Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIβ: A Therapeutic Target for Contractile Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

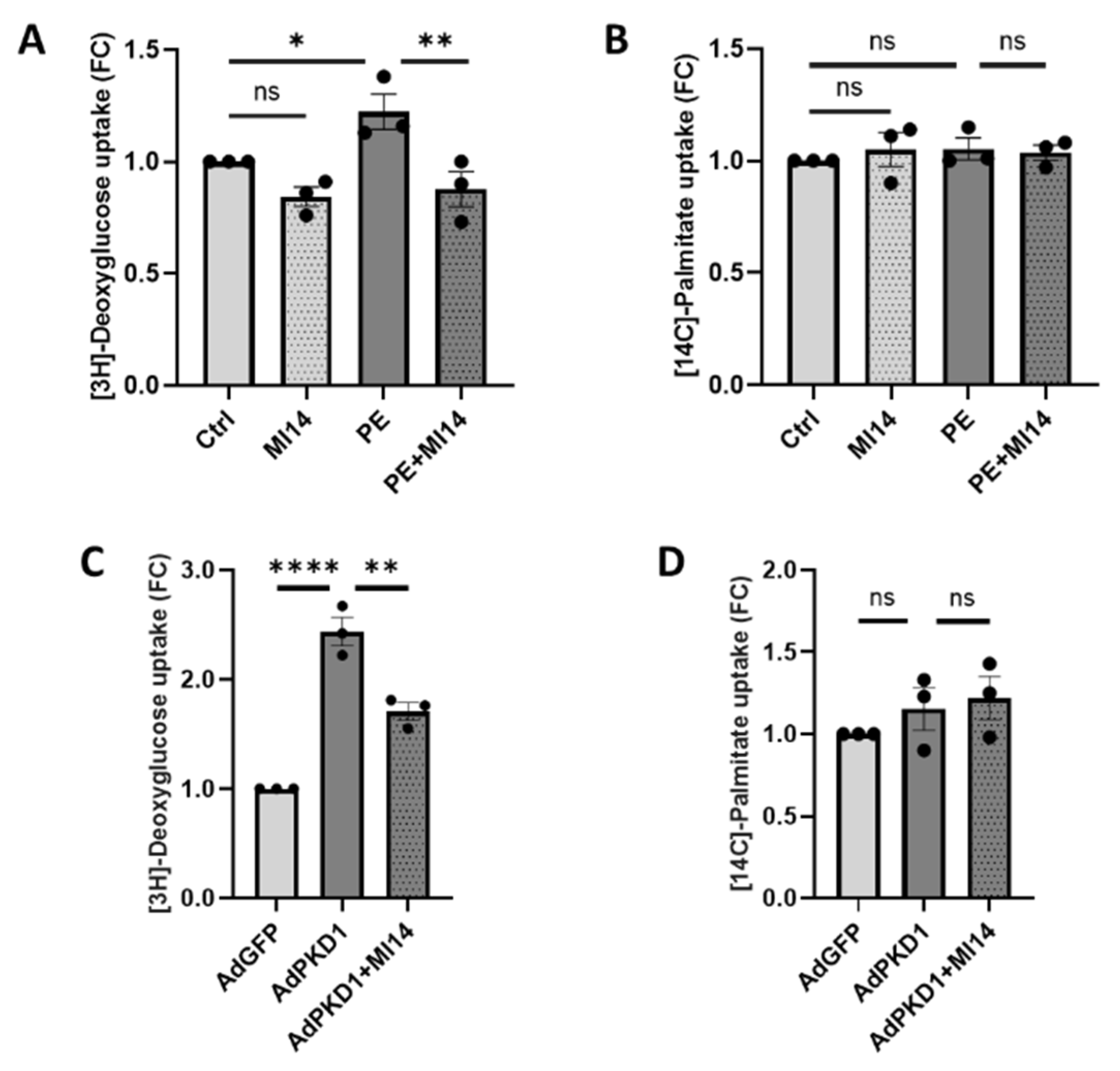

2.1. MI14 Prevents Phenylephrine-Induced Glucose Uptake in Adult Rat Cardiomyocytes

2.2. MI14 Does Not Prevent Phenylephrine-Induced Hypertrophic Signaling, Protein Synthesis and BNP Expression in Adult Rat Cardiomyocytes

2.3. MI14 Prevents Phenylephrine-Induced Contractile Dysfunction in Adult Rat Cardiomyocytes

2.4. MI14 Not Only Prevents, but Also Restores Glucose Uptake and Contractile Function in Adult Rat Cardiomyocytes

2.5. MI14 Lowers Phenylephrine-Induced Glucose Uptake in Human Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Isolation and Treatment of Adult Rat Cardiomyocytes

