Rethinking DeepVariant: Efficient Neural Architectures for Intelligent Variant Calling

Abstract

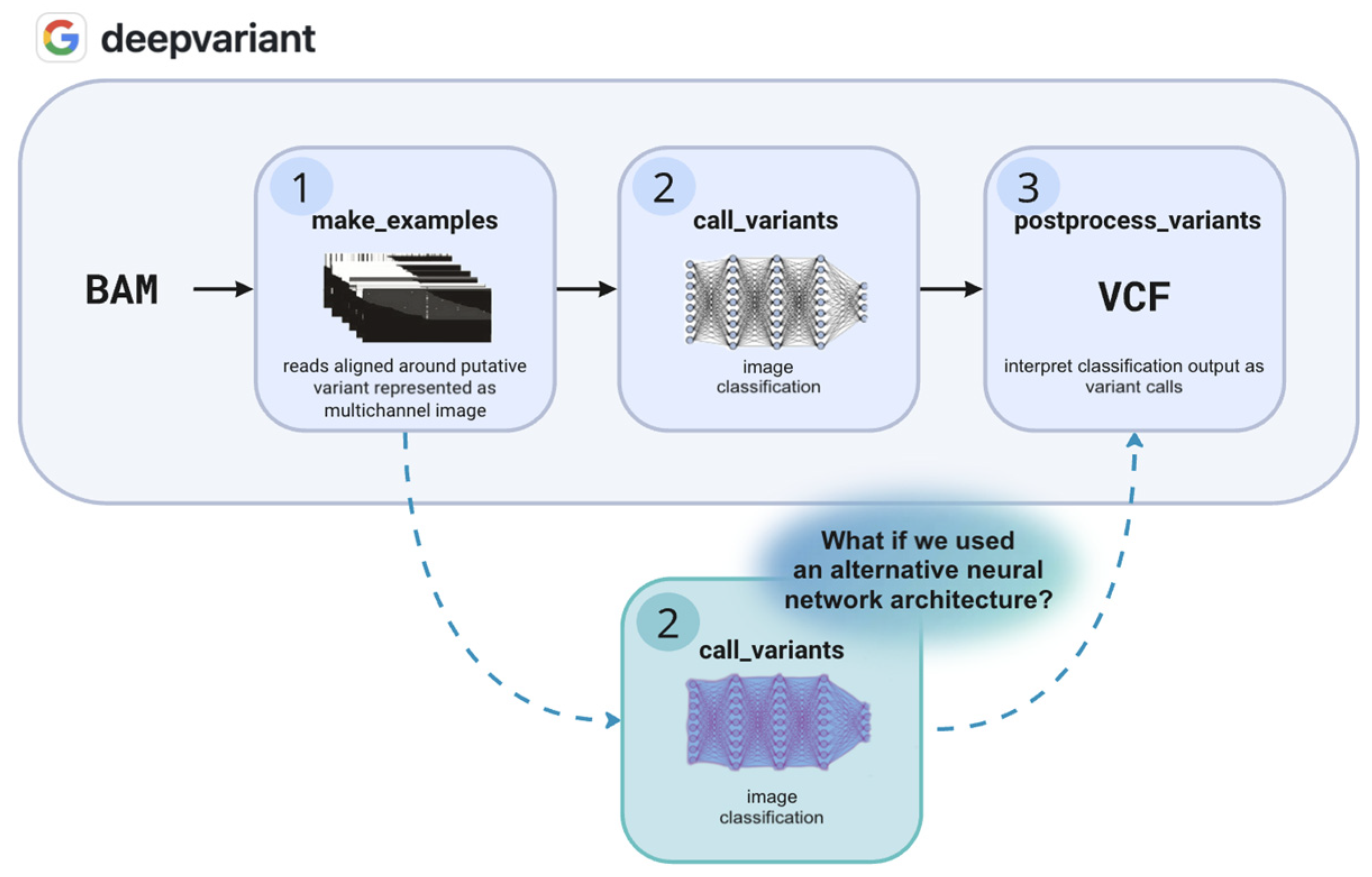

1. Introduction

2. Results

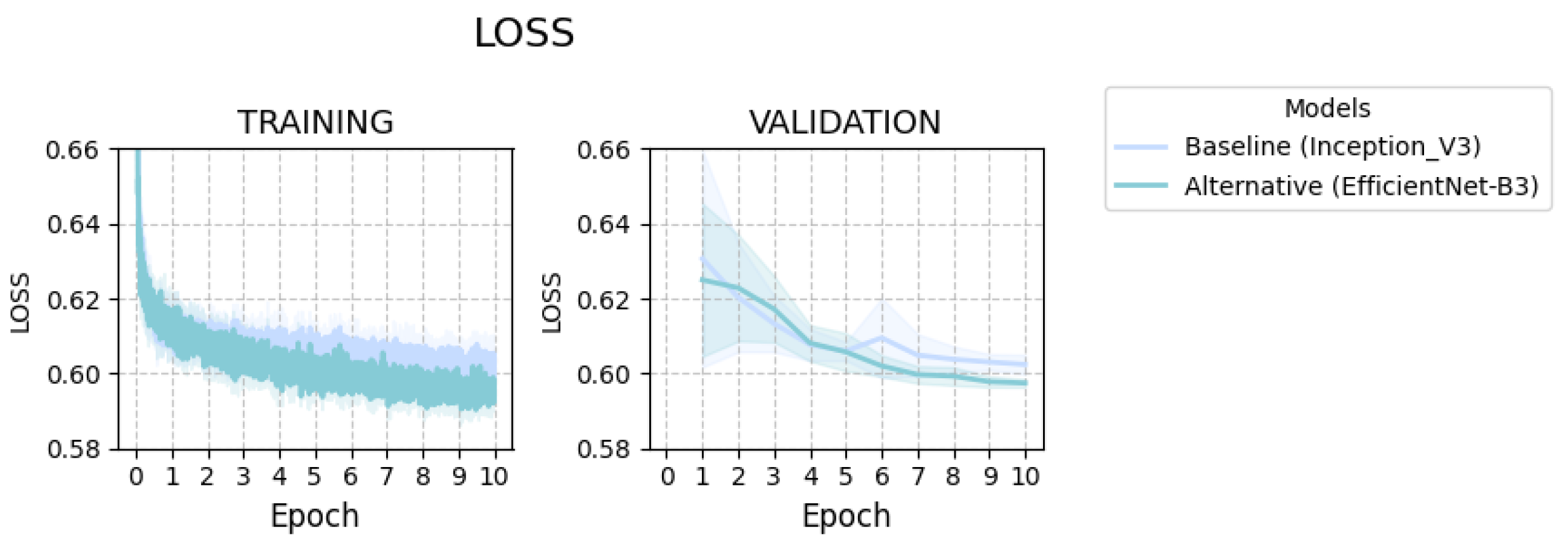

2.1. Training

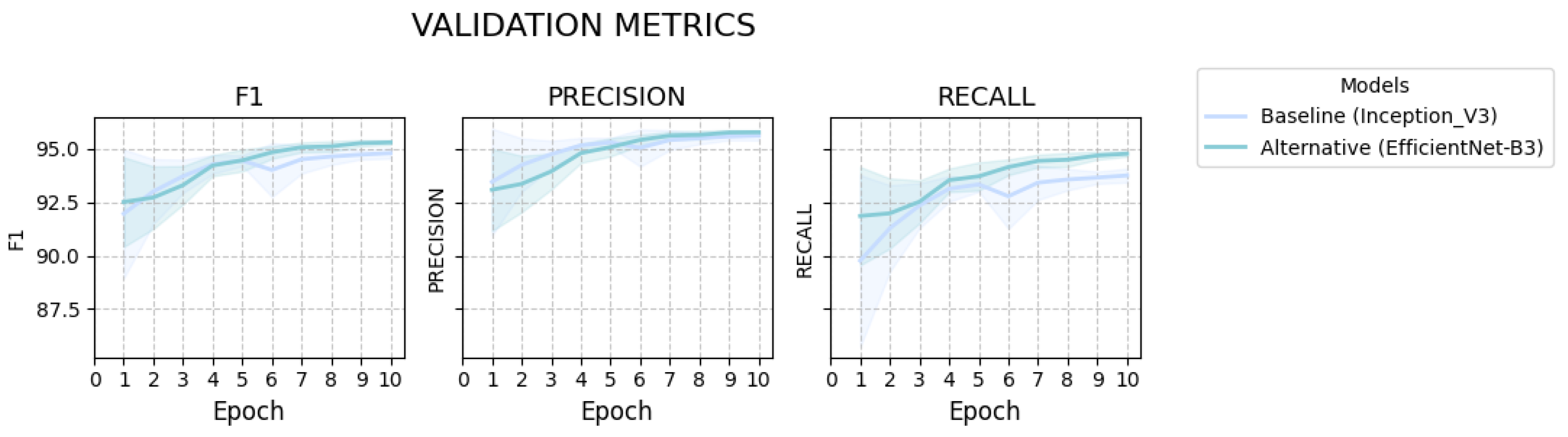

2.1.1. Learning Dynamics

