Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin in an Ex Vivo Mouse Model of Early-Onset Liver Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

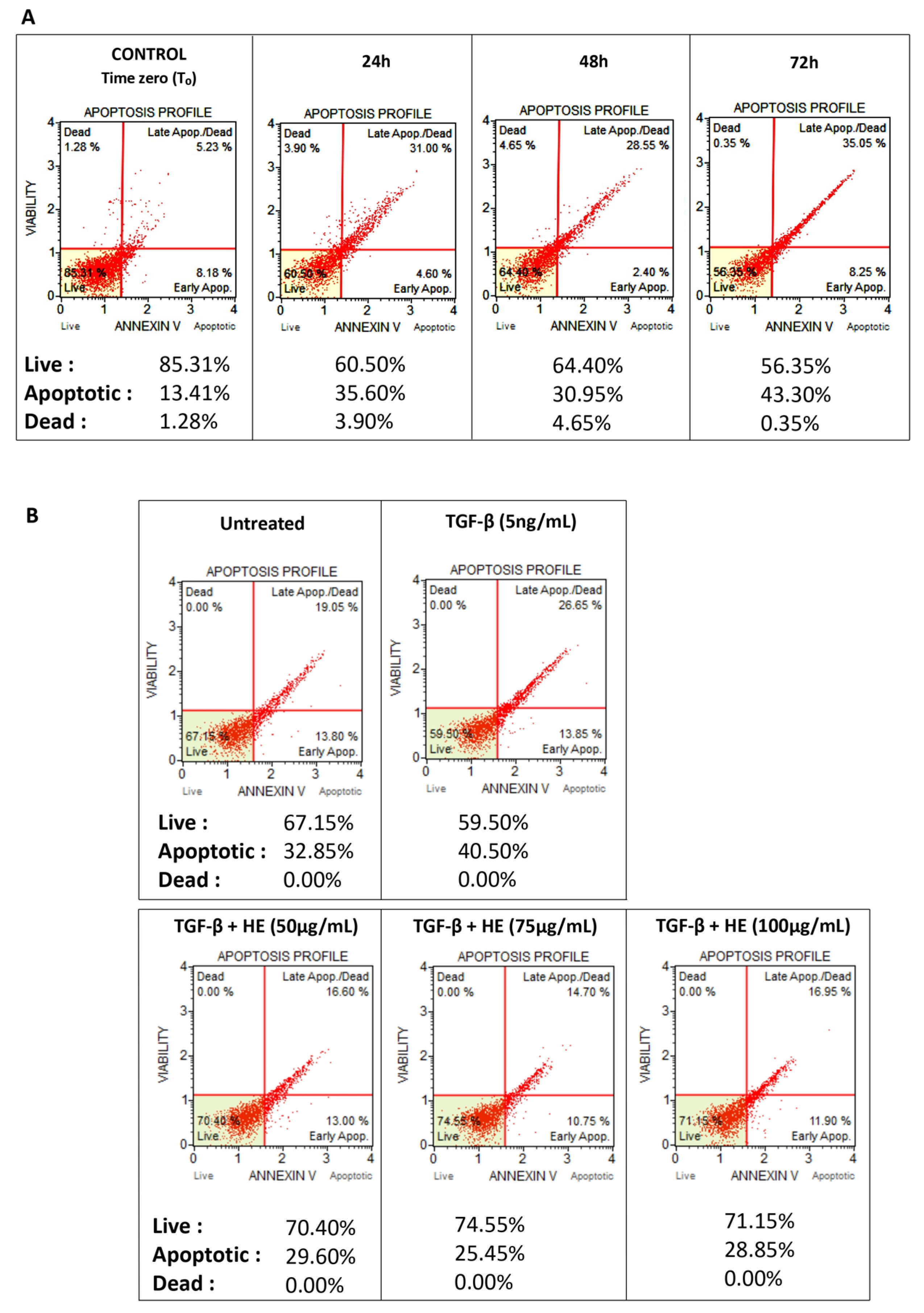

2.1. Viability of Hepatic Slices

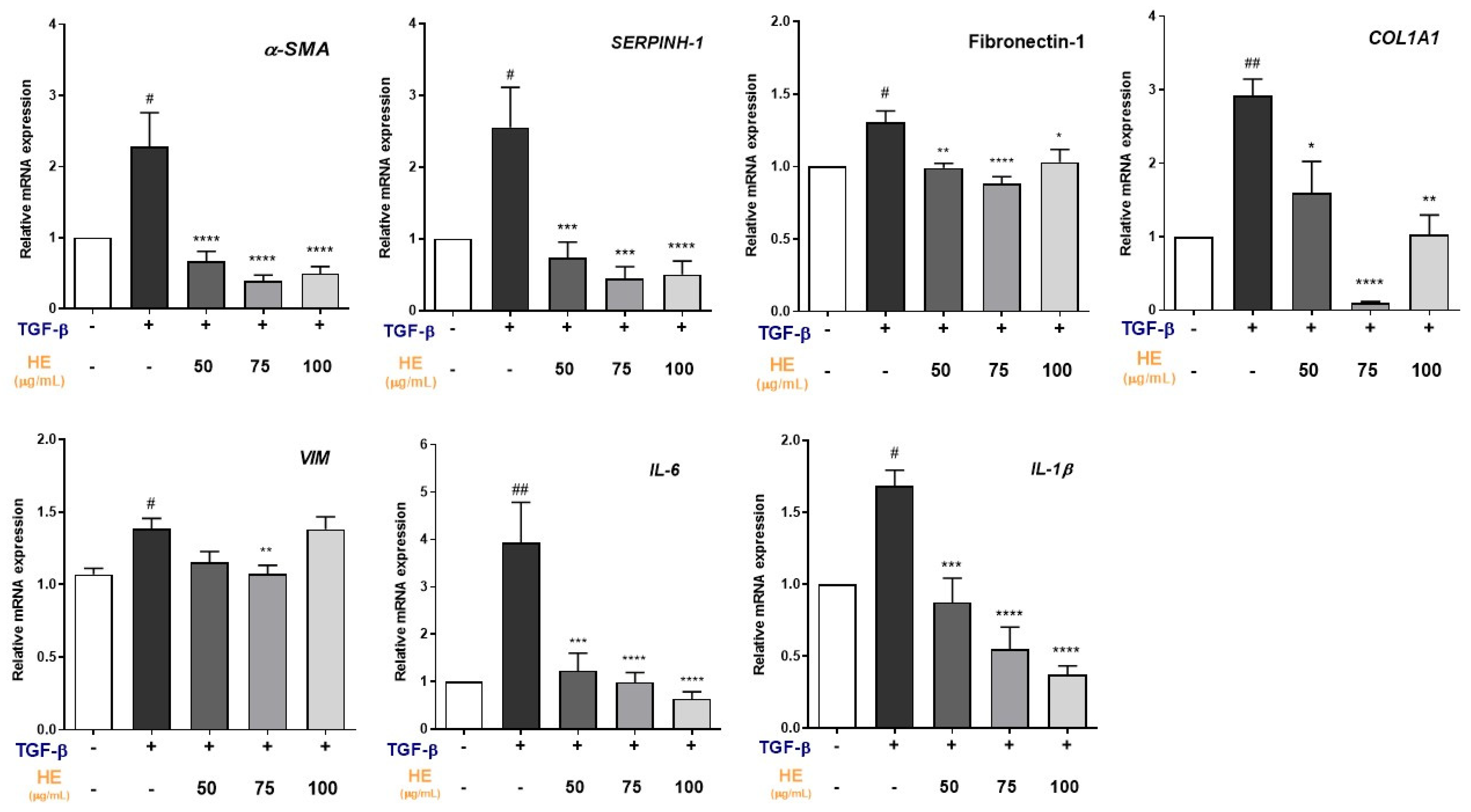

