Abstract

A review of the Mexican rotifer species diversity is presented here. To date, 402 species of rotifers have been recorded from Mexico, besides a few infraspecific taxa such as subspecies and varieties. The rotifers from Mexico represent 27 families and 75 genera. Molecular analysis showed about 20 cryptic taxa from species complexes. The genera Lecane, Trichocerca, Brachionus, Lepadella, Cephalodella, Keratella, Ptygura, and Notommata accounted for more than 50% of all species recorded from the Mexican territory. The diversity of rotifers from the different states of Mexico was highly heterogeneous. Only five federal entities (the State of Mexico, Michoacán, Veracruz, Mexico City, Aguascalientes, and Quintana Roo) had more than 100 species. Extrapolation of rotifer species recorded from Mexico indicated the possible occurrence of more than 600 species in Mexican water bodies, hence more sampling effort is needed. In the current review, we also comment on the importance of seasonal sampling in enhancing the species richness and detecting exotic rotifer taxa in Mexico.

1. Introduction

Taxonomical studies involving species richness provide information on the global patterns of species distribution and are helpful to detect changes associated with climate or global trade. For example, in Mexico, the number of exotic and thus invasive species has been steadily increasing during the last two decades [1,2]. The existence of taxonomic checklists is helpful to confirm this.

Mexico is one of the megadiverse countries and accounts for about 10% of the world’s biodiversity [3]. Despite well-classified geographical regions of Mexico [4], the description of the distribution of different groups of animal species is still fragmentary, especially with reference to invertebrates, including rotifers. Freshwater zooplanktonic groups are mainly composed of ciliates, rotifers, cladocerans, and copepods. Rotifers, being important trophic links in aquatic ecosystems, have been the focus of basic research, such as taxonomy and autecology, and applied aspects, such as ecotoxicology, aquaculture, and water quality indicators [5].

Studies on the rotifer species richness in Mexico have been steadily gaining importance during the last 25 years. Earlier studies were mainly sporadic and, at times, biased, with a limnological perspective [6]. Species checklists of rotifers from the Mexican territory are available only for selected regions. For example, information about the distribution of rotifers exists for the State of Mexico, Aguascalientes, Michoacán, Mexico City, and a few regions of the Yucatan Peninsula [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, larger parts of the Mexican territory still lack such information. The first national checklist of rotifers from Mexico was produced during the late 1990s [14]. Since then, considerable progress has been made on the distribution of rotifers in different regions, although no attempts have been made to update the checklist.