2.1.2. Performance Evaluation

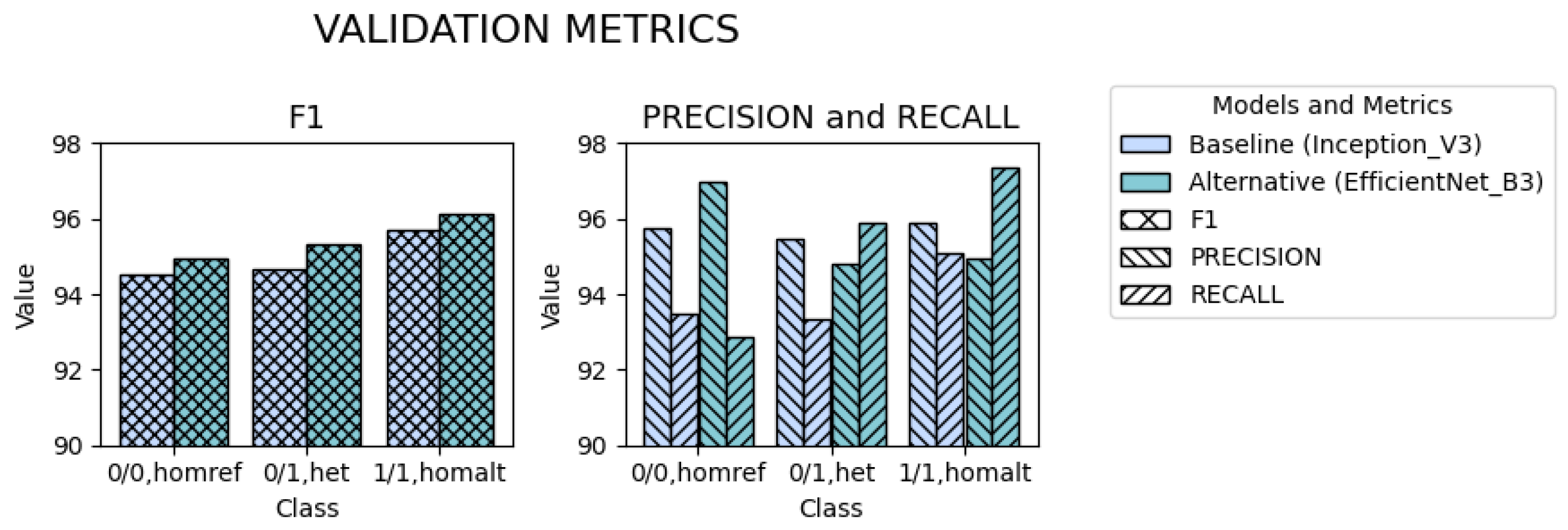

2.1.3. Performance Stratified by Genotype

2.2. Testing

2.3. Training Efficiency and Inference Time

3. Discussion

3.1. Alternative Model Performance

3.2. Limitations