2.2. Effect of HE on TGF-β1-Induced Expression of Fibrosis and Inflammation-Related Genes

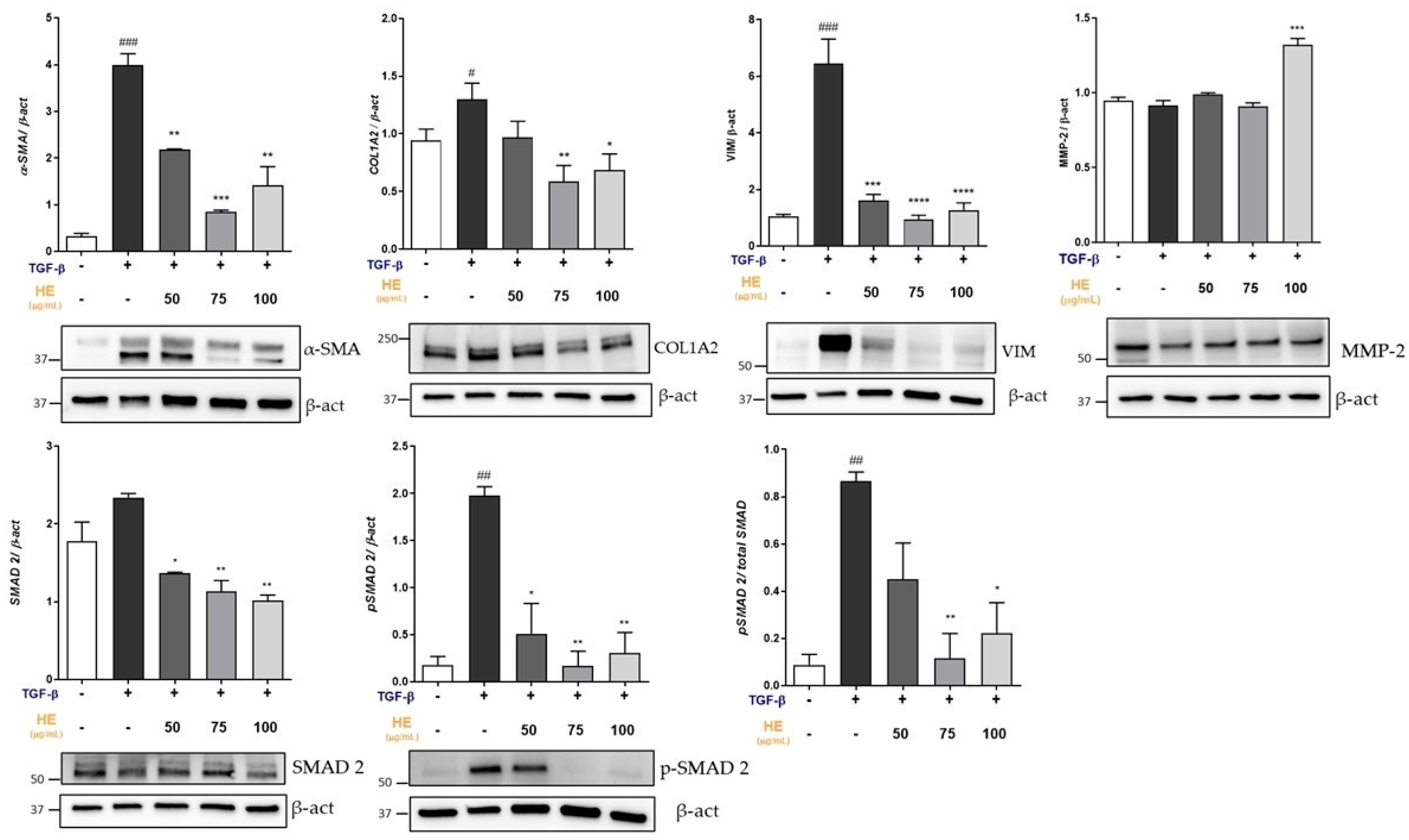

2.3. Effect of HE on Protein Expression of Key Mediators Involved in Fibrogenic Processes

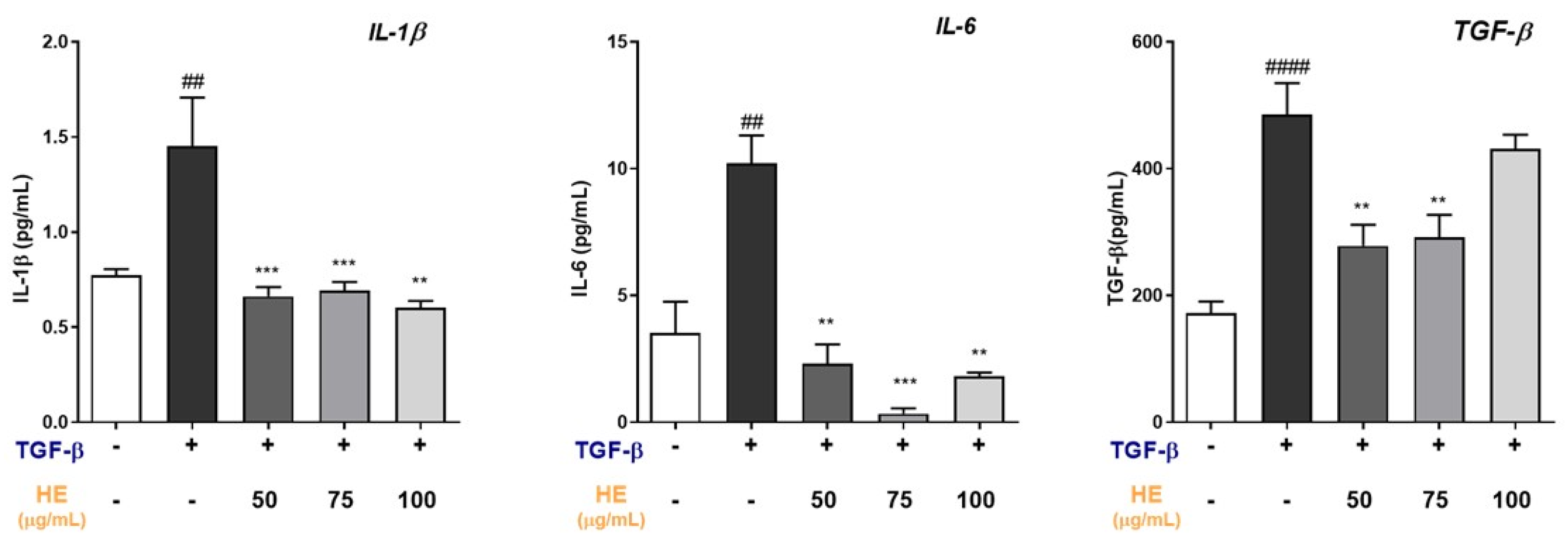

2.4. HE Modulates Inflammatory and Profibrotic Cytokine Release in TGF-β-Treated Hepatic Slices

2.5. Protective Role of HE on TGF-β-Induced Liver Injury Assessed by H&E and Silver-Reticulin Impregnation Staining

2.6. Effect of HE on the Lipidomic Profile in Hepatic Slices

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Hepatic Slices Preparation and Experimental Treatment

4.2. Viability Assay

4.3. Histological Staining

4.4. Gene Expression Analysis by Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

4.5. Western Blot Analysis

4.6. Fatty Acid Extraction, Preparation of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters, and Fatty Acid Quantification from Tissue Samples

