Hybrid Fe3O4-Gd2O3 Nanoparticles Prepared by High-Energy Ball Milling for Dual-Contrast Agent Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, A.J.; Kaza, E.; Singer, L.; Rosenberg, S.A. A review of the role of MRI in diagnosis and treatment of early stage lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 24, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.C. A new understanding on the development of MRI for cancer detection. Discov. Phys. 2025, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshomrani, F. Recent Advances in Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the Diagnosis of Liver Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Andaloussi, M.A.; Hormuth, D.A.; Lima, E.A.B.F.; Lorenzo, G.; Stowers, C.E.; Ravula, S.; Levac, B.; Dimakis, A.G.; Tamir, J.I.; et al. A critical assessment of artificial intelligence in magnetic resonance imaging of cancer. NPJ Imaging 2025, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinharay, S.; Pagel, M.D. Advances in Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents for Biomarker Detection. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2016, 9, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumfield, E.; Swenson, D.W.; Iyer, R.S.; Stanescu, A.L. Gadolinium-based contrast agents—Review of recent literature on magnetic resonance imaging signal intensity changes and tissue deposits, with emphasis on pediatric patients. Pediatr. Radiol. 2019, 49, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiarelli, L.; Bernetti, C.; Pugliese, L.; Greco, F.; Beomonte Zobel, B.; Mallio, C.A. Manganese-Based Contrast Agents as Alternatives to Gadolinium: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopalrao, S.N.; Rudresh, J.; Nagaraja, K.K. Panoptic overview of morphotropic phase boundary in improving ferroelectric properties of Gd doped bismuth ferrite. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2026, 208, 113228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboushoushah, S.F.O. Iron oxide nanoparticles enhancing magnetic resonance imaging: A review of the latest advancements. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2025, 10, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheev, V.A.; Nizamov, T.R.; Nikolenko, P.I.; Ivanova, A.V.; Novikov, A.I.; Dorofievich, I.V.; Lileev, A.S.; Abakumov, M.A.; Shchetinin, I.V. The Influence of Milling Conditions on the Structure and Properties of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Crystals 2024, 14, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamov, T.; Yanchen, L.; Bordyuzhin, I.; Mikheev, V.; Abakumov, M.; Shchetinin, I.; Savchenko, A. Seed-Mediated Continuous Growth of CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles in Triethylene Glycol Media: Role of Temperature and Injection Speed. J. Clust. Sci. 2025, 36, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, S.; Dini, G.; Zahraei, M. Polyethylene glycol-coated manganese-ferrite nanoparticles as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 475, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitin, D.; Bullinger, F.; Dobrynin, S.; Engelmann, J.; Scheffler, K.; Kolokolov, M.; Krumkacheva, O.; Buckenmaier, K.; Kirilyuk, I.; Chubarov, A. Contrast Agents Based on Human Serum Albumin and Nitroxides for 1H-MRI and Overhauser-Enhanced MRI. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu-Quang, H.; Vinding, M.S.; Nielsen, T.; Ullisch, M.G.; Nielsen, N.C.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Kjems, J. Pluronic F127-Folate Coated Super Paramagenic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as Contrast Agent for Cancer Diagnosis in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Polymers 2019, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.; Ramadan, E.; Elsadek, N.E.; Emam, S.E.; Shimizu, T.; Ando, H.; Ishima, Y.; Elgarhy, O.H.; Sarhan, H.A.; Hussein, A.K.; et al. Polyethylene glycol (PEG): The nature, immunogenicity, and role in the hypersensitivity of PEGylated products. J. Control. Release 2022, 351, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, S.; Rocha, S.; Sousa, N.R.; Catarino, C.; Belo, L.; Bronze-da-Rocha, E.; Valente, M.J.; Santos-Silva, A. Toxicity Mechanisms of Gadolinium and Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarciglia, A.; Papi, C.; Romiti, C.; Leone, A.; Di Gregorio, E.; Ferrauto Fir, G. Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents (GBCAs) for MRI: A Benefit–Risk Balance Analysis from a Chemical, Biomedical, and Environmental Point of View. Glob. Chall. 