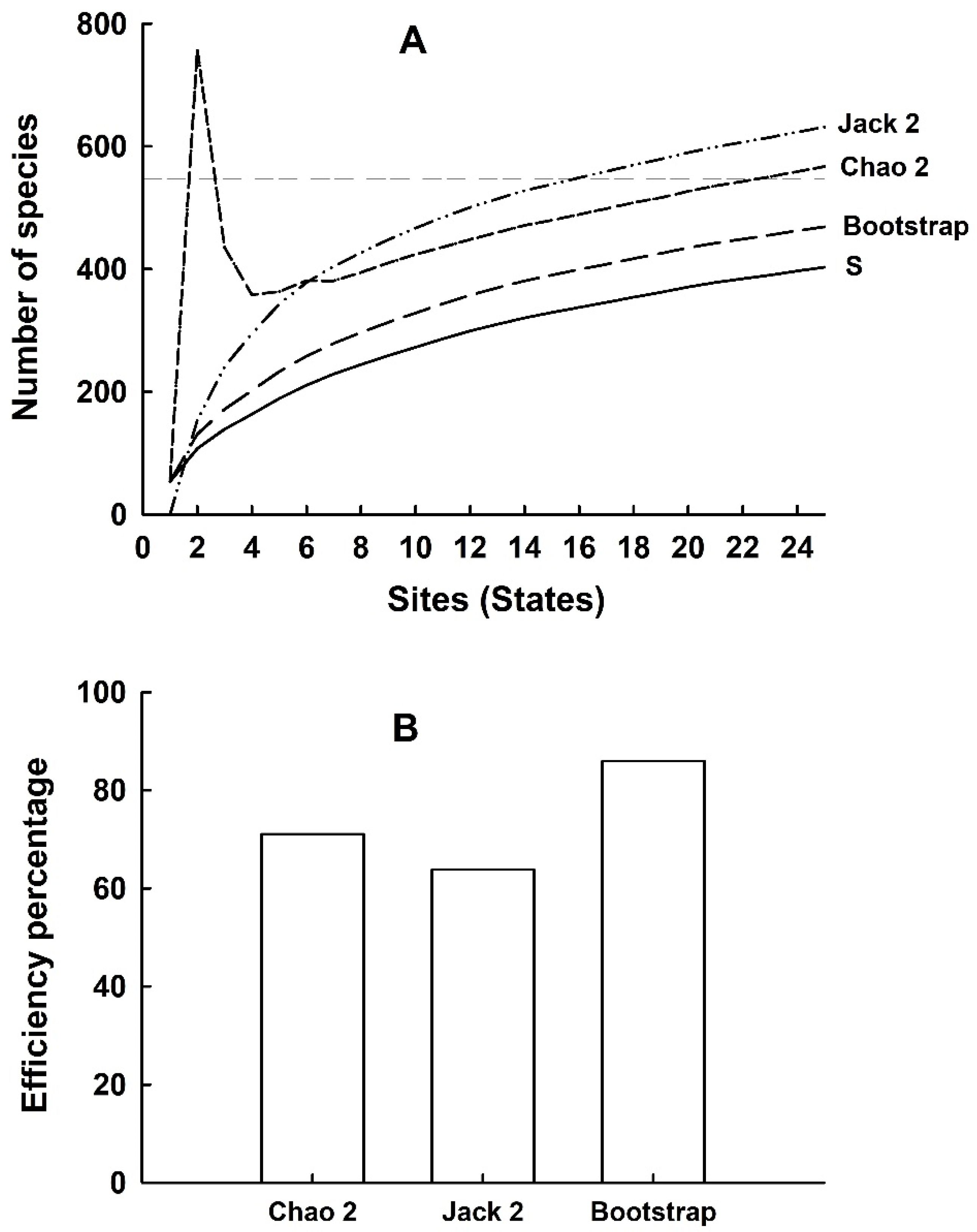

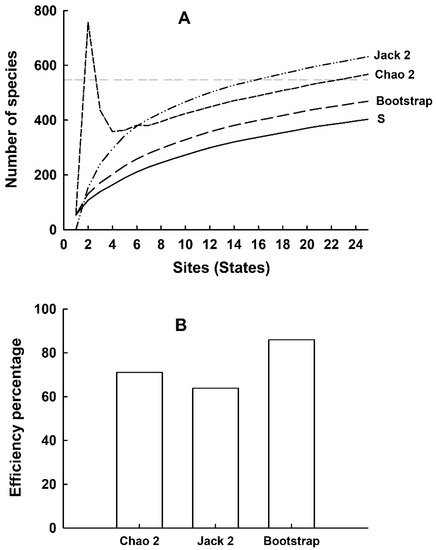

Numerous models and computer programs are available to predict the possible number of species in a region or nation based on species accumulation and rarefaction curves, the presence or absence of given taxa, etc. For example, for understanding the state of biodiversity, models such as ICE, Chao 2, Jackknife, and Bootstrap are traditionally used to obtain species estimates for different groups of organisms [15]. Significant errors may still occur if the published reports of species are not corrected or weak data with large sampling gaps are used. In Mexico, the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, CONABIO) contains data on the biodiversity of different groups of organisms, yet information on patterns of distribution of groups such as rotifers within its territorial jurisdiction are limited.

This work aimed to provide a comprehensive list of rotifer species recorded and document their distributional patterns from different regions of Mexico.

2. Materials and Methods

A bibliographic review of rotifer diversity studies from Mexico was conducted using the standard databases in the Web of Science using the search words “rotifer*”, “Mexic*” and “diversity” during the entire period available in each database (retrieved during May 2021). The records were then consulted in the full text, and we checked each work for the records of rotifer species. We also consulted works from other non-indexed journals but avoided contributions that contained only genus-level descriptions for rotifers. The data were sorted out into Excel files according to the geographical entities of Mexico. In addition, the documents available from CONABIO were also considered. For species nomenclature, we followed standard works on Rotifera [16,17]. The checklist provided here does not contain a listing of the infraspecific taxa. Therefore, only species were enumerated. However, infraspecific taxa were reported in the checklist without assigning an additional number.