4.7. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HSCs | Hepatic stellate cells |

| α-SMA | Alpha Smooth Muscle Actin |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor beta 1 |

| pSMAD2 | Phosphorylated SMAD2 |

| SMAD2 | SMAD Family Member 2 |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| SI | Silver Impregnation |

| PCLSs | Precision-Cut Liver Slices |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| Hepa-RG | Human Hepatoma Cell Line |

| COL1A1 | Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain |

| COL1A2 | Collagen Type I Alpha 2 Chain |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| FN-1 | Fibronectin-1 |

| SERPINH-1 | Serpin Family H Member 1 |

| VIM | Vimentin |

| PI | Peroxidation index |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| MUFAs | Monounsaturated Fatty Acids |

| DGLA | Dihomo γ-linoleic acid |

| AA | Arachidonic Acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| GLA | Gamma-linolenic Acid |

| SCD1 | Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1 |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| HBSS | Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution |

| β-Actin | Beta-actin |

| RIPA buffer | RadioImmunoPrecipitation Assay buffer |

| CCl4 | Carbon Tetrachloride |

| BDL | Bile Duct Ligation |

| MMP.2 | Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 |

| MMP.9 | Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 1 |

| TIMP-2 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 2 |

| NPAs | NAFLD Promoting Agents |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

References

- Koyama, Y.; Brenner, D.A. Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorca-Guiliani, A.E.; Leeming, D.J.; Henriksen, K.; Mortensen, J.H.; Nielsen, S.H.; Anstee, Q.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Karsdal, M.A.; Schuppan, D. ECM Formation and Degradation during Fibrosis, Repair, and Regeneration. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Hepatic Inflammatory Responses in Liver Fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzani, M.; Rombouts, K.; Colagrande, S. Fibrosis in Chronic Liver Diseases: Diagnosis and Management. J. Hepatol. 2005, 42, S22–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junqueira, L.C.U.; Cossermelli, W.; Brentani, R. Differential Staining of Collagens Type I, II and III by Sirius Red and Polarization Microscopy. Arch. Histol. Jpn. 1978, 41, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchtler, H.; Waldrop, F.S. Silver Impregnation Methods for Reticulum Fibers and Reticulin: A Re-Investigation of Their Origins and Specifity. Histochemistry 1978, 57, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-García, C.; Fernández-Iglesias, A.; Gracia-Sancho, J.; Arráez-Aybar, L.A.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; Cubero, F.J. The Space of Disse: The Liver Hub in Health and Disease. Livers 2021, 1, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L. Hepatic Stellate Cells: Protean, Multifunctional, and Enigmatic Cells of the Liver. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 125–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostallari, E.; Schwabe, R.F.; Guillot, A. Inflammation and Immunity in Liver Homeostasis and Disease: A Nexus of Hepatocytes, Nonparenchymal Cells and Immune Cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1205–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, G.; Mikulits, W.; Dooley, S.; Fabregat, I.; Moustakas, A.; ten Dijke, P.; Portincasa, P.; Winter, P.; Janssen, R.; Leporatti, S.; et al. The Rationale for Targeting TGF-β in Chronic Liver Diseases. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 46, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, I.M.; Oosterhuis, D.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Olinga, P. The Effect of Antifibrotic Drugs in Rat Precision-Cut Fibrotic Liver Slices. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Bovenkamp, M.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Meijer, D.K.F.; Olinga, P. Precision-Cut Fibrotic Rat Liver Slices as a New Model to Test the Effects of Anti-Fibrotic Drugs in Vitro. J. Hepatol. 