The Adipokine Axis in Heart Failure: Linking Obesity, Sarcopenia and Cardiac Dysfunction in HFpEF

Abstract

1. Introduction

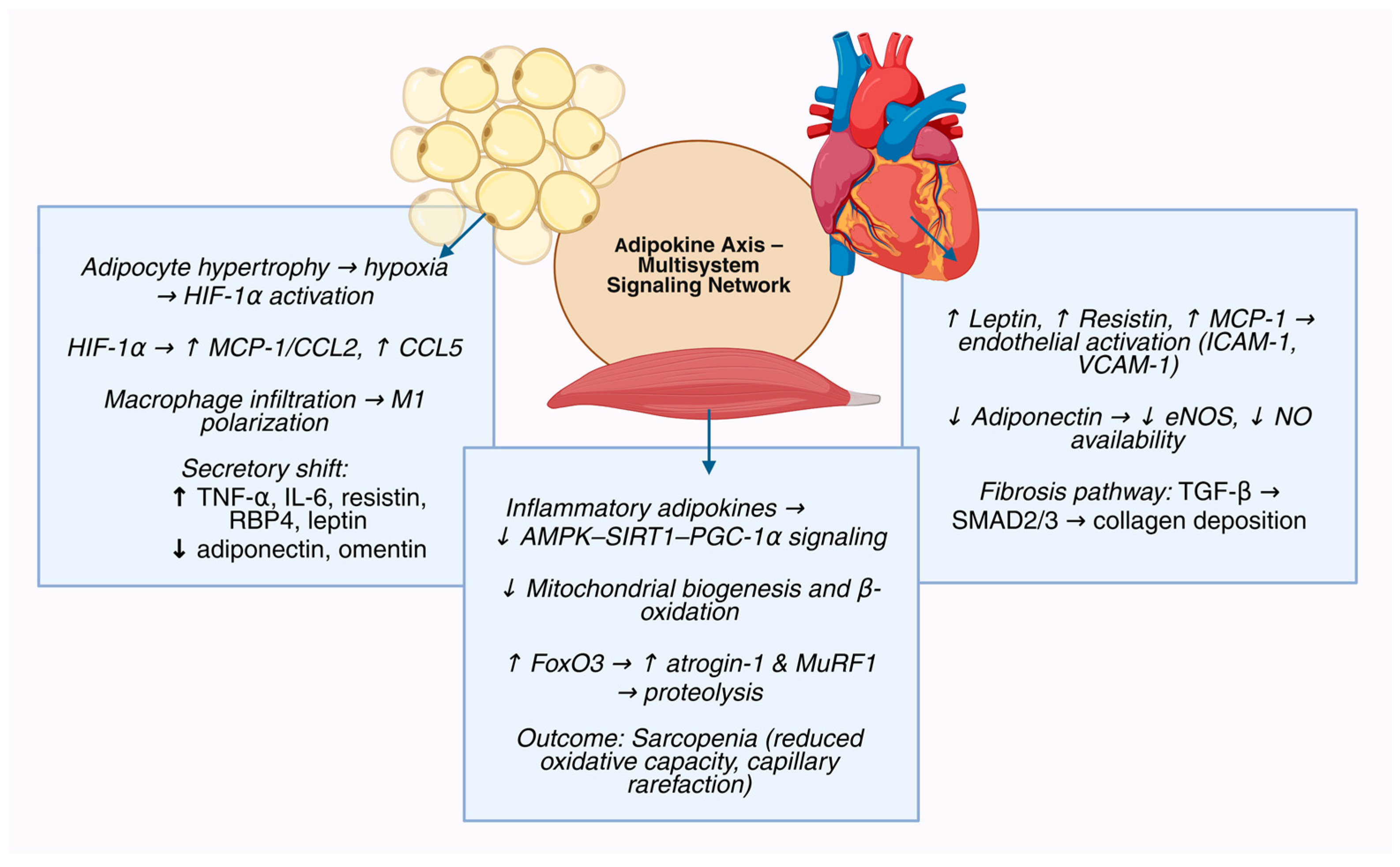

2. The Adipokine Axis as a Multisystem Regulatory Network

3. The Adipokine Axis as the Integrator of Obesity, Sarcopenia, and HFpEF—An Adipokine-Centric Synthesis

3.1. Homeostatic Adipokines That Preserve Endothelial–Myocardial–Myocellular Resilience

3.2. Stress-Inducible Adipokines That Sense Energetic Strain and Attempt Rescue

3.3. Injurious Adipokines That Enforce Endothelial Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Anabolic Failure

3.4. Controversies and Evidence Gaps

3.5. Translational Limitations: Rodent vs. Human Adipokine Biology

4. Translational Implications: From Biomarkers to Therapeutic Targets

4.1. The Adipokine Signature as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Framework

4.2. Leptin Resistance and the Therapeutic Paradox in Sarcopenic Heart Failure

4.3. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Rebalancing the Adipokine Network