Due to the increased accessibility of molecular tools in the study of systematics of rotifers, several cryptic taxa of commonly distributed species within genera such as Brachionus, Keratella, Asplanchna, and Lecane have been documented. However, cryptic species without formal description were not included in the checklist, although references to such studies are made in a separate table. When a known species was already reported from Mexico (e.g., Philodina roseola), the same taxon with conferatur status (e.g., Philodina cf. roseola) was not numbered. However, if a taxon was reported only with conferatur, it was considered for numbering (e.g., Notholca cf. liepetterseni). Further, taxa that have been identified as having potential species status but not described are not included here, for example, Brachionus sp. “Mexico” [18] and Hexarthra n. sp. [19]. In addition, as far as possible, we used published reports of species. When necessary, we checked the species identifications based on the illustrations provided in the articles with those from standard literature [20,21,22,23]. Yet, some taxa with species inquirenda status (e.g., Polyarthra trigla) were retained as such pending further studies. The species checklist was not arranged based on phylogeny of Rotifera. Rotifer families were arranged alphabetically, and within each family and genus, the species were all in alphabetic order. This facilitated reporting new records in future research.

A nonparametric analysis of species richness of Rotifera reported from Mexico was performed using the updated checklist. Models/computer simulations based on Chao 2, Jackknife 2, and Bootstrap were performed using EstimatesS 9 [24]. From the diversity estimators, we derived the efficiency percentage of each estimator with the following formula:

3. Results

Mexico has 31 states and a capital, Mexico City. The total number of rotifer species reported from Mexico was 402, besides a few infraspecific taxa such as subspecies and varieties. The list of consulted works is available in Supplementary 1 with coordinates for each federal entity obtained from the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). The database, created using published works from Mexican Rotifera, is presented in Supplementary 2. Rotifers from Mexico represented 27 families and 75 genera (Table 1). Only eight genera, viz., Lecane, Trichocerca, Brachionus, Cephalodella, Lepadella, Keratella, Ptygura, and Notommata, of rotifers had more than 50% of the total species recorded from the Mexican territory. Each of these genera had at least 10 species, while the remaining genera had less than 10 species each. Of the 15 species recorded with conferatur status, 11 were from Chihuahua and Quintana Roo. To date, molecular analysis has revealed the existence of 17 taxa as species complexes consisting of cryptic species (Table 2).

Table 1.

Checklist of rotifer species recorded from Mexico.

Table 2.

Some species complexes and cryptic species of rotifers reported from Mexico.

The faunal diversity of rotifers from the different states of the country was highly heterogeneous. Only five federal entities (the State of Mexico, Michoacán, Veracruz, Mexico City, and Quintana Roo) had more than 100 species. The total number of genera per state followed the same trend of species richness (Table 3). Thus, seven federal entities (the State of Mexico, Michoacán, Veracruz, Mexico City, Quintana Roo, Aguascalientes, and Chihuahua) had more than 30 genera.

Table 3.

Number of genera and species of rotifers reported from different States of Mexico. The states are represented by bold numbers. 1: Aguascalientes, 2: Campeche, 3: Chiapas, 4: Chihuahua, 5: Colima, 6: Guanajuato, 7: Guerrero, 8: Hidalgo, 9: Jalisco, 10: Mexico City, 11: Michoacan, 12: Morelos, 13: Nayarit, 14: Oaxaca, 15: Puebla, 16: Quintana Roo, 17: San Luis Potosi, 18: Sinaloa, 19: Sonora, 20: State of Mexico, 21: Tabasco, 22: Tlaxcala, 23: Veracruz, 24: Yucatán, 25: Zacatecas. Other states do not have published records of rotifers, and these were not included.

Seasonally collected samples offered a higher number of species than those collected sporadically. Data on the species richness of rotifers collected seasonally from selected water bodies are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The number of rotifer species reported from selected waterbodies through seasonal sampling.

Biogeographic distribution of selected species recorded from Nearctic and Neotropical regions of Mexico showed some of them to be out of known range based on global patterns. More than 20 taxa distributed in Palearctic region were reported from Nearctic or Neotropical regions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Out of known range distribution of Rotifera recorded from Mexico. The known range from different geographical regions was based on [16], and for the national biogeographic provinces, Ref. [4] was followed. Afr: Afrotropical region; Ant: Antarctic region; Aus: Australian region; Nea: Nearctic region; Neo: Neotropical region; Ori: Oriental region; Pac: Pacific region and Pal: Palearctic region.

Different estimators of species diversity indicated the asymptote in all cases (Figure 1). The efficiency percentage of species estimates varied between 62% and 86% (Chao 2 and Bootstrap, respectively). In addition, these estimators indicated that the potential richness of rotifers from Mexico could be from 450 to 600 species.

Figure 1.

Diversity estimators (A) and efficiency percentage (B) using Jack 2, Chao 2, and Bootstrap methods.

