Targeting Melanin Production: The Safety of Tyrosinase Inhibition

Abstract

1. Introduction

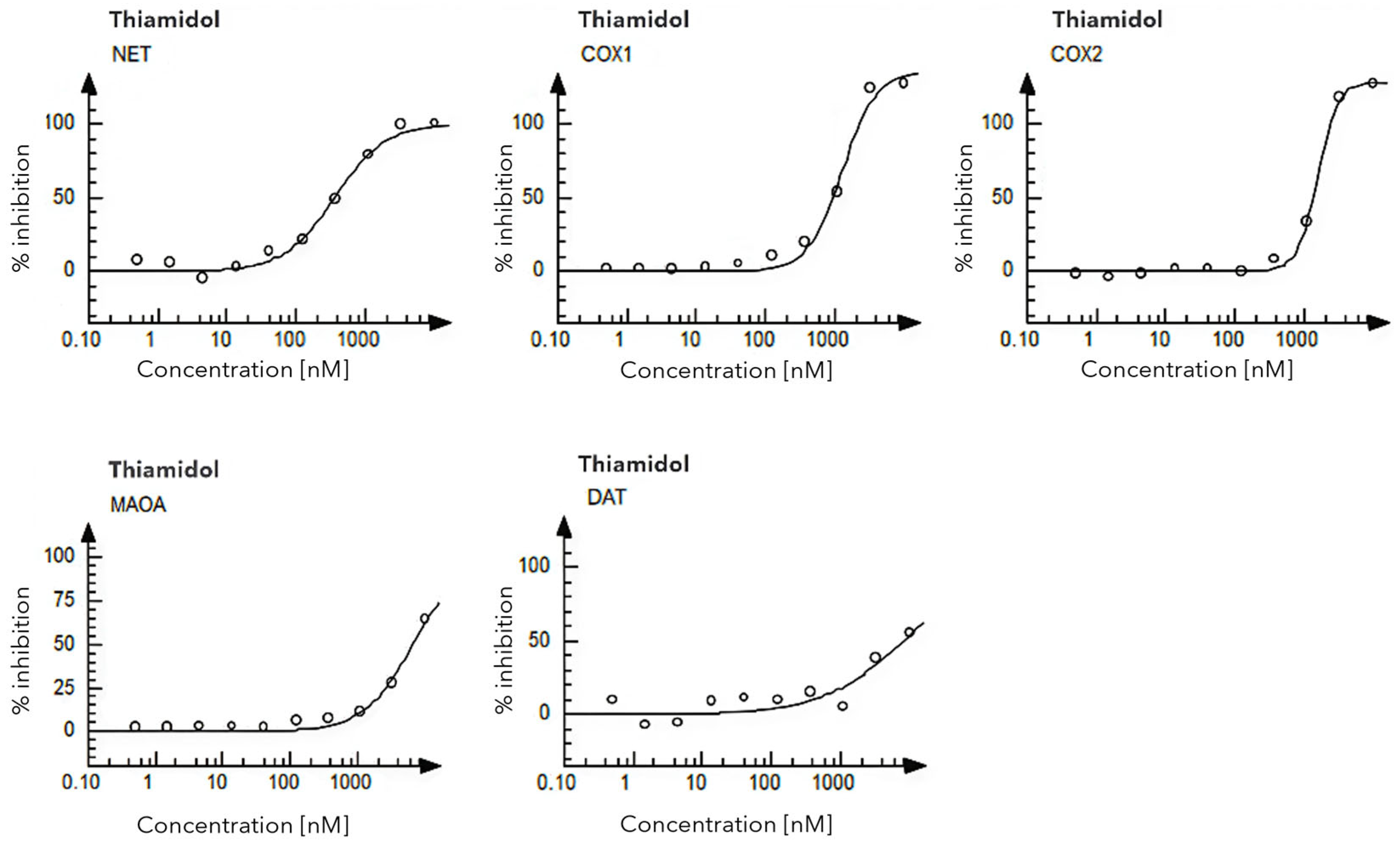

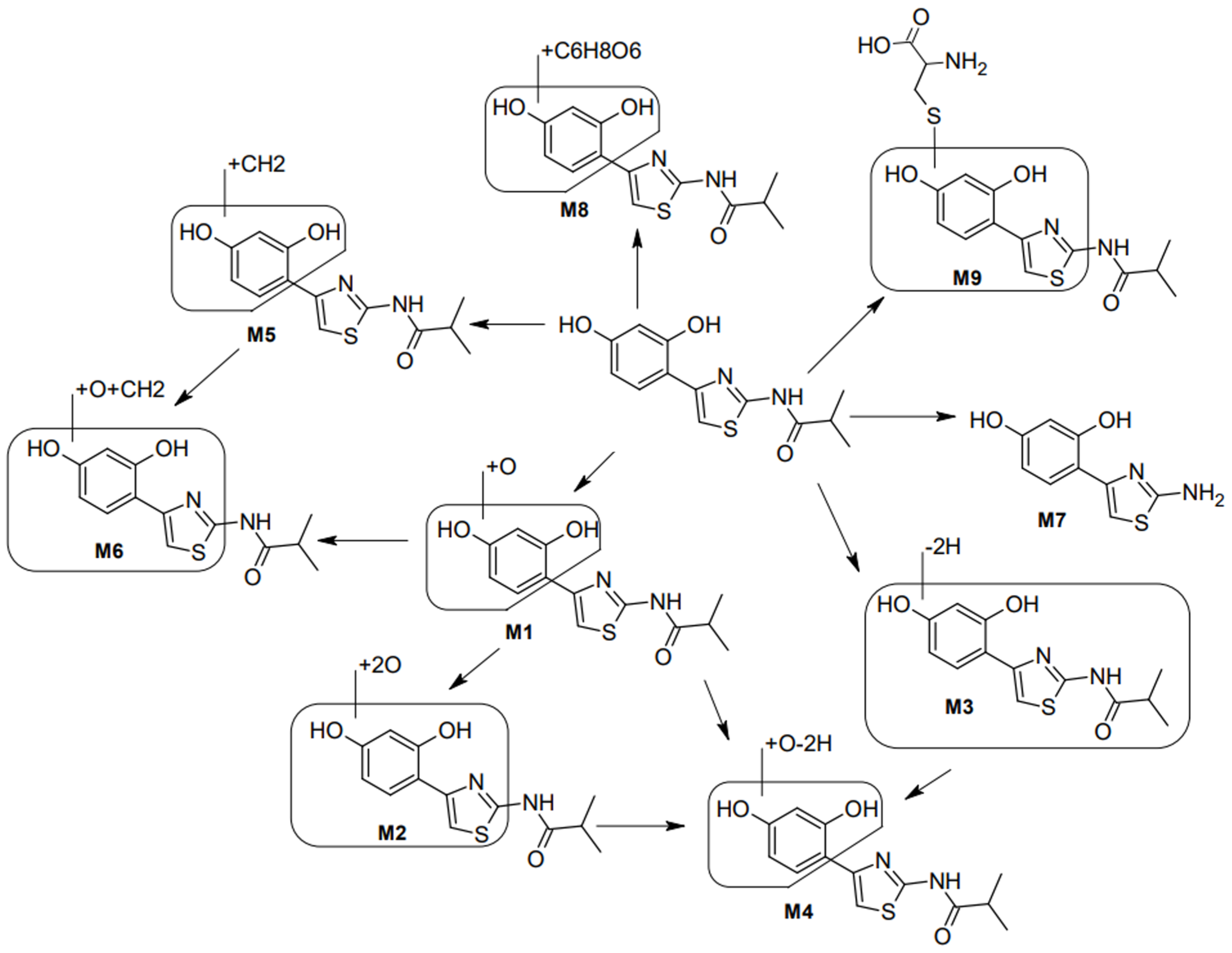

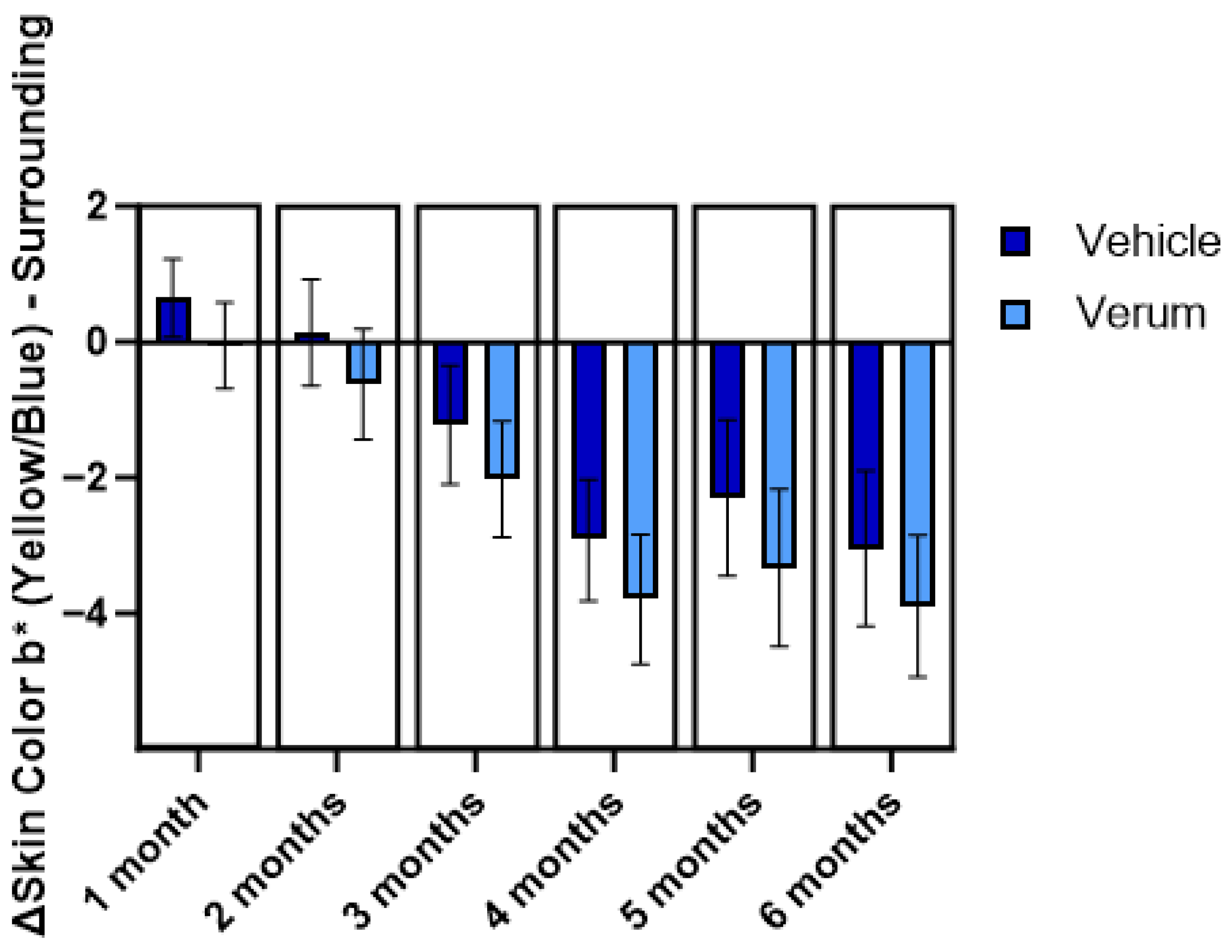

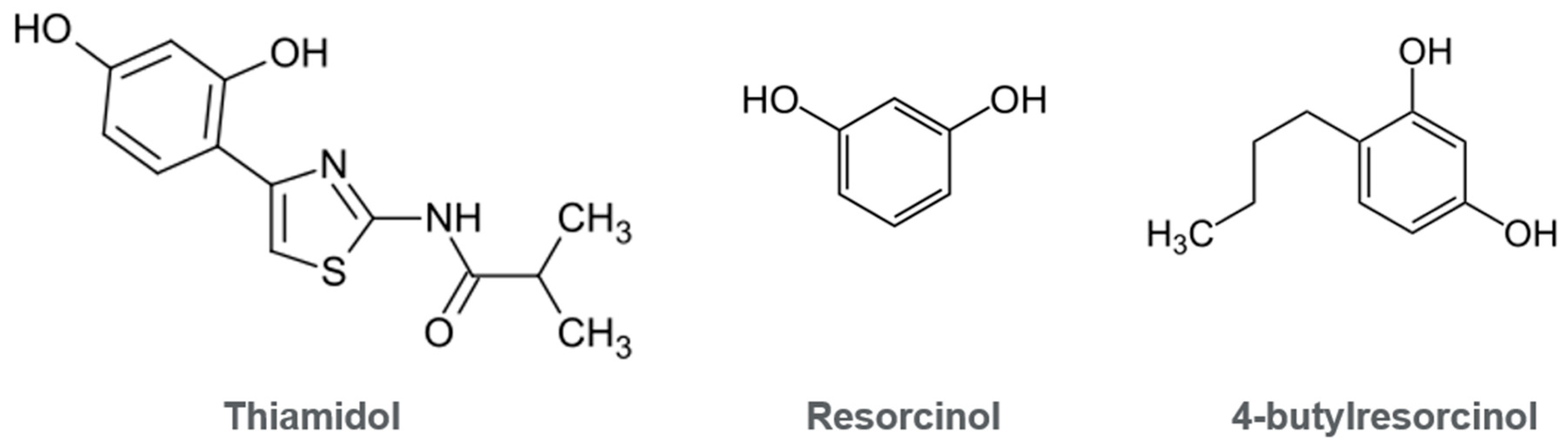

2. Result

2.1. Toxicology Evaluation

2.2. Exposure Assessment

2.3. Implications for Naevi Detection

3. Discussion

3.1. Toxicological Insights

3.2. Exclusion of Mechanisms Linked to Leukoderma and Ochronosis

3.3. Further Areas of Research and Limitations

3.4. Human Trials and Post-Market Surveillance

4. Material and Method

4.1. Toxicology Evaluation

4.2. Exposure Assessment

4.3. Investigation of Implications to Naevi Detection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient |

| DAT | Dopamine Transport |

| HRIPT | Human Repeat Insult Patch Test |

| hTyr | Human Tyrosinase |

| IC50 | Inhibitory Concentration |

| iTTC | Internal Threshold of Toxicological Concern |

| MOAO | Monoamine Oxidase A |

| NET | Norepinephrine Transport |

| NRU | Neutral Red Uptake |

| PBPK | Physiological-Based Pharmacokinetic |

| PIH | Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation |

| QSAR | Quantitative-Structure Activity Relationship |

References

- Hearing, V.J.; King, R.A. Determinants of skin color: Melanocytes and melanization. In Pigmentation and Pigmentary Abnormalities; Levine, N., Ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Chemistry of mixed melanogenesis—Pivotal roles of dopaquinone. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiberg, M. Keratinocyte–melanocyte interactions during melanosome transfer. Pigment. Cell Res. 2001, 14, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissy, R.E. Melanosome transfer to and translocation in the keratinocyte. Exp. Dermatol. 