3.3. Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Datasets

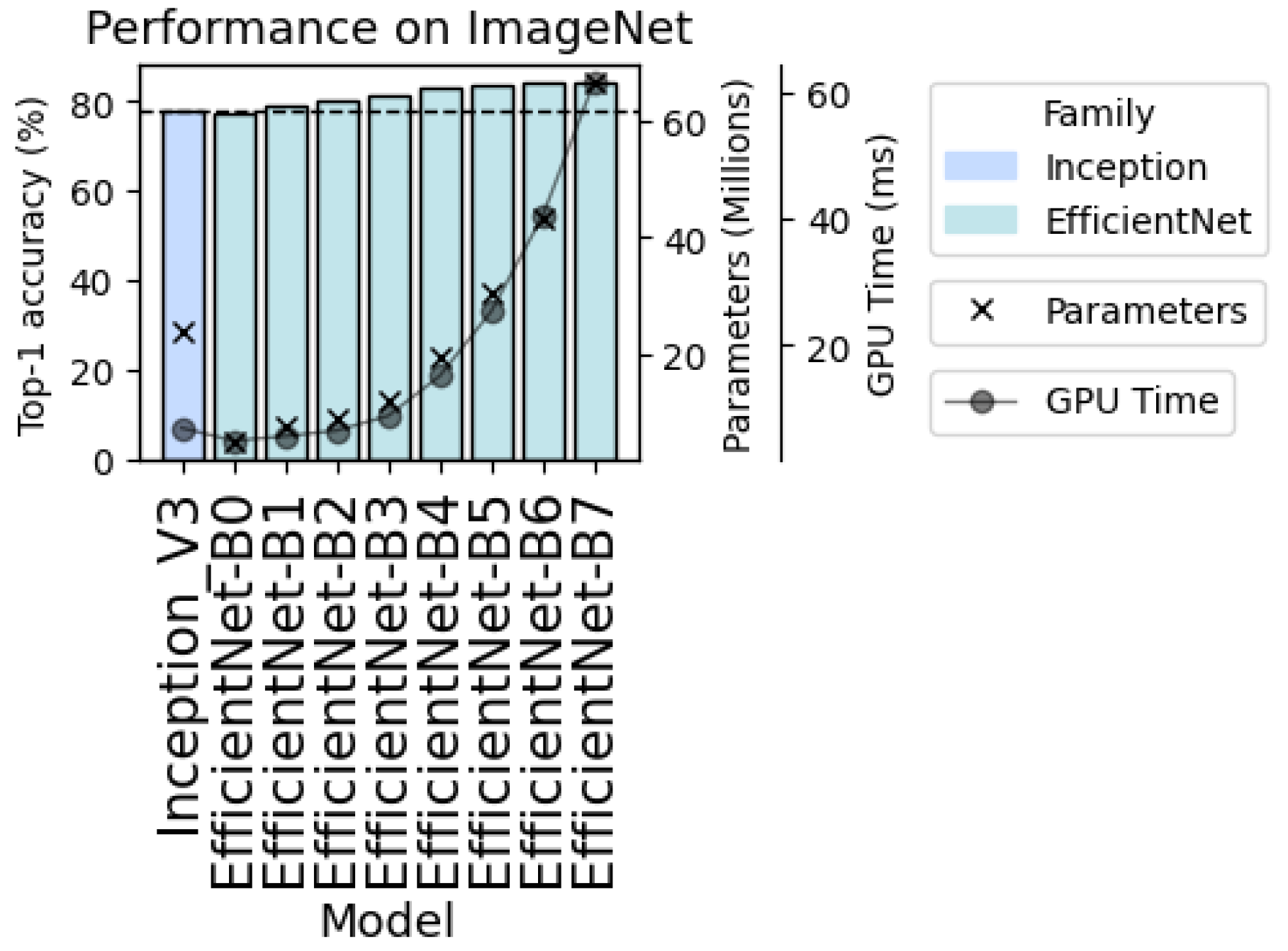

4.2. Selection of Alternative Model for Demonstration

4.3. Training

4.3.1. Training Pipeline Adaptation

4.3.2. Training Configurations

4.3.3. Evaluation of Performance During Training

4.4. Testing

4.5. Hardware and Environment

4.6. Code Availability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GATK | Genome Analysis Toolkit |

| GIAB | Genome in a Bottle |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| WGS | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

