Citrus limon Peel Extract Modulates Redox Enzymes and Induces Cytotoxicity in Human Gastric Cancer Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of Polyphenols Extracted from Lemon Peel Extract (LPE)

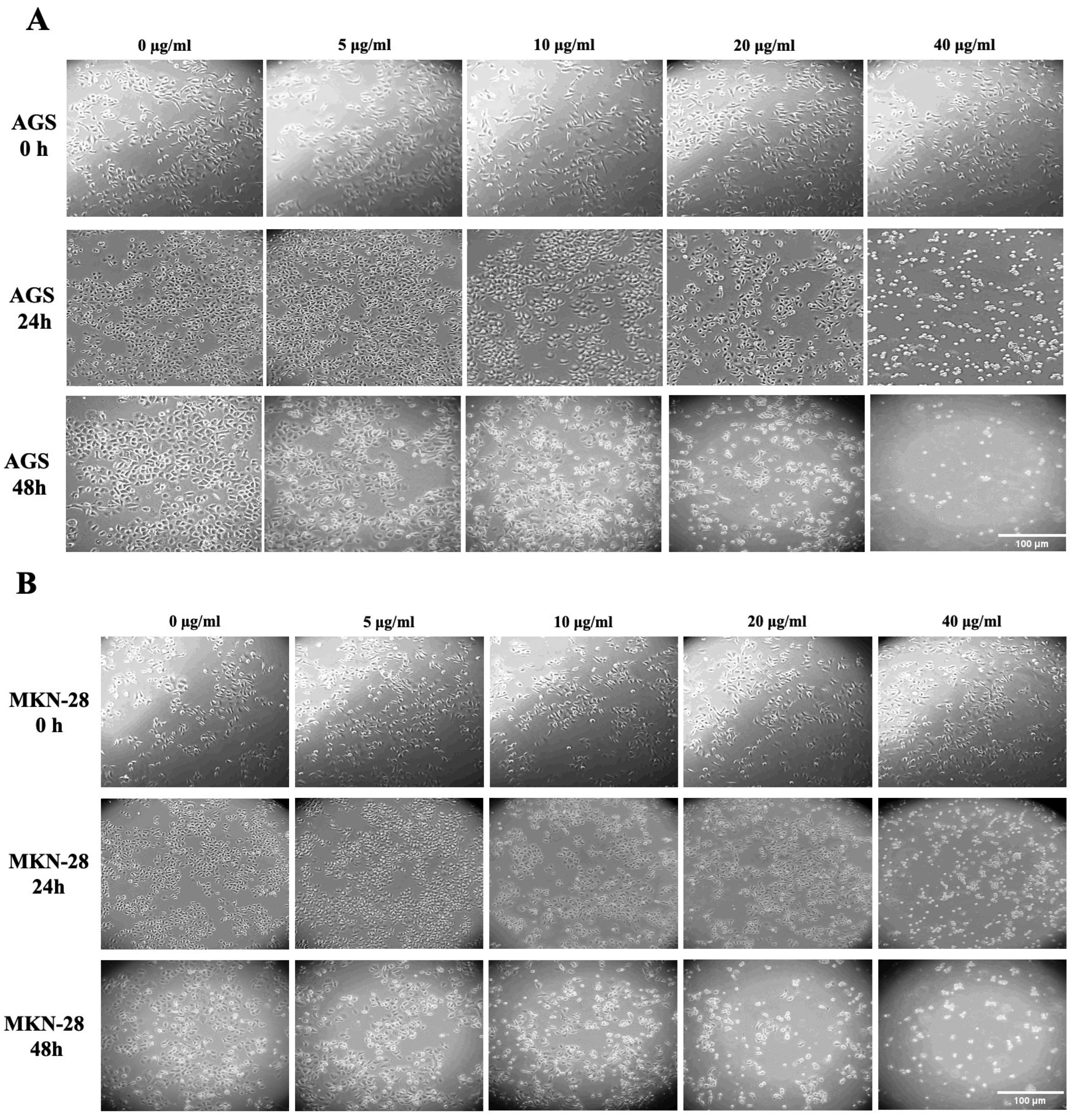

