Assessment of Anxiety- and Depression-like Behaviors and Local Field Potential Changes in a Cryogenic Lesion Model of Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

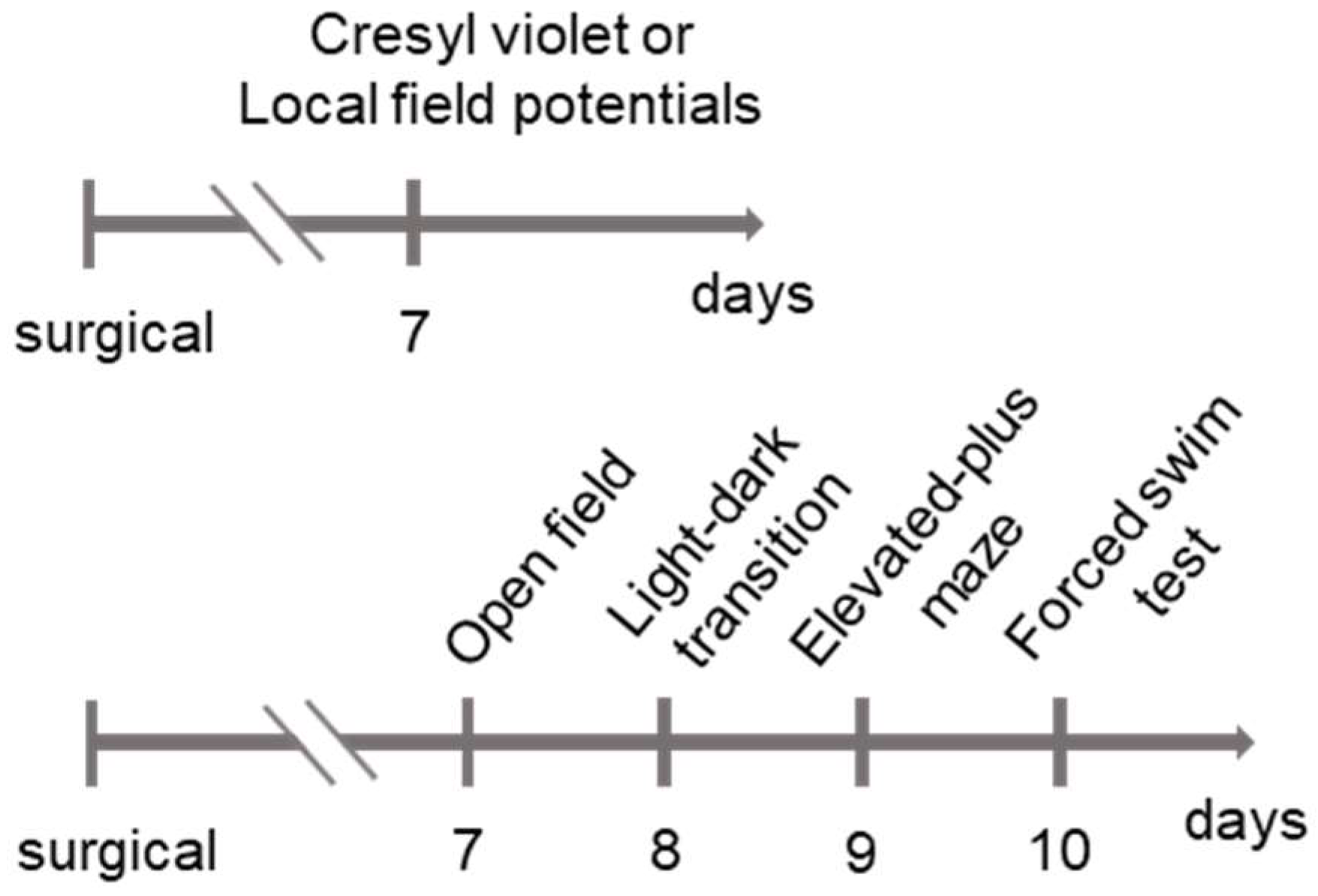

2.1. Reduction in Residual Cortical Size Following TBI

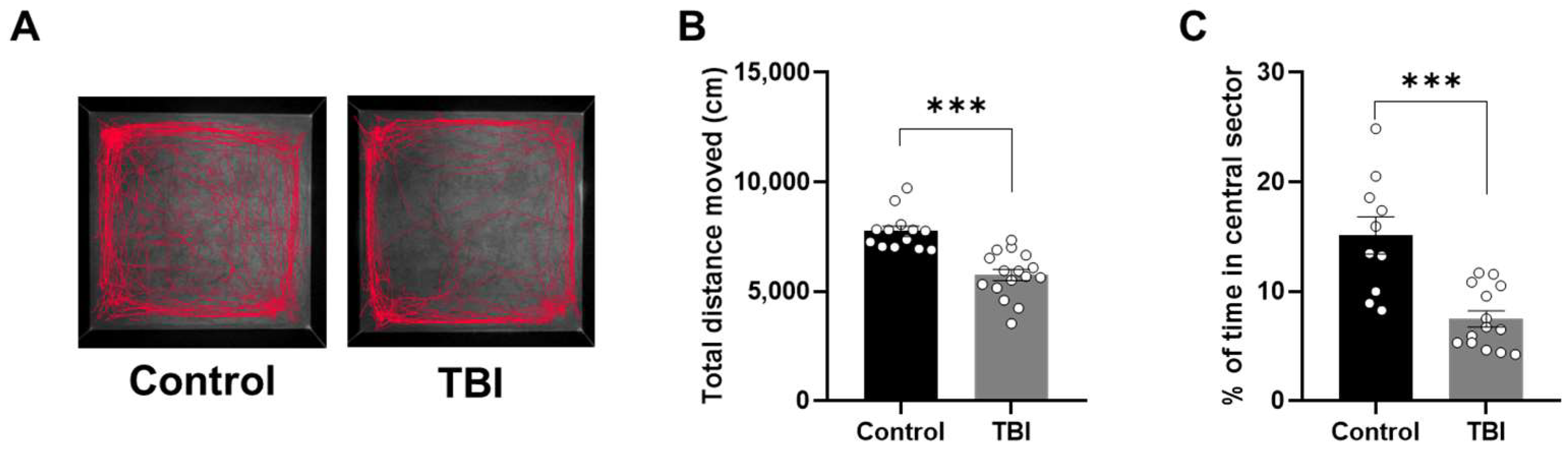

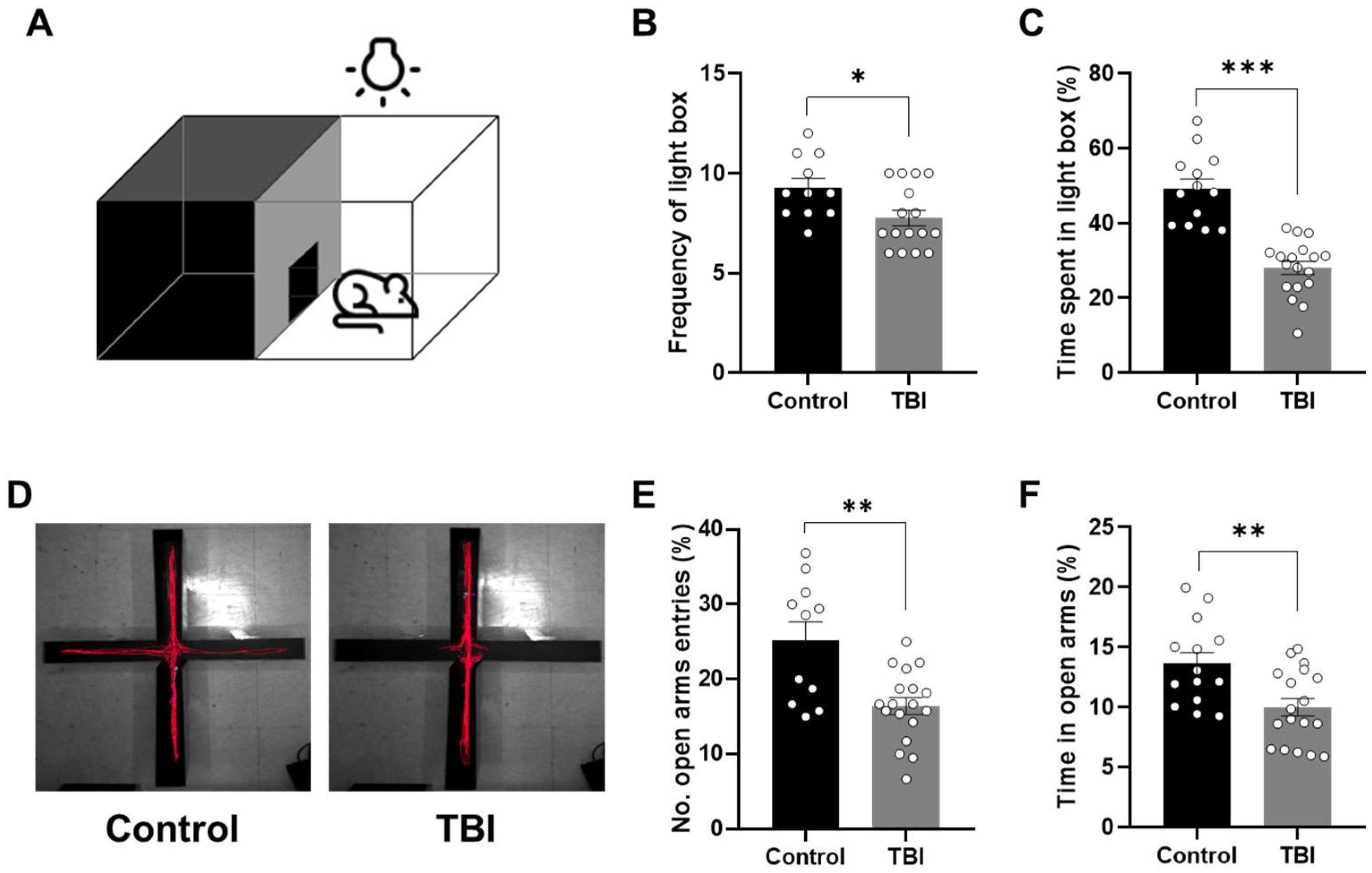

2.2. Decreased Locomotor Activity and Increased Anxiety-Related Behaviors Following TBI

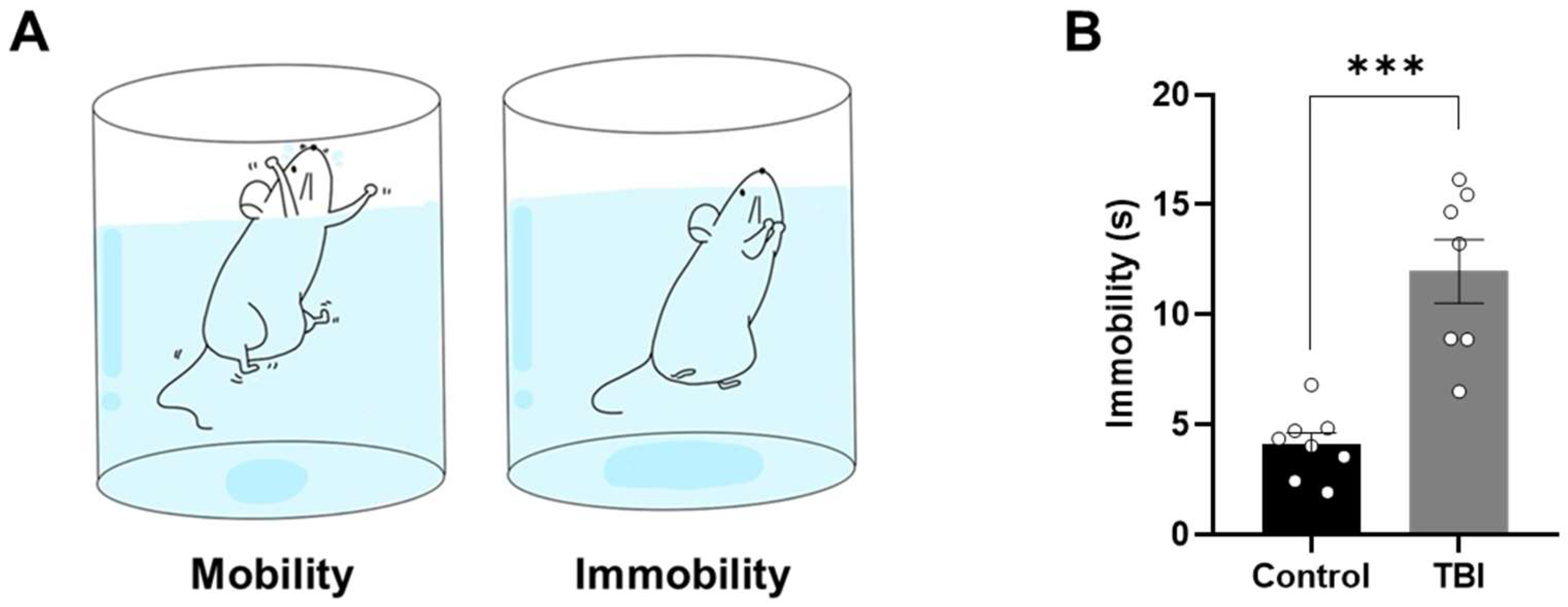

2.3. Increased Levels of Depression-Related Behaviors Following TBI

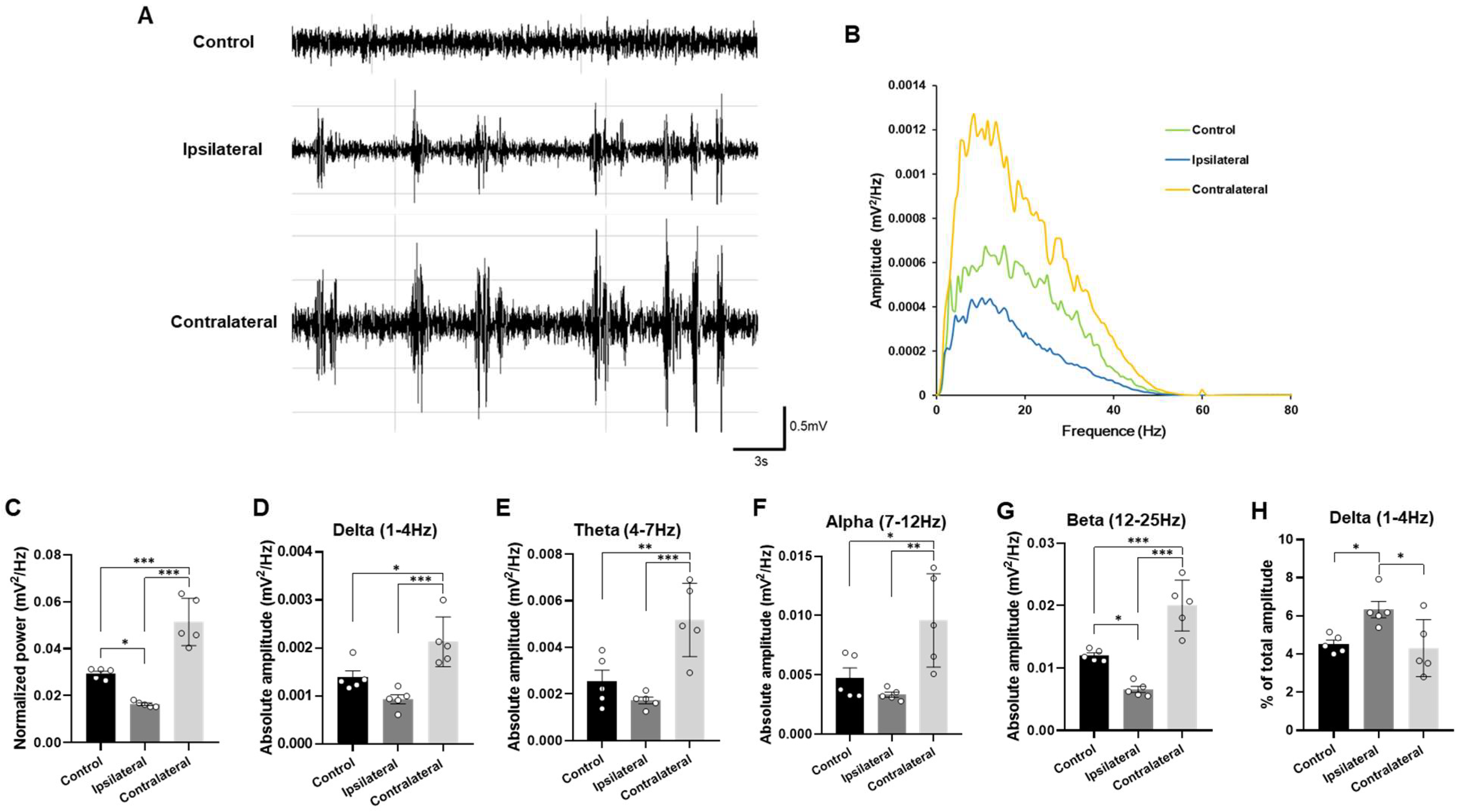

2.4. Representative Profiles of LFP After TBI

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

4.2. TBI Induction

4.3. Behavioral Tests

4.3.1. Open-Field Test

4.3.2. Light–Dark Transition Test

4.3.3. Elevated-Plus Maze Test

4.3.4. Forced Swim Test

4.4. Local Field Potentials (LFPs)

4.5. Tissue Processing and Cresyl Violet (CV) Staining

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mira, R.G.; Lira, M.; Cerpa, W. Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanisms of Glial Response. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 740939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobue, C.; Munro, C.; Schaffert, J.; Didehbani, N.; Hart, J.; Batjer, H.; Cullum, C.M. Traumatic Brain Injury and Risk of Long-Term Brain Changes, Accumulation of Pathological Markers, and Developing Dementia: A Review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 70, 629–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, F.; Compagnone, C.; Korsic, M.; Servadei, F.; Kraus, J. A Systematic Review of Brain Injury Epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochir. 