3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)pyridine

Abstract

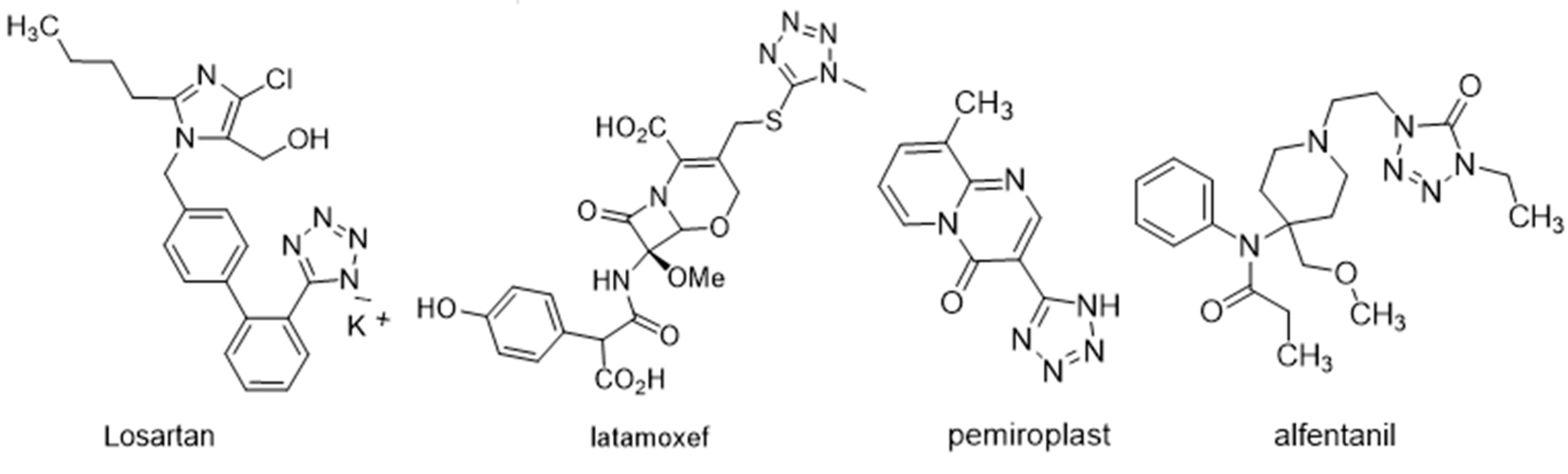

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