2.2. Effect of LPE on the Morphology of AGS and MKN-28 Gastric Adenocarcinoma Cells

2.3. Effect of LPE on Cell Viability of AGS and MKN-28 Cells

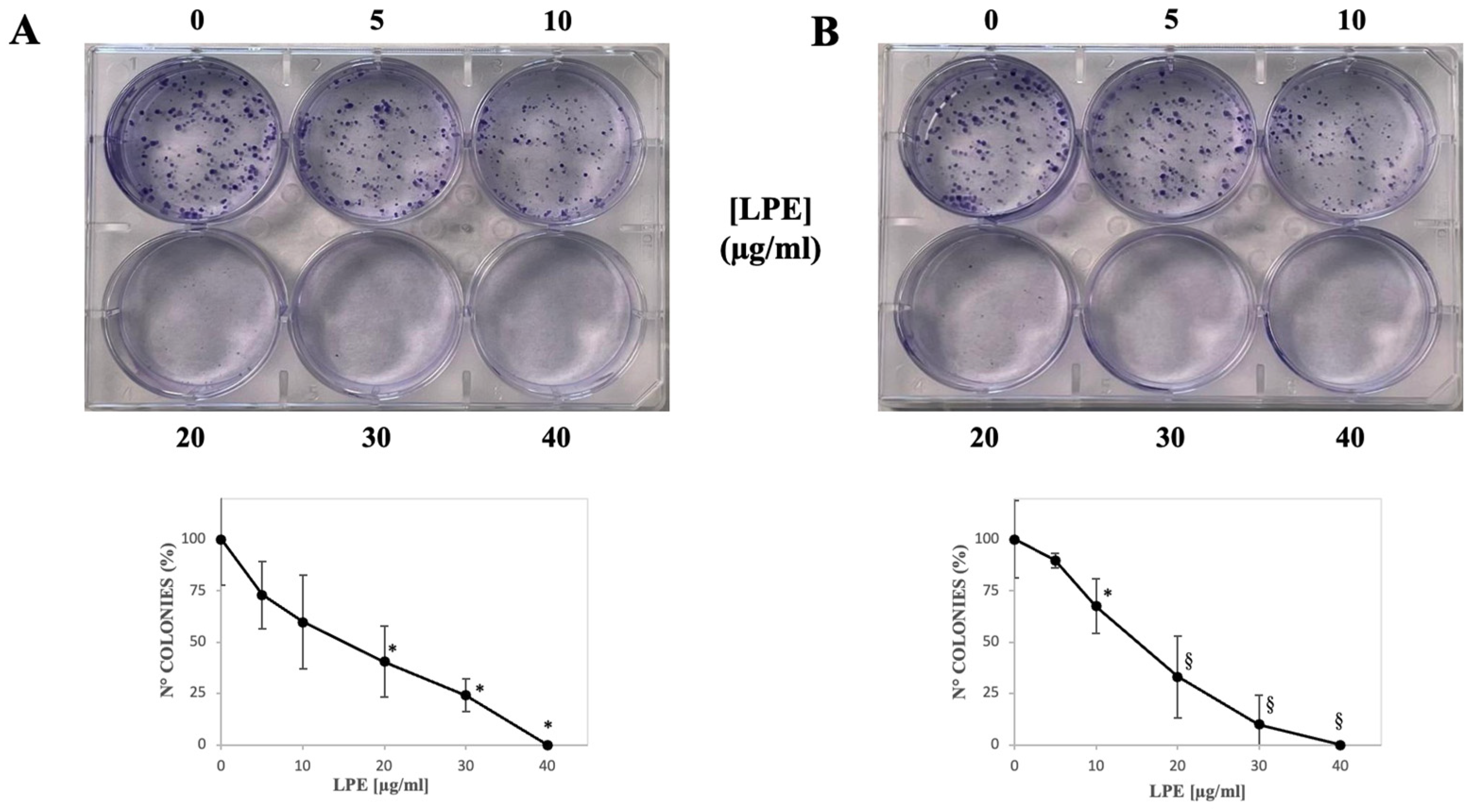

2.4. Effect of LPE on the Colony Formation Capability of AGS and MKN-28 Cells