2003, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Hann, S.-K.; Im, S. Mixed Epidermal and Dermal Hypermelanoses and Hyperchromias. In The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology; Nordlund, J.J., Boissy, R.E., Hearing, V.J., King, R.A., Oetting, W.S., Ortonne, J.-P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, M.K. Genetic Epidermal Pigmentation with Lentigines. In The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology; Nordlund, J.J., Boissy, R.E., Hearing, V.J., King, R.A., Oetting, W.S., Ortonne, J.-P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ortonne, J.-P.; Nordlund, J.J. Mechanisms that Cause Abnormal Skin Color. In The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology; Nordlund, J.J., Boissy, R.E., Hearing, V.J., King, R.A., Oetting, W.S., Ortonne, J.-P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Balkrishnan, R.; McMichael, A.J.; Camacho, F.T.; Saltzberg, F.; Housman, T.S.; Grummer, S.; Feldman, S.R.; Chren, M.M. Development and validation of a health-related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maymone, M.B.C.; Neamah, H.H.; Wirya, S.A.; Patzelt, N.M.; Secemsky, E.A.; Zancanaro, P.Q.; Vashi, N.A. The impact of skin hyperpigmentation and hyperchromia on quality of life: A cross-sectional study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ferrer, A.; Rodríguez-López, J.N.; García-Cánovas, F.; García-Carmona, F. Tyrosinase: A comprehensive review of its mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1247, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.S.; Choi, H.; Rho, H.S.