Mires in Europe—Regional Diversity, Condition and Protection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definitions

2.2. Peatland Distribution

2.3. Peatland Condition

2.4. Protected Areas

3. Results

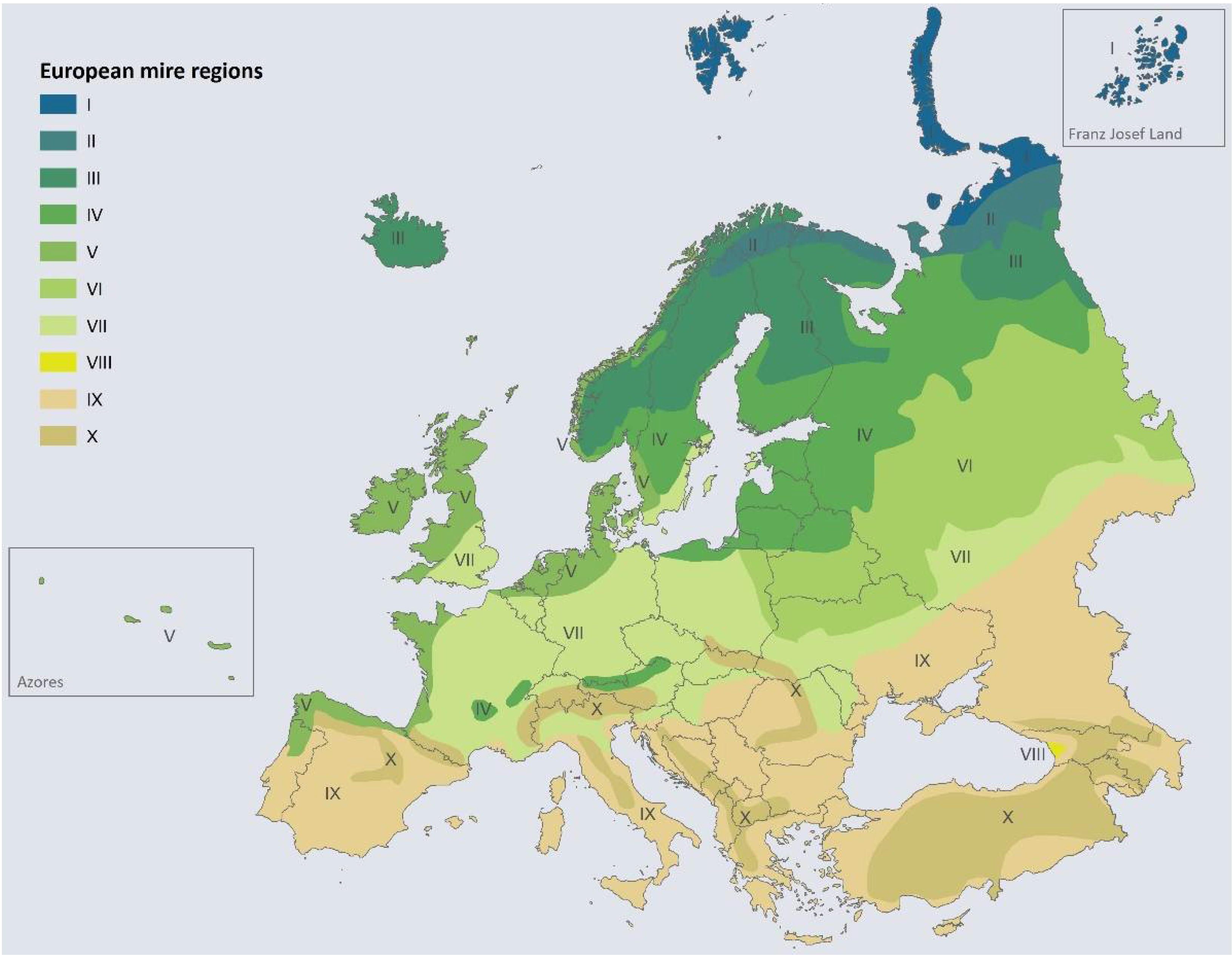

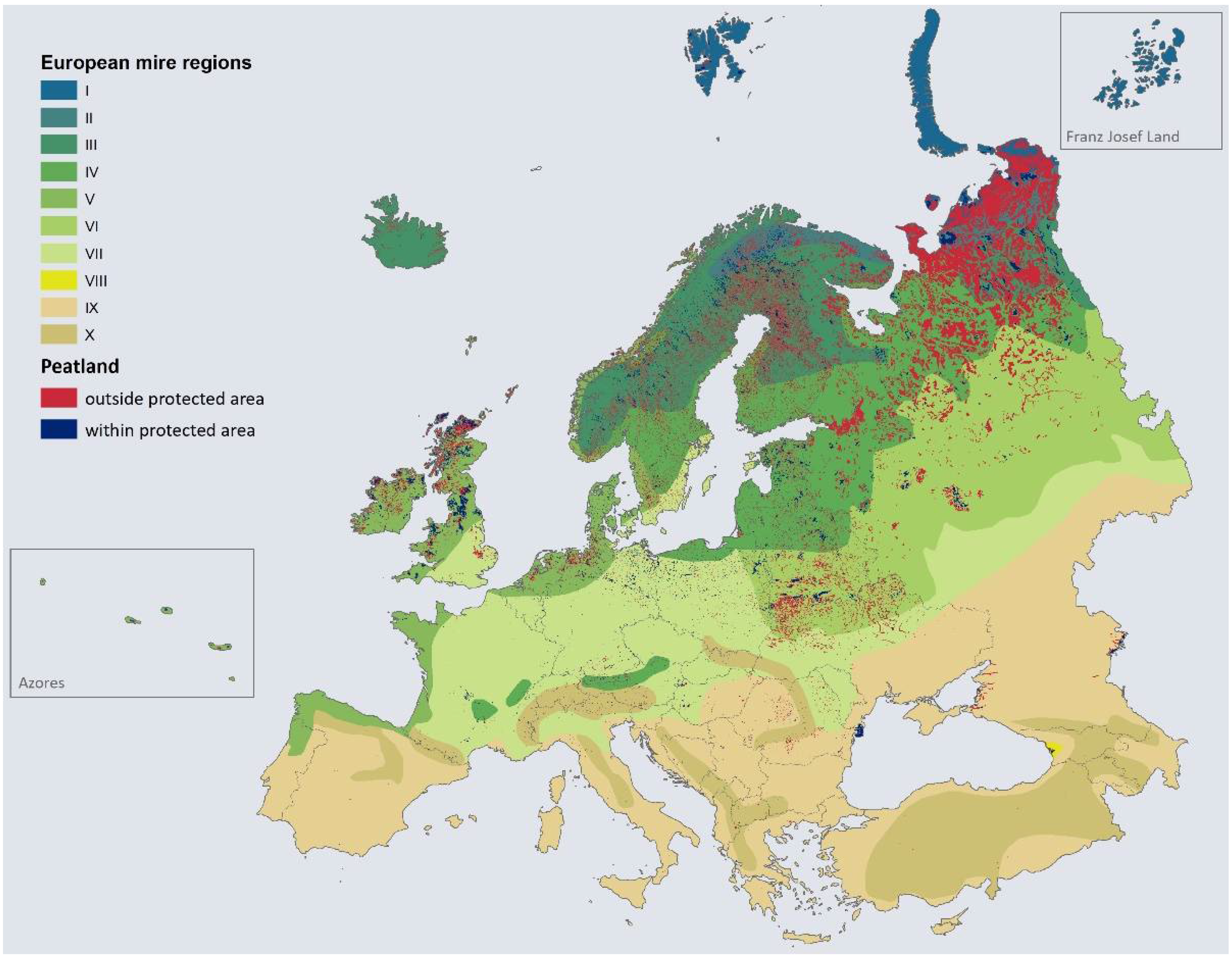

3.1. Peatland Cover

3.2. Peatland Condition

3.3. Peatland Protection

3.4. Overview and Key Characteristics of the Ten Mire Regions of Europe

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Quality

4.2. Designation of Protected Areas vs. Peatland Protection

- The most important criteria for identifying mires of international conservation importance are similar to those on a local/national scale. The local criterion ‘representativeness’ identifies ‘rareness’ on an international scale. The local criterion ‘rareness’ normally identifies mire components that on an international scale are either rare, or at the margin of/outside their main distribution area. Such marginal/azonal occurrences are ‘distinctive’ and have a high conservational value [43,44].