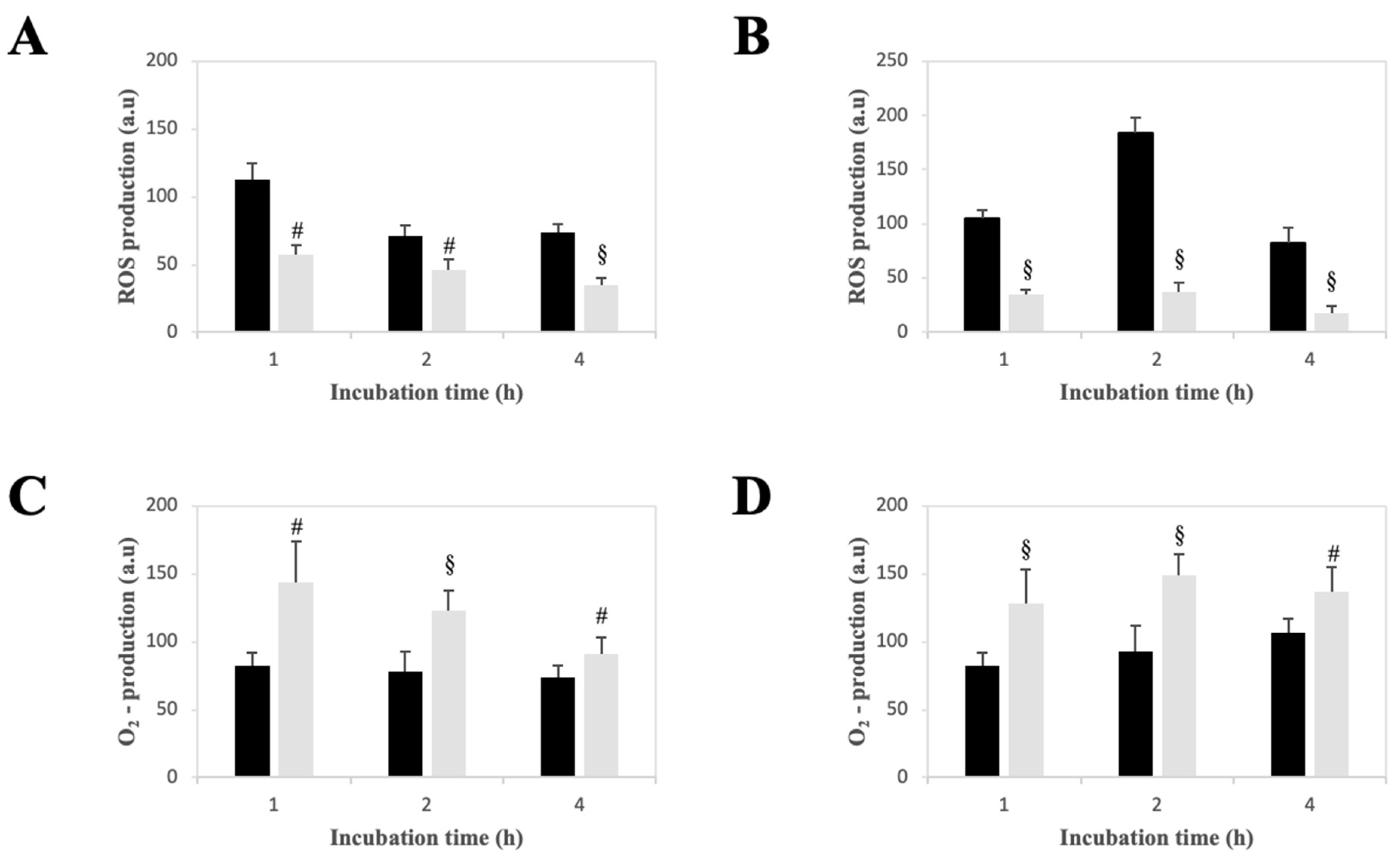

2.5. Effect of LPE on the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in AGS and MKN-28 Cells

2.6. Effect of LPE on the Protein Expression Levels of SOD-1, SOD-2, CAT, and MAO-A in AGS and MKN-28 Cells

