In Vivo Target Engagement Assessment of Nintedanib in a Double-Hit Bleomycin Lung Fibrosis Rat Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Kinase Cell-Free Assay

2.2. Therapeutic Effects of Nintedanib on BLM-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis

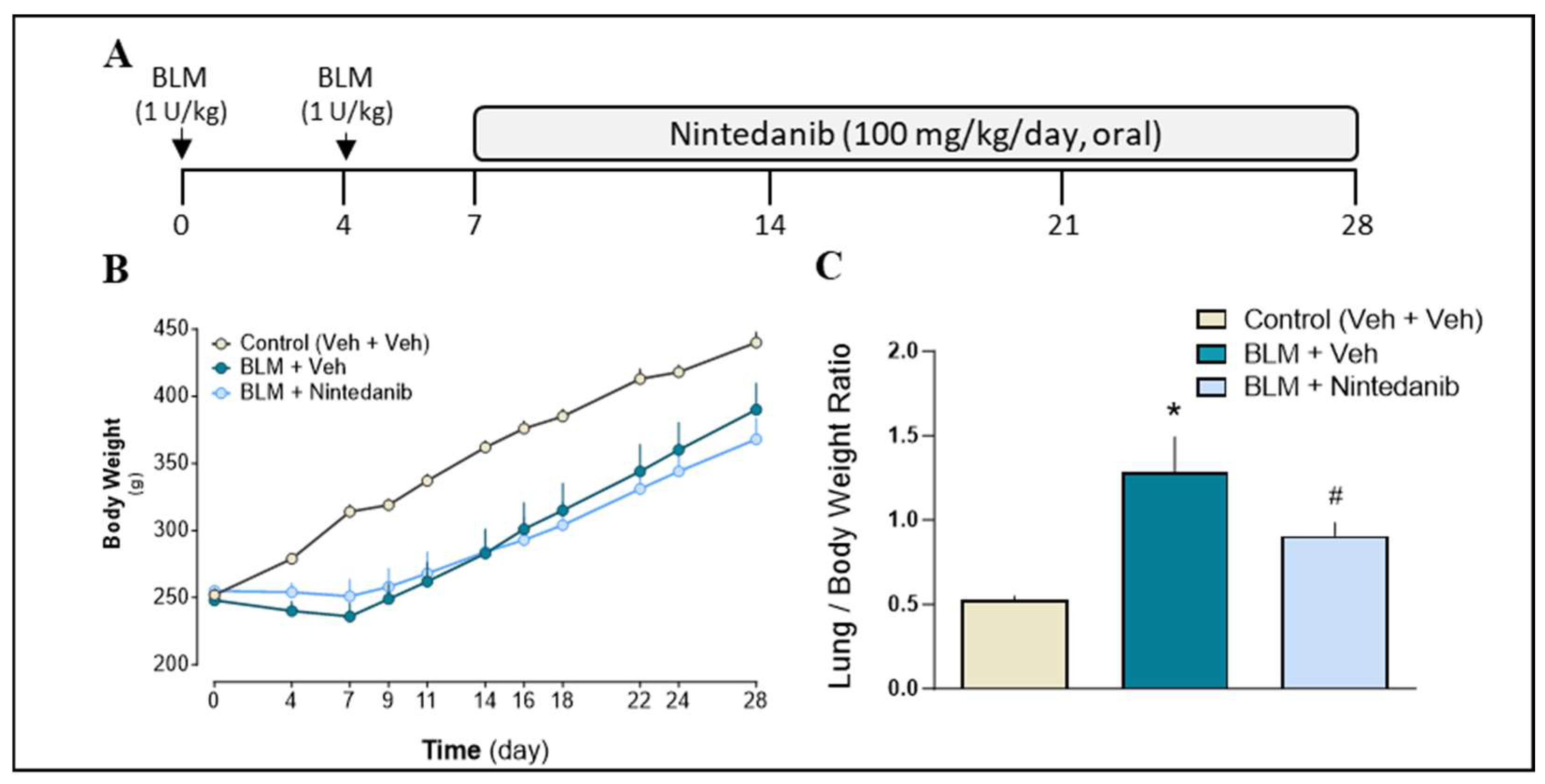