2006, 148, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, N.H.; Tweedie, D.; Rachmany, L.; Li, Y.; Rubovitch, V.; Schreiber, S.; Chiang, Y.H.; Hoffer, B.J.; Miller, J.; Lahiri, D.K.; et al. Incretin Mimetics as Pharmacologic Tools to Elucidate and as a New Drug Strategy to Treat Traumatic Brain Injury. Alzheimers Dement. 2014, 10, S62–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhu, R.; Zhu, L.; Qiu, T.; Cao, Z.; Kang, T. Potassium Channels: Structures, Diseases, and Modulators. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2014, 83, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashman, T.A.; Gordon, W.A.; Cantor, J.B.; Hibbard, M.R. Neurobehavioral Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2006, 73, 999–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.H.; Kim, S.W.; Im, H.; Song, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, G.W.; Hwang, C.; Park, D.K.; Kim, D.S. Febrile Seizures Cause Depression and Anxiogenic Behaviors in Rats. Cells 2022, 11, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddenberg, T.E.; Komorowski, M.; Ruocco, L.A.; Silva, M.A.d.S.; Topic, B. Attenuating Effects of Testosterone on Depressive-like Behavior in the Forced Swim Test in Healthy Male Rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2009, 79, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmadhikari, A.S.; Tandle, A.L.; Jaiswal, S.V.; Sawant, V.A.; Vahia, V.N.; Jog, N. Frontal Theta Asymmetry as a Biomarker of Depression. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2018, 28, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gennaro, G.; Quarato, P.P.; Onorati, P.; Colazza, G.B.; Mari, F.; Grammaldo, L.G.; Ciccarelli, O.; Meldolesi, N.G.; Sebastiano, F.; Manfredi, M.; et al. Localizing Significance of Temporal Intermittent Rhythmic Delta Activity (TIRDA) in Drug-Resistant Focal Epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 70–78, Erratum in Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelisse, P.; Serafini, A.; Velizarova, R.; Genton, P.; Crespel, A. Temporal Intermittent Delta Activity: A Marker of Juvenile Absence Epilepsy? Seizure 2011, 20, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyko, M.; Gruenbaum, B.F.; Shelef, I.; Zvenigorodsky, V.; Severynovska, O.; Binyamin, Y.; Knyazer, B.; Frenkel, A.; Frank, D.; Zlotnik, A. Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Submissive Behavior in Rats: Link to Depression and Anxiety. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Gireesh, G.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Watanabe, M.; Shin, H.S. Phospholipase C Β4 in the Medial Septum Controls Cholinergic Theta Oscillations and Anxiety Behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 15375–15378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeller, A.A.; Duzzioni, M.; Duarte, F.S.; Leme, L.R.; Costa, A.P.R.; Santos, E.C.D.S.; De Pieri, C.H.; Dos Santos, A.A.; Naime, A.A.; Farina, M.; et al. GABA-A Receptor Modulators Alter Emotionality and Hippocampal Theta Rhythm in an Animal Model of Long-Lasting Anxiety. Brain Res. 2013, 1532, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Topiwala, M.A.; Gordon, J.A. Synchronized