2.7. Effect of LPE on SOD Activity in AGS and MKN-28 Cells

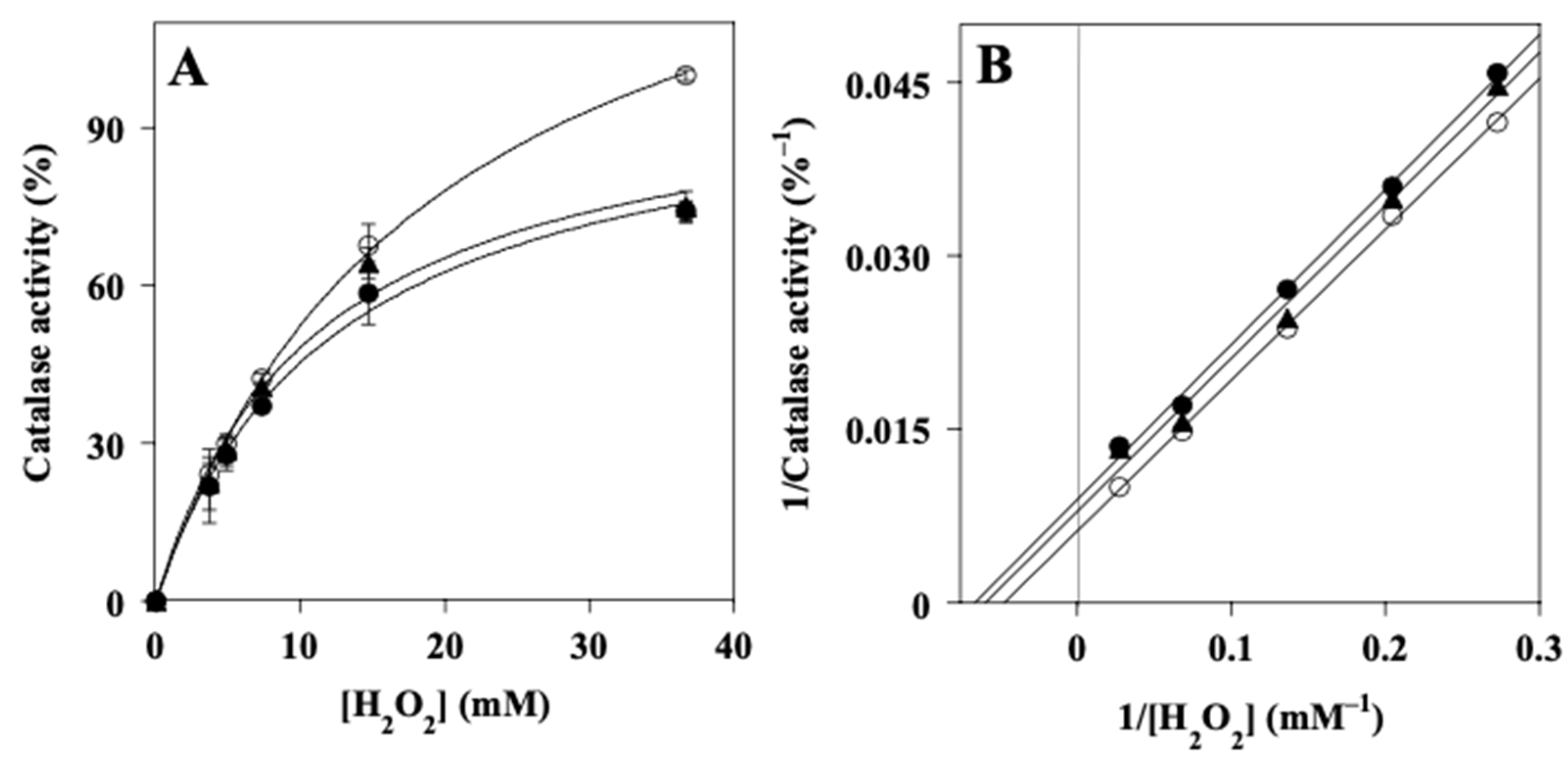

2.8. Effect of LPE on the Activity of Catalase (CAT)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Preparation of Lemon Peel Extract (LPE)

