Dimethyl 2-{[2-(2-Methoxy-1-methoxycarbonyl-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,7-trimethoxy-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl]methyl}malonate

Abstract

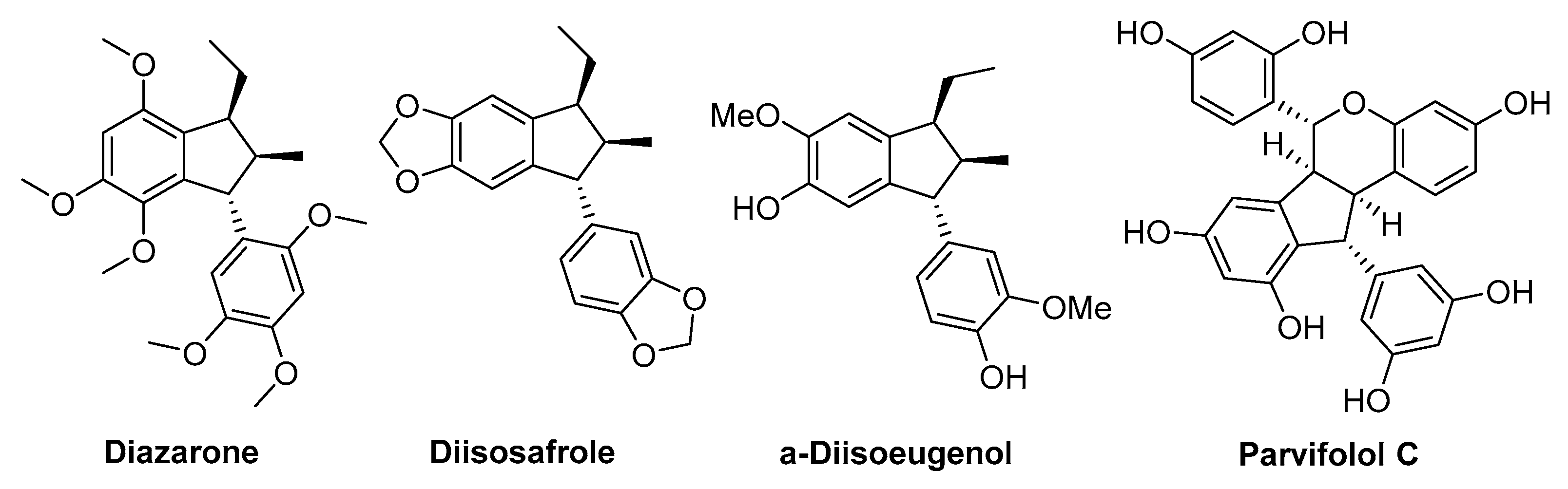

1. Introduction

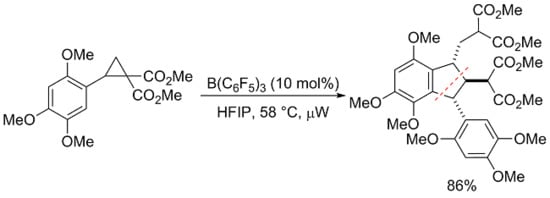

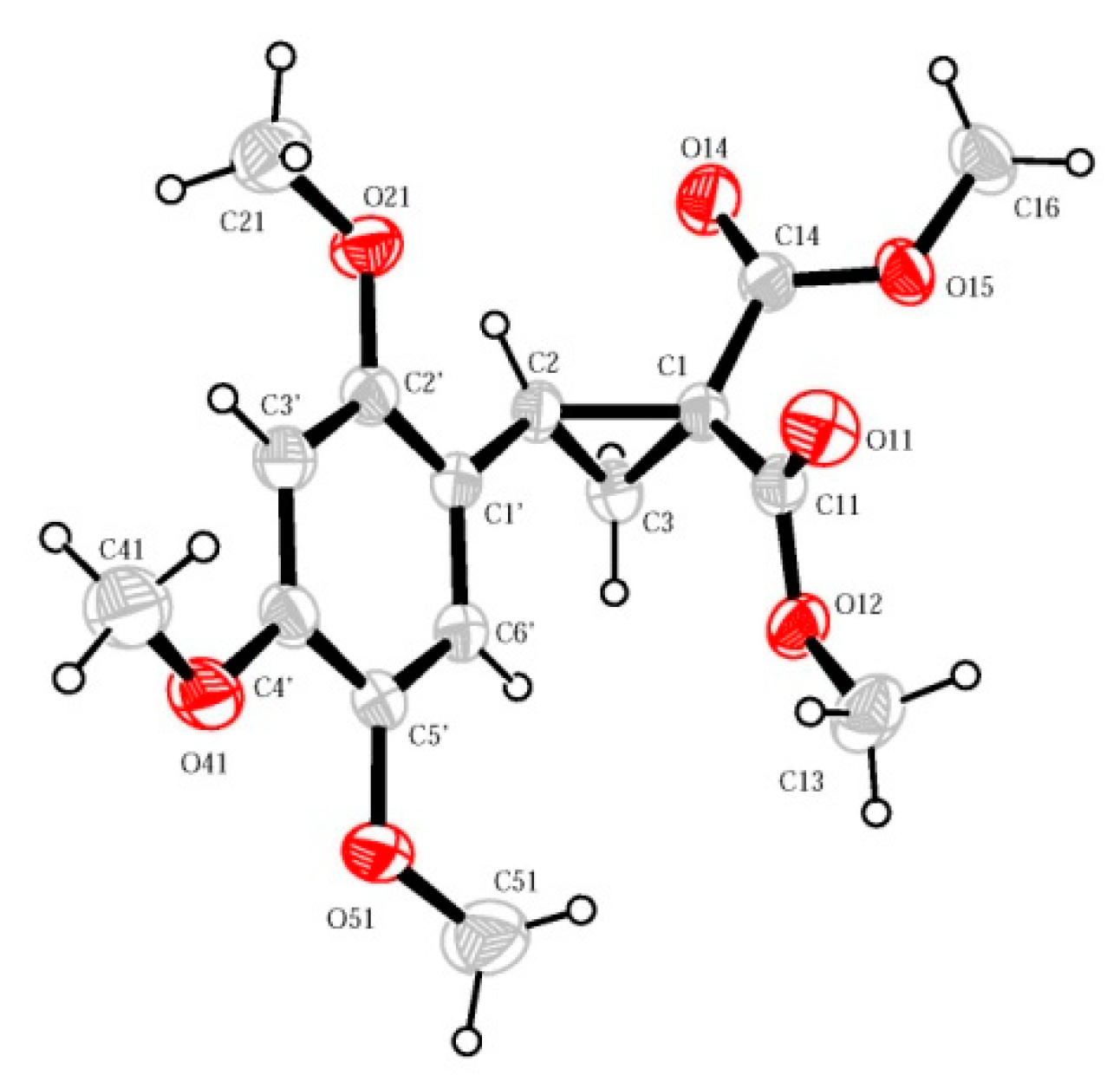

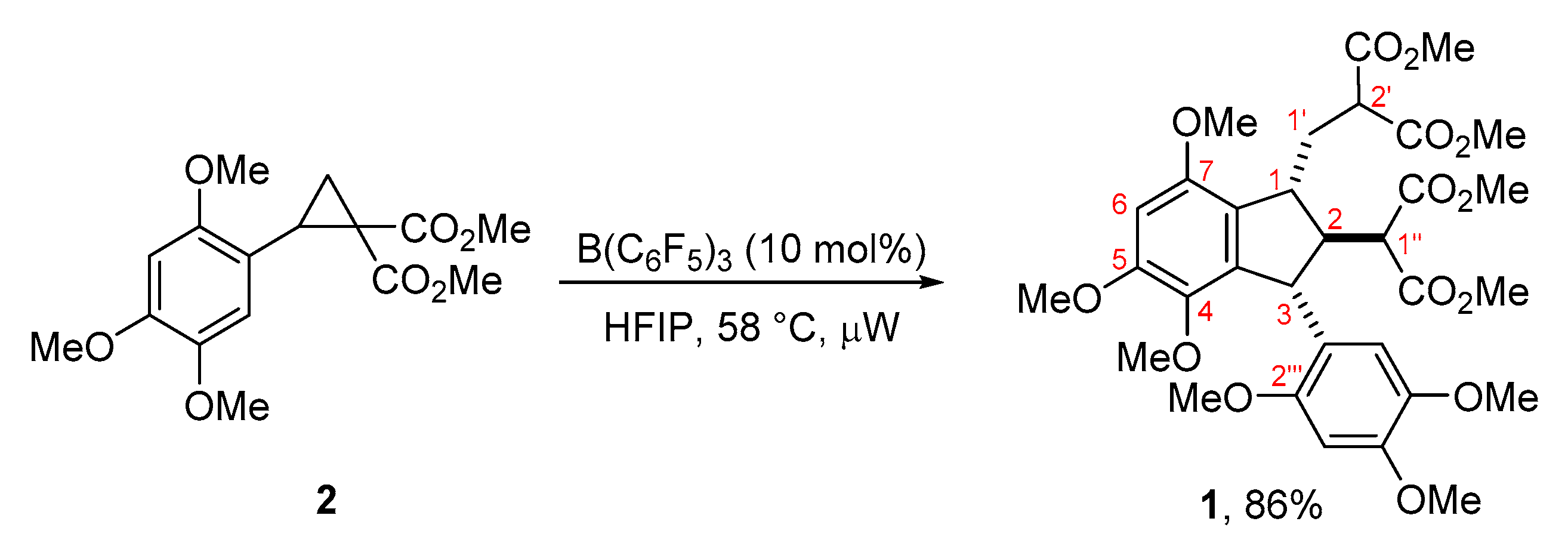

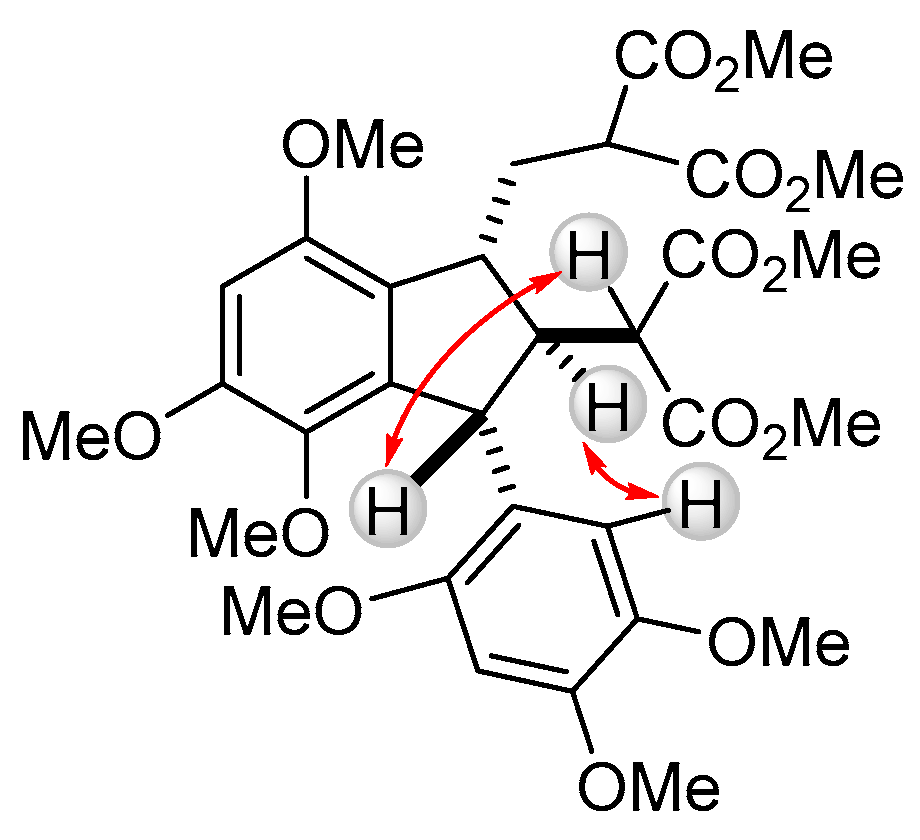