- Application of objective selection criteria, and the use of optimally efficient selection strategies indicate that a very large number of protected areas (and a very large area) are necessary to secure biological diversity. In the framework of the climate and biodiversity crisis, the protection of all still-pristine peatlands and the rewetting/restoration of all drained and otherwise degraded peatlands is necessary.

- Management should be guided by nature conservation (natural biodiversity purposes) especially in strictly protected areas, and by provision of other ecosystem services (regulating and provisioning services) in less strictly protected areas (e.g., biosphere reserves) and in the unprotected peatland areas (e.g., enhanced by appropriate agricultural funding schemes).

- For all protected peatlands, it is fundamental to also protect their catchment (see below).

- Different mire types may be functionally connected, for example petrifying springs and spring fens, both protected habitat types under EU law. This implies that restoration of damaged petrifying springs and spring fens should aim at restoring the complexes as a whole with both habitats included, and should not focus solely on the separate habitat types [45].

4.3. Lessons Learnt from Europe

- Peatland conservation implies primarily the conservation of its hydrology. Even small drops of the water level can affect peat accumulation and conservation and initiate ongoing peatland degradation.

- To conserve a peatland, its entire ‘hydrological unit’ has to be conserved, i.e., the entire peat body and—certainly in cases of groundwater fed systems—also the mineral catchment area and hydrological buffer zone.

- If peatlands must be used, they should be used wet [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. This recent insight has not yet resulted in large scale implementation of suitable production techniques, because the techniques and rules and modalities still have to be developed, accepted and adapted [50].

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parish, F.; Sirin, A.; Charman, D.; Joosten, H.; Minayeva, T.; Silvius, M.; Stringer, L. (Eds.) Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change; Global Environment Centre and Wetlands International: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H. Sensitising global conventions for climate change mitigation by peatlands. In Carbon Credits from Peatland Rewetting. Climate—Biodiversity—Land Use; Tanneberger, F., Wichtmann, W., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2011; pp. 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H.; Tapio-Biström, M.-L.; Tol, S. (Eds.) Peatlands—Guidance for Climate Change Mitigation through Conservation, Rehabilitation and Sustainable Use, 2nd ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Wetlands International: Rome, Italy; Ede, Netherlands, 2012; p. 114. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-an762e.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Biancalani, R.; Avagyan, A. (Eds.) Towards Climate-Responsible Peatlands Management; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2014; p. 117. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4029e.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- IPCC. 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands; Hiraishi, T., Krug, T., Tanabe, K., Srivastava, N., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Troxler, T.G., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin, A.; Minayeva, T.; Joosten, H.; Tanneberger, F. 3.3.2.8 Peatlands. In The IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Europe and Central Asia; Rounsevell, M., Fischer, M., Torre-Marin Rando, A., Mader, A., Eds.; Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2018; pp. 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn, A.; Allott, T.; Evans, M.; Joosten, H.; Stoneman, R. (Eds.) Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice; Cambridge University Press/British Ecological Society: Cambridge, UK, 2016; p. 493. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Resolution Adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly on 15 March 2019. 4/16. Conservation and Sustainable Management of Peatlands. 2019. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/28480/English.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Maltby, E.; Caseldine, C.J. Prehistoric soil and vegetation development on Bodmin Moor, southwestern England. Nature 1982, 297, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, H.; Clarke, D. Wise Use of Mires and Peatlands: Background and Principles Including a Framework for Decision-Making; International Mire Conservation Group and International Peat Society: Saarijärvi, Finland, 2002; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H. Human impacts: Farming, fire, forestry and fuel. In The Wetlands Handbook; Maltby, E., Barker, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 689–718. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H.; Tanneberger, F. Peatland use in Europe. In Mires and Peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, L.J. Holocene peat formation in the lower parts of the Netherlands. In Fens and Bogs in The Netherlands: Vegetation, History, Nutrient Dynamics and Conservation; Verhoeven, J.T.A., Ed.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 7–79. [Google Scholar]