| WES | Whole-Exome Sequencing |

References

- Imperial, R.; Nazer, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Kam, A.E.; Pluard, T.J.; Bahaj, W.; Levy, M.; Kuzel, T.M.; Hayden, D.M.; Pappas, S.G.; et al. Matched Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) of Tumor Tissue with Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Analysis: Complementary Modalities in Clinical Practice. Cancers 2019, 11, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirrell, K.M.B.; O’Neill, H.C. Comparing the Diagnostic and Clinical Utility of WGS and WES with Standard Genetic Testing (SGT) in Children with Suspected Genetic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.; Paul, J.S.; Albrechtsen, A.; Song, Y.S. Genotype and SNP Calling from Next-Generation Sequencing Data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997, Correction in Biology 2024, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-S.; Khalak, A. Human Genome Assembly in 100 Minutes. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y. A comprehensive review of deep learning-based variant calling methods. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2024, 23, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantsiou, K.; Kathariou, S.; Winkler, A.; Skandamis, P.; Saint-Cyr, M.J.; Rouzeau-Szynalski, K.; Amézquita, A. Next Generation Microbiological Risk Assessment: Opportunities of Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) for Foodborne Pathogen Surveillance, Source Tracking and Risk Assessment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 287, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.P.; Petersen, B.L.; Johansen, I.E.; Niu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chamberlain, C.A.; Met, Ö.; Wandall, H.H.; Frödin, M. indel detection, the ‘Achilles heel’ of precise genome editing: A survey of methods for accurate profiling of gene editing induced indels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11958–11981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzey, D.; Evans, E.A.; Lieber, C. Understanding the Basics of NGS: From Mechanism to Variant Calling. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2015, 3, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibragimov, A.; Senotrusova, S.; Markova, K.; Karpulevich, E.; Ivanov, A.; Tyshchuk, E.; Grebenkina, P.; Stepanova, O.; Sirotskaya, A.; Kovaleva, A.; et al. Deep Semantic Segmentation of Angiogenesis Images. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakov, E.; Naumov, A.; Fomberg, V.; Vishnyakova, P.; Asaturova, A.; Badlaeva, A.; Tregubova, A.; Karpulevich, E.; Sukhikh, G.; Fatkhudinov, T. EndoNet: A Model for the Automatic Calculation of H-Score on Histological Slides. Informatics 2023, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R.; Chang, P.-C.; Alexander, D.; Schwartz, S.; Colthurst, T.; Ku, A.; Newburger, D.; Dijamco, J.; Nguyen, N.; Afshar, P.T.; et al. A Universal SNP and Small-indel Variant Caller Using Deep Neural Networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananev, V.V.; Skorik, S.N.; Shaklein, V.V.; Avetisyan, A.A.; Teregulov, Y.E.; Turdakov, D.Y.; Gliner, V.; Schuster, A.; Karpulevich, E.A. Assessment of the impact of non-architectural changes in the predictive model on the quality of ECG classification. In Proceedings of the Institute for System Programming of the RAS (Proceedings of ISP RAS), Moscow, Russia, 2–3 December 2021; Volume 33, pp. 87–98. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Imoto, S. Genome analysis through image processing with deep learning models. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 69, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. Improving the Accuracy of Genomic Analysis with DeepVariant 1.0. 