4. Discussion

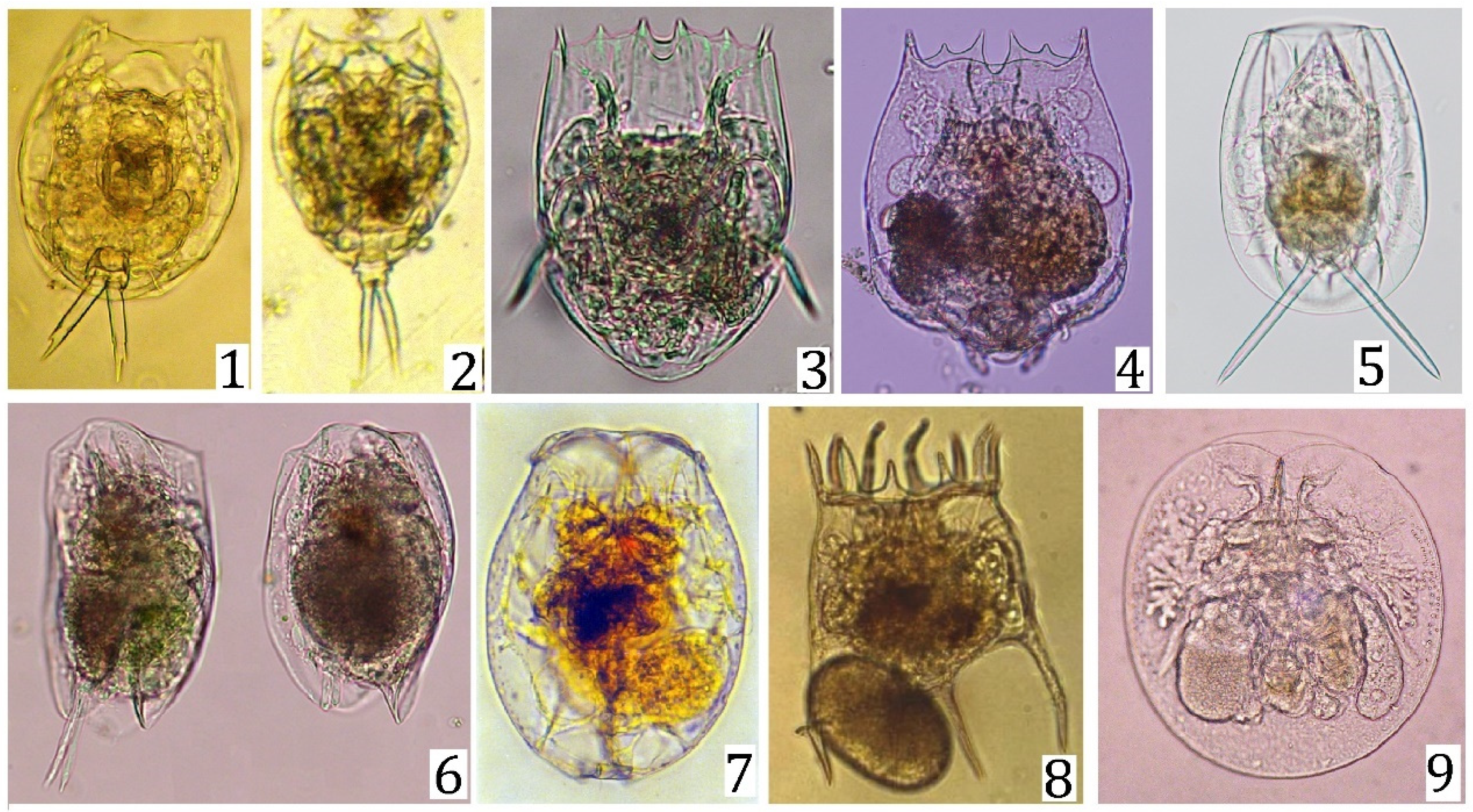

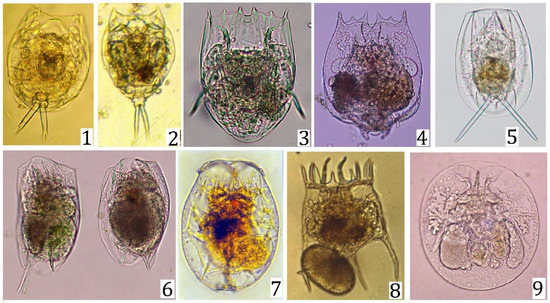

Taxonomical studies on Mexican rotifers date back more than 100 years. However, increased awareness of their role in limnological studies began only during the last 25 years. Figure 2 shows some of the interesting rotifer species from Mexico. Conventional limnological investigations in Mexico included rotifers as part of plankton [6], yet rarely quantified their abundances. One of the earliest studies on the seasonal variations of freshwater rotifers showed just seven rotifer taxa [43]. Thereafter, many studies on the seasonal variations of rotifers have been carried out from different water bodies such as ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and rivers. For certain freshwater ecosystems, zooplankton sampling was carried out for many years, for example, in the Valle de Bravo reservoir [44]. Long-term studies of riverine plankton are rare in Mexico, although the country has more than 200 rivers. Seasonal studies from River Antigua in the State of Veracruz have revealed 125 species REF. The importance of seasonal studies in understanding the rotifer species richness began receiving considerable attention after it became clear that certain exotic taxa appear only in certain months of the year. For example, Notholca cf. liepetterseni and Lecane yatseni have been recorded in River Antigua, Veracruz sporadically [40], although these species are native to the Scandinavian region and China, respectively.

Figure 2.

Some interesting rotifers from Mexico. (1) Lecane yatseni, (2) Lecane rhytida, (3) Notholca cf. liepetterseni, (4) Brachionus bidentatus, (5) Dipleuchlanis propatula; (6) Euchlanis cf. mikropous, (7) Brachionus dimidiatus, (8) Plationus patulus macracanthus and (9) Testudinella patina. All photos from authors’ previous works.

The first comprehensive list of Mexican rotifers was documented about 3 decades ago and contained 283 species [14]. Since then, many studies on Mexican freshwaters have reported the presence of 120 additional rotifer taxa. This, however, does not include close to 20 cryptic taxa, which require formal description. From the mean of species estimators, it appears that there is a possibility of encountering more than 600 species in Mexico. This may be a sub-estimation of the actual reality, since it is based on the diversity of rotifers which have been well studied only in 5–7 of the 32 federal entities in the country. This number is not unreasonable if one considers the numerous habitats that exist in Mexico which confer it a megadiverse status (CONABIO), as well as the existence of cryptic taxa within Rotifera. For example, the Brachionus plicatilis complex has as many as 15 cryptic