Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Facilitates Breast Cancer Metas-Tasis via Immunosuppressive Reprogramming of Neutrophils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

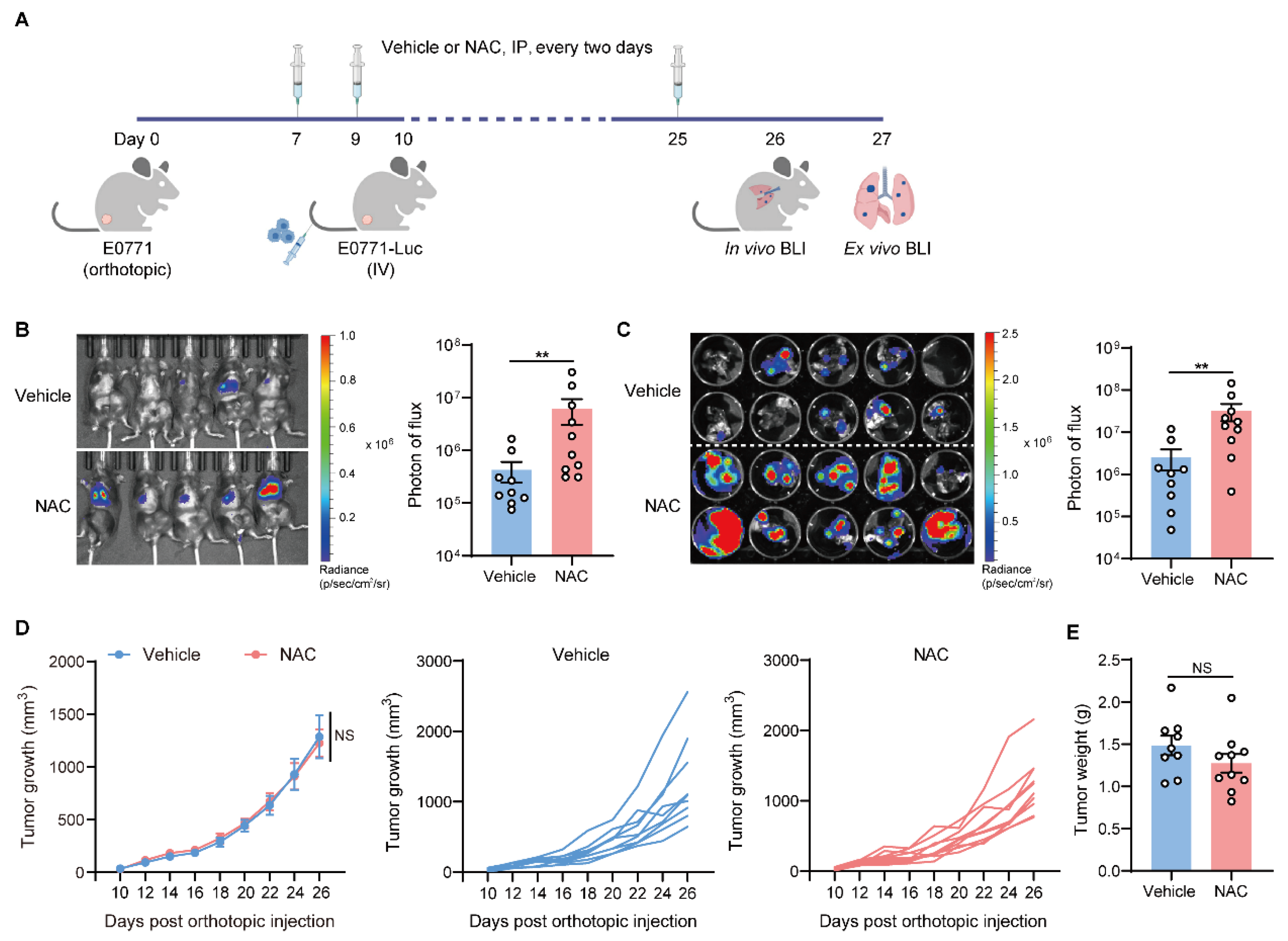

2.1. Antioxidant NAC Facilitates Lung Metastasis of Breast Cancer

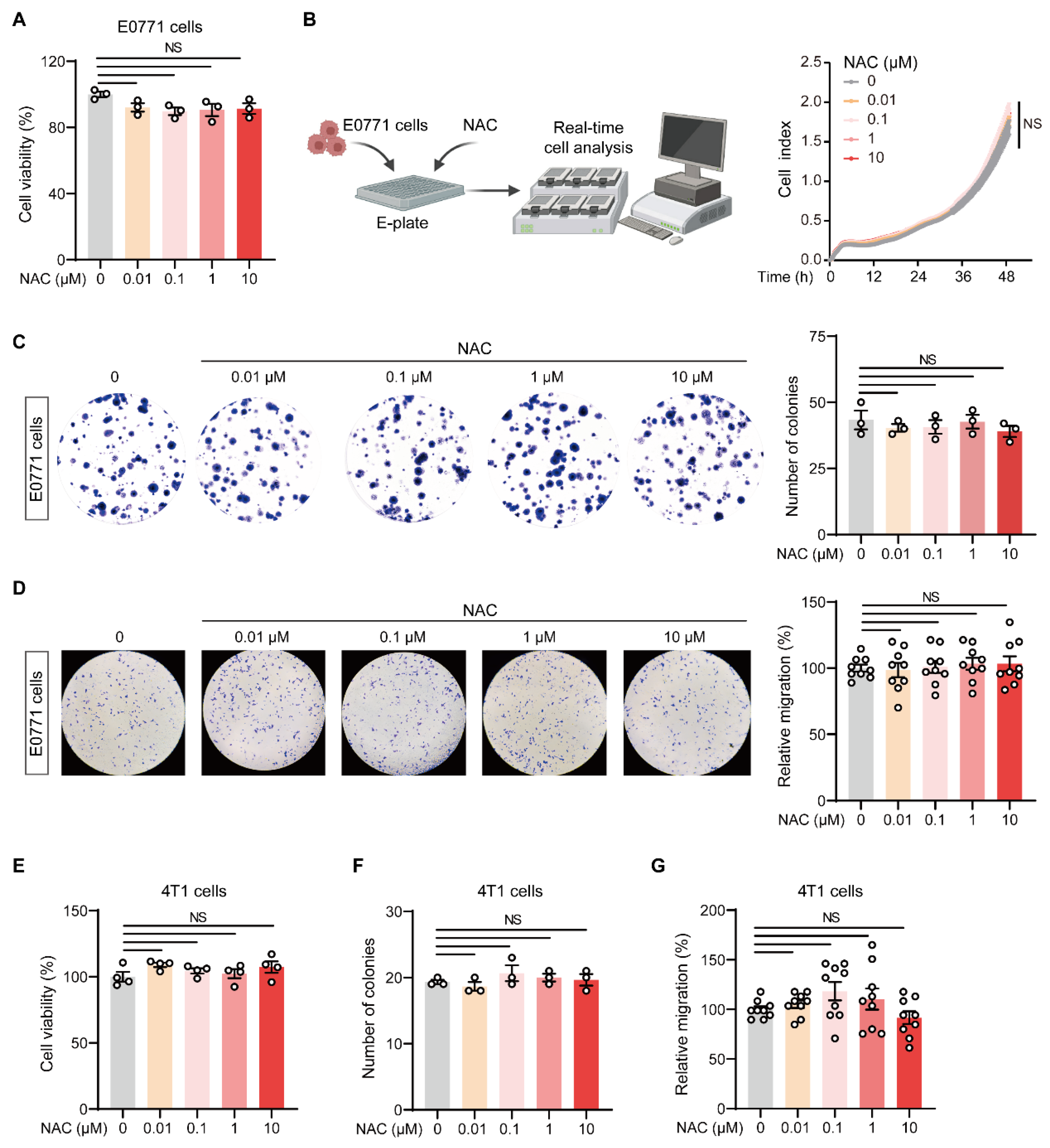

2.2. NAC Does Not Affect the Malignant Behavior of Breast Tumor Cells In Vitro

