A Comparative Analysis of Absorbance- and Fluorescence-Based 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran Assay and Its Application for Evaluating Type II Photosensitization of Flavin Derivatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

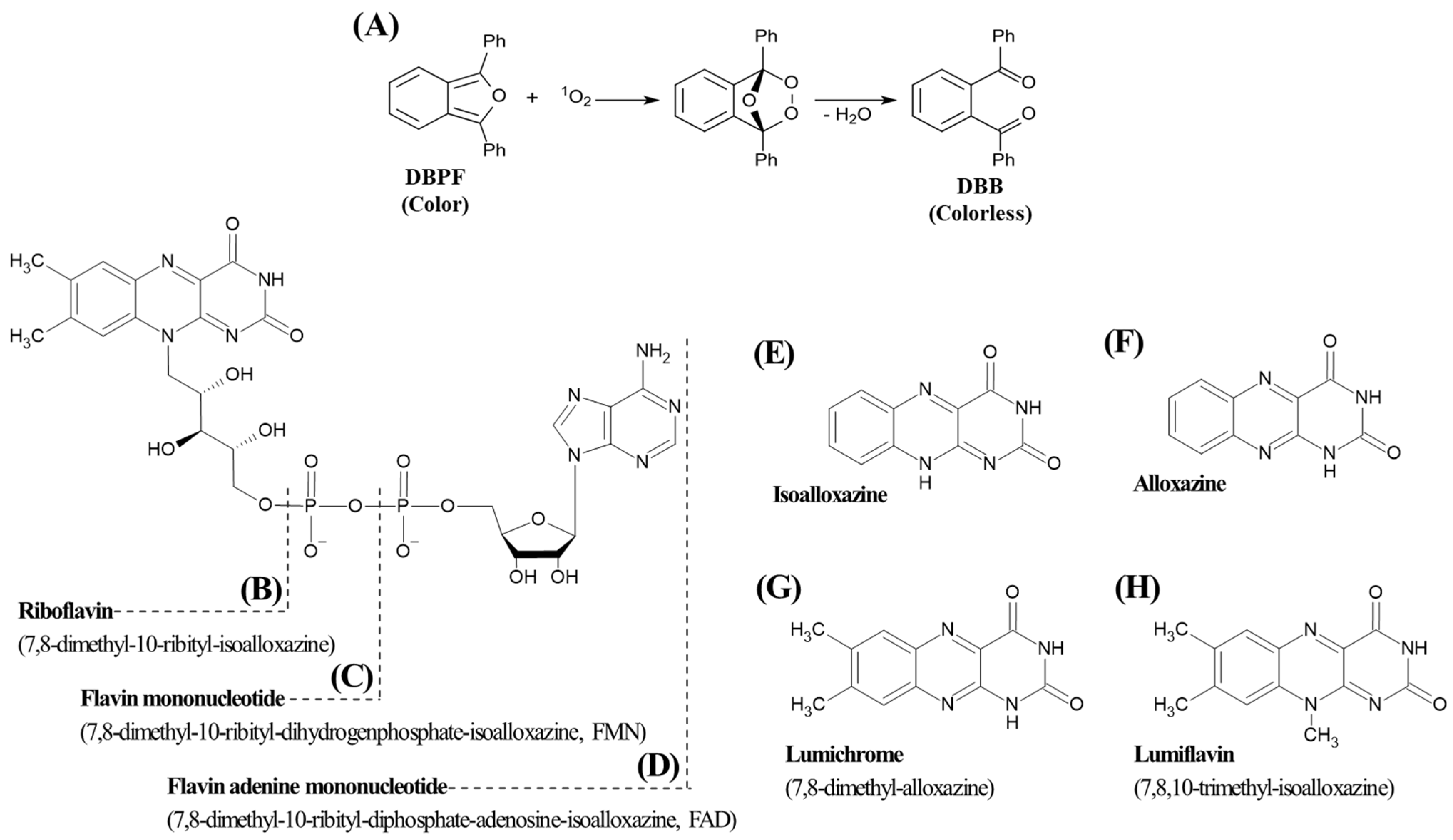

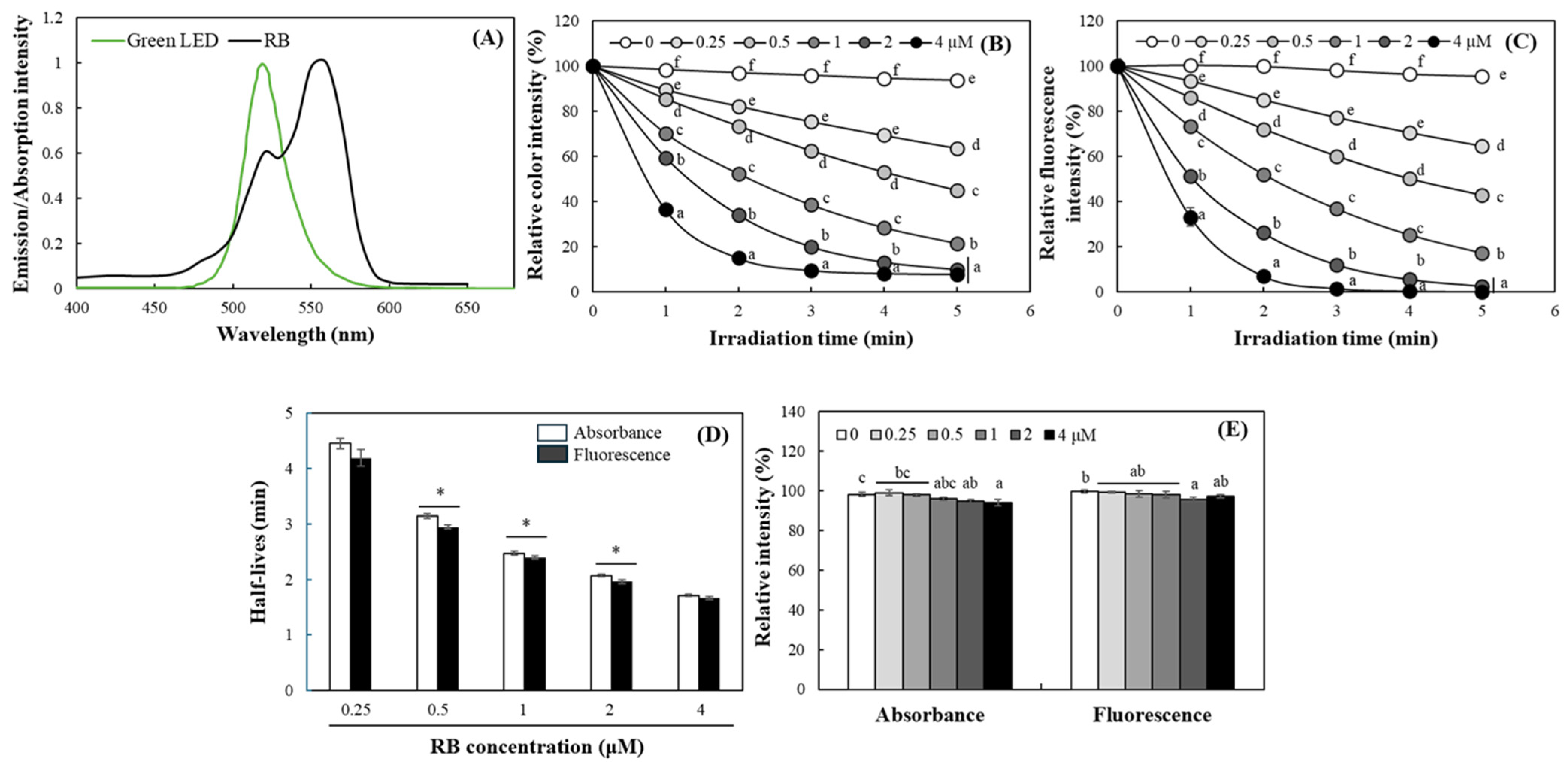

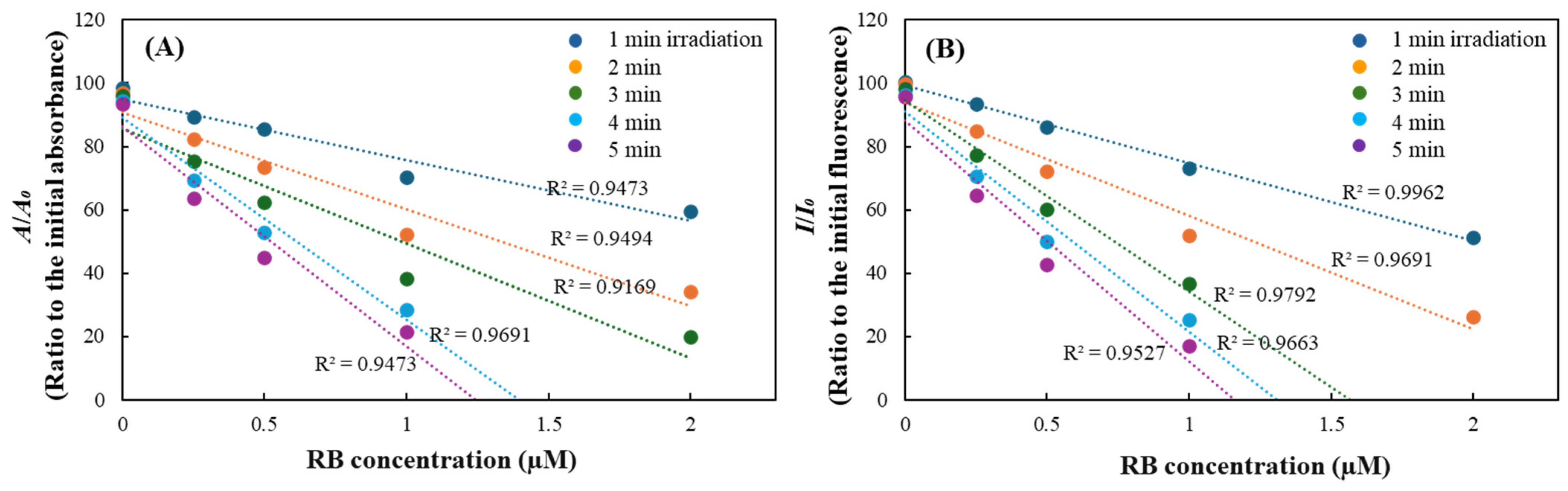

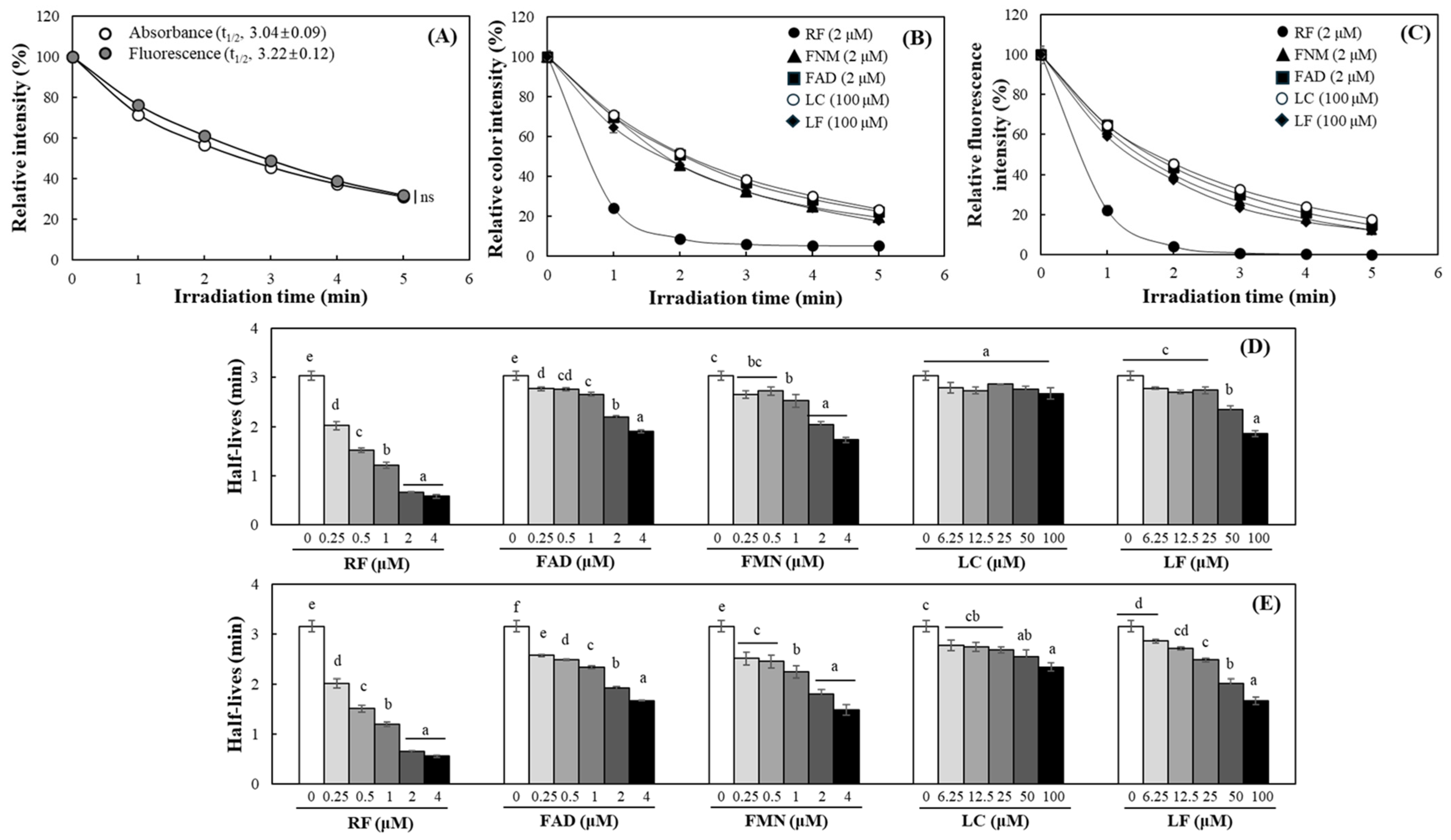

2.1. Evaluation of DPBF as a Probe for Type II Photosensitization

