Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility and Chemosensitivity to KRAS Modulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Morphological and Chemo-Responsive Changes with KRAS Downregulation

2.1.1. CRISPR-Based Gene Editing

2.1.2. Dose-Dependent Transcriptional Regulation of KRAS (Tet-ON System)

2.1.3. Promoter-Targeting PPRH Oligonucleotides

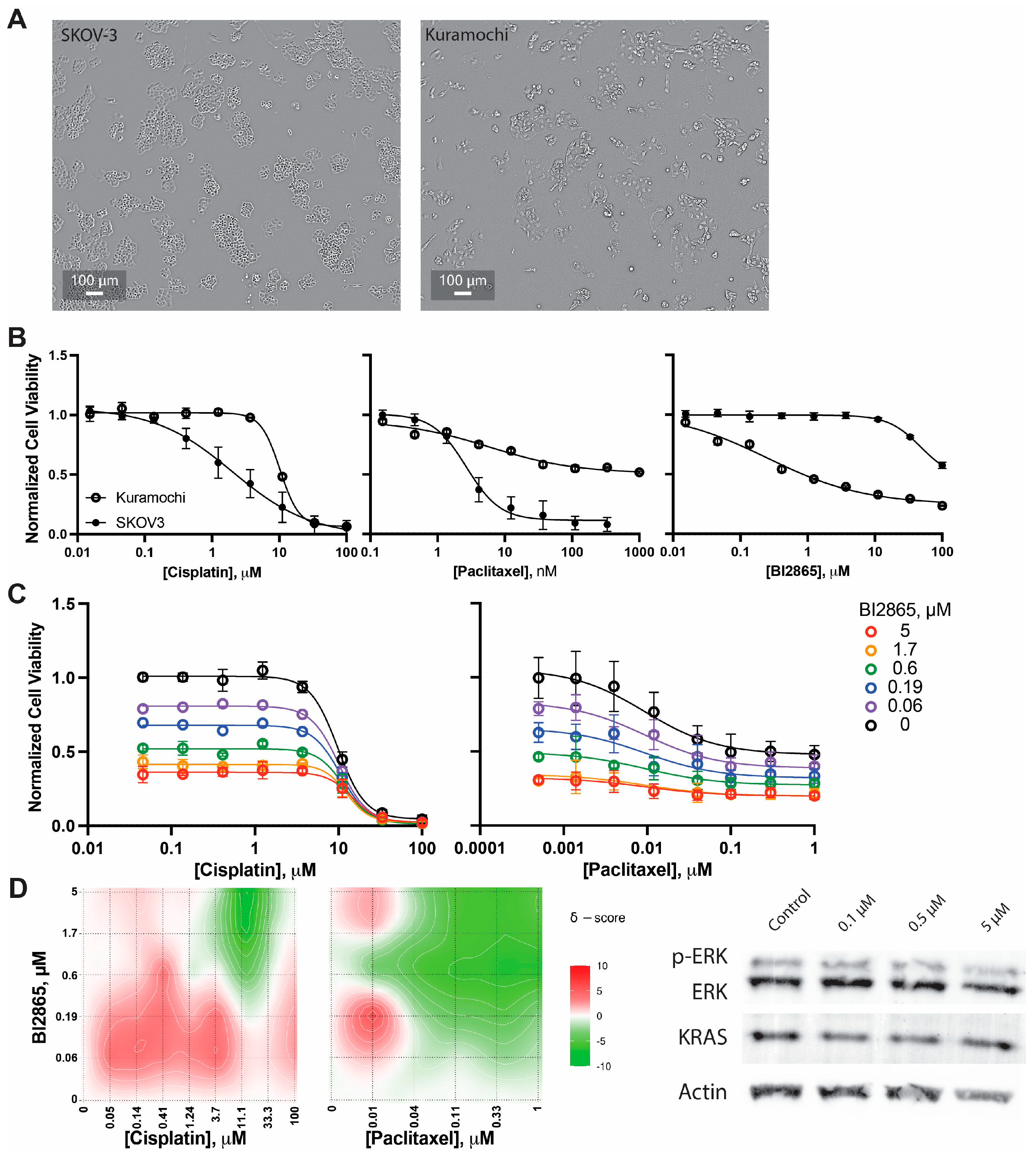

2.2. Enhanced Paclitaxel Efficacy with Pharmacologic KRAS Inhibition

2.2.1. KRAS Inhibitors

2.2.2. Validation in High-Grade Serous Kuramochi Ovarian Cancer Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals, Oligonucleotides and Plasmids

