Water-Dispersible Supramolecular Nanoparticles Formed by Dicarboxyl-bis-pillar[5]arene/CTAB Host–Guest Interaction as an Efficient Delivery System of Quercetin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

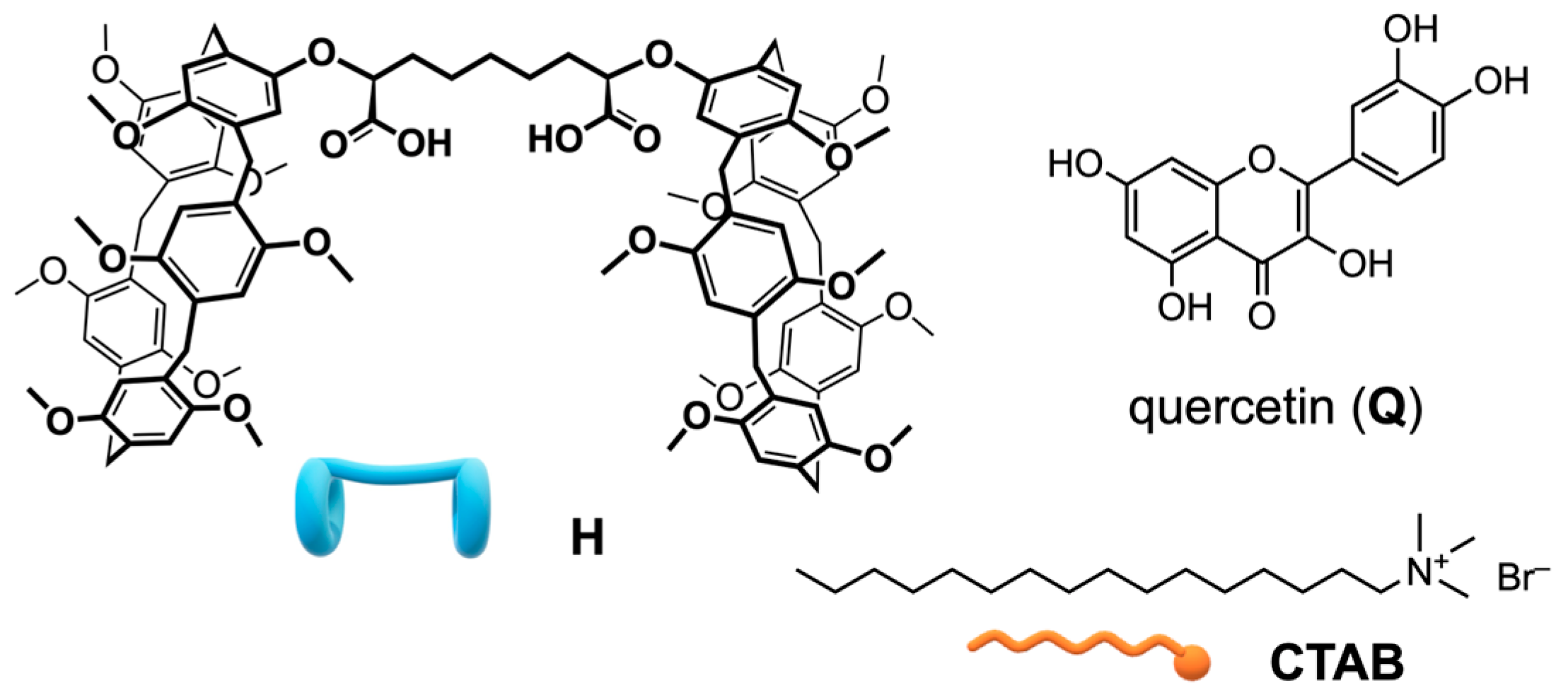

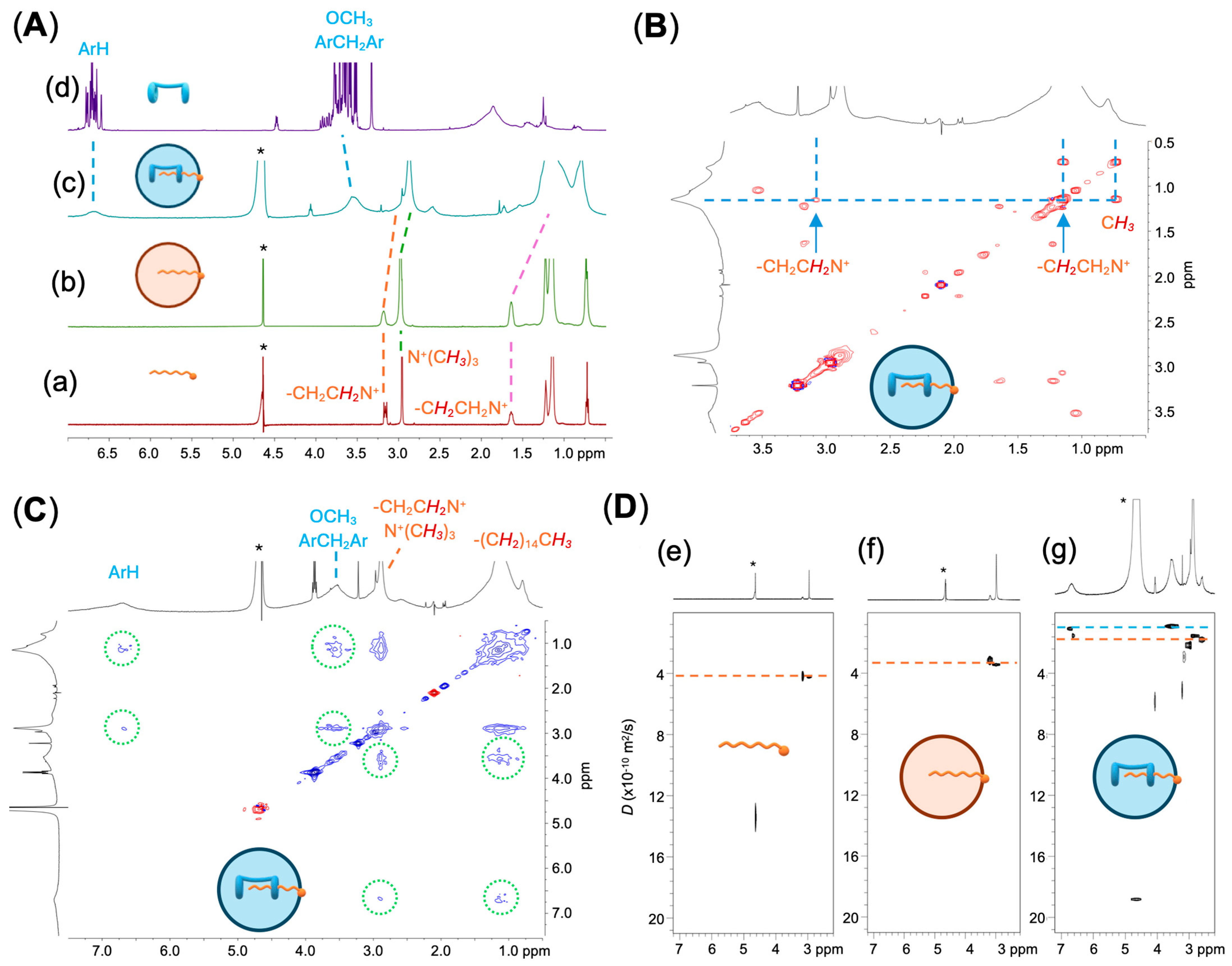

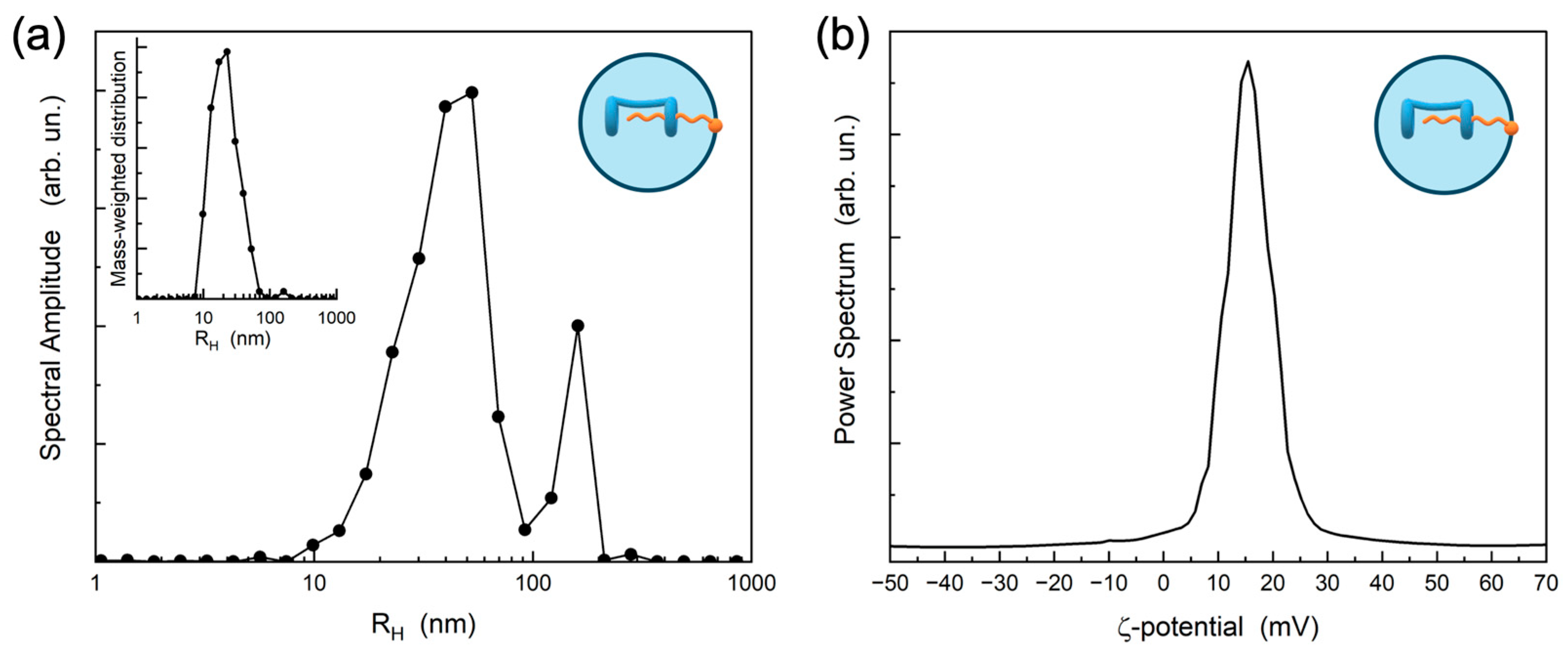

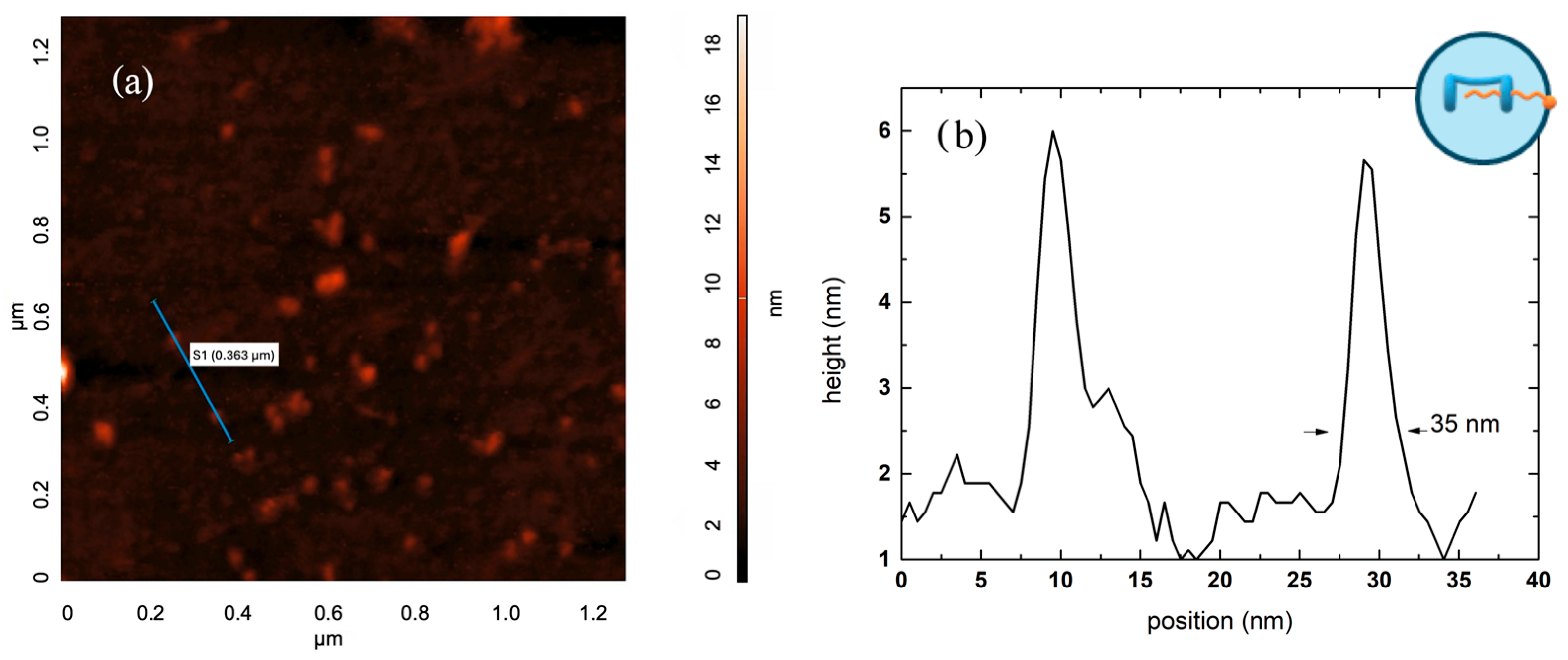