2.2. Evaluation of DPBF Stability Under Various Light Sources

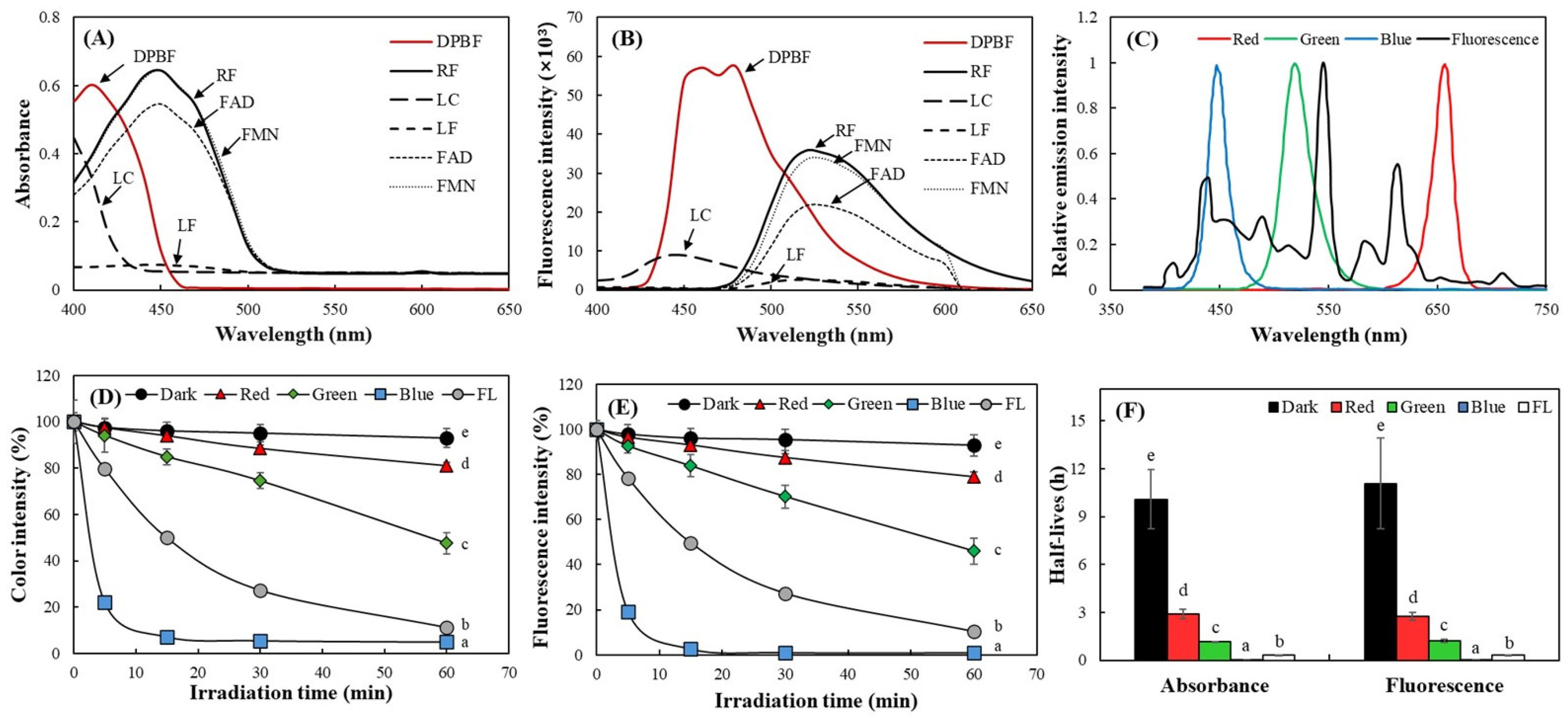

2.3. Detection of Relative Singlet Oxygen Level Produced by RF and Its Derivatives Using DPBF

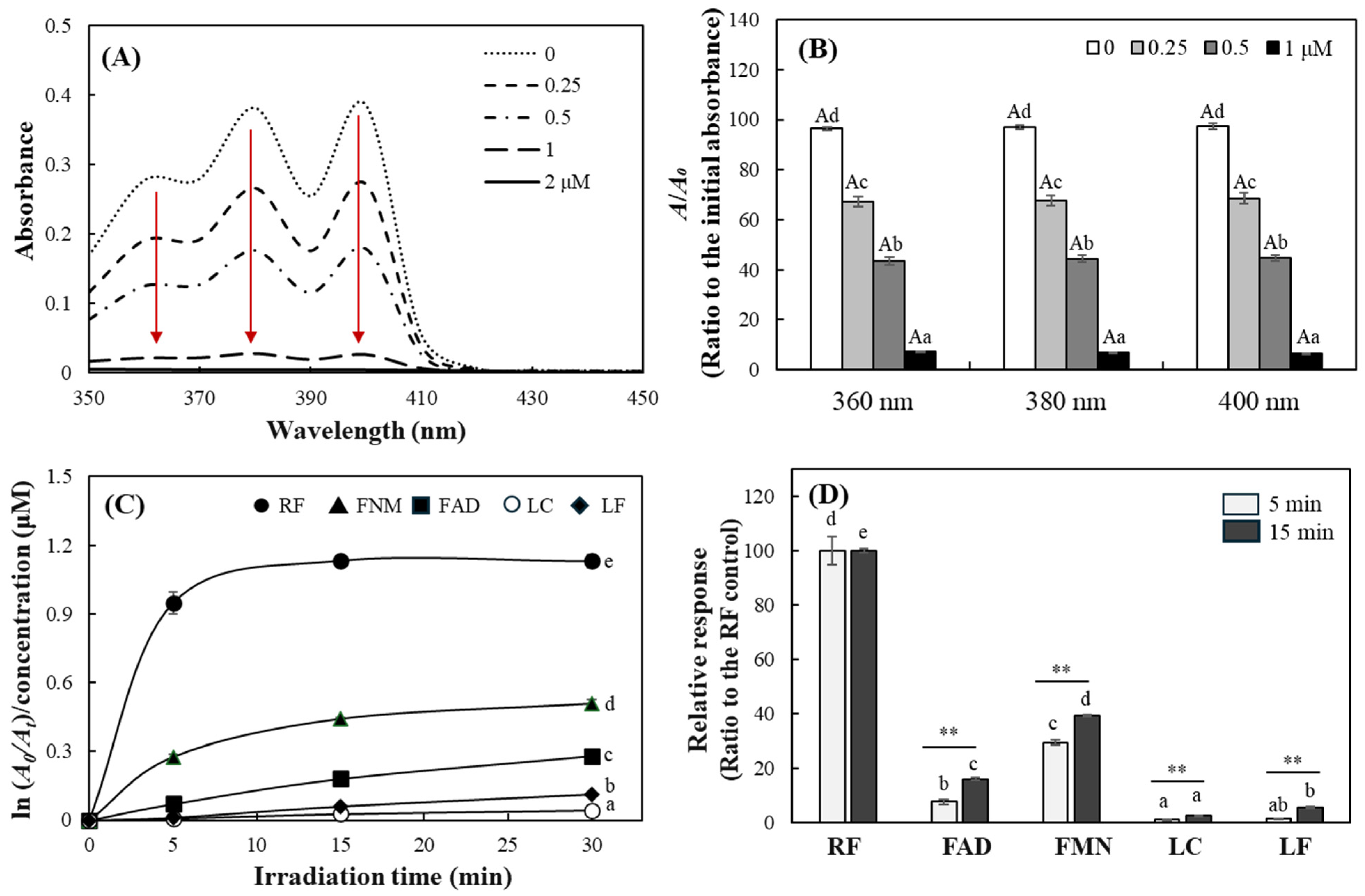

2.4. Quantitative Analysis of Photosensitizing Properties of RF and Its Derivatives

2.5. Comparison of Photosensitizing Properties of RF and Its Derivatives Under Blue LED

2.6. Comparison of the Photosensitizing Properties with ABDA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Materials

