Modulation of the miR-485-3p/PGC-1α Pathway by ASO-Loaded Nanoparticles Attenuates ALS Pathogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Dysregulation of miR-485-3p in SOD1G93A-Expressing HMC3 Cells

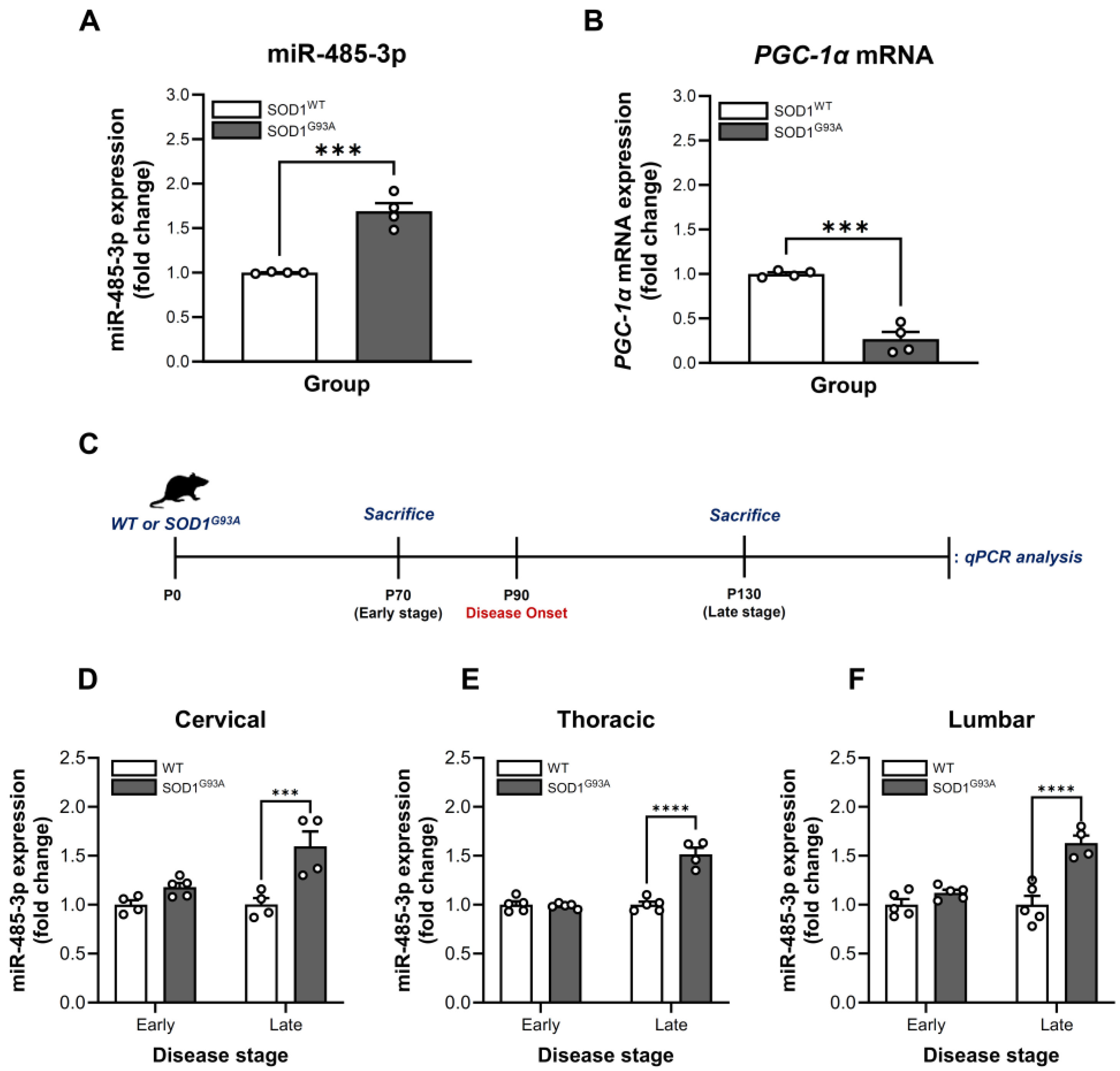

2.2. Stage- and Region-Specific Alterations of miR-485-3p Expression in SOD1G93A Transgenic Mice

2.3. Characterization of BMD-001S

2.4. Cytotoxicity and Pharmacological Effect of BMD-001S in SOD1G93A-Expressing HMC3 Cells

2.5. BMD-001S Enhanced PGC-1α Expression in the Spinal Cord Regions of SOD1G93A Transgenic Mice

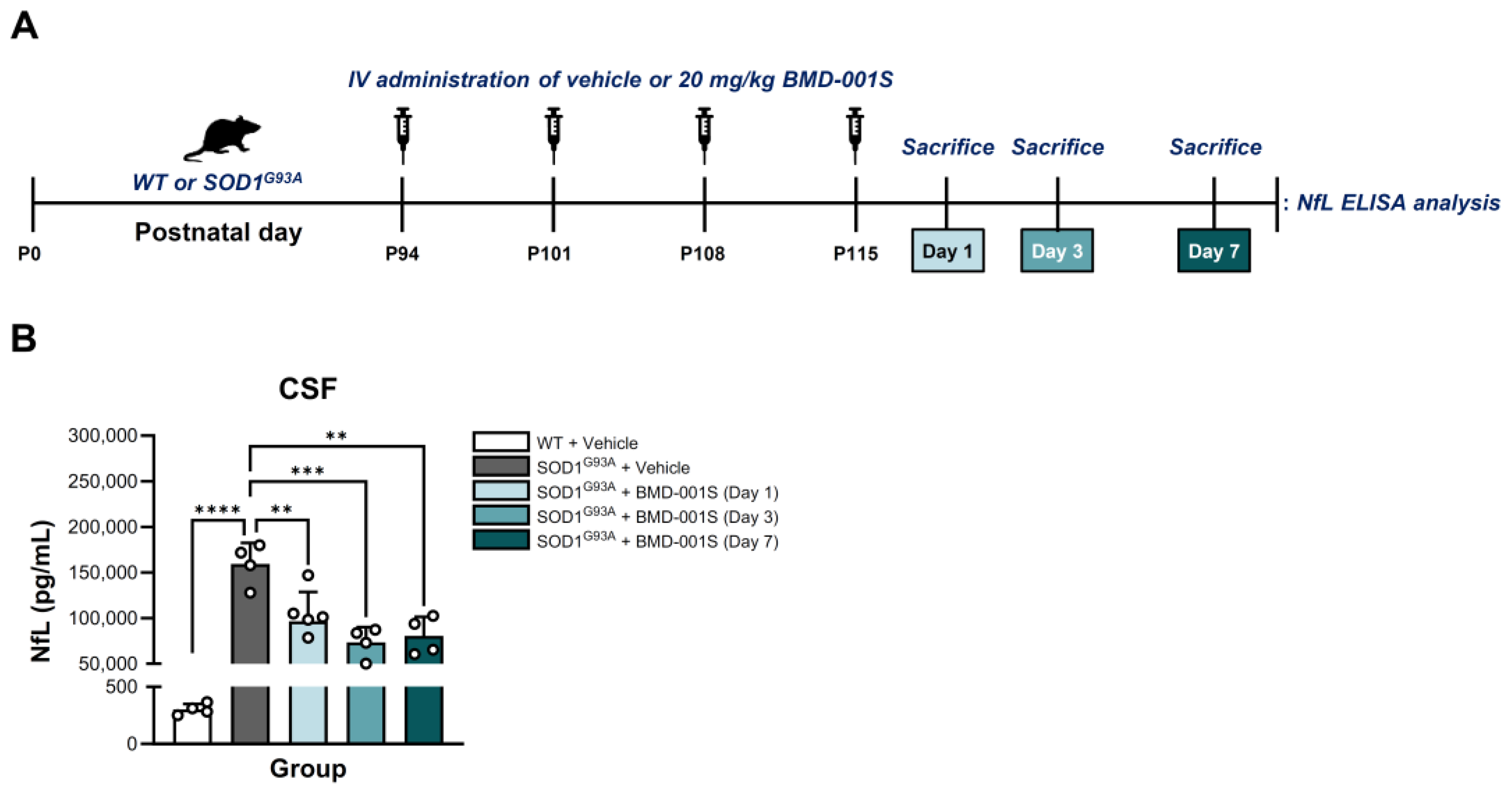

2.6. BMD-001S Reduced CSF Neurofilament Light Chain Levels in SOD1G93A Transgenic Mice

2.7. BMD-001S Improved Neuromuscular Function in SOD1G93A Transgenic Mice

2.8. BMD-001S Attenuates SOD1 Aggregation and Microglial Activation in the Lumbar Spinal Cord

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Generation of Stable SOD1WT or SOD1G93A-Expressing HMC3 Cell Lines

4.2. Animals

4.3. Experimental Design, Randomization, and Blinding

4.4. Target Gene Knockdown Analysis

4.4.1. RNA Extraction

4.4.2. qPCR Analysis

4.5. Preparation of BMD-001S

4.6. Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity Assays

4.7. Intravenous Administration of BMD-001S in SOD1G93A Transgenic Mice

4.8. Tissue and Sample Collection

4.8.1. Timeline for Tissue and Sample Collection

4.8.2. Spinal Cord Tissues Collection for qPCR and ELISA Analysis

4.8.3. CSF Collection

4.9. Gastrocnemius Muscle and Lumbar Spinal Cord Tissue Collection for Histological Analysis

4.10. ELISA

4.10.1. Quantification of PGC-1α Protein Levels in the Spinal Cord Tissues

4.10.2. Quantification of NfL Protein Levels in CSF

4.11. CMAP Measurement

4.12. Immunostaining

4.12.1. NMJ Staining

4.12.2. SOD1 Inclusion and Iba1 Immunostaining

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| BSCB | Blood-spinal cord barrier |

| CMAP | Compound motor action potential |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| EE | Encapsulation efficiency |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FACS | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| HMC3 | Human microglial clone 3 |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| Iba1 | Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LAT1 | L-type amino acid transporter 1 |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| NMJ | Neuromuscular junction |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDI | polydispersity index |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| qPCR | Quantitative PCR |

| RT | Room temperature |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| TBS | Tris-buffered saline |