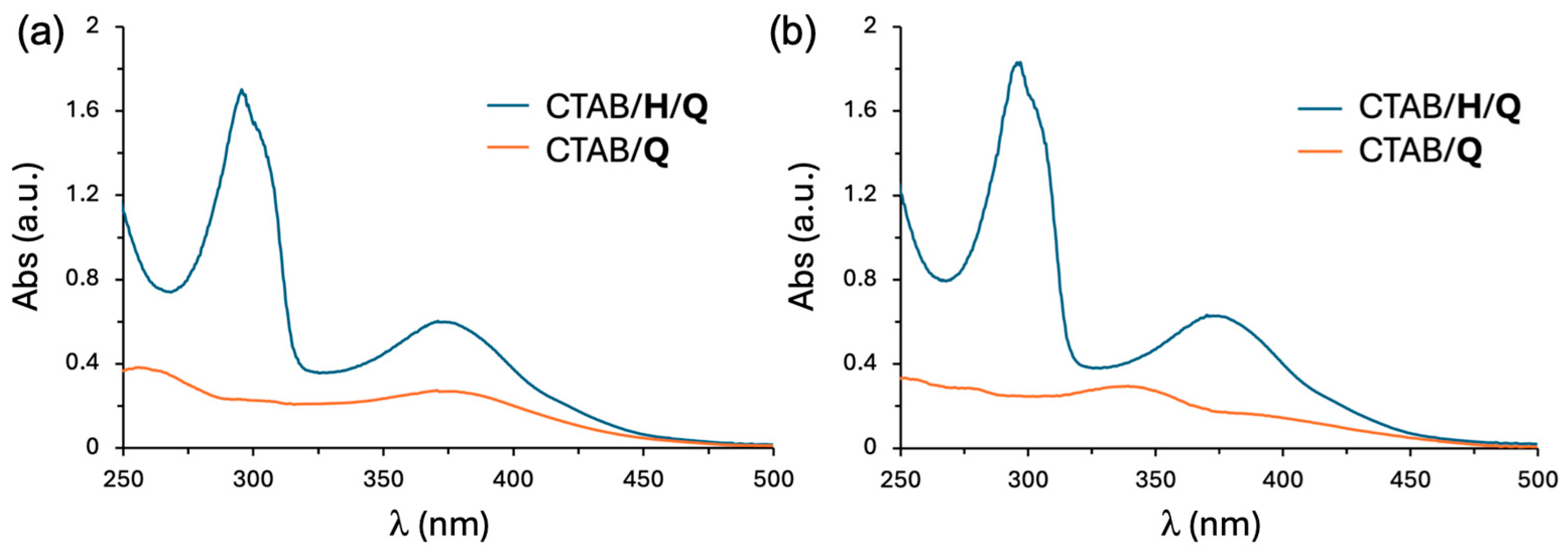

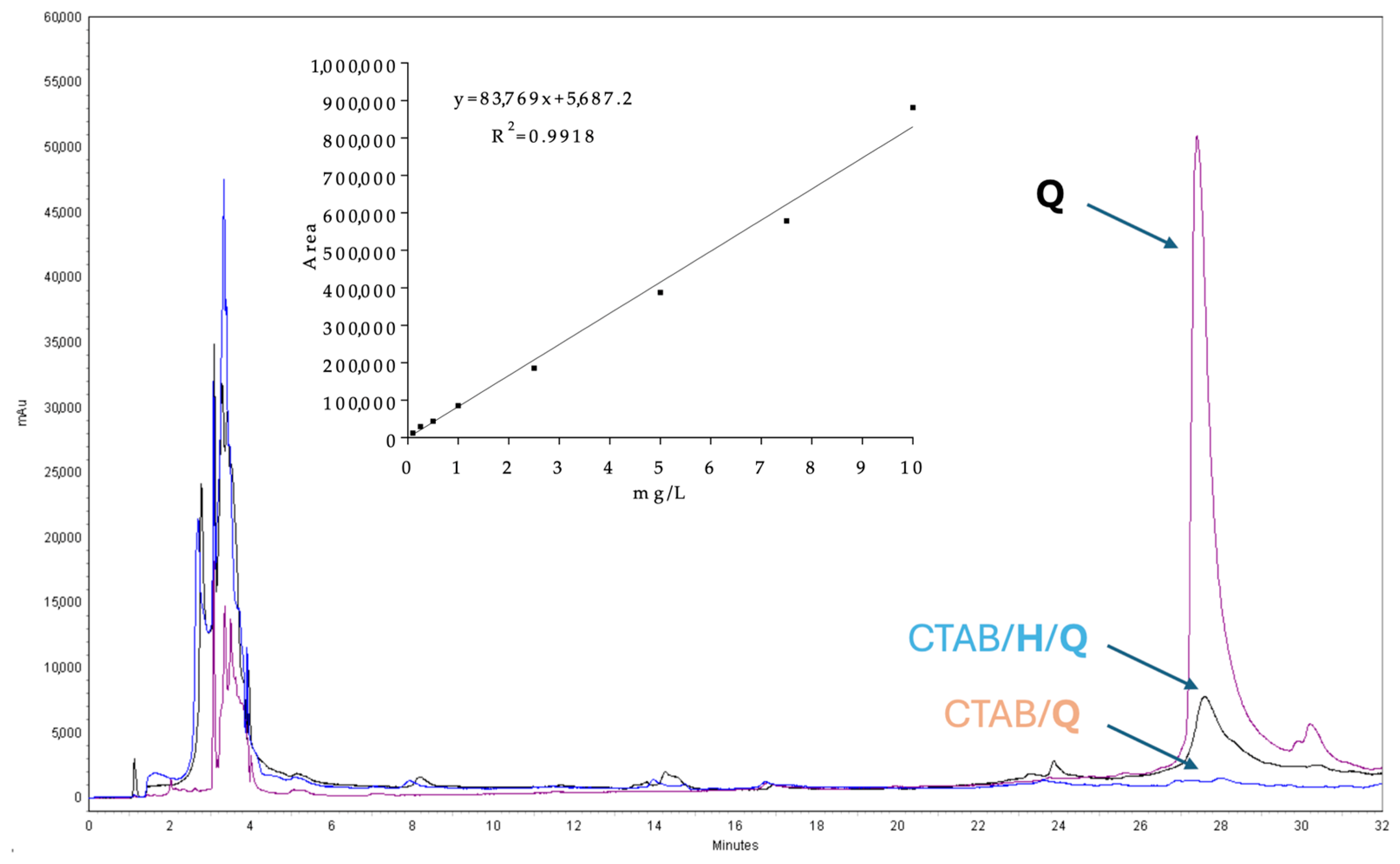

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Supramolecular Nanoparticles (SNPs)

