Acute Dehydration Drives Organ-Specific Modulation of Phosphorylated AQP4ex in Brain and Kidney

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

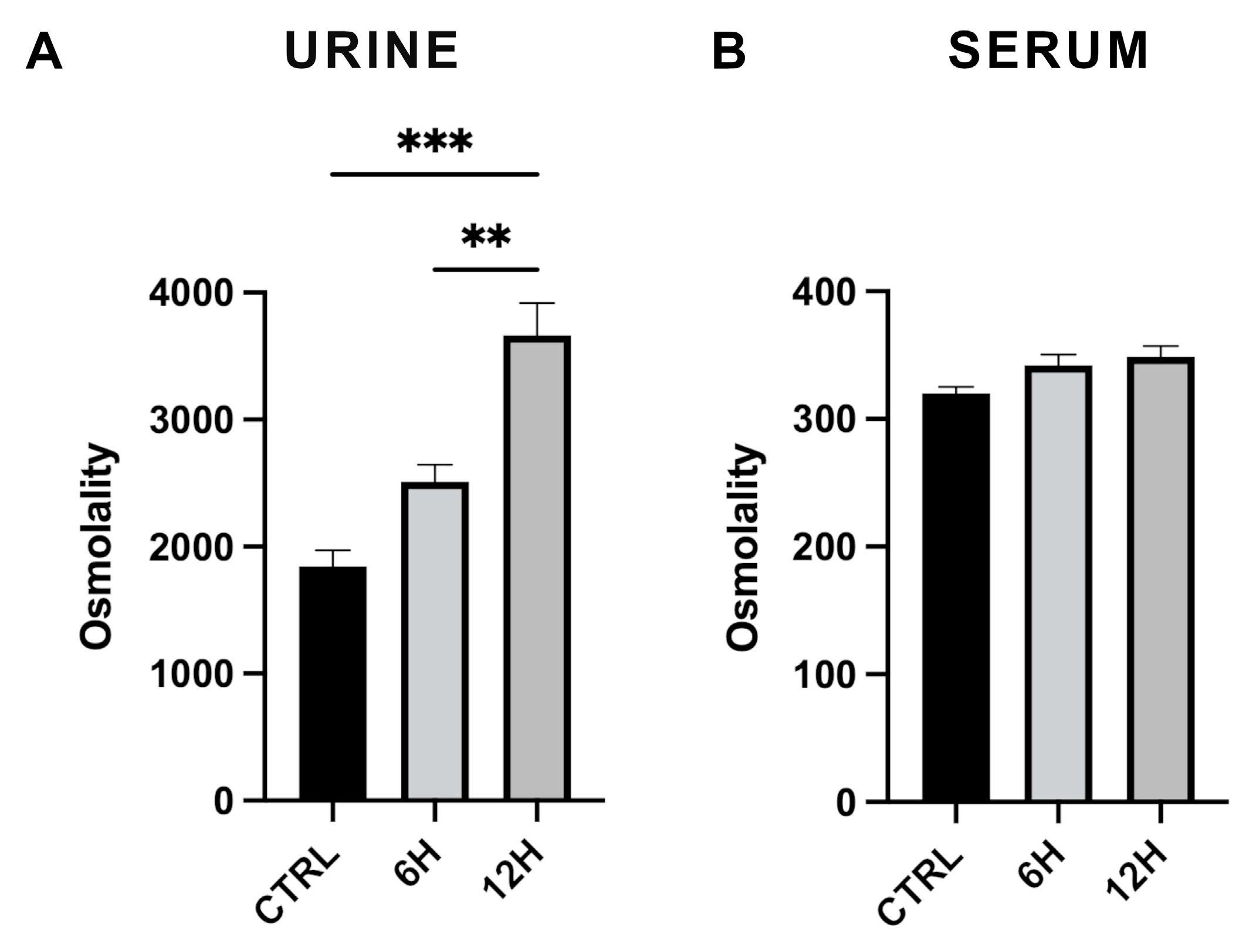

2.1. Effect of Acute Water Deprivation on Urine and Plasma Osmolality

2.2. AQP4 Isoforms Expression and Localization in Mouse Kidney After Water Deprivation

2.3. AQP4 Isoforms Expression and Localization in Mouse CNS After Water Deprivation

3. Discussion

3.1. Renal Response: Phosphorylation of AQP4ex Supports Water Reabsorption

3.2. Cerebral Response: Reduced pAQP4ex as a Protective Mechanism

3.3. Role of AQP4ex Phosphorylation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Urine and Serum Chemistry

4.3. Antibodies

4.4. Immunofluorescence on Tissue Sections

4.5. Quantitative Immunofluorescence Analysis

4.6. Plasma Membrane Vesicles from Kidney Medulla

4.7. Sample Preparation for SDS-PAGE

4.8. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verkman, A.S.; Anderson, M.O.; Papadopoulos, M.C. Aquaporins: Important but Elusive Drug Targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knepper, M.A. The Aquaporin Family of Molecular Water Channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 6255–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S.; Mitra, A.K. Structure and Function of Aquaporin Water Channels. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2000, 278, F13–F28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acierno, M.; Fenton, R.A.; Hoorn, E.J. The Biology of Water Homeostasis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, T.; Rodriguez-Grande, B.; Badaut, J. Aquaporins in Brain Edema. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigeri, A.; Gropper, M.A.; Umenishi, F.; Kawashima, M.; Brown, D.; Verkman, A.S. Localization of MIWC and GLIP Water Channel Homologs in Neuromuscular, Epithelial and Glandular Tissues. J. Cell Sci. 1995, 108, 2993–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.D.; Yeh, R.; Sandstrom, A.; Chorny, I.; Harries, W.E.C.; Robbins, R.A.; Miercke, L.J.W.; Stroud, R.M. Crystal Structure of Human Aquaporin 4 at 1.8 Å and Its Mechanism of Conductance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7437–7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Ratelade, J.; Papadopoulos, M.C.; Bennett, J.L.; Verkman, A.S. Neuromyelitis Optica IgG Does Not Alter Aquaporin-4 Water Permeability, Plasma Membrane M1/M23 Isoform Content, or Supramolecular Assembly. Glia 2012, 60, 2027–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, C.S.; Gorelick-Feldman, D.A.; Davidson, K.G.V.; Yasumura, T.; Neely, J.D.; Agre, P.; Rash, J.E. Aquaporin-4 Square Array Assembly: Opposing Actions of M1 and M23 Isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13609–13614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.-J.; Rossi, A.; Verkman, A.S. Model of Aquaporin-4 Supramolecular Assembly in Orthogonal Arrays Based on Heterotetrameric Association of M1-M23 Isoforms. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2936–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bellis, M.; Pisani, F.; Mola, M.G.; Rosito, S.; Simone, L.; Buccoliero, C.; Trojano, M.; Nicchia, G.P.; Svelto, M.; Frigeri, A. Translational Readthrough Generates New Astrocyte AQP4 Isoforms That Modulate Supramolecular Clustering, Glial Endfeet Localization, and Water Transport. Glia 2017, 65, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, R.; Palazzo, C.; Valente, O.; Abbrescia, P.; Messina, R.; Surdo, N.C.; Lefkimmiatis, K.; Signorelli, F.; Nicchia, G.P.; Frigeri, A. The Readthrough Isoform AQP4ex Is Constitutively Phosphorylated in the Perivascular Astrocyte Endfeet of Human Brain. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, C.; Buccoliero, C.; Mola, M.G.; Abbrescia, P.; Nicchia, G.P.; Trojano, M.; Frigeri, A. AQP4ex Is Crucial for the Anchoring of AQP4 at the Astrocyte End-Feet and for Neuromyelitis Optica Antibody Binding. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, C.; Abbrescia, P.; Valente, O.; Nicchia, G.P.; Banitalebi, S.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Trojano, M.; Frigeri, A. Tissue Distribution of the Readthrough Isoform of AQP4 Reveals a Dual Role of AQP4ex Limited to CNS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Wang, M.X.; Ismail, O.; Braun, M.; Schindler, A.G.; Reemmer, J.; Wang, Z.; Haveliwala, M.A.; O’Boyle, R.P.; Han, W.Y.; et al. Loss of Perivascular Aquaporin-4 Localization Impairs Glymphatic Exchange and Promotes Amyloid β Plaque Formation in Mice. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.M.; Kitchen, P.; Halsey, A.; Wang, M.X.; Törnroth-Horsefield, S.; Conner, A.C.; Badaut, J.; Iliff, J.J.; Bill, R.M. Emerging Roles for Dynamic Aquaporin-4 Subcellular Relocalization in CNS Water Homeostasis. Brain 2022, 145, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Yang, B.; Gillespie, A.; Carlson, E.J.; Epstein, C.J.; Verkman, A.S. Generation and Phenotype of a Transgenic Knockout Mouse Lacking the Mercurial-Insensitive Water Channel Aquaporin-4. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S.; Yang, B.; Song, Y.; Manley, G.T.; Ma, T. Role of Water Channels in Fluid Transport Studied by Phenotype Analysis of Aquaporin Knockout Mice. Exp. Physiol. 2000, 85, 233s–241s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.L.; Ma, T.; Yang, B.; Knepper, M.A.; Verkman, A.S. Fourfold Reduction of Water Permeability in Inner Medullary Collecting Duct of Aquaporin-4 Knockout Mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 1998, 274, C549–C554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N.; Ikegami, H.; Shimada, K. Effect of Water Deprivation on Aquaporin 4 (AQP4) mRNA Expression in Chickens (Gallus domesticus). Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 141, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedvetsky, P.I.; Tamma, G.; Beulshausen, S.; Valenti, G.; Rosenthal, W.; Klussmann, E. Regulation of Aquaporin-2 Trafficking. In Aquaporins; Beitz, E., Ed.; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 190, pp. 133–157. ISBN 978-3-540-79884-2. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo-Carretero, M.I.; Ilundáin, A.A.; Echevarria, M. Regulation of Aquaporin mRNA Expression in Rat Kidney by Water Intake. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999, 10, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtushenko, A.A.; Orlov, I.V.; Voronova, I.P.; Kozyreva, T.V. Functional Changes in the Expression of the Aqp4 Gene in the Hypothalamus Under the Influence of Drinking Regimen and Arterial Hypertension in Rats. Ross. Fiziol. žurnal Im. IM Sečenova 2024, 110, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes-Rodrigues, J.; De Castro, M.; Elias, L.L.K.; Valença, M.M.; McCANN, S.M. Neuroendocrine Control of Body Fluid Metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 169–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejsum, L.N.; Zelenina, M.; Aperia, A.; Frøkiær, J.; Nielsen, S. Bidirectional Regulation of AQP2 Trafficking and Recycling: Involvement of AQP2-S256 Phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2005, 288, F930–F938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, T.-H.; Frøkiær, J.; Nielsen, S. Regulation of Aquaporin-2 in the Kidney: A Molecular Mechanism of Body-Water Homeostasis. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 32, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khositseth, S.; Pisitkun, T.; Slentz, D.H.; Wang, G.; Hoffert, J.D.; Knepper, M.A.; Yu, M.-J. Quantitative Protein and mRNA Profiling Shows Selective Post-Transcriptional Control of Protein Expression by Vasopressin in Kidney Cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011, 10, M110.004036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Chou, C.L.; Marples, D.; Christensen, E.I.; Kishore, B.K.; Knepper, M.A. Vasopressin Increases Water Permeability of Kidney Collecting Duct by Inducing Translocation of Aquaporin-CD Water Channels to Plasma Membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenina, M.; Zelenin, S.; Bondar, A.A.; Brismar, H.; Aperia, A. Water Permeability of Aquaporin-4 Is Decreased by Protein Kinase C and Dopamine. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2002, 283, F309–F318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesverova, V.; Törnroth-Horsefield, S. Phosphorylation-Dependent Regulation of Mammalian Aquaporins. Cells 2019, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicchia, G.P.; Srinivas, M.; Li, W.; Brosnan, C.F.; Frigeri, A.; Spray, D.C. New Possible Roles for Aquaporin-4 in Astrocytes: Cell Cytoskeleton and Functional Relationship with Connexin43. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.M.; McFarland White, K.; Fass, S.B.; Chen, S.; Shi, Z.; Ge, X.; Engelbach, J.A.; Gaines, S.H.; Bice, A.R.; Vasek, M.J.; et al. Evaluation of Gliovascular Functions of AQP4 Readthrough Isoforms. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1272391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, A.S.; Rappold, P.M.; Fujita, T.; Torres, A.; Bekar, L.K.; Takano, T.; Peng, W.; Wang, F.; Rangroo Thrane, V.; Enger, R.; et al. Critical Role of Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in Astrocytic Ca2+ Signaling Events Elicited by Cerebral Edema. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellas, J.A.; Andrew, R.D. Neuronal Swelling: A Non-Osmotic Consequence of Spreading Depolarization. Neurocrit. Care 2021, 35, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraille, E.; Sassi, A.; Olivier, V.; Arnoux, G.; Martin, P.-Y. Renal Water Transport in Health and Disease. Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2022, 474, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danziger, J.; Zeidel, M.L. Osmotic Homeostasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 852–862, Correction in Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 1703. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.08340815.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, C.; Komaki, Y.; Deàs-Just, A.; Le Gac, B.; Mouffle, C.; Franco, C.; Chaperon, A.; Vialou, V.; Tsurugizawa, T.; Cauli, B.; et al. Astrocyte Aquaporin Mediates a Tonic Water Efflux Maintaining Brain Homeostasis. eLife 2024, 13, RP95873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, A.D.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Ottersen, O.P.; Adams, M.E.; Froehner, S.C. Assembly of a Perivascular Astrocyte Protein Scaffold at the Mammalian Blood–Brain Barrier Is Dependent on α-Syntrophin. Glia 2006, 53, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, E.S.; Haas, B.R.; Sontheimer, H. Water Permeability through Aquaporin-4 Is Regulated by Protein Kinase C and Becomes Rate-Limiting for Glioma Invasion. Neuroscience 2010, 168, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicchia, G.P.; Mastrototaro, M.; Rossi, A.; Pisani, F.; Tortorella, C.; Ruggieri, M.; Lia, A.; Trojano, M.; Frigeri, A.; Svelto, M. Aquaporin-4 Orthogonal Arrays of Particles Are the Target for Neuromyelitis Optica Autoantibodies. Glia 2009, 57, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, B.T.; Iliff, J.J.; Xia, M.; Wang, M.; Wei, H.S.; Zeppenfeld, D.; Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Liew, J.A.; et al. Impairment of Paravascular Clearance Pathways in the Aging Brain. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicchia, G.P.; Rossi, A.; Nudel, U.; Svelto, M.; Frigeri, A. Dystrophin-dependent and -independent AQP4 Pools Are Expressed in the Mouse Brain. Glia 2008, 56, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbrescia, P.; Signorile, G.; Valente, O.; Palazzo, C.; Cibelli, A.; Nicchia, G.P.; Frigeri, A. Crucial Role of Aquaporin-4 Extended Isoform in Brain Water Homeostasis and Amyloid-β Clearance: Implications for Edema and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Palazzo, C.; Pati, R.; Gatta, R.P.; Valente, O.; Abbrescia, P.; Nicchia, G.P.; Frigeri, A. Acute Dehydration Drives Organ-Specific Modulation of Phosphorylated AQP4ex in Brain and Kidney. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020617

Palazzo C, Pati R, Gatta RP, Valente O, Abbrescia P, Nicchia GP, Frigeri A. Acute Dehydration Drives Organ-Specific Modulation of Phosphorylated AQP4ex in Brain and Kidney. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020617

Chicago/Turabian StylePalazzo, Claudia, Roberta Pati, Raffaella Pia Gatta, Onofrio Valente, Pasqua Abbrescia, Grazia Paola Nicchia, and Antonio Frigeri. 2026. "Acute Dehydration Drives Organ-Specific Modulation of Phosphorylated AQP4ex in Brain and Kidney" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020617

APA StylePalazzo, C., Pati, R., Gatta, R. P., Valente, O., Abbrescia, P., Nicchia, G. P., & Frigeri, A. (2026). Acute Dehydration Drives Organ-Specific Modulation of Phosphorylated AQP4ex in Brain and Kidney. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020617