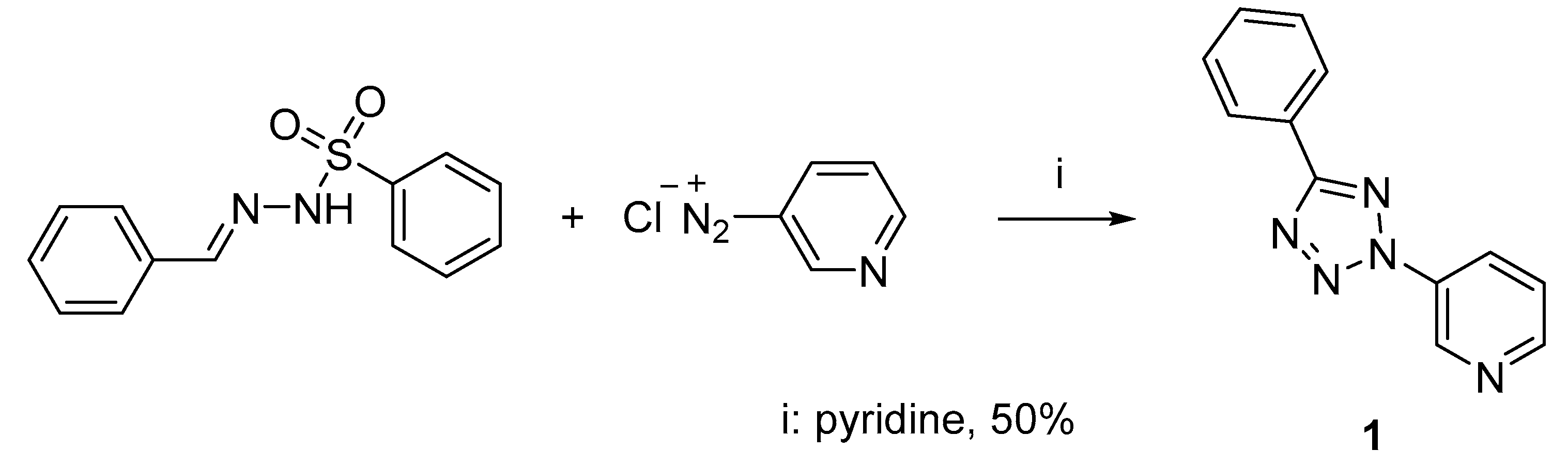

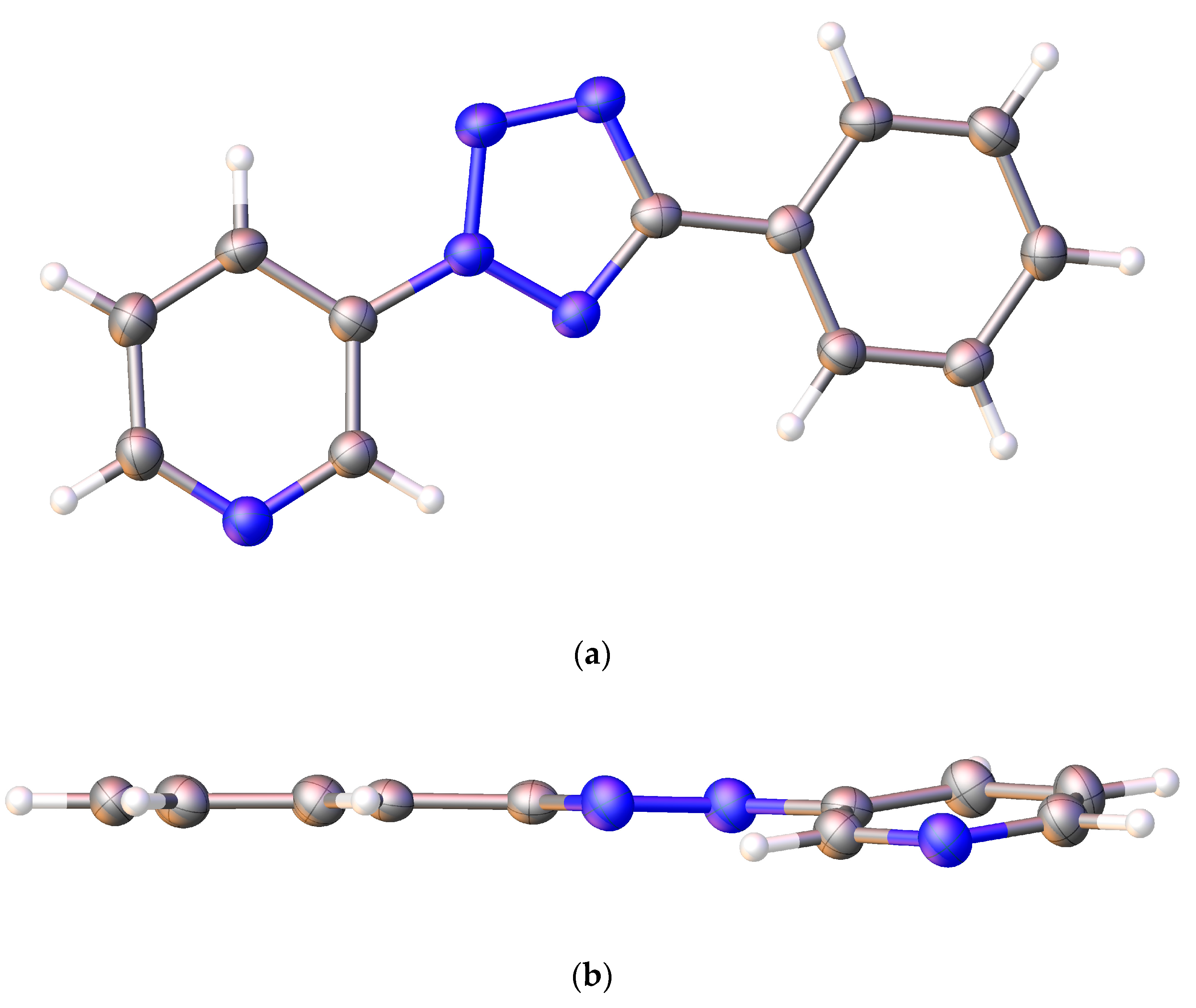

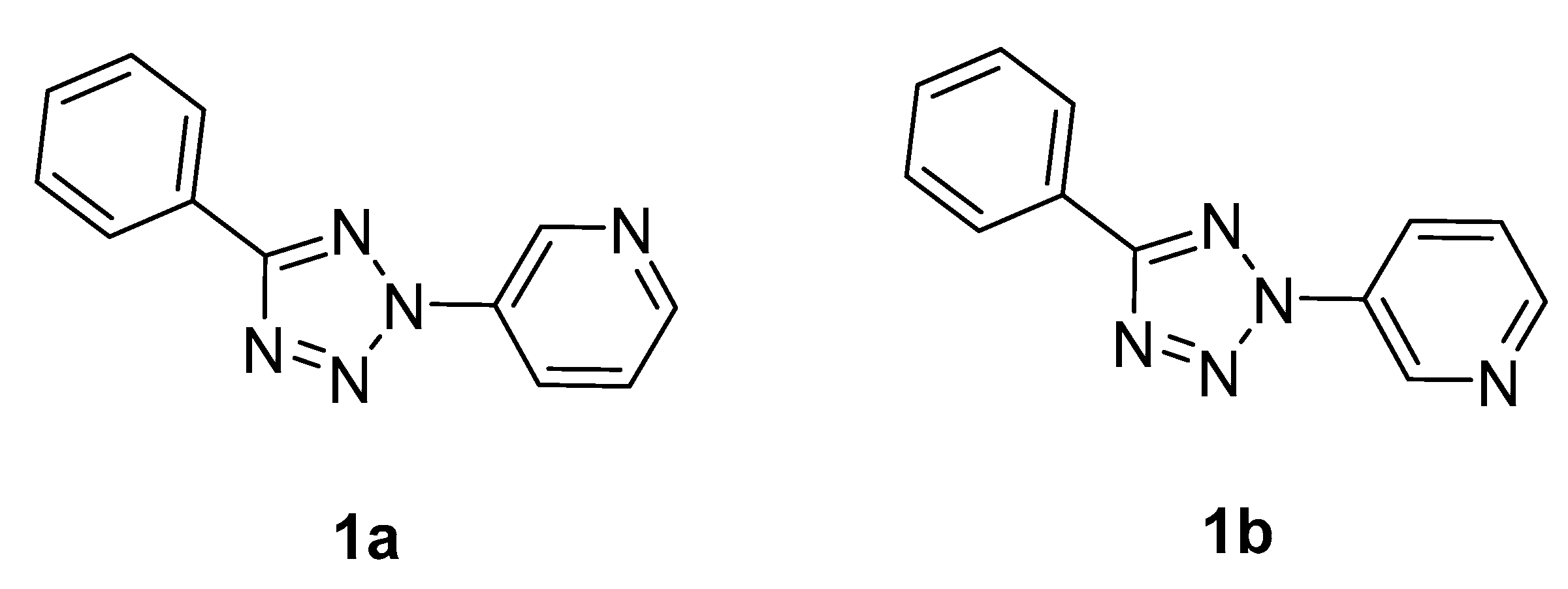

2.1. Synthesis of 