Specific Glucagon Assay System Using a Receptor-Derived Glucagon-Binding Peptide Probe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

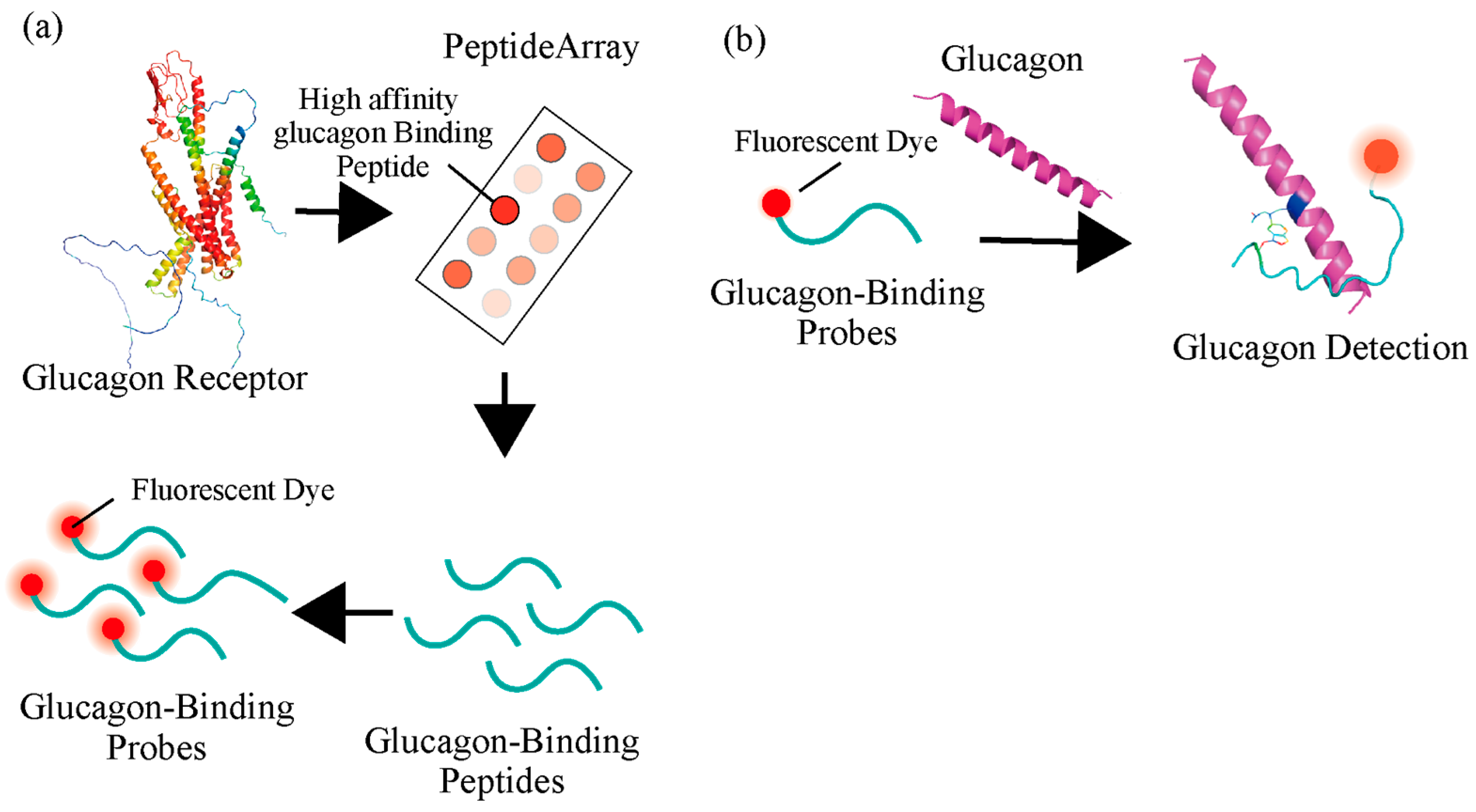

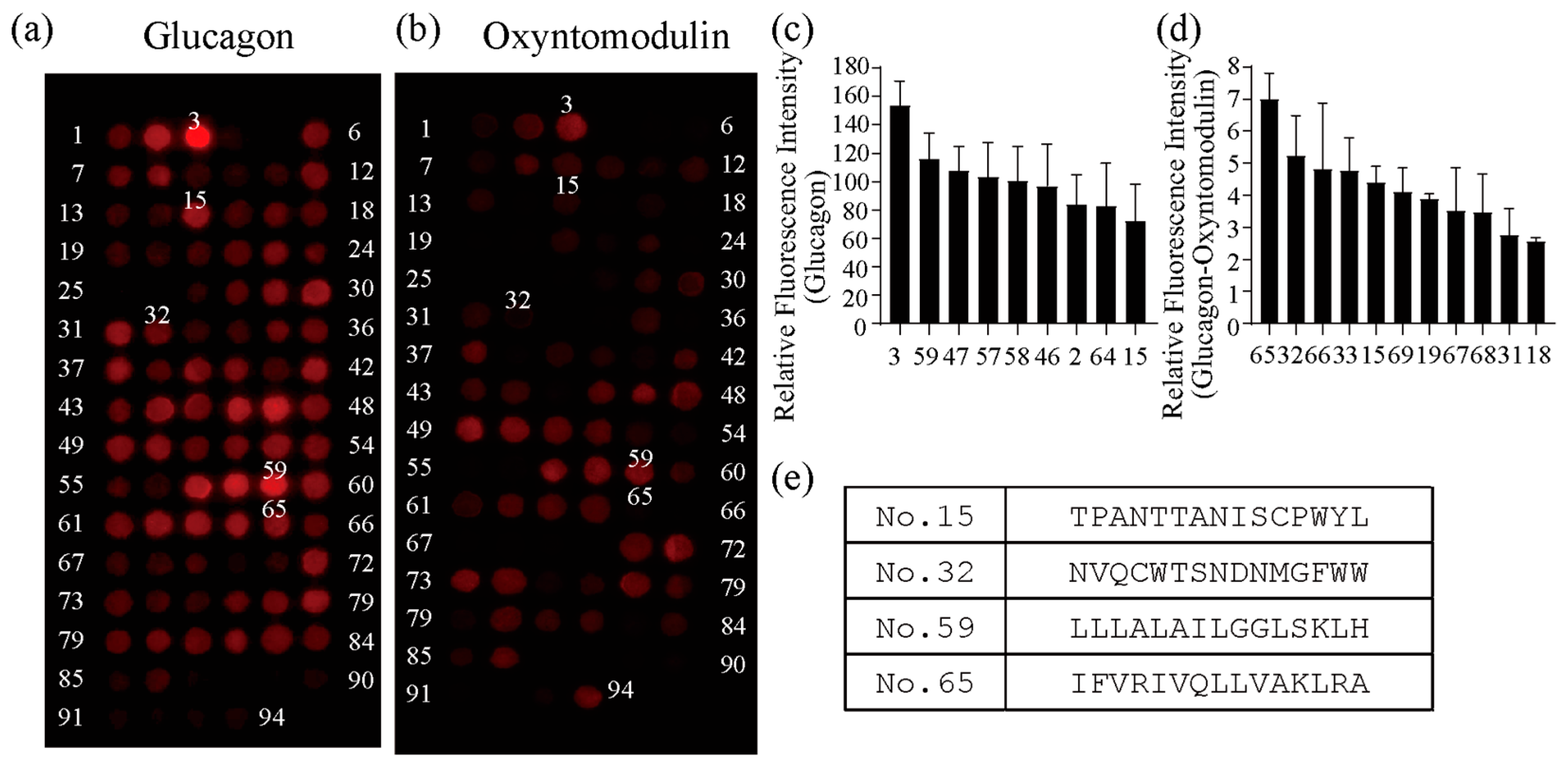