18 September 2020. Available online: https://research.google/blog/improving-the-accuracy-of-genomic-analysis-with-deepvariant-10/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cook, D.E.; Venkat, A.; Yelizarov, D.; Pouliot, Y.; Chang, P.-C.; Carroll, A.; De La Vega, F.M. A deep-learning-based RNA-seq germline variant caller. Bioinform. Adv. 2023, 3, vbad062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.; Cook, D.; Nattestad, M.; Brambrink, L.; McNulty, B.; Gorzynski, J.; Goenka, S.; Ashley, E.A.; Jain, M.; Miga, K.H.; et al. Local Read Haplotagging Enables Accurate Long-Read Small Variant Calling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafin, K.; Pesout, T.; Chang, P.-C.; Nattestad, M.; Kolesnikov, A.; Goel, S.; Baid, G.; Kolmogorov, M.; Eizenga, J.M.; Miga, K.H.; et al. Haplotype-Aware Variant Calling with PEPPER-Margin-DeepVariant Enables High Accuracy in Nanopore Long-Reads. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Marschall, T.; Pisanti, N.; van Iersel, L.; Stougie, L.; Klau, G.W.; Schönhuth, A. WhatsHap: Weighted Haplotype Assembly for Future-Generation Sequencing Reads. J. Comput. Biol. 2015, 22, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UCSC-Nanopore-Cgl/Margin 2025. Available online: https://github.com/UCSC-nanopore-cgl/margin (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Martin, M.; Ebert, P.; Marschall, T. Read-Based Phasing and Analysis of Phased Variants with WhatsHap. In Haplotyping: Methods and Protocols; Peters, B.A., Drmanac, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 127–138. ISBN 978-1-0716-2819-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks 2020. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:167217261 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todi, A.; Narula, N.; Sharma, M.; Gupta, U. ConvNext: A Contemporary Architecture for Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Innovative Sustainable Computational Technologies (CISCT), Dehradun, India, 8–9 September 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jégou, H. Training Data-Efficient Image Transformers & Distillation through Attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Online, 18–24 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan Sifat, M.S.; Rahat Hossain, K.M. DeepIndel: A ResNet-Based Method for Accurate Insertion and Deletion Detection from Long-Read Sequencing. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kao, W.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Bai, J.; Wu, C.; Geng, F. ResNet Combined with Attention Mechanism for Genomic Deletion Variant Prediction. Autom. Control Comput. Sci. 2024, 58, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zook, J.M.; Chapman, B.; Wang, J.; Mittelman, D.; Hofmann, O.; Hide, W.; Salit, M. Integrating Human Sequence Data Sets Provides a Resource of Benchmark SNP and indel Genotype Calls. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bollas, A.; Wang, Y.; Au, K.F. Nanopore Sequencing Technology, Bioinformatics and Applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1348–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, A.; Au, K.F. PacBio Sequencing and Its Applications. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guguchkin, E.; Kasianov, A.; Belenikin, M.; Zobkova, G.; Kosova, E.; Makeev, V.; Karpulevich, E. Enhancing SNV Identification in Whole-Genome Sequencing Data through the Incorporation of Known Genetic Variants into the Minimap2 Index. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 238, Correction in BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baid, G.; Nattestad, M.; Kolesnikov, A.; Goel, S.; Yang, H.; Chang, P.-C.; Carroll, A. An Extensive Sequence Dataset of Gold-Standard Samples for Benchmarking and Development. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illumina/Hap.Py 2025. Available online: https://github.com/Illumina/hap.py?ysclid=mih5iay0og918538349 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