3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)pyridine 1

2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

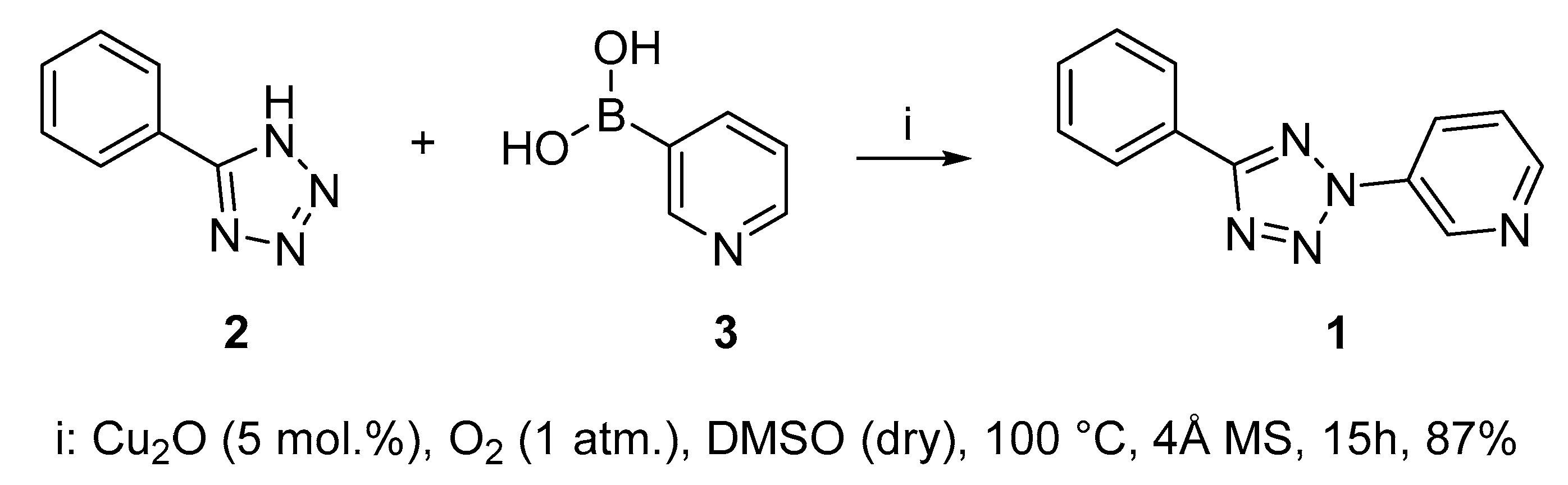