2.2.1. Animals General Health Condition and Body Weight

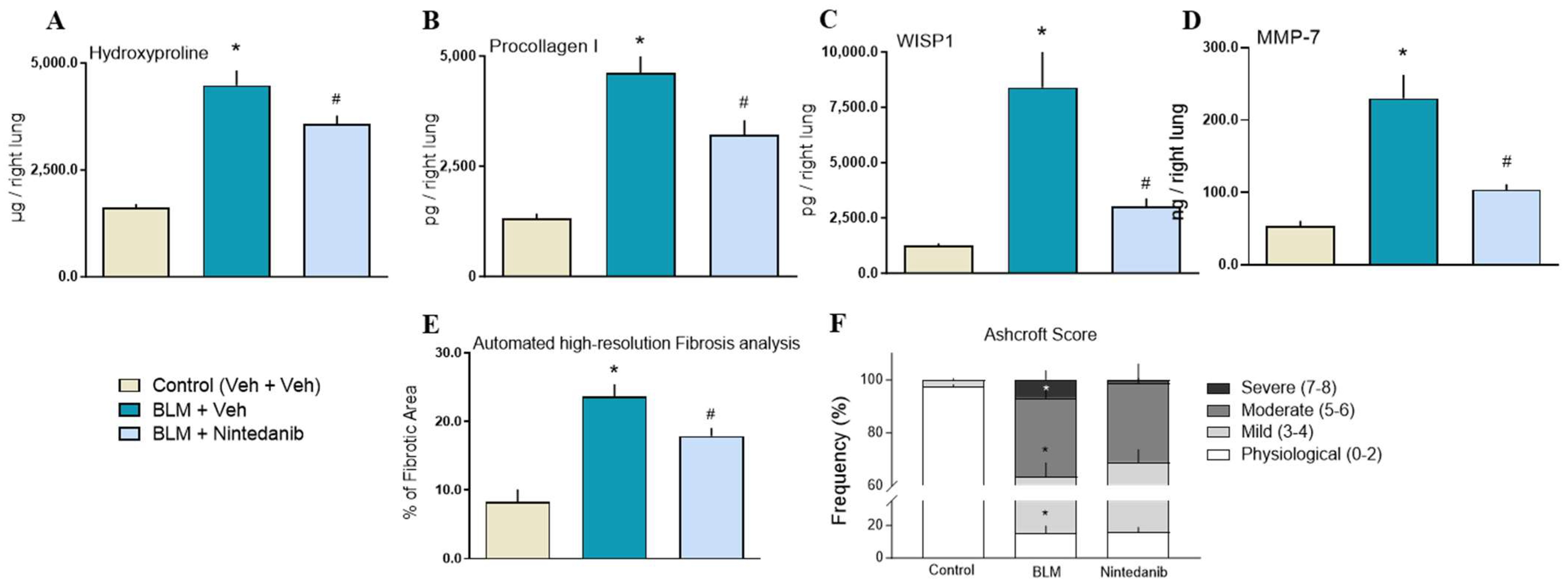

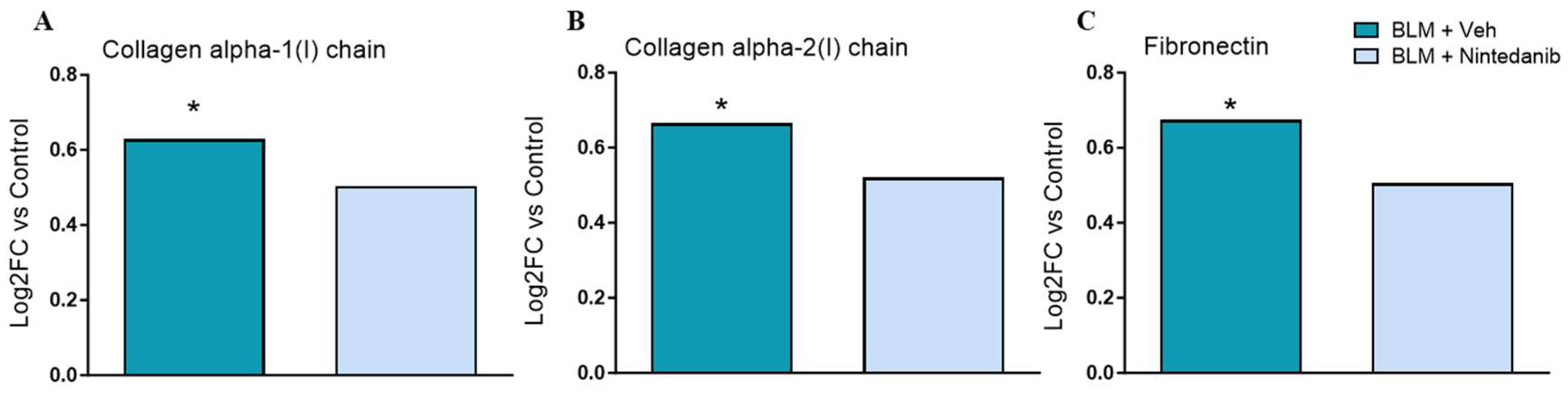

2.2.2. Effect of Nintedanib on Markers of Fibrosis

2.2.3. Histopathological Analysis

2.2.4. Effect of Nintedanib on Presumptive Targeted Growth