Asiatic Acid Attenuates Salmonella typhimurium-Induced Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Damage by Inhibiting the TLR2/Notch and NF-κB Pathway in Microglia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result

2.1. AA Reduces iNOS Expression to Suppress S.T-Induced Overproduction of NO in the Hippocampus

2.2. AA Inhibits S.T-Induced Activation of the NF-κB Pathway in the Hippocampus

2.3. AA Inhibits S.T-Induced Activation of the TLR2/Notch Pathway in the Hippocampus

2.4. S.T Infection Increase NO via iNOS in Microglia

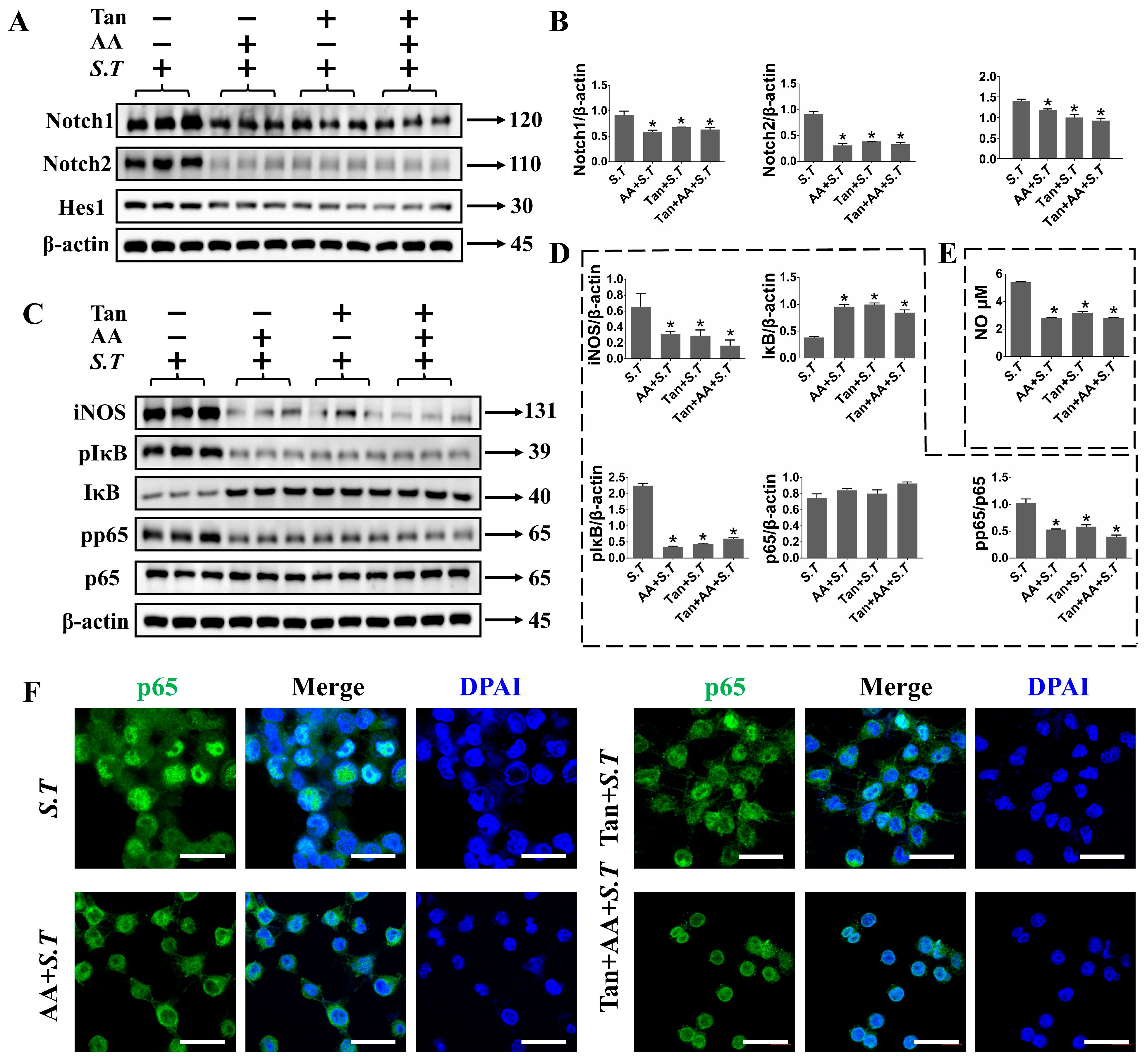

2.5. AA Inhibits S.T-Induced Activation of NF-κB Pathway in BV-2 Cells

2.6. AA Regulates TLR2/Notch Expression in S.T Stimulated BV-2 Cells

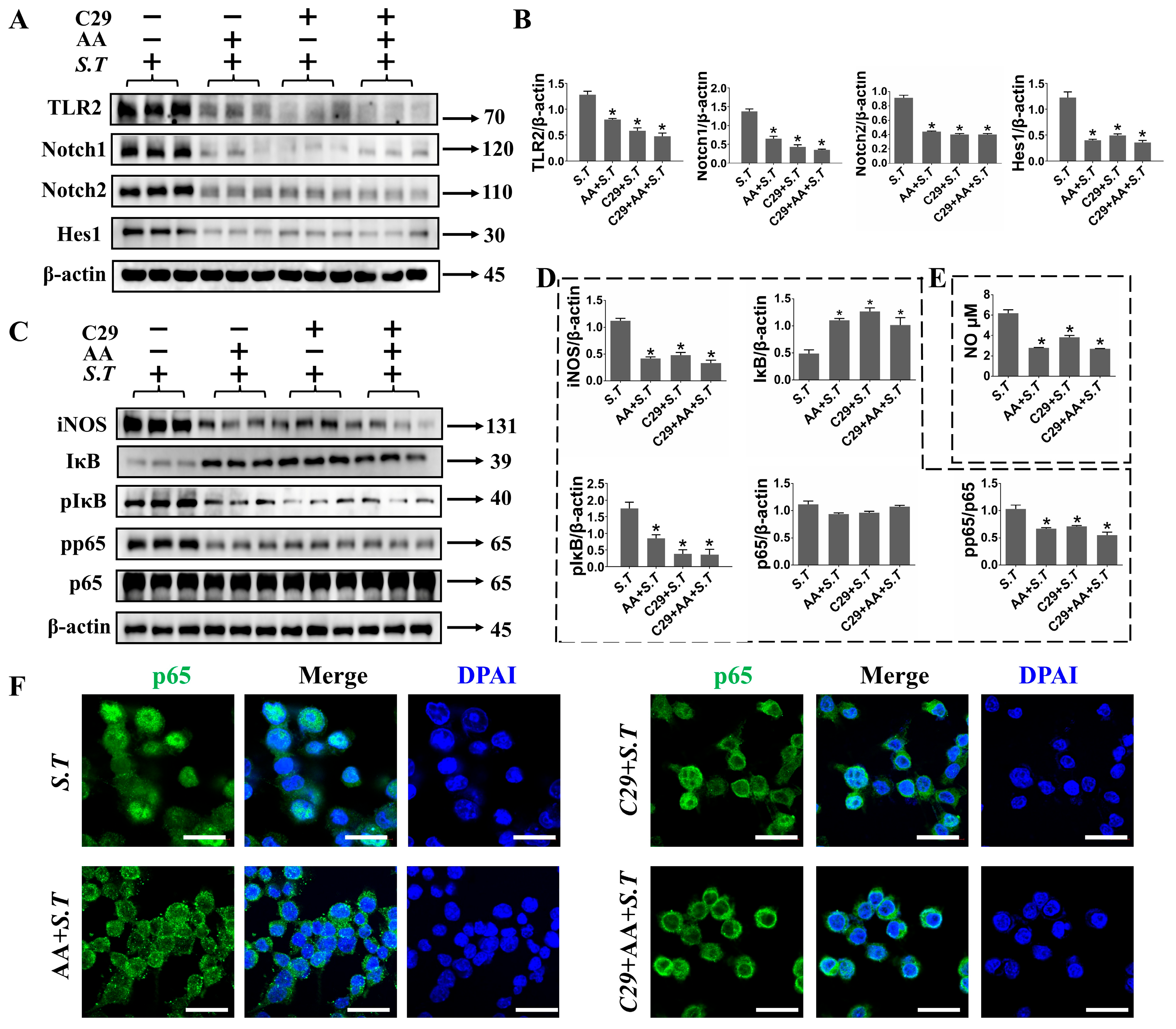

2.7. TLR2 Positively Regulates Notch Pathway in S.T Infection in BV-2 Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Antibodies