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, B.G.; Chang, I. Pigment-lightening effect of N,N’-dilinoleylcystamine on human melanoma cells. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, M.L.; Czyz, M. MITF in melanoma: Mechanisms behind its expression and activity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahhas, A.F.; Abdel-Malek, Z.A.; Kohli, I.; Braunberger, T.L.; Lim, H.W.; Hamzavi, I.H. The potential role of antioxidants in mitigating skin hyperpigmentation resulting from ultraviolet and visible light-induced oxidative stress. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2019, 35, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, S.; Nakano, M.; Tero-Kubota, S. Generation of superoxide during the enzymatic action of tyrosinase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 292, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.D.; Peles, D.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S. Current challenges in understanding melanogenesis: Bridging chemistry, biological control, morphology, and function. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.; Hearing, V.J. Modifying skin pigmentation—Approaches through intrinsic biochemistry and exogenous agents. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Mech. 2008, 5, e189–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakozaki, T.; Minwalla, L.; Zhuang, J.; Chhoa, M.; Matsubara, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Greatens, A.; Hillebrand, G.G.; Bissett, D.L.; Boissy, R.E. The effect of niacinamide on reducing cutaneous pigmentation and suppression of melanosome transfer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zeng, H.; Huang, J.; Lei, L.; Tong, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, H.; Khan, M.; Luo, L.; et al. Epigenetic regulation of melanogenesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 69, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennes, S.; Paschoalick, R.; Alchorne, M. A double-blind, comparative, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and tolerability of 4% hydroquinone as a depigmenting agent in melasma. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2000, 11, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penneys, N.S. Ochronosis like pigmentation from hydroquinone bleaching creams. Arch. Dermatol. 1985, 121, 1239–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.N.; Dhurat, R.S.; Deshpande, D.J.; Nayak, C.S. Diagnostic utility of dermatoscopy in hydroquinone-induced exogenous ochronosis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013, 52, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerhof, W.; Kooyers, T.J. Hydroquinone and its analogues in dermatology—A potential health risk. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2005, 4, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooyers, T.J.; Westerhof, W. Toxicology and health risks of hydroquinone in skin lightening formulations. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2005, 20, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dormael, R.; Bastien, P.; Sextius, P.; Gueniche, A.; Ye, D.; Tran, C.; Chevalier, V.; Gomes, C.; Souverain, L.; Tricaud, C. Vitamin C prevents ultraviolet-induced pigmentation in healthy volunteers: Bayesian meta-analysis results from 31 randomized controlled versus vehicle clinical studies. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2019, 12, E53–E59. [Google Scholar]