| TBS-T | TBS with tween 20 |

| WT | Wild-type |

References

- Rowland, L.P.; Shneider, N.A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B.R.; Miller, R.G.; Swash, M.; Munsat, T.L. World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Disease. El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Mot. Neuron Disord. 2000, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Ferguson, T.A.; Cummings, C.; Hotchkin, M.T.; Genge, A.; Glanzman, R.; Roet, K.C.D.; Cudkowicz, M.; Kiernan, M.C. Gold Coast diagnostic criteria: Implications for ALS diagnosis and clinical trial enrollment. Muscle Nerve 2021, 64, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Chalabi, A.; Lewis, C.M. Modelling the effects of penetrance and family size on rates of sporadic and familial disease. Hum. Hered. 2011, 71, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, R.; Tada, M.; Shiga, A.; Toyoshima, Y.; Konno, T.; Sato, T.; Nozaki, H.; Kato, T.; Horie, M.; Shimizu, H.; et al. Heterogeneity of cerebral TDP-43 pathology in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Evidence for clinico-pathologic subtypes. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, L.J.; Raaphorst, J.; Aronica, E.; Baas, F.; de Haan, R.; de Visser, M.; Troost, D. Prevalence of brain and spinal cord inclusions, including dipeptide repeat proteins, in patients with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion: A systematic neuropathological review. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2016, 42, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.A.; Jackson, C.E.; Heiman-Patterson, T.D.; Bettica, P.; Brooks, B.R.; Pioro, E.P. Real-world evidence of riluzole effectiveness in treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2020, 21, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, M.K. Riluzole and edaravone: A tale of two amyotrophic lateral sclerosis drugs. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.; Cudkowicz, M.; Shaw, P.J.; Andersen, P.M.; Atassi, N.; Bucelli, R.C.; Genge, A.; Glass, J.; Ladha, S.; Ludolph, A.L.; et al. Phase 1-2 Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T.M.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Genge, A.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G.; Bucelli, R.C.; Chio, A.; Van Damme, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Glass, J.D.; et al. Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.G.; Mitchell, J.D.; Moore, D.H. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD001447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, R. Edaravone in ALS. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 217, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prodromidou, K.; Matsas, R. Species-Specific miRNAs in Human Brain Development and Disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.H.T.; Xu, B.; Blenkiron, C.; Fraser, M. Emerging Roles of miRNAs in Brain Development and Perinatal Brain Injury. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, J.; Jung, S.; Keller, S.; Gregory, R.I.; Diederichs, S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewski, J.; Lenart, J.; Salinska, E. MicroRNA in Brain pathology: Neurodegeneration the Other Side of the Brain Cancer. Noncoding RNA 2019, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilich, R.W.; Woodbury, M.E.; Ikezu, T. Integrated expression profiles of mRNA and miRNA in polarized primary murine microglia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.; Jin, L. Recent Advances in the Roles of MicroRNA and MicroRNA-Based Diagnosis in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheja, R.; Regev, K.; Healy, B.C.; Mazzola, M.A.; Beynon, V.; Von Glehn, F.; Paul, A.; Diaz-Cruz, C.; Gholipour, T.; Glanz, B.I.; et al. Correlating serum micrornas and clinical parameters in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2018, 58, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emde, A.; Eitan, C.; Liou, L.L.; Libby, R.T.; Rivkin, N.; Magen, I.; Reichenstein, I.; Oppenheim, H.; Eilam, R.; Silvestroni, A.; et al. Dysregulated miRNA biogenesis downstream of cellular stress and ALS-causing mutations: A new mechanism for ALS. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2633–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.J.; Min, J.W.; Iwatsubo, T.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cho, H.J.; Ryu, J.H. Targeting MicroRNA-485-3p Blocks Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13136, Correction in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, I.S.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, H.J.; Ryu, J.H. The role of microRNA-485 in neurodegenerative diseases. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 34, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, C.; Xiao, M.; Cheng, S.; Lu, X.; Jia, S.; Ren, Y.; Li, Z. MiR-485-3p and miR-485-5p suppress breast cancer cell metastasis by inhibiting PGC-1alpha expression. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschbach, J.; Schwalenstocker, B.; Soyal, S.M.; Bayer, H.; Wiesner, D.; Akimoto, C.; Nilsson, A.C.; Birve, A.; Meyer, T.; Dupuis, L.; et al. PGC-1alpha is a male-specific disease modifier of human and experimental amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 3477–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, N.; Knippenberg, S.; Korner, S.; Rath, K.J.; Dengler, R.; Petri, S. Decreased mRNA expression of PGC-1alpha and PGC-1alpha-regulated factors in the SOD1G93A ALS mouse model and in human sporadic ALS. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 71, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggs, W.J.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; Menkes, D.L. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 18-2006. A 57-year-old woman with numbness and weakness of the feet and legs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2584–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schujman, G.E.; Guerin, M.; Buschiazzo, A.; Schaeffer, F.; Llarrull, L.I.; Reh, G.; Vila, A.J.; Alzari, P.M.; de Mendoza, D. Structural basis of lipid biosynthesis regulation in Gram-positive bacteria. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4074–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludolph, A.C.; Bendotti, C.; Blaugrund, E.; Chio, A.; Greensmith, L.; Loeffler, J.P.; Mead, R.; Niessen, H.G.; Petri, S.; Pradat, P.F.; et al. Guidelines for preclinical animal research in ALS/MND: A consensus meeting. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarner, J.; Izazola, J.A.; del Rio Chiriboga, C. Problems in counting CD4+ T-cells. Rev. Investig. Clin. 1994, 46, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D.; Pardhan, S. Selective attention, ideal observer theory and ‘early’ visual channels. Spat. Vis. 2000, 14, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cen, Y.L.; Tang, L.Y.; Lin, Y.; Su, F.X.; Wu, B.H.; Ren, Z.F. Association between urinary cadmium and clinicopathological characteristics of breast cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2013, 35, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gurney, M.E.; Pu, H.; Chiu, A.Y.; Dal Canto, M.C.; Polchow, C.Y.; Alexander, D.D.; Caliendo, J.; Hentati, A.; Kwon, Y.W.; Deng, H.X.; et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science 1994, 264, 1772–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinsant, S.; Mansfield, C.; Jimenez-Moreno, R.; Del Gaizo Moore, V.; Yoshikawa, M.; Hampton, T.G.; Prevette, D.; Caress, J.; Oppenheim, R.W.; Milligan, C. Characterization of early pathogenesis in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of ALS: Part I, background and methods. Brain Behav. 2013, 3, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinsant, S.; Mansfield, C.; Jimenez-Moreno, R.; Del Gaizo Moore, V.; Yoshikawa, M.; Hampton, T.G.; Prevette, D.; Caress, J.; Oppenheim, R.W.; Milligan, C. Characterization of early pathogenesis in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of ALS: Part II, results and discussion. Brain Behav. 2013, 3, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, A.E.; Dominguez, S.L.; Yen, C.W.; Laufer, B.I.; Foreman, O.; Reichelt, M.; Lin, H.; Sagolla, M.; Hotzel, K.; Ngu, H.; et al. Lipid nanoparticle delivery limits antisense oligonucleotide activity and cellular distribution in the brain after intracerebroventricular injection. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuri, K.; Bechtold, C.; Quijano, E.; Pham, H.; Gupta, A.; Vikram, A.; Bahal, R. Antisense Oligonucleotides: An Emerging Area in Drug Discovery and Development. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ma, F.; Liu, F.; Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Q. Efficient Delivery of Antisense Oligonucleotides Using Bioreducible Lipid Nanoparticles In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 19, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.H.; Macdonald-Wallis, C.; Gray, E.; Pearce, N.; Petzold, A.; Norgren, N.; Giovannoni, G.; Fratta, P.; Sidle, K.; Fish, M.; et al. Neurofilament light chain: A prognostic biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2015, 84, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullard, A. NfL makes regulatory debut as neurodegenerative disease biomarker. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verde, F.; Otto, M.; Silani, V. Neurofilament Light Chain as Biomarker for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 679199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollari, E.; Prior, R.; Robberecht, W.; Van Damme, P.; Van Den Bosch, L. In Vivo Electrophysiological Measurement of Compound Muscle Action Potential from the Forelimbs in Mouse Models of Motor Neuron Degeneration. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 136, 57741. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, T.G.; Yoon, M.H.; Kang, S.M.; Park, S.; Cho, J.H.; Hwang, Y.J.; Ahn, J.; Jang, H.; Shin, Y.J.; Jung, E.M.; et al. Novel chemical inhibitor against SOD1 misfolding and aggregation protects neuron-loss and ameliorates disease symptoms in ALS mouse model. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nizzardo, M.; Simone, C.; Rizzo, F.; Ulzi, G.; Ramirez, A.; Rizzuti, M.; Bordoni, A.; Bucchia, M.; Gatti, S.; Bresolin, N.; et al. Morpholino-mediated SOD1 reduction ameliorates an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis disease phenotype. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, B.; D’Amico, A.G.; Maugeri, G.; Morello, G.; La Cognata, V.; Saccone, S.; Federico, C.; Cavallaro, S.; D’Agata, V. Neuroprotective effect of the PACAP-ADNP axis on SOD1G93A mutant motor neuron death induced by trophic factors deprivation. Neuropeptides 2023, 102, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Liu, Y.U.; Yao, X.; Qin, D.; Su, H. Variability in SOD1-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Geographic patterns, clinical heterogeneity, molecular alterations, and therapeutic implications. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neel, D.V.; Basu, H.; Gunner, G.; Chiu, I.M. Catching a killer: Mechanisms of programmed cell death and immune activation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 311, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, E.D.; Shaner, C.; Zhang, P.; du Maine, X.; Fischer, K.; Tay, J.; Chau, B.N.; Wu, G.F.; Miller, T.M. Method for widespread microRNA-155 inhibition prolongs survival in ALS-model mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 4127–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butovsky, O.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Cialic, R.; Krasemann, S.; Murugaiyan, G.; Fanek, Z.; Greco, D.J.; Wu, P.M.; Doykan, C.E.; Kiner, O.; et al. Targeting miR-155 restores abnormal microglia and attenuates disease in SOD1 mice. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 77, 75–99, Correction in Ann. Neurol. 2015, 77, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.H.; Valdez, G.; Moresi, V.; Qi, X.; McAnally, J.; Elliott, J.L.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Sanes, J.R.; Olson, E.N. MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science 2009, 326, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneteau, G.; Simonet, T.; Bauche, S.; Mandjee, N.; Malfatti, E.; Girard, E.; Tanguy, M.L.; Behin, A.; Khiami, F.; Sariali, E.; et al. Muscle histone deacetylase 4 upregulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Potential role in reinnervation ability and disease progression. Brain 2013, 136, 2359–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, I.S.; Kim, D.H.; Ro, J.Y.; Park, B.G.; Kim, S.H.; Im, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Yoon, S.J.; Kang, H.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The microRNA-485-3p concentration in salivary exosome-enriched extracellular vesicles is related to amyloid beta deposition in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Biochem. 2023, 118, 110603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolny, G.; Martone, J.; Lepore, E.; Casola, I.; Petrucci, A.; Inghilleri, M.; Morlando, M.; Colantoni, A.; Scicchitano, B.M.; Calvo, A.; et al. A longitudinal study defined circulating microRNAs as reliable biomarkers for disease prognosis and progression in ALS human patients. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.Y.; Kwon, M.S.; Oh, K.W.; Nahm, M.; Park, J.; Jin, H.K.; Bae, J.S.; Son, B.; Kim, S.H. miRNA-214 to predict progression and survival in ALS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 96, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awashra, M.; Mlynarz, P. The toxicity of nanoparticles and their interaction with cells: An in vitro metabolomic perspective. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 2674–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naahidi, S.; Jafari, M.; Edalat, F.; Raymond, K.; Khademhosseini, A.; Chen, P. Biocompatibility of engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery. J. Control Release 2013, 166, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, L.; Ju, Z.; Skonieczna, M.; Zhou, P.K.; Huang, R. Nanoparticles-induced potential toxicity on human health: Applications, toxicity mechanisms, and evaluation models. MedComm (2020) 2023, 4, e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.N.; Ryu, I.S.; Jung, Y.J.; Helmlinger, G.; Kim, I.; Park, H.W.; Kang, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, K.S.; et al. l-Type amino acid transporter 1-targeting nanoparticles for antisense oligonucleotide delivery to the CNS. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarski, C.A.; Hanley, P.J. Review of flow cytometry as a tool for cell and gene therapy. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, G.; Vandelli, M.A.; Forni, F.; Ruozi, B. Nanomedicine and neurodegenerative disorders: So close yet so far. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafede, R.; Mariotti, R. ALS Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Approaches: The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafe, M.R. Drug delivery for neurodegenerative diseases is a problem, but lipid nanocarriers could provide the answer. Nanotheranostics 2024, 8, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojdeh, S.; Safarkhani, M.; Daneshgar, H.; Aldhaher, A.; Heidari, G.; Nazarzadeh Zare, E.; Iravani, S.; Zarrabi, A.; Rabiee, N. Promising breakthroughs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis treatment through nanotechnology’s unexplored frontier. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 282, 117080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.R.; Yang, E.J. Oxidative Stress as a Therapeutic Target in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Opportunities and Limitations. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Huo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Meng, F.; Su, Q.; Bao, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. The Impact of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells 2022, 11, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Arosio, A.; Conti, E.; Beretta, S.; Lunetta, C.; Riva, N.; Ferrarese, C.; Tremolizzo, L. Riluzole Selective Antioxidant Effects in Cell Models Expressing Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Endophenotypes. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2019, 17, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, S.R.A.; Gomez, K.; Moutal, A.; Khanna, R. Putative roles of SLC7A5 (LAT1) transporter in pain. Neurobiol. Pain. 2020, 8, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akashi, T.; Noguchi, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Tomi, M. L-type Amino Acid Transporter 1 (SLC7A5)-Mediated Transport of Pregabalin at the Rat Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier and its Sensitivity to Plasma Branched-Chain Amino Acids. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 112, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, K.; Ushakov, K.; Pozniak, Y.; Yizhar-Barnea, O.; Bhonker, Y.; Shivatzki, S.; Geiger, T.; Avraham, K.B.; Shamir, R. Reduced changes in protein compared to mRNA levels across non-proliferating tissues. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Barger, J.L.; Edwards, M.G.; Braun, K.H.; O’Connor, C.E.; Prolla, T.A.; Weindruch, R. Dynamic regulation of PGC-1alpha localization and turnover implicates mitochondrial adaptation in calorie restriction and the stress response. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastone, A.; Fumagalli, E.; Bigini, P.; Perini, P.; Bernardinello, D.; Cagnotto, A.; Mereghetti, I.; Curti, D.; Salmona, M.; Mennini, T. Proteomic profiling of cervical and lumbar spinal cord reveals potential protective mechanisms in the wobbler mouse, a model of motor neuron degeneration. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 5229–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Santos, M.; de Carvalho, M. Profiling tofersen as a treatment of superoxide dismutase 1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2024, 24, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.R.; Waldenstrom, J. With Reference to Reference Genes: A Systematic Review of Endogenous Controls in Gene Expression Studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Duff, K. A technique for serial collection of cerebrospinal fluid from the cisterna magna in mouse. J. Vis. Exp. 2008, 21, 960. [Google Scholar]