4.2. Animals

4.3. S.T and AA Act on BV-2 Cells

4.4. TEM

4.5. IHC

4.6. NO Assay

4.7. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.8. Immunoprecipitation (IP)

4.9. Western Blot

4.10. IF

4.11. CCK8

4.12. Mitochondrial Function Assay

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Salmonella Typhimurium Linked to Chocolate Products—Europe and the United States of America. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33736908 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Al-Yaqoobi, M.; Al-Khalili, S.; Mishra, G.P. Salmonella brain abscess in an infant. Neurosciences 2018, 23, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; Saito, E.K. Avian wildlife mortality events due to salmonellosis in the United States, 1985-2004. J. Wildlife Dis. 2008, 44, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sorge, N.M.; Zialcita, P.A.; Browne, S.H.; Quach, D.; Guiney, D.G.; Doran, K.S. Penetration and activation of brain endothelium by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsena, C.R.; Miller, A.S.; King, M.A. Salmonella Infections. Pediatr. Rev. 2019, 40, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, D.; Roy Chowdhury, A.; Biswas, B.; Chakravortty, D. Salmonella Typhimurium Infection Leads to Colonization of the Mouse Brain and Is Not Completely Cured with Antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Li, W.; Hou, X.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Yan, X.; Yang, B.; Huang, D.; Liu, B.; Feng, L. Nitric oxide is a host cue for Salmonella Typhimurium systemic infection in mice. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, M.; Joo, J.; Alvarado-Martinez, Z.; Tabashsum, Z.; Aditya, A.; Biswas, D. Intracellular autolytic whole cell Salmonella vaccine prevents colonization of pathogenic Salmonella Typhimurium in chicken. Vaccine 2022, 40, 6880–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.M.S.; Abdel-Azeem, N.M.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Helmy, N.A.; Radi, A.M. Neuromodulatory effect of cinnamon oil on behavioural disturbance, CYP1A1, iNOStranscripts and neurochemical alterations induced by deltamethrin in rat brain. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Song, N.; Cui, Y.; Chang, Y. Albicanol antagonizes Cd-induced apoptosis through a NO/iNOS-regulated mitochondrial pathway in chicken liver cells. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallorini, M.; Maccallini, C.; Ammazzalorso, A.; Amoia, P.; De Filippis, B.; Fantacuzzi, M.; Giampietro, L.; Cataldi, A.; Amoroso, R. The Selective Acetamidine-Based iNOS Inhibitor CM544 Reduces Glioma Cell Proliferation by Enhancing PARP-1 Cleavage In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Du, S.; Chen, T.; Chen, S.; et al. Excessive Activation of Notch Signaling in Macrophages Promote Kidney Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Necroptosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 835879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.S.; Yang, R.; Jiang, C.H.; Zhu, L.P.; Xu, Y.Y.; Pan, K.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Z.Q. Asiatic acid from Cyclocarya paliurus regulates the autophagy-lysosome system via directly inhibiting TGF-beta type I receptor and ameliorates diabetic nephropathy fibrosis. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 5536–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, D.C.; Walthert, S.; Locatelli, G. Central Nervous System Barriers Impact Distribution and Expression of iNOS and Arginase-1 in Infiltrating Macrophages During Neuroinflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 666961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pang, J.; Ye, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Lin, N.; Lee, T.H.; Liu, H. Disorders of the central nervous system: Insights from Notch and Nrf2 signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lina, T.T.; Dunphy, P.S.; Luo, T.; McBride, J.W. Ehrlichia chaffeensis TRP120 Activates Canonical Notch Signaling to Downregulate TLR2/4 Expression and Promote Intracellular Survival. mBio 2016, 7, e00672-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, A.M.; Alotaibi, H.N.; El-Orabi, N. Dibenzazepine, a gamma-Secretase Enzyme Inhibitor, Protects Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Suppressing NF-kappaB, iNOS, and Hes1/Hey1 Expression. Inflammation 2025, 48, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Ding, D.