- Greatens, A.; Hakozaki, T.; Koshoffer, A.; Epstein, H.; Schwemberger, S.; Babcock, G.; Bissett, D.; Takiwaki, H.; Arase, S.; Wickett, R.R.; et al. Effective inhibition of melanosome transfer to keratinocytes by lectins and niacinamide is reversible. Exp. Dermatol. 2005, 14, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, J.C.; Varón, R.; Fenoll, L.G.; Gilabert, M.A.; García-Ruíz, P.A.; Tudela, J.; García-Cánovas, F. Kinetic characterization of the substrate specificity and mechanism of mushroom tyrosinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Molina, F.; Hiner, A.N.; Fenoll, L.G.; Rodríguez-Lopez, J.N.; García-Ruiz, P.A.; García-Cánovas, F.; Tudela, J. Mushroom tyrosinase: Catalase activity, inhibition, and suicide inactivation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3702–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, T.; Gerwat, W.; Batzer, J.; Eggers, K.; Scherner, C.; Wenck, H.; Stäb, F.; Hearing, V.J.; Röhm, K.H.; Kolbe, L. Inhibition of human tyrosinase requires molecular motifs distinctively different from mushroom tyrosinase. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Workshop Report on Operational and Financial Aspects of Validation; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 399; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Losada-Fernández, I.; San Martín, A.; Moreno-Nombela, S.; Suárez-Cabrera, L.; Valencia, L.; Pérez-Aciego, P.; Velasco, D. In vitro skin models for skin sensitisation: Challenges and future directions. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Defined Approaches on Skin Sensitisation; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, No. 497, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Jimenez, A.; Teruel-Puche, J.A.; Berna, J.; Rodriguez-Lopez, J.N.; Tudela, J.; Garcia-Ruiz, P.A.; Garcia-Canovas, F. Characterization of the action of tyrosinase on resorcinols. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 4434–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, F.; Tourneix, F.; Assaf Vandecasteele, H.; van Vliet, E.; Bury, D.; Alépée, N. Read-across can increase confidence in the Next Generation Risk Assessment for skin sensitisation: A case study with resorcinol. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 117, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, P.; Cole, T.; Curren, R.; Gibson, R.M.; Liebsch, M.; Raabe, H.; Tuomainen, A.M.; Whelan, M.; Kinsner-Ovaskainen, A. Assessment of the predictive capacity of the 3T3 Neutral Red Uptake cytotoxicity test method to identify substances not classified for acute oral toxicity (LD50 > 2000 mg/kg): Results of an ECVAM validation study. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowes, J.; Brown, A.J.; Hamon, J.; Jarolimek, W.; Sridhar, A.; Waldron, G.; Whitebread, S. Reducing safety-related drug attrition: The use of in vitro pharmacological profiling. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS). SCCS Notes of Guidance for the Testing of Cosmetic Ingredients and Their Safety Evaluation 12th Revision; Corrigendum 1 on 26 October 2023, Corrigendum 2 on 21 December 2023; SCCS/1647/22; Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS): Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (NIFDC). Technical Guidelines for Application of Read-Across; NIFDC: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Cooperation on Cosmetics Regulation (ICCR). Report for the International Cooperation on Cosmetics Regulation, Integrated Strategies for Safety Assessment of Cosmetic Ingredients NGRA Best Practice. Available online: https://www.iccr-cosmetics.org/downloads/content/2025_iccr_%20integrated_strategies_for_safety_assessment_of_cosmetic_ingredients_-_ngra_best_practice.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US FDA). Roadmap to Reducing Animal Esting in Preclinical Safety Studies. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/186092/download (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Miccoli, A.; Marx-Stoelting, P.; Braeuning, A. The use of NAMs and omics data in risk assessment. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e200908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Guidance Document on the Characterisation, Validation and Reporting of Physiologically Based Kinetic (PBK) Models for Regulatory Purposes; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 331; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.W.; Diderich, R.; Kuseva, C.D.; Mekenyan, O.G. The OECD QSAR Toolbox starts its second decade. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1800, 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, K.L.; Carr, G.; Rose, J.L.; Selman, B.G. An interim internal Threshold of Toxicologic Concern (iTTC) for chemicals in consumer products, with support from an automated assessment of ToxCast™ dose response data. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Z.; Murudzwa, D.; Blum, K. Establishment of a threshold of toxicological concern for pharmaceutical intermediates based on historical repeat-dose data and its application in setting health based exposure limits. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 156, 105764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Kotaki, A.; Fukushima, A.; Kawamura, T.; Katsutani, N.; Yamada, T.; Hirose, A. Estimation of intravenous TTC (TTCiv) for Extractables and Leachables (E&Ls) by applying a modifying factor based on blood concentration predicted using an open-source PBPK model. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2025, 50, 471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, A.; Ellison, C.A.; Gregoire, S.; Hewitt, N.J. Practical application of the interim internal threshold of toxicological concern (iTTC): A case study based on clinical data. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 311, Erratum in Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 155–164.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratford, M.R.; Ramsden, C.A.; Riley, P.A. The influence of hydroquinone on tyrosinase kinetics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 4364–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratford, M.R.; Ramsden, C.A.; Riley, P.A. Mechanistic studies of the inactivation of tyrosinase by resorcinol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapór, L. Toxicity of some phenolic derivatives—In vitro studies. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2004, 10, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, T.; Scherner, C.; Röhm, K.H.; Kolbe, L. Structure-activity relationships of thiazolyl resorcinols, potent and selective inhibitors of human tyrosinase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed Modawe Alshik Edris, N.; Abdullah, J.; Kamaruzaman, S.; Sulaiman, Y. Voltammetric determination of hydroquinone, catechol, and resorcinol by using a glassy carbon electrode modified with electrochemically reduced graphene oxide-poly(Eriochrome black T) and gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumet, M.; Lazinski, L.M.; Maresca, M.; Haudecoeur, R. Tyrosinase inhibition and antimelanogenic effects of resorcinol-containing compounds. Chem. Med. Chem. 2024, 19, e202400314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, V.; Kováčová, A.; Hartmann, H. On thermodynamics of electron, proton and PCET processes of catechol, hydroquinone and resorcinol—Consequences for redox properties of polyphenolic compounds. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.L.; Dunlap, T. Formation and biological targets of quinones: Cytotoxic versus cytoprotective effects. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Hydroquinone, CAS N°: 123-31-9. SIDS Initial Profile Assessment. Available online: https://hpvchemicals.oecd.org/UI/handler.axd?id=7ca97271-99ed-4918-90e0-5c89d1ce200c (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Overview on Genetic Toxicology TGs; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 238; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jangra, S.; Gulia, H.; Singh, J.; Dang, A.S.; Giri, S.K.; Singh, G.; Priya, K.; Kumar, A. Chemical leukoderma: An insight of pathophysiology and contributing factors. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2024, 40, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, F.A. Amended final report on the safety assessment of pyrocatechol. Int. J. Toxicol. 1997, 16, 11–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.E.; Carlsen, L. Pyrocatechol contact allergy from a permanent cream dye for eyelashes and eyebrows. Contact Dermat. 1988, 18, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishack, S.; Lipner, S.R. Exogenous ochronosis associated with hydroquinone: A systematic review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Kondo, M.; Sato, K.; Umeda, M.; Kawabata, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Matsunaga, K.; Inoue, S. Rhododendrol, a depigmentation-inducing phenolic compound, exerts melanocyte cytotoxicity via a tyrosinase-dependent mechanism. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014, 27, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, K.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, A.; Tanemura, A.; Abe, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Sumikawa, Y.; Yagami, A.; Masui, Y.; et al. Rhododendrol-induced leukoderma update I: Clinical findings and treatment. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Biochemical mechanism of rhododendrol-induced leukoderma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.E.; Gisburn, M.A. Exogenous ochronosis and myxoedema from resorcinol. Br. J. Dermatol. 