- Törnqvist, T.E.; Joosten, J.H.J. On the origin and development of a Subatlantic “man-made” mire in Galicia (northwest Spain). Proc. Int. Peat Congr. 1988, I, 214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, P.D. The origin of blanket mire, revisited. In Climate Change and Human Impact on the Landscape; Chambers, F.M., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1993; pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kaland, P.E. The origin and management of Norwegian coastal heaths as reflected by pollen analysis. In Anthropogenic Indicators in Pollen Diagrams; Behre, K.-E., Ed.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, R.; Clough, J. United Kingdom. In Mires and Peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 705–719. [Google Scholar]

- Tanneberger, F.; Tegetmeyer, C.; Busse, S.; Barthelmes, A.; Shumka, S.; Moles Marine, A.; Jenderedjian, K.; Steiner, G.M.; Essl, F.; Etzold, J.; et al. The peatland map of Europe. Mires Peat 2017, 19, 1–17. Available online: http://mires-and-peat.net/pages/volumes/map19/map1922.php (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Joosten, H. The Global Peatland CO2 Picture. Peatland Status and Drainage Related Emissions in all Countries of the World; Wetlands International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Barthelmes, A. The global potential and perspectives for paludiculture. In Paludiculture—Productive Use of Wet Peatlands. Climate Protection—Biodiversity—Regional Economic Benefits; Wichtmann, W., Schröder, C., Joosten, H., Eds.; Schweizerbart Science Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; pp. 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm, T.; Heikkilä, R. Finland. In Mires and Peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 376–394. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H.; Grootjans, A.; Schouten, M.; Jansen, A. The Netherlands. In Mires and Peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 523–525. [Google Scholar]

- Cajander, A.K. Studien über die Moore Finnlands. [Studies of the mires of Finland]. Acta For. Fenn. 1913, 2, 1–208. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bülow, K. Die deutschen Moorprovinzen. [The German mire provinces]. Jahrb. Der Preußischen Geol. Landesanst. 1928, 49, 207–219. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Katz, N.Y. Zur Kenntnis der Moore Nordosteuropas. [On the peatlands of Northeastern Europe]. Beih. Bot. Zbl. 1930, 2, 287–394. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Kats, N.Y.; Кац, Н.Я. Типы бoлoт СССР и Западнoй Еврoпы и их геoграфическoе распрoстранение. [Mire types of the USSR and Western Europe and their geographical distribution]. Geogr. Mosk. 1948, 320. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Moen, A.; Joosten, H.; Tanneberger, F. Mire diversity in Europe: Mire regionality. In Mires and Peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 97–150. [Google Scholar]

- Eurola, S.; Vorren, K.D. Mire zones and sections in North Fennoscandia. Aquil. Ser. Bot. 1980, 17, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H.; Tanneberger, F.; Moen, A. Mires and Peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use; National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, IGES: Japan, Tokyo, 2006; Volume 4, Available online: http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/vol4.html (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Bohn, U.; Gollub, G.; Hettwer, C.; Weber, H.; Neuhäuslová, Z.; Raus, T.; Schlüter, H. Karte der Natürlichen Vegetation Europas. [Map of the Natural Vegetation of Europe]. Maßstab 1:2,500,000. [Scale 1:2,500,000] Teil 1: Erläuterungstext. [Part 1: Explanatory text] 655 p. Teil 2: Legende. [Part 2: Legend] 153 p. Teil 3: Karten: 9 Blätter + Legendenblatt + Übersichtskarte 1:10,000,000. [Part 3: Maps: 9 Sheets + Legend Sheet + General Map 1:10,000,000] Teil 4: Interaktive CD-ROM, Erläuterungstext, Legende, Karten. [Part 4: Interactive CD-ROM, Explanatory Text, Legend, Maps], 2000–2004; Landwirtschaftsverlag: Münster, Germany, 2004; Available online: https://is.muni.cz/el/1431/podzim2012/Bi9420/um/Bohn_etal2004_Map-Nat-Veg-Europe.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2021). (In German)