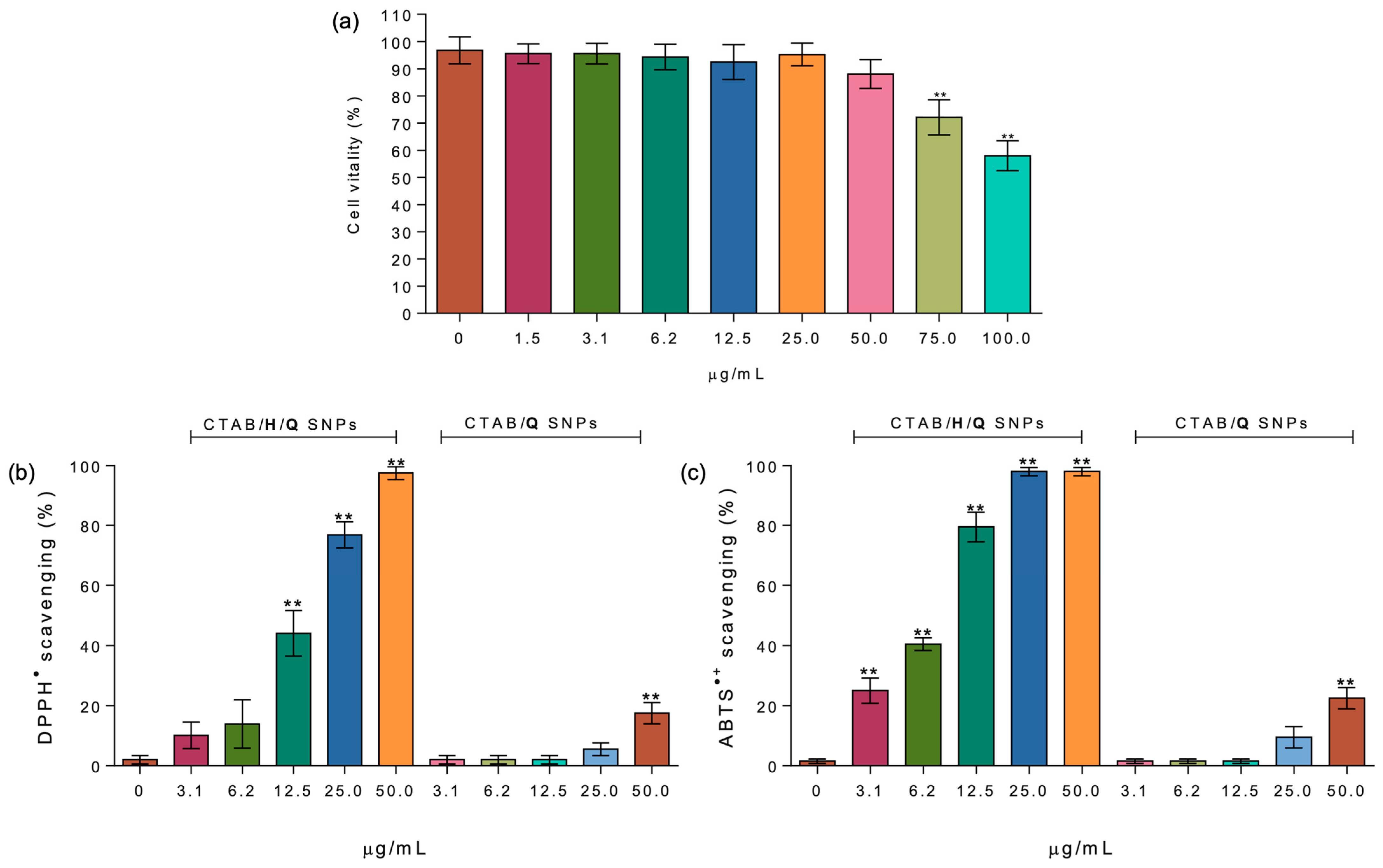

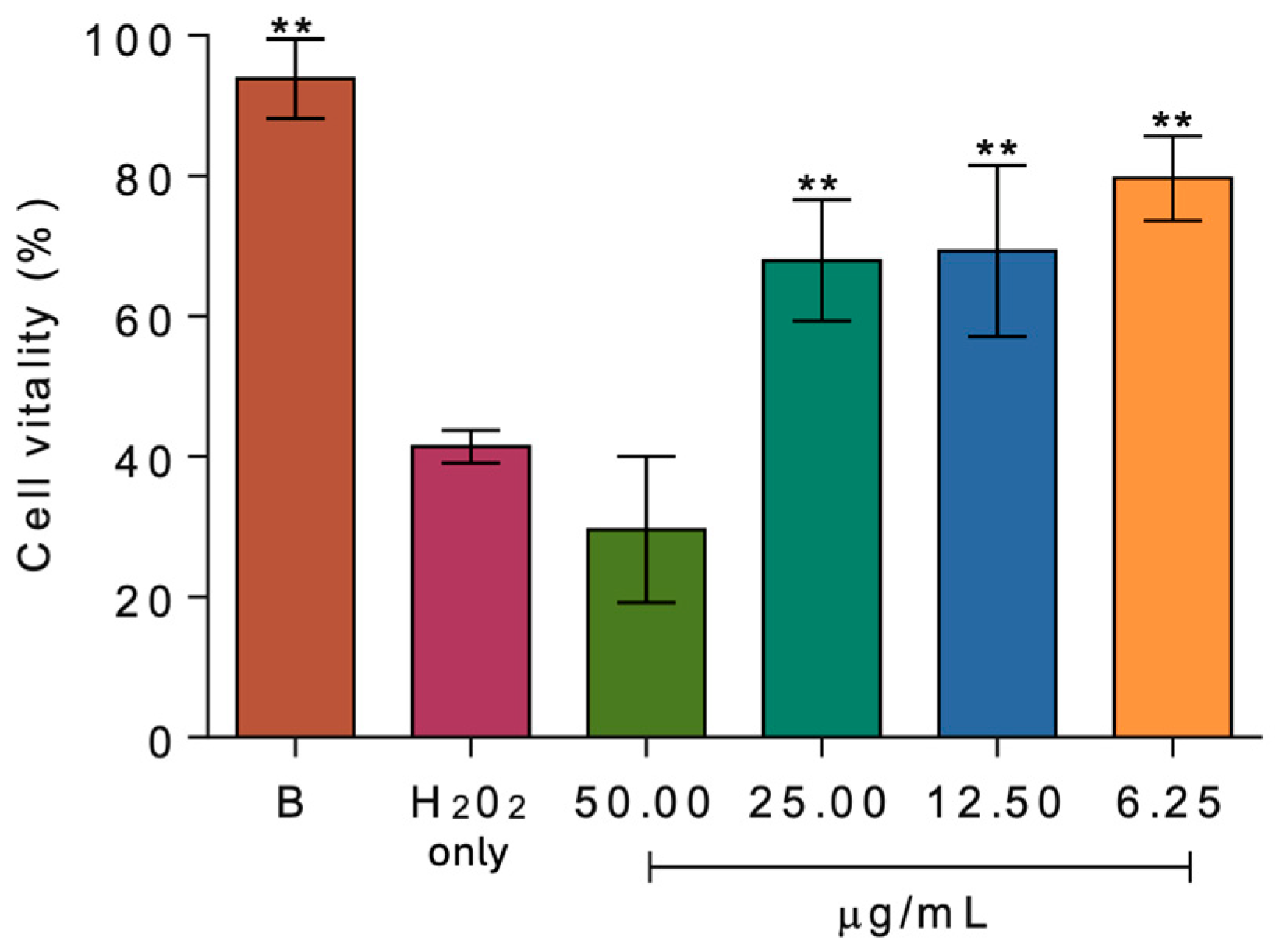

2.2. Biological Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental

3.2. Preparation of Supramolecular Nanoparticles (SNPs)

3.3. Stability Study

3.4. Preparation of Quercetin-Loaded SNPs

3.5. Two-Dimensional TOCSY, 2D NOESY and DOSY NMR

3.6. Dynamic Light Scattering

3.7. Electrophoretic Light Scattering (Photon Correlation Spectroscopy)

3.8. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

3.9. Cell Culture

3.10. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.11. Cellular Uptake

3.12. Cytoprotective Assay Against Oxidative Damage Induced by H2O2

3.13. 2,2-Diphenylpyrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Assay

3.14. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

3.15. ABTS Assay

3.16. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| BODIPY | 4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| D | Self-diffusion coefficient |