4.4. Targeting Specific Adipokine Pathways: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

4.5. Multi-Modal Biomarker Integration and Precision Medicine Approaches

4.6. Challenges and Future Directions in Adipokine-Based Therapeutics

4.7. The Adiponectin Paradox: Implications for Therapeutic Development

4.8. Implications for Clinical Practice and Guidelines

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pavlović, N.; Križanac, M.; Kumrić, M.; Vukojević, K.; Rušić, D.; Božić, J. Obesity in reproduction: Mechanisms from fertilization to post-uterine development (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komici, K.; Dello Iacono, A.; De Luca, A.; Bencivenga, L.; Rengo, G.; Perrone-Filardi, P.; Formisano, R.; Guerra, G. Adiponectin and sarcopenia: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 576619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. The Adipokine Hypothesis of Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. A Novel Framework to Explain Pathogenesis and Guide Treatment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorakis, N.; Kreouzi, M.; Hitas, C.; Anagnostou, D.; Nikolaou, M. Adipokines and cardiometabolic Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A state-of-the-art review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.; Koka, S.; Boini, K.M. Understanding the role of adipokines in cardiometabolic dysfunction: A review of current knowledge. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Kitzman, D.W. Obesity-related heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: The pathophysiologic and clinical implications of a prevalent phenotype. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Proenca, R.; Maffei, M.; Barone, M.; Leopold, L.; Friedman, J.M. Positional cloning of the mouse obese (ob) gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994, 372, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, P.E.; Williams, S.; Fogliano, M.; Baldini, G.; Lodish, H.F. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 26746–26749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Okubo, K.; Shimomura, I.; Funahashi, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Matsubara, K. cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose-specific collagen-like factor, adiponectin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 221, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Ito, Y.; Tsuchida, A.; Yokomizo, T.; Kita, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Hara, K.; Tsunoda, M.; et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature 2003, 423, 762–769, Correction in Nature 2004, 431, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, T.; Yamauchi, T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Feng, W.; Lai, J.; Yuan, D.; Xiao, W.; Li, Y. Role of adipokines in sarcopenia. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2023, 136, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zou, F.; Zhang, X.; Qian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X.; Zou, J. Causal effect of central obesity on left ventricular structure and function in preserved EF population: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 9, 1103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savji, N.; Meijers, W.C.; Bartz, T.M.; Bhambhani, V.; Cushman, M.; Nayor, M.; Kizer, J.R.; Sarma, A.; Blaha, M.J.; Gansevoort, R.T.; et al. The Association of Obesity and Cardiometabolic Traits With Incident HFpEF and HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, D.L.; Bohmke, N.; Billingsley, H.E.; Carbone, S. Sarcopenic Obesity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 558271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. Emerging role of adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and insulin resistance. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlman, I.; Kaaman, M.; Olsson, T.; Tan, G.D.; Bickerton, A.S.; Wåhlén, K.; Andersson, J.; Nordström, E.A.; Blomqvist, L.; Sjögren, A.; et al. A unique role of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 among chemokines in adipose tissue of obese subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 5834–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartipy, P.; Loskutoff, D.J. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7265–7270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavazos, A.E.; Ermetici, F.; Coman, C.; Corsi, M.M.; Morricone, L.; Ambrosi, B. Influence of epicardial adipose tissue and adipocytokine levels on cardiac abnormalities in visceral obesity. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 121, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Park, J.H.; Kang, J.H.; Kawada, T.; Yu, R.; Han, I.S. Chemokine and chemokine receptor gene expression in the mesenteric adipose tissue of KKAy mice. Cytokine 2009, 46, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, G.; Bianco, A.C. Epicardial adipose tissue: Emerging physiological, pathophysiological and clinical features. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, C.; Chen, S.; Unger, A.; Korkmaz, H.I.; De Keulenaer, G.W.; Tschöpe, C.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Musters, R.; Niessen, H.W.M.; Linke, W.A.; et al. Myocardial microvascular inflammatory endothelial activation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, T.; Zhang, L.; Zalewski, A.; Mannion, J.D.; Diehl, J.T.; Arafat, H.; Sarov-Blat, L.; O’Brien, S.; Keiper, E.A.; Johnson, A.G.; et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation 2003, 108, 2460–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Shargill, N.S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-α: Direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993, 259, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steppan, C.M.; Bailey, S.T.; Bhat, S.; Brown, E.J.; Banerjee, R.R.; Wright, C.M.; Patel, H.R.; Ahima, R.S.; Lazar, M.A. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature 2001, 409, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Graham, T.E.; Mody, N.; Preitner, F.; Peroni, O.D.; Zabolotny, J.M.; Kotani, K.; Quadro, L.; Kahn, B.B. Serum retinol-binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2005, 436, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Kihara, S.; Arita, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Maeda, K.; Kuriyama, H.; Hotta, K.; Nishida, M.; Takahashi, M.; Muraguchi, M.; et al. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived plasma protein, inhibits endothelial NF-kappaB signaling through a cAMP-dependent pathway. Circulation 2000, 102, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castan-Laurell, I.; Dray, C.; Attané, C.; Duparc, T.; Knauf, C.; Valet, P. Apelin, diabetes, and obesity. Endocrine 2011, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Batista, C.M.; Yang, R.-Z.; Lee, M.-J.; Glynn, N.M.; Yu, D.-Z.; Pray, J.; Ndubuizu, K.; Patil, S.; Schwartz, A.; Kligman, M.; et al. Omentin plasma levels and gene expression are decreased in obesity. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhong, N.; Wen, D.; Liu, L. Multifaced roles of adipokines in endothelial cell function. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1490143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoumianakis, I.; Antoniades, C. Impaired vascular redox signaling in the vascular complications of obesity and diabetes mellitus. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Xia, N. The interplay between adipose tissue and vasculature: Role of oxidative stress in obesity. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 650214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbély, A.; Falcao-Pires, I.; van Heerebeek, L.; Hamdani, N.; Edes, I.; Gavina, C.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Bronzwaer, J.G.F.; Papp, Z.; van der Velden, J.; et al. Hypophosphorylation of the Stiff N2B titin isoform raises cardiomyocyte resting tension in failing human myocardium. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Kanisicak, O.; Prasad, V.; Correll, R.N.; Fu, X.; Schips, T.; Vagnozzi, R.J.; Liu, R.; Huynh, T.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Fibroblast-specific TGF-β-Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3770–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology 2008, 23, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Feige, J.N.; Lagouge, M.; Noriega, L.; Milne, J.C.; Elliott, P.J.; Puigserver, P.; Auwerx, J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 2009, 458, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, Í.M.P.; Argilés, J.M.; Rueda, R.; Ramírez, M.; Pedrosa, J.M.L. Skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction in obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus: Myocellular mechanisms involved. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2025, 26, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dray, C.; Knauf, C.; Daviaud, D.; Waget, A.; Boucher, J.; Buléon, M.; Cani, P.D.; Attané, C.; Guigné, C.; Carpéné, C.; et al. Apelin stimulates glucose utilization in normal and obese insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkateshvaran, A.; Faxen, U.L.; Hage, C.; Michaëlsson, E.; Svedlund, S.; Saraste, A.; Beussink-Nelson, L.; Lagerstrom Fermer, M.; Gan, L.