- Tegetmeyer, C.; Barthelmes, K.-D.; Busse, S.; Barthelmes, A. Aggregierte Karte organischer Böden Deutschlands; Greifswald Mire Centre: Greifswald, Germany, 2020; p. 10. ISSN 2627-910X. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Buchhorn, M.; Smets, B.; Bertels, L.; Lesiv, M.; Tsendbazar, N.-E.; Masiliunas, D.; Linlin, L.; Herold, M.; Fritz, S. Copernicus Global Land Service: Land Cover 100 m: Collection 3: Epoch 2019: Globe. Zenodo 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN. Protected Planet. 2020. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Deguignet, M.; Arnell, A.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Shi, Y.; Bingham, H.; MacSharry, B.; Kingston, N. Measuring the extent of overlaps in protected area designations. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minayeva, T.; Sirin, A.; Bragg, O. (Eds.) A Quick Scan of Peatlands in Central and Eastern Europe; Wetlands International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin, A.; Minayeva, T.; Yurkovskaya, T.; Kuznetsov, O.; Smagin, V.; Fedotov, Y.U. Russian Federation (European Part). In Mires and peatlands of Europe. Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 589–616. [Google Scholar]

- Minayeva, T.Y.; Bragg, O.M.; Sirin, A.A. Towards ecosystem-based restoration of peatland biodiversity. Mires Peat 2017, 19, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmes, A. (Ed.) Reporting Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Organic Soils in the European Union: Challenges and Opportunities. Policy Brief; Greifswald Mire Centre: Greifswald, Germany, 2018; p. 16. ISSN 2627-910X. [Google Scholar]

- Manton, M.; Makrickas, E.; Banaszuk, P.; Kołos, A.; Kamocki, A.; Grygoruk, M.; Stachowicz, M.; Jarašius, L.; Zableckis, N.; Sendžikaite, J.; et al. Assessment and Spatial Planning for Peatland Conservation and Restoration: Europe’s Trans-Border Neman River Basin as a Case Study. Land 2021, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back into our Lives. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:a3c806a6-9ab3-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- United Nations Environment Programme. First Draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. 2021. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/914a/eca3/24ad42235033f031badf61b1/wg2020-03-03-en.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Joosten, H. A world of mires: Criteria for identifying mires of global conservation significance. In Peatlands Use—Present, past and Future; Lüttig, G.W., Ed.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 1996; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H. Identifying Peatlands of International Biodiversity Importance. 2001. Available online: http://www.imcg.net/pages/publications/papers/identifying-peatlands-of-international-biodiversity-importance.php (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Grootjans, A.P.; Wołejko, L.; de Mars, H.; Smolders, A.J.P.; van Dijk, G. On the hydrological relationship between Petrifying-springs, Alkaline-fens, and Calcareous-spring-mires in the lowlands of North-West and Central Europe; consequences for restoration. Mires Peat 2021, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H. Ramsar Global Guidelines for Peatland Rewetting and Restoration; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Greifswald Mire Centre (GMC); Wetlands International; National University of Ireland (NUI) Galway. Peatlands in the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) After 2020. Position Paper. 2020. Available online: https://www.greifswaldmoor.de/files/dokumente/Infopapiere_Briefings/202003_CAP%20Policy%20Brief%20Peatlands%20in%20the%20new%20EU%20Version%204.8.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Tanneberger, F.; Appulo, L.; Ewert, S.; Lakner, S.; Brolcháin, N.Ó.; Peters, J.; Wichtmann, W. The Power of Nature-based Solutions: How peatlands can help us to achieve key EU sustainability objectives. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 5, 2000146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, W.; Schröder, C.; Joosten, H. (Eds.) Paludiculture—Productive Use of Wet Peatlands; Schweizerbart Science Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, R.; Wichtmann, W.; Abel, S.; Kemp, R.; Simard, M.; Joosten, H. Wet peatland utilisation for climate protection—An international survey of paludiculture innovation. J. Clean. Prod. submitted.