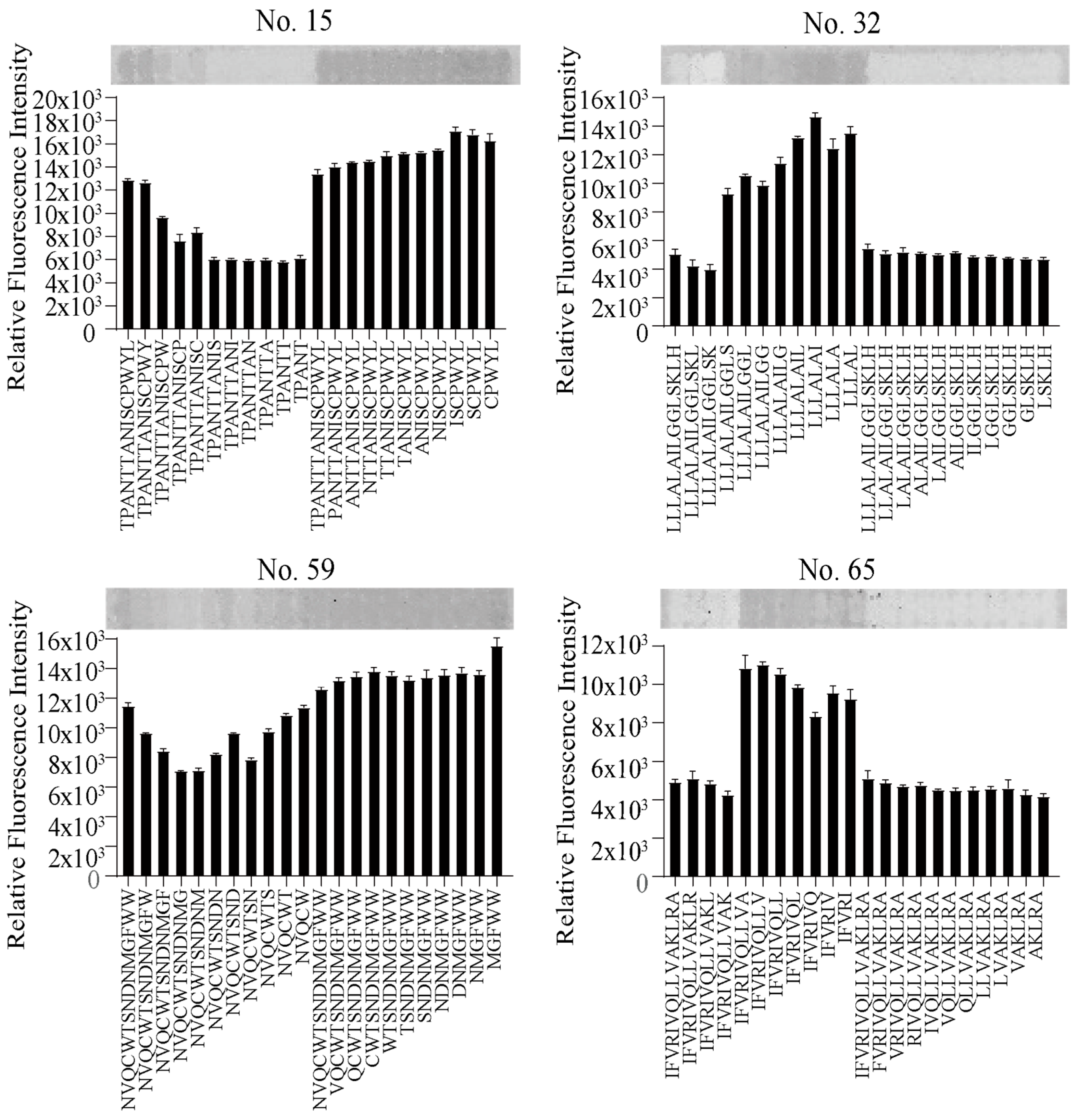

2.1. Development of GBP by Isolating Peptides from Glucagon Receptor Sequences