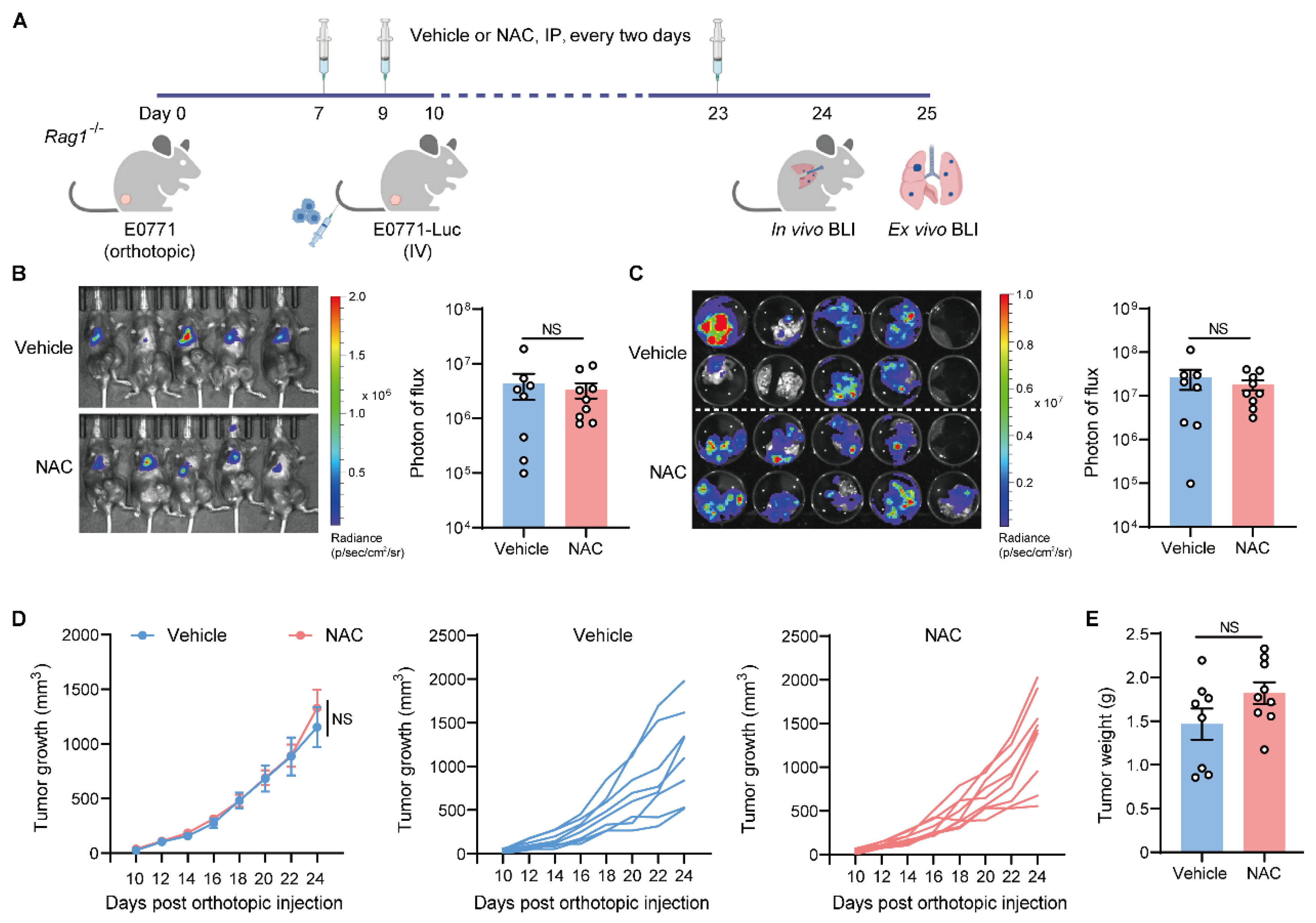

2.3. The Metastasis-Promoting Effect of NAC Is Abrogated in Immunodeficient Mice

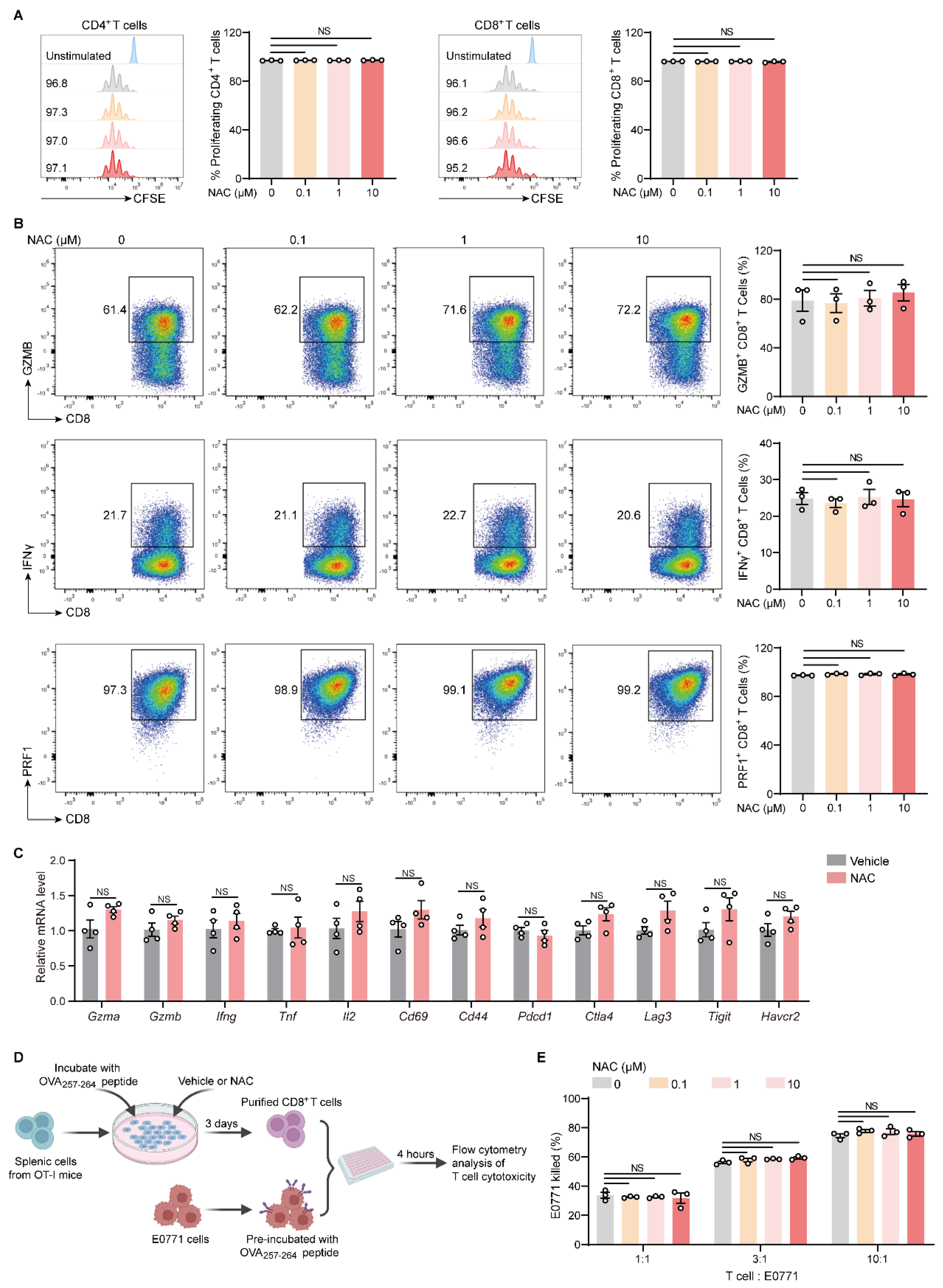

2.4. NAC Does Not Affect the Proliferation