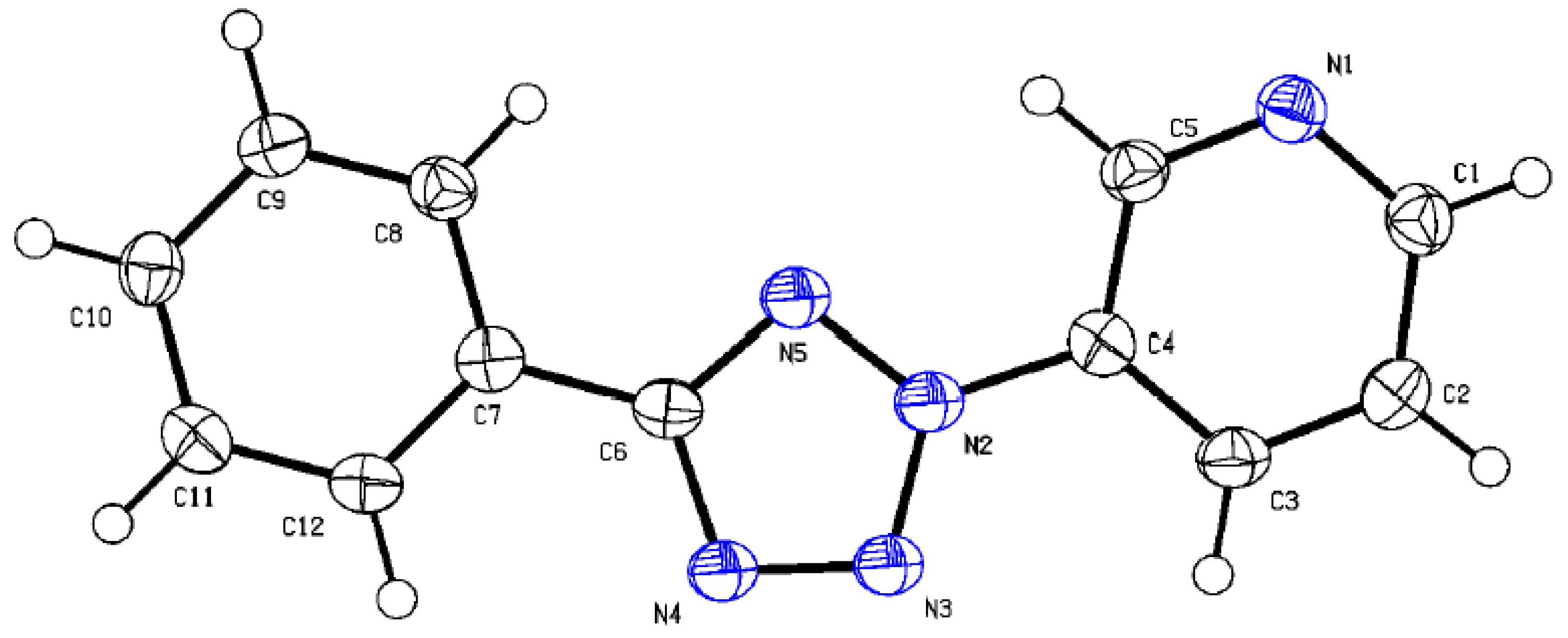

2.3. X-ray Diffraction Analysis and Quantum Chemistry Calculation

2.4. UV–Vis Spectroscopy

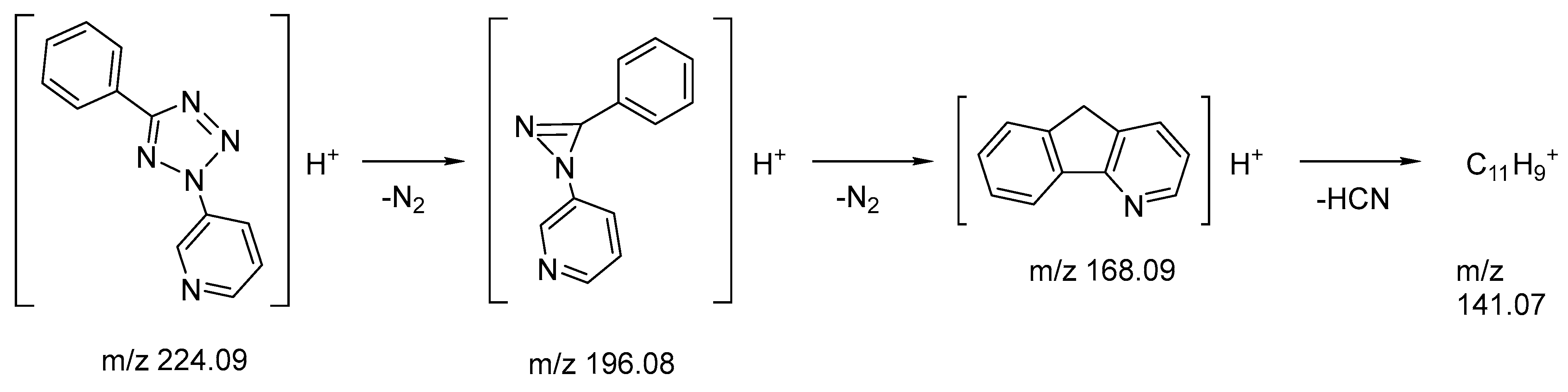

2.5. Mass-Spectrometry

2.6. NMR Spectroscopy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of 3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)-pyridine 1

