The Role of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) in Bone Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evidence of GIP Effects on Bone

2.1. In Vitro Studies

2.1.1. Effects of GIP on Osteoblast-Lineage Cells

2.1.2. Effects of GIP on Osteoclasts and Osteoclast Precursors

2.2. Effects of Endogenous GIP Signaling on Bone

2.2.1. Genetic GIP/GIPR Alterations and Bone Phenotype in Animals and Humans

2.2.2. GIPR Antagonist Studies

2.3. Effects of Exogenous GIP Signaling on Bone in Healthy Subjects

2.4. Effects of Exogenous GIP Signaling on Bone Under Pathological Conditions

2.4.1. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis

2.4.2. Inflammatory Bone Diseases

2.4.3. Obesity and Diabetes

2.4.4. Other Pathological Conditions

2.5. Effects of GIP Signaling on Orthodontic Tooth Movement

3. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| I.v. | Intravenous |

| GIP | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GIPR | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor |

| Gs | Stimulatory G protein |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

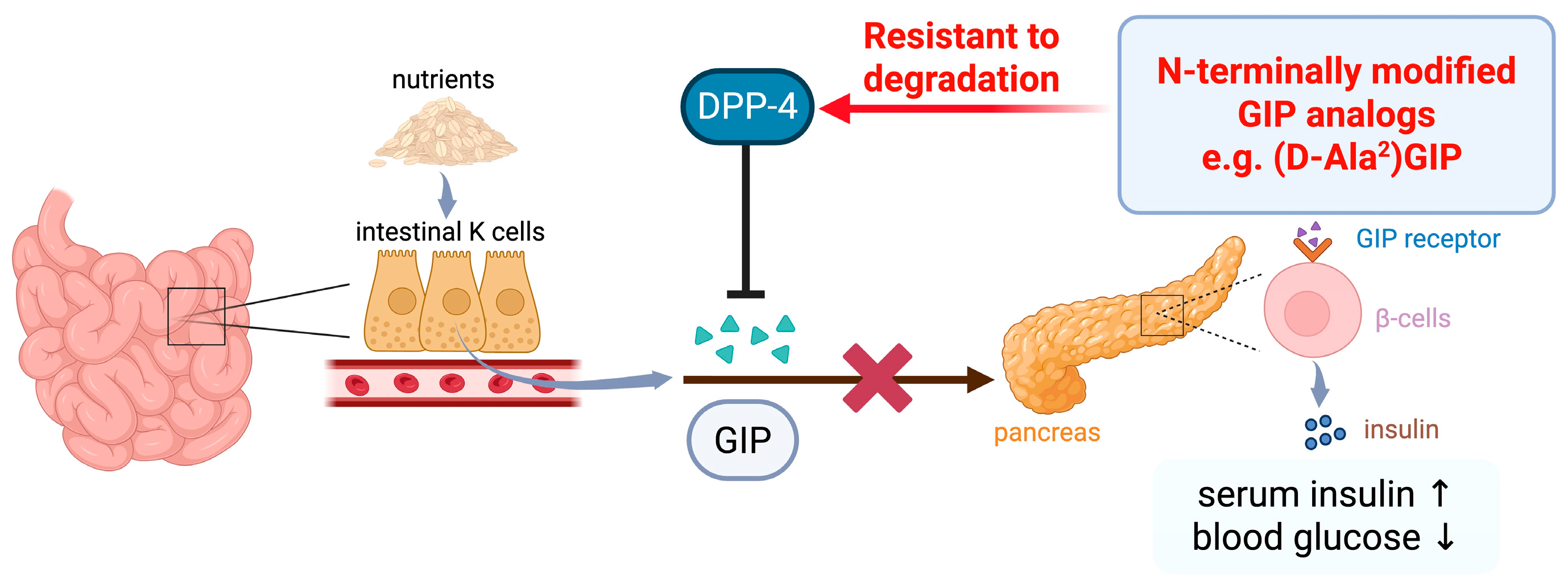

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

| GLP-1R | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor |

| GCGR | Glucagon receptor |

| GLP-2 | Glucagon-like peptide-2 |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| RANK | Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| P1NP | Procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide |

| LOX | Lysyl oxidase |

| PKA | Protein Kinase A |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| BMMs | Bone marrow macrophages |

| NFATc1 | Nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| PYD | Pyridinoline |

| GIPRKO | GIP receptor-deficient |

| BMC | Bone mineral content |

| CTX | C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen |

| OGTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| MMTs | Mixed meal tests |

| I.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| S.c. | Subcutaneous |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| OVX | Ovariectomy |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| GCF | Gingival crevicular fluid |

| TRAP | Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase |

| CTSK | Cathepsin K |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| T1DM | Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| IIGI | Isoglycemic intravenous glucose infusion |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| BV/TV | Bone volume fraction |

| Tb.N | Trabecular number |

| MAR | Mineral apposition rate |

| MS/BS | Mineralizing surface per bone surface |

| BFR/BS | Bone formation rate per bone surface |

| N.Oc/B.Pm | Number of osteoclasts per bone perimeter |

| Oc.S/BS | Osteoclast surface per bone surface |

| PI-CF | Pancreatic-insufficient cystic fibrosis |

| OTM | Orthodontic tooth movement |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| GLP-2R | Glucagon-like peptide-2 receptor |

