Rational Design, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Chalcones as Dual-Acting Compounds—Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands and MAO-B Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

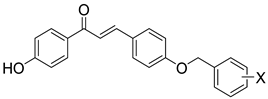

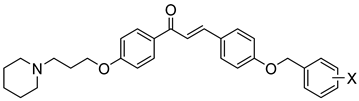

2.1. Design of Compounds

2.2. Synthesis of Compounds

2.3. Preliminary In Vitro Pharmacological Studies of Compounds

2.3.1. Human Histamine H3 Receptor Affinity

2.3.2. Functional Characterisation in cAMP Accumulation Assay of Selected Compounds

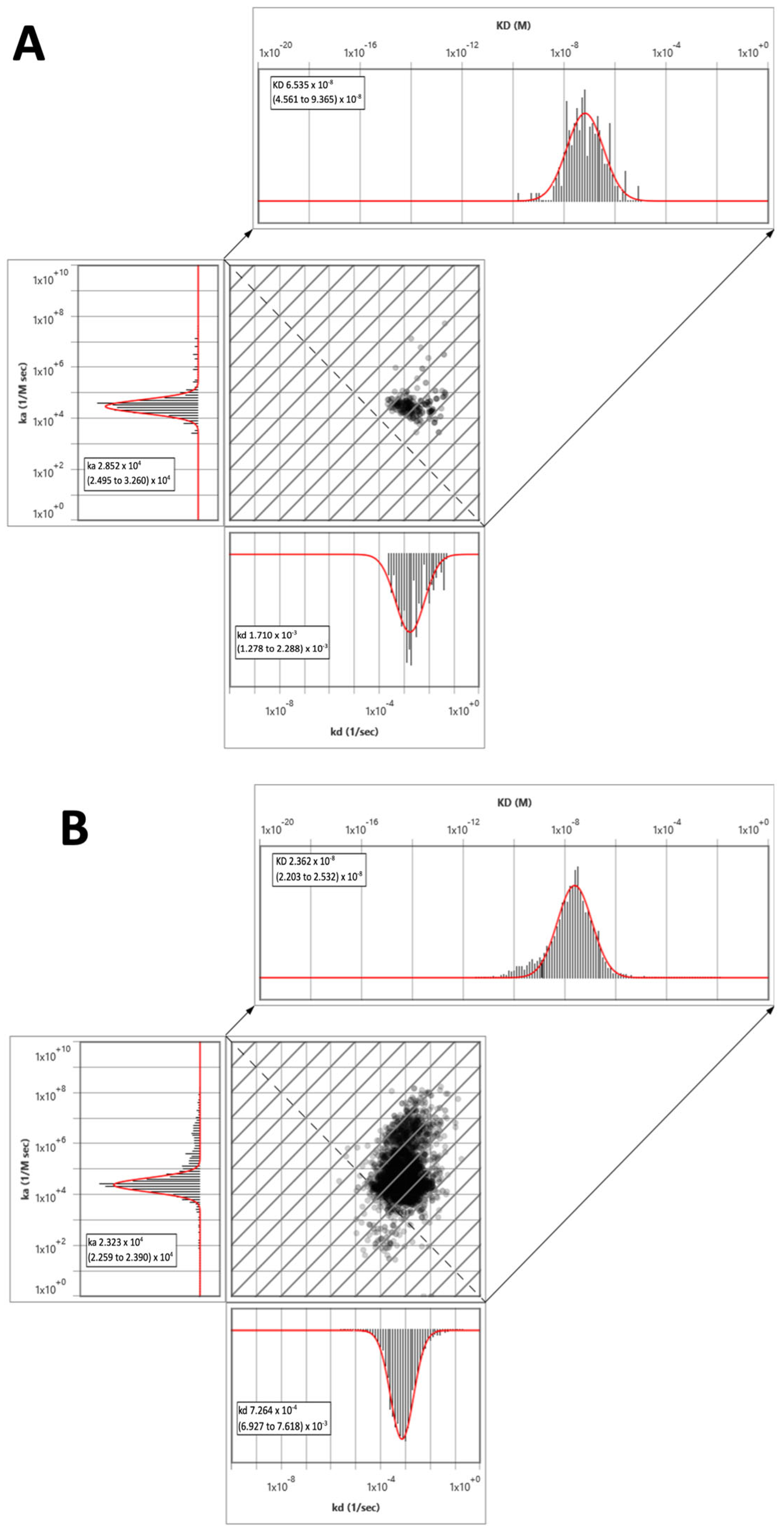

2.3.3. Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy Kinetic Studies of Selected Compounds