| Nb. | Mire Region | Mire Massif Type | Total Peatland Area | Degraded Peatlands | Degraded Peatlands excl. European Russia | Degraded Peatlands EU27 Countries Only | Peatlands in Protected Areas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Additional | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | ||

| I | Arctic seepage and polygon mire region | Tundra seepage and polygon fen | Palsa mire; Flat fen & marsh | 62,700 | 6 | 600 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 7100 | 11 |

| II | Palsa mire region | Palsa mire | String-flark fen types and mixed mires | 147,100 | 13 | 8700 | 6 | 1900 | 16 | 1400 | 21 | 13,700 | 9 |

| III | Northern fen region | String-flark fen types and mixed mires | Rim raised bog; Blanket bog; Plane bog; Percolation fen; Flat fen & marsh | 300,600 | 27 | 57,800 | 26 | 49,700 | 36 | 43,400 | 40 | 39,900 | 13 |

| IV | Typical raised bog region | Typical raised bog; Wooded raised bog | Plane bog; Flat fen & marsh | 341,700 | 31 | 88,100 | 26 | 33,400 | 49 | 26,900 | 50 | 34,600 | 10 |

| V | Atlantic bog region | Atlantic raised bog; Blanket bog | Plane bog; Flat fen & marsh | 64,200 | 6 | 43,500 | 68 | 43,500 | 68 | 22,800 | 75 | 35,900 | 56 |

| VI | Continental fen and bog region | Wooded raised bog | Plane bog; Percolation fen; Flat fen & marsh | 130,900 | 12 | 48,900 | 37 | 20,100 | 58 | 2900 | 63 | 19,700 | 15 |

| VII | Nemoral-submeridional fen region | Flat fen & marsh | Plane bog; Percolation fen | 30,600 | 3 | 19,300 | 63 | 19,300 | 63 | 17,500 | 66 | 13,700 | 45 |

| VIII | Colchis mire region | Percolation bog | Flat fen & marsh | 600 | <1 | 30 | 5 | 30 | 5 | - | - | 300 | 44 |

| IX | Southern European marsh region | Flat fen & marsh | - | 16,000 | 2 | 8500 | 53 | 3800 | 47 | 3500 | 47 | 6800 | 43 |

| X | Central and southern European mountain compound region | Flat fen & marsh | Sloping fen; Plane bog; Percolation fen | 4000 | <1 | 1300 | 32 | 1200 | 32 | 1500 | 44 | 2200 | 56 |

| Total | - | - | 1,082,400 | 100 | 276,700 | 25 | 172,900 | 48 | 120,000 | 50 | 174,700 | 16 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanneberger, F.; Moen, A.; Barthelmes, A.; Lewis, E.; Miles, L.; Sirin, A.; Tegetmeyer, C.; Joosten, H. Mires in Europe—Regional Diversity, Condition and Protection. Diversity 2021, 13, 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13080381

Tanneberger F, Moen A, Barthelmes A, Lewis E, Miles L, Sirin A, Tegetmeyer C, Joosten H. Mires in Europe—Regional Diversity, Condition and Protection. Diversity. 2021; 13(8):381. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13080381

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanneberger, Franziska, Asbjørn Moen, Alexandra Barthelmes, Edward Lewis, Lera Miles, Andrey Sirin, Cosima Tegetmeyer, and Hans Joosten. 2021. "Mires in Europe—Regional Diversity, Condition and Protection" Diversity 13, no. 8: 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13080381

APA StyleTanneberger, F., Moen, A., Barthelmes, A., Lewis, E., Miles, L., Sirin, A., Tegetmeyer, C., & Joosten, H. (2021). Mires in Europe—Regional Diversity, Condition and Protection. Diversity, 13(8), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13080381