4.2. Plasmid Construction

4.3. Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

4.4. Derivative Cell Line Generation and Confirmation

4.5. qPCR

4.6. Cellular Viability Mono- and Combination Therapies

4.7. Statistical Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| 3D | 3-dimensional, non-adherent |

| 2D | 2-dimensional, adherent |

| gDNA | Guide RNA |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| Cas9 | CRISPR-associated protein 9 |

| PPRH | Polypurine Reverse Hoogsteen |

| Tet-ON | Tetracycline-inducible gene expression system |

| PROTAC | Proteolysis-targeting chimera |

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma |

| DOTAP | 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhriyal, R.; Hariprasad, R.; Kumar, L.; Hariprasad, G. Chemotherapy Resistance in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients. Biomark. Cancer 2019, 11, 1179299X19860815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polajžer, S.; Černe, K. Precision Medicine in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Targeted Therapies and the Challenge of Chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.B.; Kim, H.; Rafail, S.; Omran, D.K.; Medvedev, S.; Kinose, Y.; Rodriguez-Garcia, A.; Flowers, A.J.; Xu, H.; Schwartz, L.E.; et al. An Autologous Humanized Patient-Derived-Xenograft Platform to Evaluate Immunotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.L.; Eskander, R.N.; O’Malley, D.M. Advances in Ovarian Cancer Care and Unmet Treatment Needs for Patients with Platinum Resistance: A Narrative Review. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.T.; Nakayama, K.; Rahman, M.; Katagiri, H.; Katagiri, A.; Ishibashi, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Sato, E.; Iida, K.; Nakayama, N.; et al. KRAS and MAPK1 Gene Amplification in Type II Ovarian Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 13748–13762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkeland, E.; Wik, E.; Mjøs, S.; Hoivik, E.A.; Trovik, J.; Werner, H.M.J.; Kusonmano, K.; Petersen, K.; Raeder, M.B.; Holst, F.; et al. KRAS Gene Amplification and Overexpression but Not Mutation Associates with Aggressive and Metastatic Endometrial Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, A.A. Blocking Oncogenic Ras Signaling for Cancer Therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colicelli, J. Human RAS Superfamily Proteins and Related GTPases. Sci. STKE Signal Transduct. Knowl. Environ. 2004, 2004, RE13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Lyons, J.; Miller, A.L.; Phan, V.T.; Alarcón, I.R.; McCormick, F. Ras Signaling and Therapies. Adv. Cancer Res. 2009, 102, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friday, B.B.; Adjei, A.A. K-Ras as a Target for Cancer Therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1756, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Petricoin, E.F.; Maitra, A.; Rajapakse, V.; King, C.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Ross, S.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D.; Hitt, B.A.; et al. Preinvasive and Invasive Ductal Pancreatic Cancer and Its Early Detection in the Mouse. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therachiyil, L.; Anand, A.; Azmi, A.; Bhat, A.; Korashy, H.M.; Uddin, S. Role of RAS Signaling in Ovarian Cancer. F1000Research 2022, 11, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timar, J.; Kashofer, K. Molecular Epidemiology and Diagnostics of KRAS Mutations in Human Cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasimli, K.; Raab, M.; Tahmasbi Rad, M.; Kurunci-Csacsko, E.; Becker, S.; Strebhardt, K.; Sanhaji, M. Sequential Targeting of PLK1 and PARP1 Reverses the Resistance to PARP Inhibitors and Enhances Platin-Based Chemotherapy in BRCA-Deficient High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer with KRAS Amplification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, E.K.; Lambert, I.H. Ion Channels and Transporters in the Development of Drug Resistance in Cancer Cells. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holohan, C.; Van Schaeybroeck, S.; Longley, D.B.; Johnston, P.G. Cancer Drug Resistance: An Evolving Paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, E.C.; Drezner, N.; Li, X.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Bi, Y.; Liu, J.; Rahman, A.; Wearne, E.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Sotorasib for KRAS G12C-Mutated Metastatic NSCLC. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.X.; Arter, Z.L. Adagrasib in KRYSTAL-12 Has Broken the KRAS G12C Enigma Code in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2024, 15, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, L.; Zuo, X.; Maitra, A.; Bresalier, R.S. A Small Molecule with Big Impact: MRTX1133 Targets the KRASG12D Mutation in Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Herdeis, L.; Rudolph, D.; Zhao, Y.; Böttcher, J.; Vides, A.; Ayala-Santos, C.I.; Pourfarjam, Y.; Cuevas-Navarro, A.; Xue, J.Y.; et al. Pan-KRAS Inhibitor Disables Oncogenic Signalling and Tumour Growth. Nature 2023, 619, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popow, J.; Farnaby, W.; Gollner, A.; Kofink, C.; Fischer, G.; Wurm, M.; Zollman, D.; Wijaya, A.; Mischerikow, N.; Hasenoehrl, C.; et al. Targeting Cancer with Small-Molecule Pan-KRAS Degraders. Science 2024, 385, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaras, A.M.; Valiuska, S.; Noé, V.; Ciudad, C.J.; Brooks, T.A. Targeting KRAS Regulation with PolyPurine Reverse Hoogsteen Oligonucleotides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; To, K.K.W.; Hu, G.; Fu, K.; Yang, C.; Zhu, S.; Pan, C.; Wang, F.; Luo, K.; Fu, L. BI-2865, a Pan-KRAS Inhibitor, Reverses the P-Glycoprotein Induced Multidrug Resistance in Vitro and in Vivo. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, A.; Schischlik, F.; Rocchetti, F.; Popow, J.; Ebner, F.; Gerlach, D.; Geyer, A.; Santoro, V.; Boghossian, A.S.; Rees, M.G.; et al. Pan-KRAS Inhibitors BI-2493 and BI-2865 Display Potent Antitumor Activity in Tumors with KRAS Wild-Type Allele Amplification. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Xiao, X.; Xia, X.; Min, J.; Tang, W.; Shi, X.; Xu, K.; Zhou, G.; Li, K.; Shen, P.; et al. A Pan-KRAS Inhibitor and Its Derived Degrader Elicit Multifaceted Anti-Tumor Efficacy in KRAS-Driven Cancers. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1866–1884.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisio, M.-A.; Fu, L.; Goyeneche, A.; Gao, Z.-H.; Telleria, C. High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Basic Sciences, Clinical and Therapeutic Standpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domcke, S.; Sinha, R.; Levine, D.A.; Sander, C.; Schultz, N. Evaluating Cell Lines as Tumour Models by Comparison of Genomic Profiles. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, K.M.; Emori, M.M.; Papp, E.; MacDuffie, E.; Konecny, G.E.; Velculescu, V.E.; Drapkin, R. Beyond Genomics: Critical Evaluation of Cell Line Utility for Ovarian Cancer Research. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cell Line—KRAS—The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000133703-KRAS/cell+line (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Gallego-Jara, J.; Lozano-Terol, G.; Sola-Martínez, R.A.; Cánovas-Díaz, M.; de Diego Puente, T. A Compressive Review about Taxol®: History and Future Challenges. Molecules 2020, 25, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK Pathway for Cancer Therapy: From Mechanism to Clinical Studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysova, M.K.; Cui, Y.; Snyder, M.; Guadagno, T.M. Knockdown of B-Raf Impairs Spindle Formation and the Mitotic Checkpoint in Human Somatic Cells. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2894–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttrick, G.J.; Wakefield, J.G. PI3-K and GSK-3: Akt-Ing Together with Microtubules. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2621–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, C. Let-7 Sensitizes KRAS Mutant Tumor Cells to Chemotherapy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, Y.M.; Cross, R.A. Taxol Acts Differently on Different Tubulin Isotypes. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.H.A.; Wu, S.-Y.; Lee, T.-R.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wu, J.-S.; Hsieh, H.-P.; Chang, J.-Y. Cancer Cells Acquire Mitotic Drug Resistance Properties through Beta I-Tubulin Mutations and Alterations in the Expression of Beta-Tubulin Isotypes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKeigan, J.P.; Taxman, D.J.; Hunter, D.; Earp, H.S.; Graves, L.M.; Ting, J.P.-Y. Inactivation of the Antiapoptotic Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-Akt Pathway by the Combined Treatment of Taxol and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, J.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y. PI3K/AKT Pathway as a Key Link Modulates the Multidrug Resistance of Cancers. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascio, F.; Spadaccino, F.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Castellano, G.; Stallone, G.; Netti, G.S.; Ranieri, E. The Pathogenic Role of PI3K/AKT Pathway in Cancer Onset and Drug Resistance: An Updated Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, A.C.; Silva, P.M.A.; Sarmento, B.; Bousbaa, H. Antagonizing the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Silencing Enhances Paclitaxel and Navitoclax-Mediated Apoptosis with Distinct Mechanistic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, M.R. MAP Kinase Meets Mitosis: A Role for Raf Kinase Inhibitory Protein in Spindle Checkpoint Regulation. Cell Div. 2007, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, W.P.; Kaina, B. DNA Damage-Induced Cell Death: From Specific DNA Lesions to the DNA Damage Response and Apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2013, 332, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimmer, E.E.; Essigmann, J.M. Cisplatin. Essays Biochem. 1999, 34, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiola, E.; Salles, D.; Frapolli, R.; Lupi, M.; Rotella, G.; Ronchi, A.; Garassino, M.C.; Mattschas, N.; Colavecchio, S.; Broggini, M.; et al. Base Excision Repair-Mediated Resistance to Cisplatin in KRAS(G12C) Mutant NSCLC Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 30072–30087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Takehiro, K.; Zhan, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, H. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies in Overcoming Chemotherapy Resistance in Cancer. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.M.; Rocha, C.R.R.; Kinker, G.S.; Pelegrini, A.L.; Menck, C.F.M. The Balance between NRF2/GSH Antioxidant Mediated Pathway and DNA Repair Modulates Cisplatin Resistance in Lung Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Gutiérrez, R.E.; Alfaro-Mora, Y.; Andonegui, M.A.; Díaz-Chávez, J.; Herrera, L.A. The Influence of Oncogenic RAS on Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy Resistance Through DNA Repair Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 751367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Wang, Y.A. Conquering Oncogenic KRAS and Its Bypass Mechanisms. Theranostics 2022, 12, 5691–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Pereira, F.; Reis, C.; Oliveira, M.J.; Sousa, M.J.; Preto, A. Crucial Role of Oncogenic KRAS Mutations in Apoptosis and Autophagy Regulation: Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2022, 11, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Fan, Y. Combined KRAS and TP53 Mutation in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Enhance Chemoresistance to Promote Postoperative Recurrence and Metastasis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hientz, K.; Mohr, A.; Bhakta-Guha, D.; Efferth, T. The Role of P53 in Cancer Drug Resistance and Targeted Chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 8921–8946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, P.; Tang, J.; Yang, S.; Nicot, C.; Guan, Z.; Li, X.; Tang, H. Clinical Approaches to Overcome PARP Inhibitor Resistance. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.-T.; Burkett, S.S.; Tandon, M.; Yamamoto, T.M.; Gupta, N.; Bitler, B.G.; Lee, J.-M.; Nair, J.R. Distinct Roles of Treatment Schemes and BRCA2 on the Restoration of Homologous Recombination DNA Repair and PARP Inhibitor Resistance in Ovarian Cancer. Oncogene 2022, 41, 5020–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Shim, J.S. Targeting Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) to Overcome Drug Resistance in Cancer. Molecules 2016, 21, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Steed, A.; Co, M.; Chen, X. Cancer Stem Cells, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, ATP and Their Roles in Drug Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 684–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, H.; Toyota, M.; Aoki, F.; Akashi, H.; Maruyama, R.; Sasaki, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Idogawa, M.; Kashima, L.; Yanagihara, K.; et al. A Novel Method, Digital Genome Scanning Detects KRAS Gene Amplification in Gastric Cancers: Involvement of Overexpressed Wild-Type KRAS in Downstream Signaling and Cancer Cell Growth. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahcall, M.; Awad, M.M.; Sholl, L.M.; Wilson, F.H.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Palakurthi, S.; Choi, J.; Ivanova, E.V.; Leonardi, G.C.; et al. Amplification of Wild Type KRAS Imparts Resistance to Crizotinib in MET Exon 14 Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 5963–5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Jiang, L.; Maldonato, B.J.; Wang, Y.; Holderfield, M.; Aronchik, I.; Winters, I.P.; Salman, Z.; Blaj, C.; Menard, M.; et al. Translational and Therapeutic Evaluation of RAS-GTP Inhibition by RMC-6236 in RAS-Driven Cancers. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 994–1017, Erratum in Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Guan, X.; Zhang, X.; Luan, X.; Song, Z.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, W.; Qin, J.-J. Targeting KRAS Mutant Cancers: From Druggable Therapy to Drug Resistance. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, E.S.; Keane, F.K.; Lindner, R.; Tassi, R.A.; Paranjape, T.; Glasgow, M.; Nallur, S.; Deng, Y.; Lu, L.; Steele, L.; et al. A KRAS Variant Is a Biomarker of Poor Outcome, Platinum Chemotherapy Resistance and a Potential Target for Therapy in Ovarian Cancer. Oncogene 2012, 31, 4559–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clamp, A.R.; James, E.C.; McNeish, I.A.; Dean, A.; Kim, J.-W.; O’Donnell, D.M.; Gallardo-Rincon, D.; Blagden, S.; Brenton, J.; Perren, T.J.; et al. Weekly Dose-Dense Chemotherapy in First-Line Epithelial Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer Treatment (ICON8): Overall Survival Results from an Open-Label, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akin, J.M.; Waddell, J.A.; Solimando, D.A. Paclitaxel and Carboplatin (TC) Regimen for Ovarian Cancer. Hosp. Pharm. 2014, 49, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.G. First-Line Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer: Inferences from Recent Studies. The Oncologist 2016, 21, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carboplatin/Paclitaxel Induction in Ovarian Cancer: The Finer Points | CancerNetwork. Available online: https://www.cancernetwork.com/view/carboplatinpaclitaxel-induction-ovarian-cancer-finer-points (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Watters, K.M.; Bajwa, P.; Kenny, H.A. Organotypic 3D Models of the Ovarian Cancer Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2018, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma Chaundler, C.S.; Lu, H.; Fu, R.; Wang, N.; Lou, H.; De Almeida, G.S.; Hadi, L.M.; Aboagye, E.O.; Ghaem-Maghami, S. Kinetics and Efficacy of Antibody Drug Conjugates in 3D Tumour Models. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniati, E.; Berlato, C.; Gopinathan, G.; Heath, O.; Kotantaki, P.; Lakhani, A.; McDermott, J.; Pegrum, C.; Delaine-Smith, R.M.; Pearce, O.M.T.; et al. Mouse Ovarian Cancer Models Recapitulate the Human Tumor Microenvironment and Patient Response to Treatment. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 525–540.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.M.; Ho, G.Y.; Chu, S. Patient-Derived Xenograft Models for Ovarian Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2806, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradács, I.; Teutsch, B.; Váradi, A.; Bilá, A.; Vincze, Á.; Hegyi, P.; Fazekas, T.; Komoróczy, B.; Nyirády, P.; Ács, N.; et al. PARP Inhibitor Era in Ovarian Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitskell, K.; Rogozińska, E.; Platt, S.; Chen, Y.; Abd El Aziz, M.; Tattersall, A.; Morrison, J. Angiogenesis Inhibitors for the Treatment of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 4, CD007930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, S.; Devanaboyina, M.; Staats, H.; Stanbery, L.; Nemunaitis, J. Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy and Personalized Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; He, L.; Aittokallio, T.; Tang, J. SynergyFinder: A Web Application for Analyzing Drug Combination Dose–Response Matrix Data. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2413–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|