and Effector Function of T Cells In Vitro

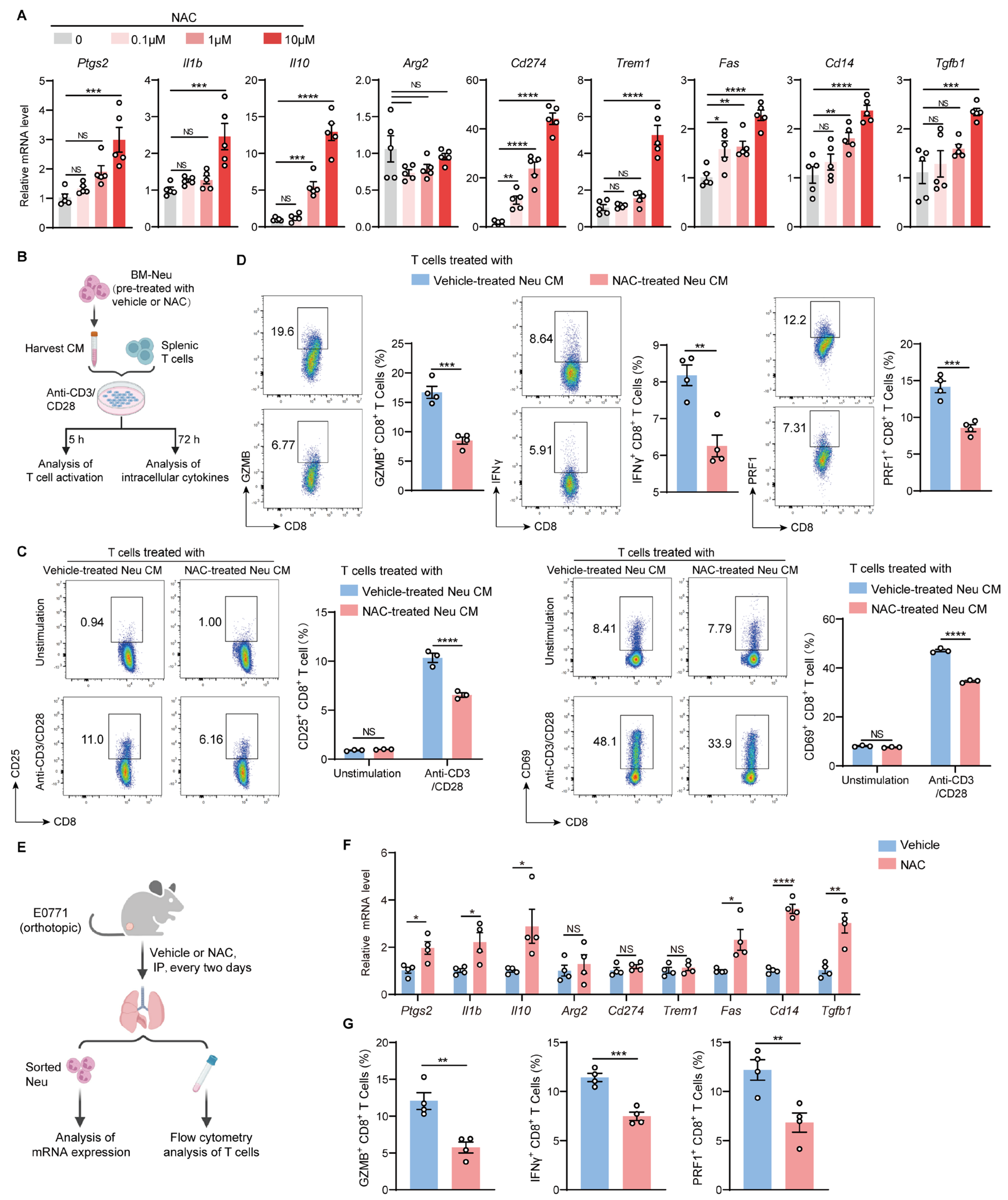

2.5. NAC Endows Neutrophils with Immunosuppressive Capacities Which Dampen the Activation and Function of T Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Generation of Luciferase-Labeled Tumor Cells

4.4. Breast Cancer Metastasis Models

4.5. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.6. Colony Formation Assay