References

- Müller, T.D.; Adriaenssens, A.; Ahrén, B.; Blüher, M.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Campbell, J.E.; Coghlan, M.P.; D’Alessio, D.; Deacon, C.F.; DelPrato, S.; et al. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP). Mol. Metab. 2025, 95, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Incretin Hormones: Their Role in Health and Disease. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Yabe, D. GIP and GLP-1, the Two Incretin Hormones: Similarities and Differences. J. Diabetes Investig. 2010, 1, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.M.; Boylan, M.O.; Chin, W.W. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide in Incretin Physiology: Role in Health and Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2025, 46, 479–500, Correction in Endocr. Rev. 2025, 46, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, D.; Seino, Y. Two Incretin Hormones GLP-1 and GIP: Comparison of Their Actions in Insulin Secretion and β Cell Preservation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011, 107, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, D.J.; Holst, J.J. The Expanding Incretin Universe: From Basic Biology to Clinical Translation. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1765–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, S.; Harada, N.; Inagaki, N. Physiology and Clinical Applications of GIP. Endocr. J. 2025, 72, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayendraraj, A.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Gasbjerg, L.S. GLP-1 and GIP Receptor Signaling in Beta Cells—A Review of Receptor Interactions and Co-Stimulation. Peptides 2022, 151, 170749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koefoed-Hansen, F.; Helsted, M.M.; Kizilkaya, H.S.; Lund, A.B.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Gasbjerg, L.S. The Evolution of the Therapeutic Concept ‘GIP Receptor Antagonism’. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1570603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørregaard, P.K.; Deryabina, M.A.; Tofteng Shelton, P.; Fog, J.U.; Daugaard, J.R.; Eriksson, P.-O.; Larsen, L.F.; Jessen, L. A Novel GIP Analogue, ZP4165, Enhances Glucagon-like Peptide-1-Induced Body Weight Loss and Improves Glycaemic Control in Rodents. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Harte, F.P.M.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A.; Conlon, J.M.; Flatt, P.R. Amino Terminal Glycation of Gastric Inhibitory Polypeptide Enhances Its Insulinotropic Action on Clonal Pancreatic B-Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1998, 1425, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, V.A.; O’Harte, F.P.M.; Harriott, P.; Flatt, P.R. Degradation, Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate Production, Insulin Secretion, and Glycemic Effects of Two Novel N-Terminal Ala2-Substituted Analogs of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide with Preserved Biological Activity In Vivo. Metabolism 2003, 52, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinke, S.A.; Gelling, R.W.; Pederson, R.A.; Manhart, S.; Nian, C.; Demuth, H.-U.; McIntosh, C.H.S. Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV-Resistant [d-Ala2]Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Improves Glucose Tolerance in Normal and Obese Diabetic Rats. Diabetes 2002, 51, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinke, S.A.; Manhart, S.; Kühn-Wache, K.; Nian, C.; Demuth, H.-U.; Pederson, R.A.; McIntosh, C.H.S. [Ser2]- and [Ser(P)2]Incretin Analogs: Comparison of Dipeptidyl Peptidase Iv Resistance and Biological Activities In Vitro and In Vivo*. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 3998–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.P.; Pratley, R.E. GLP-1 Analogs and DPP-4 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Therapy: Review of Head-to-Head Clinical Trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, D.J. The GLP-1 Journey: From Discovery Science to Therapeutic Impact. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e175634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, N.M.; Pathak, V.; Gault, V.A.; McClean, S.; Irwin, N.; Flatt, P.R. Novel Dual Incretin Agonist Peptide with Antidiabetic and Neuroprotective Potential. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 155, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, V.K.; Kerr, B.D.; Flatt, P.R.; Gault, V.A. A Novel GIP-Oxyntomodulin Hybrid Peptide Acting through GIP, Glucagon and GLP-1 Receptors Exhibits Weight Reducing and Anti-Diabetic Properties. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollag, R.J.; Zhong, Q.; Phillips, P.; Min, L.; Zhong, L.; Cameron, R.; Mulloy, A.L.; Rasmussen, H.; Qin, F.; Ding, K.H.; et al. Osteoblast-Derived Cells Express Functional Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide Receptors. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollag, R.J.; Zhong, Q.; Ding, K.H.; Phillips, P.; Zhong, L.; Qin, F.; Cranford, J.; Mulloy, A.L.; Cameron, R.; Isales, C.M. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide Is an Integrative Hormone with Osteotropic Effects. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2001, 177, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clowes, J.A.; Hannon, R.A.; Yap, T.S.; Hoyle, N.R.; Blumsohn, A.; Eastell, R. Effect of Feeding on Bone Turnover Markers and Its Impact on Biological Variability of Measurements. Bone 2002, 30, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnason, N.H.; Henriksen, E.E.G.; Alexandersen, P.; Christgau, S.; Henriksen, D.B.; Christiansen, C. Mechanism of Circadian Variation in Bone Resorption. Bone 2002, 30, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Mathiesen, D.S.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Esposito, K.; Lund, A.B.; Knop, F.K. The Effects of GIP, GLP-1 and GLP-2 on Markers of Bone Turnover: A Review of the Gut–Bone Axis. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 265, e240231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, A.; Christensen, M.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T.; Holst, J.J.; Hartmann, B. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Inhibits Bone Resorption in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2325–E2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, L.J.; Partridge, N.C. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Bone Remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25103–25108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teitelbaum, S.L. Bone Resorption by Osteoclasts. Science 2000, 289, 1504–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledesma-Colunga, M.G.; Passin, V.; Lademann, F.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Rauner, M. Novel Insights into Osteoclast Energy Metabolism. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2023, 21, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, W.J.; Simonet, W.S.; Lacey, D.L. Osteoclast Differentiation and Activation. Nature 2003, 423, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, T.; Hayashi, M.; Fukunaga, T.; Kurata, K.; Oh-hora, M.; Feng, J.Q.; Bonewald, L.F.; Kodama, T.; Wutz, A.; Wagner, E.F.; et al. Evidence for Osteocyte Regulation of Bone Homeostasis through RANKL Expression. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Onal, M.; Jilka, R.L.; Weinstein, R.S.; Manolagas, S.C.; O’Brien, C.A. Matrix-Embedded Cells Control Osteoclast Formation. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Piemontese, M.; Onal, M.; Campbell, J.; Goellner, J.J.; Dusevich, V.; Bonewald, L.; Manolagas, S.C.; O’Brien, C.A. Osteocytes, Not Osteoblasts or Lining Cells, Are the Main Source of the RANKL Required for Osteoclast Formation in Remodeling Bone. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, J.M.; Zheng, Y.; Dunstan, C.R. RANK Ligand. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2007, 39, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marahleh, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Mizoguchi, I. The Osteocyte and Its Osteoclastogenic Potential. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1121727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Takahashi, N.; Jimi, E.; Udagawa, N.; Takami, M.; Kotake, S.; Nakagawa, N.; Kinosaki, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shima, N.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor α Stimulates Osteoclast Differentiation by a Mechanism Independent of the ODF/RANKL–RANK Interaction. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, H.; Marahleh, A.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Nara, Y.; Pramusita, A.; Kinjo, R.; Ma, J.; Kanou, K.; Mizoguchi, I. Role of the Interaction of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors 1 and 2 in Bone-Related Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahara, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Kamei, K.; Alman, B.A. The Origins and Roles of Osteoclasts in Bone Development, Homeostasis and Repair. Development 2022, 149, dev199908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Itokawa, T.; Sridhar, S.; Ding, K.-H.; Xie, D.; Kang, B.; Bollag, W.B.; Bollag, R.J.; Hamrick, M.; Insogna, K.; et al. Effects of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide on Osteoclast Function. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, E543–E548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Shi, X.; Zhong, Q.; Kang, B.; Xie, D.; Bollag, W.B.; Bollag, R.J.; Hill, W.; Washington, W.; Mi, Q.; et al. Impact of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide on Age-Induced Bone Loss. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlier, J.L.; Kharroubi, I.; Zhang, J.; Dalla Valle, A.; Rigutto, S.; Mathieu, M.; Gangji, V.; Rasschaert, J. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide Prevents Serum Deprivation-Induced Apoptosis in Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Osteoblastic Cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2015, 11, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Pantoja, E.L.; Ranganath, L.R.; Gallagher, J.A.; Wilson, P.J.; Fraser, W.D. Receptors and Effects of Gut Hormones in Three Osteoblastic Cell Lines. BMC Physiol. 2011, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiyama, K.; Yamada, Y.; Yamada, C.; Harada, N.; Kawasaki, Y.; Ogura, M.; Bessho, K.; Li, M.; Amizuka, N.; Sato, M.; et al. Gastric Inhibitory Polypeptide as an Endogenous Factor Promoting New Bone Formation after Food Ingestion. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.S.; Søe, K.; Christensen, L.L.; Fernandez-Guerra, P.; Hansen, N.W.; Wyatt, R.A.; Martin, C.; Hardy, R.S.; Andersen, T.L.; Olesen, J.B.; et al. GIP Reduces Osteoclast Activity and Improves Osteoblast Survival in Primary Human Bone Cells. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 188, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowska, A.; Bouvard, B.; Chappard, D.; Mabilleau, G. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Directly Affects Collagen Fibril Diameter and Collagen Cross-Linking in Osteoblast Cultures. Bone 2015, 74, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyavahare, S.S.; Mieczkowska, A.; Flatt, P.R.; Chappard, D.; Irwin, N.; Mabilleau, G. GIP Analogues Augment Bone Strength by Modulating Bone Composition in Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Peptides 2020, 125, 170207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, E.J.; Pajevic, P.D.; Roy, S.; Trackman, P.C. Impaired Gastric Hormone Regulation of Osteoblasts and Lysyl Oxidase Drives Bone Disease in Diabetes Mellitus. JBMR Plus 2019, 3, e10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabilleau, G.; Perrot, R.; Mieczkowska, A.; Boni, S.; Flatt, P.R.; Irwin, N.; Chappard, D. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Dose-Dependently Reduces Osteoclast Differentiation and Resorption. Bone 2016, 91, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Marahleh, A.; Ma, J.; Ren, J.; Miura, M.; Fan, Z.; Narita, K.; et al. (D-Ala2)GIP Inhibits Inflammatory Bone Resorption by Suppressing TNF-α and RANKL Expression and Directly Impeding Osteoclast Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.L.; Wyatt, R.A.; Correia, J.; Areej, Z.; Hinds, M.; Crastin, A.; Hardy, R.S.; Frost, M.; Gorvin, C.M. Identification of Anti-Resorptive GPCRs by High-Content Imaging in Human Osteoclasts. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2025, 74, e240143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Zhong, Q.; Ding, K.-H.; Cheng, H.; Williams, S.; Correa, D.; Bollag, W.B.; Bollag, R.J.; Insogna, K.; Troiano, N.; et al. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Peptide-Overexpressing Transgenic Mice Have Increased Bone Mass. Bone 2007, 40, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobron, B.; Bouvard, B.; Vyavahare, S.; Blom, L.V.; Pedersen, K.K.; Windeløv, J.A.; Boer, G.A.; Harada, N.; Zhang, S.; Shimazu-Kuwahara, S.; et al. Enteroendocrine K Cells Exert Complementary Effects to Control Bone Quality and Mass in Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Cheng, H.; Hamrick, M.; Zhong, Q.; Ding, K.-H.; Correa, D.; Williams, S.; Mulloy, A.; Bollag, W.; Bollag, R.J.; et al. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Receptor Knockout Mice Have Altered Bone Turnover. Bone 2005, 37, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudin-Audrain, C.; Irwin, N.; Mansur, S.; Flatt, P.R.; Thorens, B.; Baslé, M.; Chappard, D.; Mabilleau, G. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Receptor Deficiency Leads to Modifications of Trabecular Bone Volume and Quality in Mice. Bone 2013, 53, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowska, A.; Irwin, N.; Flatt, P.R.; Chappard, D.; Mabilleau, G. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Receptor Deletion Leads to Reduced Bone Strength and Quality. Bone 2013, 56, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, J.-P.; Schroeder, J.C.; Zhu, Y.; Beinborn, M.; Kopin, A.S. Pharmacological Characterization of Human Incretin Receptor Missense Variants. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 332, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torekov, S.S.; Harsløf, T.; Rejnmark, L.; Eiken, P.; Jensen, J.B.; Herman, A.P.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Holst, J.J.; Langdahl, B.L. A Functional Amino Acid Substitution in the Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Receptor (GIPR) Gene Is Associated With Lower Bone Mineral Density and Increased Fracture Risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E729–E733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabe, M.B.N.; van der Velden, W.J.C.; Gadgaard, S.; Smit, F.X.; Hartmann, B.; Bräuner-Osborne, H.; Rosenkilde, M.M. Enhanced Agonist Residence Time, Internalization Rate and Signalling of the GIP Receptor Variant [E354Q] Facilitate Receptor Desensitization and Long-Term Impairment of the GIP System. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 126, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilkaya, H.S.; Sørensen, K.V.; Kibsgaard, C.J.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Hauser, A.S.; Sparre-Ulrich, A.H.; Grarup, N.; Rosenkilde, M.M. Loss of Function Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Receptor Variants Are Associated With Alterations in BMI, Bone Strength and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 749607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, G.; McGuigan, F.E.; Kumar, J.; Luthman, H.; Lyssenko, V.; Akesson, K. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) and GIP Receptor (GIPR) Genes: An Association Analysis of Polymorphisms and Bone in Young and Elderly Women. Bone Rep. 2016, 4, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; He, J.; Sun, X.; Pang, D.; Hu, J.; Feng, B. GIPR Rs10423928 and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women in Shanghai. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styrkarsdottir, U.; Tragante, V.; Stefansdottir, L.; Thorleifsson, G.; Oddsson, A.; Sørensen, E.; Erikstrup, C.; Schwarz, P.; Jørgensen, H.L.; Lauritzen, J.B.; et al. Obesity Variants in the GIPR Gene Are Not Associated With Risk of Fracture or Bone Mineral Density. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e1608–e1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbjerg, L.S.; Christensen, M.B.; Hartmann, B.; Lanng, A.R.; Sparre-Ulrich, A.H.; Gabe, M.B.N.; Dela, F.; Vilsbøll, T.; Holst, J.J.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; et al. GIP(3-30)NH2 Is an Efficacious GIP Receptor Antagonist in Humans: A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmar, M.; Asmar, A.; Simonsen, L.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Sparre-Ulrich, A.H.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Hartmann, B.; Dela, F.; Holst, J.J.; Bülow, J. The Gluco- and Liporegulatory and Vasodilatory Effects of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Are Abolished by an Antagonist of the Human GIP Receptor. Diabetes 2017, 66, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasbjerg, L.S.; Bari, E.J.; Stensen, S.; Hoe, B.; Lanng, A.R.; Mathiesen, D.S.; Christensen, M.B.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; et al. Dose-Dependent Efficacy of the Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Receptor Antagonist GIP(3-30)NH2 on GIP Actions in Humans. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbjerg, L.S.; Hartmann, B.; Christensen, M.B.; Lanng, A.R.; Vilsbøll, T.