| PR | GGT GGA AGG GGC AGA AGA GAA AAG TTT TGA AAA GAG AAG ACG GGG AAG GTG G |

| PPRH2 | GGG GAG AAG GAG GGG GCC GGG TTT TGG GCC GGG GGA GGA AGA GGG G |

| Sc9 | AAG AAG AAG AAG AGA AGA ATT TTA AGA AGA GAA GAA GAA GAA |

| KRAS sgRNA F | CAC CGC CGC TCC TCC CCC GCC GGC C |

| KRAS sgRNA R | AAA CGG CCG GCG GGG GAG GAG CGG C |

| KRAS F | GAT GCG TTC CGC GCT CGA |

| KRAS R | AGT CCC TCC TCC CGC CAA |

| F13 F | GAG GTT GCA CTC CAG CCT TT |

| F13 R | ATG CCA TGC AGA TTA GAA A |

| KRAS siRNA F | TCG AGC TTG TGG TAG TTC CTG CTG GTG |

| KRAS siRNA R | GTA CCA CCA GCA GGA ACT ACC ACA AGC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Psaras, A.M.; McKay, S.J.; Vasquez Vilela, J.; Ospina Sanchez, E.; Cintrón, M.G.; Elder, K.K.; Brooks, T.A. Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility and Chemosensitivity to KRAS Modulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031571

Psaras AM, McKay SJ, Vasquez Vilela J, Ospina Sanchez E, Cintrón MG, Elder KK, Brooks TA. Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility and Chemosensitivity to KRAS Modulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031571

Chicago/Turabian StylePsaras, Alexandra Maria, Steven J. McKay, Janelle Vasquez Vilela, Eddison Ospina Sanchez, Marina G. Cintrón, Kayla K. Elder, and Tracy A. Brooks. 2026. "Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility and Chemosensitivity to KRAS Modulation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031571

APA StylePsaras, A. M., McKay, S. J., Vasquez Vilela, J., Ospina Sanchez, E., Cintrón, M. G., Elder, K. K., & Brooks, T. A. (2026). Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility and Chemosensitivity to KRAS Modulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031571