4.7. Transwell Migration Assay

4.8. Lung Tissue Dissociation

4.9. Primary Cell Isolation

4.10. Flow Cytometry

4.11. T Cell Function Analysis

4.12. In Vitro T Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

4.13. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.14. Illustration Tool

4.15. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halliwell, B. Understanding mechanisms of antioxidant action in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, F.; Zocchi, M.; Alimohammadi, F.; Harris, I.S. Regulation of antioxidants in cancer. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, C.R.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Promotes Cancer Cell Survival through Calcium Signaling. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Solis, C.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Torres-Ramos, M.; Jimenez-Farfan, D.; Cruz Salgado, A.; Serrano-Garcia, N.; Osorio-Rico, L.; Sotelo, J. Multiple molecular and cellular mechanisms of action of lycopene in cancer inhibition. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 705121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, M.C.M.; Das, A.B. Potential Mechanisms of Action for Vitamin C in Cancer: Reviewing the Evidence. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Bhori, M.; Kasu, Y.A.; Bhat, G.; Marar, T. Antioxidants as precision weapons in war against cancer chemotherapy induced toxicity—Exploring the armoury of obscurity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottger, F.; Valles-Marti, A.; Cahn, L.; Jimenez, C.R. High-dose intravenous vitamin C, a promising multi-targeting agent in the treatment of cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.; Qiao, X.; Bergo, M.O. Effects of antioxidants on cancer progression. EMBO Mol. Med. 2025, 17, 1896–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, T.; Miyake, T.; Tani, M.; Uemoto, S. Diverse antitumor effects of ascorbic acid on cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 981547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y. Vitamin C at high concentrations induces cytotoxicity in malignant melanoma but promotes tumor growth at low concentrations. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.V.; Le Gal, K.; El Zowalaty, A.E.; Pehlivanoglu, L.E.; Garellick, V.; Gul, N.; Ibrahim, M.X.; Bergh, P.O.; Henricsson, M.; Wiel, C.; et al. Antioxidants Promote Intestinal Tumor Progression in Mice. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.A.; Thompson, I.M., Jr.; Tangen, C.M.; Crowley, J.J.; Lucia, M.S.; Goodman, P.J.; Minasian, L.M.; Ford, L.G.; Parnes, H.L.; Gaziano, J.M.; et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2011, 306, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whillier, S.; Raftos, J.E.; Chapman, B.; Kuchel, P.W. Role of N-acetylcysteine and cystine in glutathione synthesis in human erythrocytes. Redox Rep. 2009, 14, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, M.; Graciliano, N.G.; Moura, F.A.; Oliveira, A.C.M.; Goulart, M.O.F. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): Impacts on Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayin, V.I.; Ibrahim, M.X.; Larsson, E.; Nilsson, J.A.; Lindahl, P.; Bergo, M.O. Antioxidants accelerate lung cancer progression in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 221ra215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breau, M.; Houssaini, A.; Lipskaia, L.; Abid, S.; Born, E.; Marcos, E.; Czibik, G.; Attwe, A.; Beaulieu, D.; Palazzo, A.; et al. The antioxidant N-acetylcysteine protects from lung emphysema but induces lung adenocarcinoma in mice. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e127647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, K.; Ibrahim, M.X.; Wiel, C.; Sayin, V.I.; Akula, M.K.; Karlsson, C.; Dalin, M.G.; Akyurek, L.M.; Lindahl, P.; Nilsson, J.; et al. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 308re308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Kashif, M.; Qiao, X.; Tuksammel, E.; Larsson, L.G.; Okret, S.; Sayin, V.I.; Qian, H.; et al. A MYC-controlled redox switch protects B lymphoma cells from EGR1-dependent apoptosis. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Massague, J. Targeting metastatic cancer. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W. Taurine Inhibits Lung Metastasis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Modulating Macrophage Polarization Through PTEN-PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway. J. Immunother. 2024, 47, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiel, C.; Le Gal, K.; Ibrahim, M.X.; Jahangir, C.A.; Kashif, M.; Yao, H.; Ziegler, D.V.; Xu, X.; Ghosh, T.; Mondal, T.; et al. BACH1 Stabilization by Antioxidants Stimulates Lung Cancer Metastasis. Cell 2019, 178, 330–345.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Xiong, G.; Yun, F.; Feng, Y.; Ni, Q.; Wu, N.; Yang, L.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Palmitic Acid Promotes Lung Metastasis of Melanomas via the TLR4/TRIF-Peli1-pNF-kappaB Pathway. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Li, Q.; Shi, J.; Wei, J.; Li, P.; Chang, C.H.; Shultz, L.D.; Ren, G. Lung fibroblasts facilitate pre-metastatic niche formation by remodeling the local immune microenvironment. Immunity 2022, 55, 1483–1500.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, B.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. T Cell Dysfunction and Exhaustion in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, N. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanisms and cutting-edge therapeutic approaches. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, K.; Pravoverov, K.; Talmadge, J.E. Role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condamine, T.; Ramachandran, I.; Youn, J.I.