2.3.4. Human MAO-B Inhibitory Activity

2.3.5. Reversibility of Human MAO-B

2.3.6. Modality of Reversible Inhibition of Human MAO-B

2.3.7. Human MAO-A Inhibitory Activity

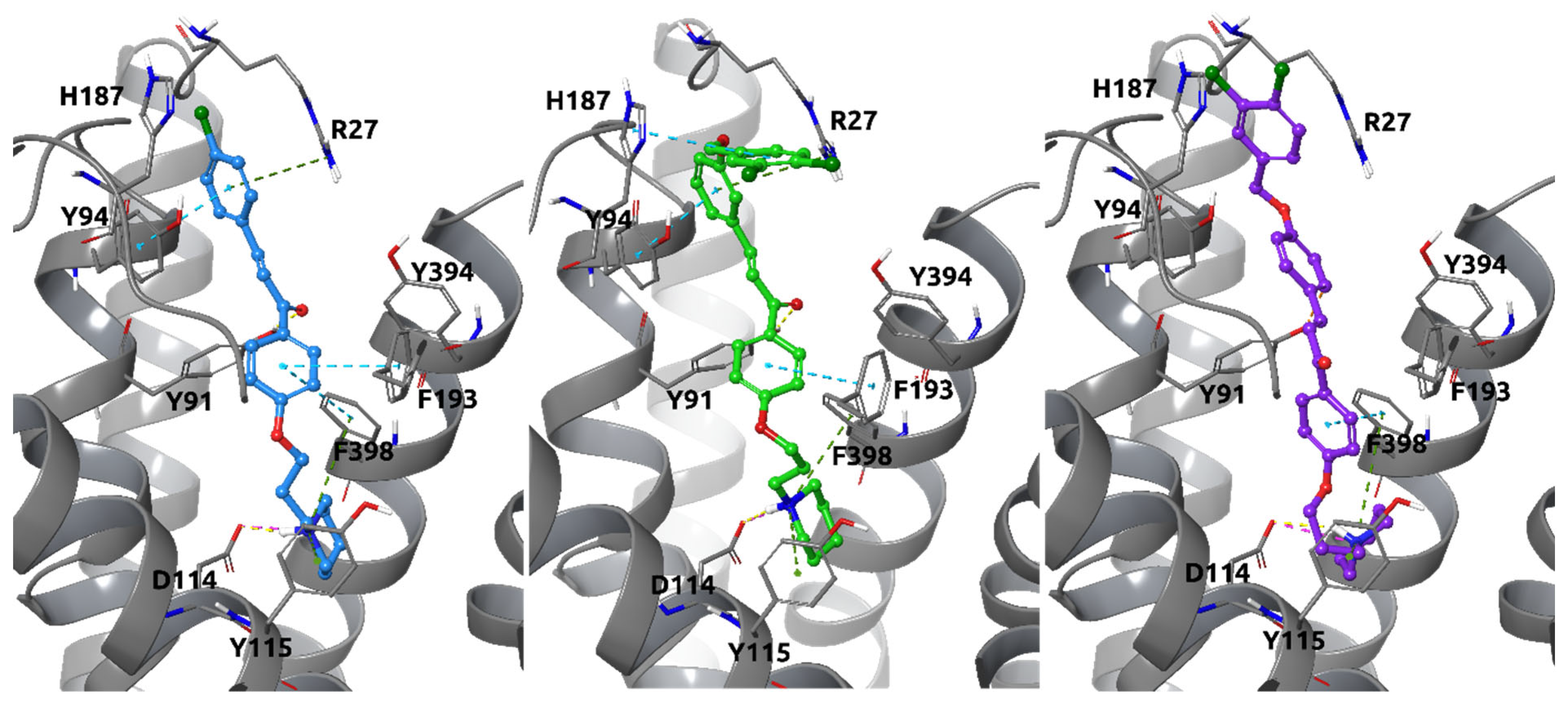

2.4. In Silico Docking Studies

2.4.1. Docking Studies to Histamine H3 Receptor

2.4.2. Docking Studies to Human MAO-B

2.5. Preliminary In Vitro ADMET Studies of Selected Compounds

2.5.1. Permeability Evaluation

2.5.2. Metabolic Stability

2.5.3. Preliminary Cell Toxicity