2025, 9, 2400269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulugeta, E.; Tegafaw, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, X.; Baek, A.; Kim, J.; Chang, Y.; Lee, G.H. Current Status and Future Aspects of Gadolinium Oxide Nanoparticles as Positive Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamov, T.R.; Iliasov, A.R.; Vodopyanov, S.S.; Kozhina, I.V.; Bordyuzhin, I.G.; Zhukov, D.G.; Ivanova, A.V.; Permyakova, E.S.; Mogilnikov, P.S.; Vishnevskiy, D.A.; et al. Study of Cytotoxicity and Internalization of Redox-Responsive Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on PC-3 and 4T1 Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurczewska, J.; Dobosz, B. Recent Progress and Challenges Regarding Magnetite-Based Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, Z.R.; Kievit, F.M.; Zhang, M. Magnetite Nanoparticles for Medical MR Imaging. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Albadawi, H.; Chong, B.W.; Deipolyi, A.R.; Sheth, R.A.; Khademhosseini, A.; Oklu, R. Advances in Biomaterials and Technologies for Vascular Embolization. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazi, R.; Ibrahim, T.K.; Nasir, J.A.; Gai, S.; Ali, G.; Boukhris, I.; Rehman, Z. Iron oxide based magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia, MRI and drug delivery applications: A review. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 11587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkashvand, N.; Sarlak, N. Fabrication of a dual T1 and T2 contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging using cellulose nanocrystals/Fe3O4 nanocomposite. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelkina, O.N.; Lodge, R.W.; Rudakovskaya, P.G.; Gerasimov, V.M.; Lucas, C.H.; Grebennikov, I.S.; Shchetinin, I.V.; Savchenko, A.G.; Pavlovskaya, G.E.; Rance, G.A.; et al. Nanoscale engineering of hybrid magnetite–carbon nanofibre materials for magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 2167–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, E.S.; Bordyuzhin, I.G.; Nizamov, T.R.; Nikitin, A.A.; Abakumov, M.A.; Dorofievich, I.V.; Baranova, Y.A.; Kovalev, A.D.; Nikolenko, P.I.; Chernyshev, B.D.; et al. Synthesis, structure and properties of nanoparticles based on SrFe12-xRxO19 (R = Er, Tm) compounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 585, 171127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanzadeh-Kouyakhi, A.; Masoudi, A.; Ardestani, M. Synthesis method of novel Gd2O3@Fe3O4 nanocomposite modified by dextrose capping agent. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 13442–13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, L.T.T.; Linh, N.T.N.; Tam, L.T.; Thiet, D.V.; Nam, P.H.; Hoa, N.T.H.; Tuan, L.A.; Dung, N.T.; Lu, L.T. Biocompatible PMAO-coated Gd2O3/Fe3O4 composite nanoparticles as an effective T1–T2 dual-mode contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhi, D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Nan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Qiu, B.; Wen, L.; Liang, G. Core/shell Fe3O4/Gd2O3 nanocubes as T1–T2 dual modal MRI contrast agents. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikhani, A.; Alamzadeh, Z.; Beik, J.; Irajirad, R.; Mirrahimi, M.; Mahabadi, V.P.; Kamrava, S.K.; Ghaznavi, H.; Khoei, S. Ultrasmall Fe3O4 and Gd2O3 hybrid nanoparticles for T1-weighted MR imaging of cancer. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2022, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Duan, J.; Yu, D.; Sang, Y. Ultrasmall Fe3O4 nanoparticles self-assembly induced dual-mode T1/T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and enhanced tumor synergetic theranostics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ni, S.; Chen, Z. Synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles by wet milling iron powder in a planetary ball mill. China Particuol. 2007, 5, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, M.M.; Ozcan, S.; Ceylan, A.; Firat, T. Effect of milling time on the synthesis of magnetite nanoparticles by wet milling. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2010, 172, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yi, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Kang, Z. Synthesis of CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles by a Low Temperature Microwave-Assisted Ball-Milling Technique. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2014, 11, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchetinin, I.V.; Seleznev, S.V.; Dorofievich, I.V. Structure and Magnetic Properties of Nanoparticles of Magnetite Obtained by Mechanochemical Synthesis. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2021, 63, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Liao, H.; Hou, Y.; Gao, S. Octahedral Fe3O4 nanoparticles and their assembled structures. Chem. Commun. 2009, 29, 4378–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdt, J.I.; Goya, G.F.; Calatayud, M.P.; Hereñú, C.B.; Reggiani, P.C.; Goya, R.G. Magnetic Field-Assisted Gene Delivery: Achievements and Therapeutic Potential. Curr. Gene Ther. 2012, 12, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crangle, J.; Goodman, G.M.; Sucksmith, W. The magnetization of pure iron and nickel. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1971, 321, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, G.; Srivastava, R.C.; Reddy, V.R.; Agrawal, H.M. Effect of sintering temperature on magnetization and Mössbauer parameters of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 427, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasz, K.; Ijiri, Y.; Krycka, K.L.; Borchers, J.A.; Booth, R.A.; Oberdick, S.; Majetich, S.A. Particle moment canting in CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 180405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanikaivelan, E.; Raj, S.G.; Murugakoothan, P. Synthesis and characterisation of erbium doped gadolinium oxide (Er:Gd2O3) nanorods. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press, corrected proof. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopathi, G.; Raj, S.G.; Kumar, G.R.; Mohan, R. Co-precipitation Synthesis, Structural and Luminescent Behavior of Erbium Doped Gadolinium Oxide (Er3+:Gd2O3) Nano-rods. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 1436–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.B.; Muñoz, A.; Anzellini, S.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; Turnbull, R.; Díaz-Anichtchenko, D.; Popescu, C.; Errandonea, D. Role of GdO addition in the structural stability of cubic Gd2O3 at high pressures: Determination of the equation of states of GdO and Gd2O3. Materialia 2024, 34, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Xiao, W.; Li, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D. Pressure-induced phase transformations in cubic Gd2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 073507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Bodnar, W.; Mix, T.; Schell, N.; Fulda, G.; Woodcock, T.G.; Burkel, E. A detailed study on the transition from the blocked to the superparamagnetic state of reduction-precipitated iron oxide nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 403, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, V.; Lahiri, B.B.; Louis, C.; Philip, J.; Damodaran, S.P. Size-controlled synthesis of superparamagnetic magnetite nanoclusters for heat generation in an alternating magnetic field. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 281, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadadian, Y.; Masoomi, H.; Dinari, A.; Ryu, C.; Hwang, S.; Kim, S.; Cho, B.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Yoon, J. From Low to High Saturation Magnetization in Magnetite Nanoparticles: The Crucial Role of the Molar Ratios Between the Chemicals. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 15996–16012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamov, T.R.; Bordyuzhin, I.G.; Mogilnikov, P.S.; Permyakova, E.S.; Abakumov, M.A.; Shchetinin, I.V.; Savchenko, A.G. Effect of synthetic conditions on the structure and magnetic properties of iron oxide nanoparticles in diethylene glycol medium. J. Nanopart. Res. 2024, 26, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, A.G.; Niznansky, D.; Poltierova-Vejpravova, J.; Bittova, B.; González-Fernández, M.A.; Serna, C.J.; Morales, M.P. Magnetite nanoparticles with no surface spin canting. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 114309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Diaz-Diestra, D.; Beltran-Huarac, J.; Weiner, B.R.; Morell, G. Enhanced MRI T2 Relaxivity in Contrast-Probed Anchor-Free PEGylated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleznev, S.V.; Bordyuzhin, I.G.; Nizamov, T.R.; Mikheev, V.A.; Abakumov, M.A.; Shchetinin, I.V. Structure, magnetic properties and hyperthermia of Fe3-xCoxO4 nanoparticles obtained by wet high-energy ball milling. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 167, 112679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdick, S.D.; Jordanova, K.V.; Lundstrom, J.T.; Parigi, G.; Poorman, M.E.; Zabow, G.; Keenan, K.E. Iron oxide nanoparticles as positive T1 contrast agents for low-field magnetic resonance imaging at 64 mT. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Nizamov, T.R.; Abakumov, M.A.; Shchetinin, I.V.; Savchenko, A.G.; Majouga, A.G. Effect of Magnetite Nanoparticle Morphology on the Parameters of MRI Relaxivity. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2018, 82, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchetinin, I.V.; Nikolenko, P.I.; Nizamov, T.R.; Novikov, A.I.; Ivanova, A.V.; Zanaeva, E.N.; Kartsev, A.I.; Davydov, N.D.; Abakumov, M.A.; Lileev, A.S. Effect of doping on structure and functional properties of SrFe12-xInxO19 hexaferrite nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Phase Content, % | Phase Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 () | c-Gd2O3 () | m-Gd2O3 () | aFe3O4, nm (0.0002) | DFe3O4, nm | ac-Gd2O3, nm (0.0002) | Dc-Gd2O3, nm | Dm-Gd2O3, nm | |