2006, 45, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Leaker, B.; Qiao, G.; Sojoodi, M.; Eissa, I.R.; Epstein, E.T.; Eddy, J.; Dimowo, O.; Lauer, G.M.; Qadan, M.; et al. Precision-Cut Liver Slices as an Ex Vivo Model to Evaluate Antifibrotic Therapies for Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perramón, M.; Macías-Herranz, M.; García-Pérez, R.; Jiménez, W.; Fernández-Varo, G. Precision-Cut Liver Slices: A Valuable Preclinical Tool for Translational Research in Liver Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerche-Langrand, C.; Toutain, H.J. Precision-Cut Liver Slices: Characteristics and Use for in Vitro Pharmaco-Toxicology. Toxicology 2000, 153, 221–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, I.M.; Pham, B.T.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Olinga, P. Evaluation of Fibrosis in Precision-Cut Tissue Slices. Xenobiotica 2013, 43, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paish, H.L.; Reed, L.H.; Brown, H.; Bryan, M.C.; Govaere, O.; Leslie, J.; Barksby, B.S.; Garcia Macia, M.; Watson, A.; Xu, X.; et al. A Bioreactor Technology for Modeling Fibrosis in Human and Rodent Precision-Cut Liver Slices. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada, S.; Pinya, S.; Martorell, M.; Capó, X.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A.; Sureda, A. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin from the Genus Citrus. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 25, 4929–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, P.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Sun, W. Hesperetin Ameliorates Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Inflammation via the PI3K/AKT-Nrf2-ARE Pathway in Oleic Acid-Induced HepG2 Cells and a Rat Model of High-Fat Diet-Induced NAFLD. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3898–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, K.-A. A Comparative Study of Hesperetin, Hesperidin and Hesperidin Glucoside: Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antibacterial Activities In Vitro. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasehi, Z.; Kheiripour, N.; Taheri, M.A.; Ardjmand, A.; Jozi, F.; Shahaboddin, M.E. Efficiency of Hesperidin against Liver Fibrosis Induced by Bile Duct Ligation in Rats. Biomed. Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 5444301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.; Tuli, H.S.; Thakral, F.; Singhal, P.; Aggarwal, D.; Srivastava, S.; Pandey, A.; Sak, K.; Varol, M.; Khan, M.A.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Hesperidin in Cancer: Recent Trends and Advancements. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennen, L.I.; Walker, R.; Bennetau-Pelissero, C.; Scalbert, A. Risks and Safety of Polyphenol Consumption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 326S–329S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saponara, I.; Aloisio Caruso, E.; Cofano, M.; De Nunzio, V.; Pinto, G.; Centonze, M.; Notarnicola, M. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Fibrotic Effects of a Mixture of Polyphenols Extracted from “Navelina” Orange in Human Hepa-RG and LX-2 Cells Mediated by Cannabinoid Receptor 2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofano, M.; Saponara, I.; De Nunzio, V.; Pinto, G.; Aloisio Caruso, E.; Centonze, M.; Notarnicola, M. Hesperidin Is a Promising Nutraceutical Compound in Counteracting the Progression of NAFLD In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugger, M.; Laschinger, M.; Lampl, S.; Schneider, A.; Manske, K.; Esfandyari, D.; Hüser, N.; Hartmann, D.; Steiger, K.; Engelhardt, S.; et al. High Precision-Cut Liver Slice Model to Study Cell-Autonomous Antiviral Defense of Hepatocytes within Their Microenvironment. JHEP Rep. 2022, 4, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, I.M.; Mutsaers, H.A.M.; Luangmonkong, T.; Hadi, M.; Oosterhuis, D.; de Jong, K.P.