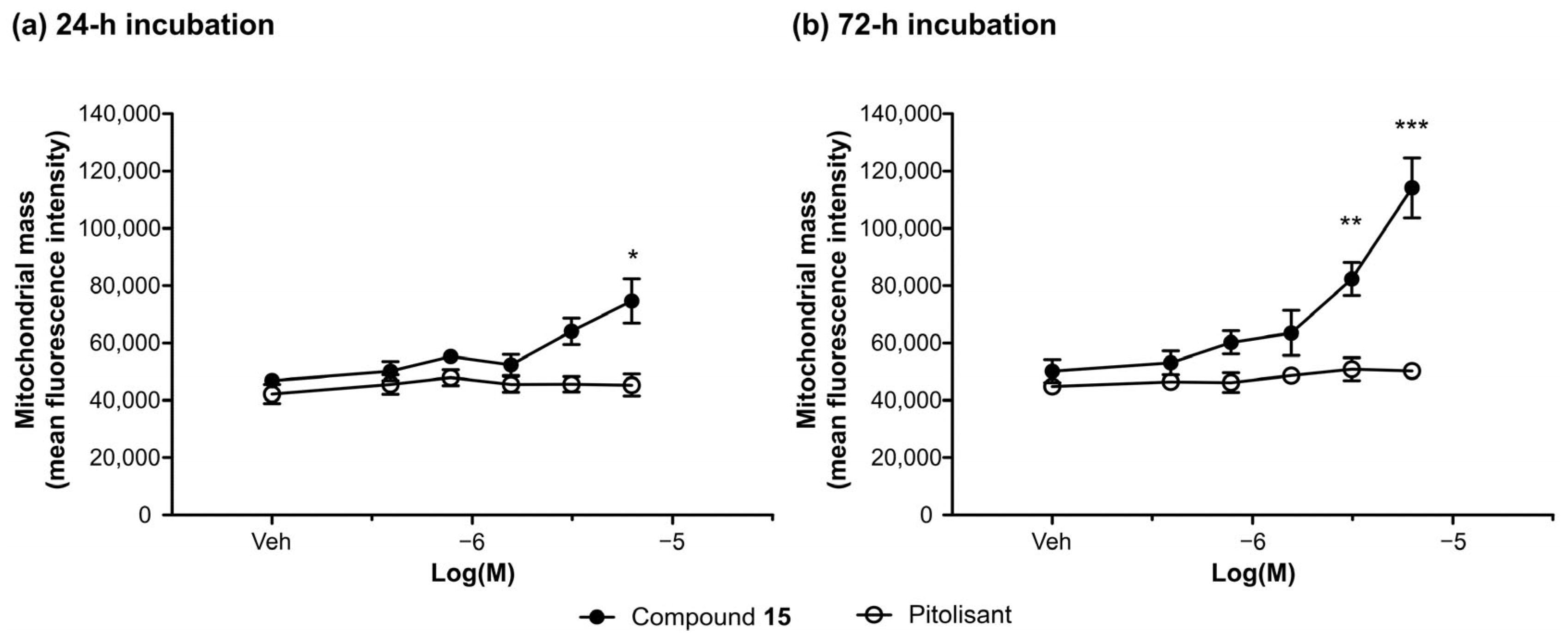

2.6. Activity Profile of Compound 15—In Vitro Studies

2.6.1. Effect of Compound 15 on Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Viability

2.6.2. Effect of Compound 15 on the Viability and Proliferation of the Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line (SH-SY5Y)

2.6.3. The Genotoxic Potential of Compound 15—Results from the Comet Assay

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. Synthesis of Starting Compounds