species [45]. Several species complexes have already been reported in Mexico [25,28,29,30]. The geographic location of Mexico (as a corridor between South and North America) [46] also supports the possible occurrence of diverse rotifer species in different federal entities. This is further evidenced by the poor sampling in certain regions, especially in states such as Baja California, Durango, and Coahuila. Mexico has 70 large lakes (area: 1000 to 10,000 hectares), 14,000 reservoirs (85% with <10 hectares), and >200 rivers [6]. The rotifer species list presented in this work was based on only a handful of waterbodies and many more are yet to be studied.

Desert temporary ponds, rivers, and marine ecosystems have great potential for enhancing the species richness of rotifers to the Mexican fauna. For example, ephemeral waterbodies from the desert states in Mexico have yielded more than 100 rotifer species [47]. Yet, many temporary water bodies in Mexico have not been sampled even once. Rotifer fauna in riverine habitats have been rarely studied, although the species richness in these aquatic systems is high [40]. Mexico is bestowed with 9330 km of coastline. Yet, knowledge on the marine rotifers from Mexico is more fragmentary than inland saline waters [48]. For example, seasonal sampling efforts from the brackish water ecosystem in the State of Tabasco showed the presence of more than 35 rotifer species [49]. Of the three classes of rotifers, Bdelloidea, Monogononta, and Seisonacea, the last is represented by two marine genera, Seison and Paraseison. Seison is epizoic on the crustacean genus Nebalia but has not been so far reported from marine waters of Mexico, although Nebalia occurs in these waters [50]. Therefore, further studies on marine rotifers may be oriented for identifying Seison from Nebalia.

An aspect often overlooked in taxonomic studies is the culture of rotifer species, which is important for many reasons. The first is that, when studying the molecular taxonomy of predatory taxa, prey in the stomach contents may interfere with the analysis [26]. The second reason is that culturing species may reveal the presence of different phenotypes from the same genotype as observed in the case of Euchlanis cf. mikropous [51]. Third, some descriptions are vague and incomplete. For example, culturing a rare taxon with appearance of Collotheca monoceros [52] resolved the issue, showing that it was a regeneration by Stephanoceros millsii. Fourth, cryptic species have different life histories which cannot be identified from fixed samples [53]. Finally, for certain analysis of taxonomic characters such as measurements of trophi on SEM, culturing is needed to obtain sufficient quantity for the description of size range [54].