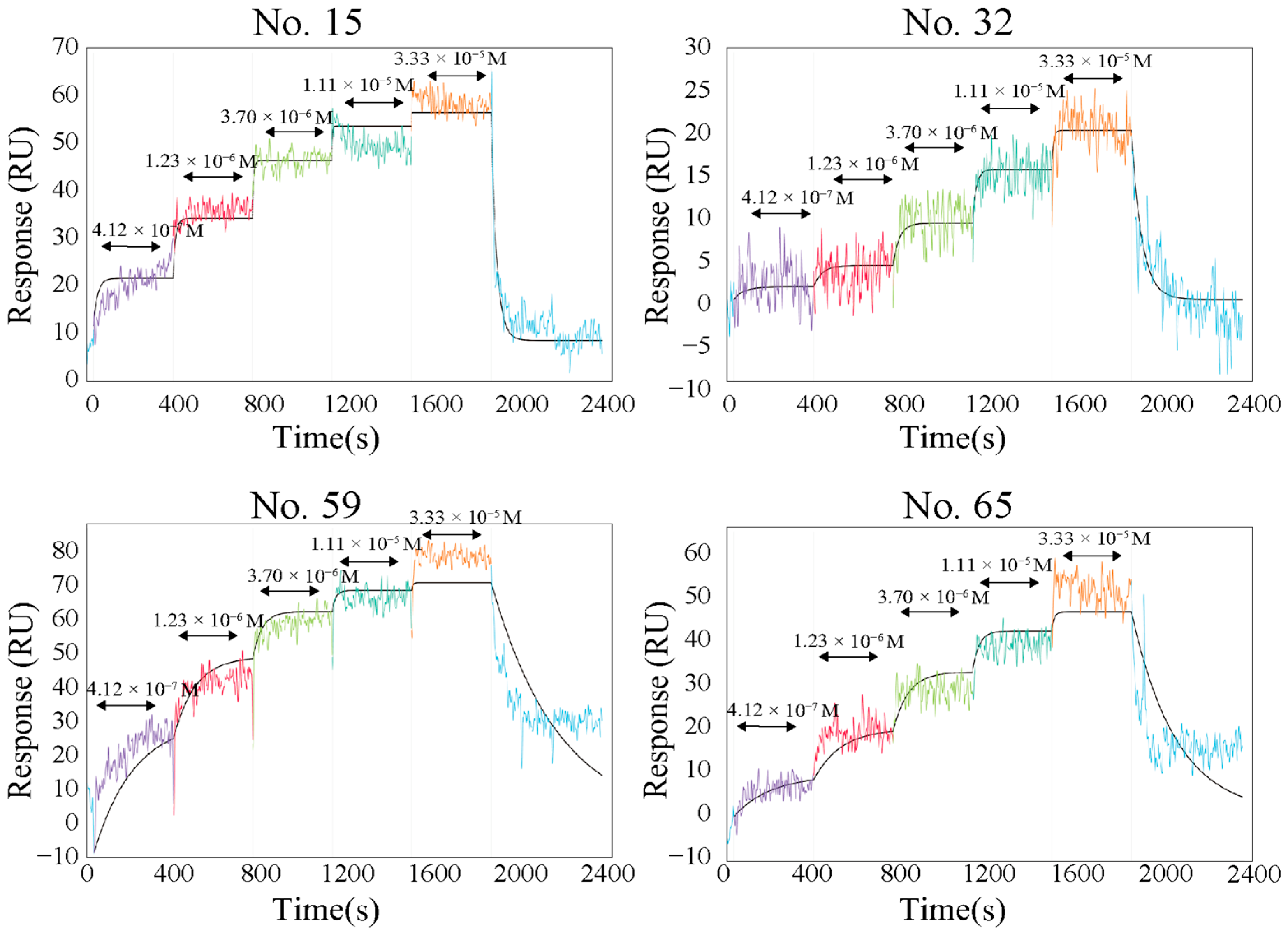

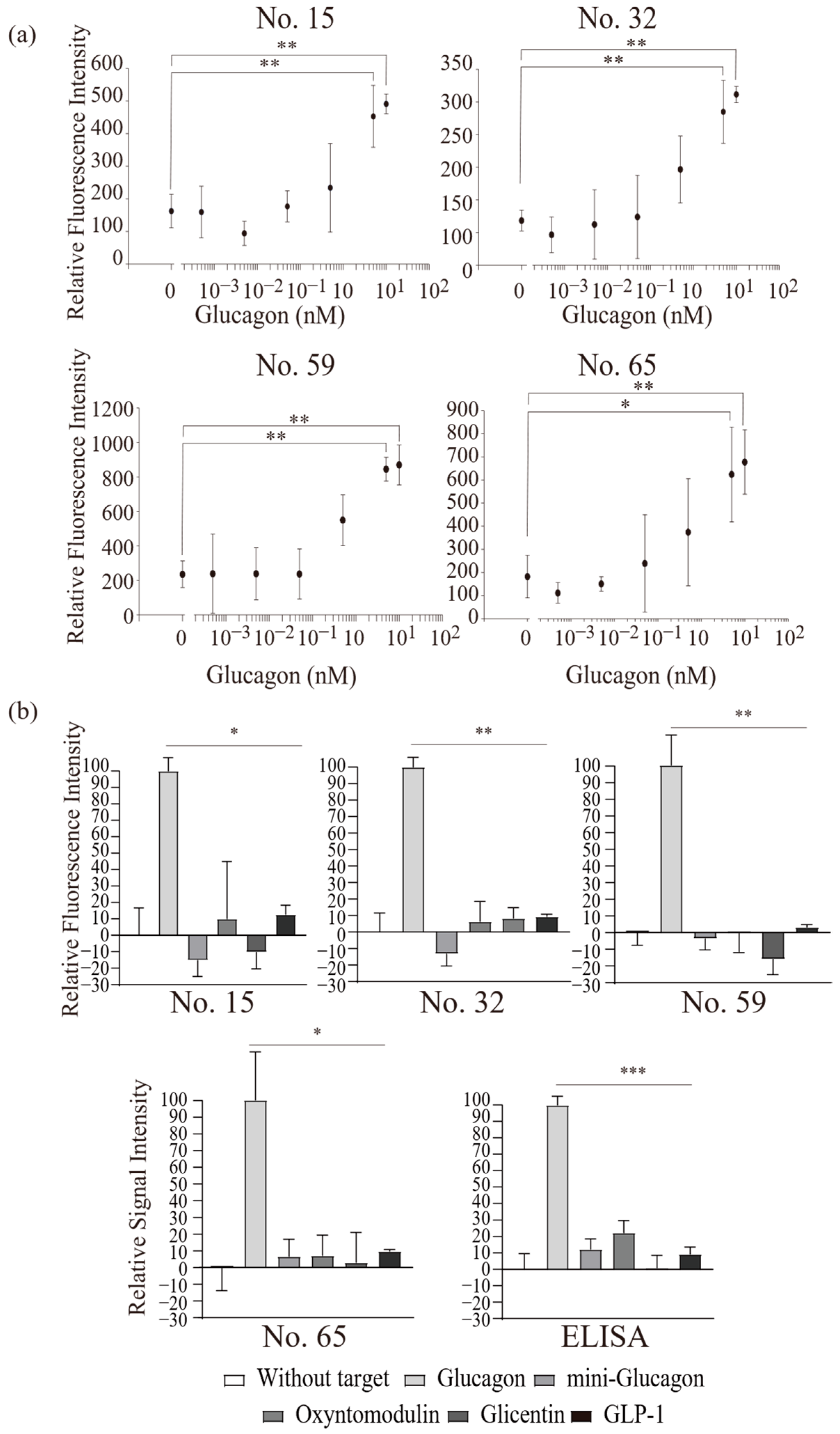

2.2. Functional Analysis of Screened Peptides as GBPs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Peptide Array Synthesis