Synthesis of Benzyloxyaldehydes—General Method

Synthesis of 1-(4-(3-Bromo propoxy)phenyl)ethan-1-one (VI)

Synthesis of 1-(4-(3-Piperidin-1-yl)propoxy)phenyl)ethan-1-one (VII) (CAS256952-65-5)

3.1.2. General Method of Synthesis of Chalcones

3.2. In Vitro Biological Studies

3.2.1. Radioligand Binding Assay to Human Histamine H3 Receptor

3.2.2. Functional Assays for Histamine H3 Receptor

3.2.3. Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy (SPRM) Kinetic Studies

3.2.4. Human MAO-B and MAO-A Inhibitory Activity

3.2.5. Human MAO-B Reversibility Studies

3.2.6. Human MAO-B Kinetic Studies

3.3. Molecular Modelling Studies of the Histamine H3 Receptor and MAO-B

3.4. Preliminary ADMET Evaluation of Compounds 12 and 15

3.4.1. Permeability Evaluation

3.4.2. Metabolic Stability Studies

3.4.3. Drug–Drug Interaction Studies

3.4.4. Preliminary Cell Toxicity

3.5. Activity Profile of Compound 15—In Vitro Studies

3.5.1. Cell Culture

3.5.2. Cytotoxicity Assessment of Compound 15 and Its Effect on Cell Proliferation

Effect of Compound 15 on Human PBMCs Viability

Assessment of the Effect of Compound 15 on SH-SY5Y Cell Proliferation, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential, and Mitochondrial Mass (High Content Analysis Image Cytometry)

3.5.3. The Comet Assay—DNA Damage

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| Caco-2 | human colorectal cancer cell line |

| Clint | Clearance |

| cAMP | 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CYP | cytochrome |

| DA | dopamine |

| DCM | dichloromethane |

| DTLs | dual-target ligands |

| DX | doxorubicin |

| ER | efflux ratio |

| FAD | flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FC | flash chromatography |

| HepG2 | human liver cancer cell line |

| H3R | histamine H3 receptor |

| hH3R | human histamine H3 receptor |

| hMAO-A | human monoamine oxidase A |

| hMAO-B | human monoamine oxidase B |

| KE | ketoconazole |

| MAO-B | monoamine oxidase B |

| MLMs | mouse liver microsomes |

| MM-GBSA | Molecular Mechanics–Generalized Born Surface Area |

| NC | negative controls; untreated control |

| PAMPA | Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay |

| Papp | permeability coefficient |

| PBMCs | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| PC | positive control |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PEA | β-phenylethylamine |

| PFA | paraformaldehyde |

| RLMs | rat liver microsomes |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RT | residence time |