-M.; Tromp, J.; et al. Association of epicardial adipose tissue with proteomics, coronary flow reserve, cardiac structure and function, and quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Insights from the PROMIS-HFpEF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.-Z.; Lee, M.-J.; Hu, H.; Pray, J.; Wu, H.-B.; Hansen, B.C.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Fried, S.K.; McLenithan, J.C.; Gong, D.-W. Identification of omentin as a novel depot-specific adipokine in human adipose tissue: Possible role in modulating insulin action. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 290, E1253–E1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, M.Y.; Maleki, S.; Oghenemaro, E.F.; Singh, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Alkhayyat, A.H.; Sapaev, I.B.; Kaur, P.; Shirsalimi, N.; Nagarwal, A. Omentin-1 as a promising biomarker and therapeutic target in hypertension and heart failure: A comprehensive review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 11145–11160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Higuchi, A.; Ohashi, K.; Oshima, Y.; Gokce, N.; Shibata, R.; Akasaki, Y.; Shimono, A.; Walsh, K. Sfrp5 is an anti-inflammatory adipokine that modulates metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Science 2010, 329, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, M.; Herder, C.; Kempf, K.; Erlund, I.; Martin, S.; Koenig, W.; Sundvall, J.; Bidel, S.; Kuha, S.; Roden, M.; et al. Sfrp5 correlates with insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Sano, S.; Fuster, J.J.; Kikuchi, R.; Shimizu, I.; Ohshima, K.; Katanasaka, Y.; Ouchi, N.; Walsh, K. Secreted frizzled-related protein 5 diminishes cardiac inflammation and protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 2566–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Du, Y.; Ji, Q.; Dong, R.; Cao, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Zeng, M.; Chen, H.; Zhu, X.; et al. Expression of Sfrp5/Wnt5a in human epicardial adipose tissue and their relationship with coronary artery disease. Life Sci. 2020, 245, 117338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Gong, W.; Nie, S. Secreted frizzled-related protein 5 protects against cardiac rupture and improves cardiac function through inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 682409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, I.; Woo, D.-C.; Pack, C.-G.; Sung, Y.H.; Baek, I.-J.; Jung, C.H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Ha, C.H.; et al. Angiogenic adipokine C1q-TNF-related protein 9 ameliorates myocardial infarction via histone deacetylase 7-mediated MEF2 activation. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq0898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Qu, W.; Zhang, T.; Feng, J.; Dong, X.; Nie, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Peng, C.; Ke, X. C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-9 is a novel vasculoprotective cytokine that restores high glucose-suppressed endothelial progenitor cell functions by activating the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e030054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Niu, Q.; Tang, S.; Jiang, Y. Association between circulating CTRP9 levels and coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, D.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Wei, X. CTRP9 prevents atherosclerosis progression through changing autophagic status of macrophages by activating USP22 mediated-de-ubiquitination on Sirt1 in vitro. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2024, 584, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, M. Hypermethylation of the CTRP9 promoter region promotes Hcy induced VSMC lipid deposition and foam cell formation via negatively regulating ER stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Li, J.; Lei, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, D.; Zuo, A.; Li, L.; Guo, Y. Knockout of C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-9 aggravates cardiac fibrosis in diabetic mice by regulating YAP-mediated autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1407883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planavila, A.; Redondo-Angulo, I.; Villarroya, F. FGF21 and cardiac physiopathology. Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhu, Z.; Xue, M.; Yi, X.; Liang, J.; Niu, C.; Chen, G.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 protects the heart from angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction via SIRT1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Gu, J. Cardioprotective effects of fibroblast growth factor 21 against doxorubicin-induced toxicity via the SIRT1/LKB1/AMPK pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaga, H.; Koitabashi, N.; Iso, T.; Matsui, H.; Obokata, M.; Kawakami, R.; Murakami, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Kurabayashi, M. Activation of cardiac AMPK-FGF21 feed-forward loop in acute myocardial infarction: Role of adrenergic overdrive and lipolysis byproducts. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.-H.; Huang, P.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Leu, H.-B.; Huang, C.-C.; Chen, J.-W.; Lin, S.-J. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 is associated with diastolic dysfunction in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.; McClelland, R.L.; Allison, M.A.; Szklo, M.; Rye, K.-A.; Ong, K.L. The association of circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 levels with incident heart failure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Metabolism 2023, 143, 155535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, M.; Clemmensen, C.; Sjøberg, K.A.; Carl, C.S.; Jeppesen, J.F.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.P.; Kiens, B.; Richter, E.A. Exercise increases circulating GDF15 in humans. Mol. Metab. 2018, 9, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Alvarez-Guaita, A.; Melvin, A.; Rimmington, D.; Dattilo, A.; Miedzybrodzka, E.L.; Cimino, I.; Maurin, A.-C.; Roberts, G.P.; Meek, C.L.; et al. GDF15 provides an endocrine signal of nutritional stress in mice and humans. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 707–718.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.M.Y.; Santhanakrishnan, R.; Chong, J.P.C.; Chen, Z.; Tai, B.C.; Liew, O.W.; Ng, T.P.; Ling, L.H.; Sim, D.; Leong, K.T.; et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 in heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction: GDF15inHFpEF vs. HFrEF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, D.; Yan, X.; Bai, X.; Tian, A.; Gao, Y.; Li, J. Prognostic value of Growth differentiation factors 15 in Acute heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2023, 10, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, D.; Matsuoka, Y.; Nakatani, D.; Okada, K.; Sunaga, A.; Kida, H.; Sato, T.; Kitamura, T.; Tamaki, S.; Seo, M.; et al. Role and prognostic value of growth differentiation factor 15 in patient of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Insights from the PURSUIT-HFpEF registry. Open Heart 2025, 12, e003008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempf, T.; Eden, M.; Strelau, J.; Naguib, M.; Willenbockel, C.; Tongers, J.; Heineke, J.; Kotlarz, D.; Xu, J.; Molkentin, J.D.; et al. The transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member growth-differentiation factor-15 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollert, K.C.; Kempf, T.; Wallentin, L. Growth differentiation factor 15 as a biomarker in cardiovascular disease. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Martucci, M.; Mosconi, G.; Chiariello, A.; Cappuccilli, M.; Totti, V.; Santoro, A.; Franceschi, C.; Salvioli, S. GDF15 plasma level is inversely associated with level of physical activity and correlates with markers of inflammation and muscle weakness. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Byun, J.; Zhai, P.; Ikeda, Y.; Oka, S.; Sadoshima, J. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, an intermediate of NAD+ synthesis, protects the heart from ischemia and reperfusion. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-P.; Yamamoto, T.; Oka, S.; Sadoshima, J. The function of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase in the heart. DNA Repair 2014, 23, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, M.; Akazawa, H.; Oka, T.; Yabumoto, C.; Kudo-Sakamoto, Y.; Kamo, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Yagi, H.; Naito, A.T.; Lee, J.-K.; et al. Monocyte-derived extracellular Nampt-dependent biosynthesis of NAD+ protects the heart against pressure overload. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Sangwung, P.; Fujioka, H.; Zhang, L.; Liao, X. Short-term administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide preserves cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis and prevents heart failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2017, 112, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, M.; Sedej, S.; Kroemer, G. NAD+ metabolism in cardiac health, aging, and disease. Circulation 2021, 144, 1795–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Oka, S.-I.; Imai, N.; Huang, C.-Y.; Ralda, G.; Zhai, P.; Ikeda, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Sadoshima, J. Both gain and loss of Nampt function promote pressure overload-induced heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317, H711–H725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, P.; Wu, J.