| DAD | Diode Array Detection |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DOSY | Diffusion-Order Spectroscopy |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ET | Electron transfer |

| FRAP | Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| HAT | Hydrogen atom transfer |

| LC% | Drug loading capacity |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| PALS | Phase Analysis Light Scattering |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| Rcf | Relative Centrifugal Field |

| RH | Average hydrodynamic radius |

| Rt | Retention time |

| RP-HPLC | Reverse Phase–High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| SNPs | Supramolecular nanoparticles |

| TPTZ | 2,4,6-Tripyridyl-s-triazine |

References

- Yadav, K.S.; Soni, G.; Choudhary, D.; Khanduri, A.; Bhandari, A.; Joshi, G. Microemulsions for Enhancing Drug Delivery of Hydrophilic Drugs: Exploring Various Routes of Administration. Med. Drug Discov. 2023, 20, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, N.; Alzahrani, A.K.; Basha, W.J.; Kizilbash, N.; Zaidi, A.; Ambreen, J.; Khachfe, H.M. Microemulsions: Unique Properties, Pharmacological Applications, and Targeted Drug Delivery. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021, 3, 754889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguera, J.L.; Burguera, M. Analytical applications of emulsions and microemulsions. Talanta 2012, 96, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.-X.; Hez, Z.-G.; Gao, J.-Q. Microemulsions as drug delivery systems to improve the solubility and the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2010, 7, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennick, J.J.; Johnston, A.P.R.; Parton, R.G. Key Principles and Methods for Studying the Endocytosis of Biological and Nanoparticle Therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shao, H.; Gao, L.; Li, H.; Sheng, H.; Zhu, L. Nano-drug co-delivery system of natural active ingredients and chemotherapy drugs for cancer treatment: A review. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 2130–2161, Correction in Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeberg, J.M.; Kaufmann, P.; Kroon, K.G.; Höglund, P. Lipid Drug Delivery and Rational Formulation Design for Lipophilic Drugs with Low Oral Bioavailability, Applied to Cyclosporine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 20, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirinho, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Santos, A.O.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G. Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems: An Alternative Approach to Improve Brain Bioavailability of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs through Intranasal Administration. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, A.W.; Haenen, G.R.M.M.; Bast, A. Health Effects of Quercetin: From Antioxidant to Nutraceutical. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 585, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Trombetta, D.; Smeriglio, A.; Mandalari, G.; Romeo, O.; Felice, M.R.; Gattuso, G.; Nabavi, S.M. Food Flavonols: Nutraceuticals with Complex Health Benefits and Functionalities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasi, T.; Calderaro, A.; Barreca, D.; Tellone, E.; Trombetta, D.; Ficarra, S.; Smeriglio, A.; Mandalari, G.; Gattuso, G. Biotechnological Applications and Health-Promoting Properties of Flavonols: An Updated View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Hu, M.-J.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Cui, Y.-L. Antioxidant Activities of Quercetin and Its Complexes for Medicinal Application. Molecules 2019, 24, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xu, T.; Li, Y.; Ren, J. Mapping the Effect of Plant-Based Extracts on Immune and Tumor Cells from a Bioactive Compound Standpoint. Food Front. 2023, 4, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Hanif, M.; Mahmood, K.; Ameer, N.; Chughtai, F.R.S.; Abid, U. An Insight into Anticancer, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Quercetin: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas, K.; King, J.W.; Howard, L.R.; Monrad, J.K. Solubility and solution thermodynamic properties of quercetin and quercetin dihydrate in subcritical water. J. Food Eng. 2010, 100, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.; van Trip, J.M.; Mengelers, M.J.; de Vries, J.H.; Katan, M.B. Bioavailability of the dietary antioxidant flavonol quercetin in man. Cancer Lett. 1997, 114, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Acqua, S.; Miolo, G.; Innocenti, G.; Caffieri, S. The Photodegradation of Quercetin: Relation to Oxidation. Molecules 2012, 17, 8898–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarova, A.; Yakimova, L.; Mostovaya, O.; Kulikova, T.; Mikhailova, O.; Evtugyn, G.; Ganeeva, I.; Bulatov, E.; Stoikov, I. Encapsulation of the quercetin with interpolyelectrolyte complex based on pillar[5]arenes. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, C.; Mao, L.; Ma, P.; Liu, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. The biological activities, chemical stability, metabolism and delivery systems of quercetin: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomou, E.-M.; Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Saitani, E.-M.; Valsami, G.; Pippa, N.; Skaltsa, H. Recent Advances in Nanoformulations for Quercetin Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoshi, T.; Kanai, S.; Fujinami, S.; Yamagishi, T.; Nakamoto, Y. para-Bridged Symmetrical Pillar[5]arenes: Their Lewis Acid Catalyzed Synthesis and Host–Guest Property. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5022–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, M.; Yang, Y.; Chi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, F. Pillararenes, A New Class of Macrocycles for Supramolecular Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1294–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiyajith, C.; Shaikh, R.R.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Meguellati, K.; Yang, Y.-W. Biological and related applications of pillar[n]arenes. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 677–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Fan, C.; Cheng, G.; Wu, W.; Yang, C. Synthesis, enantioseparation and photophysical properties of planar-chiral pillar[5]arene derivatives bearing fluorophore fragments. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoshi, T.; Yamagishi, T.; Nakamoto, Y. Pillar-Shaped Macrocyclic Hosts Pillar[n]arenes: New Key Players for Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7937−8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Khalil-Crus, L.E.; Khashab, N.M.; Yu, G.; Huang, F. Pillararene-based supramolecular systems for theranostics and bioapplications. Sci. China Chem. 2021, 64, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chao, S.; Wu, L.; Liu, H.; Pei, Y.; James, T.D.; Pei, Z. Advances in the bioapplications of ionic pillararenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 8345–8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Xu, K.; Hou, D.; Li, C. Molecular Recognition of Water-soluble Pillar[n]arenes Towards Biomolecules and Drugs. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 58, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Jie, K.; Huang, F. Supramolecular Amphiphiles Based on Host−Guest Molecular Recognition Motifs. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7240–7303, Correction in Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Gao, D.; Tian, C.; Chen, J.; Meng, Q. Macrocycle-based self-assembled amphiphiles for co-delivery of therapeutic combinations to tumor. Colloids Surf. B 2025, 246, 114383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarova, A.; Yakimova, L.; Filimonova, D.; Stoikov, I. Surfactant Effect on the Physicochemical Characteristics of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Based on Pillar[5]arenes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Hu, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Yao, Y. Recent development of pillar[n]arene-based amphiphiles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y. Pillararene-based self-assembled amphiphiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 5491–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Chen, X. Host–Guest Chemistry in Supramolecular Theranostics. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3041–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Jin, M.; Yang, K.; Pei, Y.; Pei, Z. Supramolecular delivery systems based on pillararenes. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13626–13640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, W.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, S.; Kovaleva, E.G.; Liang, F.; Tian, D.; Liu, J.; Abdelhameed, R.M.; Cheng, J.; et al. Controlled release of drug molecules by pillararene-modified nanosystems. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 3255–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Qiu, H. Histidine-modified pillar[5]arene-functionalized mesoporous silica materials for highly selective enantioseparation. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1727, 465011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Yu, G.; Li, J.; Huang, F. Photo-responsive self-assembly based on a water-soluble pillar[6]arene and an azobenzene-containing amphiphile in water. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3606–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, L.; Chen, Q.; Shi, B.; Huang, F. Enhancing the solubility and bioactivity of anticancer drug tamoxifen by water-soluble pillar[6]arene-based host–guest complexation. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 9749–9752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Xiao, T.; Lin, C.; Pan, Y.; Wang, L. pH-responsive supramolecular vesicles based on water-soluble pillar[6]arene and ferrocene derivative for drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10542−10549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-L.; Peng, H.-Q.; Niu, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Tung, C.-H.; Yang, Q.-Z. Artificial light-harvesting supramolecular polymeric nanoparticles formed by pillar[5]arene-based host–guest interaction. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Zhao, Q.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y. Pillar[5]arene based supramolecular polymer for a singlet oxygen reservoir. Polym. Chem. 2022, 13, 4578–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boominathan, M.; Arunachalam, M. Formation of Supramolecular Polymer Network and Single-Chain Polymer Nanoparticles via Host–Guest Complexation from Pillar[5]arene Pendant Polymer. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 4368–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Teng, K.-X.; Ding, Y.-F.; Yue, L.; Wang, R. Dual stimuli-responsive bispillar[5]arene-based nanoparticles for precisely selective drug delivery in cancer cells. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2340–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, K.-X.; Niu, L.-Y.; Yang, Q.-Z. A Host–Guest Strategy for Converting the Photodynamic Agents from a Singlet Oxygen Generator to a Superoxide Radical Generator. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 5951–5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattuso, G.; Crisafulli, D.; Milone, M.; Mancuso, F.; Pisagatti, I.; Notti, A.; Parisi, M.F. Proton Transfer Mediated Recognition of Amines by Ionizable Macrocyclic Receptors. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 10743–10756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notti, A.; Pisagatti, I.; Nastasi, F.; Patanè, S.; Parisi, M.F.; Gattuso, G. Stimuli-Responsive Internally Ion-Paired Supramolecular Polymer Based on a Bis-pillar[5]arene Dicarboxylic Acid Monomer. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferro, M.; Crisafulli, D.; Mancuso, F.; Milone, M.; Puntoriero, F.; Irto, A.; Patanè, S.; Greco, V.; Giuffrida, A.; Pisagatti, I.; et al. A Pillar[5]arene-Based Three-Component Supramolecular Copolymer for the Fluorescence Detection of Spermine. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 6293–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; Gattuso, G.; Kohnke, F.H.; Notti, A.; Pappalardo, S.; Parisi, M.F.; Pisagatti, I.; Patanè, S.; Micali, N.; Villari, V. Self-Assembly of Amphiphilic Anionic Calix[4]arene and Encapsulation of Poorly Soluble Naproxen and Flurbiprofen. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 6468–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; Franco, D.; De Plano, L.M.; Gattuso, G.; Guglielmino, S.P.P.; Lentini, G.; Manganaro, N.; Marino, N.; Pappalardo, S.; Parisi, M.F.; et al. A Water-Soluble Pillar[5]arene as a New Carrier for an Old Drug. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 3192–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; De Plano, L.M.; Franco, D.; Gattuso, G.; Guglielmino, S.P.P.; Lando, G.; Notti, A.; Parisi, M.F.; Pisagatti, I. Antiadhesive and Antibacterial Properties of Pillar[5]arene-Based Multilayers. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10203–10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alva-Ensastegui, J.C.; Ramírez-Silva, M.T. Study of the interaction between polyphenol, quercetin and three micelles with different electric charges in acidic and aqueous media. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2023, 100, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. The interpretation of small molecule diffusion coefficients: Quantitative use of diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2020, 117, 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamardashvili, G.M.; Kaigorodova, E.Y.; Khodov, I.A.; Mamardashvili, N.Z. Interaction of cationic 5,10,15,20-tetra(N-methylpyridyl)porphyrin and its Co(III) complex with premicellar SDS aggregates: Structure and properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 400, 124549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’ubica, K.; Sebej, P.; Stacko, P.; Filippov, S.K.; Bogomolova, A.; Padilla, M.; Klán, P. CTAB/Water/Chloroform Reverse Micelles: A Closed or Open Association Model? Langmuir 2012, 28, 15185–15192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisagatti, I.; Barbera, L.; Gattuso, G.; Villari, V.; Micali, N.; Fazio, E.; Neri, F.; Parisi, M.F.; Notti, A. Tuning the aggregation of an amphiphilic anionic calix[5]arene by selective host–guest interactions with bola-type dications. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 7628–7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipov, V.P.; Arkhipov, R.V.; Filippov, A. Micellar Solubilization of Phenols with One or Two Hydroxyl Groups Using Biological Surfactant Rhamnolipid. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2025, 63, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmedov, A.A.; Shurpik, D.N.; Padnya, P.L.; Khadieva, A.I.; Gamirov, R.R.; Panina, Y.V.; Gazizova, A.F.; Grishaev, D.Y.; Plemenkov, V.V.; Stoikov, I.I. Supramolecular Amphiphiles Based on Pillar[5]arene and Meroterpenoids: Synthesis, Self-Association and Interaction with Floxuridine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, G.; Notti, A.; Pappalardo, A.; Pappalardo, S.; Parisi, M.F.; Puntoriero, F. A supramolecular amphiphile from a new water-soluble calix[5]arene and n-dodecylammonium chloride. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles; Wiley-VCH: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gdowski, A.; Johnson, K.; Shah, S.; Gryczynski, I.; Vishwanatha, J.; Ranjan, A. Optimization and scale up of microfluidic nanolipomer production method for preclinical and potential clinical trials. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.; Liu, Y.; Shi, K.; Ma, D. Acetal-Functionalized Pillar[5]arene: A pH-Responsive and Versatile Nanomaterial for the Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Agents. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 2325−2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedaei, H.; Saboury, A.A.; Meratan, A.A.; Karami, L.; Sawyer, L.; Kaboudin, B.; Jooyan, N.; Ghasemi, A. Polyphenolic self-association accounts for redirecting a high-yielding amyloid aggregation. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 266, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniehelová, M.; Veverka, M.; Šturdík, E.; Jantová, S. Antioxidant action and cytotoxicity on HeLa and NIH-3T3 cells of new quercetin derivatives. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2013, 6, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.-Q. Chemical Methods to Evaluate Antioxidant Ability. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5675–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Bertin, R.; Froldi, G. EC50 estimation of antioxidant activity in DPPH• assay using several statistical programs. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micali, N.; Vybornyi, M.; Mineo, P.; Khorev, O.; Häner, R.; Villari, V. Hydrodynamic and Thermophoretic Effects on the Supramolecular Chirality of Pyrene-Derived Nanosheets. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9505–9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, A.; Cristaldi, D.A.; Fragalà, M.E.; Gattuso, G.; Pappalardo, A.; Villari, V.; Micali, N.; Pappalardo, S.; Parisi, M.F.; Purrello, R. Sequence, Stoichiometry, and Dimensionality Control in the Self-Assembly of Molecular Components. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 10439–10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancanelli, R.; Guardo, M.; Cannavà, C.; Guglielmo, G.; Ficarra, P.; Villari, V.; Micali, N.; Mazzaglia, A. Amphiphilic Cyclodextrins as Nanocarriers of Genistein: A Spectroscopic Investigation Pointing Out the Structural Properties of the Host/Drug Complex System. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 3141–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, T.; Vitale, V.; Oliva, S.; Villari, V.; Mauceri, A.; Fasulo, S.; Maisano, M. Alteration of Neurotransmission and Skeletogenesis in Sea Urchin Arbacia lixula Embryos Exposed to Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 199, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Y.; Chen, T.T.; Farag, M.A.; Teng, H.; Cao, H. A modified self-micro emulsifying liposome for bioavailabilityenhancement of quercetin and its biological effects. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Laganà, G.; Tellone, E.; Ficarra, S.; Leuzzi, U.; Galtieri, A.; Bellocco, E. Influences of Flavonoids on Erythrocyte Membrane and Metabolic Implication through Anionic Exchange Modulation. J. Membr. Biol. 2009, 230, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Laganà, G.; Ficarra, S.; Tellone, E.; Leuzzi, U.; Galtieri, A.; Bellocco, E. Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Properties of the Exotic Fruit Annona cherimola Mill. (Annonaceae). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2302–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, T.; Barreca, D.; Panuccio, M.R. Assessment of Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Potential of Jatropha curcas Grown in Southern Italy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milone, M.; Mazzaferro, M.; Calderaro, A.; Patanè, G.T.; Barreca, D.; Patanè, S.; Micali, N.; Villari, V.; Notti, A.; Parisi, M.F.; et al. Water-Dispersible Supramolecular Nanoparticles Formed by Dicarboxyl-bis-pillar[5]arene/CTAB Host–Guest Interaction as an Efficient Delivery System of Quercetin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010516