| SAF | Safinamide |

| SH-SY5Y | human neuroblastoma cell line |

| SPRM | Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy |

| QD | quinidine |

References

- Arrang, J.M.; Garbarg, M.; Schwartz, J.C. Autoinhibition of brain histamine release mediated by a novel class (H3) of histamine receptor. Nature 1983, 302, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panula, P.; Chazot, P.L.; Cowart, M.; Gutzmer, R.; Leurs, R.; Liu, W.L.; Stark, H.; Thurmond, R.L.; Haas, H.L. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVIII. Histamine Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 601–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiligada, E.; Ennis, M. Histamine pharmacology: From Sir Henry Dale to the 21st century. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurmond, R.L. The histamine H4 receptor: From orphan to the clinic. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovenberg, T.W.; Roland, B.L.; Wilson, S.J.; Jiang, X.; Pyati, J.; Huvar, A.; Jackson, M.R.; Erlander, M.G. Cloning and functional expression of the human histamine H3 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999, 55, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Dekker, M.E.; Leurs, R.; Vischer, H.F. Pharmacological characterization of seven human histamine H3 receptor isoforms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 968, 176450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łażewska, D.; Kieć-Kononowicz, K. Histamine H3 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists: A patent review (October 2017–December 2023) documenting progress. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2025, 35, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamari, N.; Zarei, O.; Arias-Montaño, J.A.; Reiner, D.; Dastmalchi, S.; Stark, H.; Hamzeh-Mivehroud, M. Histamine H3 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists: Where do they go? Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 200, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, K.; Kottke, T.; Stark, H. Histamine H3 receptor antagonists go to clinics. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 2163–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrang, J.M.; Morisset, S.; Gbahou, F. Constitutive activity of the histamine H3 receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlicker, E.; Kathmann, M. Role of the histamine H3 receptor in the central nervous system. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017, 241, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Y.N. Pitolisant: A review in narcolepsy with or without cataplexy. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ozawade (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Khanfar, M.A.; Affini, A.; Lutsenko, K.; Nikolic, K.; Butini, S.; Stark, H. Multiple targeting approaches on histamine H3 receptor antagonists. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.B.; Aranha, C.M.S.Q.; Fernandes, J.P.S. Histamine H3 receptor and cholinesterases as synergistic targets for cognitive decline: Strategies to the rational design of multitarget ligands. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szökő, É.; Tábi, T.; Riederer, P.; Vécsei, L.; Magyar, K. Pharmacological aspects of the neuroprotective effects of irreversible MAO-B inhibitors, selegiline and rasagiline, in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, W.H. A critical appraisal of MAO-B inhibitors in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2022, 129, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Wang, J.; Pisani, L.; Caccia, C.; Carotti, A.; Salvati, P.; Edmondson, D.E.; Mattevi, A. Structures of human monoamine oxidase B complexes with selective noncovalent inhibitors: Safinamide and coumarin analogs. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 5848–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affini, A.; Hagenow, S.; Zivkovic, A.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Stark, H. Novel indanone derivatives as MAO-B/H3R dual-targeting ligands for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 148, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsenko, K.; Hagenow, S.; Affini, A.; Reiner, D.; Stark, H. Rasagiline derivatives combined with histamine H3 receptor properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 126612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łażewska, D.; Olejarz-Maciej, A.; Kaleta, M.; Bajda, M.; Siwek, A.; Karcz, T.; Doroz-Płonka, A.; Cichoń, U.; Kuder, K.; Kieć-Kononowicz, K. 4-tert-Pentylphenoxyalkyl derivatives—Histamine H3 receptor ligands and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 3596–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łażewska, D.; Olejarz-Maciej, A.; Reiner, D.; Kaleta, M.; Latacz, G.; Zygmunt, M.; Doroz-Płonka, A.; Karcz, T.; Frank, A.; Stark, H.; et al. Dual Target Ligands with 4-tert-Butylphenoxy Scaffold as Histamine H3 Receptor Antagonists and Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łażewska, D.; Siwek, A.; Olejarz-Maciej, A.; Doroz-Płonka, A.; Wiktorowska-Owczarek, A.; Jóźwiak-Bębenista, M.; Reiner-Link, D.; Frank, A.; Sromek-Trzaskowska, W.; Honkisz-Orzechowska, E.; et al. Dual Targeting Ligands-Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands with Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitory Activity-In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, P.; Mathew, B.; Secci, D.; Carradori, S. Chalcones: Unearthing their therapeutic possibility as monoamine oxidase B inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 205, 112650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Królicka, E.; Kieć-Kononowicz, K.; Łażewska, D. Chalcones as Potential Ligands for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Jang, B.K.; Cho, N.C.; Park, J.H.; Yeon, S.K.; Ju, E.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Han, G.; Pae, A.N.; Kim, D.J.; et al. Synthesis of a series of unsaturated ketone derivatives as selective and reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 6486–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, F.; Fioravanti, R.; Bolasco, A.; Chimenti, P.; Secci, D.; Rossi, F.; Yáñez, M.; Orallo, F.; Ortuso, F.; Alcaro, S. Chalcones: A valid scaffold for monoamine oxidases inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2818–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkisz-Orzechowska, E.; Popiołek-Barczyk, K.; Linart, Z.; Filipek-Gorzała, J.; Rudnicka, A.; Siwek, A.; Werner, T.; Stark, H.; Chwastek, J.; Starowicz, K.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of new human histamine H3 receptor ligands with flavonoid structure on BV-2 neuroinflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 72, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, C.T.; Kim, G. SPR microscopy and its applications to high-throughput analyses of biomolecular binding events and their kinetics. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2380–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patching, S.G. Surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy for characterisation of membrane protein-ligand interactions and its potential for drug discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1838, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddy, D.M.; Cook, A.E.; Shackleford, D.M.; Pierce, T.L.; Mocaer, E.; Mannoury la Cour, C.; Sors, A.; Charman, W.N.; Summers, R.J.; Sexton, P.M.; et al. Drug-receptor kinetics and sigma-1 receptor affinity differentiate clinically evaluated histamine H3 receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology 2019, 144, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, D.; Stark, H. Ligand binding kinetics at histamine H3 receptors by fluorescence-polarization with real-time monitoring. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 848, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocking, T.A.M.; Verweij, E.W.E.; Vischer, H.F.; Leurs, R. Homogeneous, Real-Time NanoBRET Binding Assays for the Histamine H3 and H4 Receptors on Living Cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2018, 94, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Kumar, N.; Rathee, G.; Sood, D.; Singh, A.; Tomar, V.; Dass, S.K.; Chandra, R. Privileged Scaffold Chalcone: Synthesis, Characterization and Its Mechanistic Interaction Studies with BSA Employing Spectroscopic and Chemoinformatics Approaches. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 2267–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, R.A. Evaluation of Enzyme Inhibitors in Drug Discovery. A Guide for Medicinal Chemists and Pharmacologists; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-471-68696-4. [Google Scholar]