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Korde, A.; Ye, L.; Lo, J.C.; Rasbach, K.A.; Boström, E.A.; Choi, J.H.; Long, J.Z.; et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 2012, 481, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, S.; Pan, Y. The emerging roles of irisin in vascular calcification. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1337995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, I.; Coccurello, R. Irisin: A multifaceted hormone bridging exercise and disease pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestrini, A.; Bruno, C.; Vergani, E.; Venuti, A.; Favuzzi, A.M.R.; Guidi, F.; Nicolotti, N.; Meucci, E.; Mordente, A.; Mancini, A. Circulating irisin levels in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezin, A.E.; Berezina, T.A.; Novikov, E.V.; Berezin, O.O. Serum levels of irisin are positively associated with improved cardiac function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A.A.; Lichtenauer, M.; Boxhammer, E.; Fushtey, I.M.; Berezin, A.E. Serum levels of irisin predict cumulative clinical outcomes in heart failure patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 922775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A.A.; Fushtey, I.M.; Pavlov, S.V.; Berezin, A.E. Predictive value of serum irisin for chronic heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol. Biomed. 2022, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen-Telders, C.; Eringa, E.C.; de Groot, J.R.; de Man, F.S.; Handoko, M.L. The role of epicardial adipose tissue remodelling in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woerden, G.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Westenbrink, B.D.; de Boer, R.A.; Rienstra, M.; Gorter, T.M. Connecting epicardial adipose tissue and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Mechanisms, management and modern perspectives. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 2238–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Martínez, E.; Jurado-López, R.; Valero-Muñoz, M.; Bartolomé, M.V.; Ballesteros, S.; Luaces, M.; Briones, A.M.; López-Andrés, N.; Miana, M.; Cachofeiro, V. Leptin induces cardiac fibrosis through galectin-3, mTOR and oxidative stress: Potential role in obesity. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 1104–1114; discussion 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Zhu, D.; Tian, G. Epicardial adipose tissue-derived Leptin promotes myocardial injury in metabolic syndrome rats through PKC/NADPH oxidase/ROS pathway. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norseen, J.; Hosooka, T.; Hammarstedt, A.; Yore, M.M.; Kant, S.; Aryal, P.; Kiernan, U.A.; Phillips, D.A.; Maruyama, H.; Kraus, B.J. Retinol-binding protein 4 inhibits insulin signaling in adipocytes by inducing proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase- and toll-like receptor 4-dependent and retinol-independent mechanism. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 2010–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Yan, X.; Xu, C.; Fang, Y.; Ma, M. Association between circulating retinol-binding protein 4 and adverse cardiovascular events in stable coronary artery disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 829347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Sunaga, H.; Sorimachi, H.; Yoshida, K.; Kato, T.; Kurosawa, K.; Nagasaka, T.; Koitabashi, N.; Iso, T.; Kurabayashi, M.; et al. Pathophysiological role of fatty acid-binding protein 4 in Asian patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 4256–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.Z.; Prestes, P.R.; Byars, S.G.; Ritchie, S.C.; Würtz, P.; Patel, S.K.; Booth, S.A.; Rana, I.; Minoda, Y.; Berzins, S.P.; et al. Experimental and human evidence for lipocalin-2 (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin [NGAL]) in the development of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, D.W.; Hwang, C.G.; Han, M.; Rhee, H.; Song, S.H.; Seong, E.Y.; Lee, S.B. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is independently associated with left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Lin, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, N.; Cai, K. Prognostic value of serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in acute heart failure: A meta-analysis. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Leu, H.-B.; Wu, Y.-W.; Tseng, W.-K.; Lin, T.-H.; Yeh, H.-I.; Chang, K.-C.; Wang, J.-H.; Yin, W.-H.; Wu, C.-C.; et al. Prognostic utility of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) levels for cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary artery disease treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Qian, Z.; Lu, X. Serum chemerin as a novel prognostic indicator in chronic heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Choi, H.Y.; Yang, S.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Seo, J.A.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, N.H.; Choi, K.M.; Choi, D.S.; Baik, S.H. Circulating chemerin level is independently correlated with arterial stiffness. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2012, 19, 59–66; discussion 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macvanin, M.T.; Rizzo, M.; Radovanovic, J.; Sonmez, A.; Paneni, F.; Isenovic, E.R. Role of chemerin in cardiovascular diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, H.; Al-Darraji, A.; Abo-Aly, M.; Peng, H.; Shokri, E.; Chelvarajan, L.; Donahue, R.R.; Levitan, B.M.; Gao, E.; Hernandez, G.; et al. Autotaxin inhibition reduces cardiac inflammation and mitigates adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020, 149, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Han, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J. Lysophosphatidic acid is associated with cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy by suppressing autophagy via the LPA3/AKT/mTOR pathway. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, T.; Okumura, T.; Hiraiwa, H.; Mizutani, T.; Kimura, Y.; Kazama, S.; Shibata, N.; Oishi, H.; Kuwayama, T.; Kondo, T.; et al. Serum autotaxin as a novel prognostic marker in patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, A.; Fernando, J.J.; Kienesberger, P.C. Lysophosphatidic acid metabolism and signaling in heart disease. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 102, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.; Kienesberger, P.C. Autotaxin-LPA-LPP3 axis in energy metabolism and metabolic disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Ruifrok, W.P.T.; Meissner, M.; Bos, E.M.; van Goor, H.; Sanjabi, B.; van der Harst, P.; Pitt, B.; Goldstein, I.J.; Koerts, J.A.; et al. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of galectin-3 prevents cardiac remodeling by interfering with myocardial fibrogenesis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, F.; Holzendorf, V.; Wachter, R.; Nolte, K.; Schmidt, A.G.; Kraigher-Krainer, E.; Düngen, H.-D.; Tschöpe, C.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Halle, M.; et al. Galectin-3 in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Results from the Aldo-DHF trial: Galectin-3 in patients with HFpEF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborska, B.; Sikora-Frąc, M.; Smarż, K.; Pilichowska-Paszkiet, E.; Budaj, A.; Sitkiewicz, D.; Duvinage, A.; Unkelbach, I.; Düngen, H.-D.; Tschöpe, C.; et al. The role of galectin-3 in heart failure-the diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic potential-where do we stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, K.; Irion, C.I.; Takeuchi, L.M.; Ding, W.; Lambert, G.; Eisenberg, T.; Sukkar, S.; Granzier, H.L.; Methawasin, M.; Lee, D.I.; et al. Osteopontin promotes left ventricular diastolic dysfunction through a mitochondrial pathway. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2705–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenga, Y.; Koh, A.; Perera, A.S.; McCulloch, C.A.; Sodek, J.; Zohar, R. Osteopontin expression is required for myofibroblast differentiation. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamazhakypov, A.; Sartmyrzaeva, M.; Sarybaev, A.S.; Schermuly, R.; Sydykov, A. Clinical and molecular implications of osteopontin in heart failure. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 3573–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Williams, H.; Jackson, M.L.; Johnson, J.L.; George, S.J. WISP-1 regulates cardiac fibrosis by promoting cardiac fibroblasts’ activation and collagen processing. Cells 2024, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchetta, I.; Cimini, F.A.; Capoccia, D.; De Gioannis, R.; Porzia, A.; Mainiero, F.; Bertoccini, L.; De Bernardinis, M.; Leonetti, F.; Cavallo, M.G. WISP1 is a marker of systemic and adipose tissue inflammation in dysmetabolic subjects with or without type 2 diabetes. J. Endocr. Soc. 2017, 1, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X. Emerging role of CCN family proteins in fibrosis. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 4195–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Oladipupo, S.S. An overview of CCN4 (WISP1) role in human diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.H.; Seliger, S.L.; Christenson, R.; Gottdiener, J.S.; Psaty, B.M.; deFilippi, C.R. Soluble ST2 for prediction of heart failure and cardiovascular death in an elderly, community-dwelling population. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccardi, M.; Myhre, P.L.; Zelniker, T.A.; Metra, M.; Januzzi, J.L.; Inciardi, R.M. Soluble ST2 in heart failure: A clinical role beyond B-type natriuretic peptide. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyanik, M.; Cinar, A.; Gedikli, O.; Tuna, T.; Avci, B. Soluble ST2 as a biomarker for predicting right ventricular dysfunction in acute pulmonary embolism. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanpaa, L.; Sipila, T.; Leppanen, V.-M.; Gautam, P.; Nurmi, H.; Jacquemet, G.; Eklund, L.; Ivaska, J.; Alitalo, K.; Saharinen, P. Endothelial destabilization by angiopoietin-2 via integrin β1 activation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorin, E.; Labbé, P.; Lambert, M.; Mury, P.; Dagher, O.; Miquel, G.; Thorin-Trescases, N. Angiopoietin-like proteins: Cardiovascular biology and therapeutic targeting for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Can. J. Cardiol. 2023, 39, 1736–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Miquel, G.; Cagnone, G.; Mury, P.; Villeneuve, L.; Lesage, F.; Thorin-Trescases, N.; Thorin, E. Targeting angiopoietin like-2 positive senescent cells improves cognitive impairment in adult male but not female atherosclerotic LDLr−/−;hApoB100+/+ mice. GeroScience 2025, 47, 6999–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varricchi, G.; Poto, R.; Ferrara, A.L.; Gambino, G.; Marone, G.; Rengo, G.; Loffredo, S.; Bencivenga, L. Angiopoietins, vascular endothelial growth factors and secretory phospholipase A2 in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 106, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Miyata, K.; Kadomatsu, T.; Horiguchi, H.; Fukushima, H.; Tohyama, S.; Ujihara, Y.; Okumura, T.; Yamaguchi, S.; Zhao, J.; et al. ANGPTL2 activity in cardiac pathologies accelerates heart failure by perturbing cardiac function and energy metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, A.P.; Hijazi, Z.; Lindbäck, J.; Connolly, S.J.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Kastner, P.; Ziegler, A.; Alexander, J.H.; Granger, C.B.; Lopes, R.D.; et al. Plasma angiopoietin-2 and its association with heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2023, 25, euad200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, F.R.; Shah, S.J. The future of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Deep phenotyping for targeted therapeutics: Deep phenotyping for targeted therapeutics. Herz 2022, 47, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, R.A.; Nayor, M.; deFilippi, C.R.; Enserro, D.; Bhambhani, V.; Kizer, J.R.; Blaha, M.J.; Brouwers, F.P.; Cushman, M.; Lima, J.A.C.; et al. Association of cardiovascular biomarkers with incident heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.-P.; Kleber, M.E.; Koller, L.; Sulzgruber, P.; Scharnagl, H.; Delgado, G.; Goliasch, G.; März, W.; Niessner, A. Prognostic significance of tPA/PAI-1 complex in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.P.; Kaur, J.; Mohan, G.; Kukreja, S. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 levels in heart Failure patients: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2025, 19, BC01–BC05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellan, B.; Sutton, N.R.; Hofmann Bowman, M.A. S100/RAGE-mediated inflammation and modified cholesterol lipoproteins as mediators of osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Deng, H. Pathophysiology of RAGE in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 931473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chusyd, D.E.; Wang, D.; Huffman, D.M.; Nagy, T.R. Relationships between Rodent White Adipose Fat Pads and Human White Adipose Fat Depots. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börgeson, E.; Boucher, J.; Hagberg, C.E. Of mice and men: Pinpointing species differences in adipose tissue biology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1003118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.L.; Lau, W.B. Cardiovascular Adiponectin Resistance: The Critical Role of Adiponectin Receptor Modification. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallam, L.S.; da Silva, A.A.; Hall, J.E. Melanocortin-4 receptor mediates chronic cardiovascular and metabolic actions of leptin. Hypertension 2006, 48, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, R.; Bertolet, M.; Singh, P.; Brooks, M.M.; Pratley, R.E.; Frye, R.L.; Mooradian, A.D.; Rutter, M.K.; Calvin, A.D.; Chaitman, B.R.; et al. Prognostic value of adipokines in predicting cardiovascular outcome: Explaining the obesity paradox. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.-W.; Ok, M.; Lee, S.-K. Leptin as a key between obesity and cardiovascular disease. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 29, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Muñoz, M.; Saw, E.L.; Cooper, H.; Pimentel, D.R.; Sam, F. White Adipose Tissue in Obesity-Associated HFpEF: Insights From Mice and Humans. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2025, 10, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Ramos, L.; Scherer, P.E. Adipose Tissue Stress-Related Changes in Mice and Humans with HFpEF. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2025, 10, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, P.; Huang, L.; Peng, X.; Yue, J.; Ge, N. Comorbidities and incidence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laparra, A.; Tricot, S.; Le Van, M.; Damouche, A.; Gorwood, J.; Vaslin, B.; Favier, B.; Benoist, S.; Ho Tsong Fang, R.; Bosquet, N.; et al. The Frequencies of Immunosuppressive Cells in Adipose Tissue Differ in Human, Non-human Primate, and Mouse Models. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chella Krishnan, K.; Vergnes, L.; Acín-Pérez, R.; Stiles, L.; Shum, M.; Ma, L.; Mouisel, E.; Pan, C.; Moore, T.M.; Péterfy, M.; et al. Sex-specific genetic regulation of adipose mitochondria and metabolic syndrome by Ndufv2. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, P.; Sahakyan, K.R.; Davison, D.E.; Sert-Kuniyoshi, F.H.; Romero-Corral, A.; Swain, J.M.; Jensen, M.D.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Kara, T.; et al. Differential effects of leptin on adiponectin expression with weight gain versus obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withaar, C.; Lam, C.S.P.; Schiattarella, G.G.; de Boer, R.A.; Meems, L.M.G. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in humans and mice: Embracing clinical complexity in mouse models. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4420–4430, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1940. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Tian, S.; Liang, W.; Wu, L. Association between omentin-1 and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in Chinese elderly patients. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 47, e24181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, A.L.; Zhang, M.H.; Ku, I.A.; Na, B.; Schiller, N.B.; Whooley, M.A. Adiponectin is associated with increased mortality and heart failure in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: Data from the Heart and Soul Study. Atherosclerosis 2012, 220, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Huang, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Tao, J. Association between elevated adiponectin level and adverse outcomes in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, e8416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, T.; de Mutsert, R.; Lamb, H.J.; van Dijk, K.W.; le Cessie, S.; Rosendaal, F.R.; J Wouter Jukema, J.W.; Trompet, S. Mendelian randomization study of the relation between adiponectin and heart function, unravelling the paradox. Peptides 2021, 146, 170664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agra-Bermejo, R.M.; Cacho-Antonio, C.; Gonzalez-Babarro, E.; Rozados-Luis, A.; Couselo-Seijas, M.; Gómez-Otero, I.; Varela-Román, A.; López-Canoa, J.N.; Gómez-Rodríguez, I.; Pata, M.; et al. A new biomarker tool for risk stratification in “de novo” acute heart failure (OROME). Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 736245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.K.; Cave, B.J.; Oksanen, L.J.; Tzameli, I.; Bjørbaek, C.; Flier, J.S. Enhanced leptin sensitivity and attenuation of diet-induced obesity in mice with haploinsufficiency of Socs3. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, H.; Hanada, R.; Hanada, T.; Aki, D.; Mashima, R.; Nishinakamura, H.; Torisu, T.; Chien, K.R.; Yasukawa, H.; Yoshimura, A. Socs3 deficiency in the brain elevates leptin sensitivity and confers resistance to diet-induced obesity. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bence, K.K.; Delibegovic, M.; Xue, B.; Gorgun, C.Z.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Neel, B.G.; Kahn, B.B. Neuronal PTP1B regulates body weight, adiposity and leptin action. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 917–924, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej-Sobczak, D.; Sobczak, Ł.; Łączkowski, K.Z. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B): A comprehensive review of its role in pathogenesis of human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Yu, Y.; Zides, C.G.; Beyak, M.J. Mechanisms of reduced leptin-mediated satiety signaling during obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gava, F.N.; da Silva, A.A.; Dai, X.; Harmancey, R.; Ashraf, S.; Omoto, A.C.M.; Salgado, M.C.; Moak, S.P.; Li, X.; Hall, J.E.; et al. Restoration of cardiac function after myocardial infarction by long-term activation of the CNS Leptin-melanocortin system. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omoto, A.C.M.; do Carmo, J.M.; Nelson, B.; Aitken, N.; Dai, X.; Moak, S.; Flynn, E.; Wang, Z.; Mouton, A.J.; Li, X.; et al. Central nervous system actions of Leptin improve cardiac function after ischemia-reperfusion: Roles of sympathetic innervation and sex differences. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e027081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, K.; van den Akker, E.; Argente, J.; Bahm, A.; Chung, W.K.; Connors, H.; De Waele, K.; Farooqi, I.S.; Gonneau-Lejeune, J.; Gordon, G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of setmelanotide, an MC4R agonist, in individuals with severe obesity due to LEPR or POMC deficiency: Single-arm, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.H.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiborod, M.N.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Borlaug, B.A.; Butler, J.; Rasmussen, S.; Davies, M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kitzman, D.W.; Lindegaard, M.L.; Møller, D.V.; et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Zile, M.R.; Kramer, C.M.; Baum, S.J.; Litwin, S.E.; Menon, V.; Ge, J.; Weerakkody, G.J.; Ou, Y.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deanfield, J.; Verma, S.; Scirica, B.M.; Kahn, S.E.; Emerson, S.S.; Ryan, D.; Lingvay, I.; Colhoun, H.M.; Plutzky, J.; Kosiborod, M.N.; et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with obesity and prevalent heart failure: A prespecified analysis of the SELECT trial. Lancet 2024, 404, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Marso, S.P.; Ayers, C.R.; Lewis, B.; Oslica, R.; Francis, W.; Rodder, S.; Pandey, A.; Joshi, P.H. Effects of liraglutide on visceral and ectopic fat in adults with overweight and obesity at high cardiovascular risk: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrimmon, R.J.; Catarig, A.-M.; Frias, J.P.; Lausvig, N.L.; le Roux, C.W.; Thielke, D.; Lingvay, I. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide vs once-daily canagliflozin on body composition in type 2 diabetes: A substudy of the SUSTAIN 8 randomised controlled clinical trial. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zou, S.; Liu, X.; Wong, T.Y.P.; Zhang, X.; Xu, K.S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Zhou, Q.; et al. The effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on body composition in patients with type 2 diabetes, overweight or obesity: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1003, 177885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vest, A.R.; Chan, M.; Deswal, A.; Givertz, M.M.; Lekavich, C.; Lennie, T.; Litwin, S.E.; Parsly, L.; Rodgers, J.E.; Rich, M.W.; et al. Nutrition, obesity, and cachexia in patients with heart failure: A consensus Statement from the heart failure society of America scientific statements committee. J. Card. Fail. 2019, 25, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Liu, T.; Fu, F.; Cui, Z.; Lai, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Liu, F.; Kou, J.; Li, F. Omentin1 ameliorates myocardial ischemia-induced heart failure via SIRT3/FOXO3a-dependent mitochondrial dynamical homeostasis and mitophagy. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Lam, K.S.L.; Xu, A. The therapeutic potential of FGF21 in metabolic diseases: From bench to clinic. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada-Iwabu, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Iwabu, M.; Honma, T.; Hamagami, K.-I.; Matsuda, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tanabe, H.; Kimura-Someya, T.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 2013, 503, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Lund, L.H.; Rao, P.; Ghosh, R.; Warier, P.; Vaccaro, B.; Dahlström, U.; O’Connor, C.M.; Felker, G.M.; Desai, N.R.; et al. Machine learning methods improve prognostication, identify clinically distinct phenotypes, and detect heterogeneity in response to therapy in a large cohort of heart failure patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schipper, H.S.; de Jager, W.; van Dijk, M.E.A.; Meerding, J.; Zelissen, P.M.J.; Adan, R.A.; Prakken, B.J.; Kalkhoven, E. A multiplex immunoassay for human adipokine profiling. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.G.; Sivitz, W.I.; Morgan, D.A.; Walsh, S.A.; Mark, A.L. Sympathetic and cardiorenal actions of leptin. Hypertension 1997, 30, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bełtowski, J. Leptin and the regulation of endothelial function in physiological and pathological conditions: Leptin and endothelial function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 39, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lago, F.; Gómez, R.; Gómez-Reino, J.J.; Dieguez, C.; Gualillo, O. Adipokines as novel modulators of lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyer, L.G.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Foryst-Ludwig, A.; Kintscher, U.; Chennappan, S.; Kontaridis, M.I.; McKinsey, T.A. Modulating the secretome of fat to treat heart failure. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Kitzman, D.W.; Borlaug, B.A.; van Heerebeek, L.; Zile, M.R.; Kass, D.A.; Paulus, W.J. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A multiorgan roadmap: A multiorgan roadmap. Circulation 2016, 134, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Wharton, S.; Connery, L.; Alves, B.; Kiyosue, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías, J.P.; Davies, M.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Pérez Manghi, F.C.; Fernández Landó, L.; Bergman, B.K.; Liu, B.; Cui, X.; Brown, K.; SURPASS-2 Investigators. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, T.; Sloop, K.W.; Loghin, C.; Alsina-Fernandez, J.; Urva, S.; Bokvist, K.B.; Cui, X.; Briere, D.A.; Cabrera, O.; Roell, W.C.; et al. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol. Metab. 2018, 18, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, R.; Ouchi, N.; Ito, M.; Kihara, S.; Shiojima, I.; Pimentel, D.R.; Kumada, M.; Sato, K.; Schiekofer, S.; Ohashi, K.; et al. Adiponectin-mediated modulation of hypertrophic signals in the heart. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 1384–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.-J.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Gu, W.-J.; Aung, L.H.H. Adiponectin is associated with increased mortality in patients with already established cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2014, 63, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarale, M.G.; Fontana, A.; Trischitta, V.; Copetti, M.; Menzaghi, C. Circulating adiponectin levels are paradoxically associated with mortality rate. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 104, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizer, J.R.; Benkeser, D.; Arnold, A.M.; Mukamal, K.J.; Ix, J.H.; Zieman, S.J.; Siscovick, D.S.; Tracy, R.P.; Mantzoros, C.S.; deFilippi, C.R.; et al. Associations of total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in older persons: The Cardiovascular Health Study: The cardiovascular health study. Circulation 2012, 126, 2951–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J.; van der Meer, P.; Verma, S.; Patel, S.; Chinnakondepalli, K.M.; Borlaug, B.A.; Butler, J.; Kitzman, D.W.; Shah, S.J.; Harring, S.; et al. Semaglutide in obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and type 2 diabetes across baseline HbA1c levels (STEP-HFpEF DM): A prespecified analysis of heart failure and metabolic outcomes from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narumi, T.; Watanabe, T.; Kadowaki, S.; Kinoshita, D.; Yokoyama, M.; Honda, Y.; Otaki, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Takahashi, H.; Arimoto, T.; et al. Impact of serum omentin-1 levels on cardiac prognosis in patients with heart failure. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, N.; Naruse, M.; Usui, T.; Tagami, T.; Suganami, T.; Yamada, K.; Kuzuya, H.; Shimatsu, A.; Ogawa, Y. Leptin-to-adiponectin ratio as a potential atherogenic index in obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2488–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Haehling, S.; Ebner, N.; Dos Santos, M.R.; Springer, J.; Anker, S.D. Muscle wasting and cachexia in heart failure: Mechanisms and therapies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adipokine/Pathway | Primary Molecular Actions | Pathogenic Roles in Obesity–Sarcopenia–HFpEF | Translational and Clinical Implications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omentin-1 | Activates AMPK and Akt pathways; increases endothelial NO; improves insulin sensitivity; stimulates SIRT3/FOXO3a signaling | Reduced levels contribute to microvascular dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and impaired diastolic relaxation | Diagnostic biomarker (outperforms NT-proBNP in the elderly); AAV-mediated omentin-1 therapy improves LV function and reduces ischemia–reperfusion injury | [30,42,43,139,160] |

