar]

- Langemann, E.G. Zooarchaeological Research in Support of a Reintroduction of Bison to Banff National Park, Canada. In The Future from the Past: Archaeozoology in Wildlife Conservation and Heritage Management; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kopjar, N.R. Alternatives for Bison Management in Banff National Park. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Steenweg, R.; Hebblewhite, M.; Gummer, D.; Low, B.; Hunt, B. Assessing Potential Habitat and Carrying Capacity for Reintroduction of Plains Bison (Bison Bison Bison) in Banff National Park. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks Canada. What We Heard: Summary of Public Comment for Plains Bison Reintroduction for Banff National Park; Parks Canada: Banff, AB, Canada, 2015; 4p.

- Parks Canada. Reintroduction Plan: Plains Bison in Banff National Park; Parks Canada: Banff, AB, Canada, 2015; 13p.

- Heuer, K. Detailed Environmental Impact Analysis, Plains Bison Reintroduction in Banff National Park: Pilot Project 2017–2022; Parks Canada: Banff, AB, Canada, 2017; 136p.

- Roe, F.G. The North American Buffalo; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.J.; Wallen, R.; Hallac, D. Yellowstone Bison: Conserving an American Icon in Modern Society; U.S. National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Bergeson, D. A Comparative Assessment of Management Problems Associated with the Free-Roaming Bison in Prince Albert National Park. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, B.; Hersey, K. Lessons Learned from Bison Restoration Efforts in Utah. Rangelands 2017, 38, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, J.A.; Cherry, S.G.; Fortin, D. Bison distribution under conflicting foraging strategies: Site fidelity vs. energy maximization. Ecology 2015, 96, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larter, N.C.; Gates, C.C. Home-range size of wood bison: Effects of age, sex, and forage availability. J. Mammal. 1994, 75, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, M. Evaluation of Boundary Control for Bison of Yellowstone National Park. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1989, 17, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.S. Extralimital Movements of Reintroduced Bison (Bison Bison): Implications for Potential Range Expansion and Human-Wildlife Conflict. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2017, 63, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleisch, A.D.; Keller, B.J.; Bonnot, T.W.; Hansen, L.P.; Millspaugh, J.J. Initial Movements of Re- Introduced Elk in the Missouri Ozarks. Am. Midl. Nat. 2017, 178, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremeniuk, T. (Canadian Bison Association, Regina, SK, Canada). Personal communication, 2016.