- Finberg, J.P.; Gillman, K. Selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type B and the “cheese effect”. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2011, 100, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Lou, S.; Mei, S.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. Structural basis for recognition of antihistamine drug by human histamine receptor. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, L.P.T.; Andreassen, S.N.; Caroli, J.; Rodríguez-Espigares, I.; Kermani, A.A.; Keserű, G.M.; Kooistra, A.J.; Pándy-Szekeres, G.; Gloriam, D.E. GPCRdb in 2025: Adding odorant receptors, data mapper, structure similarity search and models of physiological ligand complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D425–D435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipek, S. Molecular switches in GPCRs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 55, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansy, M.; Senner, F.; Gubernator, K. Physicochemical High Throughput Screening: Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay in the Description of Passive Absorption Processes. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breemen, R.B.; Li, Y. Caco-2 cell permeability assays to measure drug absorption. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2005, 1, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Stasiak, A.; Łażewska, D.; Sobierajska, K.; Kieć-Kononowicz, K.; Ciszewski, W.M. Targeting glioblastoma with hybrid H3R antagonists with piperidinylpropoxy and trimethoxychalcone motifs results in broad oncosuppressive effects. J. Drug Target. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Prusoff, W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger Release 2022-4: Schrödinger Suite 2024-4; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2024.