3.2. Light Irradiation System

3.3. Absorption and Fluorescence Properties of DPBF and Photosensitizers

3.4. Analysis of DPBF Photostability

3.5. Detection of Relative Levels of Singlet Oxygen Generated by Photosensitization

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kearns, D.R. Physical and chemical properties of singlet molecular oxygen. Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 395–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, R. Singlet oxygen: There is still something new under the sun, and it is better than ever. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2010, 9, 1543–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, A.; Ramasamy, E.; Ramalingam, V.; Pattabiraman, M. Supramolecular Control of Singlet Oxygen Generation. Molecules 2021, 26, 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, P.; Martinez, G.R.; Miyamoto, S.; Ronsein, G.E.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Cadet, J. Singlet molecular oxygen reactions with nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2043–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghogare, A.A.; Greer, A. Using singlet oxygen to synthesize natural products and drugs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9994–10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Lin, L.; Lin, H.; Wilson, B.C. Photosensitized singlet oxygen generation and detection: Recent advances and future perspectives in cancer photodynamic therapy. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgenträger, A.; Maisch, T.; Späth, A.; Schröder, J.A.; Bäumler, W. Singlet oxygen generation in porphyrin-doped polymeric surface coating enables antimicrobial effects on Staphylococcus aureus. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20598–20607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y. Chemical tools for the generation and detection of singlet oxygen. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4044–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takajo, T.; Kurihara, Y.; Iwase, K.; Miyake, D.; Tsuchida, K.; Anzai, K. Basic Investigations of Singlet Oxygen Detection Systems with ESR for the Measurement of Singlet Oxygen Quenching Activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entradas, T.; Waldron, S.; Volk, M. The detection sensitivity of commonly used singlet oxygen probes in aqueous environments. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 204, 111787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, M.S.; Cadet, J.; Di Mascio, P.; Ghogare, A.A.; Greer, A.; Hamblin, M.R.; Lorente, C.; Nunez, S.C.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Thomas, A.H.; et al. Type I and type II photosensitized oxidation reactions: Guidelines and mechanistic pathways. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, R.; Truscott, T.G. The reactive oxygen species singlet oxygen, hydroxy radicals, and the superoxide radical anion—Examples of their roles in biology and medicine. Oxygen 2021, 1, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diaz, M.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Use of fluorescent probes for ROS to tease apart Type I and Type II photochemical pathways in photodynamic therapy. Methods 2016, 109, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, S.; Wei, Z.; Huang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, T.C.; Huang, Z. Singlet oxygen in photodynamic therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 17, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic therapy review: Principles, photosensitizers, applications, and future directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insinska-Rak, M.; Sikorski, M. Riboflavin interactions with oxygen—A survey from the photochemical perspective. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 15280–15291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Kim, H.J.; Min, D.B. Photosensitizing effect of riboflavin, lumiflavin, and lumichrome on the generation of volatiles in soy milk. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2359–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Fasihullah, Q.; Noor, A.; Ansari, I.A.; Ali, Q.N. Photolysis of riboflavin in aqueous solution: A kinetic study. Int. J. Pharm. 2004, 280, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafaye, C.; Aumonier, S.; Torra, J.; Signor, L.; von Stetten, D.; Noirclerc-Savoye, M.; Shu, X.; Ruiz-González, R.; Gotthard, G.; Royant, A.; et al. Riboflavin-binding proteins for singlet oxygen production. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022, 21, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.C. Ultraviolet radiation-induced photodegradation and 1O2, O2-. production by riboflavin, lumichrome and lumiflavin. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 1989, 26, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maharjan, P.S.; Bhattarai, H.K. Singlet Oxygen, Photodynamic Therapy, and Mechanisms of Cancer Cell Death. J. Oncol. 2022, 25, 7211485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. Photodynamic therapy-mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, G.Ú.L.; Silva-Junior, G.J.; Brancini, G.T.P.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Wainwright, M. Photoantimicrobials in agriculture. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2022, 235, 112548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, G.; Minto, F.; Gleria, M.; Bertani, R.; Bortolus, P. Phosphazene-bound Rose Bengal: A novel photosensitizer for singlet oxygen generation. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 1991, 1, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, Ș.; Ramalho, J.P.P.; Holca, A.; Chiș, V. Photophysical Properties of 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran as a Sensitizer and Its Reaction with O2. Molecules 2025, 30, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insinska-Rak, M.; Sikorski, M.; Wolnicka-Glubisz, A. Riboflavin and its derivates as potential photosensitizers in the photodynamic treatment of skin cancers. Cells 2023, 12, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovan, A.; Sedláková, D.; Lee, O.S.; Bánó, G.; Sedlák, E. pH modulates efficiency of singlet oxygen production by flavin cofactors. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 28783–28790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.D.; Penzkoferm, A.; Hegemann, P. Quantum yield of triplet formation of riboflavin in aqueous solution and of flavin mononucleotide bound to the LOV1 domain of Phot1 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Chem. Phys. 2003, 291, 97–114, Erratum in Chem. Phys. 2003, 293, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, E.; Khmelinskii, I.; Komasa, A.; Koput, J.; Ferreira, L.F.; Herance, J.R.; Bourdelande, J.L.; Williams, S.L.; Worrall, D.R.; Insińska-Rak, M.; et al. Spectroscopy and photophysics of flavin related compounds: Riboflavin and iso-(6,7)-riboflavin. Chem. Phys. 2005, 314, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, E.; Khmelinskii, I.V.; Prukała, W.; Williams, S.L.; Patel, M.; Worrall, D.R.; Bourdelande, J.L.; Koput, J.; Sikorski, M. Spectroscopy and photophysics of lumiflavins and lumichromes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remucal, C.K.; McNeill, K. Photosensitized amino acid degradation in the presence of riboflavin and its derivatives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5230–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Song, J.; Nie, L.; Chen, X. Reactive oxygen species generating systems meeting challenges of photodynamic cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6597–6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Hong, J. Modulation of Photosensitizing Responses in Cell Culture Environments by Different Medium Components. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X. The photostability and fluorescence properties of diphenylisobenzofuran. J. Lumin. 2011, 131, 2263–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Absorbance | Fluorescence | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irradiation Time (min) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 0 | 0.00 ± 0.03 a(1) | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.00 ± 0.04 a | 0.00 ± 0.02 a | 0.00 ± 0.02 a | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | |

| RF (μM) | 0.25 | 0.17 ± 0.03 b | 0.32 ± 0.04 b | 0.45 ± 0.05 b | 0.56 ± 0.06 b | 0.65 ± 0.07 b | 0.20 ± 0.03 b | 0.35 ± 0.04 b | 0.54 ± 0.05 b | 0.70 ± 0.05 ab | 0.86 ± 0.06 ab* |

| 0.5 | 0.31 ± 0.03 bc | 0.61 ± 0.05 bc | 0.85 ± 0.05 bc | 1.02 ± 0.05 b | 1.15 ± 0.06 b | 0.35 ± 0.03 b | 0.68 ± 0.04 c | 1.04 ± 0.05 c* | 1.37 ± 0.05 bc* | 1.72 ± 0.06 bc* | |

| 1 | 0.61 ± 0.05 cd | 1.14 ± 0.07 cd | 1.49 ± 0.09 d | 1.66 ± 0.12 c | 1.68 ± 0.21 c | 0.63 ± 0.05 b | 1.34 ± 0.06 d* | 2.08 ± 0.06 d** | 2.78 ± 0.06 d** | 3.54 ± 0.07 d* | |

| 2 | 1.09 ± 0.11 e | 1.84 ± 0.19 e | 2.02 ± 0.31 e | 1.95 ± 0.54 cd | 1.76 ± 0.81 c | 1.24 ± 0.05 c*(2) | 2.70 ± 0.05 e** | 4.20 ± 0.01 e** | 5.68 ± 0.01 e** | 6.55 ± 0.02 e** | |

| 4 | 1.67 ± 0.18 f | 2.30 ± 0.03 f | 2.24 ± 1.13 e | 2.07 ± 2.26 d | 1.91 ± 0.69 c | 2.12 ± 0.22 d* | 4.64 ± 0.34 f** | 5.94 ± 0.36 f** | 6.20 ± 0.37 f** | 6.79 ± 0.35 f** | |