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Holst, J.J.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Knop, F.K. GIP’s Effect on Bone Metabolism Is Reduced by the Selective GIP Receptor Antagonist GIP(3–30)NH2. Bone 2020, 130, 115079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsted, M.M.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Lanng, A.R.; Bergmann, N.C.; Stensen, S.; Hartmann, B.; Christensen, M.B.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsbøll, T.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; et al. The Role of Endogenous GIP and GLP-1 in Postprandial Bone Homeostasis. Bone 2020, 140, 115553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, L.S.L.; Helsted, M.M.; Englund, A.; Bergmann, N.C.; Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Nielsen, C.K.; Hansen, C.P.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; et al. Acute Effects of GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Antagonism in Totally Pancreatectomized Individuals: A Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 28, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensen, S.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Krogh, L.L.; Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Sparre-Ulrich, A.H.; Jensen, M.H.; Dela, F.; Hartmann, B.; Vilsbøll, T.; Holst, J.J.; et al. Effects of Endogenous GIP in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 185, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassano, S.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Kizilkaya, H.S.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Holst, J.J.; Hartmann, B. Increased Body Weight and Fat Mass After Subchronic GIP Receptor Antagonist, but Not GLP-2 Receptor Antagonist, Administration in Rats. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabilleau, G.; Mieczkowska, A.; Irwin, N.; Simon, Y.; Audran, M.; Flatt, P.R.; Chappard, D. Beneficial Effects of a N-Terminally Modified GIP Agonist on Tissue-Level Bone Material Properties. Bone 2014, 63, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordrup, E.K.; Gadgaard, S.; Windeløv, J.; Holst, J.J.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Hartmann, B.; Rosenkilde, M.M. Development of a Long-Acting Unbiased GIP Receptor Agonist for Studies of GIP’s Role in Bone Metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 236, 116893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, D.B.; Alexandersen, P.; Bjarnason, N.H.; Vilsbøll, T.; Hartmann, B.; Henriksen, E.E.; Byrjalsen, I.; Krarup, T.; Holst, J.J.; Christiansen, C. Role of Gastrointestinal Hormones in Postprandial Reduction of Bone Resorption. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2003, 18, 2180–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Svane, M.S.; Martinussen, C.; Gabe, M.B.N.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Veedfald, S.; Bojsen-Møller, K.N.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; et al. GLP-2 and GIP Exert Separate Effects on Bone Turnover: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study in Healthy Young Men. Bone 2019, 125, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachner, T.D.; Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the Future. Lancet 2011, 377, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; McDonald, J.M. Disorders of Bone Remodeling. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011, 6, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabilleau, G.; Gobron, B.; Mieczkowska, A.; Perrot, R.; Chappard, D. Efficacy of Targeting Bone-Specific GIP Receptor in Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 239, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Veedfald, S.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Hartmann, B. Subcutaneous GIP and GLP-2 Inhibit Nightly Bone Resorption in Postmenopausal Women: A Preliminary Study. Bone 2021, 152, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, K.; Smolen, J.S. Inflammatory Bone Loss: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Intervention. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, A.L.; Abd El-Aleem, S.; Morales-Aza, B.; Donaldson, L.F. A Model of Periodontitis in the Rat: Effect of Lipopolysaccharide on Bone Resorption, Osteoclast Activity, and Local Peptidergic Innervation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2004, 31, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hienz, S.A.; Paliwal, S.; Ivanovski, S. Mechanisms of Bone Resorption in Periodontitis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 615486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Matsuguchi, T.; Tsuboi, N.; Mitani, A.; Tanaka, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Yamamoto, G.; Hishikawa, T.; Noguchi, T.; Yoshikai, Y. Gene Expression of Osteoclast Differentiation Factor Is Induced by Lipopolysaccharide in Mouse Osteoblasts Via Toll-Like Receptors. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 3574–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Lin, S.; Kok, S.; Cheng, S.; Lee, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, C.; Lin, L.; Wang, J. The Role of Lipopolysaccharide in Infectious Bone Resorption of Periapical Lesion. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2004, 33, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Hassan, F.; Tumurkhuu, G.; Dagvadorj, J.; Koide, N.; Naiki, Y.; Mori, I.; Yoshida, T.; Yokochi, T. Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Induces Osteoclast Formation in RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 360, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.G.; Idris, S.B.; Mustafa, M.; Ahmed, M.F.; Åstrøm, A.N.; Mustafa, K.; Ibrahim, S.O. Impact of Chronic Periodontitis on Levels of Glucoregulatory Biomarkers in Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Adults with and without Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solini, A.; Suvan, J.; Santini, E.; Gennai, S.; Seghieri, M.; Masi, S.; Petrini, M.; D’Aiuto, F.; Graziani, F. Periodontitis Affects Glucoregulatory Hormones in Severely Obese Individuals. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejera-Segura, B.; López-Mejías, R.; Domínguez-Luis, M.J.; de Vera-González, A.M.; González-Delgado, A.; Ubilla, B.; Olmos, J.M.; Hernández, J.L.; González-Gay, M.A.; Ferraz-Amaro, I. Incretins in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Miyajima, S.; Adachi, K.; Mizutani, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Miyazawa, K.; Goto, S.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Role of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide in Periodontitis. J. Diabetes Investig. 2016, 7, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Hussain, M.E. Obesity and Diabetes: An Update. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2017, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234, Correction in Lancet 2025, 405, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hygum, K.; Starup-Linde, J.; Langdahl, B.L. Diabetes and Bone. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2019, 5, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why Does Obesity Cause Diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, N.; Chandran, M.; Pierroz, D.D.; Abrahamsen, B.; Schwartz, A.V.; Ferrari, S.L.; On behalf of the IOF Bone and Diabetes Working Group. Mechanisms of Diabetes Mellitus-Induced Bone Fragility. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, H.; Ogawa, S.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Marahleh, A.; Nara, Y.; Pramusita, A.; Kinjo, R.; Ma, J.; Kanou, K.; et al. Effects of Incretin-Related Diabetes Drugs on Bone Formation and Bone Resorption. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinonapoli, G.; Pace, V.; Ruggiero, C.; Ceccarini, P.; Bisaccia, M.; Meccariello, L.; Caraffa, A. Obesity and Bone: A Complex Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkastaris, K.; Goulis, D.G.; Potoupnis, M.; Anastasilakis, A.D.; Kapetanos, G. Obesity, Osteoporosis and Bone Metabolism. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2020, 20, 372–381. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, N.C.; Lund, A.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Jessen, L.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; Christensen, M.B.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K. Separate and Combined Effects of GIP and GLP-1 Infusions on Bone Metabolism in Overweight Men Without Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 2953–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, S.A.; Mieczkowska, A.; Bouvard, B.; Flatt, P.R.; Chappard, D.; Irwin, N.; Mabilleau, G. Stable Incretin Mimetics Counter Rapid Deterioration of Bone Quality in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 3009–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, M.B.; Lund, A.; Calanna, S.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Inhibits Bone Resorption Independently of Insulin and Glycemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbürger, S.M.N.; Hoe, B.; Nielsen, C.N.; Bergman, N.C.; Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; Dela, F.; Overgaard, J.; Størling, J.; et al. GIP Affects Hepatic Fat and Brown Adipose Tissue Thermogenesis but Not White Adipose Tissue Transcriptome in Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 3261–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Christiansen, C.B.; Hansen, L.S.; Windeløv, J.A.; Hedbäck, N.; Gasbjerg, L.S.; Hindsø, M.; Svane, M.S.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; et al. Effects of Exogenous GIP and GLP-2 on Bone Turnover in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, M.B.; Lund, A.B.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Reduces Bone Resorption in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvaa097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.V.; Mathiesen, D.S.; Christensen, M.B.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Helsted, M.M.; Bagger, J.I.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K.; Lund, A.B. The Separate and Combined Effects of GIP, GLP-1, and GLP-2 on Markers of Bone Turnover in Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov-Jeppesen, K.; Hepp, N.; Oeke, J.; Hansen, M.S.; Jafari, A.; Svane, M.S.; Balenga, N.; Olson, J.A., Jr.; Frost, M.; Kassem, M.; et al. The Antiresorptive Effect of GIP, But Not GLP-2, Is Preserved in Patients with Hypoparathyroidism—A Randomized Crossover Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.S.; Chen, X.; Zhao, L.; Daley, T.; Phillips, B.; Rickels, M.R.; Kelly, A.; Kindler, J.M. Effect of GIP and GLP-1 Infusion on Bone Resorption in Glucose Intolerant, Pancreatic Insufficient Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2025, 40, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.H.; Teixeira, H.; Tsai, A. Mechanistic Insight into Orthodontic Tooth Movement Based on Animal Studies: A Critical Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10., 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltha, J.C.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. Mechanobiology of Orthodontic Tooth Movement: An Update. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2023, 12, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahleh, A.; Ohori, F.; Ma, J.; Fan, Z.; Lin, A.; Narita, K.; Murakami, K.; Kitaura, H. Recent Advances in the Role of Osteocytes in Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, Y.; Kitaura, H.; Marahleh, A.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Pramusita, A.; Kinjo, R.; Ma, J.; Kanou, K.; Mizoguchi, I. Enhancement of Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Root Resorption in Ovariectomized Mice. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Kitaura, H.; Noguchi, T.; Ohori, F.; Marahleh, A.; Ma, J.; Ren, J.; Lin, A.; Narita, K.; Mizoguchi, I. Exacerbating Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Mice with Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. J. Dent. Sci. 2025, 20, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjo, R.; Kitaura, H.; Ogawa, S.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Marahleh, A.; Nara, Y.; Pramusita, A.; Ma, J.; Kanou, K.; et al. Micro-Osteoperforations Induce TNF-α Expression and Accelerate Orthodontic Tooth Movement via TNF-α-Responsive Stromal Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Marahleh, A.; Ma, J.; Lin, A.; Fan, Z.; Narita, K.; Murakami, K.; Kanetaka, H. The Role of Cytokines in Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu, M.; Shibata, Y.; Kitaura, H.; Chang, X.; Moriishi, T.; Hashimoto, F.; Yoshida, N.; Yamaguchi, A. Experimental Model of Tooth Movement by Orthodontic Force in Mice and Its Application to Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Deficient Mice. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2005, 24, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaura, H.; Yoshimatsu, M.; Fujimura, Y.; Eguchi, T.; Kohara, H.; Yamaguchi, A.; Yoshida, N. An Anti-c-Fms Antibody Inhibits Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanou, K.; Kitaura, H.; Noguchi, T.; Ohori, F.; Marahleh, A.; Kinjo, R.; Ma, J.; Ren, J.; Ogasawara, K.; Mizoguchi, I. Effect of Age on Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Mice. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marahleh, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Nara, Y.; Pramusita, A.; Kinjo, R.; Ma, J.; Kanou, K.; Mizoguchi, I. Effect of TNF-α on Osteocyte RANKL Expression during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohori, F.; Kitaura, H.; Marahleh, A.; Kishikawa, A.; Ogawa, S.; Qi, J.; Shen, W.-R.; Noguchi, T.; Nara, Y.; Mizoguchi, I. Effect of TNF-α-Induced Sclerostin on Osteocytes during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 9716758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohori, F.; Kitaura, H.; Marahleh, A.; Ma, J.; Miura, M.; Ren, J.; Narita, K.; Fan, Z.; Lin, A.; Mizoguchi, I. Osteocyte Necroptosis Drives Osteoclastogenesis and Alveolar Bone Resorption during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Kitaura, H.; Shen, W.-R.; Ogawa, S.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Marahleh, A.; Nara, Y.; Adya, P.; Mizoguchi, I. Effect of a DPP-4 Inhibitor on Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Associated Root Resorption. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7189084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.-R.; Kitaura, H.; Qi, J.; Ogawa, S.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Marahleh, A.; Nara, Y.; Adya, P.; Mizoguchi, I. Local Administration of High-Dose Diabetes Medicine Exendin-4 Inhibits Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Mice. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Miyabe, M.; Nakamura, N.; Ito, M.; Sekiya, T.; Kanada, S.; Hoshino, R.; Matsubara, T.; Miyazawa, K.; Goto, S.; et al. Impacts of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide on Orthodontic Tooth Movement-Induced Bone Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobron, B.; Couchot, M.; Irwin, N.; Legrand, E.; Bouvard, B.; Mabilleau, G. Development of a First-in-Class Unimolecular Dual GIP/GLP-2 Analogue, GL-0001, for the Treatment of Bone Fragility. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2023, 38, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, S.A.; Mieczkowska, A.; Flatt, P.R.; Bouvard, B.; Chappard, D.; Irwin, N.; Mabilleau, G. A New Stable GIP–Oxyntomodulin Hybrid Peptide Improved Bone Strength Both at the Organ and Tissue Levels in Genetically-Inherited Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Bone 2016, 87, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Ajabiya, J.; Teli, D.; Bojarska, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Tirzepatide, a New Era of Dual-Targeted Treatment for Diabetes and Obesity: A Mini-Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff Ania, M.; le Roux Carel, W.; Stefanski, A.; Aronne Louis, J.; Halpern, B.; Wharton, S.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Perreault, L.; Zhang, S.; Battula, R.; et al. Tirzepatide for Obesity Treatment and Diabetes Prevention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.; Cai, X.; Lin, C.; Yang, W.; Ji, L. Effects of Semaglutide and Tirzepatide on Bone Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhang, M.; Shi, B.; Luo, X.; Huang, R.; Luo, Z.; He, J.; Xue, S.; Li, N.; Ling, Z.; et al. Tirzepatide, a Dual GLP-1 and GIP Receptor Agonist, Promotes Bone Loss in Obese Mice via Gut Microbial-Related Metabolites. J. Orthop. Translat. 2025, 55, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.-H.; Liang, Y.-C.; Chan, K.-C.; Chou, Y.-H.; Wu, H.-T.; Ou, H.-Y. Association of Tirzepatide Use with Risk of Osteoporosis Compared with Other GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Retrospective Cohort Study Using the TriNetX Database. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 230, 112995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccou, J.; Gagnon, C.; Yu, E.W.; Rosen, C.J. Effects of Weight-Loss Interventions on Bone Health in People Living with Obesity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2025, 40, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GIPR Knockout Strategies | Reference | Skeletal Phenotypes | Proposed Explanations for Discrepancies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exons 4–5 deletion | [41,51] | Biomechanical properties ↓ Trabecular bone volume ↓ Bone formation ↓ Osteoclast number ↑ | Lesser extent of GIPR deletion; Adipokine profile difference—leptin ↑ |