- Bowers, K.J.; Chow, E.; Xu, H.; Dror, R.O.; Eastwood, M.P.; Gregersen, B.A.; Klepeis, J.L.; Kolossvary, I.; Moraes, M.A.; Sacerdoti, F.D.; et al. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing SC’06, Tampa, FL, USA, 11–17 November 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, K.; Repasky, M.P.; Leswing, K.; Abel, R.; Shoichet, B.K.; Jerome, S.V. Efficient Exploration of Chemical Space with Docking and Deep Learning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 7106–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W.; Day, T.; Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Farid, R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Pincus, D.L.; Rapp, C.S.; Day, T.J.; Honig, B.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins 2004, 55, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomize, A.L.; Todd, S.C.; Pogozheva, I.D. Spatial arrangement of proteins in planar and curved membranes by PPM 3.0. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obach, R.S. Prediction of Human Clearance of Twenty-Nine Drugs from Hepatic Microsomal Intrinsic Clearance Data: An Examination of In Vitro Half-Life Approach and Nonspecific Binding to Microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1999, 27, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluska, M.; Juszczak, M.; Wysokiński, D.; Żuchowski, J.; Stochmal, A.; Woźniak, K. Kaempferol derivatives isolated from Lens culinaris Medik. reduce DNA damage induced by etoposide in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasiak, A.; Honkisz-Orzechowska, E.; Gajda, Z.; Wagner, W.; Popiołek-Barczyk, K.; Kuder, K.J.; Latacz, G.; Juszczak, M.; Woźniak, K.; Karcz, T.; et al. AR71, Histamine H3 Receptor Ligand-In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation (Anti-Inflammatory Activity, Metabolic Stability, Toxicity, and Analgesic Action). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Wilson, I.; Orton, T.; Pognan, F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 5421–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlach, S.; Wagner, W.; Podsędek, A.; Szewczyk, K.; Koziołkiewicz, M.; Dastych, J. Procyanidins from Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica) fruit induce apoptosis in human colon cancer Caco-2 cells in a degree of polymerisation-dependent manner. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Kania, K.D.; Ciszewski, W.M. Stimulation of lactate receptor (HCAR1) affects cellular DNA repair capacity. DNA Repair 2017, 52, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarz, P.; Piastowska-Ciesielska, A.W.; Kaarniranta, K.; Blasiak, J. All-Trans Retinoic Acid Modulates DNA Damage Response and the Expression of the VEGF-A and MKI67 Genes in ARPE-19 Cells Subjected to Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaad, I.; Abdel Rahman, D.M.A.; Al-Tamimi, O.; Alhaj, S.A.; Sabbah, D.A.; Hajjo, R.; Bardaweel, S.K. Targeting MAO-B with Small-Molecule Inhibitors: A Decade of Advances in Anticancer Research (2012–2024). Molecules 2024, 30, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sblano, S.; Boccarelli, A.; Mesiti, F.; Purgatorio, R.; de Candia, M.; Catto, M.; Altomare, C.D. A second life for MAO inhibitors? From CNS diseases to anticancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 267, 116180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauretta, P.; Martinez Vivot, R.; Velazco, A.; Medina, V.A. Histamine H3 receptor: An emerging target for cancer therapy? Inflamm. Res. 2025, 74, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, M.K.; Ahasan; Kaleem, M.; Raneem, E.; Gupta, A.; Amir, M.; Alam, M.M.; Akhter, M.; Tasneem, S.; Shaquiquzzaman, M. A comprehensive review of structure activity relationships: Exploration of chalcone derivatives as anticancer agents, target-based and cell line-specific insights. Med. Drug Discov. 2025, 28, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, M.I.; Barone, A.K.; Aungst, S.L.; Miller, C.P.; Ananthula, S.; Bi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Xiong, Y.; Fan, J.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Vorasidenib for IDH-Mutant Grade 2 Astrocytoma or Oligodendroglioma Following Surgery. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 4412–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comp. | X | hMAO-B a IC50 [nM] | Comp. | X | hH3R b Ki ± SEM [nM] | hMAO-B a IC50 ± SEM [nM] (% Inhibition) c | hMAO-A a (% Inhibition) d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | |||||||

| 1 | H | 96.0 ± 2.4 182 ± 5 f | 10 | H | 17.0 ± 2.2 | (18%) | nt e | |

| 2 | 4-Cl | 2.67 ± 0.35 31 ± 1 g | 11 | 4-Cl | 17.0 ± 0.5 | (36%) | nt e | |

| 3 | 3,4-diCl | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 12 | 3,4-diCl | 30.0 ± 0.9 | 500.0 ± 13.0 | (3%) | |

|  | |||||||

| 4 | H | 85.2 ± 2.4 | 13 | H | 80.6 ± 9.0 | (24%) | nt e | |

| 5 | 4-Cl | 33.4 ± 1.7 | 14 | 4-Cl | 54.0 ± 6.0 | 1121.4 ± 198.7 | (8%) | |

| 6 | 3,4-diCl | 20.6 ± 1.3 | 15 | 3,4-diCl | 46.8 ± 1.9 | 212.5 ± 12.3 | (22%) | |

|  | |||||||

| 7 | H | 287.5 ± 13.5 | 16 | H | 195.0 ± 13.0 | (33%) | nt e | |

| 8 | 4-Cl | 337.5 ± 17.1 | 17 | 4-Cl | 89.0 ± 4.0 | 1114.3 ± 317.0 | (0%) | |

| 9 | 3,4-diCl | 70.3 ± 4.5 | 18 | 3,4-diCl | 163.0 ± 12.0 | 355.9 ± 19.9 | (13%) | |