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Sun, Y.Y.; Wu, J. Lipoxin A4 regulates microglial M1/M2 polarization after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via the Notch signaling pathway. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 339, 113645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Xu, M.; Du, W.; Fang, Z.Q.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.J.; Song, P.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.W.; Yue, Z.S.; et al. Myeloid-specific blockade of Notch signaling ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 1941–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.Q.; Cai, G.L.; Liu, K.; Zhuang, Z.; Jia, K.P.; Pei, S.Y.; Wang, X.Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, S.N.; Cui, C.; et al. Microglia exosomal miRNA-137 attenuates ischemic brain injury through targeting Notch1. Aging 2021, 13, 4079–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Cheng, H.; Xu, L.; Pei, G.; Wang, Y.; Fu, C.; Jiang, Y.; He, C.; et al. Signaling pathways and targeted therapy for myocardial infarction. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mei, W.; Chen, J.; Jiang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Yin, G.; Fan, J. Gamma-secretase inhibitor suppressed Notch1 intracellular domain combination with p65 and resulted in the inhibition of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway induced by IL-1beta and TNF-alpha in nucleus pulposus cells. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 1903–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, A.; Shahzad, M.; Shabbir, A.; Shahid, H.; Shahid, K.; Javeed, A. Carica papaya ameliorates allergic asthma via down regulation of IL-4, IL-5, eotaxin, TNF-alpha, NF-kB, and iNOS levels. Phytomedicine 2017, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.R.L.; Calado, L.L.; Duarte, A.B.S.; de Sousa, D.P. Centella asiatica and Its Metabolite Asiatic Acid: Wound Healing Effects and Therapeutic Potential. Metabolites 2023, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varada, S.; Chamberlin, S.R.; Bui, L.; Brandes, M.S.; Gladen-Kolarsky, N.; Harris, C.J.; Hack, W.; Neff, C.J.; Brumbach, B.H.; Soumyanath, A.; et al. Oral Asiatic Acid Improves Cognitive Function and Modulates Antioxidant and Mitochondrial Pathways in Female 5xFAD Mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, C.; Thayumanavan, P. Asiatic acid prevents the quinolinic acid-induced oxidative stress and cognitive impairment. Metab. Brain Dis. 2018, 33, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Xin, Z.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, L.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Xin, H.B. Asiatic acid suppresses neuroinflammation in BV2 microglia via modulation of the Sirt1/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sun, J.; Cong, Q.J.; Chen, W.X.; Ahsan, H.M.; Gao, J.; Qian, J.J. Asiatic Acid Protects Dopaminergic Neurons from Neuroinflammation by Suppressing Mitochondrial Ros Production. Biomol. Ther. 2019, 27, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.Y.; Wan, W.C.; Li, Q.M.; Wan, W.W.; Long, Y.; Liu, H.Z.; Yang, X. Asiatic acid attenuates diabetic retinopathy through TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappa B p65 mediated modulation of microglia polarization. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.L.; Guo, P.; Liu, A.M.; Wu, Q.H.; Xue, X.J.; Dai, M.H.; Hao, H.H.; Qu, W.; Xie, S.Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Nitric oxide (NO)-mediated mitochondrial damage plays a critical role in T-2 toxin -induced apoptosis and growth hormone deficiency in rat anterior pituitary GH3 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 102, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, D.Y. Hippocampus and nitric oxide. Vitam. Horm. 2014, 96, 127–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.J.; Xu, B.; Huang, S.W.; Luo, X.; Deng, X.L.; Luo, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhou, L. Baicalin prevents LPS-induced activation of TLR4/NF-kappaB p65 pathway and inflammation in mice via inhibiting the expression of CD14. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.C.; Feng, B.; Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, P.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, A.K.; Li, H.L. Tollip is a critical mediator of cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J. Pathol. 2015, 237, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.S.; Pang, J.; Weir, A.; Kong, I.Y.; Fritsch, M.; Rashidi, M.; Cooney, J.P.; Davidson, K.C.; Speir, M.; Djajawi, T.M.; et al. Interferon-gamma primes macrophages for pathogen ligand-induced killing via a caspase-8 and mitochondrial cell death pathway. Immunity 2022, 55, 423–441.