1961, 73, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel. Final report on the safety assessment of 2-methylresorcinol and resorcinol. J. Am. Coll. Toxicol. 1986, 5, 167–203. [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Ramos, J.; Barros-Tornay, R.; Toledo-Pastrana, T.; Ferrándiz, L.; Calleja-Hernández, M.Á.; Moreno-Ramírez, D. Effectiveness and safety of topical 15% resorcinol in the management of mild-to-moderate hidradenitis suppurativa: A cohort study. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docampo-Simón, A.; Beltrá-Picó, I.; Sánchez-Pujol, M.J.; Fuster-Ruiz-de-Apodaca, R.; Selva-Otaolaurruchi, J.; Betlloch, I.; Pascual, J.C. Topical 15% resorcinol is associated with high treatment satisfaction in patients with mild to moderate hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology 2022, 238, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinelli, E.; Brisigotti, V.; Simonetti, O.; Campanati, A.; Sapigni, C.; D’Agostino, G.M.; Giacchetti, A.; Cota, C.; Offidani, A. Efficacy and safety of topical resorcinol 15% as long-term treatment of mild-to-moderate hidradenitis suppurativa: A valid alternative to clindamycin in the panorama of antibiotic resistance. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.; Kielhorn, J.; Koppenhöfer, J.; Wibbertmann, A.; Mangelsdorf, I. Resorcinol. In Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 71; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, F.; Schira, K.; Khettabi, L.; Lombardo, L.; Mirabile, S.; Gitto, R.; Soler-Lopez, M.; Scheuermann, J.; Wolber, G.; De Luca, L. Computational methods to analyze and predict the binding mode of inhibitors targeting both human and mushroom tyrosinase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 260, 115771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. A convenient screening method to differentiate phenolic skin whitening tyrosinase inhibitors from leukoderma-inducing phenols. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2015, 80, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.A.; Socash, T.; Khamis, N.; Justik, M.W. Electrochemical investigation of the oxidation of phenolic compounds using hypervalent iodine oxidants. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 47361–47367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US FDA). Assessing the Irritation and Sensitization Potential of Transdermal and Topical Delivery Systems for ANDAs. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/assessing-irritation-and-sensitization-potential-transdermal-and-topical-delivery-systems-andas (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Skin Sensitization in Chemical Risk Assessment; Harmonization Project Document No. 5; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, C.; Grimes, P.E.; Callender, V.D.; Alexis, A.; Baldwin, H.; Elbuluk, N.; Farris, P.; Taylor, S.; Desai, S. Thiamidol: A breakthrough innovation in the treatment of hyperpigmentation. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2025, 24, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachiramon, V.; Kositkuljorn, C.; Leerunyakul, K.; Chanprapaph, K. Isobutylamido thiazolyl resorcinol for prevention of UVB-induced hyperpigmentation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrowitz, C.; Schoelermann, A.M.; Mann, T.; Kolbe, L. Effective tyrosinase inhibition by thiamidol results in significant improvement of mild to moderate melasma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1691–1698.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggenkamp, D.; Sammain, A.; Furstenau, M. Thiamidol® in moderate-to-severe melasma: 24-week randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical study. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, P.B.; Dias, J.A.F.; Cassiano, D.P.; Esposito, A.C.C.; Miot, L.D.B.; Bagatin, E.; Miot, H.A. Efficacy and safety of topical isobutylamido thiazolyl resorcinol (Thiamidol) vs. 4% hydroquinone cream for facial melasma: An evaluator-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 1881–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.; Babadjouni, A.; Mesinkovska, N. The coronation of Thiamidol: A systematic review of clinical studies investigating the topical use of Thiamidol in combating hyperpigmentation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, AB231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network of Official Cosmetics Control Laboratories (ENOCCL). Market Surveillance Study on Skin Whitening Products. Summary Report. Available online: https://www.edqm.eu/documents/52006/1874667/Executive%20Summary%20Report%20-%20Skin%20whitening%20products%20-%202024.pdf/7e918991-6c30-b1e8-17f2-4957e109b60f (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Arora, P.; Brumley, C.; Hylwa, S. Prescription ingredients in skin-lightening products found over-the-counter post-hydroquinone ban. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 431: In Vitro Skin Corrosion: Reconstructed Human Epidermis (RHE) Test Method; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 439: In Vitro Skin Irritation: Reconstructed Human Epidermis Test Method; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 432: In Vitro 3T3 NRU Phototoxicity Test; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 471: Bacterial Reverse Mutation Test; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 487: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 476: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation Test; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, R.J.; Jenkinson, S.; Brown, A.; Delaunois, A.; Dumotier, B.; Pannirselvam, M.; Rao, M.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Schmidt, F.; Sibony, A.; et al. The state of the art in secondary pharmacology and its impact on the safety of new medicines. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 525–545, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 563.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofins Discovery. SAFETYscanTM, Sample Study Report. Available online: https://cf-ecom.eurofinsdiscoveryservices.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Safety47KdMAX_Sample_Study_Report.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Willmann, S.; Höhn, K.; Edginton, A.; Sevestre, M.; Solodenko, J.; Weiss, W.; Lippert, J.; Schmitt, W. Development of a physiology-based whole-body population model for assessing the influence of individual variability on the pharmacokinetics of drugs. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2007, 34, 401–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, S.; Lippert, J.; Schmitt, W. From physicochemistry to absorption and distribution: Predictive mechanistic modelling tools. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2005, 1, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, S.; Lippert, J.; Sevestre, M.; Solodenko, J.; Fois, F.; Schmitt, W. PK-Sim®: A physiologically based pharmacokinetic whole-body model. Biosilico 2003, 1, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, K.; Coboeken, K.; Willmann, S.; Burghaus, R.; Dressman, J.B.; Lippert, J. Evolution of a detailed physiological model to simulate the gastrointestinal transit and absorption process in humans, part 1: Oral solutions. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 5324–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancik, Y.; Miller, M.A.; Jaworska, J.; Kasting, G.B. Design and performance of a spreadsheet-based model for estimating bioavailability of chemicals from dermal exposure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 428: Skin Absorption: In Vitro Method; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Diembeck, W.; Beck, H.; Benech-Kieffer, F.; Courtellemont, P.; Dupuis, J.; Lovell, W.; Paye, M.; Spengler, J.; Steiling, W. Test guidelines for in vitro assessment of dermal absorption and percutaneous penetration of cosmetic ingredients. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohlenius-Sternbeck, A.-K. Determination of the hepatocellularity number for human, dog, rabbit, rat and mouse livers from protein concentration measurements. Toxicol. In Vitro 2006, 20, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Ando, H.; Ose, A.; Kitamura, Y.; Ando, T.; Kusuhara, H.; Sugiyama, Y. Relationship between urinary excretion mechanisms of drugs and physicochemical properties. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 3294–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, T.; Rowland, M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling 2: Predicting the tissue distribution of acids, very weak bases, neutrals and zwitterions. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 1238–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Erler, S.; Kolbe, L.; Najjar, A.; Schepky, A.; Kamal, A.; Lange, D.; Rogers, T. Targeting Melanin Production: The Safety of Tyrosinase Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010097

Erler S, Kolbe L, Najjar A, Schepky A, Kamal A, Lange D, Rogers T. Targeting Melanin Production: The Safety of Tyrosinase Inhibition. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleErler, Steffen, Ludger Kolbe, Abdulkarim Najjar, Andreas Schepky, Ahmed Kamal, Daniela Lange, and Tamara Rogers. 2026. "Targeting Melanin Production: The Safety of Tyrosinase Inhibition" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010097

APA StyleErler, S., Kolbe, L., Najjar, A., Schepky, A., Kamal, A., Lange, D., & Rogers, T. (2026). Targeting Melanin Production: The Safety of Tyrosinase Inhibition. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010097