| safinamide | 8 ± 1 | |||||||

| rasagiline | 25 ± 6 | |||||||

| Compound | Affinity | Kinetics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD a ± SEM [nM] | KD b ± SEM [nM] | ka c ± SEM [×104 M−1 s −1] | kd d ± SEM [×10−3 s −1] | RT e ± SEM [min] | |

| DL76 | 39.2 ± 13.6 | 43.6 ± 12.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 16.0 ± 3.6 |

| Pitolisant | 15.0 ± 4.3 | 15.3 ± 4.7 | 7.9 ± 2.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 15.8 ± 3.0 |

| Parameter | Safinamide | Compound 15 |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity | Free enzyme > enzyme–substrate complex | Only free enzyme or free enzyme > enzyme–substrate complex |

| app. KM | ↑ curvilinearly with ↑ [I] | ↑ curvilinearly with ↑ [I] |

| app. Vmax | ↓ curvilinearly with ↑ [I] | ↓ curvilinearly with ↑ [I] |

| app. Vmax/app. KM | ↓ curvilinearly with ↑ [I] | ↓ curvilinearly with ↑ [I] |

| Lines on LB plot | Lines intersect to the left of the y-axis and above the x-axis | Lines intersect to the left of the y-axis and above the x-axis (almost on y-axis) |

| Mode of inhibition from kinetic values and LB plot | Mixed mode | Competitive/Mixed mode |

| Compound | Apparent Permeability (Papp) | Efflux Ratio (ER) a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Papp (A − B) ×10−6 cm/s ± SD | Papp (B − A) ×10−6 cm/s ± SD | ||

| 12 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.70 |

| 15 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.43 |

| Caffeine | 30.16 ± 2.94 | 34.80 ± 10.88 | 1.08 |

| Substrate | Metabolite | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mass (m/z) | Retention Time (min) | Molecular Mass (m/z) | Retention Time (min) | Metabolic Pathway |

| 12 (418.36) | 7.25 | 434.14 | 7.27 | hydroxylation |

| 15 (524.19) | 8.22 | 540.22 | 8.22 | hydroxylation |

| Compound | Clint a (mL/min/kg) | t0.5 b (min) | Metabolic Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 285.75 | 18.99 | weak/unstable |

| Verapamil | 239.5 | 22.60 | unstable |

| Incubation Time | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| PBM Cells | SH-SY5Y Cells | |

| 2 h | 80.30 | (-) |

| 24 h | 20.99 | 4.46 |

| 48 h | 14.25 | (-) |

| 72 h | 11.97 | 3.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Łażewska, D.; Doroz-Płonka, A.; Kuder, K.; Siwek, A.; Wagner, W.; Karnafał-Ziembla, J.; Olejarz-Maciej, A.; Wolak, M.; Głuch-Lutwin, M.; Mordyl, B.; et al. Rational Design, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Chalcones as Dual-Acting Compounds—Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands and MAO-B Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020581

Łażewska D, Doroz-Płonka A, Kuder K, Siwek A, Wagner W, Karnafał-Ziembla J, Olejarz-Maciej A, Wolak M, Głuch-Lutwin M, Mordyl B, et al. Rational Design, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Chalcones as Dual-Acting Compounds—Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands and MAO-B Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020581

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁażewska, Dorota, Agata Doroz-Płonka, Kamil Kuder, Agata Siwek, Waldemar Wagner, Joanna Karnafał-Ziembla, Agnieszka Olejarz-Maciej, Małgorzata Wolak, Monika Głuch-Lutwin, Barbara Mordyl, and et al. 2026. "Rational Design, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Chalcones as Dual-Acting Compounds—Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands and MAO-B Inhibitors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020581

APA StyleŁażewska, D., Doroz-Płonka, A., Kuder, K., Siwek, A., Wagner, W., Karnafał-Ziembla, J., Olejarz-Maciej, A., Wolak, M., Głuch-Lutwin, M., Mordyl, B., Osiecka, O., Juszczak, M., Woźniak, K., Więcek, M., Latacz, G., & Stasiak, A. (2026). Rational Design, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Chalcones as Dual-Acting Compounds—Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands and MAO-B Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020581