| Metric | Baseline (Inception_V3) | Alternative (EfficientNet_B3) | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 94.8 (95% CI: 94.56–95.05) | ↑ 95.31 (95% CI: 95.2–95.42) | 0.0067 * | 1.88 |

| Precision | 95.63 (95% CI: 95.41–95.84) | ↑ 95.78 (95% CI: 95.69–95.88) | 0.2432 | 0.67 |

| Recall | 93.76 (95% CI: 93.44–94.08) | ↑ 94.78 (95% CI: 94.64–94.91) | 0.0003 * | 2.96 |

| Metric | Baseline (Inception_V3) | Alternative (EfficientNet_B3) | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | ||||

| F1 | 99.04 (95% CI: 99.01–99.08) | ↑ 99.14 (95% CI: 99.1–99.18) | 0.0107 * | 1.68 |

| Precision | 99.64 (95% CI: 99.57–99.71) | ↑ 99.72 (95% CI: 99.67–99.78) | 0.0471 * | 0.94 |

| Recall | 98.45 (95% CI: 98.36–98.55) | ↑ 98.56 (95% CI: 98.44–98.68) | 0.1708 | 0.69 |

| Indel | ||||

| F1 | 93.8 (95% CI: 93.2–94.4) | ↑ 94.03 (95% CI: 93.38–94.69) | 0.6301 | 0.27 |

| Precision | 98.83 (95% CI: 98.74–98.92) | ↑ 99.01 (95% CI: 98.94–99.07) | 0.0042 * | 1.61 |

| Recall | 89.26 (95% CI: 88.2–90.32) | ↑ 89.55 (95% CI: 88.36–90.73) | 0.7455 | 0.18 |

| Metric | Baseline (Inception_V3) | Alternative (EfficientNet_B3) | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | ||||

| F1 | 99.11 (95% CI: 99.07–99.14) | ↑ 99.18 (95% CI: 99.15–99.22) | 0.0075 * | 1.75 |

| Precision | 99.64 (95% CI: 99.57–99.71) | ↑ 99.72 (95% CI: 99.67–99.78) | 0.0372 * | 1.00 |

| Recall | 98.58 (95% CI: 98.5–98.66) | ↑ 98.65 (95% CI: 98.55–98.75) | 0.2423 | 0.57 |

| Indel | ||||

| F1 | 97.1 (95% CI: 96.82–97.38) | ↑ 97.29 (95% CI: 96.99–97.59) | 0.3877 | 0.46 |

| Precision | 99.01 (95% CI: 98.9–99.12) | ↑ 99.24 (95% CI: 99.17–99.3) | 0.0022 * | 1.86 |

| Recall | 95.27 (95% CI: 94.78–95.76) | ↑ 95.42 (95% CI: 94.85–95.98) | 0.7070 | 0.20 |

| Metric | Baseline (Inception_V3) | Alternative (EfficientNet_B3) |

|---|---|---|

| Acc@1 | 77.9 | 81.6 |

| Params | 23.9 M | 12.3 M |

| Training time | 2 h and 34 min × 10 CV runs | 1 h and 59 min × 10 CV runs |

| Sample | Gender | Ancestry | BAM File |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG001 | Female | Utah/ European Ancestry | HG001.novaseq.pcr-free.30x.dedup.grch38.bam |

| HG003 | Male | Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish Ancestry | HG003.novaseq.pcr-free.30x.dedup.grch38.bam |

| HG005 | Male | Chinese Ancestry | HG005.novaseq.pcr-free.30x.dedup.grch38.bam |

| Dataset | Sample | Chromosomes | Number of Variants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total |

0/0,

Homozygous Reference | 0/1, Heterozygous | 1/1, Homozygous Alternate | |||

| Training | HG001 | 10 | 355,674 | 153,737 | 123,611 | 78,326 |

| Validation | HG001 | 20 | 156,159 | 71,858 | 53,263 | 31,038 |

| Test 1 | HG003 | Other | 4,822,356 | 1,196,591 | 2,196,336 | 1,429,429 |

| Test 2 | HG005 | Other | 4,473,118 | 1,008,100 | 1,975,012 | 1,490,006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gurianova, A.; Pestruilova, A.; Beliaeva, A.; Kasianov, A.; Mikhailova, L.; Guguchkin, E.; Karpulevich, E. Rethinking DeepVariant: Efficient Neural Architectures for Intelligent Variant Calling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010513

Gurianova A, Pestruilova A, Beliaeva A, Kasianov A, Mikhailova L, Guguchkin E, Karpulevich E. Rethinking DeepVariant: Efficient Neural Architectures for Intelligent Variant Calling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010513

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurianova, Anastasiia, Anastasiia Pestruilova, Aleksandra Beliaeva, Artem Kasianov, Liudmila Mikhailova, Egor Guguchkin, and Evgeny Karpulevich. 2026. "Rethinking DeepVariant: Efficient Neural Architectures for Intelligent Variant Calling" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010513

APA StyleGurianova, A., Pestruilova, A., Beliaeva, A., Kasianov, A., Mikhailova, L., Guguchkin, E., & Karpulevich, E. (2026). Rethinking DeepVariant: Efficient Neural Architectures for Intelligent Variant Calling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010513