| Fe3O4 | 100 | - | - | 0.8396 | 23.7 ± 0.5 | - | - | - |

| Gd2O3 | - | 100 | - | - | - | 1.0815 | 29.7 ± 1.2 | - |

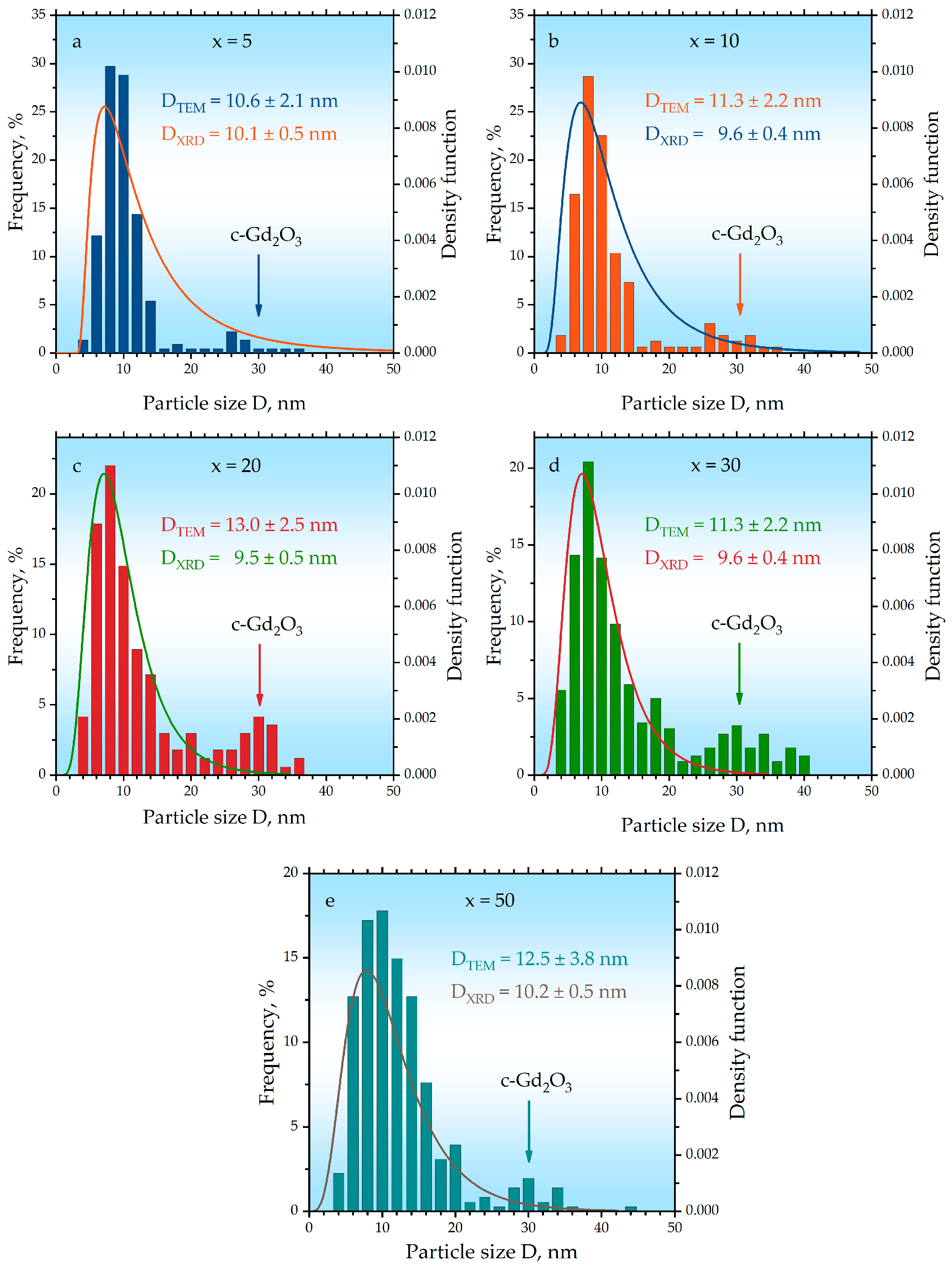

| x = 5 | 96 ± 3 | 4 ± 1 | - | 0.8370 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 1.0809 | 25.8 ± 1.2 | - |

| x = 10 | 92 ± 3 | 8 ± 2 | - | 0.8372 | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0811 | 25.1 ± 1.2 | - |

| x = 20 | 84 ± 3 | 9 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 0.8370 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0811 | 25.7 ± 1.2 | 9.1 ± 0.5 |

| x = 30 | 73 ± 3 | 12 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | 0.8368 | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0807 | 26.7 ± 1.2 | 8.7 ± 0.5 |

| x = 50 | 53 ± 3 | 15 ± 2 | 32 ± 3 | 0.8372 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0813 | 27.1 ± 1.2 | 8.3 ± 0.5 |

| Sample | Coercivity Hc, kA/m | Specific Remanent Magnetization σr, A·m2/kg | Specific Saturation Magnetization σs, A·m2/kg | r1, mmol/L/s | r2, mmol/L/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | 12 ± 1 | 11.9 ± 0.1 | 75.8 ± 0.5 | - | - |

| x = 5 | 9 ± 1 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 42.3 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 5 |

| x = 10 | 9 ± 1 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 41.8 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 111 ± 5 |

| x = 20 | 8 ± 1 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 38.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 161 ± 17 |