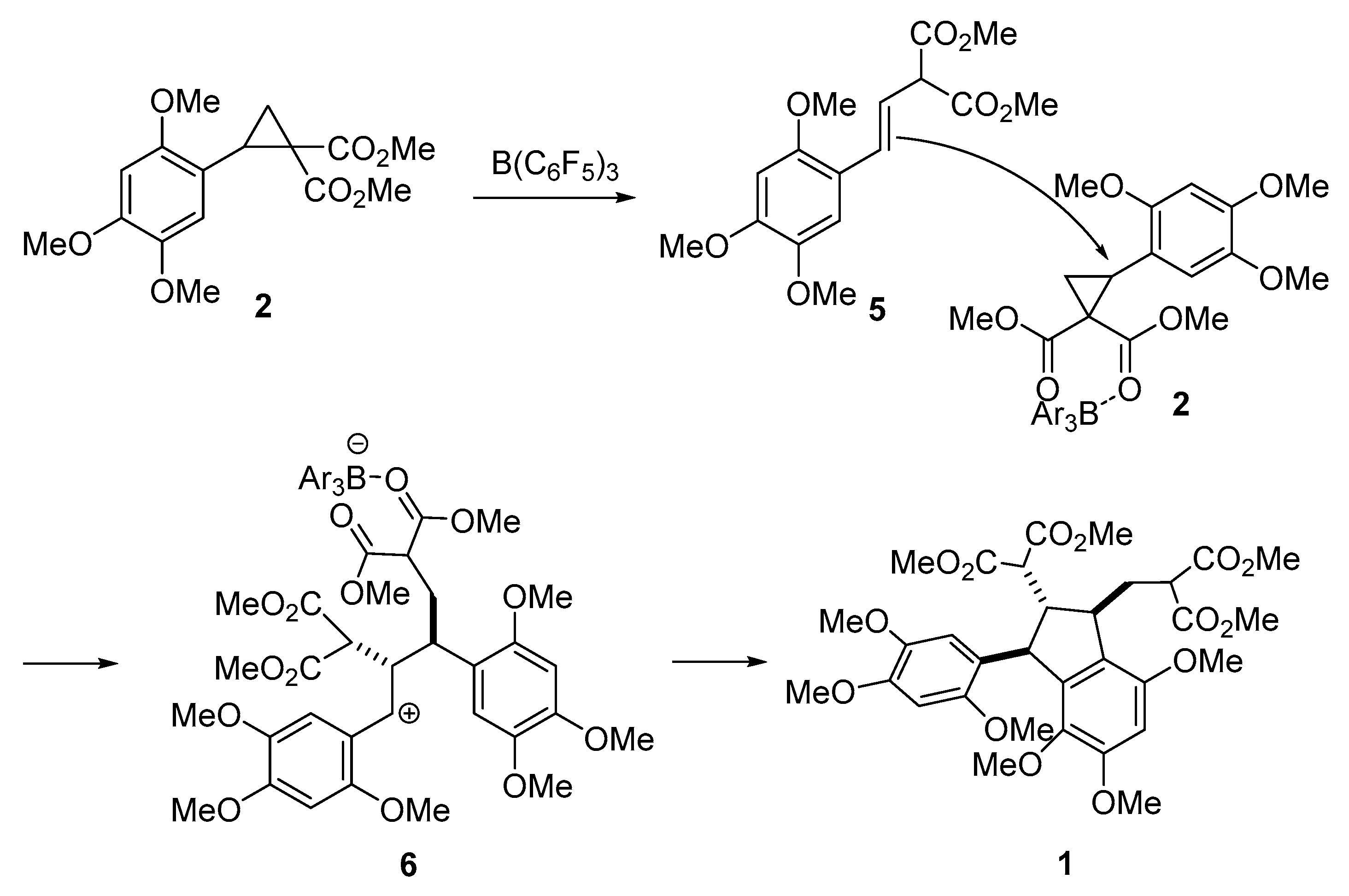

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

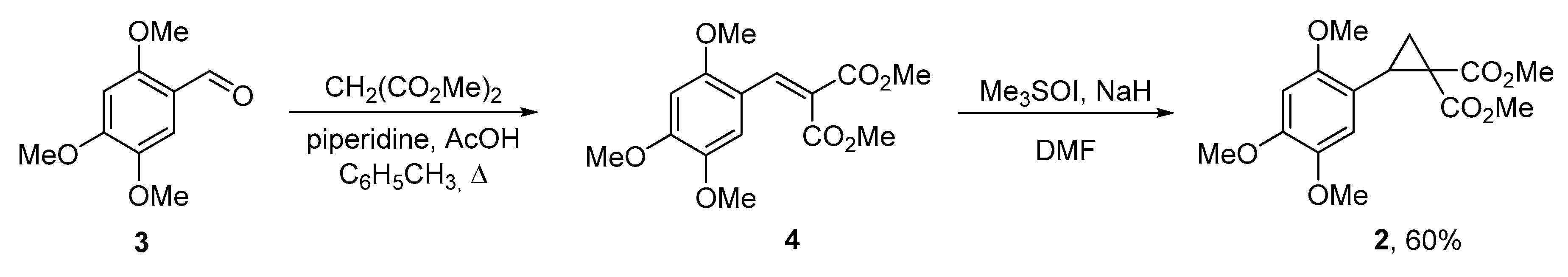

3.1. Dimethyl 2-(2,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)malonate (4)

3.2. Dimethyl 2-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)cyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxylate (2)

3.3. Dimethyl 2-{[2-(2-methoxy-1-methoxycarbonyl-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,7-trimethoxy-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl]methyl}malonate (1) (as a Mixture of (1RS,2RS,3RS)- and (1RS,2SR,3SR)–isomers in 84:16 Ratio)