Factors in Lung Homogenate Supernatant and Plasma

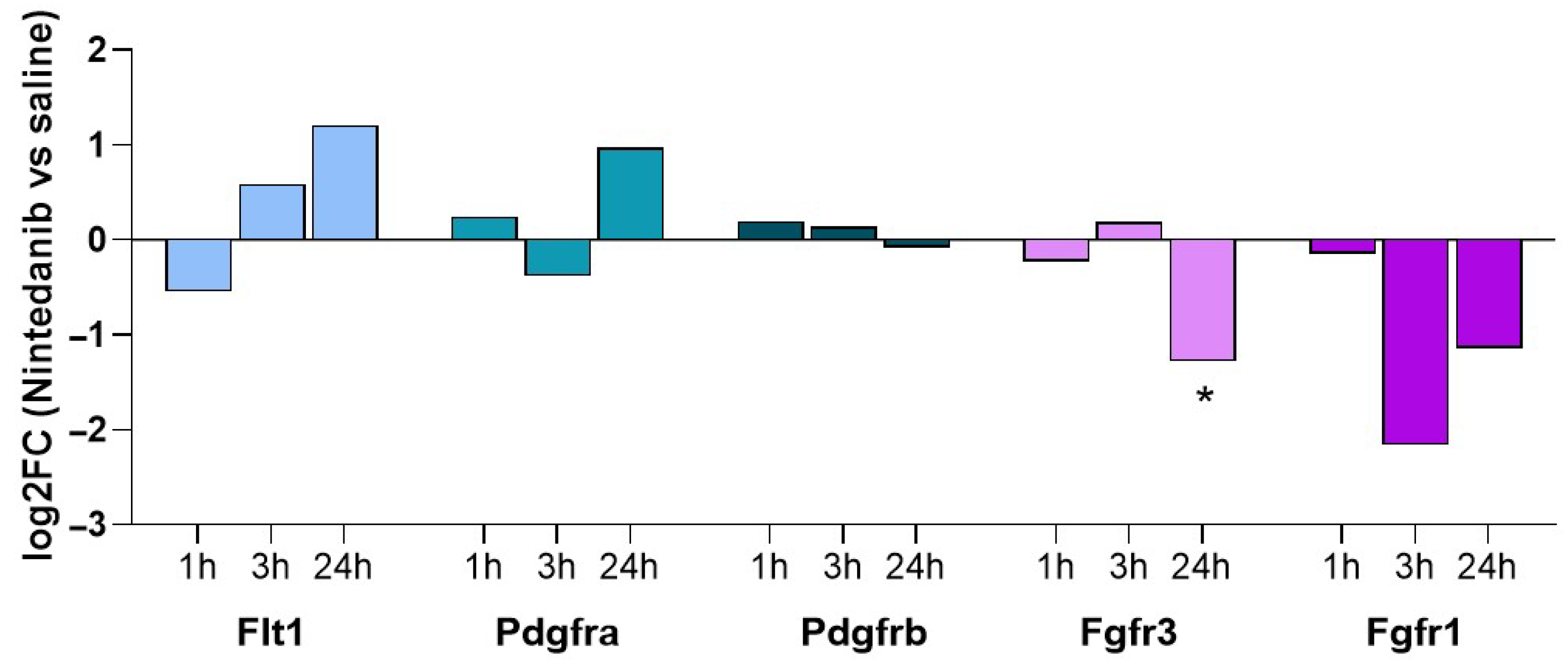

2.3. Lung Tissue Phosphoproteomic Assessment in Nintedanib Naïve Animals

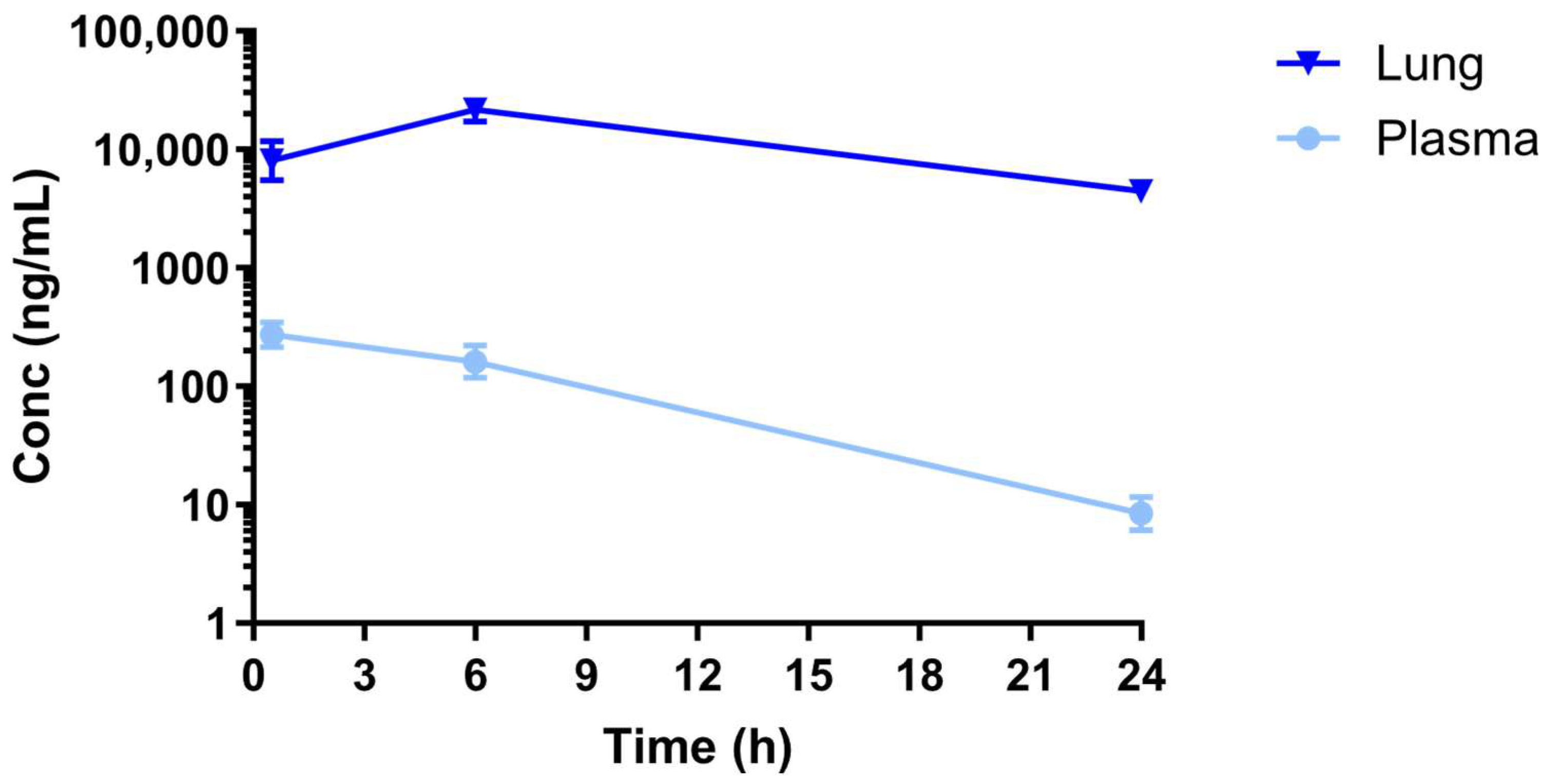

2.4. Assessment of Nintedanib Lung and Plasma Exposure

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Kinase Cell-Free Assay

4.2. Animals and BLM-Induced Lung Fibrosis Model

4.3. Histopathology Assessment

4.4. Markers Analysis in Lung Homogenate and Plasma

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.5. Lung Sample Preparation and nLC-HRMS/MS Conditions for Proteome Analysis