The occurrence of some rotifer species known from the geographic regions such as the Palearctic, Afrotropical, and Oriental were reported from Nearctic region and Neotropical regions of Mexico. For example, Lecane yatseni, typical to the Oriental region, was recorded from Mexico. Similarly, Sphyrias lofauna, common to Afrotropical and Pacific regions, was documented from Nearctic region of Mexico [14]. This suggests not only extensive sampling, but also distributional aspects, including the possible roles that global climatic changes and trade involving aquatic species play a role in the dispersion of rotifers.

5. Conclusions

A taxonomic survey of rotifers so far has revealed the occurrence of about 400 species of rotifers from Mexico. Many Mexican states still do not have formal rotifer checklists. Only a few states in Mexico have some information on the diversity of rotifers. Yet, the species richness reported in this work is based on only a few selected water bodies. Species estimators have predicted the possible occurrence of about 600 rotifer species within the Mexican territory. Thus, further studies are still needed to understand rotifer diversity in Mexico.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d13070291/s1, supplementary 1. List of consulted works for works on rotifer taxonomy and supplementary 2. Database compiled by the authors on the occurrence of different rotifer species from Mexico.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.S.S.; formal analysis, M.A.J.-S.; interpretation, original draft preparation, S.N. All authors have prepared the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PAPIIT-IG 200820.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data were taken from literature and are available from the publishers. Authors will provide data on request.

Acknowledgments

MAJC thanks Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (UNAM) and CONACyT (582568). Three anonymous reviewers have improved our presentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weber, D.; Hintermann, U.; Zangger, A. Scale and trends in species richness: Considerations for monitoring biological diversity for political purposes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2004, 13, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Bousquets, J.; Ocegueda, S. Estado del conocimiento de la biota. In Capital Natural de México. Conocimiento Actual de la Biodiversidad; Conabio: México City, Mexico, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 283–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Albores, J.E.; Badano, E.I.; Flores-Flores, J.; Yáñez-Espinosa, L. Scientific literature on invasive alien species in a megadiverse country: Advances and challenges in Mexico. NeoBiota 2019, 48, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, J.J.; Escalante, T.; Rodríguez-Tapia, G. Mexican biogeographic provinces: Map and shapefiles. Zootaxa 2017, 4277, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.L.; Snell, T.W.; Ricci, C.; Nogrady, T. Rotifera. In Biology, Ecology and Systematics, 2nd ed.; Segers, H., Ed.; Guides to the Identification of the Microinvertebrates of the Continental Waters of the World; Kenobi Productions: Ghent, Belgium; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- De la Lanza, E.G.; García, C.J.L. Lagos y Presas de México; AGT Editor S.A.: México City, Mexico, 2002; p. 680. [Google Scholar]

- Rico-Martínez, R.; Silva-Briano, M. Contribution to the knowledge of the rotifera of Mexico. Hydrobiologia 1993, 255/256, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Martínez, R. Rotíferos. In La Biodiversidad en Aguascalientes: Estudio de Estado; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO): Aguascalientes, Mexico; Instituto del Medio Ambiente del Estado de Aguascalientes (IMAE): Aguascalientes, Mexico; Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes (UAA): Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Serranía-Soto, C.; Nandini, S. Diversidad de Rotíferos. In La Diversidad Biológica del Estado de México; Ceballos, G.R., Ed.; Gobierno del Estado de México y Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO): México, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Páez, M.E.; Zamora-García, M.; Benítez-Díaz-Mirón, M.I.; Mouriño, G.G.; Contreras-Tapia, R.A. Abundancia y biomasa de la comunidad de rotíferos y su relación con parámetros ambientales en tres estaciones del Canal Cuemanco, Xochimilco. Soc. Rural. Prod. Medio Ambiente 2014, 14, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Castro, J.L.; Alvarado-Flores, J.; Uh-Moo, J.C.; Koh-Pasos, C.G. Monogonont rotifers species of the island Cozumel, Quintana Roo, México. Biodivers. Data J. 2019, 7, e34719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Murillo, M.d.R.; Alvarado-Villanueva, R.; Sánchez-Heredia, J.D.; Muñóz-Gaytán, A.A.; Morales, R.H. El Plancton de Agua dulce. In La Biodiversidad en Michoacán; Estudio de Estado 2. CONABIO; Comisión Nacional Para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO): México, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Saucedo, J.J.; Silva-Briano, M.; Sigala-Rodríguez, J.J. Rotíferos. In La Biodiversidad en Zacatecas; Estudio de Estado. CONABIO; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO): México, Mexico; Gobierno del Estado de Zacatecas: México, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, S.S.S. Checklist of rotifers (Rotifera) from Mexico. Environ. Ecol. 1999, 17, 978–983. [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn, D.C.; Allen, M.S.; Bonvechio, K.I.; Hoyer, M.V.; Beesley, L.S. Evaluating estimators of species richness: The importance of considering statistical error rates. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, H. Annotated checklist of the rotifers (Phylum Rotifera), with notes on nomenclature, taxonomy and distribution. Zootaxa 2007, 1564, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jersabek, C.D.; Leitner, M.F. The Rotifer World Catalog. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. 2013. Available online: http://www.rotifera.hausdernatur.at/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Alcántara-Rodríguez, J.A.; Ciros-Pérez, J.; Ortega-Mayagoitia, E.; Serrania-Soto, C.R.; Piedra-Ibarra, E. Local adaptation in populations of a Brachionus group plicatilis cryptic species inhabiting three deep crater lakes in Central Mexico. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.D.; Schröder, T.; Ríos-Arana, J.V.; Rico-Martínez, R.; Silva-Briano, M.; Wallace, R.L.; Walsh, E.J. Patterns of rotifer diversity in the Chihuahuan desert. Diversity 2020, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koste, W. Rotatoria. In Die Rädertiere Mitteleuropas. Ein Bestimmungswerk Begründet von Max Voigt; Bornträger: Stuttgart, Germany, 1978; Volume 1–2, pp. 234, 673. [Google Scholar]