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Werz, D.B.; Biju, A.T. Uncovering the Neglected Similarities of Arynes and Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.F.; Kaschel, J.; Werz, D.B. A New Golden Age for Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5504–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budynina, E.M.; Ivanov, K.L.; Sorokin, I.D.; Melnikov, M.Y. Ring Opening of Donor-Acceptor Cyclopropanes with N-Nucleophiles. Synthesis 2017, 49, 3035–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Trushkov, I.V. Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes in the Synthesis of Carbocycles. Chem. Rec. 2019, 19, 2189–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Tomilov, Y.V. Dimerization of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Mendeleev Commun. 2015, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mel’nikov, M.Y.; Budynina, E.M.; Ivanova, O.A.; Trushkov, I.V. Recent advances in ring-forming reactions of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Mendeleev Commun. 2011, 21, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Skvortsov, D.A.; Trushkov, I.V.; Melnikov, M.Y. A Straightforward Approach to Tetrahydroindolo[3,2-b]carbazoles and 1-Indolyltetrahydrocarbazoles through [3+3] Cyclodimerization of Indole-Derived Cyclopropanes. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Chagarovskiy, A.O.; Trushkov, I.V.; Melnikov, M.Y. (3 + 3)-Cyclodimerization of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes. Three Routes to Six-Membered Rings. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 8852–8868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Korolev, V.A.; Timofeev, V.P.; Tomilov, Y.V. New dimerization and cascade oligomerization reactions of dimethyl 2-phenylcyclopropan-1,1-dicarboxylate catalyzed by Lewis acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4996–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Tomilov, Y.V. Dimerization of Dimethyl 2-(Naphthalen-1-yl)cyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxylate in the Presence of GaCl3 to [3+2], [3+3], [3+4], and Spiroannulation Products. Helv. Chim. Acta 2013, 96, 2068–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Trushkov, I.V.; Melnikov, M.Y. New domino dimerization of cyclopropylindoles: Synthesis of 1,3-bis(indolyl)cyclopentanes. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2015, 51, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Skvortsov, D.A.; Trushkov, I.V.; Melnikov, M.Y. Shortcut Approach to Cyclopenta[b]indoles by [3+2] Cyclodimerization of Indole-Derived Cyclopropanes. Synlett 2014, 25, 2289–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Skvortsov, D.A.; Limoge, M.; Bakin, A.V.; Chagarovskiy, A.O.; Trushkov, I.V.; Melnikov, M.Y. A bioinspired route to indanes and cyclopentannulated hetarenes via (3+2)-cyclodimerization of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11482–11484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagarovskiy, A.O.; Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Trushkov, I.V.; Melnikov, M.Y. [3+2] Cyclodimerization of 2-arylcyclopropane-1,1-diesters. Lewis acid induced reversion of cyclopropane umpolung. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4421–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Tarasova, A.V.; Denisov, D.A.; Korolev, V.A.; Tomilov, Y.V. Cascade Dimerization of 2-styryl-1,1-cyclopropanedicarboxylate upon treatment with gallium trichloride. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2016, 65, 2628–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Tarasova, A.V.; Korolev, V.A.; Timofeev, V.P.; Tomilov, Y.V. A New Type of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropane Reactivity: The Generation of Formal 1,2- and 1,4-Dipoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3187–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Tarasova, A.V.; Tomilov, Y.V. Synthesis of substituted naphthalenes by GaCl3-mediated cross-dimerization–fragmentation of 2-arylcyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxylates. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2014, 63, 2737–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Tarasova, A.V.; Suponitsky, K.Y.; Tomilov, Y.V. Unexpected formation of substituted naphthalenes and phenanthrenes in a GaCl3 mediated dimerization–fragmentation reaction of 2-arylcyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxylates. Mendeleev Commun. 2014, 24, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, R.A.; Timofeev, V.P.; Tomilov, Y.V. Stereoselective Double Lewis Acid/Organo-Catalyzed Dimerization of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes into Substituted 2-Oxabicyclo[3.3.0]octanes. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 5993–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.A.; Budynina, E.M.; Chagarovskiy, A.O.; Rakhmankulov, E.R.; Trushkov, I.V.; Semeykin, A.V.; Shimanovskii, N.L.; Melnikov, M.Y. Domino Cyclodimerization of Indole-Derived Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes: One-Step Construction of the Pentaleno[1,6a-b]indole Skeleton. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 11738–11742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, T.; Murakami, Y.; Shibuya, K.; Tonosaki, K.; Fujisawa, S. Induction of Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis and Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Gene Expression, by Curcumin and its Analog, α-Diisoeugenol. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 4029–4036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohyama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Ito, T.; Iinuma, M.; Bastow, K.F.; Lee, K.-H. Antitumor agents 200. Cytotoxicity of naturally occurring resveratrol oligomers and their acetate derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 3057–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Han, X.H.; Hong, S.S.; Lee, C.; Choe, S.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y.; Hong, J.T.; Lee, M.K.; Hwang, B.Y. Antioxidative oligostilbenes from Caragana sinica. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Wu, B.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, L. Stilbene Oligomers from Parthenocissus laetevirens: Isolation, Biomimetic Synthesis, Absolute Configuration, and Implication of Antioxidative Defense System in the Plant. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5233–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Ma, X.; Song, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, H. Two New Resveratrol Tetramers Isolated from Cayratia japonica (Thunb.) Gagn. with Strong Inhibitory Activity on Fatty Acid Synthase and Antioxidant Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 2931–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T.; Xu, F.; Matsuda, H.; Yoshikawa, M. Structures of Novel Norstilbene Dimer, Longusone A, and Three New Stilbene Dimers, Longusols A, B, and C, with Antiallergic and Radical Scavenging Activities from Egyptian Natural Medicine Cyperus longus. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavaud, A.; Soleti, R.; Hay, A.-E.; Richomme, P.; Guilet, D.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Paradoxical effects of polyphenolic compounds from Clusiaceae on angiogenesis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buev, E.M.; Moshkin, V.S.; Sosnovskikh, V.Y. Spiroanthraceneoxazolidine as a synthetic equivalent of methanimine in the reaction with donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Synthesis of diethyl 5-arylpyrrolidine-3,3-dicarboxylates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3731–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichenko, M.A.; Chagarovskiy, A.O.; Rybakov, V.B.; Trushkov, I.V.; Ivanova, O.A. CCDC 1972617: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination. CSD Commun. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, A.; Lücht, A.; Grunenberg, J.; Jones, P.G.; Werz, D.B. Kinetic Studies of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes: The Influence of Structural and Electronic Properties on the Reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1955–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.-S.; Zhao, G.-F.; Qin, T.; Suo, Y.-B.; Qu, G.-R.; Guo, H.-M. Thiourea participation in [3+2] cycloaddition with donor–acceptor cyclopropanes: A domino process to 2-amino-dihydrothiophenes. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 1580–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailov, A.A.; Dilman, A.D.; Novikov, R.A.; Khotoshutina, Y.A.; Struchkova, M.I.; Arkhipov, D.E.; Nelyubina, Y.V.; Tabolin, A.A.; Ioffe, S.L. Tandem Pd-catalyzed C–C coupling/recyclization of 2-(2-bromoaryl)cyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxylates with primary nitro alkanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. ORTEP-3 for Windows—A version of ORTEP-III with a Graphical User Interface (GUI). J. Appl. Cryst. 1997, 30, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piers, W.E.; Chivers, T. Pentafluorophenylboranes: From obscurity to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 26, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boichenko, M.A.; Chagarovskiy, A.O.; Rybakov, V.B.; Trushkov, I.V.; Ivanova, O.A. Dimethyl 2-{[2-(2-Methoxy-1-methoxycarbonyl-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,7-trimethoxy-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl]methyl}malonate. Molbank 2020, 2020, M1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1107

Boichenko MA, Chagarovskiy AO, Rybakov VB, Trushkov IV, Ivanova OA. Dimethyl 2-{[2-(2-Methoxy-1-methoxycarbonyl-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,7-trimethoxy-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl]methyl}malonate. Molbank. 2020; 2020(1):M1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1107

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoichenko, Maksim A., Alexey O. Chagarovskiy, Victor B. Rybakov, Igor V. Trushkov, and Olga A. Ivanova. 2020. "Dimethyl 2-{[2-(2-Methoxy-1-methoxycarbonyl-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,7-trimethoxy-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl]methyl}malonate" Molbank 2020, no. 1: M1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1107

APA StyleBoichenko, M. A., Chagarovskiy, A. O., Rybakov, V. B., Trushkov, I. V., & Ivanova, O. A. (2020). Dimethyl 2-{[2-(2-Methoxy-1-methoxycarbonyl-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,7-trimethoxy-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl]methyl}malonate. Molbank, 2020(1), M1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/M1107