4.6. Assessment of Nintedanib Plasma and Lung Levels

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spagnolo, P.; Guler, S.A.; Chaudhuri, N.; Udwadia, Z.; Sesé, L.; Kaul, B.; Enghelmayer, J.I.; Valenzuela, C.; Malhotra, A.; Ryerson, C.J.; et al. Global Epidemiology and Burden of Interstitial Lung Disease. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podolanczuk, A.J.; Thomson, C.C.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Martinez, F.J.; Kolb, M.; Raghu, G. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: State of the Art for 2023. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Kropski, J.A.; Jones, M.G.; Lee, J.S.; Rossi, G.; Karampitsakos, T.; Maher, T.M.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Ryerson, C.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Disease Mechanisms and Drug Development. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 222, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poletti, V.; Ravaglia, C.; Tomassetti, S. Pirfenidone for the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2014, 8, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Bonella, F. The Management of Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.-F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-Based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-de la Mora, D.A.; Sanchez-Roque, C.; Montoya-Buelna, M.; Sanchez-Enriquez, S.; Lucano-Landeros, S.; Macias-Barragan, J.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. Role and New Insights of Pirfenidone in Fibrotic Diseases. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 12, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwanpura, S.M.; Thomas, B.J.; Bardin, P.G. Pirfenidone: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Applications in Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, R.; Kang, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Tian, J. Pirfenidone Controls the Feedback Loop of the AT1R/P38 MAPK/Renin-Angiotensin System Axis by Regulating Liver X Receptor-α in Myocardial Infarction-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Huang, X.; Ruan, Z.; Dai, Y. Pirfenidone Alleviates Pulmonary Fibrosis in Vitro and in Vivo through Regulating Wnt/GSK-3β/β-Catenin and TGF-Β1/Smad2/3 Signaling Pathways. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurahara, L.H.; Hiraishi, K.; Hu, Y.; Koga, K.; Onitsuka, M.; Doi, M.; Aoyagi, K.; Takedatsu, H.; Kojima, D.; Fujihara, Y.; et al. Activation of Myofibroblast TRPA1 by Steroids and Pirfenidone Ameliorates Fibrosis in Experimental Crohn’s Disease. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 5, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, H.V.; Maher, T.M. Nintedanib in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Drugs Today 2015, 51, 0345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollin, L.; Togbe, D.; Ryffel, B. Effects of Nintedanib in an Animal Model of Liver Fibrosis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3867198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Qi, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Xu, L.; Liu, N.; Zhuang, S. Nintedanib, a Triple Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, Attenuates Renal Fibrosis in Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollin, L.; Wex, E.; Pautsch, A.; Schnapp, G.; Hostettler, K.E.; Stowasser, S.; Kolb, M. Mode of Action of Nintedanib in the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Inomata, M.; Nishioka, Y. Nintedanib: Evidence for Its Therapeutic Potential in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Core Evid. 2015, 89, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, E.; Saladino, G.; Morando, M.A.; Martinez-Torrecuadrada, J.; Lelli, M.; Sutto, L.; D’Amelio, N.; Gervasio, F.L. An Allosteric Cross-Talk Between the Activation Loop and the ATP Binding Site Regulates the Activation of Src Kinase. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, S.; Schmid, U.; Freiwald, M.; Marzin, K.; Lotz, R.; Ebner, T.; Stopfer, P.; Dallinger, C. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Nintedanib. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinger, C.; Trommeshauser, D.; Marzin, K.; Liesener, A.; Kaiser, R.; Stopfer, P. Pharmacokinetic Properties of Nintedanib in Healthy Volunteers and Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 56, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distler, O.; Highland, K.B.; Gahlemann, M.; Azuma, A.; Fischer, A.; Mayes, M.D.; Raghu, G.; Sauter, W.; Girard, M.; Alves, M.; et al. SENSCIS Trial Investigators. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, E.S.; Salama, A.A.A.; El-Shafie, M.F.; Arafa, H.M.M.; Abdelsalam, R.M.; Khattab, M. The Anti-Fibrotic and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Bone Marrow–Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Nintedanib in Bleomycin-Induced Lung Fibrosis in Rats. Inflammation 2020, 43, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Tang, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Sun, D.; Sun, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, B.; et al. Discovery of a Novel DDRs Kinase Inhibitor XBLJ-13 for the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togami, K.; Ogasawara, A.; Irie, S.; Iwata, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tada, H.; Chono, S. Improvement of the Pharmacokinetics and Antifibrotic Effects of Nintedanib by Intrapulmonary Administration of a Nintedanib–Hydroxypropyl-γ-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex in Mice with Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2022, 172, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonatti, M.; Pitozzi, V.; Caruso, P.; Pontis, S.; Pittelli, M.G.; Frati, C.; Mangiaracina, C.; Lagrasta, C.A.M.; Quaini, F.; Cantarella, S.; et al. Time-course transcriptome analysis of a double challenge bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis rat model uncovers ECM homoeostasis-related translationally relevant genes. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Y.; Luo, R.; Fan, Z.; Dai, W.; Wei, S.; Lin, C. A novel mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis: Twice-repeated oropharyngeal bleomycin administration mimicking human pathology. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2025, 103, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchi, E.; Pitozzi, V.; Pontis, S.; Caruso, P.L.; Beghi, S.; Caputi, M.; Trevisani, M. Ruscitti, Investigation of Aberrant Basaloid Cells in a Rat Model of Lung Fibrosis. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, M.; Amit, I.; Yarden, Y. Regulation of MAPKs by Growth Factors and Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2007, 1773, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Receptor (VEGFR) Signaling in Angiogenesis: A Crucial Target for Anti- and Pro-Angiogenic Therapies. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Nawaz, M.I. Molecular Mechanism of VEGF and Its Role in Pathological Angiogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 123, 1938–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumegowda, C.; Farkas, L.; Kolb, M. Angiogenesis in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2012, 142, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, H.; Matsui, Y.; Hatanaka, K.; Hosono, K.; Ito, Y. VEGFR1-Tyrosine Kinase Signaling in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Inflamm. Regen. 2021, 41, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, Y.; Tuder, R.M.; Taraseviciene-Stewart, L.; Le Cras, T.D.; Abman, S.; Hirth, P.K.; Waltenberger, J.; Voelkel, N.F. Inhibition of VEGF Receptors Causes Lung Cell Apoptosis and Emphysema. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.R.; Perkins, G.D.; Fujisawa, T.; Pettigrew, K.A.; Gao, F.; Ahmed, A.; Thickett, D.R. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Promotes Physical Wound Repair and Is Anti-Apoptotic in Primary Distal Lung Epithelial and A549 Cells. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 2164–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, A.M.; Bouchier-Hayes, D.J.; Harmey, J.H. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Role in Non-Endothelial Cells: Autocrine Signalling by VEGF. In Madame Curie Bioscience Database; Landes Bioscience: Georgetown, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L.A.; Habiel, D.M.; Hohmann, M.; Camelo, A.; Shang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Coelho, A.L.; Peng, X.; Gulati, M.; Crestani, B.; et al. Antifibrotic Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Pulmonary Fibrosis. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e92192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, J.; Shulgina, L.; Sexton, D.; Atkins, C.; Wilson, A. Plasma Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Concentration and Alveolar Nitric Oxide as Potential Predictors of Disease Progression and Mortality in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S.L.; Flower, V.A.; Pauling, J.D.; Millar, A.B. VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S.L.; Blythe, T.; Jarrett, C.; Ourradi, K.; Shelley-Fraser, G.; Day, M.J.; Qiu, Y.; Harper, S.; Maher, T.M.; Oltean, S.; et al. Differential Expression of VEGF-A xxx Isoforms Is Critical for Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Miyazaki, E.; Ito, T.; Hiroshige, S.; Nureki, S.; Ueno, T.; Takenaka, R.; Fukami, T.; Kumamoto, T. Significance of Serum Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Level in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung 2010, 188, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simler, N.R. Angiogenic Cytokines in Patients with Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia. Thorax 2004, 59, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malli, F.; Koutsokera, A.; Paraskeva, E.; Zakynthinos, E.; Papagianni, M.; Makris, D.; Tsilioni, I.; Molyvdas, P.A.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Daniil, Z. Endothelial Progenitor Cells in the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Evolving Concept. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, N.; Kuwano, K.; Yamada, M.; Hagimoto, N.; Hiasa, K.; Egashira, K.; Nakashima, N.; Maeyama, T.; Yoshimi, M.; Nakanishi, Y. Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Therapy Attenuates Lung Injury and Fibrosis in Mice. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockmann, C.; Kerdiles, Y.; Nomaksteinsky, M.; Weidemann, A.; Takeda, N.; Doedens, A.; Torres-Collado, A.X.; Iruela-Arispe, L.; Nizet, V.; Johnson, R.S. Loss of Myeloid Cell-Derived Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Accelerates Fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4329–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, S.; Sato, E.; Haniuda, M.; Numanami, H.; Nagai, S.; Izumi, T. Decreased Level of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid of Normal Smokers and Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, B.; Luo, S. Identifying the Link between Serum VEGF and KL-6 Concentrations: A Correlation Analysis for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Interstitial Lung Disease Progression. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1282757, Correction in Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1424573, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1424573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, S.-Y.; Liu, Y.-Q. Inhibition of LPA-LPAR1 and VEGF-VEGFR2 Signaling in IPF Treatment. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 2679–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-Z.; Liang, L.-M.; Cheng, P.-P.; Xiong, L.; Wang, M.; Song, L.-J.; Yu, F.; He, X.-L.; Xiong, L.; Wang, X.-R.; et al. VEGF/Src Signaling Mediated Pleural Barrier Damage and Increased Permeability Contributes to Subpleural Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2021, 320, L990–L1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biener, L.; Kruse, J.; Tuleta, I.; Pizarro, C.; Kreuter, M.; Birring, S.S.; Nickenig, G.; Skowasch, D. Association of Proangiogenic and Profibrotic Serum Markers with Lung Function and Quality of Life in Sarcoidosis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.S.; Schupp, J.C.; Poli, S.; Ayaub, E.A.; Neumark, N.; Ahangari, F.; Chu, S.G.; Raby, B.A.; DeIuliis, G.; Januszyk, M.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Ectopic and Aberrant Lung-Resident Cell Populations in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermann, A.C.; Gutierrez, A.J.; Bui, L.T.; Yahn, S.L.; Winters, N.I.; Calvi, C.L.; Peter, L.; Chung, M.-I.; Taylor, C.J.; Jetter, C.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Profibrotic Roles of Distinct Epithelial and Mesenchymal Lineages in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePrimo, S.; Bello, C.L.; Smeraglia, J.; Baum, C.M.; Spinella, D.; Rini, B.I.; Michaelson, M.D.; Motzer, R.J. Circulating protein biomarkers of pharmacodynamic activity of sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Modulation of VEGF and VEGF-related proteins. J. Transl. Med. 2007, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jeraj, R.; Vanderhoek, M.; Perlman, S.; Kolesar, J.; Harrison, M.; Simoncic, U.; Eickhoff, J.; Carmichael, L.; Chao, B.; et al. Pharmacodynamic Study Using FLT PET/CT in Patients with Renal Cell Cancer and Other Solid Malignancies Treated with Sunitinib Malate Free. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 7634–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drevs, J.; Zirrgiebel, U.; Schmidt-Gersbach, C.I.M.; Mross, K.; Medinger, M.; Lee, L.; Pinheiro, J.; Wood, J.; Thomas, A.L.; Unger, C.; et al. Soluble markers for the assessment of biological activity with PTK787/ZK 222584 (PTK/ZK), a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer from two phase I trials. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, M.; Gordon, E.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac Gabhann, F.; Popel, A.S. Model of competitive binding of vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor to VEGF receptors on endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H153–H164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, M.; Pitozzi, V.; Caruso, P.; Pontis, S.; Pittelli, M.G.; Frati, C.; Madeddu, D.; Quaini, F.; Lagrasta, C.A.M.; Minato, I.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals lipid metabolism and macrophage involvement associated with nintedanib treatment in a rat bleomycin model. Br. J. Pharmacol 2026, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Gu, Q.; Sims, M.; Gu, W.; Pfeffer, L.M.; Yue, J. KLF4 Promotes Angiogenesis by Activating VEGF Signaling in Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Rispoli, R.; Patient, R.; Ciau-Uitz, A.; Porcher, C. Etv6 activates vegfa expression through positive and negative transcriptional regulatory networks in Xenopus embryos. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisani, M.; Caruso, P.; Pitozzi, V.; Pontis, S.; Pittelli, M.G.; Bonatti, M.; Villetti, G.; Civelli, M. Anti-Fibrotic Effect and In Vivo Target Engagement of Nintedanib Administered by Oral Gavage or by a Medicated Diet in a Bleomycin Lung Fibrosis Model in the Rat. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.D.; Gebhart, G.F.; Gonder, J.C.; Keeling, M.E.; Kohn, D.F. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 7th ed; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; Volume 38, Number 1, 125p, ISBN 0-309-05377-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, T.; Simpson, J.M.; Timbrell, V. Simple Method of Estimating. Severity of Pulmonary Fibrosis on a Numerical Scale. J. Clin. Pathol. 1988, 41, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, R.-H.; Gitter, W.; Eddine El Mokhtari, N.; Mathiak, M.; Both, M.; Bolte, H.; Freitag-Wolf, S.; Bewig, B. Standardized Quantification of Pulmonary Fibrosis in Histological Samples. Biotechniques 2008, 44, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanetti, F.; Ragionieri, L.; Ciccimarra, R.; Ruscitti, F.; Pompilio, D.; Gazza, F.; Villetti, G.; Cacchioli, A.; Stellari, F.F. Modeling Pulmonary Fibrosis through Bleomycin Delivered by Osmotic Minipump: A New Histomorphometric Method of Evaluation. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2020, 318, L376–L385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.J.; Karayel, O.; James, D.E.; Mann, M. High-Throughput and High-Sensitivity Phosphoproteomics with the EasyPhos Platform. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 1897–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Kinase | Nintedanib Concentrations (nM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1000 | 5000 | |