| x = 30 | 7 ± 1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 31.7 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ±0.1 | 131 ± 8 |

| x = 50 | 9 ± 1 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 25.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 164 ± 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mikheev, V.A.; Nizamov, T.R.; Novikov, A.I.; Abakumov, M.A.; Lileev, A.S.; Shchetinin, I.V. Hybrid Fe3O4-Gd2O3 Nanoparticles Prepared by High-Energy Ball Milling for Dual-Contrast Agent Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020910

Mikheev VA, Nizamov TR, Novikov AI, Abakumov MA, Lileev AS, Shchetinin IV. Hybrid Fe3O4-Gd2O3 Nanoparticles Prepared by High-Energy Ball Milling for Dual-Contrast Agent Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020910

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikheev, Vladislav A., Timur R. Nizamov, Alexander I. Novikov, Maxim A. Abakumov, Alexey S. Lileev, and Igor V. Shchetinin. 2026. "Hybrid Fe3O4-Gd2O3 Nanoparticles Prepared by High-Energy Ball Milling for Dual-Contrast Agent Applications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020910

APA StyleMikheev, V. A., Nizamov, T. R., Novikov, A. I., Abakumov, M. A., Lileev, A. S., & Shchetinin, I. V. (2026). Hybrid Fe3O4-Gd2O3 Nanoparticles Prepared by High-Energy Ball Milling for Dual-Contrast Agent Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020910