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Olinga, P. Human Precision-Cut Liver Slices as a Model to Test Antifibrotic Drugs in the Early Onset of Liver Fibrosis. Toxicol. Vitr. 2016, 35, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Cai, H.; Ammar, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ravi, K.; Thompson, J.; Jarai, G. Molecular Characterization of a Precision-Cut Rat Liver Slice Model for the Evaluation of Antifibrotic Compounds. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 316, G15–G24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaker, B.D.; Wang, Y.; Tam, J.; Anderson, R.R. Analysis of Culture and RNA Isolation Methods for Precision-Cut Liver Slices from Cirrhotic Rats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffert, C.S.; Duryee, M.J.; Bennett, R.G.; DeVeney, A.L.; Tuma, D.J.; Olinga, P.; Easterling, K.C.; Thiele, G.M.; Klassen, L.W. Exposure of Precision-Cut Rat Liver Slices to Ethanol Accelerates Fibrogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 299, G661–G668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouzeau-Girard, H.; Guyot, C.; Combe, C.; Moronvalle-Halley, V.; Housset, C.; Lamireau, T.; Rosenbaum, J.; Desmoulière, A. Effects of Bile Acids on Biliary Epithelial Cell Proliferation and Portal Fibroblast Activation Using Rat Liver Slices. Lab. Investig. 2006, 86, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Bovenkamp, M.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Draaisma, A.L.; Merema, M.T.; Bezuijen, J.I.; van Gils, M.J.; Meijer, D.K.F.; Friedman, S.L.; Olinga, P. Precision-Cut Liver Slices as a New Model to Study Toxicity-Induced Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation in a Physiologic Milieu. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 85, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, C.; Combe, C.; Clouzeau-Girard, H.; Moronvalle-Halley, V.; Desmoulière, A. Specific Activation of the Different Fibrogenic Cells in Rat Cultured Liver Slices Mimicking in Vivo Situations. Virchows Arch. 2007, 450, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, S.K.; Siddaraju, N.; Khan, K.M.; Vasamsetti, B.; Kumar, N.R.; Haridas, V.; Reddy, M.B.; Baggavalli, S.; Oommen, A.M.; Pralhada Rao, R. Developing an in Vitro Screening Assay Platform for Evaluation of Antifibrotic Drugs Using Precision-Cut Liver Slices. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2015, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Young, C.D.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.-J. Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling in Fibrotic Diseases and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, M.; Sang, Y.; Wei, L.; Dai, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. TGF-β Inhibitors: The Future for Prevention and Treatment of Liver Fibrosis? Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1583616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzler, S.; Lohse, A.W.; Keil, A.; Henninger, J.; Dienes, H.P.; Schirmacher, P.; Rose-John, S.; Meyer Zum Büschenfelde, K.H.; Blessing, M. TGF-Β1 in Liver Fibrosis: An Inducible Transgenic Mouse Model to Study Liver Fibrogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1999, 276, G1059–G1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbia, D.; Carpi, S.; Sarcognato, S.; Cannella, L.; Colognesi, M.; Scaffidi, M.; Polini, B.; Digiacomo, M.; Esposito Salsano, J.; Manera, C.; et al. The Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenol Oleocanthal Exerts Antifibrotic Effects in the Liver. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 715183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo, S.E.; Peduto, L. The Perivascular Origin of Pathological Fibroblasts. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.; Azar, A.; Sapir, G.; Gamliel, A.; Nardi-Schreiber, A.; Sosna, J.; Gomori, J.M.; Katz-Brull, R. Real-Time Ex-Vivo Measurement of Brain Metabolism Using Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milano, S.; Saponara, I.; Gerbino, A.; Lapi, D.; Lela, L.; Carmosino, M.; Dal Monte, M.; Bagnoli, P.; Svelto, M.; Procino, G. β3-Adrenoceptor as a New Player in the Sympathetic Regulation of the Renal Acid–Base Homeostasis. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1304375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | |||||