| FGFR1 | 49% | 3.9% | 0.1% |

| FGFR2 | 58% | 16% | 3.8% |

| FGFR3 | 64% | 9.5% | 1.3% |

| FGFR4 | 98% | 55% | 17% |

| PDGFRA | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| PDGFRB | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| VEGFR1 (FLT1) | 1.6% | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| VEGFR2 (KDR) | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| VEGFR2 (FLT4) | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pitozzi, V.; Caruso, P.L.; Pontis, S.; Pioselli, B.; Ruscitti, F.; Pittelli, M.G.; Lagrasta, C.A.M.; Quaini, F.; Nogara, A.M.; Aquino, G.; et al. In Vivo Target Engagement Assessment of Nintedanib in a Double-Hit Bleomycin Lung Fibrosis Rat Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010064

Pitozzi V, Caruso PL, Pontis S, Pioselli B, Ruscitti F, Pittelli MG, Lagrasta CAM, Quaini F, Nogara AM, Aquino G, et al. In Vivo Target Engagement Assessment of Nintedanib in a Double-Hit Bleomycin Lung Fibrosis Rat Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010064

Chicago/Turabian StylePitozzi, Vanessa, Paola Lorenza Caruso, Silvia Pontis, Barbara Pioselli, Francesca Ruscitti, Maria Gloria Pittelli, Costanza A. M. Lagrasta, Federico Quaini, Antonella Maria Nogara, Giancarlo Aquino, and et al. 2026. "In Vivo Target Engagement Assessment of Nintedanib in a Double-Hit Bleomycin Lung Fibrosis Rat Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010064

APA StylePitozzi, V., Caruso, P. L., Pontis, S., Pioselli, B., Ruscitti, F., Pittelli, M. G., Lagrasta, C. A. M., Quaini, F., Nogara, A. M., Aquino, G., Volta, R., Faietti, M. L., Bonatti, M., Spagnolo, P., & Trevisani, M. (2026). In Vivo Target Engagement Assessment of Nintedanib in a Double-Hit Bleomycin Lung Fibrosis Rat Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010064