- Benatar, M.; Ostrow, L.W.; Lewcock, J.W.; Bennett, F.; Shefner, J.; Bowser, R.; Larkin, P.; Bruijn, L.; Wuu, J. Biomarker Qualification for Neurofilament Light Chain in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Theory and Practice. Ann. Neurol. 2024, 95, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, N.; Morsch, M.; Ghazanfari, N.; Cole, L.; Visvanathan, A.; Leamey, C.; Phillips, W.D. The neuromuscular junction: Measuring synapse size, fragmentation and changes in synaptic protein density using confocal fluorescence microscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 94, 52220. [Google Scholar]

- Pun, S.; Sigrist, M.; Santos, A.F.; Ruegg, M.A.; Sanes, J.R.; Jessell, T.M.; Arber, S.; Caroni, P. An intrinsic distinction in neuromuscular junction assembly and maintenance in different skeletal muscles. Neuron 2002, 34, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ryu, I.S.; Ha, D.-I.; Jung, Y.-J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, I.; Lim, Y.N.; Min, H.S.; Kim, S.H.; Yoon, I.; Cho, H.-J.; et al. Modulation of the miR-485-3p/PGC-1α Pathway by ASO-Loaded Nanoparticles Attenuates ALS Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020615

Ryu IS, Ha D-I, Jung Y-J, Lee HJ, Kim I, Lim YN, Min HS, Kim SH, Yoon I, Cho H-J, et al. Modulation of the miR-485-3p/PGC-1α Pathway by ASO-Loaded Nanoparticles Attenuates ALS Pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020615

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyu, In Soo, Dae-In Ha, Yeon-Joo Jung, Hyo Jin Lee, Insun Kim, Yu Na Lim, Hyun Su Min, Seung Hyun Kim, Ilsang Yoon, Hyun-Jeong Cho, and et al. 2026. "Modulation of the miR-485-3p/PGC-1α Pathway by ASO-Loaded Nanoparticles Attenuates ALS Pathogenesis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020615

APA StyleRyu, I. S., Ha, D.-I., Jung, Y.-J., Lee, H. J., Kim, I., Lim, Y. N., Min, H. S., Kim, S. H., Yoon, I., Cho, H.-J., & Ryu, J.-H. (2026). Modulation of the miR-485-3p/PGC-1α Pathway by ASO-Loaded Nanoparticles Attenuates ALS Pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020615