| Adiponectin | Activates AMPK and PPAR-α; enhances fatty acid oxidation; anti-inflammatory; improves NO bioavailability | Elevated levels paradoxically predict higher mortality and HF hospitalization; influenced by NT-proBNP-driven reverse causality | AdipoR agonists bypass circulating adiponectin; potential therapy for restoring metabolic–vascular coupling | [2,11,12,140,141,142,173,174] |

| GDF15 | Stress-induced cytokine; reflects mitochondrial dysfunction; regulates catabolic signaling via GFRAL | Elevated levels associated with diastolic stiffness, exercise intolerance, and increased mortality; a mechanistic bridge between muscle wasting and HFpEF | Strong prognostic biomarker; potential therapeutic target pending tissue-specific modulation strategies | [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| Leptin | Activates JAK/STAT and TGF-β1 pathways; promotes sympathetic activation; suppresses ghrelin; induces SOCS3 feedback inhibition | Hyperleptinemia drives myocardial fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction, and skeletal-muscle catabolism | Leptin-sensitizing strategies (SOCS3/PTP1B inhibition); central MC4R activation provides cardioprotection | [84,85,131,165,166] |

| Leptin Resistance Mechanisms | SOCS3 inhibits leptin receptor signaling; PTP1B dephosphorylates JAK2; impaired BBB transport reduces central leptin action | Sustained leptin elevation with reduced signaling effectiveness; contributes to catabolic muscle loss and metabolic inflammation | SOCS3/PTP1B inhibitors and MC4R agonists (e.g., setmelanotide) under investigation | [144,145,146,147,148] |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RA) | Reduce visceral and epicardial fat; increase adiponectin; decrease pro-inflammatory adipokines; improve mitochondrial function | Improve systemic inflammation, microvascular function, and metabolic balance; potential for lean-mass loss in sarcopenic patients | STEP-HFpEF and SUMMIT trials support HFpEF benefit; require monitoring of lean mass and body composition | [152,153,154,155,156,157,158] |