| FAD (μM) | 0.25 | 0.00 ± 0.01 a | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.02 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a |

| 0.5 | −0.01 ± 0.01 a | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 b | 0.05 ± 0.00 b* | 0.08 ± 0.01 b** | 0.10 ± 0.01 b** | 0.13 ± 0.01 b** | |

| 1 | −0.03 ± 0.02 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 c | 0.08 ± 0.01 c | 0.12 ± 0.01 c | 0.15 ± 0.01 c | 0.06 ± 0.01 c | 0.11 ± 0.01 c | 0.17 ± 0.02 c* | 0.22 ± 0.01 c** | 0.27 ± 0.02 c** | |

| 2 | 0.08 ± 0.04 b | 0.11 ± 0.02 d | 0.19 ± 0.02 d | 0.25 ± 0.01 d | 0.31 ± 0.02 d | 0.11 ± 0.01 d | 0.22 ± 0.01 d** | 0.34 ± 0.02 d** | 0.45 ± 0.02 d** | 0.54 ± 0.03 d** | |

| 4 | 0.17 ± 0.03 c | 0.27 ± 0.03 e | 0.41 ± 0.02 e | 0.53 ± 0.02 e | 0.62 ± 0.01 e | 0.21 ± 0.02 e | 0.42 ± 0.01 e** | 0.63 ± 0.02 e** | 0.85 ± 0.01 e** | 1.06 ± 0.02 e** | |

| FMN (μM) | 0.25 | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 0.01 ± 0.03 a | 0.02 ± 0.04 a | 0.04 ± 0.04 a | 0.05 ± 0.04 a | 0.02 ± 0.04 a | 0.03 ± 0.04 a | 0.04 ± 0.04 a | 0.05 ± 0.05 a | 0.06 ± 0.05 a |

| 0.5 | −0.02 ± 0.01 a | −0.01 ± 0.04 a | 0.00 ± 0.04 a | 0.02 ± 0.05 a | 0.03 ± 0.05 a | 0.03 ± 0.04 a | 0.05 ± 0.04 a | 0.08 ± 0.04 ab | 0.09 ± 0.05 ab | 0.12 ± 0.05 ab | |

| 1 | 0.00 ± 0.06 a | 0.06 ± 0.05 ab | 0.10 ± 0.06 a | 0.13 ± 0.07 a | 0.15 ± 0.07 a | 0.08 ± 0.04 a | 0.15 ± 0.04 a | 0.20 ± 0.04 b | 0.26 ± 0.05 b | 0.33 ± 0.06 b | |

| 2 | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.19 ± 0.05 b | 0.28 ± 0.06 b | 0.35 ± 0.07 b | 0.39 ± 0.08 b | 0.14 ± 0.04 b | 0.31 ± 0.05 b | 0.45 ± 0.05 c | 0.57 ± 0.06 c | 0.71 ± 0.07 c* | |

| 4 | 0.20 ± 0.02 c | 0.35 ± 0.06 c | 0.60 ± 0.07 c | 0.72 ± 0.06 c | 0.77 ± 0.07 c | 0.28 ± 0.07 c | 0.65 ± 0.08 c | 1.00 ± 0.09 d* | 1.32 ± 0.10 d** | 1.66 ± 0.12 d** | |

| LC (μM) | 6.25 | 0.01 ± 0.04 a | 0.03 ± 0.03 a | 0.05 ± 0.03 a | 0.06 ± 0.04 a | 0.08 ± 0.04 a | 0.03 ± 0.02 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.03 b | 0.06 ± 0.04 b | 0.08 ± 0.04 b |

| 12.5 | 0.01 ± 0.03 a | 0.05 ± 0.03 a | 0.08 ± 0.03 ab | 0.11 ± 0.04 ab | 0.11 ± 0.04 ab | 0.03 ± 0.02 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 ab | 0.06 ± 0.03 b | 0.08 ± 0.04 b | 0.10 ± 0.04 b | |

| 25 | −0.02 ± 0.01 a | −0.01 ± 0.01 a | 0.01 ± 0.02 a | 0.04 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a** | 0.05 ± 0.0 ab** | 0.09 ± 0.02 b** | 0.12 ± 0.02 b** | 0.14 ± 0.02 b** | |

| 50 | −0.09 ± 0.01 a | −0.05 ± 0.04 a | 0.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.03 ± 0.04 a | 0.06 ± 0.05 a | 0.07 ± 0.05 a** | 0.09 ± 0.04 b** | 0.16 ± 0.04 c** | 0.21 ± 0.04 c** | 0.25 ± 0.05 c** | |

| 100 | 0.00 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.04 a | 0.11 ± 0.05 b | 0.16 ± 0.06 b | 0.22 ± 0.07 b | 0.12 ± 0.02 b** | 0.19 ± 0.02 c** | 0.29 ± 0.03 d** | 0.35 ± 0.04 d** | 0.42 ± 0.05 d** | |

| LF (μM) | 6.25 | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.00 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.05 ± 0.02 b |