4.3. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes

4.4. RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

4.5. Cell Lysis and Western Blotting

4.6. Measurement of Substrate Uptake

4.7. Measurement of Phenylalanine Incorporation

4.8. Measurement of Contractile Function and Cardiomyocyte Size

4.9. Measurement of Cell Viability

4.10. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, S.C., Jr.; Collins, A.; Ferrari, R.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Logstrup, S.; McGhie, D.V.; Ralston, J.; Sacco, R.L.; Stam, H.; Taubert, K.; et al. Our time: A call to save preventable death from cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, L.H.; Commerford, P.J.; Gersh, B.J.; Pfeffer, M.A. Controversies in ventricular remodelling. Lancet 2006, 367, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, K.L.; McMullen, J.R. The athlete’s heart vs. the failing heart: Can signaling explain the two distinct outcomes? Physiology 2011, 26, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, N.; Olson, E.N. Cardiac hypertrophy: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003, 65, 45–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudbjarnason, S.; Telerman, M.; Chiba, C.; Wolf, P.L.; Bing, R.J. Myocardial Protein Synthesis in Cardiac Hypertrophy. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1964, 63, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Kemp, B.A.; Howell, N.L.; Massey, J.; Minczuk, K.; Huang, Q.; Chordia, M.D.; Roy, R.J.; Patrie, J.T.; Davogustto, G.E.; et al. Metabolic Changes in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat Hearts Precede Cardiac Dysfunction and Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e010926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, B.K.; Zhong, M.; Sen, S.; Davogustto, G.; Keller, S.R.; Taegtmeyer, H. Remodeling of glucose metabolism precedes pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy: Review of a hypothesis. Cardiology 2015, 130, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamirani, Y.S.; Kundu, B.K.; Zhong, M.; McBride, A.; Li, Y.; Davogustto, G.E.; Taegtmeyer, H.; Bourque, J.M. Noninvasive Detection of Early Metabolic Left Ventricular Remodeling in Systemic Hypertension. Cardiology 2016, 133, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.A.; Hill, B.G. Metabolic Coordination of Physiological and Pathological Cardiac Remodeling. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avkiran, M.; Rowland, A.J.; Cuello, F.; Haworth, R.S. Protein kinase d in the cardiovascular system: Emerging roles in health and disease. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek Papur, O.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Luiken, J. Protein kinase-D1 and downstream signaling mechanisms involved in GLUT4 translocation in cardiac muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, R.B.; Harrison, B.C.; Meadows, E.; Roberts, C.R.; Papst, P.J.; Olson, E.N.; McKinsey, T.A. Protein kinases C and D mediate agonist-dependent cardiac hypertrophy through nuclear export of histone deacetylase 5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 8374–8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Peng, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Su, G.; Zhao, Z. PKD knockdown inhibits pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy by promoting autophagy via AKT/mTOR pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monovich, L.; Vega, R.B.; Meredith, E.; Miranda, K.; Rao, C.; Capparelli, M.; Lemon, D.D.; Phan, D.; Koch, K.A.; Chapo, J.A.; et al. A novel kinase inhibitor establishes a predominant role for protein kinase D as a cardiac class IIa histone deacetylase kinase. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirkx, E.; Schwenk, R.W.; Coumans, W.A.; Hoebers, N.; Angin, Y.; Viollet, B.; Bonen, A.; van Eys, G.J.; Glatz, J.F.; Luiken, J.J. Protein kinase D1 is essential for contraction-induced glucose uptake but is not involved in fatty acid uptake into cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 5871–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, E.; van Eys, G.J.; Schwenk, R.W.; Steinbusch, L.K.; Hoebers, N.; Coumans, W.A.; Peters, T.; Janssen, B.J.; Brans, B.; Vogg, A.T.; et al. Protein kinase-D1 overexpression prevents lipid-induced cardiac insulin resistance. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 76, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Simsek Papur, O.; Dirkx, E.; Wong, L.; Sips, T.; Wang, S.; Strzelecka, A.; Nabben, M.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Neumann, D.; et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIβ mediates contraction-induced GLUT4 translocation and shows its anti-diabetic action in cardiomyocytes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 2839–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraets, I.M.E.; Coumans, W.A.; Strzelecka, A.; Schonleitner, P.; Antoons, G.; Schianchi, F.; Willemars, M.M.A.; Kapsokalyvas, D.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Luiken, J.; et al. Metabolic Interventions to Prevent Hypertrophy-Induced Alterations in Contractile Properties In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterhoff, J.; Young, S.; Villet, O.; Shao, D.; Neto, F.C.; Bettcher, L.F.; Hsu, Y.A.; Kolwicz, S.C., Jr.; Raftery, D.; Tian, R. Metabolic Remodeling Promotes Cardiac Hypertrophy by Directing Glucose to Aspartate Biosynthesis. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Ding, W.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zheng, N.; Liu, S.; Liu, J. Polydatin prevents hypertrophy in phenylephrine induced neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes and pressure-overload mouse models. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 746, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.J.; Gaitanaki, C.J.; Sugden, P.H. Effects of catecholamines on protein synthesis in cardiac myocytes and perfused hearts isolated from adult rats. Stimulation of translation is mediated through the α1-adrenoceptor. Biochem. J. 1990, 266, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, M.; McLeod, L.E.; Pratt, P.F.; Proud, C.G. Activation of protein synthesis in cardiomyocytes by the hypertrophic agent phenylephrine requires the activation of ERK and involves phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2). Biochem. J. 2005, 388, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorn, G.W., 2nd; Force, T. Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, K.M.; Brandenburger, Y.; Jenkins, A.; Sharkey, K.; Cavanaugh, A.; Rothblum, L.; Moss, T.; Poortinga, G.; McArthur, G.A.; Pearson, R.B.; et al. mTOR-dependent regulation of ribosomal gene transcription requires S6K1 and is mediated by phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal activation domain of the nucleolar transcription factor UBF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 8862–8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugden, P.H. Signaling in myocardial hypertrophy: Life after calcineurin? Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, J.; Basu, R.; McLean, B.A.; Das, S.K.; Zhang, L.; Patel, V.B.; Wagg, C.S.; Kassiri, Z.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Oudit, G.Y. Agonist-induced hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction are associated with selective reduction in glucose oxidation: A metabolic contribution to heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Y.; Bottcher, U.; Eblenkamp, M.; Thomas, J.; Jungling, E.; Rosen, P.; Kammermeier, H. Glucose transport and glucose transporter GLUT4 are regulated by product(s) of intermediary metabolism in cardiomyocytes. Biochem. J. 1997, 321, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, P.; Sharp, T.L.; Dence, C.; Haraden, B.M.; Gropler, R.J. Comparison of 1-(11)C-glucose and (18)F-FDG for quantifying myocardial glucose use with PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2002, 43, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liang, M.; Jin, S.; Wu, D.D.; Wang, M.J.; Zhu, Y.C. Hydrogen sulfide improves glucose metabolism and prevents hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Nitric Oxide 2015, 46, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansbury, B.E.; Riggs, D.W.; Brainard, R.E.; Salabei, J.K.; Jones, S.P.; Hill, B.G. Responses of hypertrophied myocytes to reactive species: Implications for glycolysis and electrophile metabolism. Biochem. J. 2011, 435, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.Y.; Walker, J.S.; Brown, R.D.; Moore, R.L.; Vinson, C.S.; Colucci, W.S.; Long, C.S. AFos inhibits phenylephrine-mediated contractile dysfunction by altering phospholamban phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 298, H1719–H1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejdrova, I.; Chalupska, D.; Kogler, M.; Sala, M.; Plackova, P.; Baumlova, A.; Hrebabecky, H.; Prochazkova, E.; Dejmek, M.; Guillon, R.; et al. Highly Selective Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIβ Inhibitors and Structural Insight into Their Mode of Action. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3767–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wong, L.Y.; Neumann, D.; Liu, Y.; Sun, A.; Antoons, G.; Strzelecka, A.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Nabben, M.; Luiken, J. Augmenting Vacuolar H+-ATPase Function Prevents Cardiomyocytes from Lipid-Overload Induced Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiazzi, A.; Mundina-Weilenmann, C.; Guoxiang, C.; Vittone, L.; Kranias, E. Role of phospholamban phosphorylation on Thr17 in cardiac physiological and pathological conditions. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 68, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guy, M.J.; Norman, H.S.; Chen, Y.C.; Xu, Q.; Dong, X.; Guner, H.; Wang, S.; Kohmoto, T.; Young, K.H.; et al. Top-down quantitative proteomics identified phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I as a candidate biomarker for chronic heart failure. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 4054–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Weeks, K.L.; Pretorius, L.; McMullen, J.R. Molecular distinction between physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: Experimental findings and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 128, 191–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Duncker, D.J.; Ya, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pavek, T.; Wei, H.; Merkle, H.; Ugurbil, K.; From, A.H.; Bache, R.J. Effect of left ventricular hypertrophy secondary to chronic pressure overload on transmural myocardial 2-deoxyglucose uptake. A 31P NMR spectroscopic study. Circulation 1995, 92, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Musi, N.; D’Agostino, J.; Hirshman, M.F.; Goodyear, L.J. Increased adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activity in rat hearts with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 2001, 104, 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagaya, Y.; Kanno, Y.; Takeyama, D.; Ishide, N.; Maruyama, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Ido, T.; Takishima, T. Effects of long-term pressure overload on regional myocardial glucose and free fatty acid uptake in rats. A quantitative autoradiographic study. Circulation 1990, 81, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimben, L.; Ingwall, J.S.; Lorell, B.H.; Pinz, I.; Schultz, V.; Tornheim, K.; Tian, R. Mechanisms for increased glycolysis in the hypertrophied rat heart. Hypertension 2004, 44, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, L.; Desalegn, T. Molecular mediators, characterization of signaling pathways with descriptions of cellular distinctions in pathophysiology of cardiac hypertrophy and molecular changes underlying a transition to heart failure. Int. J. Health Allied Sci. 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalupska, D.; Eisenreichova, A.; Rozycki, B.; Rezabkova, L.; Humpolickova, J.; Klima, M.; Boura, E. Structural analysis of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIβ (PI4KB)-14-3-3 protein complex reveals internal flexibility and explains 14-3-3 mediated protection from degradation in vitro. J. Struct. Biol. 2017, 200, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taegtmeyer, H.; Sen, S.; Vela, D. Return to the fetal gene program: A suggested metabolic link to gene expression in the heart. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1188, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J.F.C.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Larsen, T.S. Targeting metabolic pathways to treat cardiovascular diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okere, I.C.; Young, M.E.; McElfresh, T.A.; Chess, D.J.; Sharov, V.G.; Sabbah, H.N.; Hoit, B.D.; Ernsberger, P.; Chandler, M.P.; Stanley, W.C. Low carbohydrate/high-fat diet attenuates cardiac hypertrophy, remodeling, and altered gene expression in hypertension. Hypertension 2006, 48, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, R.W.; Dirkx, E.; Coumans, W.A.; Bonen, A.; Klip, A.; Glatz, J.F.; Luiken, J.J. Requirement for distinct vesicle-associated membrane proteins in insulin- and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-induced translocation of GLUT4 and CD36 in cultured cardiomyocytes. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, S.M. Nitrobenzylthioinosine-sensitive nucleoside transport system: Mechanism of inhibition by dipyridamole. Mol. Pharmacol. 1986, 30, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, A.; Abraham, R.; Diedrich, A.; Shibao, C.; Paranjape, S.Y.; Farley, G.; Biaggioni, I. Role of adenosine and nitric oxide on the mechanisms of action of dipyridamole. Stroke 2005, 36, 2170–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, S.; Vitacolonna, A.; Bonzano, A.; Comoglio, P.; Crepaldi, T. ERK: A Key Player in the Pathophysiology of Cardiac Hypertrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luiken, J.J.; van Nieuwenhoven, F.A.; America, G.; van der Vusse, G.J.; Glatz, J.F. Uptake and metabolism of palmitate by isolated cardiac myocytes from adult rats: Involvement of sarcolemmal proteins. J. Lipid Res. 1997, 38, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luiken, J.J.; Koonen, D.P.; Willems, J.; Zorzano, A.; Becker, C.; Fischer, Y.; Tandon, N.N.; Van Der Vusse, G.J.; Bonen, A.; Glatz, J.F. Insulin stimulates long-chain fatty acid utilization by rat cardiac myocytes through cellular redistribution of FAT/CD36. Diabetes 2002, 51, 3113–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Willemars, M.M.A.; Sun, A.; Wang, S.; Simsek Papur, O.; Brouns-Strzelecka, A.; van Leeuwen, R.; Vanherle, S.J.V.; Kapsokalyvas, D.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Neumann, D.; et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIβ: A Therapeutic Target for Contractile Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020595

Willemars MMA, Sun A, Wang S, Simsek Papur O, Brouns-Strzelecka A, van Leeuwen R, Vanherle SJV, Kapsokalyvas D, Glatz JFC, Neumann D, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIβ: A Therapeutic Target for Contractile Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020595

Chicago/Turabian StyleWillemars, Myrthe M. A., Aomin Sun, Shujin Wang, Ozlenen Simsek Papur, Agnieszka Brouns-Strzelecka, Rick van Leeuwen, Sabina J. V. Vanherle, Dimitrios Kapsokalyvas, Jan F. C. Glatz, Dietbert Neumann, and et al. 2026. "Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIβ: A Therapeutic Target for Contractile Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyocytes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020595

APA StyleWillemars, M. M. A., Sun, A., Wang, S., Simsek Papur, O., Brouns-Strzelecka, A., van Leeuwen, R., Vanherle, S. J. V., Kapsokalyvas, D., Glatz, J. F. C., Neumann, D., Nabben, M., & Luiken, J. J. F. P. (2026). Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIβ: A Therapeutic Target for Contractile Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020595