3.2. Screening the Glucagon-Binding Peptide from Peptide Array

3.3. Intermolecular Interaction Analysis of Synthesized Peptides

3.4. GBP Synthesis by Modifying the Fluorescent Dye in Glucagon-Binding Peptides

3.5. Glucagon Assay Using the GBP

3.6. Limitations and Future Works

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murlin, J.R.; Clough, H.D.; Gibbs, C.B.F.; Stokes, A.M. Aqueous extracts of pancreas: I. Influence on the carbohydrate metabolism of depancreatized animals. J. Biol. Chem. 1923, 56, 253–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, J.E. Glucagon—An essential hormone. Am. J. Med. 1966, 41, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, E.W.; Duve, C. Origin and distribution of the hyperglycemic-glycogenolytic factor of the pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 175, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staub, A.; Sinn, L.; Behrens, O.K. Purification and crystallization of glucagon. J. Biol. Chem. 1955, 214, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromer, W.W.; Sinn, L.G.; Staub, A.; Behrens, O.K. The amino acid sequence of glucagon. Diabetes 1957, 6, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Massadi, O.; Fernø, J.; Diéguez, C.; Nogueiras, R.; Quiñones, M. Glucagon control on food intake and energy balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, C.G.; Porcellati, F.; Rossetti, P.; Bolli, G.B. Glucagon: The effects of its excess and deficiency on insulin action. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2006, 16, S28–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, L.; Shannon, C.; Gastaldelli, A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin: The master regulator of glucose metabolism. Metabolism 2022, 129, 155142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Berglund, E.D.; Wang, M.; Fu, X.; Yu, X.; Charron, M.J.; Burgess, S.C.; Unger, R.H. Metabolic manifestations of insulin deficiency do not occur without glucagon action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14972–14976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.H.; Cherrington, A.D. Glucagonocentric restructuring of diabetes: A pathophysiologic and therapeutic makeover. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsen, M.B.; Møller, N. Mini-review: Glucagon responses in type 1 diabetes—A matter of complexity. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e15009. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.D.; Finan, B.; Clemmensen, C.; DiMarchi, R.D.; Tschöp, M.H. The new biology and pharmacology of glucagon. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 721–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffort, J.; Lareyre, F.; Massalou, D.; Fénichel, P.; Panaïa-Ferrari, P.; Chinetti, G. Insights on glicentin, a promising peptide of the proglucagon family. Biochem. Med. 2017, 27, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, M.J.; Albrechtsen, N.W.; Pedersen, J.; Hartmann, B.; Christensen, M.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K.; Deacon, C.F.; Dragsted, L.O.; Holst, J.J. Specificity and sensitivity of commercially available assays for glucagon and oxyntomodulin measurement in humans. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 170, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèbvre, P.J. Glucagon and its family revisited. Diabetes Care 1995, 18, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocai, A. Action and therapeutic potential of oxyntomodulin. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, J.J.; Albrechtsen, N.J.W.; Gabe, M.B.N.G.; Rosenkilde, M.M. Oxyntomodulin: Actions and role in diabetes. Peptides 2018, 100, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataille, D.; Dalle, S. The forgotten members of the glucagon family. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, T.; Miyagawa, J.; Kusunoki, Y.; Miuchi, M.; Ikawa, T.; Akagami, T.; Tokuda, M.; Katsuno, T.; Kushida, A.; Inagaki, T.; et al. Postabsorptive hyperglucagonemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus analyzed with a novel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Diabetes Investig. 2016, 7, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Maruyama, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Togawa, T.; Ida, T.; Yoshida, M.; Miyazato, M.; Kitada, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Kashiwagi, A.; et al. A newly developed glucagon sandwich ELISA is useful for more accurate glucagon evaluation than the currently used sandwich ELISA in subjects with elevated plasma proglucagon-derived peptide levels. J. Diabetes Investig. 2023, 14, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechtsen, N.J.W.; Holst, J.J.; Cherrington, A.D.; Finan, B.; Gluud, L.L.; Dean, E.D.; Campbell, J.E.; Bloom, S.R.; Tan, T.M.; Knop, F.K.; et al. 100 years of glucagon and 100 more. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1378–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Torres, S.; Leung, P.J.Y.; Venkatesh, P.; Lutz, I.D.; Hink, F.; Huynh, H.-H.; Becker, J.; Yeh, A.H.-W.