3.2. Materials and Equipment

3.2.1. Mass-Spectrometry

3.2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.2.3. X-ray Diffraction Analysis

3.2.4. NMR Spectroscopy

3.2.5. IR Spectroscopy

3.2.6. UV–Vis Spectroscopy

3.2.7. Quantum Chemistry Calculation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Ostrovskii, V.A.; Popova, E.A.; Trifonov, R.E. Tetrazoles. In Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Black, D., Cossy, J., Stevens, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; Volume 6, pp. 182–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.A.; Trifonov, R.E.; Ostrovskii, V.A. Tetrazoles for Biomedicine. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2019, 88, 644–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, R.J. 5-Substituted-1H-tetrazoles as Carboxylic Acid Isosteres: Medicinal Chemistry and Synthetic Methods. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 3379–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifonov, R.E.; Ostrovskii, V.A. Protolytic Equilibria in Tetrazoles. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 42, 1585–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the Biological Activity Spectra of Organic Compounds Using the Pass Online Web Resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovskii, V.A.; Danagulyan, G.G.; Nesterova, O.M.; Pavlyukova, Y.N.; Tolstyakov, V.V.; Zarubina, O.S.; Slepukhin, P.A.; Esaulkova, Y.L.; Muryleva, A.A.; Zarubaev, V.V.; et al. Synthesis and antiviral activity of nonannulated tetrazolylpyrimidines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2021, 57, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, E.; Könnecke, A. 2-Aryltetrazoles—Synthese und Eigensehaften. Z. Chem. 1976, 16, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawali, A.S.; Fahmi, A.A.; Eweiss, N.F. Azo Coupling of Benzenesulfonylhydrazones of Heterocyclic Aldehydes. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1979, 16, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beletskaya, I.P.; Davydov, D.V.; Gorovoy, M.S. Palladium- and copper-catalyzed selective arylation of 5-aryltetrazoles by diaryliodonium salts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6221–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.M.T.; Monaco, K.L.; Wang, R.-P.; Winters, M.P. New N- and O-Arylations with Phenylboronic Acids and Cupric Acetate. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 2933–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.A.; Katz, J.L.; West, T.R. Synthesis of Diaryl Ethers through the Copper-Promoted Arylation of Phenols with Arylboronic Acids. An Expedient Synthesis of Thyroxine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 2937–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.Y.; Clark, C.G.; Saubern, S.; Adams, J.; Winters, M.P.; Chan, D.M.; Combs, A. New Aryl/Heteroaryl C-N Bond Cross-coupling Reactions via Arylboronic Acid/Cupric Acetate Arylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 2941–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedinifar, F.; Mahdavi, M.; Rezaei, E.B.; Asadi, M.; Larijani, B. Recent Developments in Arylation of N-Nucleophiles via Chan-Lam Reaction: Updates from 2012 Onwards. Curr. Org. Synth. 2022, 19, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallia, C.J.; Burton, P.M.; Smith, A.M.R.; Walter, G.C.; Baxendale, I.R. Baxendale Ian R. Catalytic Chan–Lam coupling using a ‘tube-in-tube’ reactor to deliver molecular oxygen as an oxidant. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Dong, Z. A Review on the Latest Progress of Chan-Lam Coupling Reaction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 3311–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva Reddy, A.; Ranjith Reddy, K.; Nageswar Rao, D.; Jaladanki, C.K.; Bharatam, P.V.; Lam, P.Y.S.; Das, P. Copper(II)-catalyzed Chan–Lam cross-coupling: Chemoselective N-arylation of aminophenols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vantourout, J.C.; Miras, H.N.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Sproules, S.; Watson, A.J.B. Spectroscopic Studies of the Chan–Lam Amination: A Mechanism-Inspired Solution to Boronic Ester Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4769–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaka, T.; Umemoto, H.; Miki, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Maegawa, T. [Cu(OH)(TMEDA)]2Cl2-Catalyzed Regioselective 2-Arylation of 5-Substituted Tetrazoles with Boronic Acids under Mild Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6703–6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motornov, V.; Latyshev, G.V.; Kotovshchikov, Y.N.; Lukashev, N.V.; Beletskaya, I.P. Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective Chan-Lam N2-Vinylation of 1,2,3-Triazoles and Tetrazoles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 3306–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, J.-Y.; Dong, D.-W.; Han, F.-S. The Development of Copper-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Coupling of NH-Tetrazoles with Boronic Acids and an Insight into the Reaction Mechanism. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 2373–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentrup, C.; Kvaskoff, D. 1,5-(1,7)-Biradicals and Nitrenes Formed by Ring Opening of Hetarylnitrenes. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, C.; Livingstone, K. The Nitrile Imine 1,3-Dipole. In Properties, Reactivity and Applications; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégué, D.; Dargelos, A.; Wentrup, C. Aryl Nitrile Imines and Diazo Compounds. Formation of Indazole, Pyridine N-Imine, and 2-Pyridyldiazomethane from Tetrazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 7952–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrovskii, V.A.; Koldobskii, G.I.; Trifonov, R.E. Tetrazoles. In Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Katritzky, A.R., Ramsden, C.A., Scriven, E.F.V., Taylor, R.J.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN-13: 978-0-0804-4991-3. [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov, R.E.; Alkorta, I.; Ostrovskii, V.A.; Elguero, J. A theoretical study of the tautomerism and ionization of 5-substituted NH-tetrazoles. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2004, 668, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, R.R.; Haque, K.E. Nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectral properties of 5-aryltetrazoles. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 2855–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurukhin, Y.V.; Klyuev, N.A.; Grandberg, I.I. Similarities between thermolysis and mass spectrometric fragmentation of tetrazoles (Review). Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1985, 21, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16; revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dennington, R.D.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, version 6; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Crystal Data | Structure Refinement Parameters |