4.2.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Acids Content

4.2.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids

4.2.4. Cell Cultures

4.2.5. Morphological Analysis

4.2.6. Cell Viability Assay

4.2.7. Colony Formation Assay

4.2.8. Measurement of Intracellular ROS Content

4.2.9. Total Cell Lysates for Western Blotting Analysis

4.2.10. SOD Activity Assay

4.2.11. Biochemical Methods

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.J.; Zhao, H.P.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, L.; Liu, J.Y.; Pu, J.; Lv, J. Updates on global epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors of gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 2452–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlowska, J.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, M.; Maciejewski, R.; Sitarz, R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, E.; Tsilidis, K.K.; Triggi, M.; Siargkas, A.; Chourdakis, M.; Haidich, A.-B. Diet and Risk of Gastric Cancer: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, M.; Katnoria, J.K.; Nagpal, A.K. Polyphenols in Food: Cancer Prevention and Apoptosis Induction. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 4740–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayi, T.; Oniz, A. Effects of the Mediterranean diet polyphenols on cancer development. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E74–E80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, R.; Ballini, A.; Santacroce, L.; Cantore, S.; Inchingolo, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Di Domenico, M.; Quagliuolo, L.; Boccellino, M. Another Look at Dietary Polyphenols: Challenges in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 1061–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, S.; Pradhan, B.; Nayak, R.; Behera, C.; Das, S.; Patra, S.K.; Efferth, T.; Jena, M.; Bhutia, S.K. Dietary polyphenols in chemoprevention and synergistic effect in cancer: Clinical evidences and molecular mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 384S–392S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.; Fang, X.; Yang, J.; Yao, Y.; Nandakumar, K.S.; Salem, M.L.; Cheng, K. Recent Research on Flavonoids and their Biomedical Applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 1042–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Valko, R.; Liska, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Flavonoids and their role in oxidative stress, inflammation, and human diseases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2025, 413, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, J.N.; Mumtaz, S. Prunin: An Emerging Anticancer Flavonoid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sabella, H.; Mandlem, V.K.K.; Deba, F. Salvianolic acid-A alleviates oxidative stress-induced osteoporosis. Life Sci. 2025, 375, 123727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, C.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, Y.J. Effect of Butein, a Plant Polyphenol, on Apoptosis and Necroptosis of Prostate Cancer Cells in 2D and 3D Cultures. Life 2025, 15, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecka-Kroplewska, K.; Kmiec, Z.; Zmijewski, M.A. The Interplay Between Autophagy and Apoptosis in the Mechanisms of Action of Stilbenes in Cancer Cells. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, M.; Li, B.; He, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, N.; He, J. Caffeic Acid Protects Against Ulcerative Colitis via Inhibiting Mitochondrial Apoptosis and Immune Overactivation in Drosophila. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 2157–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, P.; Taurisano, V.; Tommonaro, G.; Pasquale, V.; Jiménez, J.M.S.; de Pascual, S.; Poli, T.A.; Nicolaus, B. Biological Properties of Polyphenols Extracts from Agro Industry’s Wastes. Waste Biomass Valor. 2017, 9, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademosun, A.O. Citrus peels odyssey: From the waste bin to the lab bench to the dining table. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Tian, G.; DiMarco-Crook, C.; Gao, W.; Zhao, C.; Li, G.; Lian, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zheng, J. Efficiency of four different dietary preparation methods in extracting functional compounds from dried tangerine peel. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Li, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, O.; Huang, L.; Guo, L.; Gao, W. A review of chemical constituents and health-promoting effects of citrus peels. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirmi, S.; Ferlazzo, N.; Lombardo, G.E.; Maugeri, A.; Calapai, G.; Gangemi, S.; Navarra, M. Chemopreventive Agents and Inhibitors of Cancer Hallmarks: May Citrus Offer New Perspectives? Nutrients 2016, 8, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, V.; Nasso, R.; Di Donato, P.; Finore, I.; Poli, A.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R. Lemon Peel Polyphenol Extract Reduces Interleukin-6-Induced Cell Migration, Invasiveness, and Matrix Metalloproteinase-9/2 Expression in Human Gastric Adenocarcinoma MKN-28 and AGS Cell Lines. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, V.; De Rosa, M.; Di Donato, P.; Nasso, R.; D’Errico, A.; Cammarota, F.; Poli, A.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R. Inhibition of Interleukin-6-Induced Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 Expression and Invasive Ability of Lemon Peel Polyphenol Extract in Human Primary Colon Cancer Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcone, R.; D’Errico, A.; Nasso, R.; Rullo, R.; Poli, A.; Di Donato, P.; Masullo, M. Inhibition of Enzymes Involved in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Aβ1–40 Aggregation by Citrus limon Peel Polyphenol Extract. Molecules 2023, 28, 6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontifex, M.G.; Malik, M.M.A.H.; Connell, E.; Müller, M.; Vauzour, D. Citrus Polyphenols in Brain Health and Disease: Current Perspectives. Front Neurosci. 