- Segers, H. Rotifera 2: The Lecanidae Monogononta; Guides to the Identification of Microinvertebrates of the Continental Waters of the World Series; Balogh Scientific Books: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.L.; Snell, T.W. Rotifera. Chapter 8. In Ecology and Classifications of North American Freshwater Invertebrates, 3rd ed.; Thorp, J., Covich, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.L.; Snell, T.W.; Walsh, E.J.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Segers, H. Chapter 8. Phylum Rotifera. Keys to Palaearctic Fauna. In Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 219–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K.; Mao, C.X.; Chang, J. Interpolating, extrapolating, and comparing incidence-based species accumulation curves. Ecology 2004, 85, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Morales, A.E.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M. DNA barcoding of freshwater rotifera in Mexico: Evidence of cryptic speciation in common rotifers. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Contreras, J.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Piedra-Ibarra, E.; Calderón-Torres, M.; Nandini, S. Morphological, morphometrical and molecular (CO1 and ITS) analysis of the rotifer Asplanchna brightwellii from selected freshwater bodies in Central Mexico (Mexico). J. Environ. Biol. 2013, 34, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Contreras, J.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Piedra-Ibarra, E.; Nandini, S. Morphometric and molecular (COX 1) variations of Asplanchna girodi clones from Central Mexico. J. Environ. Biol. 2017, 38, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, S.; Peña-Aguado, F.; Arreguin-Rebolledo, U.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Murugan, G. Molecular identity and demographic responses to salinity of a freshwater strain of Brachionus plicatilis from the shallow Lake Pátzcuaro, Mexico. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 2019, 192, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordbacheh, A.; Shapiro, A.N.; Walsh, E.J. Reproductive isolation, morphological and ecological differentiation among cryptic species of Euchlanis dilatata, with the description of four new species. Hydrobiologia 2019, 844, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.J.; Schröder, T.; Wallace, R.L.; Rico-Martínez, R. Cryptic speciation in Lecane bulla (Monogononta: Rotifera) in Chihuahuan Desert waters. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Angew. Limnol. Verh. 2009, 30, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Nandini, S.; Merino-Ibarra, M.; Sarma, S.S.S. Seasonal changes in the zooplankton abundances of the reservoir Valle de Bravo (State of Mexico, Mexico). Lake Reserv. Manag. 2008, 24, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno-Gutiérrez, R.M.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Sobrino-Figueroa, A.S.; Nandini, S. Population growth potential of rotifers from a high altitude eutrophic waterbody, Madín reservoir (State of Mexico, Mexico): The importance of seasonal sampling. J. Limnol. 2018, 77, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Colmenares, M.E.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S. Seasonal variation of rotifers from the high altitude Llano reservoir (State of Mexico, Mexico). J. Environ. Biol. 2017, 38, 1171–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Osnaya-Espinosa, L.R.; Aguilar-Acosta, C.R.; Nandini, S. Seasonal variations in zooplankton abundances in the Iturbide reservoir (Isidro Fabela, State of Mexico, Mexico). J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 32, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Sanchez, M.A.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S. Zooplankton community structure in the presence of low levels of cyanotoxins: A case study in a high altitude tropical reservoir (Valley de Bravo, Mexico). J. Limnol. 2014, 73, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-García, G.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Martínez-Jerónimo, F.; Jiménez-Contreras, J. Impact of chromium and aluminium pollution on the diversity of zooplankton: A case study in the Chimaliapan wetland (Ramsar site) (Lerma basin, Mexico). J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. A 2012, 47, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Contreras, J.