- Parker, I.D.; Watts, D.E.; Lopez, R.R.; Silvy, N.J.; Davis, D.S.; Mccleery, R.A.; Frank, P.A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Florida Key Deer Translocations. J. Wildl. Manag. 2008, 72, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, S.J.; Sperry, J.H.; DeGregorio, B.A. Effects of Antipredator Training, Environmental Enrichment, and Soft Release on Wildlife Translocations: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol. Cons. 2019, 236, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertes, K.; Stabach, J.A.; Songer, M.; Wacher, T.; Newby, J.; Chuven, J.; Dhaheri, S.A.; Leimgruber, P.; Monfort, S. Management Background and Release Conditions Structure Post-Release Movements in Reintroduced Ungulates. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 470. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2019.00470 (accessed on 1 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Laskin, D.N.; Watt, D.J.; Whittington, J.; Heuer, K. Designing a Fence That Enables Free Passage of Wildlife While Containing Reintroduced Bison: A Multispecies Evaluation. Wild. Biol. 2020, 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, D.J.; Heuer, K. Low-stress stockmanship as a tool in the reintroduction of wild plains bison to Banff National Park. Stockm. J. 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, P.; Caspers, S.; Warren, P.; Witte, K. First Steps into the Wild—Exploration Behavior of European Bison after the First Reintroduction in Western Europe. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckman, M.J.; Rosatte, R.C.; McIntosh, T.; Hamr, J.; Jenkins, D. Postrelease Dispersal of Reintroduced Elk (Cervus Elaphus) in Ontario, Canada. Rest. Ecol. 2010, 18, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.A.; Thomas, L.; Wilcox, C.; Ovaskainen, O.; Matthiopoulos, J. State–space models of individual animal movement. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, J.M.; Hazell, M.; Börger, L.; Dalziel, B.D.; Haydon, D.T.; Morales, J.M.; McIntosh, T.; Rosatte, R.C. Multiple movement modes by large herbivores at multiple spatiotemporal scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19114–19119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.N.; Fortin, D. Crop Raiders in an Ecological Trap: Optimal Foraging Individual-Based Modeling Quantifies the Effect of Alternate Crops. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelot, T.; Langrock, R.; Patterson, T.A. MoveHMM: An R Package for the Statistical Modelling of Animal Movement Data Using Hidden Markov Models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielson, R.M.; Sawyer, H.; McDonald, T.L. BBMM: Brownian Bridge Movement Model for Esti-Mating the Movement Path of an Animal Using Discrete Location Data. R package Version 3.0. 2013. Available online: http://cran.r-project.org/package=BBMM (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Horne, J.; Lewis, J.S. Analyzing animal movements using brownian bridges. Ecology 2007, 88, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, W.D.; Onorato, D.P.; Fischer, J.W. Is There a Single Best Estimator? Selection of Home Range Estimators Using Area-under-the-Curve. Mov. Ecol. 2015, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W. Bonferroni Correction. In Encyclopedia of Systems Biology; Dubitzky, A., Wolkenhauer, O., Cho, K.H., Yokota, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B. Probable Inference, the Law of Succession, and Statistical Inference. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1927, 22, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebblewhite, M.; Merrill, E.H.; Morgantini, L.E.; White, C.A.; Allen, J.R.; Bruns, E.; Thurston, L.; Hurd, T.E. Is the Migratory Behavior of Montane Elk Herds in Peril? The Case of Alberta’s Ya Ha Tinda Elk Herd. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2006, 34, 1280–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, T. Social behavior of the American Buffalo (Bison bison bison). Zoologica 1958, 43, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, L.J.; Coogan, S.C.P.; Nielsen, S.E.; Edwards, M.A. Latitudinal and Seasonal Plasticity in American Bison Bison Bison Diets. Mamm. Rev. 2021, 51, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebblewhite, M.A.; Merrill, E.H.; McDermid, G. A Multi-Scale Test of the Forage Maturation Hypothesis in a Partially Migratory Ungulate Population. Ecol. Monogr. 2008, 78, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, J.A.; Monteith, K.L.; Aikens, E.O.; Hayes, M.M.; Hersey, K.R.; Middleton, A.D.; Oates, B.A.; Sawyer, H.; Scurlock, B.M.; Kauffman, M.J. Large Herbivores Surf Waves of Green-up during Spring. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2016, 283, 20160456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagemoen, R.I.M.; Reimers, E. Reindeer Summer Activity Pattern in Relation to Weather and Insect Harassment. J. Anim. Ecol. 2002, 71, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuren, D. Group Dynamics and Summer Home Range of Bison in Southern Utah. J. Mammal. 1983, 64, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

= 30-day moving average. × = drift fence encounter. ○ = herding event. Δ = helicopter capture.

= 30-day moving average. × = drift fence encounter. ○ = herding event. Δ = helicopter capture.

= 30-day moving average. × = drift fence encounter. ○ = herding event. Δ = helicopter capture.

= 30-day moving average. × = drift fence encounter. ○ = herding event. Δ = helicopter capture.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zier-Vogel, A.; Heuer, K. The First 3 Years: Movements of Reintroduced Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) in Banff National Park. Diversity 2022, 14, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14100883

Zier-Vogel A, Heuer K. The First 3 Years: Movements of Reintroduced Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) in Banff National Park. Diversity. 2022; 14(10):883. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14100883

Chicago/Turabian StyleZier-Vogel, Adam, and Karsten Heuer. 2022. "The First 3 Years: Movements of Reintroduced Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) in Banff National Park" Diversity 14, no. 10: 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14100883

APA StyleZier-Vogel, A., & Heuer, K. (2022). The First 3 Years: Movements of Reintroduced Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) in Banff National Park. Diversity, 14(10), 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14100883