2021, 15, 640648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolaji, N.; Shammugasamy, B.; Schindeler, A.; Dong, Q.; Dehghani, F.; Valtchev, P. Citrus Peel Flavonoids as Potential Cancer Prevention Agents. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, A.; Reveglia, P.; Nasso, R.; Maugeri, A.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R.; Corso, G.; De Vendittis, E.; Rullo, R. Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Mediterranean Forage Crops on Cholinesterases and Amyloid Aggregation Relevant to Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, A.; Hobbs, M.; Meyn, R.E. Clonogenic Cell Survival Assay. Methods Mol. Med. 2005, 110, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jin, P.; Guan, Y.; Luo, M.; Wang, Y.; He, B.; Li, B.; He, K.; Cao, J.; Huang, C.; et al. Exploiting Polyphenol-Mediated Redox Reorientation in Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileo, A.M.; Miccadei, S. Polyphenols as Modulator of Oxidative Stress in Cancer Disease: New Therapeutic Strategies. Oxid. Med. Cell. Long. 2016, 2016, 6475624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajashekar, C. Dual Role of Plant Phenolic Compounds as Antioxidants and Prooxidants. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, K.U.; Sharma, D.; Fatma, H.; Yasin, D.; Alam, M.; Sami, N.; Ahmad, F.J.; Shamsi, A.; Rizvi, M.A. The Dual Role of Dietary Phytochemicals in Oxidative Stress: Implications for Oncogenesis, Cancer Chemoprevention, and ncRNA Regulation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiecki, A.; Roomi, M.W.; Kalinovsky, T.; Rath, M. Anticancer Efficacy of Polyphenols and Their Combinations. Nutrients 2016, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hołota, M.; Posmyk, M.M. Nature-Inspired Strategies in Cancer Management: The Potential of Plant Extracts in Modulating Tumour Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, T.; Bhattacharya, R. Phytochemicals modulate cancer aggressiveness: A review depicting the anticancer efficacy of dietary polyphenols and their combinations. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 7696–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Vikash Song, J.; Wang, J.; Yi, J.; Dong, W. Hesperetin Induces the Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells via Activating Mitochondrial Pathway by Increasing Reactive Oxygen Species. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2985–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.X.H.; Tan, L.T.; Goh, J.K.; Chan, K.G.; Pusparajah, P.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Nobiletin and Derivatives: Functional Compounds from Citrus Fruit Peel for Colon Cancer Chemoprevention. Cancers 2019, 11, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, P.; Hu, C.; Cheng, X. The role of reactive oxygen species in gastric cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Guo, L.; Sun, Z.; Yang, G.; Guo, J.; Chen, K.; Xiao, R.; Yang, X.; Sheng, L. Monoamine Oxidase A is a Major Mediator of Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Glycolysis in Gastric Cancer Progression. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8023–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, R.; Alsous, L.; Sabbah, D.A.; Gul, H.I.; Gul, M.; Bardaweel, S.K. Monoamine Oxidase (MAO)as a Potential Target for Anticancer Drug Design and Development. Molecules 2021, 26, 6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, A.; Nasso, R.; Di Maro, A.; Landi, N.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; D’Angelo, S.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R. Identification and Characterization of Neuroprotective Properties of Thaumatin-like Protein 1a from Annurca Apple Flesh Polyphenol Extract. Nutrients 2024, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasso, R.; Pagliara, V.; D’Angelo, S.; Rullo, R.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R. Annurca Apple Polyphenol Extract Affects Acetyl-Cholinesterase and Mono-Amine Oxidase In Vitro Enzyme Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuta, A.; Nasso, R.; Gisonna, A.; Iuliano, R.; Montesarchio, S.; Acampora, V.; Sepe, L.; Avagliano, A.; Arcone, R.; Arcucci, A.; et al. Celecoxib, a Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug, Exerts a Toxic Effect on Human Melanoma Cells Grown as 2D and 3D Cell Cultures. Life 2023, 13, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, A.; Cerchia, C.; Di Giovanni, C.; Granato, G.; Albano, F.; Romano, S.; De Vendittis, E.; Ruocco, M.R.; Lavecchia, A. Ligand-based chemoinformatic discovery of a novel small molecule inhibitor targeting CDC25 dual specificity phosphatases and displaying in vitro efficacy against melanoma cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 40202–40222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albano, F.; Arcucci, A.; Granato, G.; Romano, S.; Montagnani, S.; De Vendittis, E.; Ruocco, M.R. Markers of mitochondrial dysfunction during the diclofenac-induced apoptosis in melanoma cell lines. Biochimie 2013, 95, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, R.; Nasso, R.; D’Errico, A.; Biazzi, E.; Tava, A.; Landi, N.; Di Maro, A.; Masullo, M.; De Vendittis, E.; Arcone, R. Effect of polyphenolic extracts from leaves of Mediterranean forage crops on enzymes involved in the oxidative stress, and useful for alternative cancer treatments. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 15, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Type | µg/mL |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorogenic acid | Polyphenol | <LOQ * |