| FGF21 | Enhances mitochondrial repair; increases metabolic flexibility; reduces ER stress; regulates glucose and lipid metabolism | Counteracts metabolic inflexibility and lipotoxicity relevant to HFpEF and sarcopenia | Long-acting analogs show metabolic benefits; cardiac outcome trials ongoing | [55,56,57,58,59,60,161] |

| AdipoR Agonists | Activate AMPK/PPAR-α independently of adiponectin; promote mitochondrial biogenesis; improve endothelial NO | Overcome adiponectin resistance; reduce myocardial fibrosis; improve exercise capacity in preclinical HF models | Potential therapeutic class for metabolic–vascular restoration | [11,128,162,173] |

| Visceral and Epicardial Adipose Tissue Pathways | Secrete IL-6, TNF-α, resistin; suppress protective adipokines; induce microvascular inflammation | Promote coronary microvascular dysfunction and stiffening, central to HFpEF phenotype | GLP-1RAs selectively reduce these depots; possible imaging–biomarker integration | [22,24,41,82,83] |

| SOCS3/PTP1B Signaling | Negative regulators of leptin receptor JAK/STAT signaling | Induce leptin resistance and perpetuate hyperleptinemic inflammation | Pharmacologic inhibition restores leptin sensitivity in early research | [144,145,146,147] |

| Melanocortin-4 Receptor (MC4R) | Central regulator of energy balance and sympathetic tone; interacts with leptin–POMC axis | Activation confers cardioprotection despite peripheral leptin resistance | Setmelanotide demonstrates clinical feasibility of MC4R targeting | [129,149,151] |

| Inflammatory Adipokines (resistin, TNF-α, IL-6) | Activate NF-κB, JAK/STAT, MAPK pathways; promote oxidative stress | Contribute to myocardial fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction, and muscle catabolism | Modulated indirectly through weight-loss therapies and GLP-1RAs | [25,26,32,38] |

| Multimarker Scores (e.g., OROME) | Combine inflammatory and protective adipokines | Improve HFpEF risk stratification beyond natriuretic peptides | Incorporation into precision-medicine algorithms | [143] |

| Ectopic Fat + Adipokine Integration | Links regional fat depots to unique adipokine signatures | Explains phenotypic diversity in HFpEF | Supports machine-learning and multimodal biomarker platforms | [41,82,83,120,163] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Komić, L.; Komić, J.; Pavlović, N.; Kumrić, M.; Bukić, J.; Jerončić Tomić, I.; Božić, J. The Adipokine Axis in Heart Failure: Linking Obesity, Sarcopenia and Cardiac Dysfunction in HFpEF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020612

Komić L, Komić J, Pavlović N, Kumrić M, Bukić J, Jerončić Tomić I, Božić J. The Adipokine Axis in Heart Failure: Linking Obesity, Sarcopenia and Cardiac Dysfunction in HFpEF. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020612

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomić, Luka, Jelena Komić, Nikola Pavlović, Marko Kumrić, Josipa Bukić, Iris Jerončić Tomić, and Joško Božić. 2026. "The Adipokine Axis in Heart Failure: Linking Obesity, Sarcopenia and Cardiac Dysfunction in HFpEF" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020612

APA StyleKomić, L., Komić, J., Pavlović, N., Kumrić, M., Bukić, J., Jerončić Tomić, I., & Božić, J. (2026). The Adipokine Axis in Heart Failure: Linking Obesity, Sarcopenia and Cardiac Dysfunction in HFpEF. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020612