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S. Diversity of Rotifera (Monogononta) and egg ratio of selected taxa in the canals of Xochimilco (Mexico City). Wetlands 2018, 38, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S.G.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S. Seasonal variations of rotifers from a high altitude urban shallow water body, La Cantera Oriente (Mexico City, Mexico). Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2017, 35, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Rodríguez, C.A.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S. Zooplankton community changes in relation to different macrophyte species: Effects of Egeria densa removal. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2021, 21, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Gulati, R.D. A seasonal study reveals the occurrence of exotic rotifers in the river Antigua, Veracruz, close to the Gulf of Mexico. River Res. Appl. 2017, 33, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, S.; Ramírez-García, P.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Gutiérrez-Ochoa, R.A. Planktonic indicators of water quality: A case study in the Amacuzac River Basin (State of Morelos, Mexico). River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Sánchez, A.; Reyes-Vanegas, G.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S. Diversity and abundance of rotifers (Rotifera) during an annual cycle in the reservoir Valerio Trujano (Tepecoacuilco, Mexico). Inland Waters 2004, 4, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Morales, E.; Vázquez-Mazy, A.; Solís, M.E. Preliminary investigations on the zooplankton community of a Mexican eutrophic reservoir, a seasonal survey. Hidrobiológica 1993, 3, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-García, P.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Robles-Valderrama, E.; Cuesta, I.; Hurtado-Maria, D. Seasonal variations of zooplankton abundance in the freshwater reservoir Valle de Bravo (Mexico). Hydrobiologia 2002, 467, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.J.; Alcántara-Rodríguez, A.; Ciros-Pérez, J.; Gómez, A.; Hagiwara, A.; Galindo, K.H.; Jersabek, C.D.; Malekzadeh-Viayeh, R.; Leasi, F.; Lee, J.-S.; et al. Fifteen species in one: Deciphering the Brachionus plicatilis species complex (Rotifera, Monogononta) through DNA taxonomy. Hydrobiologia 2017, 796, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; Suárez-Morales, E.; Sarma, S.S.S. Diversity of freshwater zooplankton in the neotropics: The case of Mexico. Verh. Internat. Verein. Limnol. 2001, 27, 4027–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Arana, J.V.; del Carmen Agüero-Reyes, L.; Wallace, R.L.; Walsh, E.J. Limnological characteristics and rotifer community composition of Northern Mexico Chihuahuan desert springs. J. Arid. Environ. 2019, 160, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.J.; Schröder, T.; Wallace, R.L.; Ríos-Arana, J.V.; Rico-Martínez, R. Rotifers from selected inland saline waters in the Chihuahuan Desert of México. Saline Syst. 2008, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S.; Ramírez-García, P.; Cortés-Muñoz, J.E. New records of brackish water Rotifera and Cladocera from Mexico. Hidrobiológica 2000, 10, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Briones, E.; Villalobos-Hiriart, J.L. Nebalia lagartensis (Leptostraca) a new species from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Crustaceana 1995, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S. Adaptive toe morphology of Euchlanis cf. mikropous Koch-Althaus, 1962 (Rotifera: Euchlanidae) exposed directly and indirectly to invertebrate predators. Limnologica 2019, 78, 125693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Jiménez-Santos, M.A.; Nandini, S.; Wallace, R.L. Review on the ecology and taxonomy of sessile rotifers (Rotifera) with special reference to Mexico. J. Environ. Biol. 2020, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldón, C.; Fontaneto, D.; Carmona, M.J.; Montero-Pau, J.; Serra, M. Ecological differentiation in cryptic rotifer species: What we can learn from the Brachionus plicatilis complex. Hydrobiologia 2017, 796, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordbacheh, A.; Wallace, R.L.; Walsh, E.J. Evidence supporting cryptic species within two sessile microinvertebrates, Limnias melicerta and L ceratophylli (Rotifera, Gnesiotrocha). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).