Activity between the Ventral Hippocampus and the Medial Prefrontal Cortex during Anxiety. Neuron 2010, 65, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Topiwala, M.A.; Gordon, J.A. Single Units in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex with Anxiety-Related Firing Patterns Are Preferentially Influenced by Ventral Hippocampal Activity. Neuron 2011, 71, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, B.R.; Salvadore, G.; Colon-Rosario, V.; Latov, D.R.; Holroyd, T.; Carver, F.W.; Coppola, R.; Manji, H.K.; Zarate, C.A.; Grillon, C. Abnormal Hippocampal Functioning and Impaired Spatial Navigation in Depressed Individuals: Evidence from Whole-Head Magnetoencephalography. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.F.; Kan, D.P.X.; Croarkin, P.; Phang, C.K.; Doruk, D. Neurophysiological Correlates of Depressive Symptoms in Young Adults: A Quantitative EEG Study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 47, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, D.K.; Song, H.Y.; Kim, D.S.; Gil, H.W. Altered Emotional Phenotypes in Chronic Kidney Disease Following 5/6 Nephrectomy. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, W.; Tang, H.; Wang, T.; Chen, Z.; Yao, Z.; Lu, Q. Alpha-Beta Decoupling Relevant to Inhibition Deficits Leads to Suicide Attempt in Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 314, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemoto, A.; Panier, L.Y.X.; Cole, S.L.; Kayser, J.; Pizzagalli, D.A.; Auerbach, R.P. Resting Posterior Alpha Power and Adolescent Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 141, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, P.J. Frontal Alpha Asymmetry and Its Modulation by Monoaminergic Neurotransmitters in Depression. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2024, 22, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, H.; Hua, L.; Dai, Z.; Wang, X.; Tang, H.; Han, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zou, H.; et al. Spontaneous Beta Power, Motor-Related Beta Power and Cortical Thickness in Major Depressive Disorder with Psychomotor Disturbance. NeuroImage Clin. 2023, 38, 103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.L.; Dai, Z.P.; Ridwan, M.C.; Lin, P.H.; Zhou, H.L.; Wang, H.F.; Yao, Z.J.; Lu, Q. Connectivity of the Frontal Cortical Oscillatory Dynamics Underlying Inhibitory Control During a Go/No-Go Task as a Predictive Biomarker in Major Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Choi, Y. Depression Diagnosis Based on Electroencephalography Power Ratios. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raslan, F.; Albert-Weißenberger, C.; Ernestus, R.I.; Kleinschnitz, C.; Sirén, A.L. Focal Brain Trauma in the Cryogenic Lesion Model in Mice. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2012, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.J.; Lifshitz, J.; Marklund, N.; Grady, M.S.; Graham, D.I.; Hovda, D.A.; Mcintosh, T.K. Lateral Fluid Percussion Brain Injury: A 15-Year Review and Evaluation. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 42–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert-Weissenberger, C.; Sirén, A.L. Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2010, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirén, A.L.; Radyushkin, K.; Boretius, S.; Kämmer, D.; Riechers, C.C.; Natt, O.; Sargin, D.; Watanabe, T.; Sperling, S.; Michaelis, T.; et al. Global Brain Atrophy after Unilateral Parietal Lesion and Its Prevention by Erythropoietin. Brain 2006, 129, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.H.; Kang, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Yoo, D.Y.; Park, D.K.; Kim, D.S. Altered Immunohistochemical Distribution of Hippocampal Interneurons Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Environ. Biol. 2019, 40, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.H.; Ramkumar, A.; Madanagopal, T.T.; Waly, M.I.; Tageldin, M.; Al-Abri, S.; Fahim, M.; Yasin, J.; Nemmar, A. Motor and Behavioral Changes in Mice with Cisplatin-Induced Acute Renal Failure. Physiol. Res. 2014, 63, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, C.E.; Mackay, C.E.; Lonie, J.A.; Bastin, M.E.; Terrière, E.; O’Carroll, R.E.; Ebmeier, K.P. MRI Correlates of Episodic Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Healthy Aging. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2010, 184, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josephs, K.A.; Murray, M.E.; Tosakulwong, N.; Whitwell, J.L.; Knopman, D.S.; Machulda, M.M.; Weigand, S.D.; Boeve, B.F.; Kantarci, K.; Petrucelli, L.; et al. Tau Aggregation Influences Cognition and Hippocampal Atrophy in the Absence of Beta-Amyloid: A Clinico-Imaging-Pathological Study of Primary Age-Related Tauopathy (PART). Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, M. Brain Consequences of Acute Kidney Injury: Focusing on the Hippocampus. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 37, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer-Teixeira, R.; Belchior, H.; Leão, R.N.; Ribeiro, S.; Tort, A.B.L. On High-Frequency Field Oscillations (>100 Hz) and the Spectral Leakage of Spiking Activity. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 1535–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuggetta, G.; Bennett, M.A.; Duke, P.A.; Young, A.M.J. Quantitative Electroencephalography as a Biomarker for Proneness Toward Developing Psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 153, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.H.; Lee, Y.R.; Park, D.-K.; Song, B.; Kim, D.-S. Assessment of Anxiety- and Depression-like Behaviors and Local Field Potential Changes in a Cryogenic Lesion Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020597

Yu YH, Lee YR, Park D-K, Song B, Kim D-S. Assessment of Anxiety- and Depression-like Behaviors and Local Field Potential Changes in a Cryogenic Lesion Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020597

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yeon Hee, Yu Ran Lee, Dae-Kyoon Park, Beomjong Song, and Duk-Soo Kim. 2026. "Assessment of Anxiety- and Depression-like Behaviors and Local Field Potential Changes in a Cryogenic Lesion Model of Traumatic Brain Injury" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020597

APA StyleYu, Y. H., Lee, Y. R., Park, D.-K., Song, B., & Kim, D.-S. (2026). Assessment of Anxiety- and Depression-like Behaviors and Local Field Potential Changes in a Cryogenic Lesion Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020597