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Regulation of tumor metastasis by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Li, Q.; Shi, J.; Li, P.; Hua, L.; Shultz, L.D.; Ren, G. Immunosuppressive reprogramming of neutrophils by lung mesenchymal cells promotes breast cancer metastasis. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eadd5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, V.X.; Sze, K.M.; Chan, L.K.; Ho, D.W.; Tsui, Y.M.; Chiu, Y.T.; Lee, E.; Husain, A.; Huang, H.; Tian, L.; et al. Antioxidant supplements promote tumor formation and growth and confer drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma by reducing intracellular ROS and induction of TMBIM1. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibellini, L.; Pinti, M.; Nasi, M.; De Biasi, S.; Roat, E.; Bertoncelli, L.; Cossarizza, A. Interfering with ROS Metabolism in Cancer Cells: The Potential Role of Quercetin. Cancers 2010, 2, 1288–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablina, A.A.; Budanov, A.V.; Ilyinskaya, G.V.; Agapova, L.S.; Kravchenko, J.E.; Chumakov, P.M. The antioxidant function of the p53 tumor suppressor. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luond, F.; Tiede, S.; Christofori, G. Breast cancer as an example of tumour heterogeneity and tumour cell plasticity during malignant progression. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, U.; Shenoy, P.S.; Bose, B. Opposing effects of low versus high concentrations of water soluble vitamins/dietary ingredients Vitamin C and niacin on colon cancer stem cells (CSCs). Cell Biol. Int. 2017, 41, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, M.; Shi, J.; Gong, Z.; Hua, L.; Li, Q.; Lim, B.; Zhang, X.H.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; et al. Lung mesenchymal cells elicit lipid storage in neutrophils that fuel breast cancer lung metastasis. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, M.; Shi, J.; Hua, L.; Gong, Z.; Li, Q.; Shultz, L.D.; Ren, G. Dual roles of neutrophils in metastatic colonization are governed by the host NK cell status. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Yaguchi, T.; Kawamura, N.; Kobayashi, A.; Sakurai, T.; Higuchi, H.; Takaishi, H.; Hibi, T.; Kawakami, Y. TGF-beta1 in tumor microenvironments induces immunosuppression in the tumors and sentinel lymph nodes and promotes tumor progression. J. Immunother. 2014, 37, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Nepovimova, E.; Adam, V.; Sivak, L.; Heger, Z.; Valko, M.; Wu, Q.; Kuca, K. Neutrophils in Cancer immunotherapy: Friends or foes? Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeagu, E.I. N2 Neutrophils and Tumor Progression in Breast Cancer: Molecular Pathways and Implications. Breast Cancer 2025, 17, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, L.; Zuo, J.; Feng, D. Tumor associated neutrophils governs tumor progression through an IL-10/STAT3/PD-L1 feedback signaling loop in lung cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 40, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrengues, J.; Shields, M.A.; Ng, D.; Park, C.G.; Ambrico, A.; Poindexter, M.E.; Upadhyay, P.; Uyeminami, D.L.; Pommier, A.; Kuttner, V.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science 2018, 361, eaao4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masucci, M.T.; Minopoli, M.; Del Vecchio, S.; Carriero, M.V. The Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tsung, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools-Lartigue, J.; Spicer, J.; McDonald, B.; Gowing, S.; Chow, S.; Giannias, B.; Bourdeau, F.; Kubes, P.; Ferri, L. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3446–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainglers, W.; Khamwong, M.; Chareonsudjai, S. N-acetylcysteine inhibits NETs, exhibits antibacterial and antibiofilm properties and enhances neutrophil function against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharazmi, A.; Nielsen, H.; Schiotz, P.O. N-acetylcysteine inhibits human neutrophil and monocyte chemotaxis and oxidative metabolism. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1988, 10, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Li, Q.; Shi, J.; Liu, E.T.; Shultz, L.D.; Ren, G. Lipid-laden lung mesenchymal cells foster breast cancer metastasis via metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells and natural killer cells. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 1960–1976 e1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Li, Q.; Shi, J.; Ren, G. An Artifact in Intracellular Cytokine Staining for Studying T Cell Responses and Its Alleviation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 759188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Wu, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, Q.; Gong, Z. Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Facilitates Breast Cancer Metas-Tasis via Immunosuppressive Reprogramming of Neutrophils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010526

Zhang J, Wang D, Wang H, Wu Q, Liu M, Li Q, Gong Z. Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Facilitates Breast Cancer Metas-Tasis via Immunosuppressive Reprogramming of Neutrophils. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010526

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiawen, Di Wang, Huige Wang, Qiuyu Wu, Menghao Liu, Qing Li, and Zheng Gong. 2026. "Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Facilitates Breast Cancer Metas-Tasis via Immunosuppressive Reprogramming of Neutrophils" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010526

APA StyleZhang, J., Wang, D., Wang, H., Wu, Q., Liu, M., Li, Q., & Gong, Z. (2026). Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Facilitates Breast Cancer Metas-Tasis via Immunosuppressive Reprogramming of Neutrophils. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010526