|---|---|

| CCDC number | 2,237,254 |

| Empirical formula | C12H9N5 |

| Molecular mass | 223.24 |

| Temperature, K | 100(2) |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | I2/a |

| a, Å | 20.8450(9) |

| b, Å | 4.6353(2) |

| c, Å | 22.7163(11) |

| α, ° | 90 |

| β, ° | 107.329(5) |

| γ, ° | 90 |

| Volume, Å3 | 2095.29(17) |

| Z | 8 |

| ρcalc, g/cm3 | 1.415 |

| μ, mm−1 | 0.744 |

| F (000) | 928.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.12 × 0.04 × 0.02 |

| Radiation | Cu Kα (λ = 1.54184) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 8.154 to 138.37 |

| Index ranges | −25 ≤ h ≤ 25, −5 ≤ k ≤ 3, −27 ≤ l ≤ 27 |

| Reflections collected | 7480 |

| Independent reflections | 1949 [Rint = 0.0263, Rsigma = 0.0262] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 1949/0/154 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.064 |

| Final R indices [I ≥ 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0386, wR2 = 0.0966 |

| Final R indices [all data] | R1 = 0.0433, wR2 = 0.0996 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole/e Å−3 | 0.17/−0.18 |

| Rotamer | Basis Set and Solvation Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-311+G(d,p), Gas Phase | aug-cc-pVQZ, Gas Phase | 6-311+G(d,p), Ethanol | |||