| 12.5 | 0.03 ± 0.02 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.12 ± 0.01 b | 0.15 ± 0.01 c | 0.03 ± 0.01 b | 0.08 ± 0.00 b | 0.09 ± 0.01 b | 0.13 ± 0.02 b | 0.15 ± 0.02 b | |

| 25 | −0.03 ± 0.02 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.08 ± 0.02 b | 0.14 ± 0.02 b | 0.19 ± 0.02 d | 0.09 ± 0.01 b | 0.14 ± 0.02 b | 0.21 ± 0.01 c | 0.29 ± 0.02 c** | 0.36 ± 0.02 c* | |

| 50 | −0.02 ± 0.07 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.22 ± 0.03 c | 0.32 ± 0.03 c | 0.41 ± 0.03 e | 0.14 ± 0.04 c | 0.31 ± 0.03 c | 0.47 ± 0.04 d | 0.62 ± 0.04 d* | 0.79 ± 0.04 d** | |

| 100 | 0.18 ± 0.03 b | 0.38 ± 0.04 c | 0.62 ± 0.03 d | 0.79 ± 0.03 d | 0.90 ± 0.03 f | 0.28 ± 0.04 d | 0.60 ± 0.05 d** | 0.94 ± 0.05 e** | 1.28 ± 0.05 e** | 1.64 ± 0.06 e | |

| Absorbance | Fluorescence | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irradiation Time (min) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Average (1) | 0.573 | 1.029 | 1.503 | 1.985 | 2.190 | 0.655 | 1.322 | 2.099 | 2.792 | 3.421 | |

| SD (2) | 0.098 | 0.290 | 0.354 | 0.300 | 0.464 | 0.099 | 0.094 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.108 | |

| RF | CV (3) (%) | 17.13 | 28.17 | 23.57 | 15.11 | 21.18 | 15.17 | 7.08 | 1.56 | 1.50 | 3.16 |

| RL (4) | n/c (5) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | n/c | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| (6) R2 = 0.992; (7) Slope = 0.419; (8) RA = 100.0 | R2 = 0.999; Slope = 0.700; RA = 100.0 | ||||||||||

| Average | 0.007 | 0.043 | 0.078 | 0.115 | 0.147 | 0.058 | 0.105 | 0.152 | 0.206 | 0.250 | |

| SD | 0.033 | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.026 | 0.033 | |

| FAD | CV (%) | 491.21 | 51.34 | 31.02 | 14.92 | 13.44 | 6.92 | 6.57 | 14.35 | 12.57 | 13.24 |

| RL | n/c | 4.15 | 5.20 | 5.78 | 6.70 | n/c | 7.98 | 7.25 | 7.37 | 7.32 | |

| R2 = 1.000; Slope = 0.035; RA = 8.394 | R2 = 1.000; Slope = 0.049; RA = 6.930 | ||||||||||

| Average | 0.025 | 0.052 | 0.098 | 0.136 | 0.159 | 0.075 | 0.137 | 0.198 | 0.253 | 0.318 | |

| SD | 0.045 | 0.050 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.009 | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.059 | 0.074 | |

| FMN | CV (%) | 183.23 | 94.38 | 57.75 | 40.83 | 36.01 | 12.59 | 18.69 | 20.09 | 23.32 | 23.13 |

| RL | n/c | 5.10 | 6.53 | 6.85 | 7.25 | n/c | 10.37 | 9.45 | 9.07 | 9.29 | |

| R2 = 0.995; Slope = 0.035; RA = 8.398 | R2 = 1.000; Slope = 0.060; RA = 8.591 | ||||||||||

| Average | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.009 | |

| SD | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| LC | CV (%) | 174.85 | 54.10 | 55.78 | 63.04 | 57.89 | 9.58 | 11.19 | 12.70 | 23.58 | 27.03 |

| RL | n/c | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.26 | n/c | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.25 | |

| R2 = 0.996; Slope = 0.001; RA = 0.324 | R2 = 0.996; Slope = 0.002; RA = 0.226 | ||||||||||

| Average | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.015 | |

| SD | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| LF | CV (%) | 161.57 | 55.76 | 30.02 | 23.78 | 20.60 | 10.68 | 4.45 | 14.07 | 10.41 | 12.17 |

| RL | n/c | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.42 | n/c | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.43 | |

| R2 = 0.999; Slope = 0.002; RA = 0.445 | R2 = 0.999; Slope = 0.003; RA = 0.417 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, M.; Hong, J. A Comparative Analysis of Absorbance- and Fluorescence-Based 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran Assay and Its Application for Evaluating Type II Photosensitization of Flavin Derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010066

Kim M, Hong J. A Comparative Analysis of Absorbance- and Fluorescence-Based 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran Assay and Its Application for Evaluating Type II Photosensitization of Flavin Derivatives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Minkyoung, and Jungil Hong. 2026. "A Comparative Analysis of Absorbance- and Fluorescence-Based 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran Assay and Its Application for Evaluating Type II Photosensitization of Flavin Derivatives" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010066

APA StyleKim, M., & Hong, J. (2026). A Comparative Analysis of Absorbance- and Fluorescence-Based 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran Assay and Its Application for Evaluating Type II Photosensitization of Flavin Derivatives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010066

_Kim.png)