| Exons 1–6 deletion | [52] | Biomechanical properties ↓ Trabecular bone volume ↑ Bone formation ↑ Osteoclast number ↓ | Greater extent of GIPR deletion—GLP-1 signaling compensation; Adipokine profile difference—adiponectin ↑ & leptin ↓ |

| Pathological Model | Treatment Dose | Administration | Duration | Bone Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVX rats | GIP 0.05 mg/kg | i.v. | 6 weeks | Vertebral BMD ↑ | [20] |

| OVX mice | N-AcGIP 25 nmol/kg | s.c. | Not reported | Osteoclast formation ↓ Bone resorption ↓ Biomechanical properties ↑ Modified trabecular microarchitecture | [46] |

| OVX mice | (D-Ala2)-GIP1-30 25 nmol/kg | i.p. | 8 weeks | Bone resorption ↓ Bone strength ↑ Modified cortical microarchitecture; | [75] |

| (D-Ala2)-GIP-Tag 25 nmol/kg | Bone resorption ↓ | ||||

| LPS-induced bone inflammation | (D-Ala2)GIP 25 nmol/kg | s.c. | 5 days | Osteoclast formation ↓ Bone resorption ↓ | [47] |

| Diet-induced obesity | (D-Ala2)GIP 25 nmol/kg | i.p. | 6 weeks | Bone strength ↑ No effects on bone microarchitecture | [44] |

| (D-Ala2)-GIP-Tag 25 nmol/kg | |||||

| STZ-induced T1DM mice | (D-Ala2)GIP 25 nmol/kg | i.p. | 3 weeks | Tissue-level bone strength ↑ Restored bone remodeling No effects on cortical microarchitecture | [96] |

| Pathological Model | Treatment Dose (GIP) | Administration | Duration | Bone Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postmenopausal women | 100 μg | s.c. | Single bolus | CTX ↓ P1NP ↑ | [76] |

| Overweight/ Obesity | 4 pmol/kg/min IIGI | i.v. | 4 h | CTX ↓ P1NP ↔ | [95] |

| T1DM | 4 pmol/kg/min Low/high glycemic clamp | i.v. | 90 min | CTX ↓ P1NP ↑ (transient, low glycemia) | [97] |

| 6 pmol/kg/min | s.c. | 6 days | CTX ↓ (3 h) P1NP ↔ | [98] | |

| T2DM | 200 μg | s.c. | Single bolus | CTX ↓ P1NP ↑ | [99] |

| 4 → 2 pmol/kg/min varied glycemic conditions | i.v. | 15 → 75 min | CTX ↓ P1NP ↑ (transient, hypoglycemia) | [100] | |

| 4 → 2 pmol/kg/min IIGI | i.v. | 20 → 30 min | CTX ↓ P1NP ↔ | [101] | |

| Hypoparathyroidism | 100 μg | s.c. | Single bolus | CTX ↓ P1NP ↔ | [102] |

| PI-CF | 4 pmol/kg/min | i.v. | 80 min | CTX ↓ | [103] |

| Context | Endogenous GIP (Genetic/Antagonist Studies) | Exogenous GIP (GIP/GIP Analog Studies) |

|---|---|---|

| Health | Postprandial bone resorption ↓ Maintaining skeletal homeostasis | Bone resorption ↓; formation ± ↑ Cortical bone properties ↑ |

| Postmenopausal osteoporosis (OVX/postmenopausal women) | — | Bone resorption ↓; formation ↑ Bone strength/microarchitecture ↑ |

| Inflammation | Potential protective effect | Bone resorption ↓ |

| T1DM | — | Restored bone remodeling Tissue-level bone strength ↑ |

| T2DM | Postprandial bone resorption ↓ | Bone resorption ↓; formation ± ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Marahleh, A.; Ma, J.; Fan, Z.; Narita, K.; Murakami, K.; Kanetaka, H. The Role of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) in Bone Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020600

Lin A, Kitaura H, Ohori F, Marahleh A, Ma J, Fan Z, Narita K, Murakami K, Kanetaka H. The Role of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) in Bone Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020600

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Angyi, Hideki Kitaura, Fumitoshi Ohori, Aseel Marahleh, Jinghan Ma, Ziqiu Fan, Kohei Narita, Kou Murakami, and Hiroyasu Kanetaka. 2026. "The Role of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) in Bone Metabolism" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020600

APA StyleLin, A., Kitaura, H., Ohori, F., Marahleh, A., Ma, J., Fan, Z., Narita, K., Murakami, K., & Kanetaka, H. (2026). The Role of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) in Bone Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020600