| p-Coumaric acid | “ | 4.36 ± 1.50 |

| Ferulic acid | “ | 7.70 ± 3.10 |

| Sinapic acid | “ | <LOQ |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | “ | 1.42 ± 0.17 |

| Gentisic acid | “ | <LOQ |

| Salicylic acid | “ | <LOQ |

| trans-2-Hydroxycinnamic acid | “ | 2.69 ± 0.56 |

| 3-Methoxyhydrocinnamic acid | “ | <LOD ** |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester | “ | <LOQ |

| Kaempferol | Flavonoid | 2.05 ± 0.84 |

| Myricetin | “ | 9.63 ± 0.01 |

| Diosmetin | “ | 0.13 ± 0.11 |

| Morin | “ | <LOQ |

| Chrysin | “ | <LOQ |

| (+/−)-Naringenin | “ | 0.70 ± 0.05 |

| Baicalin | “ | <LOD |

| Hesperidin | “ | 202.06 ± 14.5 |

| Rutin Hydrate | “ | 48.49 ± 1.14 |

| Daidezin | “ | <LOQ |

| Biochanin A | “ | <LOQ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nasso, R.; Rullo, R.; D’Errico, A.; Reveglia, P.; Lecce, L.; Poli, A.; Di Donato, P.; Corso, G.; De Vendittis, E.; Arcone, R.; et al. Citrus limon Peel Extract Modulates Redox Enzymes and Induces Cytotoxicity in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020598

Nasso R, Rullo R, D’Errico A, Reveglia P, Lecce L, Poli A, Di Donato P, Corso G, De Vendittis E, Arcone R, et al. Citrus limon Peel Extract Modulates Redox Enzymes and Induces Cytotoxicity in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020598

Chicago/Turabian StyleNasso, Rosarita, Rosario Rullo, Antonio D’Errico, Pierluigi Reveglia, Lucia Lecce, Annarita Poli, Paola Di Donato, Gaetano Corso, Emmanuele De Vendittis, Rosaria Arcone, and et al. 2026. "Citrus limon Peel Extract Modulates Redox Enzymes and Induces Cytotoxicity in Human Gastric Cancer Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020598

APA StyleNasso, R., Rullo, R., D’Errico, A., Reveglia, P., Lecce, L., Poli, A., Di Donato, P., Corso, G., De Vendittis, E., Arcone, R., & Masullo, M. (2026). Citrus limon Peel Extract Modulates Redox Enzymes and Induces Cytotoxicity in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020598