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N.R.; et al. De novo design of high-affinity binders of bioactive helical peptides. Nature 2024, 626, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiao, A.; Yang, L.; Eps, N.V.; Frederiksen, K.S.; Yang, D.; Dai, A.; Cai, X.; Zhang, H.; Yi, C.; et al. Structure of the glucagon receptor in complex with a glucagon analogue. Nature 2018, 553, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeto, H.; Ikeda, T.; Kuroda, A.; Funabashi, H. A BRET-based homogeneous insulin assay using interacting domains in the primary binding site of the insulin receptor. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 2764–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeto, H.; Ono, T.; Ikeda, T.; Hirota, R.; Ishida, T.; Kuroda, A.; Funabashi, H. Insulin sensor cells for the analysis of insulin secretion responses in single living pancreatic β cells. Analyst 2019, 144, 3765–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Wang, G.; Hu, X.; Zang, Y.; Maisonneuve, S.; Sedgwick, A.C.; Sessler, J.L.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; He, X.; et al. Cyclodextrin-Based Peptide Self-Assemblies (Spds) That Enhance Peptide-Based Fluorescence Imaging and Antimicrobial Efficacy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, W.; Qiu, P.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, L.; Guo, C.; Li, N.; Zang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhao, S.; Pan, Y.; et al. Orthogonally Engineered Albumin with Attenuated Macrophage Phagocytosis for the Targeted Visualization and Phototherapy of Liver Cancer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 17377–17388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Tong, P.; Xing, M.; Liu, J.; Hu, X.; James, T.D.; Zhou, D.; He, X. Fluorogenic Peptide Sensor Array Derived from Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Classifies Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Variants of Concern. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 21017–21024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoya, K.; Maiko, Y.; Fuko, H.; Takashi, T. Comparison of Exendin-4 and Its Single Amino Acid Substitutions as Parent Peptides for GLP-1 Receptor Imaging Probes. Molecules 2025, 30, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unson, C.G.; Wu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yoo, B.; Cheung, C.; Sakmar, T.P.; Merrifield, R.B. Roles of specific extracellular domains of the glucagon receptor in ligand binding and signaling. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 11795–11803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, S.; Wulff, B.S.; Madsen, K.; Bräuner-Osborne, H.; Knudsen, L.B. Different domains of the glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors provide the critical determinants of ligand selectivity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 138, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, C.; Lu, J.; Li, N.; Barkan, K.; Richards, G.O.; Roberts, D.J.; Skerry, T.M.; Poyner, D.; Pardamwar, M.; Reynolds, C.A.; et al. Modulation of glucagon receptor pharmacology by receptor activity-modifying protein-2 (RAMP2). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 23009–23022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okochi, M.; Muto, M.; Yanai, K.; Tanaka, M.; Onodera, T.; Wang, J.; Ueda, H.; Toko, K. Array-based rational design of short peptide probe-derived from an anti-TNT monoclonal antibody. ACS Comb. Sci. 2017, 19, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Suwatthanarak, T.; Arakaki, A.; Johnson, B.R.G.; Evans, S.D.; Okochi, M.; Staniland, S.S.; Matsunaga, T. Enhanced tubulation of liposome containing cardiolipin by MamY protein from magnetotactic bacteria. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1800087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Takagi, N.; Sano, T.; Chimuro, T. Design and synthesis of a novel fluorescent protein probe for easy and rapid electrophoretic gel staining by using a commonly available UV-based fluorescent imaging system. Electrophoresis 2013, 34, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yokoyama, K. Design and Synthesis of Intramolecular Charge Transfer-Based Fluorescent Reagents for the Highly-Sensitive Detection of Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17799–17802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shigeto, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamamura, S. Specific Glucagon Assay System Using a Receptor-Derived Glucagon-Binding Peptide Probe. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010515

Shigeto H, Suzuki Y, Yamamura S. Specific Glucagon Assay System Using a Receptor-Derived Glucagon-Binding Peptide Probe. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010515

Chicago/Turabian StyleShigeto, Hajime, Yoshio Suzuki, and Shohei Yamamura. 2026. "Specific Glucagon Assay System Using a Receptor-Derived Glucagon-Binding Peptide Probe" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010515

APA StyleShigeto, H., Suzuki, Y., & Yamamura, S. (2026). Specific Glucagon Assay System Using a Receptor-Derived Glucagon-Binding Peptide Probe. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010515