| TGF-β (5 ng/mL) | - | + | + | + | + |

| HE (μg/mL) | - | - | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Fatty Acid (%) | |||||

| Palmitic acid (C16:0) | 24.22 ± 1.51 | 23.32 ± 1.61 | 24.48 ± 1.33 | 22.34 ± 0.59 | 23.30 ± 0.20 |

| Stearic acid (C18:0) | 15.49 ± 1.24 | 15.46 ± 0.32 | 13.38 ± 0.46 * | 17.07 ± 0.44 | 14.70 ± 0.17 |

| Total SFAs | 42.09 ± 3.19 | 40.93 ± 1.46 | 40.15 ± 1.29 | 41.53 ± 0.47 | 39.88 ± 0.50 |

| Palmitoleic acid (C16:1n7) | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.015 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.03 |

| Oleic acid (C18:1n9) | 12.99 ± 0.25 | 14.09 ± 0.27 | 15.56 ± 0.30 ** | 13.29 ± 0.07 | 14.14 ± 0.94 |

| Vaccenic acid (C18:1n7) | 2.585 ± 0.39 | 2.95 ± 0.15 | 2.54 ± 0.01 | 2.90 ± 0.01 | 3.08 ± 0.02 |

| Total MUFAs | 19.05 ± 0.52 | 20.51 ± 0.37 | 23.58 ± 0.35 *** | 20.13 ± 0.31 | 20.69 ± 0.78 |

| Linoleic acid (C18:2n6) | 13.83 ± 1.54 | 13.36 ± 1.44 | 14.80 ± 0.72 | 14.08 ± 1.85 | 13.18 ± 1.39 |

| GLA (C18:3n6) | 1.85 ± 3.31 | 1.01 ± 1.31 | 1.59 ± 1.45 | 0.57 ± 0.47 | 1.47 ± 1.26 |

| DGLA (C20:3n6) | 2.06 ± 0.23 | 1.94 ± 0.27 | 1.48 ± 0.09 * | 1.87 ± 0.20 | 1.91 ± 0.01 |

| AA (C20:4n6) | 11.01 ± 0.24 | 10.89 ± 1.26 | 8.977 ± 0.16 ** | 10.66 ± 0.24 | 11.27 ± 0.30 |

| EPA (C20:5n3) | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.96 ± 0.13 | 0.74 ± 0.04 * | 0.99 ± 0.14 | 0.99 ± 0.03 |

| DHA (C22:6n3) | 7.66 ± 0.88 | 8.53 ± 0.51 | 6.73 ± 0.21 *** | 7.36 ± 0.01 *** | 8.85 ± 0.08 |

| Total PUFAs | 39.09 ± 3.53 | 38.56 ± 1.24 | 36.28 ± 1.64 | 38.34 ± 0.16 | 39.44 ± 0.27 |

| Index | |||||

| PI | 126.8 ± 1.54 | 135.3 ± 1.95 ### | 112.5 ± 0.78 *** | 125.9 ± 1.57 *** | 133.1 ± 0.87 |

| SCD1 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.02 * | 1.00 ± 0.08 |

| Gene | Unique Assay ID | Chromosome Location | Amplicon Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-SMA | qMmuCID0006375 | 19:34246173-34248479 | 178 |

| COL1A1 | qMmuCID0021007 | 11:94936401-94937999 | 104 |

| SERPINH-1 | qMmuCID0022896 | 7:99347103-99348831 | 153 |

| Fibronectin-1 | qMmuCED0045687 | 1:71597314-71597404 | 61 |

| IL-1β | qMmuCID0005641 | 2:129366041-129367295 | 95 |

| IL-6 | qMmuCID0005613 | 5:30018087-30019454 | 112 |

| β-ACTIN | qMmuCED0027505 | 5:142904472-142904610 | 109 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saponara, I.; Cofano, M.; De Nunzio, V.; Bianco, G.; Armentano, R.; Pinto, G.; Aloisio Caruso, E.; Centonze, M.; Notarnicola, M. Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin in an Ex Vivo Mouse Model of Early-Onset Liver Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020594

Saponara I, Cofano M, De Nunzio V, Bianco G, Armentano R, Pinto G, Aloisio Caruso E, Centonze M, Notarnicola M. Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin in an Ex Vivo Mouse Model of Early-Onset Liver Fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020594

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaponara, Ilenia, Miriam Cofano, Valentina De Nunzio, Giusy Bianco, Raffaele Armentano, Giuliano Pinto, Emanuela Aloisio Caruso, Matteo Centonze, and Maria Notarnicola. 2026. "Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin in an Ex Vivo Mouse Model of Early-Onset Liver Fibrosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020594

APA StyleSaponara, I., Cofano, M., De Nunzio, V., Bianco, G., Armentano, R., Pinto, G., Aloisio Caruso, E., Centonze, M., & Notarnicola, M. (2026). Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hesperidin in an Ex Vivo Mouse Model of Early-Onset Liver Fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020594