Milone M, Mazzaferro M, Calderaro A, Patanè GT, Barreca D, Patanè S, Micali N, Villari V, Notti A, Parisi MF, et al. Water-Dispersible Supramolecular Nanoparticles Formed by Dicarboxyl-bis-pillar[5]arene/CTAB Host–Guest Interaction as an Efficient Delivery System of Quercetin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010516

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilone, Marco, Martina Mazzaferro, Antonella Calderaro, Giuseppe T. Patanè, Davide Barreca, Salvatore Patanè, Norberto Micali, Valentina Villari, Anna Notti, Melchiorre F. Parisi, and et al. 2026. "Water-Dispersible Supramolecular Nanoparticles Formed by Dicarboxyl-bis-pillar[5]arene/CTAB Host–Guest Interaction as an Efficient Delivery System of Quercetin" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010516

APA StyleMilone, M., Mazzaferro, M., Calderaro, A., Patanè, G. T., Barreca, D., Patanè, S., Micali, N., Villari, V., Notti, A., Parisi, M. F., Pisagatti, I., & Gattuso, G. (2026). Water-Dispersible Supramolecular Nanoparticles Formed by Dicarboxyl-bis-pillar[5]arene/CTAB Host–Guest Interaction as an Efficient Delivery System of Quercetin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010516