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bao, X.; Weng, X.; Bai, X.; Feng, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, S.; Jia, H.; Yu, B. The protective effect of quercetin on macrophage pyroptosis via TLR2/Myd88/NF-kappaB and ROS/AMPK pathway. Life Sci. 2022, 291, 120064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kang, H.; Baek, J.H.; Cho, M.G.; Chung, E.J.; Kim, S.J.; Chung, J.Y.; Chun, K.H. Disrupting Notch signaling related HES1 in myeloid cells reinvigorates antitumor T cell responses. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksoud, M.J.E.; Tellios, V.; Xiang, Y.Y.; Lu, W.Y. Nitric oxide displays a biphasic effect on calcium dynamics in microglia. Nitric Oxide 2021, 108, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.J.; McCorrister, S.; Grant, C.; Westmacott, G.; Fariss, R.; Hu, P.; Zhao, K.; Blake, M.; Whitmire, B.; Yang, C.; et al. Chlamydial Protease-Like Activity Factor and Type III Secreted Effectors Cooperate in Inhibition of p65 Nuclear Translocation. mBio 2016, 7, e01427-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Cruz, A.; de la Rosa, E.J.; Hernandez-Sanchez, C. TLR2 Is Highly Overexpressed in Retinal Myeloid Cells in the rd10 Mouse Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1415, 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Akbar, I.; Kumari, B.; Vrati, S.; Basu, A.; Banerjee, A. Japanese Encephalitis Virus-induced let-7a/b interacted with the NOTCH-TLR7 pathway in microglia and facilitated neuronal death via caspase activation. J. Neurochem. 2019, 149, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, D.M. Neuroimmunology and neuroinflammation in autoimmune, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disease. Immunology 2018, 154, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, J.R.; Poore, C.P.; Sulaimee, N.H.B.; Pareek, T.; Cheong, W.F.; Wenk, M.R.; Pant, H.C.; Frautschy, S.A.; Low, C.M.; Kesavapany, S. Curcumin Ameliorates Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Memory Deficits in p25 Transgenic Mouse Model that Bears Hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 60, 1429–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, A.; Wolf, T.; Sitzmann, A.; Willette, A.A. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Pleiotropic roles for cytokines and neuronal pentraxins. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 347, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.E.; Saini, D.K. The ERK-p38MAPK-STAT3 Signalling Axis Regulates iNOS Expression and Salmonella Infection in Senescent Cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 744013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Joseph, J.P.; Jagdish, S.; Chaudhuri, S.; Ramteke, N.S.; Karhale, A.K.; Waturuocha, U.; Saini, D.K.; Nandi, D. High throughput screening identifies auranofin and pentamidine as potent compounds that lower IFN-gamma-induced Nitric Oxide and inflammatory responses in mice: DSS-induced colitis and Salmonella Typhimurium-induced sepsis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Castroverde, C.D.M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Albaqami, M.; Aftab, T. Molecular Mechanisms of Nitric Oxide (NO) Signaling and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Homeostasis during Abiotic Stresses in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, R.; Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, M.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. Deficiency of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) enhances MC903-induced atopic dermatitis-like inflammation in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 771, 152028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, M.S.; Zaichick, S.V.; Mao, M.; de Abreu, A.L.; Bakhshi, F.R.; Hart, P.C.; Saqib, U.; Deng, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Block, M.L.; et al. NOS1-derived nitric oxide promotes NF-kappaB transcriptional activity through inhibition of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1725–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.N.; Venosa, A.; Gow, A.J. Cell Origin and iNOS Function Are Critical to Macrophage Activation Following Acute Lung Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 761496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, S.; Chausse, B.; Dikmen, H.O.; Almouhanna, F.; Hollnagel, J.O.; Lewen, A.; Kann, O. TLR2- and TLR3-activated microglia induce different levels of neuronal network dysfunction in a context-dependent manner. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 96, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jing, B.; Chen, Z.N.; Li, X.; Shi, H.M.; Zheng, Y.C.; Chang, S.Q.; Gao, L.; Zhao, G.P. Ferulic acid alleviates sciatica by inhibiting neuroinflammation and promoting nerve repair via the TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolini, G.P.; Lima, G.K.; Lucinda, N.; Silva, M.A.; Dias, M.F.; Pessoa, N.L.; Coura, B.P.; Cartelle, C.T.; Arantes, R.M.E.; Kroon, E.G.; et al. Defense against HSV-1 in a murine model is mediated by iNOS and orchestrated by the activation of TLR2 and TLR9 in trigeminal ganglia. J. Neuroinflamm. 2014, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, R.; Han, Q.; Zhang, C.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, J. Toll-Like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR9 play opposing roles in host innate immunity against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.H.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, J.W.; Choi, S.Y.; Choi, K.D.; Rhee, J.K.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Choi, J.H. Rare Variants of Putative Candidate Genes Associated with Sporadic Meniere’s Disease in East Asian Population. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.X.; Feng, X.; Xu, X.M.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Jia, S.Y.; Li, B.; Chen, W.; Wei, Y.D. Integrated Analysis Reveals Altered Lipid and Glucose Metabolism and Identifies NOTCH2 as a Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease Related Depression. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Zheng, K.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Shan, X. Interference of Notch1 inhibits the growth of glioma cancer cells by inducing cell autophagy and down-regulation of Notch1-Hes-1 signaling pathway. Med. Oncol. 2015, 32, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Fu, N.; Wang, S.; Zhao, R.C. Human adipose and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles mitigate photoaging via TIMP1/Notch1. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, W.; Pear, W.S. Notch and PI3K: How is the road traveled? Blood 2012, 120, 1349–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Y.Z.; Li, M.D.; Nie, C.X. Curcumin Promotes Proliferation of Adult Neural Stem Cells and the Birth of Neurons in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice via Notch Signaling Pathway. Cell. Reprogram. 2019, 21, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, F.; Soufi, F.G.; Ghiasi, R.; Khamaneh, A.M.; Alipour, M.R. Alteration in Inflammation-related miR-146a Expression in NF-KB Signaling Pathway in Diabetic Rat Hippocampus. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.S.; Yin, P.; Shi, Y.R.; Jin, N.; Gao, Q.; Li, J.D.; Liu, F.H. A Novel Biological Role of -Mangostin via TAK1-NF-B Pathway against Inflammatory. Inflammation 2019, 42, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-kappaB in biology and targeted therapy: New insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateba, S.B.; Mvondo, M.A.; Ngeu, S.T.; Tchoumtchoua, J.; Awounfack, C.F.; Njamen, D.; Krenn, L. Natural Terpenoids Against Female Breast Cancer: A 5-year Recent Research. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 3162–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, W.; Li, J. Asiatic Acid Attenuates Salmonella typhimurium-Induced Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Damage by Inhibiting the TLR2/Notch and NF-κB Pathway in Microglia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020602

Zou W, Li J. Asiatic Acid Attenuates Salmonella typhimurium-Induced Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Damage by Inhibiting the TLR2/Notch and NF-κB Pathway in Microglia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020602

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Wenshu, and Jianxi Li. 2026. "Asiatic Acid Attenuates Salmonella typhimurium-Induced Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Damage by Inhibiting the TLR2/Notch and NF-κB Pathway in Microglia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020602

APA StyleZou, W., & Li, J. (2026). Asiatic Acid Attenuates Salmonella typhimurium-Induced Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Damage by Inhibiting the TLR2/Notch and NF-κB Pathway in Microglia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020602