| E, au | μ, D | E, au | μ, D | E, au | |

| 1a | −736.38507 | 0.34 | −736.71644 | 0.33 | −736.39514 |

| 1b | −736.38479 | 3.83 | −736.71618 | 3.68 | −736.39508 |

| ΔE *. kcal/mol | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.04 | ||

| Parameter | X-ray, exp. | DFT B3LYP, Calculated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-311+G(d,p) Gas Phase | 6-311+G(d,p) Ethanol | aug-cc-pVQZ Gas Phase | ||

| Bond lengths, angstroms | ||||

| N1–C1 | 1.344 | 1.336 | 1.338 | 1.332 |

| C5–N1 | 1.336 | 1.333 | 1.335 | 1.329 |

| N2–C4 | 1.424 | 1.421 | 1.423 | 1.417 |

| N2–N3 | 1.337 | 1.337 | 1.333 | 1.331 |

| N3–N4 | 1.315 | 1.299 | 1.303 | 1.296 |

| N4–C6 | 1.363 | 1.366 | 1.365 | 1.362 |

| C6–N5 | 1.331 | 1.331 | 1.331 | 1.327 |

| N5–N2 | 1.337 | 1.332 | 1.331 | 1.328 |

| C7–C6 | 1.461 | 1.465 | 1.466 | 1.462 |

| Bond angles, degrees | ||||

| N2–C4–C5 | 119.5 | 120.0 | 119.8 | 120.1 |

| C3–C4–N2 | 120.4 | 120.3 | 120.4 | 120.3 |

| N3–N2–C4 | 122.7 | 123.0 | 123.1 | 120.0 |

| Torsion angles, degrees | ||||

| C8–C7–C6–N5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N3–N2–C4–C3 | 11.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MSn | Precursor Ions | Fragments Accurate Mass (Intensity, %) | Best Possible Ion Formulae | Error in ppm | Possible Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS1 | – | 224.09325 (10) | C12H10N5+ | 0.795 | [M + H]+ |

| MS1 | – | 196.08716 (100) | C12H10N3+ | 1.204 | [M + H–N2]+ |

| MS2 | 196.08716 | 168.08091 (100) | C12H10N+ | 0.798 | [M + H–2N2]+ |

| MS2 | 196.08716 | 141.0699 (2) | C11H9+ | 0.164 | [M + H–2N2–HCN]+ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ershov, I.S.; Esikov, K.A.; Nesterova, O.M.; Skryl’nikova, M.A.; Khramchikhin, A.V.; Shmaneva, N.T.; Chernov, I.S.; Chernova, E.N.; Puzyk, A.M.; Sivtsov, E.V.; et al. 3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)pyridine. Molbank 2023, 2023, M1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1598

Ershov IS, Esikov KA, Nesterova OM, Skryl’nikova MA, Khramchikhin AV, Shmaneva NT, Chernov IS, Chernova EN, Puzyk AM, Sivtsov EV, et al. 3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)pyridine. Molbank. 2023; 2023(1):M1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1598

Chicago/Turabian StyleErshov, Ivan S., Kirill A. Esikov, Olga M. Nesterova, Mariya A. Skryl’nikova, Andrey V. Khramchikhin, Nadezda T. Shmaneva, Ivan S. Chernov, Ekaterina N. Chernova, Aleksandra M. Puzyk, Eugene V. Sivtsov, and et al. 2023. "3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)pyridine" Molbank 2023, no. 1: M1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1598

APA StyleErshov, I. S., Esikov, K. A., Nesterova, O. M., Skryl’nikova, M. A., Khramchikhin, A. V., Shmaneva, N. T., Chernov, I. S., Chernova, E. N., Puzyk, A. M., Sivtsov, E. V., Pavlyukova, Y. N., Trifonov, R. E., & Ostrovskii, V. A. (2023). 3-(5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)pyridine. Molbank, 2023(1), M1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1598